Most of history is guessing, and the rest is prejudice.

— Will Durant

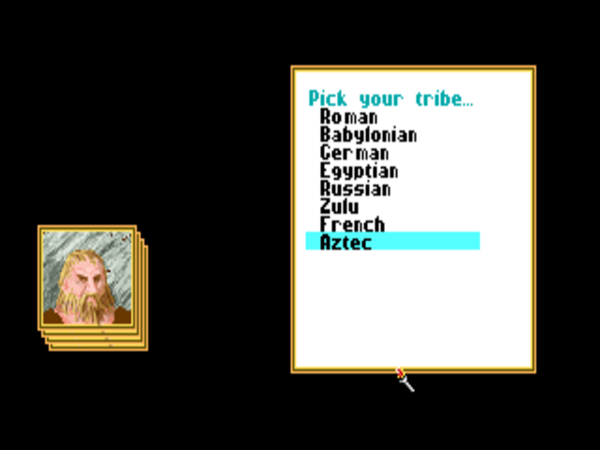

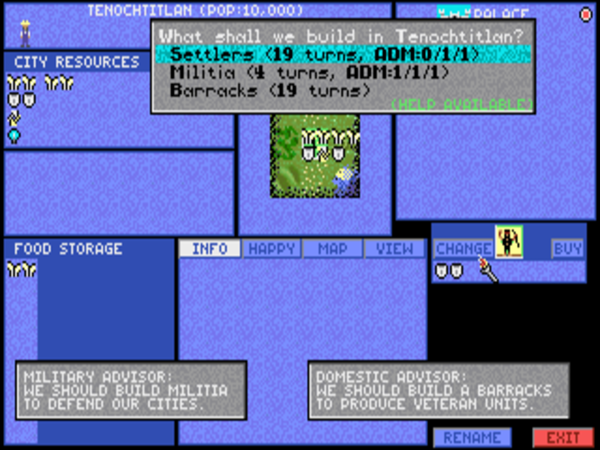

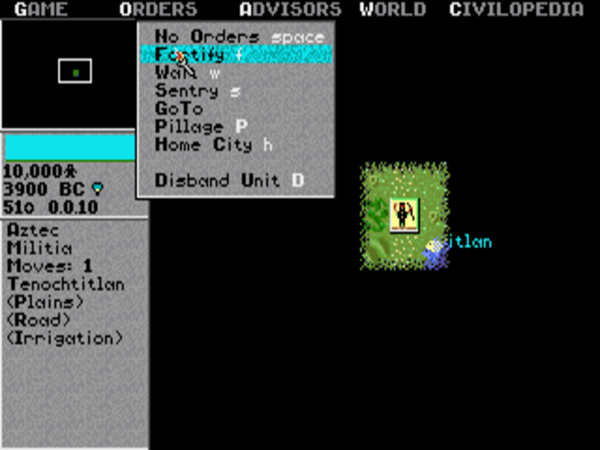

Every veteran Civilization player has had some unfortunate run-ins with the game’s “barbarians”: small groups of people who don’t belong to either your civilization or any of its major rivals, but nevertheless turn up to harass you from time to time with their primitive weaponry and decided aversion to diplomacy. More of a nuisance than a serious threat most of the time, they can spell the doom of your nascent civilization if they should march into your capital before you’ve set up a proper defense for it. What are we to make of these cultural Others — or, perhaps better said, culture-less Others — who don’t ever develop like a proper civilization ought to do?

The word “barbarian” stems from the ancient Greek “bárbaros,” meaning anyone who is not Greek. Yet the word resonates most strongly with the history of ancient Rome rather than Greece. The barbarians at the gates of the Roman Empire were all those peoples outside the emperor’s rule, who encroached closer and closer upon the capital over the course of the Empire’s long decline, until the fateful sacking of Rome by the Visigoths in AD 410. Given the months of development during which Civilization existed as essentially a wargame of the ancient world, it’s not hard to imagine how the word “barbarian” found a home there.

Civilization‘s barbarians, then, really are the game’s cultural Others, standing in for the vast majority of the human societies that have existed on our planet, who have never become “civilized” in the sense of giving up the nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle, taking up farming, and developing writing and the other traits of relatively advanced cultures. One of the biggest questions in the fields of history, archaeology, anthropology, and sociology has long been just why they’ve failed to do so. Or, to turn the question around: why have a minority of peoples chosen or been forced to become more or less civilized rather than remaining in a state of nature? What, in other words, starts a people off down the narrative of progress? I’d like to take a closer look at that question today, but first it would be helpful to address an important prerequisite: just what do we mean when we talk about a civilization anyway?

The word “civilization,” although derived from the Latin “civilis” — meaning pertaining to the “civis,” or citizen — is a surprisingly young one in English. Samuel Johnson considered it too new-fangled to be included in his Dictionary of the English Language of 1772; he preferred “civility” (a word guaranteed to prompt quite some confusion if you try to substitute it for “civilization” today). The twentieth-century popular historian Will Durant, perhaps the greatest and certainly the most readable holistic chronicler of our planet’s various civilizations, proposed the following definition at the beginning of his eleven-volume Story of Civilization:

Civilization is a social order promoting cultural creation. Four elements constitute it: economic provision, political organization, moral traditions, and the pursuit of knowledge and the arts. It begins where chaos and insecurity end. For when fear is overcome, curiosity and constructiveness are free, and man has passed by natural impulse towards the understanding and embellishment of life.

“Civilization” is a very loose word, whose boundaries can vary wildly with the telling and the teller. We can just as easily talk about human civilization in the abstract as we can a Western civilization or an American civilization. The game of Civilization certainly doesn’t make matters any more clear-cut. It first implies that it’s an holistic account of human civilization writ large, then proceeds to subsume up to seven active rival civilizations within that whole. In this series of articles, I’m afraid that I’m all over the place in much the same way; it’s hard not to be. But let’s step back now and look at how both abstract human civilization and the first individual civilizations began.

Homo sapiens — meaning genetically modern humans roughly our equals in raw cognitive ability — have existed for at least 200,000 years. Long before developing any form of civilization, they had spread to almost every corner of the planet. Human civilization, on the other hand, has existed no more than 12,000 years at the outside. Thus civilization spans only a tiny portion of human history, which itself spans a still vastly tinier portion of the history of life on our planet.

How and why did civilized societies finally begin to appear after so many centuries of non-civilized humanity? I’ll tackle the easier part of that question first: the “how”. Let me share with you a narrative of progress taking place in the traditional “cradle of civilization,” the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East, seat of the earliest known societies to have developed such hallmarks of mature civilization as writing.

For hundreds of thousands of years, the Fertile Crescent and the lands around it were made up of rich prairies, an ideal hunting ground for the nomadic peoples who lived there from the time of the proto-humans known as Homo erectus, 1.8 million years ago. But around 12,000 to 10,000 BC, the Middle East was transformed by the end of our planet’s most recent Ice Age, turning what had been prairie lands into steppes and desert. The peoples who lived there, who had once roamed and hunted so freely across the region, were forced to cluster in the great river valleys, the only places that still had enough water to sustain them. With wild game now much scarcer than it had been, they learned to raise crops and domesticated animals, which necessitated them staying in one place. Thus they made the transformation from nomadic hunting and gathering to sedentary farming — a transformation which marks the traditional dividing line between non-civilized and civilized peoples. “The first form of culture is agriculture,” writes Will Durant.

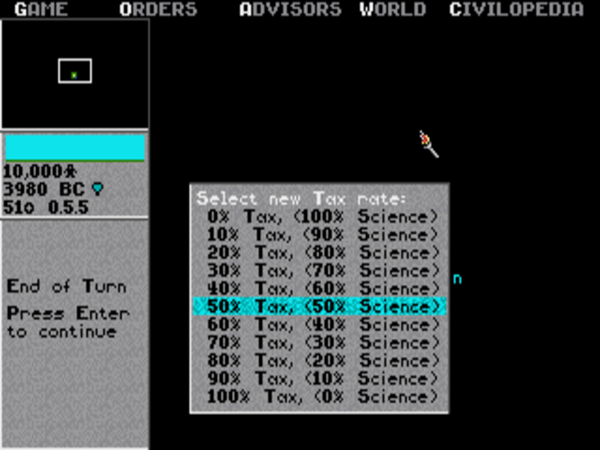

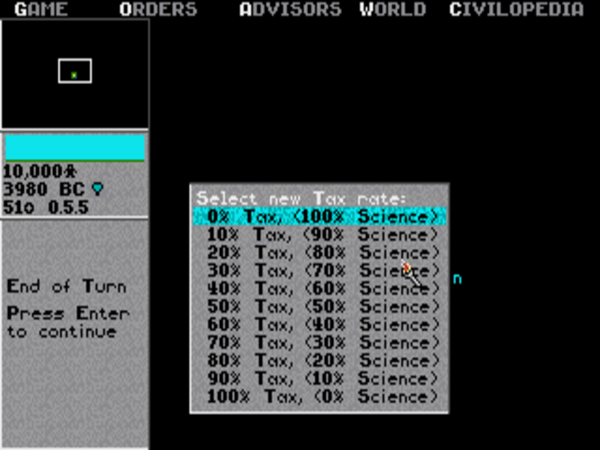

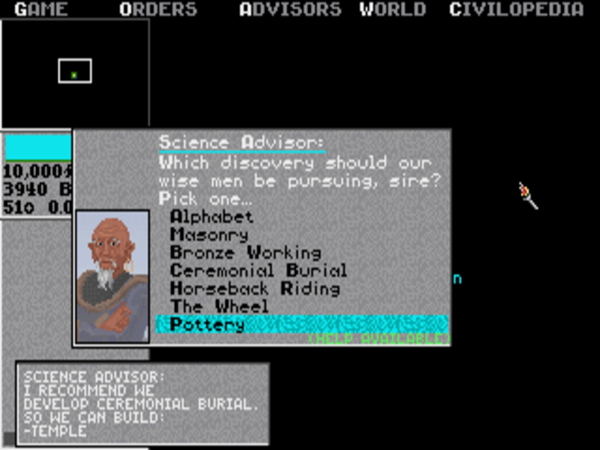

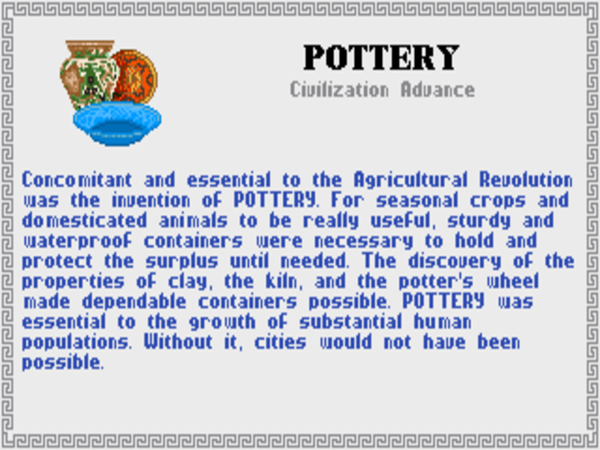

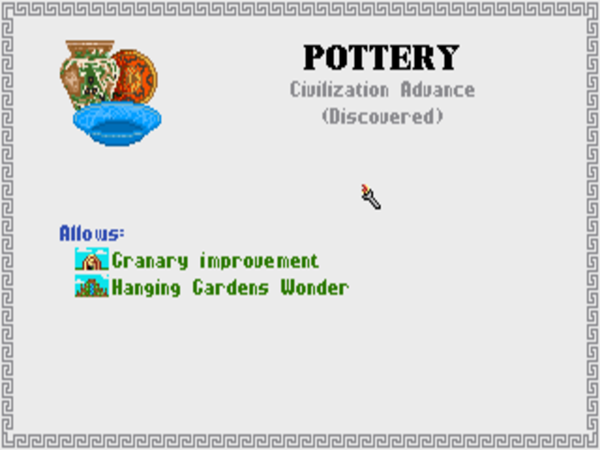

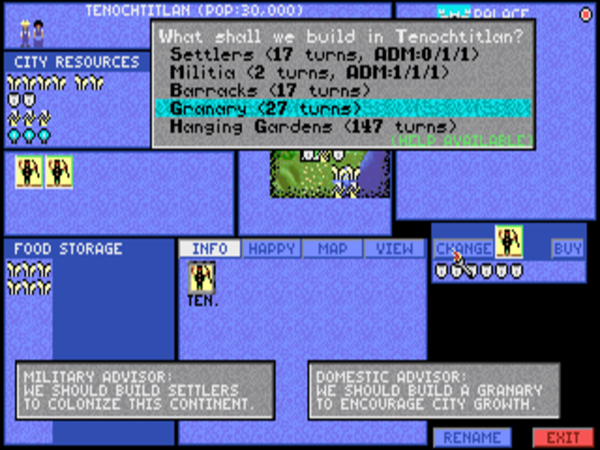

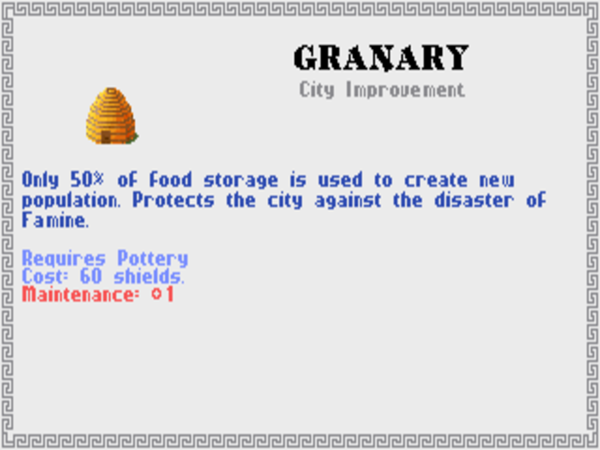

Early on, the peoples of the Fertile Crescent developed what is, perhaps counter-intuitively, the most fundamental technology of civilization: pottery, an advance whose value every Civilization player knows. As is described in the Civilopedia, the pots they made allowed them to “lay up provisions for the uncertain future” out of the crops they harvested, sufficient to get them through the winter months when other food sources were scarce.

One might say that the invention of pottery — or rather the onset of the future-oriented mindset it signifies — marks the point of fruition of humanity’s psychological transition from a state of nature to something akin to the modern condition. Some of you might be familiar with the so-called “worker placement” school of modern board games — a sub-genre on which the city-management screen in the original Civilization may have been a hidden influence. In a game like Agricola, you know that you need to collect enough food to feed your family by the end of the current round, and then again by the end of every subsequent round. You can rustle up a wild boar and slaughter it to deal with the problem now and let the future worry about itself, or you can defer other forms of gratification and use much more labor to plow a field and plant it with grains or vegetables, knowing that it will really begin to pay off only much later in the game. Deferred gratification is, as you’ve probably guessed, by far the better strategy.

It was, one might say, when humans developed the right mindset for playing a game like Agricola that everything changed. Something precious was gained, but something perhaps equally precious was lost. I use a lot of loaded language in this article, speaking about “primitive peoples” and “barbarians” as I do, and, good progressive that I am, generally write it under the assumption that civilization is a good thing. So, let me take a moment here to acknowledge that people do indeed lose something when they become civilized.

It is the fate of the civilized human alone among all the world’s creatures to have come unstuck in time. We’re constantly casting our gaze forward or backward, living all too seldom in the now. What the ancient Greeks called the physis moment — the complete immersion in life that we can observe in a cat on the prowl or a toddler on the playground — becomes harder and harder for us to recapture as we grow older. To think about the future also means to worry about it; to think about the past means to indulge in guilt and recrimination. “Of what are you thinking?” the polar explorer Robert Peary once asked one of his Inuit guides. “I do not have to think,” the Inuit replied. “I have plenty of meat.” An argument could be made that the barbarians are the wisest of all the peoples of the earth.

But, for better or for worse, we progressives don’t tend to make that argument. So, we return to our narrative of progress…

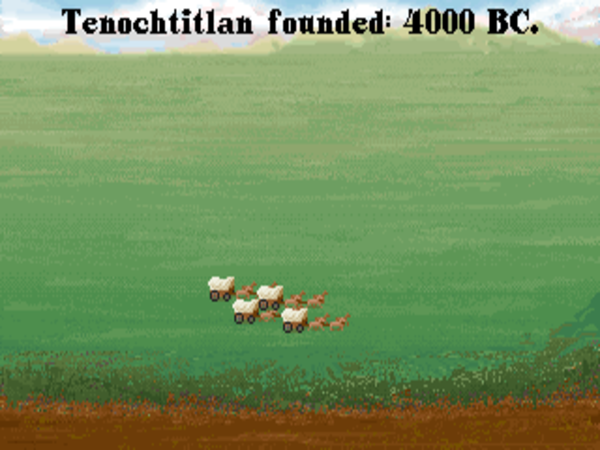

Cities and civilizations are inextricably bound together, not only historically but also linguistically; the word “city” is derived from the same Latin root as “civilization.” Cities provide a place for large numbers of people to meet and trade goods and ideas, and their economies of scale make specialization possible, creating space initially for blacksmiths and healers, later for philosophers and artists, as well as for hierarchies of class and power. They mark the point of transition from Karl Marx’s “primitive communism” to his so-called “slave society” — “Despotism” in the game of Civilization. On a more positive note, one might also say that the first cities with their early forms of specialization mark the first steps in Hegel’s long road toward a perfect, thymos-fulfilling end of history.

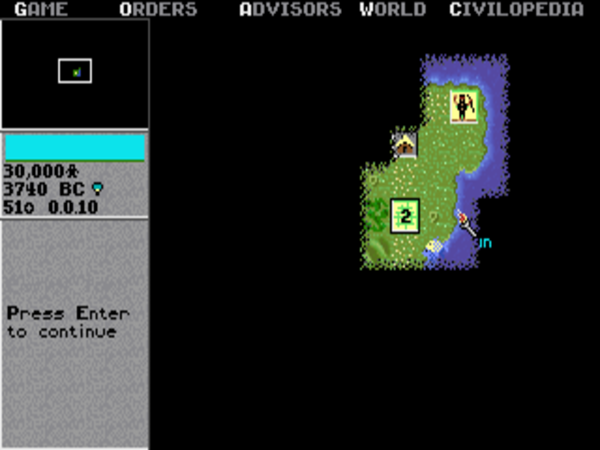

By the time a game of Civilization begins in 4000 BC, the Age of Stone was about to give way to the Age of Metal in the Fertile Crescent; people there were learning to smelt copper, which would soon be followed by bronze, as described by another pivotal early Civilization advance, Bronze Working. At this point, small cities had existed up and down the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years. The region was now rife with civilization, complete with religion, art, technology, written documents, and some form of government. Multi-roomed houses were built out of compressed mud or out of bricks covered with plaster, with floors made out of mud packed over a foundation of reeds. Inside the houses were ovens and stoves for cooking; just outside were cisterns for catching and storing rainwater. When not farming or building houses, the people carved statues and busts, and built altars to their gods. Around Jericho, one of if not the oldest of the settlements, they built walls out of huge stone blocks, thus creating the first example of a walled city in the history of the world. By 2500 BC, one of the civilizations of the Fertile Crescent would be capable of constructing the Pyramids of Giza, the oldest of Civilization‘s Wonders of the World and still the first thing most people think of when they hear that phrase.

But in writing about the Fertile Crescent I am of course outlining a narrative of progress for only one small part of the world. Elsewhere, the situation was very different, and would remain so for a long, long time to come. By way of illustrating those differences, let’s fast-forward about 4000 years on from the Pyramids, to AD 1500.

At that late date, much of the rest of the world had still not progressed as far as the Fertile Crescent of 2500 BC. The two greatest empires of the Americas, those of the Aztecs and the Incas, were for all intents and purposes still mired in the Stone Age, having not yet learned to make metals suitable for anything other than decoration. And those civilizations were actually strikingly advanced by comparison with many or most of the other peoples of the world. In Australia, on New Guinea and many other Pacific islands, over much of the rest of the Americas and sub-Saharan Africa, people trailed even the Aztecs and the Incas by thousands of years, having not yet learned the art of farming.

Consider that in 11,000 BC all peoples on the earth were still hunter-gatherers. Since then, some peoples had stagnated, while others — in the Middle East, in Europe, in parts of Asia — had advanced in ways that were literally unimaginable to their primitive counterparts. And so we arrive back at our original question: why should this be?

For a long time, Europeans, those heirs to what was first wrought in the Fertile Crescent, thought they knew exactly why. Their race was, they believed, simply superior to all of the others — superior in intelligence, in motivation, in creativity, in morality. And, as the superior race, the world and all its bounty were theirs by right. Thus the infernal practice of slavery, after having fallen into abeyance in the West since the Middle Ages, reared its head again in the new American colonies.

In time, some European attitudes toward the other peoples of the earth softened into a more benevolent if condescending paternalism. As the superior race, went the thinking, it was up to them to raise up the rest of the world, to Christianize it and to provide for it the trappings of civilization which it had been unable to develop for itself. Rudyard Kipling, that great poet of the latter days of the British Empire, urged his race to “take up the white man’s burden” as a moral obligation to the benighted inferior peoples of the world.

If there was any objective truth to the racial theories underlying Kipling’s rhetoric, we progressives would find ourselves on the horns of an ugly dilemma, split between our allegiance to rationality and science on the one hand and the visceral repugnance every fair-minded person must feel toward racism on the other. Fortunately for us, then, there is no dilemma here: racism is not only morally repugnant, it’s also bad science.

Any attempt to measure intelligence is a problematic exercise on the face of it; there are many forms of intelligence, such as empathy and artistic intelligence, about which the standard I.Q. test has nothing to say. And even within the limited scope of I.Q., cultural factors are notoriously difficult to remove from the testing process. Nevertheless, to the extent that we can measure such a thing there seems little or nothing to indicate that the overall cognitive ability of, say, a primitive tribesman from New Guinea suffers at all in comparison to that of a “civilized” person. Indeed, in some areas, such as spatial awareness and improvisational problem-solving, primitive people are quite likely our superiors. When we think about it, this stands to reason. For a tribesman on a jungle hunt, an error in judgment could mean that he and his family won’t have anything to eat that night — or, in the worst case, that he won’t get to return to his family ever again. Against that sort of motivator, the threat of failing to get into one’s favored university because of an SAT score that wasn’t all it might have been suddenly doesn’t feel quite so motivating.

All of which is good for our consciences, but it still doesn’t answer the question we’ve been dancing around since the beginning of this article. If racial differences don’t explain why the narrative of progress takes root in some peoples and not in others, what does? Plenty of other possibilities have been proposed, all centering more or less around geography and ecology.

Climate is one proposed determining factor, upon which the citizens of Germany, Scandinavia, the United States, and Canada among other places have sometimes leaned in order to explain why their countries’ economies are generally more dynamic than those of their southern counterparts. The fact that residents of more northerly regions had to work so much harder to survive — to find food and to stay warm in a much harsher climate — supposedly instilled in them a superior work ethic — and perhaps, necessity being the mother of invention, a greater intellectual flair to boot. Will Durant expressed a similar sentiment on a more universal scale in his Story of Civilization, claiming that the “heat of the tropics,” and the “lethargy” it breeds, are fundamentally hostile to civilization. But such claims too often find their evidence in ethnic stereotypes almost as execrable as those that spawned the notion of a white man’s burden, and of equally nonexistent veracity.

The fact is that the more dynamic economies of Northern Europe and the northernmost Americas are a phenomenon dating back only a few centuries at most, not the millennia that would make them solid evidence for the climate-as-destiny hypothesis; ancient Rome, the civilization that still springs to mind first when one says the word “civilization,” was itself situated in the warm, lazy, lethargic, fun-in-the-sun region of Europe. Indeed, the peoples of Northern Europe are comparative latecomers to the cultural party. Until not that many centuries ago, Northern Europe was quite literally the land of the barbarians; the Visigoths who so famously sacked Rome, it must be remembered, were a Germanic people. In the Americas as well, the most advanced native societies, the only ones to develop writing, were found in present-day Mexico and Peru rather than the United States or Canada.

The credence given to the climate-as-destiny theory for many years in the face of such obvious objections, combined with the way that evidence of civilization decays much faster in tropical environments than it does elsewhere, caused archaeologists to entirely overlook the existence of some tropical civilizations. A dry desert environment is, by contrast, about as perfect for preserving archaeological evidence as any natural environment can be, and this goes a long way in explaining why we know so much about certain regions of the world in comparison to others. Michael Heckenberger caused a sensation in archaeological and anthropological circles in 2009 when he published an article in Scientific American about the ancient Xingu people of the Amazon rain forest, who lived in well-developed, orderly communities which Heckenberger compared to the Victorian architect Ebenezer Howard’s utopian “garden cities of tomorrow.”

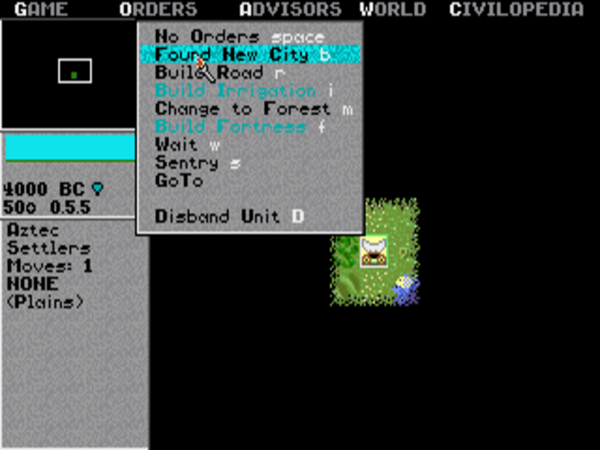

Another proposed determining factor for civilization or the lack thereof, also prevalent among scholars for many years, is even more oddly specific than the climate-as-destiny hypothesis. Civilization develops, goes the claim, when people find themselves forced to settle in river valleys of otherwise arid climates — i.e., exactly the conditions that prevailed in the Fertile Crescent. The only way for a growing population to survive in such a place was to develop the large-scale systems of irrigation that could bring the life-giving waters of the river further and further from their source. Undertaking such projects, the first ever examples of what we would call today public works, required a form of government, even of bureaucracy. Ergo, civilization.

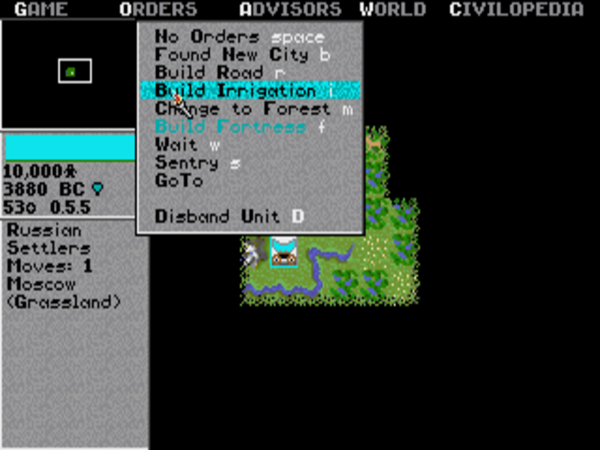

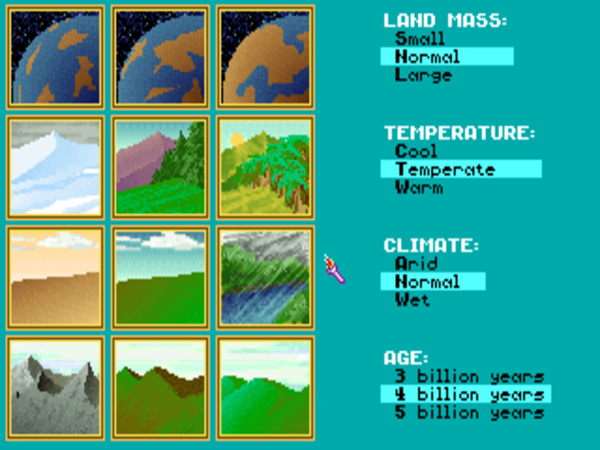

In addition to the example of the Fertile Crescent, proponents of the “hydraulic theory” of civilization have pointed to other examples of a similar process apparently occurring: in the Indus Valley of India, in the Yellow and Yangtze Valleys of China, in the river valleys of Mexico and Peru. The hydraulic theory was very much still a part of the anthropological discussion at the time that Sid Meier and Bruce Shelley were making Civilization, and likely informs the way that food-producing river squares are such ideal spots for founding your first cities, as well as the importance placed on irrigating the land around your cities in order to make them grow.

But more recent archaeology, in the Fertile Crescent and elsewhere, has cast doubt upon the hydraulic theory. It appears that the first governments developed not in tandem with systems of irrigation but rather considerably before them. The assertion that a fairly complex system of government is a prerequisite for large-scale irrigation remains as valid as ever, as does the game of Civilization‘s decision to emphasize the importance of irrigation in general. Yet it doesn’t appear that the need for irrigation was the impetus for government.

In 1997, a UCLA professor of geography and physiology named Jared Diamond published a book called Guns, Germs, and Steel, which, unusually, created an equal sensation in both the popular media and in academic circles. I described in my previous article the theory of technological determinism to which the game of Civilization seems to ascribe. In his book, Diamond asserted that, before there could be technological determinism, there must be a form of environmental determinism. One could of course argue that both the climate-as-destiny and the hydraulics-as-destiny theories I’ve just outlined fall into that category. What made Diamond’s work unique, however, was the much more holistic approach he took to the question of environmental determinism.

We tend to see the development of civilization through an anachronistic frame today, one which can distort reality as it was lived by the people of the time. In particular, we’ve taken to heart Thomas Hobbes’s famous description of the lives of primitive humans as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” just as we have the image of the development of agriculture, pottery, and all they wrought as the gateway to a better state of being. What we overlook is that nobody back in the day was trying to develop civilization; for people who have no experience with civilization, the very idea of it is, as I’ve already noted, literally unimaginable. No, people were just trying to get to the end of another day with food in their bellies.

We moderns overlook the fact that primitive farming was really, really hard, while hunting and gathering often wasn’t all that onerous at all when the environment was suited to it. Being a primitive farmer in most parts of the world meant working much longer hours than being a hunter-gatherer. Even today, the people of primitive agricultural societies are on average smaller and weaker than those of societies based on hunting and gathering, tending to die much younger after having lived much more unpleasant lives. The only way anyone would make the switch from hunting and gathering to agriculture was if there just wasn’t any other alternative. The first civilizations, in other words, arose not out of some visionary commitment to progress, but as a form of emergency crisis management.

With this wisdom in our back pocket, we can now revisit our narrative of progress about those first civilizations from a new perspective. Until roughly 12,000 years ago, it just didn’t make sense for people to be anything other than hunter-gatherers; the effort-to-reward ratio was all out of whack for farming. But then that began to change in some part of the world, thanks to a global change in climate. The end of the Ice Age in about 10,000 BC caused the extinction in some parts of the world of many of the large mammals on which humans had depended for meat, while the same climate change greatly benefited some forms of plant life, among them certain varieties of wild cereals that could, once clever humans figured out the magic of seeds and planting, become the bedrock of agriculture. By no means did all tribes in a given region adopt agriculture at the same time, but once any given tribe began to farm a positive-feedback loop ensued. An agricultural society makes much more efficient use of land — i.e., can support far more people per square mile — than does one based on hunting and gathering. Therefore the populations of nascent civilizations which adopted agriculture exploded in comparison to those neighbors who continued to try to make a go of it as hunter-gatherers despite the worsening conditions for doing so. In time, these neighboring Luddites were absorbed, exterminated, or driven out of the region by their more advanced neighbors — or they eventually learned from said neighbors and adopted agriculture themselves.

All of these things happened in some places that were adversely affected by the change in climate, beginning with the Fertile Crescent, but in other, equally affected places they did not. And in some of these places, the reasons why have long been troublingly unclear. For example, the African peoples living south of the Fertile Crescent suffered greatly from the shortage of wild game caused by the ending of the Ice Age, and had available to them the wild cereal known as sorghum, one of the most important early crops of their counterparts to the north. Yet these peoples, unlike said counterparts, failed to develop agriculture. Similarly, the peoples of Western Europe had flax available to them, while the peoples of the Balkans had einkorn wheat, both also staple crops of the Fertile Crescent. Yet these peoples as well failed to adopt agriculture until having it imposed upon them millennia later by encroachers from the south and east.

What made the Fertile Crescent and a select few other regions so special? It was this confusing mystery that prompted many an archaeologist to reach for ideas like the climate hypothesis and the hydraulic hypothesis.

But what Jared Diamond teaches us is that there’s very little mystery here at all when one looks at the situation in the right light. What made the Fertile Crescent so special was the fact that all of the plants I’ve just mentioned were available, just waiting to be domesticated. A civilization can’t live by sorghum, flax, or einkorn wheat alone; it requires the right combination of crops in order to sustain itself. Agriculture in the Fertile Crescent sprang up around eight staples that have become known as the “founder crops” of civilization: emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, barley, lentils, peas, chickpeas, bitter vetch, and flax. This combination alone provided enough nutrition to sustain a population, if need be, without any form of meat. No other region of the world was so richly blessed.

So, it was only in the Fertile Crescent that the people of approximately 10,000 BC had both a strong motivation to change their way of life from one based on hunting and gathering to one based on agriculture and the right resources at their disposal for actually doing so. In time, some peoples in some other parts of the world would encounter the same combination of motivation and opportunity, and civilizations would take root there as well. Many other peoples would remain happily committed to hunting and gathering, in some cases right up until the present day. One thing, however, would remain consistent: when civilizations which had developed agriculture encountered more primitive people and strongly wished to destroy them, absorb them, or just push them out, they would have little trouble doing so.

With this new way of looking at things, we understand that the reason so many of the first civilizations started in river valleys wasn’t due to the hydraulic hypothesis, or indeed to anything intrinsic to river valleys themselves. People rather moved into river valleys as their last remaining option when the environment outside them became uncongenial to their sustenance. And once they were there, circumstance forced them to become civilized. Thus the climate hypothesis of civilization is correct about one thing, even if it applies the lesson far too narrowly: civilization doesn’t arise in places of plenty; it arises in places where life is hard enough to force people to improvise.

But of course the development of civilization isn’t simply an either/or proposition. Even those civilizations which learned to farm and thus started down a narrative of progress didn’t progress at the same rate. Consider perhaps the most infamous example in history of a more advanced civilization meeting one that was less so: Hernán Cortés’s conquest of the Aztec Empire in the early 1500s with a tiny army that was vastly outnumbered by the native warriors it vanquished. The Aztecs had spotted about a 5000-year head start on the narrative of progress to the Spaniards, who could trace the roots of their civilization all the way back to those earliest settlers of the Fertile Crescent. Yet the timeline alone doesn’t suffice to explain why the Aztecs were so very much less advanced in so many ways. Jared Diamond asserts persuasively that, not only was the Aztec Empire not as advanced as Spain and other European nations in 1500, but it would never, ever have reached parity with the Europeans of 1500, not even if it had been given many more millennia to progress in splendid isolation. The reasons for this come down not to race, to climate, or to some sort of qualitative difference in river valleys, but to a natural environment that was very different in a more holistic sense.

Europeans had been blessed with thirteen different species of large mammals that were well-suited for domestication; these provided them with meat, milk, clothing, transportation, fertilizer, building materials, and, by pulling plows and turning grindstones, the industrial power of their day. In all of these ways, they spurred the progress of European civilization. Central America, by contrast, had no large mammals at all that were suitable for such roles. And in terms of plants as well, luck had favored the Europeans over the Aztecs; the latter lacked the wide assortment of nutrition-rich grains available to the former, having to make do instead with less nourishing corn as their staple crop. All of these factors meant that the Aztecs had to work much harder than the Europeans to feed and otherwise provide for their people. And so we come again to this idea of specialization, and the efficiencies it produces, as a key determinant of the narrative of progress. Will Durant noted that in a well-developed civilization “some men are set aside from the making of material things, and produce science and philosophy, literature and art.” The Aztecs could afford to set far fewer of their citizenry aside for such purposes than could the Europeans — a crippling disadvantage.

And there were still further disadvantages. The wider variety of animal life in Europe had led to the evolution of far more microbes hoping to infect it. European humans had in turn developed resistances to the cornucopia of germs they carried with them to the New World, resistances which the native inhabitants there lacked. And then the fact that Europe’s habitable regions were smaller and more densely populated had resulted in much more intense competition for land and resources, spurring the development of the technologies of warfare. Between Cortés’s guns, germs, and steel, the Aztecs never had a chance. The inexorable logic of environmental determinism ruled the day.

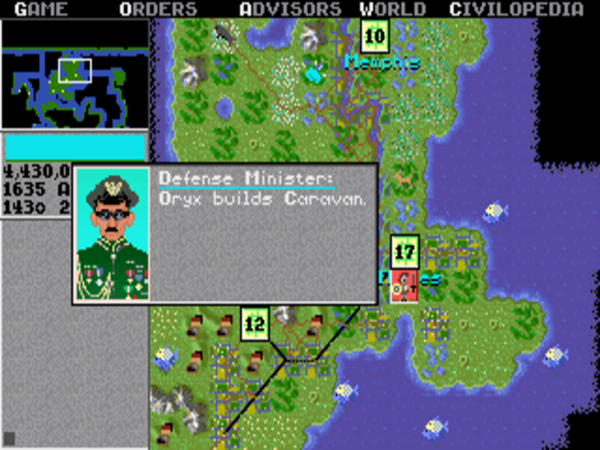

Civilization can hardly be expected to capture all of the nuances of Guns, Germs, and Steel, not least because it was made six years before Jared Diamond’s book was published. Yet to a surprising degree it gets the broad strokes of geography-as-destiny right. Barbarians, for instance, are spawned in the inhospitable polar regions of the world — regions in which agriculture, and thus civilization, is impossible. (Maybe all those barbarians who are constantly encroaching on your territory are really just trying to get warm…) In our real world as well, the polar regions have historically been populated only by primitive hunter-gatherer communities. Thankfully, Civilization has no interest in race as a determining factor in the narrative of progress. The game has occasionally been criticized for stereotyping its various civilizations in its artificial-intelligence algorithms, but one could equally argue that it’s really the individual civilizations’ chosen historical leaders — Abraham Lincoln, Josef Stalin, Napoleon, etc. — that are being modeled/stereotyped.

Jared Diamond’s theory of environmental determinism remains widely respected today if not universally accepted in its entirety. Some have objected to the very spirit of determinism that underlies it, which seems to assert that all of us humans really are strictly a product of our environment, which seems to imply that human history can be studied much as we do natural science, can be reduced to theorems and natural laws. This stands in stark contrast to an older view of history as driven by “great men,” as articulated by Thomas Carlyle: “Universal history, the history of what man has accomplished in this world, is at bottom the History of the Great Men who have worked here.” This approach to history, with its emphasis on the achievements and decisions of individual actors and its love for stirring narratives, has long since fallen out of fashion among academics like Diamond in favor of a more systemic approach. It’s certainly possible to argue that we’ve lost something thereby, that we’ve cut the soul out of the endeavor; we do suffer, it seems to me, a paucity of great tellers of history today. Whatever else you can say about it, Diamond’s approach to history doesn’t exactly yield a page-turner. Where is our time’s Will Durant?

Alexis de Tocqueville, that great French chronicler of early American democracy, mocked both politicians, who believe that all history occurs through their “pulling of strings,” and grand theorists like Jared Diamond, who believe all of history can be boiled down, science-like, to “great first causes.” He wrote instead of “tendencies” in history which nevertheless depend on the free actions of individuals to come to fruition. Maybe we too can settle for a compromise, and say that the conditions at least need to be right in order for our proverbial great persons to build great civilizations. Such a notion was articulated long before current academic fashion held sway by no less august a nation-builder than Otto von Bismark: “The statesman’s task,” he wrote, “is to hear God’s footsteps marching through history, and to try to catch on to His coattails as He marches past.” “It remains an open question,” allows even Jared Diamond, “how wide and lasting the effects of idiosyncratic individuals on history really are.”

For those of us who believe or wish to believe in the narrative of progress, meanwhile, Diamond’s ideas provide yet further ground for sobering thought, for they rather cut against the game of Civilization‘s spirit of progress as an historical inevitability. Consider once again that Homo sapiens roughly equal to ourselves in intelligence and capability have been around for 200,000 years, while human civilization has existed for only 12,000 years at the outside. The auspicious beginning to the game of Civilization, which portrays the entire natural history of your planet leading up to the moment in 4000 BC when you take control of your little band of settlers, rather makes it appear that these events were destined to happen. Yet the narrative of progress was anything but an inevitability in reality; its beginning was spurred only by a fluke change in climate. On the shifting sands of this random confluence of events have all of the glories of human civilization been built. Had the fluke not occurred, you and I would likely still be running through the jungle, spears in hand. (Would we be happier or sadder? An interesting question!) Or, had that fluke or some other spur to progress happened earlier, you and I might already be living on a planet orbiting Alpha Centauri.

(Sources: the books Civilization, or Rome on 640K a Day by Johnny L. Wilson and Alan Emrich, The Story of Civilization Volume I: Our Oriental Heritage by Will Durant, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies by Jared Diamond, The Face of the Ancient Orient: Near-Eastern Civilization in Pre-Classical Times by Sabatino Moscati, A Dictionary of the English Language by Samuel Johnson, The Spirit of the Laws by Montesquieu, Plough, Sword, and Book: The Structure of Human History by Ernest Gellner, Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study in Total Power by Karl Wittfogel, The Structures of Everyday Life: Civilization and Capitalism by Fernand Braudel, Souvenirs by Alexis de Tocqueville, and Nationalism: A Very Short Introduction by Steven Grosby; the article “Phantasms of Rome: Video Games and Cultural Identity” by Emily Joy Bembeneck, found in the book Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History; Scientific American of October 2009.)