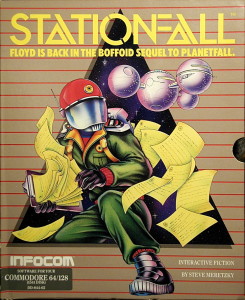

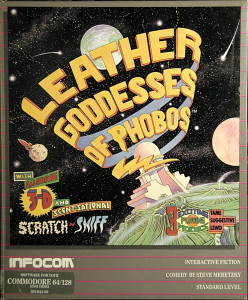

In an earlier article, I described Steve Meretzky during his peak years at Infocom as “second to no one on the planet in his ability to craft entertaining and fair puzzles, to weave them together into a seamless whole, and to describe it all concisely and understandably.” But his talents encompassed more than just good puzzle design. As an Infocom Imp, he had the unique gift of taking potentially hackneyed or just plain dumb premises and making them subtly, subversively smart. Who would have expected Leather Goddesses of Phobos, his ribald low-brow sex romp, to prove so clever and joyous and downright life-affirming? Who would have expected Stationfall, on its face the most rote sequel Infocom ever made — “Bring back Floyd!” had shouted the masses, and Meretzky had obliged — to turn gradually and without any warning whatsoever into the creepiest, most oppressive game in their canon?

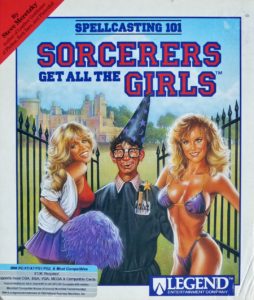

It’s because I know what he’s capable of at his best that I’ve always found Meretzky’s post-Infocom career a little disappointing. He did make good games after Infocom, but his track record from those years was far more mixed. During the 1990s, his dumb premises too often lacked the requisite touch of smarts to leaven the brew, and some of his design genius seemed to desert him. And sadly, his disappointments often smacked not of aiming too high, as he arguably had with his flawed would-be Infocom masterpiece A Mind Forever Voyaging, but rather from aiming too low, from being content to wallow in his established persona as a maker of wacky adventure games without adding that subversive spice that had elevated games like Leather Goddesses of Phobos and Stationfall to more interesting heights. Seen from this standpoint, his very first game after Infocom’s shuttering, Spellcasting 101: Sorcerers Get All the Girls, while a perfectly serviceable wacky adventure game in its own right, does rather portend the less inspiring phase of his career that was now beginning.

That said, when removed from the context of the games Meretzky was still to make, and particularly from that of the direct sequels to this game that were to follow, Spellcasting 101 is hardly a crime against adventure gaming. In fact, it was a wise if safe choice of a game to mark Legend Entertainment’s debut as a company and Meretzky’s as a freelance game designer. I already laid out the reasons for that in my last article: Steve Meretzky was well-known for his wacky comedy adventures; his Leather Goddesses of Phobos had been Infocom’s last big hit; Sex Sells in the abstract. Ergo Spellcasting 101. The first release of this very fragile new company was not the time to take too many artistic chances.

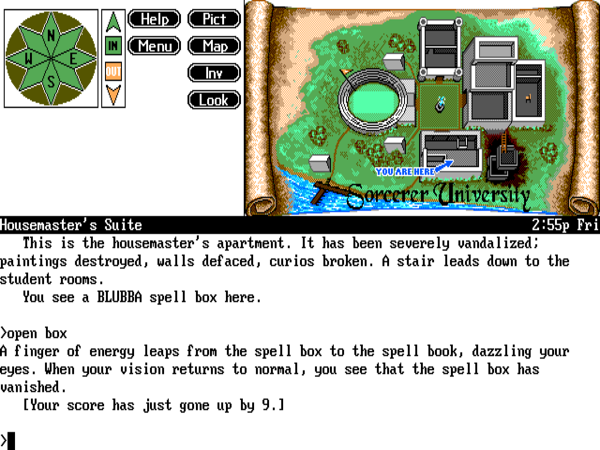

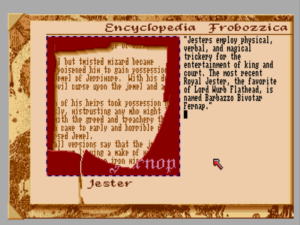

Spellcasting 101, then, finds Steve Meretzky sitting very comfortably in his wheelhouse, mixing unabashedly dumb humor — I might use the adjective “sophomoric,” but perhaps I should reserve that for the sequel Spellcasting 201 — with smart puzzles. You play Ernie Eaglebeak, the latest in adventure gaming’s long line of loser protagonists. He’s in love with a hot little number named Lola Tigerbelly, and dreams of going off to Sorcerer University to study magic, but, in a sex-reversed version of the Cinderella story, is prevented from doing either of these things (sorry!) by Joey Rottenwood, his evil stepfather. (With a name like that, I think old Joey should have been fronting a punk-rock band, but what do I know?) In the prologue, you in the role of Ernie defy your stepfather’s wishes in the matter of your education at least by sneaking off to Sorcerer University after your acceptance letter arrives in the mail.

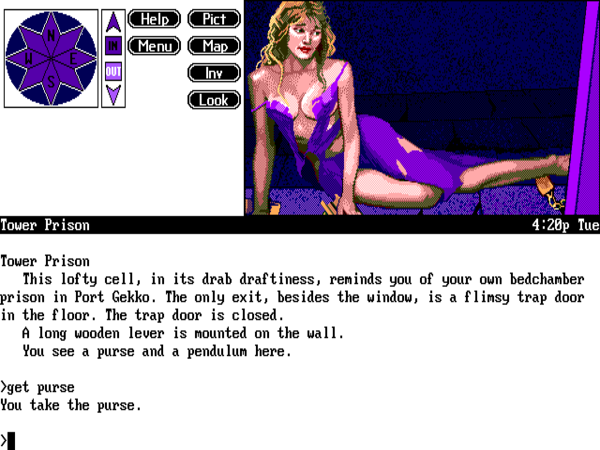

The game’s a little more risque than Leather Goddesses of Phobos, not least in that it now has pictures, but it’s still the sort of thing that only the most hormone-addled teenager is likely to find genuinely titillating; the sex is still very much played for laughs, not for, shall we say, self-gratification. Bob Bates of Legend had a rule of thumb for deciding what was and wasn’t acceptable to portray in the pictures. It’s best described as the “Playboy cover test”: anything that might appear on the cover — not the inside pages — of a Playboy magazine was okay. Like Leather Goddesses and its own two sequels, Spellcasting 101 does let you play in “nice” or “naughty” mode. Indeed, some of the most amusing gags in the games come if you choose to become one of the approximately one percent of players who don’t immediately switch to “naughty” mode. Suddenly nights of passion are replaced by, say, a night spent playing gin rummy. (Any resemblance to my marriage after eight and a half blissful years is, I’m sure, purely coincidental.)

One could wish that Meretzky had been able to let the player play as a female, as he had in Leather Goddesses of Phobos, but the need to depict so much of what happens visually, along with a more complicated plot and a more fleshed-out protagonist, precluded that possibility. The enforced male gaze does open the games up to a charge of sexism that it’s pointless to even try to refute. (Just look at those box covers and screenshots!) I suppose one could try to argue that the Spellcasting series is really making fun of the males doing all the leering, in the style of the Leisure Suit Larry series, but the humor doesn’t even have as much edge as those games, making it hard to regard it as satire. In the Spellcasting games’ defense, however, it’s all so over the top that it’s also hard for me at least to take any of it seriously enough to work up much outrage. Certainly Legend got little to no backlash from offended consumers, leaving Steve Meretzky’s wish to author a truly controversial game, which had burned since his stridently anti-Reagan effort A Mind Forever Voyaging back in 1985, still unrealized.

The explicit political statement that opened Leather Goddesses of Phobos felt bracing in its time, but the constant back-patting and referencing of notable contemporary culture warriors in the Spellcasting games gets to be a bit much. We get it, Steve, you’re a real rebel against the Establishment with your wacky adventure games.

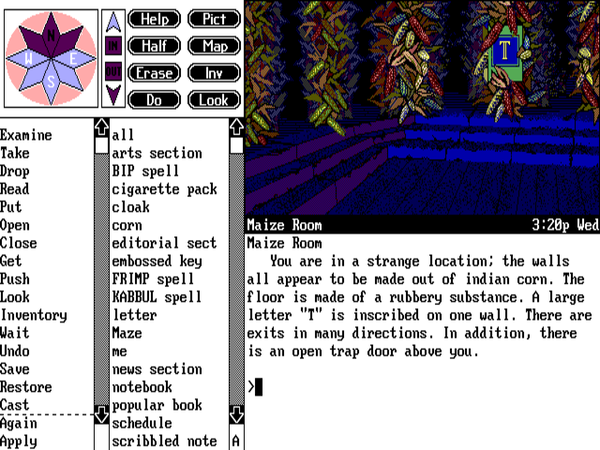

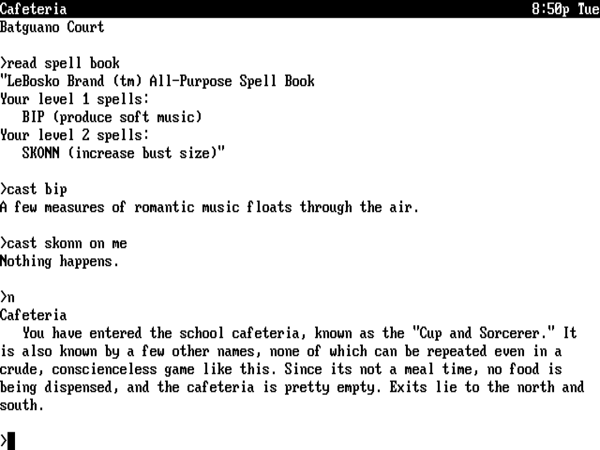

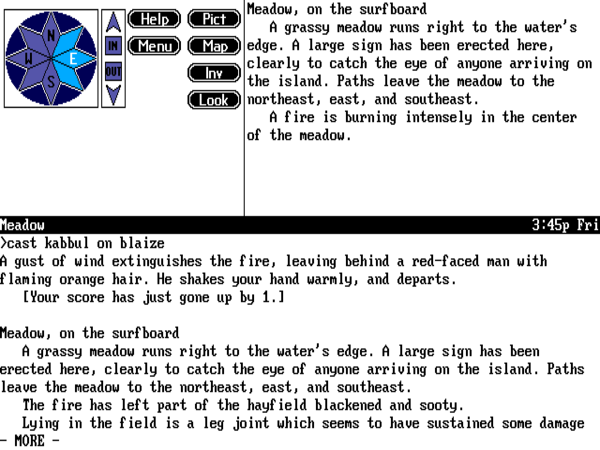

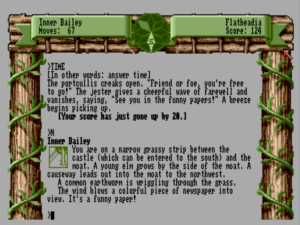

The humor in general is a little hit and miss. Where the first Spellcasting game in particular really shines, however, is the puzzle design — which, it must be said, is sometimes inseparable from the humor, and therein lies much of its brilliance. Many of the puzzles rely on wordplay, such as the unexpected use of a spell to “increase bust size.” In fact, there’s an entire extended sequence, “The Island of Lost Soles,” built around a premise that would have suited Nord and Bert Couldn’t Make Head or Tail of It perfectly. The inhabitants of the titular island have been entrapped within the various objects there. So, for example, “Blaize” is now trapped inside a campfire on the beach, and can be released only by casting a spell to “restore lost souls” on his true name. The usual problem with puzzles like this — and certainly the big problem with the should-have-been-a-classic Nord and Bert — is that they rely so much on the player’s native vocabulary and intuition. There are going to be some connections that even the most gifted player in both categories will simply never make, leaving her wandering hopelessly stuck. Spellcasting 101 solves that problem with a stroke of genius that’s disarmingly simple. Once you’ve wandered for a given amount of time without making further progress, a “hint fairy” will show up, saying something like “Have you seen Blaize around here?” With an actual name now to hand, you can search the island again, looking for the right object to which to apply it. Thereby does the game preserve the joy of making spontaneous intuitive connections without ever allowing you to get hopelessly hung up on those connections you can’t make. This, my friends, is what good design looks like.

Indeed, there’s a lot of attention paid in Spellcasting 101, as there would be in most of Legend’s later games to an even greater extent, to treating the player fairly. Even the combinatorial-explosion problem that made so frustrating Zork Zero, Meretzky’s final epic for Infocom, is addressed here by dividing the game into manageable chapters, each with its own discrete set of goals. Granted, some of the chapters are time-based, requiring you to plan your efforts around a constantly ticking clock. Solving these parts requires a fair amount of trial and error — i.e., figuring out what needs to be done over the course of several passes through a given chapter, then making a plan and bringing it all together via a final speed run. You will, in other words, be saving and restoring quite a lot despite the absence of more egregious design sins. Still, it should also be noted that Spellcasting 101‘s two sequels are much bigger sinners in this department. For long stretches of Spellcasting 101, the ticking clock disappears — something that most definitely can’t be said about the sequels.

So, this first Legend adventure game ever evinces a clear desire to be welcoming and accessible, if necessary at the expense of the sort of really intricate puzzles beloved by some of Infocom’s more hardcore disciples. Suffice to say that it’s a long, long way from the enormous, complicated, bafflingly non-linear Zork Zero. Kudos to Steve Meretzky, who was known to complain during Infocom’s latter days that their games were getting too easy, for recognizing the role his latest game needed to play in getting Legend off the ground, and for adjusting his design to suit the circumstances. Making due accommodation for the fact that this style of humor will never be to everyone’s taste, if there’s a holistic complaint to be leveled against the design it’s probably that the whole thing is just a little schizophrenic. What seems like it’s going to be a game about life at Sorcerer University suddenly transforms just as you’re settling into it into a series of vignettes, played on islands scattered all over the Fizzbuttle Ocean, that could have come from almost any adventure game. The Island of Lost Soles is a prime case in point: delightful as I find it on its own merits, it has nothing really to do with any other part of the game that houses it beyond yielding when all is said and done the requisite piece of the magical whatsit you’re trying to collect. The other island vignettes are less extended but equally isolated from one another and from the overarching plot of the game as a whole. Luckily, they’re all entertaining enough that the objection becomes more philosophical than impedimentary.

Call me overly sensitive if you must, but this scene from Spellcasting 201 is one of those that creeps me out just a bit. It also illustrates one of the inconsistencies in the series’s writing. Ernie Eaglebeak is the classic put-upon nerdy loser who couldn’t buy a date — until it’s time to score, whereupon all the sexy ladies suddenly have the hots for him.

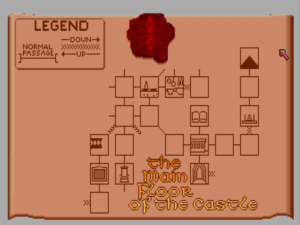

Spellcasting 201: The Sorcerer’s Appliance, Meretzky’s 1991 sequel, does fix this problem; the entire game now takes place inside the confines of a greatly expanded Sorcerer University. (The extended map is explained as the result of “an extensive campus renovation and expansion program.”) Now in his sophomore year, Ernie will need to save the world entirely from within the confines of the university and its immediate environs this time, in between attending classes and pledging to the fraternity Hu Delta Phart — whose name, along with those of its companion fraternities Tappa Kegga Bru, I Phelta Thi, and Gramma Eta Pi, gives a pretty good idea of the sort of humor you’ll find in these games, for anyone still in doubt.

Unfortunately, the previous game’s focus on playability and accessibility falls by the wayside. In Spellcasting 201, which is divided into chapters each representing one day, you’re the constant slave of a ticking clock that runs in increments of no less than five full minutes per turn. (Ernie, it appears, may be not just slothful but a genuine sloth.) While none of the puzzle solutions are out-of-left-field howlers, they do often require lots of trial and error. And thanks to that ticking clock, trial and error in this context means save and restore, again and again and again. As your collection of save files mounts, you also have to contend with a strict inventory limit that forces you to juggle objects in just the right way as you go about each day.

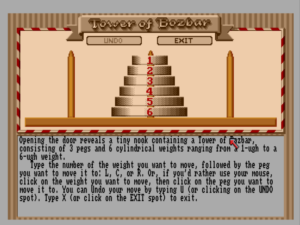

Some of the puzzles seem almost consciously engineered to be as annoying as possible, as if Meretzky has forgotten the lesson, long since taken to heart by his old peers at Infocom, that annoying the player in the name of comedy is seldom a good design strategy. Perhaps the worst offender of all is a magical musical instrument called a moodhorn, whose proper operation also serves as part of the game’s copy protection. You can play moodhorn compositions that are found in a music book that accompanies the game to affect the mood of the people around you — songs like “Happiness Interlude,” “Fear,” “Drippingtreesap’s Love Theme No. 15,” and “Winter Cold.” It sounds fun enough in theory, with, in the best tradition of the Enchanter series that did so much to inspire the Spellcasting games, lots of opportunities for Easter eggs even where puzzles solutions aren’t forthcoming. In practice, however, it’s just excruciating. Each song requires entering a series of six commands for manipulating the moodhorn, typing things like “vomp plunger,” “trib high glupp key,” and “oscilloop half burm lever” one after another in sequence. Because the moodhorn seems like it ought to be useful in many situations, you’ll likely spend much of the game wandering around trying out the twelve separate compositions listed in the music book, looking for the one place where the moodhorn actually is useful. Have I mentioned how excruciating this is? Just to add the final dollop of absurdity to the exercise, the ticking clock means that every moodhorn composition requires fully thirty precious minutes to play. (Even Yes albums don’t have songs that long!)

Legend stepped up to VGA graphics with Spellcasting 301, but the girls continue to look like they were assembled from mismatched spare parts left over after making other girls.

The series wobbled to its anticlimactic close with 1992’s Spellcasting 301: Spring Break, in which Ernie and his fraternity buddies head for the beach. The ticking clock remains and is as annoying as ever, although this time you are granted the mercy of being able to leave some tasks incomplete and still finish the game, albeit at a cost to your final score. Otherwise, the pleasures and pains are largely the same as those of the second game. The one immediately obvious difference is that the pictures, including all those babes that never seem to be put together quite the way real women are, are now in 256-color VGA rather than 16-color EGA. Given how much of a piece the Spellcasting games — particularly the last two — really are, I’d like to use the remainder of this article to try to understand what went so wrong with the series as a whole rather than to dwell on the details of Spellcasting 301‘s individual failings.

If we’re looking for someone to blame for the Spellcasting series’s problems — besides poor Steve Meretzky, that is — our first candidate has to be Ernie Eaglebeak, the hapless loser you’re forced to play in all three games. Simply put, he’s a horrid little twerp, the sort of kid that you want to drag down to the beach just so you can personally kick some sand in his face. Worse, he’s such a thoroughly uninteresting horrid little twerp. Even as odious adventure-game losers go, he’s no Leisure Suit Larry. And as Ernie Eaglebeak goes, so goes the rest of the cast of bimbos, dirty old men, and fraternity bro-dudes. The most sympathetic character in the series, a doddering old professor by the name of Otto Tickingclock, gets cuckolded and then accidentally killed by Ernie, who cares not a whit. There’s precious little warmth or joy to be found herein. It’s baffling to think that these games were written by the man who gave us Floyd, the first character in a text adventure that we ever really cared about. The death knell for any piece of fiction, interactive or otherwise, comes with the opposite reaction, when the reader says, “I really don’t care what happens to these people.” It’s hard to imagine anyone invested enough in Ernie Eaglebeak to give a darn about him.

As fiction, then, the Spellcasting series has its problems. Ditto as comedy. Various Implementors who worked at Infocom, as well as many commentators over the decades since, have described the strict limitations imposed by Infocom’s original 128 K Z-Machine as a counter-intuitive benefit to their games in that it forced authors to hone their works down to polished jewels, excising all of the weaker bits, retaining only the very strongest material. I’ve always been and to some extent remain a little skeptical of this thesis; as I’ve stated in previous articles, I think that some of the latter-day Infocom games in particular were trying to do a little too much in too small a space, and could have really used a few more kilobytes at their disposal. That said, the Spellcasting series makes a very strong counterargument for the value of restraint, stringently enforced if need be. With a system to hand for the first time that supported effectively unlimited amounts of text, Meretzky felt free to write… and write… and write. Some of the gags go on forever, to little if any comedic payoff. At Infocom, all this material would have been ruthlessly pared down by Meretzky’s fellow Imps and the testers, leaving only the genuinely funny bits behind. In this new order, however, it all just lies there on the screen, limp and lifeless as the comatose girl Ernie crawls into bed with in one of the series’s squickier episodes.

Cringe-worthy meta-textual comments like this one from Spellcasting 201 were par for the course in amateur AGT text adventures of the time, but they’re a little disconcerting to see in a $40 boxed commercial game. This sort of lazy writing would never have made it out of the first round of testing at Infocom.

Having broached the subject of Infocom’s working methods versus those Meretzky would utilize as an independent designer, I’d like to continue to follow that line of thought, for I think it might just lead us to the core reason that the Spellcasting series and so much of Meretzky’s other post-Infocom work pales in comparison to his earlier classics. Even after he became Infocom’s most famous Imp, Meretzky remained just one member of a creative collective which had the willingness and ultimately the authority to restrain his more questionable design impulses. This was the well-honed Infocom process for making great adventure games in action. I think that Meretzky needed that process — or at least a process involving lots of checks and balances — in order to turn out his best work. Legend did try as much as possible to duplicate the Infocom process for making games, even going so far as getting a number of former Infocom employees to help out as testers, but, being a much smaller, decentralized operation, was never able to duplicate the spirited to-and-fro on questions of writing and design that did so much for all of the Infocom Imps’ work. For Steve Meretzky, working hundreds of miles away and accorded a certain untouchable status as Legend’s star designer, the proof of the consequences is in the Spellcasting pudding. I’d like to quote from a recent discussion I had with Bob Bates, in which I asked him his own opinion of the ticking clock and the various other retrograde elements found in the Spellcasting games.

I was never really a fan of a ticking clock. For me personally, the fun of these games comes in the exploration. It comes often not in the solution to the puzzle, but in all the things you discover while you’re trying to solve the puzzle. As a designer, I try to entertain the player during that time, and to encourage the player to try offbeat stuff. Ninety percent of what a player does in an adventure game is wrong. You have to entertain them during that ninety percent in order for them to get the joy of the ten percent that’s actual puzzle-solving. So, I’m not a fan of the time-restricted thing in the same way that I’m not a fan of limiting what the player can carry, making him have to stop and think about swapping things in and out of his inventory. It doesn’t appeal to me as a player or a designer, but other people are different. With Steve, what you’re probably seeing is a designer choice rather than a company choice.

Bob Bates confirmed that Meretzky, as Legend’s star designer, was afforded lots of freedom to make exactly “the game he wanted to make” — freedom which was not afforded to any of the in-house teams who made Legend’s other games, who were expected to hew closely to the more progressive design philosophy Bob outlines above. There’s an important lesson here — important not just in the context of Meretzky’s career, or the history of the adventure game, or even in the context of game design in general. It’s rather an important lesson for all creators, and for those who would nurture them.

I would submit that allowing Meretzky to make exactly the games he wanted to make was in the end greatly to said games’ detriment. I say this not because Steve Meretzky was an egomaniac, was unusually headstrong, or was ever anything other than a very nice, funny, personable, honest fellow who positively oozed with creativity. I say it because Steve Meretzky was human, and creative humans need other humans to push back against them from time to time. I suspect that many of you could name an author or two who used to write taut, compelling books, until they got big enough that no one felt empowered to edit them anymore. Ditto for music; how many once-great bands have tarnished their image with lazy, filler-laden latter-day albums? Game designers are no different from other creative professionals in this respect. Meretzky needed someone to tell him, “Hey, Steve, this aspect of the game is more annoying than fun,” or “Hey, Steve, this huge text dump doesn’t really say much of anything interesting or funny,” or “Hey, Steve, can’t you do something to make this Ernie twerp a bit less odious?”

If the Spellcasting games on the one hand reflect the lack of a sufficiently rigorous design process, on the other they reflect a certain failure of ambition on the part of their creator. Steve Meretzky was a very practical guy at heart, and seems to have taken a strong lesson from the commercial disappointment that had been A Mind Forever Voyaging. He continued to dream grander dreams than the likes of Ernie Eaglebeak and Sorcerer University, but he never pushed hard enough to make his dreams into actualities. The legendary lost Meretzky game, which he broached so many times that it’s become a sort of in-joke among a whole swathe of industry old-timers, was an historical epic taking place on the Titanic‘s one and only voyage. Bob Bates admits that he didn’t want Meretzky to make this game for Legend. Since, as he put it, “everyone knows how that story ends,” he believed there was little commercial appeal to the idea, an opinion which is cast in a very questionable light by the massive success of the James Cameron movie on the same subject of a few years later. What might have been had Meretzky stuck to his guns and brazened out the chance to make this grander vision? It strikes me as unlikely that anyone today would be saying, “Gee, that Titanic game was okay, but I sure would have liked some more Ernie Eaglebeak instead.”

The irony of the Spellcasting series is that these dissipated games did as much to dissipate whatever commercial momentum the newly independent Meretzky had as surely as might have a more ambitious concept. Sales of the Spellcasting games dropped off markedly after the first sold more than 50,000 copies as Legend’s very first product. The dwindling sales doubtless constitute much of the reason that a planned fourth game, Spellcasting 401: The Graduation Ball, was never made. Few regretted its absence overmuch. Between the Spellcasting games and the downright embarrassing Leather Goddesses of Phobos 2, a half-assed graphic adventure he designed for the bankrupt Activision, Meretzky began his career as an independent game designer by ghettoizing himself as the “bad boy of adventure gaming” for years to come.

Ah, well… might-have-beens will always bloom eternal, won’t they? The first Spellcasting game at least can be a lot of fun, and perhaps comes off worse than is really fair here when I place it in the context of the increasingly dispiriting series as a whole. And I do want to note that I enjoy all of the other Legend text adventures much more than I do Spellcasting 201 and Spellcasting 301. I look forward to having more positive articles to write about them in the future.

(The Spellcasting games are available for purchase as a set on GOG.com.)