In the spring of 1996, Brian Reynolds and Jeff Briggs took a long, hard look around them and decided that they’d rather be somewhere else.

At that time, the two men were working for MicroProse Software, for whom they had just completed Civilization II, with Reynolds in the role of primary designer and programmer and Briggs in that of co-designer, producer, and soundtrack composer. They had brought the project in for well under $1 million, all that their bosses were willing to shell out for what they considered to be a game with only limited commercial potential. And yet the early sales were very strong indeed, proof that the pent-up demand for a modestly modernized successor to Sid Meier’s masterstroke that Reynolds and Briggs had identified had been very, very real. Which is not to say that they were being given much credit for having proved their managers wrong.

MicroProse’s executives were really Spectrum Holobyte’s executives, ever since the latter company had acquired the former in December of 1993, in a deal lubricated by oodles of heedless venture capital and unsustainable levels of debt. Everything about the transaction seemed off-kilter; while MicroProse had a long and rich history and product portfolio, Spectrum Holobyte was known for the Falcon series of ultra-realistic combat flight simulators, for the first version of Tetris to run on Western personal computers, and for not a whole lot else. Seeing the writing on the wall, “Wild Bill” Stealey, the partner in crime with whom Sid Meier had founded MicroProse back in 1982, walked out the door soon after the shark swallowed the whale. The conjoined company went on to lose a staggering $57.8 million in two years, despite such well-received, well-remembered, and reasonably if not extraordinarily popular games as XCOM, Transport Tycoon, and Colonization. By the spring of 1996, the two-headed beast, which was still publishing games under both the Spectrum Holobyte and MicroProse banners, was teetering on the brink of insolvency, with, in the words of its CEO Stephen M. Race, a “negative tangible net worth.” It would require a last-minute injection of foreign investment capital that June to save it from being de-listed from the NASDAQ stock exchange.

The unexpectedly strong sales of Civilization II — the game would eventually sell 3 million copies, enough to make it MicroProse’s best seller ever by a factor of three — were a rare smudge of black in this sea of red ink. Yet Reynolds and Briggs had no confidence in their managers’ ability to build on their success. They thought it was high time to get off the sinking ship, time to get away from a company that was no longer much fun to work at. They wanted to start their own little studio, to make the games they wanted to make their way.

But that, of course, was easier said than done. They had a proven track record inside the industry, but neither Brian Reynolds nor Jeff Briggs was a household name, even among hardcore gamers. Most of the latter still believed that Civilization II was the work of Sid Meier — an easy mistake to make, given how prominently Meier’s name was emblazoned on the box. Reynolds and Briggs needed investors, plus a publisher who would be willing to take a chance on them. Thankfully, the solution to their dilemma was quite literally staring them in the face every time they looked at that Civilization II box: they asked Sid Meier to abandon ship with them. After agonizing for a while about the prospect of leaving the company he had co-founded in the formative days of the American games industry, Meier agreed, largely for the same reason that Reynolds and Briggs had made their proposal to him in the first place: it just wasn’t any fun to be here anymore.

So, a delicate process of disentanglement began. Keenly aware of the legal peril in which their plans placed them, the three partners did everything in their power to make their departure as amicable and non-dramatic as possible. For instance, they staggered their resignations so as not to present an overly united front: Briggs left in May of 1996, Reynolds in June, and Meier in July. Even after officially resigning, Meier agreed to continue at MicroProse for some months more as a part-time consultant, long enough to see through his computerized version of the ultra-popular Magic: The Gathering collectible-card game. He didn’t even complain when, in an ironic reversal of the usual practice of putting Sid Meier’s name on things that he didn’t actually design, his old bosses made it clear that they intended to scrub him from the credits of this game, which he had spent the better part of two years of his life working on. In return for all of this and for a firm promise to stay in his own lane once he was gone, he was allowed to take with him all of the code he had written during the past decade and a half at MicroProse. “They didn’t want to be making detailed strategy titles any more than we wanted to be making Top Gun flight simulators,” writes Meier in his memoir. On the face of it, this was a strange attitude for his former employer to have, given that Civilization II was selling so much better than any of its other games. But Brian Reynolds, Jeff Briggs, and Sid Meier were certainly not inclined to look the gift horse in the mouth.

They decided to call their new company Firaxis Games, a name that had its origin in a piece of music that Briggs had been tinkering with, which he had dubbed “Fiery Axis.” Jason Coleman, a MicroProse programmer who had coded on Civilization II, quit his job there as well and joined them. Sid Meier’s current girlfriend and future second wife Susan Brookins became their office manager.

The first office she was given to manage was a cramped space at the back of Absolute Quality, a game-testing service located in Hunt Valley, Maryland, just a stone’s throw away from MicroProse’s offices. Their landlords/flatmates were, if nothing else, a daily reminder of the need to test, test, test when making games. Brian Reynolds (who writes of himself here in the third person):

CEO Jeff Briggs worked the phones to rustle up some funding and did all the hard work of actually putting a new company together. Sid Meier and Brian Reynolds worked to scrape together some playable prototype code, and Jason Coleman wrote the first lines of JACKAL, the engine which these days pretty much holds everything together. Office-manager Susan Brookins found us some office furniture and bought crates of Coke, Sprite, and Dr. Pepper to stash in a mini-fridge Brian had saved from his college days. We remembered that at some indeterminate point in the past we were considered world-class game designers, but our day-to-day lives weren’t providing us with a lot of positive reinforcement on that point. So, for the first nine months of our existence as a company, we clunked over railroad tracks in the morning, played Spy Hunter in the upstairs kitchen, and declared “work at home” days when Absolute Quality had competitors in the office.

Once the necessary financing was secured, the little gang of five moved into a proper office of their own and hired more of their former colleagues, many of whom had been laid off in a round of brutal cost-cutting that had taken place at MicroProse the same summer as the departure of the core trio. These folks bootstrapped Firaxis’s programming and art departments. Thanks to the cachet of the Sid Meier name/brand, the studio was already being seen as a potential force to be reckoned with. Publishers flew out to them instead of the other way around to pitch their services. In the end, Firaxis elected to sign on with Electronic Arts, the biggest publisher of them all.

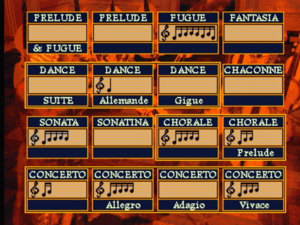

The three founding fathers had come into the venture with a tacit understanding about the division of labor. Brian Reynolds would helm a sprawlingly ambitious but fundamentally iterative 4X strategy game, a “spiritual successor” to Civilization I and II. This was the project that had gotten Electronic Arts’s juices flowing; its box would, it went without saying, feature Sid Meier’s name prominently, no matter how much or how little Meier ultimately had to do with it. Meanwhile Meier himself would have free rein to pursue the quirkier, more esoteric ideas that he had been indulging in ever since finishing Civilization I. And Briggs would be the utility player, making sure the business side ran smoothly, writing the music, and pitching in wherever help was needed on either partner’s project.

Sid Meier has a well-earned reputation for working rapidly and efficiently. It’s therefore no surprise that he was the first Firaxis designer to finish a game, and by a wide margin at that. Called simply Gettysburg! — or rather Sid Meier’s Gettysburg! — it was based upon the battle that took place in that Pennsylvania city during the American Civil War. More expansively, it was an attempt to make a wargame that would be appealing to grognards but accessible enough to attract newcomers, by virtue of being real-time rather than turn-based, of being audiovisually attractive, and of offering a whole raft of difficulty levels and tutorials to ease the player into the experience. Upon its release in October of 1997, Computer Gaming World magazine called it “a landmark, a real-time-strategy game whose unique treatment of its subject matter points to a [new] direction for the whole genre.” For my own part, being neither a dedicated grognard nor someone who shares the fascination of so many Americans for the Civil War, I will defer to the contemporary journal of record. I’m sure that Gettysburg! does what it does very well, as almost all Sid Meier games do. On the broader question of whether it brought new faces into the grognard fold, the verdict is more mixed. Meier writes today that “it was a success,” but it was definitely not a hit on the scale of SSI’s Panzer General, the last wargame to break out of its ghetto in a big way.

To the hungry eyes of Electronic Arts, Gettysburg! was just the appetizer anyway. The main dish would be Alpha Centauri.

The idea for Alpha Centauri had been batted around intermittently as a possible “sequel to Civilization” ever since Sid Meier had made one of the two possible victory conditions of that game the dispatching of a spaceship to that distant star, an achievement what was taken as a proof that the nation so doing had reached the absolute pinnacle of terrestrial achievement. In the wake of the original Civilization’s release and success, Meier had gone so far as to prototype some approaches to what happens after humanity becomes a star-faring species, only to abandon them for other things. Now, though, the old idea was newly appealing to the principals at Firaxis, for commercial as much as creative reasons. They had left the rights to the Civilization franchise behind them at MicroProse, meaning that a Firaxis Civilization III was, at least for the time being, not in the cards. But if they made a game called Alpha Centauri that used many of the same rules, systems, and gameplay philosophies, and that sported the name of Sid Meier on the box… well, people would get the message pretty clearly, wouldn’t they? This would be a sequel to Civilization in all but its lack of a Roman numeral.

When he actually started to try to make it happen, however, Brian Reynolds learned pretty quickly why Sid Meier had abandoned the idea. What seemed like a no-brainer in the abstract proved beset with complications when you really engaged. The central drama of Civilization was the competition and conflict between civilizations — which is also, not coincidentally, the central drama of human history itself. But where would the drama come from for a single group of enlightened emissaries from an earthly Utopia settling an alien planet? Whom would they compete against? Just exploring and settling and building weren’t enough, Reynolds thought. There needed to be a source of tension. There needed to be an Other.

So, Brian Reynolds started to read — not history this time, as he had when working on Civilization II, but science fiction. The eventual manual for Alpha Centauri would list seven authors that Reynolds found particularly inspiring, but it seems safe to say that his lodestar was Frank Herbert, the first writer on the list. This meant not only the inevitable Dune, but also — and perhaps even more importantly — a more obscure novel called The Jesus Incident that Herbert co-wrote with Bill Ransom. One of Herbert’s more polarizing creations, The Jesus Incident is an elliptical, intensely philosophical and even spiritual novel about the attempt of a group of humans to colonize a planet that begins to manifest a form of sentience of its own, and proves more than capable of expressing its displeasure at their presence on its surface. This same conceit would become the central plot hook of Alpha Centauri.

Yes, I just used the word “plot.” And make no mistake about its significance. Of the threads that have remained unbroken throughout Sid Meier’s long career in game design, one of the most prominent is this mild-mannered man’s deep-seated antipathy toward any sort of set-piece, pre-scripted storytelling in games. Such a thing is, he has always said, a betrayal of computer games’ defining attribute as a form of media, their interactivity. For it prevents the player from playing her way, having her own fun, writing her own personal story using the sandbox the designer has provided. Firaxis had never been intended as exclusively “Sid Meier’s company,” but it had been envisioned as a studio that would create, broadly speaking, his type of games. For Reynolds to suggest injecting strong narrative elements into the studio’s very first 4X title was akin to Deng Xiaoping suggesting to his politburo that what post-Cultural Revolution China could really use was a shot of capitalism.

And yet Meier and the others around Reynolds let him get away with it, just as those around Deng did. They did so because he had proven himself with Colonization and Civilization II, because they trusted him, and because Alpha Centauri was at the end of the day his project. They hadn’t gone to the trouble of founding Firaxis in order to second-guess one another.

Thus Reynolds found himself writing far more snippets of static text for his strategy game than he had ever expected to. He crafted a series of textual “interludes” — they’re described by that word in the game — in which the planet’s slowly dawning consciousness and its rising anger at the primates swarming over its once-pristine surface are depicted in ways that mere mechanics could not entirely capture. They appear when the player reaches certain milestones, being yet one more attempt in the annals of gaming history to negotiate the tricky terrain that lies between emergent and fixed narrative.

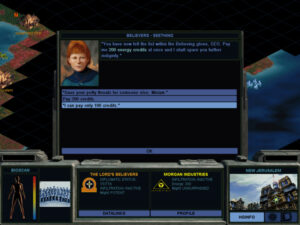

An early interlude, delivering some of the first hints that the planet on which you’ve landed may be more than it seems.

Walking alone through the corridors of Morgan Industries, you skim the security reports on recent attacks by the horrific native “mind worms.” Giant swarms, or “boils,” of these mottled 10cm nightmares have wriggled out of the fungal beds of late, and now threaten to overwhelm base perimeters in several sectors. Victims are paralyzed with psi-induced terror, and then experience an unimaginably excruciating death as the worms burrow into the brain to implant their ravenous larvae.

Only the most disciplined security squads can overcome their fear long enough to trigger the flame guns which can keep the worms at bay. Clearly you will have to tend carefully to the morale of the troops.

Furthermore, since terror and surprise increase human casualties dramatically in these encounters, it will be important to strike first when mind-worm boils are detected. You consider ordering some Former detachments to construct sensors near vulnerable bases to aid in such detection efforts.

Alpha Centauri became a darker game as it became more story-oriented, separating itself in the process from the sanguine tale of limitless human progress that is Civilization. Reynolds subverted Alpha Centauri’s original backstory about the perfect society that had finally advanced so far as to colonize the stars. In his new version, progress on Earth has not proved all it was cracked up to be. In fact, the planet his interstellar colonists left behind them was on its last legs, wracked by wars and environmental devastation. It’s strongly implied if not directly stated that earthly humanity is in all likelihood extinct by the time the colonists wake up from cryogenic sleep and look down upon the virgin new world that the game calls simply “Planet.”

Both the original Civilization and Alpha Centauri begin by paraphrasing the Book of Genesis, but the mood diverges quickly from there. The opening movie of Civilization is a self-satisfied paean to Progress…

…while that of Alpha Centauri is filled with disquieting images from a planet that may be discovering the limits of Progress.

Although the plot was destined to culminate in a reckoning with the consciousness of Planet itself, Brian Reynolds sensed that the game needed other, more grounded and immediate forms of conflict to give it urgency right from the beginning. He created these with another piece of backstory, one as contrived as could possibly be, but not ineffective in its context for all that. As told at length in a novella that Firaxis began publishing in installments on the game’s website more than six months before its release, mishaps and malevolence aboard the colony ship, which bore the sadly ironic name of Unity, led the colonists to split into seven feuding factions, each of whom inflexibly adhere to their own ideology about the best way to organize human society. The factions each made their way down to the surface of Planet separately, to become Alpha Centauri’s equivalent of Civilization’s nations. The player chooses one of them to guide.

So, in addition to the unusually strong plot, we have a heaping dose of political philosophy added to the mix; Alpha Centauri is an unapologetically heady game. Brian Reynolds had attended graduate school as a philosophy major in a previous life, and he drew from that background liberally. The factions’ viewpoints are fleshed out largely through a series of epigrams that appear as you research new technologies, each of them attributed to one of the seven faction leaders, with an occasional quote from Aristotle or Nietzsche dropped in for good measure.

Fossil fuels in the last century reached their extreme prices because of their inherent utility: they pack a great deal of potential energy into an extremely efficient package. If we can but sidestep the 100 million year production process, we can corner this market once again.

— CEO Nwabudike Morgan,

Strategy Session

The factions are:

- Gaia’s Stepdaughters, staunch environmentalists who believe that humanity must learn to live in harmony with nature to avoid repeating the mistakes that led to the ruination of Earth.

- The Human Hive, hardcore collectivists whose only complaint about Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution is that it didn’t go far enough.

- Morgan Industries, hardcore capitalists whose only complaint about Ayn Rand is that she didn’t go far enough.

- The University of Planet, STEM specialists who are convinced that scientific and technological progress alone would correct all that ails society if people would just let it run unfettered and go where it takes them.

- The Lord’s Believers, a fundamentalist sect who are convinced that God will deliver humanity to paradise if we all just pray really hard and abide by a set of stringent, arbitrary dictates.

- The Spartan Federation, who train their children from birth to be hardened, self-sacrificing warriors like the Spartans of old.

- The Peacekeepers, the closest thing to pragmatists in this rogue’s gallery of ideologues; they value human rights, democracy, dialog, and consensus-building, and can sometimes seem just as wishy-washy and ineffectual in the face of militant extremism as the earthly United Nations that spawned them.

Unlike the nations that appear in Civilization I and II, each of the factions in Alpha Centauri has a very significant set of systemic advantages and disadvantages that to a large extent force even a human player to guide them in a certain direction. For example, the Human Hive is excellent at building heavy infrastructure and pumping out babies, but poor at research, and can never become a democracy; the University of Planet is crazily great at research, but its populace has little patience for extended wars and is vulnerable to espionage. Trying to play a faction against type is, if not completely impossible for the advanced player, not an exercise for the faint of heart.

There is a lot of food for thought in the backstory of a ruined Earth and the foreground story of an angry Planet, as there is in the factions themselves and their ideologies, and trust me when I say that plenty of people have eaten their fill. Even today, more than a quarter-century after Alpha Centauri’s release, YouTube is full of introspective think-pieces purporting to tell us What It All Means.

Indeed, if anything, the game’s themes and atmosphere resonate more strongly today than they did when it first came out in February of 1999, at which time the American economy was booming, our world was as peaceful and open as it has ever been, and the fantasy that liberal democracy had won the day and we had reached the end of history could be easily maintained by the optimistic and the complacent. Alas, today Alpha Centauri feels far more believable than Civilization and its sang-froid about the inevitability of perpetual progress. These days, Alpha Centauri’s depiction of bickering, bitterly entrenched factions warring over the very nature of truth, progressing not at all spiritually or morally even as their technology runs wild in a hundred different perilous directions, strikes many as the more accurate picture of the nature of our species. People play Alpha Centauri to engage with modern life; they play Civilization to escape from it.

The original Civilization was ahead of the curve on global warming, prompting accusations of “political correctness” from some gamers. Paying heed to the environment is even more important in Alpha Centauri, since failing to do so can only aggravate Planet’s innate hostility. The “Eco-Damage” statistic is key.

That said, we must also acknowledge that Alpha Centauri is disarmingly good at mirroring the beliefs of its players back at them. Many people like to read a strong environmentalist message in the game, and it’s not hard to see why. Your struggles with the hostile Planet, which is doing everything it can to protect itself against the alien parasites on its surface, is an extreme interpretation of the Gaia hypothesis about Earth, even as Alpha Centauri’s “transcendence” victory — the equivalent of Civilization’s tech victory that got us here in the first place — sees humanity overcoming its estrangement from its surroundings to literally become one with Planet.

For what it’s worth, though, in his “Designer’s Notes” at the back of the Alpha Centauri manual, the one message that Brian Reynolds explicitly states that he wishes for the game to convey is a very different one: that we ought to be getting on with the space race. “Are we content to stew in our collective juices, to turn inward as our planet runs inexorably out of resources?” he asks. “The stars are waiting for us. We have only to decide that it’s worth the effort to go there.” Personally, although I have nothing against space exploration in the abstract, I must say that I find the idea of space colonization as the solution to the problem of a beleaguered Planet Earth shallow if not actively dangerous. Even in the best-case scenario, many, many generations will pass before a significant number of humans will be able to call another celestial object their permanent home. In the meantime, there is in fact nothing “inexorable” about polluting our own planet and bleeding it dry; we have the means to stop doing so. To steal a phrase from Reynolds, we have only to decide that it’s worth the effort.

But enough with the ideology and the politics, you might be saying — how does Alpha Centauri play as a game? Interestingly, Brian Reynolds himself is somewhat ambivalent on this subject. He recalls that he set aside a week just to play Civilization II after he pronounced that game done, so thrilled was he at the way it had come out. Yet he says that he could barely stand to look at Alpha Centauri after it was finished. He was very proud of the world-building, the atmosphere, the fiction. But he didn’t feel like he had quite gotten the gameplay mechanics sorted so that they fully supported the fiction. And I can kind of see what he means.

To state the obvious: the gameplay of Alpha Centauri is deeply indebted to Civilization. Like, really, really indebted. So indebted that, when you first start to play it, you might be tempted to see it as little more than a cosmetic reskin. The cities of Civilization are now “bases”; the “goody-hut” villages are now supply pods dropped by the Unity in its last hours of life; barbarian tribes are native “mind worms”; settler engineers are terraformers; money is “energy credits”; Wonders of the World are Secret Projects; etc., etc. It is true that, as you continue to play, some aspects will begin to separate themselves from their inspiration. For example, and perhaps most notably, the mind worms prove to be more than just the early-game annoyance that Civilization’s barbarians are; instead they steadily grow in power and quantity as Planet is angered more and more by your presence. Still, the apple never does roll all that far from the tree.

Very early in a game of Alpha Centauri, when only a tiny part of the map has been revealed. Of all the contrivances in the fiction, this idea that you could have looked down on Planet from outer space and still have no clue about the geography of the place might be the most absurd.

Where Alpha Centauri does innovate in terms of its mechanics, its innovations are iterative rather than transformative. The most welcome improvement might be the implementation of territorial borders for each faction, drawn automatically around each cluster of bases. To penetrate the borders of another faction with your own units is considered a hostile act. This eliminates the weirdness that dogged the first two iterations of Civilization, which essentially saw your empire as a linked network of city-states rather than a contiguous territorial holding. No longer do the computer players walk in and plop down a city… err, base right in the middle of five of your own; no longer do the infantry units of your alleged allies decide to entrench themselves on the choicest tile of your best base. Unsurprisingly given the increased verisimilitude they yielded, national borders would show up in every iteration of the main Civilization series after Alpha Centauri.

Other additions are of more dubious value. Brian Reynolds names as one of his biggest regrets his dogged determination to let you design your own units out of the raw materials — chassis, propulsion systems, weapons, armor, and so on — provided by your current state of progression up the tech tree, in the same way that galaxy-spanning 4X games like Master of Orion allowed. It proved a time-consuming nightmare to implement in this uni-planetary context. And, as Reynolds admits, it’s doubtful how much it really adds to the game. All that time and effort could likely have been better spent elsewhere.

When I look at it in a more holistic sense, it strikes me that Alpha Centauri got itself caught up in what had perchance become a self-defeating cycle for grand-strategy games by the end of the 1990s. Earlier games had had their scope and complexity strictly limited by the restrictions of the relatively primitive hardware on which they ran. Far from being a problem, these limits often served to keep the game manageable for the player. One thinks of 1990’s Railroad Tycoon, another Sid Meier classic, which only had memory enough for 35 trains and 35 stations; as a result, the growth of your railroad empire was stopped just before it started to become too unwieldy to micro-manage. Even the original Civilization was arguably more a beneficiary than a victim of similar constraints. By the time Brian Reynolds made Civilization II, however, strategy games could become a whole lot bigger and more complex, even as less progress had been made on finding ways to hide some of their complexity from the player who didn’t want to see it and to give her ways of automating the more routine tasks of empire management. Grand-strategy games became ever huger, more intricate machines, whose every valve and dial still had to be manipulated by hand. Some players love this sort of thing, and more power to them. But for a lot of them — a group that includes me — it becomes much, much too much.

To its credit, Alpha Centauri is aware of this problem, and does what it can to address it. If you start a new game at one of the two lowest of the six difficulty levels, it assumes you are probably new to the game as a whole, and takes you through a little tutorial when you access each screen for the first time. More thoroughgoingly, it gives you a suite of automation tools that at least nod in the direction of letting you set the high-level direction for your faction while your underlings sweat the details. You can decide whether each of your cities… err, bases should focus on “exploring,” “building,” “discovering,” or “conquering” and leave the rest to its “governor”; you can tell your terraforming units to just, well, terraform in whatever way they think best; you can even tell a unit just to go out and “explore” the blank spaces on your map.

Sadly, though, these tools are more limited than they might first appear. The tutorials do a decent job of telling you what the different stuff on each screen is and does, but do almost nothing to explain the concepts that underlie them; that is to say, they tell you how to twiddle a variety of knobs, but don’t tell you why you might want to twiddle them. Meanwhile the automation functions are undermined by being abjectly stupid more often than not. Your governor will happily continue researching string theory while his rioting citizens are burning the place down around his ears. You can try to fine-tune his instructions, but there comes a point when you realize that it’s easier just to do everything yourself. The same applies to most of the automated unit functions. The supreme booby prize has to go to the aforementioned “explore” function. As far as I can determine, it just causes your unit to move in a random direction every turn, which tends to result in it chasing its tail like a dog that sat down in peanut butter rather than charging boldly into the unknown.

This, then, is the contradiction at the heart of Alpha Centauri, which is the same one that bothers me in Civilization II. A game that purports to be about Big Ideas demands that you spend most of your time engaged in the most fiddly sort of busywork. I hasten to state once again that this is not automatically a bad thing; again, some people enjoy that sort of micro-management very much. For my own part, I can get into it a bit at the outset, but once I have a dozen bases all demanding constant attention and 50 or 60 units pursuing their various objectives all over the map, I start to lose heart. For me, this problem is the bane of the 4X genre. I’m not enough of an expert on the field to know whether anyone has really come close to solving it; I look forward to finding out as we continue our journey through gaming history. As of this writing, though, my 4X gold standards remain Civilization I and Master of Orion I, because their core systems are simple enough that the late game never becomes completely overwhelming.

Speaking of Master of Orion: alongside the questionable idea of custom-built units, Alpha Centauri also lifts from that game the indubitably welcome one of a “diplomatic victory,” which eliminates the late-game tedium of having to hunt down every single enemy base and unit for a conquest victory that you know is going to be yours. If you can persuade or intimidate enough of the other factions to vote for you in the “Planetary Council” — or if you can amass such a large population of your own that you can swamp the vote — you can make an inevitability a reality by means of an election. Likewise, you can also win an “economic” victory by becoming crazy rich. These are smart additions that work as advertised. They may only nibble at the edges of the central problem I mentioned above, but, hey, credit where it’s due.

Aesthetically, Alpha Centauri is a marked improvement over Civilization II, which, trapped in the Windows 3.1 visual paradigm as it was, could feel a bit like “playing” a really advanced Excel spreadsheet. But Alpha Centauri also exhibits a cold — not to say sterile — personality, with none of the goofy humor that has always been one of Civilization’s most underrated qualities, serving to nip any pretentiousness in the bud by reminding us that the designers too know how silly a game that can pit Abraham Lincoln against Mahatma Gandhi in a nuclear-armed standoff ultimately is. There’s nothing like that understanding on display in Alpha Centauri — much less the campy troupe of live-action community-theater advisors who showed up to chew the scenery in Civilization II. The look and feel of Alpha Centauri is more William Gibson than Mel Brooks.

While the aesthetics of Alpha Centauri represent a departure from what came before, we’re back to the same old same old when it comes to the actual interface, just with more stuff packed into the menus and sub-menus. I’m sure that Brian Reynolds did what he could, but it will nevertheless come off as a convoluted mess to the uninitiated modern player. It’s heavily dependent on modes, a big no-no in GUI design since the days when the Apple Macintosh was a brand new product. If you’re anything like me, you’ll accidentally move a unit about ten times in any given evening of play because you thought you were in “view” mode when you were actually in “move” mode. And no, there is no undo function, a feature for which I’d happily trade the ability to design my own units.

The exit dialog is one of the few exceptions to Alpha Centauri as a humor-free zone. “Please don’t go,” says a passable imitation of HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey. “The drones need you.” Note that this is a game in which you click “OK” to cancel. Somewhere out there a human-factors interface consultant is shuddering in horror.

As so often happens in reviews like these, I find now that I’ve highlighted the negative here more than I really intended to. Alpha Centauri is by no means a bad game; on the contrary, for some players it is a genuinely great one. It is, however, a sharply bifurcated game, whose fiction and gameplay are rather at odds with one another. The former is thoughtful and bold, even disturbing in a way that Civilization never dared to be. The latter is pretty much what you would expect from a game that was promoted as “Civilization in space,” and, indeed, that was crafted by the same man who gave us Civilization II. A quick survey of YouTube reveals the two halves of the whole all too plainly. Alongside those earnest think-pieces about What It All Means, there are plenty of videos that offer tips on the minutiae of its systems and show off the host’s skill at beating it at superhuman difficulty levels, untroubled by any of its deeper themes or messages.

As you’ve probably gathered from the tone of this article, Alpha Centauri leaves me with mixed feelings. I’m already getting annoyed by the micro-management by the time I get into the mid-game, even as I miss a certain magic sauce that is part and parcel of Civilization. There’s something almost mythical or allegorical about going from inventing the wheel to sending a colony ship on its way out to the stars. Going from Biogenetics to the “Threshold of Transcendence” in Alpha Centauri is less relatable. And while the story and the additional philosophical textures that Alpha Centauri brings to the table are thought-provoking, they can only be fully appreciated once. After that, you’re mostly just clicking past the interludes and epigrams to get on to building the next thing you need for your extraterrestrial empire.

In fact, it seems to me that Alpha Centauri at the gameplay level favors the competitive player more than the experiential one; being firmly in the experiential camp myself, this may explain why it doesn’t completely agree with me. It’s a more fiercely zero-sum affair than Civilization. Those players most interested in the development side of things can’t ensure a long period of peaceful growth by choosing to play against only one or two rivals. All seven factions are always in this game, and they seem to me far more prone to conflict than those of Civilization, what with the collection of mutually antithetical ideologies that are such inseparable parts of their identities. Suffice to say that the other faction leaders are exactly the self-righteous jerks that rigid ideological extremists tend to be in real life. This does not lend itself to peace and harmony on Planet even before the mind worms start to rise up en masse. Even when playing as the Peacekeepers, I found myself spending a lot more time fighting wars in Alpha Centauri than I ever did in Civilization, where I was generally able to set up a peaceful, trustworthy democracy, forge strong diplomatic and trading links with my neighbors, and ride my strong economy and happy and prosperous citizenry to the stars. Playing Alpha Centauri, by contrast, is more like being one of seven piranhas in a fishbowl than a valued member of a community of nations. If you can find one reliable ally, you’re doing pretty darn well on the diplomatic front. Intervals of peace tend to be the disruption in the status quo of war rather than the other way around.

There was always an understanding at Firaxis that, for all that Alpha Centauri was the best card they had to play at that point in time from a commercial standpoint, its sales probably weren’t destined to rival those of Civilization II. For the Civilization franchise has always attracted a fair number of people from outside the core gaming demographics, even if it is doubtful how many of them really buckle down to play it.

Nonetheless, Alpha Centauri did about as well as one could possibly expect after its release in February of 1999. (Electronic Arts would surely have preferred to have the game a few months earlier, to hit the Christmas buying season, but one of the reasons Firaxis had been founded had been to avoid such compromises.) Sales of up to 1 million units have been claimed for it by some of the principals involved. Even if that figure is a little inflated, as I suspect it may be, the game likely sold well into the high hundreds of thousands.

By 1999, an expansion pack for a successful game like Alpha Centauri was almost obligatory. And indeed, it’s hard to get around the feeling that Alpha Centauri: Alien Crossfire, which shipped in October of that year, was created more out of obligation than passion. Neither the navel-gazers nor the zero-summers among the original game’s fan base seem all that hugely fond of it. Patched together by a committee of no fewer than eight designers, with the name of Brian Reynolds the very last one listed, it adds no fewer than seven new factions, which only serve to muddy the narrative and gameplay waters without adding much of positive interest to the equation; the two alien factions that appear out of nowhere seem particularly out of place. If you ask me, Alpha Centauri is best played in its original form — certainly when you first start out with it, and possibly forever.

Be that as it may, the end of the second millennium saw Firaxis now firmly established as a studio and a brand, both of which would prove very enduring. The company remains with us to this day, still one of the leading lights in the field of 4X strategy, the custodian of the beloved Civilization…

Yes, Civilization. For their next big trick, Firaxis was about to get the chance to make a game under the name that they thought they’d left behind forever when they said farewell to MicroProse.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The book Sid Meier’s Memoir!: A Life in Computer Games by Sid Meier with Jennifer Lee Noonan. Computer Gaming World of August 1996, January 1998, September 1998, April 1999, and January 2000; Next Generation of July 1997; Retro Gamer 241. Also the Alpha Centauri manual, one of the last examples of such a luxuriously rambling 250-page tome that the games industry would produce.

Online sources include Soren Johnson’s interview of Brian Reynolds for his Designer’s Notes podcast and Reynolds’s appearance on the Three Moves Ahead podcast (also with Soren Johnson in attendance). The YouTube think-pieces I mentioned include ones by GaminGHD, Waypoint, Yaz Minsky, CairnBuilder, and Lorerunner.

Where to Get It: Alpha Centauri and its expansion Alien Crossfire are available as a single digital purchase at GOG.com.