Although they didn’t know one another at the time, Dave Grossman and Tim Schafer both found themselves at a similar place in life in the summer of 1989: just out of university and uncertain what to do next. Both saw the same unusual advertisement in the newspaper: an advertisement for programmers who could also write. Both applied, both were shocked when they were called out to George Lucas’s beautiful Skywalker Ranch for an interview, and both were fortunate enough to be hired to work for a division of Lucas’s empire that was still known at the time as Lucasfilm Games rather than LucasArts. It was quite a stroke of luck for two innately funny and creative souls who had never before seriously considered applying their talents to game development. “If I hadn’t seen that job listing,” says Schafer, “I would have ended up a database engineer, I think.” Similar in age and background as they were, Grossman and Schafer would remain all but inseparable for the next four years.

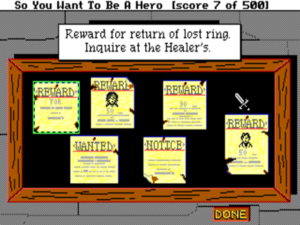

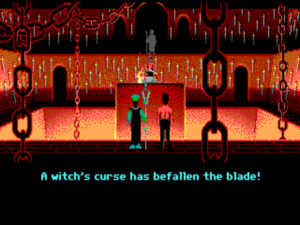

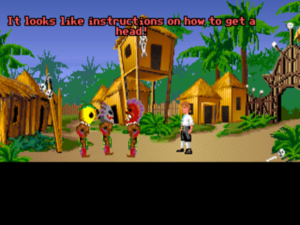

They spent the first weeks of that time working intermittently as play testers while they also attended what their new colleagues had dubbed “SCUMM University,” a combination technical boot camp and creative proving ground for potential adventure-game designers. Schafer:

A group of us were thrown into SCUMM University, because all of the LucasArts games used SCUMM [Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion]. The four of us were messing around with it, writing our own dialogue. They gave us some old art to work with, so we were just writing goofy stuff and joking around, trying to make each other laugh. I think LucasArts was watching us the whole time, and they picked me and [Grossman] out and said that they liked the writing.

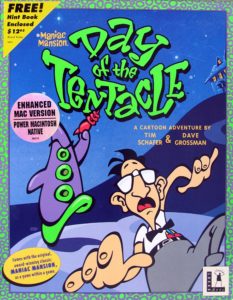

Grossman and Schafer were assigned to work as understudies to Ron Gilbert on the first two Monkey Island games. Here they got to hone their writing and puzzle-making chops, even as they absorbed the LucasArts philosophy of saner, fairer adventure-game design from the man most responsible for codifying and promoting it. In early 1992, shortly after the completion of Monkey Island 2, Gilbert announced that he was quitting LucasArts to start a company of his own specializing in children’s software. He left behind as a parting gift an outline of what would have been his next project had he stayed: the long-awaited, much-asked-for sequel to his very first adventure game, 1987’s Maniac Mansion. The understudies now got to step into the role of the stars; Maniac Mansion: Day of the Tentacle became Grossman and Schafer’s baby.

Times were changing quickly inside LucasArts, keeping pace with changes in the industry around them. After first conceiving of Day of the Tentacle as a floppy-disk-based game without voice acting, LucasArts’s management decided midway through its development that it should be a real technological showpiece in all respects — the first adventure game to be released simultaneously on floppy disk and CD-ROM. Along with X-Wing, the first actual Star Wars game LucasArts had ever been allowed to make, it would be one of their two really big, high-profile releases for 1993.

It was a lot of responsibility to heap on two young pairs of shoulders, but the end result demonstrates that Grossman and Schafer had learned their craft well as understudies. Day of the Tentacle is a spectacularly good adventure game; if not the undisputed cream of the LucasArts crop, it’s certainly in the conversation for the crown of their best single game ever. It achieves what it sets out to do so thoroughly that it can be very difficult for a diligent critic like yours truly to identify any weaknesses at all that don’t sound like the pettiest of nitpicking. The graphics are as good as any ever created under the limitations of VGA; the voice acting is simply superb; the puzzle design is airtight; the writing is sharp and genuinely, consistently laugh-out-loud funny; and the whole thing is polished to a meticulous sheen seldom seen in the games of today, much less those of 1993. It’s a piece of work which makes it hard for a critic to avoid gushing like a moon-eyed fanboy, as Evan Dickens of Adventure Gamers did when that site declared it to be the best game of its genre ever made:

The 1993 CD “talkie” version of Day of the Tentacle is a perfectly flawless adventure, the rarest of rare games, that which did nothing wrong. Nothing. There is no weakness in this game, no sieve. Stop waiting for the “but” because it won’t come. This is the perfect adventure game, the one adventure that brought every aspect of great adventures together and created such an enjoyable masterpiece, it almost seems to transcend the level of computer games.

Of course, there’s no accounting for taste. If you loathe cartoons, perhaps you might not like this game. If you prefer more serious plots or more rigorously cerebral puzzles, perhaps you won’t love it. Still, it’s hard for me to imagine very many people not being charmed by its gloriously cracked introductory movie and wanting to play further.

One of the few negative things I can say about Day of the Tentacle is that it’s more fun than it is truly innovative; it doesn’t break any new formal or thematic ground, being content to work entirely within a template which LucasArts and others had long since established by the point of its release. It remains at the end of the day a slapstick cartoon comedy, always the lowest-hanging fruit for an adventure-game design. Within that template, though, it executes everything so well that it’s almost annoying. This is the cartoon-comedy graphic adventure perfected, serving as the ultimate proof that much of what is sometimes forgiven or dismissed as “just the way adventure games are” is really the product of poor adventure-game design. Most of the problems that so many players consider to be intractable ones for the genre simply don’t exist here. The puzzles are goofy but always soluble, the dreaded sudden deaths and dead ends are nonexistent, and pixel hunts aren’t a problem amidst the game’s bright, clearly delineated scenes.

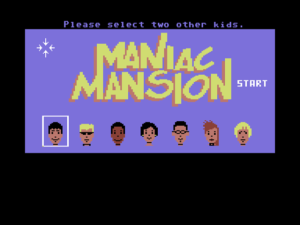

Day of the Tentacle‘s predecessor Maniac Mansion stood out from other adventure games in 1987, as it still does today, for allowing the player to select her own “party” of three characters, each with his or her own special skills, from a total of seven possibilities. The result was an unusual amount of replayability for the adventure-game genre; every possible combination of characters was capable of solving the game, but each would have to do so in a different way. Although this made Maniac Mansion a much more interesting game than it might otherwise have been, it was all nightmarishly complex for the game’s designer Ron Gilbert to map out. He would later state that only sheer naivete could ever have prompted him to expose himself to such pain — and, indeed, his first statement after finishing the game was, “I’m never doing anything like that again!” He held to that resolution throughout the rest of his time at LucasArts; his 1990 game The Secret of Monkey Island was at least as good as Maniac Mansion, but it owed its goodness to its writing, humor, art direction, and puzzle design, not to a similar formal ambition.

Against Gilbert’s advice, Grossman and Schafer first envisioned Day of the Tentacle operating along the same lines as Maniac Mansion, with another group of a half-dozen or so kids from which to choose a team. But the escalating cost of art and sound in the multimedia age played as big a role in nixing those plans as did the additional design complications; the two soon settled for giving the player control of a fixed group of three characters — which, they didn’t hesitate to point out, was still two more than most adventure games.

As this anecdote illustrates, Day of the Tentacle was never overly concerned with aping the details of its predecessor. Certainly if you play it without having played Maniac Mansion before, you’ll hardly be lost. Grossman:

We really couldn’t imitate the style of the original in the way you normally would with a sequel. Too much time had passed and the state of the art was radically different. We stopped thinking of it as a sequel almost immediately and just did our own thing, slathering our own personalities on top of that of Maniac Mansion.

Grossman and Schafer did reuse those elements of the earlier game that amused them most: the mad scientist Doctor Fred and his equally insane wife and son; the rambling old mansion where they all live; a memorable gag involving a hamster and a microwave; a pair of wise-cracking sentient tentacles, one of whom became the centerpiece of their plot and provided their sequel with its name. But of the kids the player got to control in Maniac Mansion, only Bernard, the über-nerd of the bunch, shows up again here. (Not coincidentally, Bernard had always been the favorite of the original game’s players, perhaps because of his range of unusual technical skills, perhaps because — if we’re being totally honest here — he was the teenage archetype who most resembled the typical young player.) Notably, Dave, the oddly bland default protagonist of the earlier game — he’s the only one you have to take with you, even though he’s the dullest of the lot — doesn’t show up at all here. In the place of Dave and the other kids, Grossman and Schafer augmented Bernard with two new creations of their own: a bro-dude “MegaBreth” roadie named Hoagie and a terminally nervous medical student named Laverne.

The story here does follow up on that of Maniac Mansion, but, once again, it doesn’t really matter whether you realize it or not. Five years after his previous adventure, Bernard receives a plea for help from Green Tentacle, informing him that Purple Tentacle has drunk some toxic sludge, which has instilled in him superhuman (supertentacle?) intelligence and a burning desire to enslave the world. Now, Doctor Fred has decided to deal with the problem by killing both tentacles; this is an obviously problematic plan from Green Tentacle’s perspective. Bernard convinces his two reluctant pals Hoagie and Laverne to head out to Doctor Fred’s mansion and stage an intervention. In attempting to do so, they unwittingly help Purple Tentacle to escape, and he sets out to take over the world. And so, just like that, we’re off to save the world.

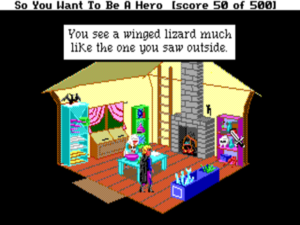

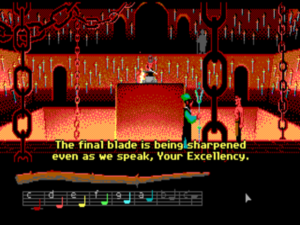

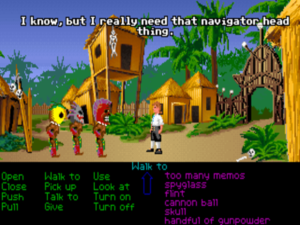

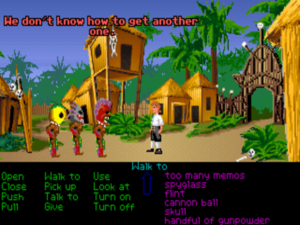

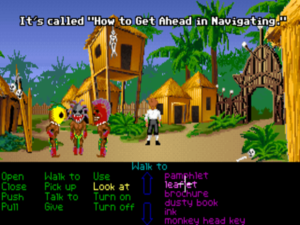

It doesn’t take Day of the Tentacle long to introduce its secret puzzling weapon: time travel. Doctor Fred, you see, just happens to have some time machines handy; known as “Chron-O-Johns,” they’re made from outdoor port-a-potties. With his plan for summary tentacle execution having failed, he hatches an alternative plan: to send the kids one day back in time, where they’ll prevent Purple Tentacle from ever drinking the toxic waste in the first place. But the time machines turn out to work about as well as most of Doctor Fred’s inventions. One sends Hoagie back 200 years instead of one day into the past, where he finds Ben Franklin and other Founding Fathers in the midst of writing the American Constitution in what will someday become Doctor Fred’s mansion; another sends Laverne 200 years into the future, when Purple Tentacle has in fact taken over the world and the mansion is serving as the dictatorial palace for him, his tentacle minions, and their human slaves; and the last time machine leaves Bernard right where (when?) he started.

You can switch between the kids at any time, and many of the more elaborate puzzles require you to make changes in one time to pave the way for solving them in another. In some instances, the kids can “flush” objects through time to one another using the Chron-O-John. On other occasions, a kid must find a way to hide objects inside the mansion, to be collected by another kid two or four centuries further down the time stream. “It was really fun to think about the effects of large amounts of time on things like wine bottles and sweaters in dryers,” remembers Grossman, “and to imagine how altering fundamentals of history like the Constitution and the flag could be used to accomplish petty, selfish goals like the acquisition of a vacuum and a tentacle costume.” Of course, just like in Maniac Mansion, it doesn’t pay to question how the kids are communicating their intentions to one another over such gulfs. Just go with it! This is, after all, a cartoon adventure.

Hoagie’s part of the plot coincidentally shares a setting and to some extent a tone with another clever and funny time-traveling adventure game that was released in 1993: Sierra’s Pepper’s Adventures in Time. Both games even feature a cartoon Ben Franklin in important roles. Yet it must be said that LucasArts’s effort is even sharper and funnier, its wit and gameplay polished to a fine sheen, with none of the wooliness that tends to cling even to Sierra’s best games. The inability to die or get yourself irrevocably stuck means that you’re free to just enjoy the ride — free, for instance, to choose the funniest line of dialog in any conversation without hesitation, safe in the knowledge that you’ll be able to do it over again if it all goes horribly wrong. “The player is never, ever punished for doing something funny,” wrote Charles Ardai, the best writer ever to work for Computer Gaming World magazine, in his typically perceptive review of the game. “Doing funny things is the whole point of Day of the Tentacle.”

Although Grossman and Schafer were and are bright, funny guys, their game’s sparkle didn’t come from its designers’ innate brilliance alone. By 1993, LucasArts had claimed Infocom’s old place as makers of the most consistently excellent adventure games you could buy. And as with the Infocom of old, their games’ quality was largely down to a commitment to process, including a willingness to work through the hard, unfun aspects of game development which so many of their peers tended to neglect. Throughout the development of Day of the Tentacle, Grossman and Schafer hosted periodic “pizza orgies,” first for LucasArts’s in-house employees, later for people they quite literally nabbed off the street. They watched these people play their game — always a humbling and useful experience for any designer — and solicited as much feedback thereafter as their guinea pigs could be convinced to give. Which parts of the game were most fun? Which parts were less fun? Which puzzles felt too trivial? Which puzzles felt too hard? They asked their focus groups what they had tried to do that hadn’t worked, and made sure to code in responses to these actions. As Bob Bates, another superb adventure-game designer, put it to me recently, most of what the player tries to do in an adventure game is wrong in terms of advancing her toward victory. A game’s handling of these situations — the elses in the “if, then, else” model of game logic — can make or break it. It can spell the difference between a lively, “juicy” game that feels engaging and interesting and a stubbornly inscrutable blank wall — the sort of game that tells you things don’t work but never tells you why. And of course these else scenarios are a great place to embed subtle hints as to the correct course of action.

Indeed, Grossman and Schafer continually asked themselves the same question in the context of every single puzzle in the game: “How is the player supposed to figure this out?” Grossman:

That [question] has stuck with me as a hallmark of good versus bad adventure-game design. Lots of people design games that make the designer seem clever — or they’re doing it to make themselves feel clever. They’ve forgotten that they’re in the entertainment business. The player should be involved in this thing too. We always went to great lengths to make sure all the information was in there. At these “pizza orgies,” one of the things we were always looking for was, are people getting stuck? And why?

The use of three different characters in three completely different environments also helps the game to avoid that sensation every adventurer dreads: that of being absolutely stuck, unable to jog anything loose because of one stubborn roadblock of a puzzle. If a puzzle stumps you in Day of the Tentacle, there’s almost always another one to go work on instead while the old one is relegated to the brain’s background processing, as it were.

And yet, as in everything, there is a balance to strike here as well: gating in adventure design is an art in itself. Grossman:

We were very focused on making things non-linear, but what we weren’t thinking about was that it’s possible to take that too far. Then you get a paralysis of choice. There’s kind of a sweet spot in the middle between the player being lost because they have too much to do and the player feeling railroaded because you’re telling them what to do. People don’t like either of those extremes very much, but somewhere in the middle, it’s like, “I’ve got enough stuff to think about, and I’m accomplishing some things, and I’ve got some new challenges.” That’s the right spot.

Day of the Tentacle nails this particular sweet spot, as it does so many others. It could never have done so absent extensive testing and — just as importantly — an open-mindedness on the part of its designers about what the testers were saying. It’s due to a lack of these two things that the adventure games of LucasArts’s rivals tended to go off the rails more often than not.

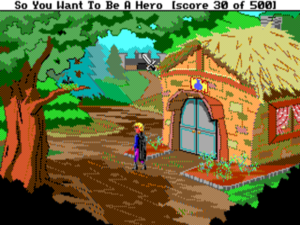

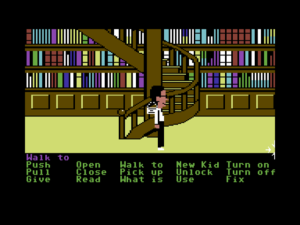

In addition to the superb puzzle design, Day of the Tentacle looks and sounds great — even today, even in its non-remastered version. The graphics are not only technically excellent but also evince an aesthetic sophistication rare in games of this era. The art department was greatly inspired by the classic Warner Bros. cartoons of Chuck Jones — Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Wile. E. Coyote and the Road Runner, etc. One day near the beginning of the project, the entire team made a field trip to sit at the feet of the 80-year-old Jones for a day and absorb some of his wisdom. Warner Bros. cartoons were always more visually skewed, more manic, and more deviously subversive than the straighter, more wholesome reels of Disney, and both the visuals and writing in Day of the Tentacle consciously mimic their style. Just as in the cartoons, there isn’t a straight line or right angle to be seen anywhere in the game. Everything, right down to the font in which text is printed, is bent, leaning, crooked, a fun-house world viewed through a fish-eye lens.

The art team, the unsung heroes of Day of the Tentacle. Standing from left to right are Lela Dowling, Sean Turner, Larry Ahern, and Peter Chan. Kneeling in front are Jesse Clark and Purple Tentacle. One additional artist, Kyle Balda, wasn’t present for this photograph.

Peter Chan, one of the artists on the team, notes that Grossman and Schafer “really trusted us and just let us go to town with what we believed would look best. If anybody on the art team had a good idea or suggestion, it was considered.” Here’s Schafer, speaking in an interview at the time of the game’s release, and obviously somewhat in awe himself at what LucasArts’s animators have come up with:

The kids have all kinds of grimaces and gestures and facial twists and contortions while they’re talking. They smile and their mouths open bigger than their heads and their tongues can hang out. They don’t just stand there. They blink, tap their feet, sigh, and even scratch their butts.

As soon as a character appears, you laugh, and that’s really important. You stare at the main characters for about thirty hours when you play the game, so they’d better be entertaining. With Bernard, as soon as you see him walking around for the first time, before he even says or does anything, you laugh. He walks goofy, he talks goofy, he’s even entertaining when he stands still. Walking Hoagie around is like piloting a blimp through a china shop, and Laverne is fun just to walk around because she seems to have a mind of her own — like she might do something dangerous at any moment.

The sound effects are drawn from the same well of classic animation. LucasArts actually bought many of them from a “major cartoon house,” resulting in all of the good old “boings” and “ka-pows” you might expect.

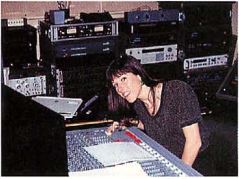

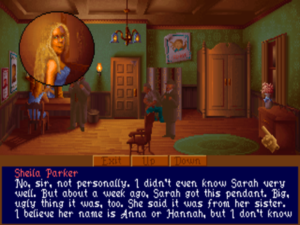

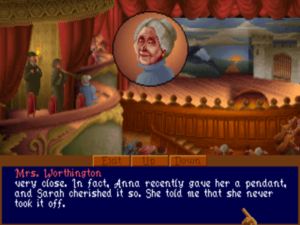

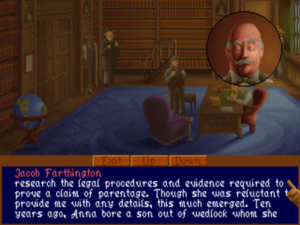

And the voice acting too is strikingly good. LucasArts was better equipped than almost any of the other game studios to adapt to the brave new world of CD-ROM audio, thanks to the connections which went along with being a subsidiary of a major film-production company. The actors’ dialog, totaling more than 4500 lines in all, was recorded at Hollywood’s Studio 222 under the supervision of a LucasArts associate producer named Tamlynn Barra. Although still in her twenties at the time, she had previously worked with many stage and video productions. She was thus experienced enough to recognize and find ways to counteract the most fundamental challenge of recording voice work for a computer game: the fact that the actors are expected to voice their lines alone in a production box, with no other actors to play off of and, too often, little notion of the real nature of the scene being voiced. “Getting the actors into character is very difficult,” she acknowledged. “Half the studio [time] is spent cueing up the actor for the scene.” And yet the fact that she knew she had to do this cueing was in a way half the battle. In contrast to many other computer-game productions — even those featuring a stellar cast of experienced actors, such as Interplay’s two contemporaneous Star Trek adventures — Day of the Tentacle has an auditory liveliness to it. It rarely feels as if the actor is merely reading lines off a page in a sound-proof booth, even if that’s exactly what she’s doing in reality.

Jane Jacobs, who voiced the Irish maid found inside the past-tense version of the mansion, performs before the microphone.

Unsurprisingly given LucasArts’s connections, the voice actors, while not household names, were seasoned professionals who arrived with their union cards in hand. The most recognizable among them was Richard Sanders, best known for playing the lovable but inept newscaster Les Nessman on the classic television sitcom WKRP in Cincinnati. During their initial discussions with Barra, Grossman and Schafer had actually suggested Les as the specific role model for Bernard, whereupon Barra made inquiries and found that Sanders was in fact available. He really was a perfect fit for Bernard; the character was “a bit of a stretch” for him, he said with a wink, because he was used to playing “more manly sorts of roles.”

Barra found the other voice talent using a process typical of television and radio productions but not so much of computer games: she sent sketches and descriptions of the characters out to Hollywood agents, who called their clients in to record audition tapes of their impressions. Then she and the rest of the development team chose their favorites. Many another game studio, by contrast, was recruiting its voice talent from its secretarial pool.

All of it led to an end result that feels today like it’s come unstuck from the time which spawned it. Certainly my own feeling upon firing up Day of the Tentacle for the first time in preparation for this article was that I had crossed some threshold into modernity after living in the ancient past for all of the years I’d previously been writing this blog. This impression is undoubtedly aided by the way that LucasArts steered clear of the approaches that generally date a game indelibly to the mid-1990s. Just to name the most obvious dubious trend they managed to resist: there are no digitized images of real actors shoehorned into this game via once cutting-edge, now aesthetically disastrous full-motion-video sequences.

Yet the impression of modernity encompasses more than the game’s audiovisual qualities; it really does encompass the sum total of the experience of playing it. The interface too just works the way a modern player would expect it to; no need to pick up a manual here to figure out how to play, even if you’ve never played an adventure game before. (The sole exception to this rule is the save system, which still requires you to know to press the F5 key in order to access it. On the other hand, keeping it hidden away does allow the game to avoid cluttering up its carefully honed aesthetic impression with a big old disk icon or the like.) Polish is a difficult quality to quantify, but I nevertheless feel fairly confident in calling Day of the Tentacle the most polished computer game made up to its release date of mid-1993. It looks and feels like a professional media production in every way.

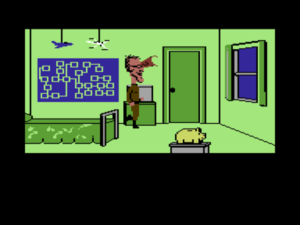

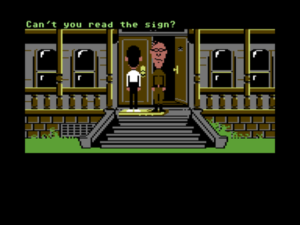

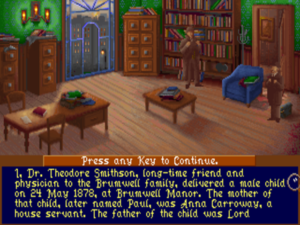

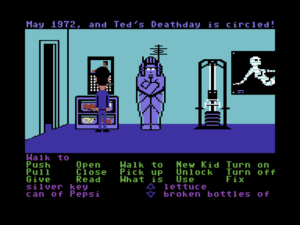

The most telling sign in Day of the Tentacle of how far computer gaming had come in a very short time is found on an in-game computer in the present-day mansion. There you’ll find a complete and fully functional version of the original Maniac Mansion in all its blocky, pixelated, bobble-headed glory. This game within a game was inspired by an off-hand comment which Grossman and Schafer had heard Ron Gilbert make during the Monkey Island 2 project: that the entirety of Maniac Mansion had been smaller than some of the individual animation sequences in this, LucasArts’s latest game. Placed in such direct proximity to its progeny, Maniac Mansion did indeed look “downright primitive,” wrote Charles Ardai in his review of Day of the Tentacle. “Only nostalgia or curiosity will permit today’s gamers to suffer through what was once state-of-the-art but is by today’s standards crude.” And yet it had only been six years…

Ardai concluded his review by writing that “it may not hold up for fifty years, like the cartoons that inspired it, but I expect that this game will keep entertaining people for quite some time to come.” And it’s here that I must beg to differ with his otherwise perceptive review. From the perspective of today, halfway already to the game’s 50th anniversary, Day of the Tentacle still holds up perfectly well as one of the finest examples ever of the subtle art of the adventure game. I see no reason why that should change in the next quarter-century and beyond.

(Sources: Computer Gaming World of July 1993 and September 1993; LucasArts’s newsletter The Adventurer of Fall 1992 and Spring 1993; Play of April 2005; Retro Gamer 22 and 81; Video Games and Computer Entertainment of July 1993. Online sources include Dev Game Club podcast 19; Celia Pearce’s conversation with Tim Schafer for Game Studies; 1Up‘s interview with Tim Schafer; The Dig Museum‘s interview with Dave Grossman; Adventure Gamers‘s interview with Dave Grossman.

A remastered version of Day of the Tentacle is available for purchase on GOG.com.)