The future is boring.— Zack Norman

Prologue: Scenes from an Italian Restaurant

One day in the fall of 1995, two Activision game designers by the names of Sean Vesce and Zack Norman went out to lunch together at their favorite Italian joint. Both had just come off of MechWarrior 2: 31st Century Combat, an action-packed “simulation” of giant rock-em, sock-em robots that took place in the universe of the popular tabletop game BattleTech. They had done their jobs well: slick and explosive, MechWarrior 2 had become the game of the hour upon its release the previous August, the perfect alternative for players who had been entranced by the Pandora’s Box of 3D mayhem that had been cracked open by DOOM but who were growing a little bored with the recent onslaught of me-too DOOM clones.

There was only one cloud on the horizon: Activision knew already that they wouldn’t be allowed to make a MechWarrior 3. Their rights to BattleTech were soon to expire and were not going to be renewed, what with FASA, the company which owned the tabletop game, having decided to start a studio of its own, FASA Interactive, to produce digital incarnations of its tabletop properties. Activision’s owner Bobby Kotick, who was quickly making a name for himself as one of the savviest and most unsentimental minds in gaming, had accordingly issued orders to his people to milk MechWarrior 2 and its engine, which had required a great deal of time and expense to create, for all they were worth while the opportunity was still there. This would result in two expansion packs for the core game before the curtain fell on the license. Meanwhile Vesce and Norman were tasked with coming up with an idea for another “vehicular combat game” that could be developed relatively quickly and cheaply, to take advantage of the engine one last time before it became hopelessly out of date. They had gone to lunch together today to discuss the subject.

Or Vesce had, at any rate. Norman was still basking in the bonus he had earned from MechWarrior 2, the biggest check he had ever seen with his name on it. A diehard Mopar fanboy, he had just about decided to buy himself a vintage muscle car with his windfall. He had thus brought an Auto Trader magazine along with him to the restaurant, and kept flipping through the pages distractedly while Vesce threw out game ideas, none of which quite seemed right. (“What about a helicopter sim?”) But Norman suddenly stopped turning the pages when he came across a 1970 Plymouth Barracuda. “Is that the car?” asked Vesce, a little disinterestedly.

Then he saw the look on Norman’s face — the look of a man who had finally seen something that had been staring him in the face for most of the last hour. It was, after all, a vehicular combat game they had been tasked with making. “No,” said Norman. “That’s the game!” And so Interstate ’76, one of the freshest and cleverest mass-market computer games of the late 1990s, was born.

The road to that memorable lunch stretches all the way back to 1980, when the excitement around Dungeons & Dragons was inspiring many tabletop gamers to start companies in the role-playing space which it had opened up. Among their number was a pair of Chicago boys named Jordan Weisman and L. Ross Babcock. They formed FASA that year; the acronym was an elaborate high-school joke that owed a debt to the Marx Brothers, standing for “Freedonian Aeronautics and Space Administration.” They scrounged together $300 in seed capital, just enough to run off a bunch of copies of an adventure module they had created for Traveller, the most popular of the early science-fiction RPGs. Then they took their adventure to that year’s Gen Con to sell it, sleeping in their van in the parking lot for lack of the funds to pay for a hotel room.

From those humble beginnings, FASA scraped and clawed their way within two years to landing a stunner of a deal: to make a tabletop RPG based on Star Trek. It shipped in 1983, whereupon critics lauded the system for its simplicity and approachability, and for the way it captured the idealistic essence of Star Trek at its best, with its ethos of violence as a last rather than a first resort. (A comparison might be mooted with Call of Cthulhu, another tabletop RPG that turned the Dungeons & Dragons power-gaming approach on its head in the service of a very different mission statement.) “To make Star Trek: The RPG a Klingon shoot would be in violation of everything the series represented,” said Guy W. McLimore Jr., one of the game’s trio of core designers. “Man-to-man-combat and starship-combat systems were important, and had to be done right, but these were to take a backseat to the essential human adventure of space exploration.”

FASA supported their Star Trek RPG lavishly, with rules supplements, source books, and adventure modules galore during the seven years they were allowed to hang onto the license. Many a grizzled tabletop veteran will still tell you today that FASA’s Star Trek was as good as gaming on the Final Frontier ever got. When you did engage in spaceship combat, for example, the game did an uncanny job of putting you in the shoes of your character standing on the bridge, rather than relegating you to pushing cardboard counters around on a paper map in the style of Star Fleet Battles.

Still, if you were more interested in shooting things than wrestling with ethical dilemmas, FASA had you covered there as well. The same year as the Star Trek RPG, they published Combots. Inspired by Japanese anime productions that enjoyed no more than a tiny following in the United States as yet, it was a board game of, as the name would imply, combat between giant robots, co-designed by Jordan Weisman himself and one Bill Fawcett.

They refined and added to the concept the following year with a miniatures-based strategy game called Battledroids. A year after that, Battledroids became BattleTech in response to legal threats from Lucasfilm of Star Wars fame, who felt the term “droid” rightfully belonged to them alone. (“I politely wrote back,” says Weisman, “to point out that Isaac Asimov had been using the word ‘android’ since something like 1956. They wrote back to point out that they had a lot more lawyers than we did.”)

By now, the wave of Japanese giant robots had fully broken Stateside; the Saturday morning cartoon lineup showcased Transformers prominently, and that show’s associated line of action figures was flying off store shelves even faster than their Star Wars brethren. BattleTech was the right game at the right time, perfect for people who were too old to play with action figures that were intended as mere toys but still young enough at heart to appreciate duels between gargantuan armor-plated “mechs” bristling with laser cannons, missile launchers, and just about every other imaginable form of futuristic destruction.

From the beginning, BattleTech incorporated some RPG elements. It came complete with a detailed setting whose history was laid out in a timeline that spanned over a millennium of humanity’s future. Likewise, players were encouraged to keep and slowly improve the same mech over the course of many battles. At the same time, though, the game required no referee and was quick to pick up and play, keeping the focus squarely on the combat. In 1986, FASA released a supplement called MechWarrior that moved the system further into RPG territory, for those who so desired, adding the missing referee back into the equation. It placed players in the roles of individual mech pilots, a new breed of knights in shining armor who had much in common with their Medieval ancestors, being fixated on chivalry, noblesse oblige, and blood feuds. BattleTech and MechWarrior spawned a cottage industry, one which by the late 1980s rivaled the Star Trek RPG in terms of its contributions to FASA’s bottom line as well the sheer quantity of supplements that were available for it, full of background information, scenarios, and most of all cool new mechs and mech kit, things its fans could never seem to get enough of.

FASA had had the opportunity to study up close and personal the way that a huge property like Star Trek sprawled across the ecosystem of media: television, movies, books, comics, toys, tabletop and digital games. They saw no reason that BattleTech shouldn’t follow its example. Thus they commissioned a BattleTech comic, and hired the tabletop-gaming veteran Michael Stackpole to write a series of BattleTech novels. If the latter read like a blow-by-blow description of someone’s gaming session, so much so that you could almost hear the dice rolling in the background… well, that was perhaps a feature rather than a bug in the eyes of the target audience.

Only three of his hastily loosed missiles made their target, but those hit with a vengeance. One exploded into one of the Rifleman’s autocannon ejection ports, fusing the ejection mechanism. The other missiles both slammed into the radar wing whirling like a propeller above the ‘Mech’s hunched shoulders. The first explosion froze the mechanism in place. The second blast left the wing hanging by thick electrical cables…

Then, too, FASA didn’t neglect the digital space. From 1987, Jordan Weisman devoted most of his energy to the creation of “BattleTech Centers,” which played host to virtual-reality cockpits where players could take on the role of mech pilots far more directly and viscerally than any mere tabletop game would allow. A radically ambitious idea that wasn’t at all easy to bring to fruition, the first BattleTech Center didn’t open until 1990, in Chicago’s North Pier Mall. But it was very successful once it did, selling 300,000 tickets for time in one of its sixteen cockpits over its first two years. After a cash injection from the Walt Disney family, this proof of concept would lead to at least 25 more BattleTech Centers in the United States and Japan by the turn of the millennium.

And then there was also digital BattleTech for the home. FASA signed a deal with Activision in 1987, giving them the right to make BattleTech games for personal computers for the next ten years. The first fruit of that deal appeared in late 1988 under the name of BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception. It was published under the Infocom imprint, but that storied text-adventure specialist, a somewhat reluctant member of the Activision family since 1986, had little to do with it; the real developer was Westwood Associates. In its review, Computer Gaming World magazine called The Crescent Hawk’s Inception a cross between Ultima and the BattleTech board game, and this strikes me as a fair description. You wandered the world, following the bread-crumb trail of the story line, building up your finances and your skills, recruiting companions, and improving your collection of mechs, the better to fight battles which were quite faithful to the tabletop game, right down to being turn-based from an overhead perspective. It wasn’t a bad game, but it wasn’t an amazing one either, feeling more workmanlike than truly inspired. All indications are that it sold fairly modestly.

One year later, Activision returned with another BattleTech game. Developed by Dynamix, MechWarrior borrowed the name of FASA’s RPG expansion to the core tabletop game, yet was actually less of a CRPG than its predecessor had been. You still wandered from place to place chasing the plot and searching out battles, but the latter were now placed front and center, and had more in common with the still-in-the-works BattleTech Centers than the tabletop game, taking place in real time from a first-person perspective. MechWarrior sold much better than The Crescent Hawk’s Inception, proving that many others agreed with Computer Gaming World‘s Johnny L. Wilson when he said that this was the kind of BattleTech computer game “I was looking for.”

It was followed another year later by another Westwood game, a direct sequel to The Crescent Hawk’s Inception entitled The Crescent Hawk’s Revenge. In spite of its sequel status, it dispensed with the CRPG aspects entirely, in favor of a simple branching mission tree. These were shown once again from an overhead perspective, but played out in real time rather than in turns. These qualities make the game stand out as an interesting progenitor to the full-fledged real-time-strategy genre, which Westwood themselves would invent less than two years later with Dune II. In the meantime, Computer Gaming World declared it “the game every BattleTech devotee has been waiting for.”

Unfortunately for everyone, Activision imploded just weeks after publishing The Crescent Hawk’s Revenge in late 1990, brought down by an untimely patent-infringement lawsuit and a long string of bad decisions on the part of CEO Bruce Davis. The company was rescued from the brink of oblivion by the opportunistic young wheeler and dealer Bobby Kotick, who had been itching for a computer-game publisher of his very own for several years already. He declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy, moved the whole operation from Silicon Valley to Los Angeles, cut its staff from 150 to eight, and kept it alive by digging deep into his capacious bag of tricks to wheedle just a little more patience out of its many creditors, a few months at a time.

It is one of the little-known ironies of modern gaming that Bobby Kotick’s Activision — the same Activision that brought in revenues of almost $9 billion in 2021 — owes its ongoing existence to the intellectual property of Infocom, a company which in its best year as an independent entity brought in $10 million in revenue. Casting about for a product he could release quickly to bring in some much-needed cash, Kotick hit upon Infocom’s 1980s text-adventure catalog. He published all 35 of the games in question in two shovelware collections, The Lost Treasures of Infocom I and II, the first of which alone sold at least 100,000 copies at $60 a pop and a profit margin to die for. He followed that triage operation up by going all-in on Return to Zork, a state-of-the-art graphic adventure that capitalized equally on the excitement over multimedia CD-ROM and older gamers’ nostalgia for the bygone days of a purely textual Great Underground Empire.

But if the Lost Treasures stopped the bleeding in 1992 and Return to Zork took the patient off life support in 1993, it was MechWarrior 2 in the summer of 1995 that announced Kotick’s Activision to be fully restored to rude health, once again a marquee publisher of top-shelf gamer’s games that didn’t need to shirk comparisons with anyone else’s.

That said, actually making MechWarrior 2 had been a rather tortured process. Knowing full well that the first MechWarrior had been the old Activision’s last real hit, Kotick would have preferred to have had the sequel well before 1995. However, Dynamix, the studio that had made the first game, had been bought by Activision’s competitor Sierra in 1990. Kotick thus decided to do the sequel in-house, initiating the project already by the end of 1992. It was ill-managed and under-funded by the still cash-strapped company. Artist Scott Goffman later summed up the problems as:

- Over-eager PR people hyping a game that was not even close to being done. This led to forced promises of release dates that were IMPOSSIBLE to make.

- Lack of a design. There was no clear direction for the first year and a half on the game, and no solid style.

- Featuritis. A disease that often afflicts game developers, causing them to want to keep adding more and more features to a game, rather than debugging and shipping what they already have.

- Morale. As they fell further and further behind schedule, the programmers and artists felt less and less inclined to produce. This led to departures.

By early 1994, the entire original team had left, forcing Activision to all but start over from scratch. The project now had such a bad odor about it that, when producer Josh Resnick was asked to take it over, his first instinct was to run the other way as fast as he could: “I actually thought this was a demotion and went so far as to ask if I had done something wrong.”

To his credit, though, it all started to come together after he bit the bullet and took control. He brought Sean Vesce and Zack Norman aboard to tighten up the design, combining elements of the last two licensed BattleTech computer games to arrive at a finished whole that was superbly suited to the post-DOOM market: the first-person action of MechWarrior 1 and the no-nonsense, straightforward mission tree of The Crescent Hawk’s Revenge. (Or rather missions trees in this case: MechWarrior 2 had two campaigns, each from the point of view of a different clan.) And everything was suitably updated to take advantage of the latest processors, graphics cards, and sound cards, of course.

It had now been almost five years since the last boxed BattleTech game for personal computers. In the interim, FASA, having lost their Star Trek license in 1989, had made the franchise their number-one priority. It was more popular than ever, encompassing more than 100 individual tabletop-gaming products, plus novels and comics, a line of toys, and even a televised cartoon series. Meanwhile a downloadable multi-player BattleTech computer game, developed by the online-gaming pioneer Kesmai, was doing very good business on the GEnie subscription service. So, there was a certain degree of pent-up demand among the FASA faithful for a new BattleTech computer game that you didn’t have to pay to play by the minute, even as there was also a fresh audience of rambunctious young men who had come to computer gaming through the likes of DOOM, who might not know BattleTech from Battle Isle, but who thought the idea of giant battling robots was hella cool in its own right.

MechWarrior 2 disappointed the expectations of neither its creators nor its consumers; it exploded out of the gate like a mech in its death throes, generating sales that made everything Bobby Kotick’s Activision had done before seem quaint. The party continued in 1996, when Activision released a free add-on that made online multiplayer games a possibility, thus destroying the Kesmai BattleTech‘s market at a stroke. When the first hardware-accelerated 3D graphics cards began to appear in the summer of 1996, MechWarrior 2 was there once again. With his customary savvy, Kotick went to the makers of these disparate, mutually incompatible cards one by one, offering them a special version of one of the most popular games of the era, optimized to look spectacular with their particular card, ripe for packing right into the box along with it. All they had to do was pay Activision to make it for them. And pay they did; MechWarrior 2 became the king of the 3D-card pack-in games, a strange species that would exist for only a sharply limited period of time, until the switch from MS-DOS to Windows 95 as computer gaming’s standard platform made the need for all these custom builds for incompatible hardware a thing of the past. But it was very, very good for Activision while it lasted.

And then there was that other game that was to be made using the MechWarrior 2 engine. I must confess that it’s with that game that my heart really lies, and so it’s there that we’ll turn now.

Part 2: Feel Like Funkin’ It Up

When Sean Vesce and Zack Norman stood up from what had proved to be an inordinately long lunch, they had a pretty good idea of what they wanted Interstate ’76 to be. It was to be “a game with soul,” as Vesce puts it — soul in more ways than one. They wanted to make a tribute to the television shows of the 1970s, in which irreverent two-fisted heroes with names like Rockford and Ponch had scoured the nation’s highways and byways of ne’er-do-wells, sharing top billing in the minds of the audience with the vehicles they drove. Children of the 1980s that the two friends were, those shows had been one of the entertainment staples of their youth, to be enjoyed along with a cold soda and a sandwich as afternoon reruns after a long day at school. “We wanted to make a game that could capture a mood in a way that goes beyond just lighting things on fire and blowing them up,” says Norman, in a not-so-oblique reference to the game he worked on just before Interstate ’76. The new game’s soul was to be found as much as anywhere in the soundtrack, which was to draw from the 1970s heyday of blaxploitation flicks in the theaters as well as television.

In short, Vesce and Norman wanted to steer clear of all the usual gaming clichés, even as they embraced a whole pile of older ones, like tires that inexplicably squealed on dirt roads. They were adamant that, although it would feature battling automobiles, this was not to be yet another post-apocalyptic exercise; surely games had milked The Road Warrior enough by now. No, in their dystopian wasteland the bad guys would be OPEC and their mobster cronies, who were starving the nation of the gasoline it needed to keep its Mopar Hemis humming. It was to be, in other words, an exaggerated version of what was really going on in 1976, when the last of the muscle cars were being strangled by federal fuel-economy standards and the mad scientist’s tangle of emissions dampeners that was now required under each and every American hood. Only in this timeline vintage American muscle might just be able to win out rather than shuffle quietly off to extinction.

All of this may not have been a recipe for high art, but it was as foreign a notion for the increasingly risk-averse, perpetually lily-white executives of the games industry as an avant-garde character study would be to Jerry Bruckheimer. Vesce and Norman had a damnably hard time selling it to the suits; Vesce admits that “the first pitch meeting was disastrous.” But slowly they made headway. After all, they noted, it wasn’t as if the young males who constituted the heart of the gaming demographic wouldn’t get where they were coming from; plenty of them had grown up with the same afternoon television as Vesce and Norman. And by reusing the MechWarrior 2 engine, keeping the scope modest, and avoiding such misbegotten indulgences as live-action cut scenes, they could get by with a relatively small development team, a compressed development cycle, and a reasonable development budget. Thanks to MechWarrior 2‘s success, Activision finally had a little bit of cash on hand to take a flier on something a little bit different, without the fate of the whole company hanging on the outcome. First the Director of Creative Affairs saw the light. Then, one by one, his colleagues in business suits fell into line. The game got the green light.

Making Interstate ’76 proved a happy experience for everyone involved. And in the end, they delivered exactly the game they had promised, more or less on time and on budget. It was released by Activision in the spring of 1997, garnering very favorable reviews and solid if not stupendous sales, despite graphics that were the state of the art of two years ago.

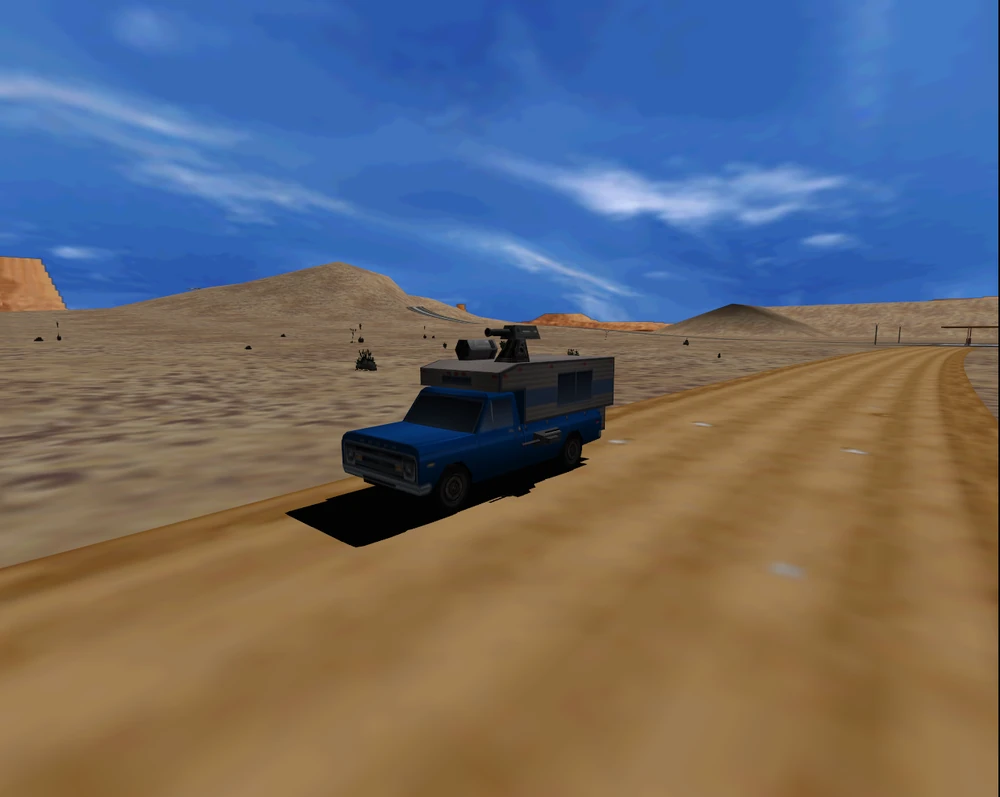

The only reason to play the game today is its story mode — or, the “T.R.I.P.” (“Total Recreational Interactive Production”), as it prefers to call it. This T.R.I.P. takes us to the desolated landscapes of West Texas and New Mexico (whose lack of such complications as trees makes them much easier for the engine to render). Your avatar is a white soul brother by the name of Groove Champion, with a rather glorious handlebar pornstache and a preference for huge collars and unbuttoned shirt fronts. His sister Jade — “Jade was always a better racer than me, man,” he confesses — has just been violently killed. Groove has inherited her car, a 1970 Plymouth Barracuda like the one Zack Norman stumbled across in that Auto Trader on that memorable day in an Italian restaurant. (Well, it’s actually called a “Picard Piranha” in the game; all of the cars were rebranded for legal reasons, but all are based on real-world models that the aficionado will readily recognize.) Groove is no natural-born killer, and it takes quite some cajoling from Jade’s best friend, a spiffy dude named Taurus, to convince him to hit the road to find her killer and avenge her death.

Taurus is the funkiest cat ever to appear in a game. Vesce calls him “the embodiment of the attitude and soul we were trying to inject into the game. He was Shaft, Super Fly and Samuel L. Jackson all rolled into one. Plus, he was a poet.” Indeed, one of your options in your car is to “ask Taurus for a poem.” The verses he intones over the CB radio when you do so are… not too bad, actually.

Looking out the window of your room onto a wet rainy day

Main street under a slate grey afternoon sky

The light on your face is soft and dim under the lace curtain

And the streets are empty

In the distance, there is a flash and a rumble

Clouds sail the sky like giant wooden ships

On a blackened evergreen sea

Capped with foam

(All of the poems are the work of Zack Norman.)

Soon after meeting Taurus, you meet the story’s third and final good guy, a seemingly slow-witted country bumpkin of a mechanic named Skeeter who, in one of the game’s best running gags, turns out to have a savant-like insight on the things that really matter. Add in Antonio Malochio, the oily Mafia don and OPEC stooge who eventually emerges as Jade’s murderer, and the cast of characters is complete. Interstate ’76 is a masterclass in tight, effective videogame storytelling, giving you exactly what you need to motivate you through its seventeen missions — or “scenes,” as it prefers to call them — and nothing that you don’t. (In this sense as in many others, it’s the polar opposite of Realms of the Haunting, the hilariously piebald everything-but-the-kitchen-sink “epic” I wrote about in my last article.)

From the moment you start the game, everything you see and hear draws you into its world; nothing jars with anything else. The soundtrack is credible 1970s funk, where the booty-shaking bass lines do the heavy lifting. It was a side gig for Arion Salazar, the bassist for Third Eye Blind, whose first hit single was climbing the music charts at the same time Interstate ’76 was on the games charts. As its pedigree would suggest, the music was recorded in a real studio on real instruments by a solid band of real pros.

A Gallery of Fine Motorized Transport

If you can name all of the vehicles above, your gearhead credentials are impeccable.

In order to keep everything seamless, Vesce and Norman originally wanted to have the cut scenes run in the game engine itself, presaging the approach that Half-Life would employ to such revolutionary effect more than a year later. When this proved impractical, they deliberately made the cut scenes look like they were coming out of the same engine. Somehow the characters here, lacking though they may be such purportedly essential details as eyes and lips, have more character than the vast majority of photo-realistic gaming specimens, proof that good aesthetics and high resolutions are not one and the same. By keeping its visuals all of a piece, the game makes the standard loop of “play a level, watch a cut scene,” which was already becoming tedious in many contexts by 1997, feel much more organic, like it really is all one story you’re living through.

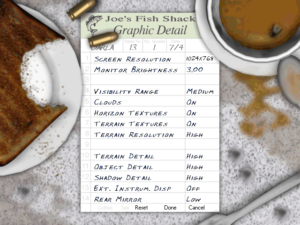

Everything else is fashioned in the same spirit. Everything is diegetic. You upgrade your car between missions by talking it over with Skeeter; your in-mission map had been scrawled on an empty bag of fast-food takeout; even the options menu appears as the check from a roadside restaurant.

Having given praise where it is richly due, I must acknowledge that the gameplay itself is rather less revelatory than that which surrounds it. Unsurprisingly given the origins of the gameplay engine, the cars themselves behave more like BattleTech mechs than real automobiles, even when making allowances for the machine guns and flame throwers that are bolted onto their chassis. Vehicles bounce off of one another and the terrain like Matchbox cars; collisions that ought to leave your Barracuda nothing put a pile of twisted wreckage result in no more more than an artfully crinkled fender. Likewise, the engine doesn’t entirely transcend MechWarrior 2‘s aspirations toward being a real simulation; the controls are a bit fiddly, more Wing Commander than WipEout, and this does clash somewhat with the easygoing immersion of the story line. The worst frustration is your inability to save within missions, some of which are fairly extended exercises. It isn’t much fun to play the first ten minutes of a mission over and over in order to get to the part that’s giving you trouble.

Asked in 1999 about what he would like to have done differently in Interstate ’76, Vesce expressed regrets with which I wholeheartedly agree.

If I could turn back time and do it again, the first thing I would do is make the game more action-oriented, with easier controls, clearer mission objectives, and greater and more frequent rewards. I would greatly simplify the game’s shell, most importantly the vehicle repair screen that players accessed between missions. I talked to a lot of people who were completely baffled the first time they went through. It was far too complex and difficult to use without the manual. I would split some of the missions into multiple missions (especially the first one), and offer a way to save at any point in the game.

Like a number of games I’ve written about recently, Interstate ’76 could have benefited from being released in the era of digital distribution, when the marketplace would have allowed it to be its best self: a four to six hour romp, to be undertaken more for the joy of the thing than the challenge. As it is, the nature of the engine and bygone expectations about value for money and what boxed games “ought” to be gum up the works from time to time even if you play on “Wimp” level, as I was more than happy to do. We probably could have done entirely without the then-obligatory skirmish and multiplayer modes, which pretty clearly weren’t where the developers’ hearts were.

Yet the way that the game recognizes and even leans into its limitations does soften the blow. It makes an inside joke out of the fact that you can’t ever get out of your car, because the engine wasn’t designed for that sort of thing. Jade, Skeeter tells us, made one fatal mistake: “She got out of the car. Don’t ever get out of the car.” Needless to say, he doesn’t need to worry that Groove will do the same.

Interstate ’76 is a breath of fresh air for any 1990s gamer — or 21st-century digital antiquarian — who’s grown tired of the typical strictures of game fictions, of the endless procession of dragons and spaceships and fighter jets and zombies and, yes, even giant robots. In an article written in 1999, Ernest Adams noted that, two years after the release of Interstate ’76, “Taurus may be the only black character with a central role in any computer game today.” That of course speaks to a colossal failure on the part of the industry as a whole, but at least we have this welcome exception to point to.

If you’ll bear with me, I’d like to close this review with two personal anecdotes that might begin to explain why this game hits me right in my sweet spot.

Anecdote #1: I spent the early 1990s working in a record store, back when such places still existed. This was the heyday of grunge, and in the name of pleasing the customers I was forced to listen to way too much flannel-clad whinging, backed by pummeling rhythm sections who thought swinging was something you did on a playground. At the end of a long day of this, it was always a joy for me and my soul sister Lorrie to put on some Althea and Donna or some Spoonie Gee and the Sequence and groove for a while as we closed the store. Coming across this game whilst writing these histories brought the same sweet sense of vive la différence!

Anecdote #2: My second car was a 1965 Ford Mustang, which wound up costing me every bit as much money and trouble as my father told me it would when I bought it. Weirdo that I was, I graduated after selling it to weird foreign cars: a Volkswagen Beetle and camper van, a Datsun 280Z, a Volkswagen GTI. But I had friends who stayed wedded to American muscle, and I was always able to appreciate the basso profondo of a finely tuned V8. I stopped messing around with cars when I moved to Europe in 2009; today I confine my mechanical endeavors to keeping our lawn tractor in good working order. Yet a throaty exhaust note heard through an open window, or just the smell of gasoline in a dimly lit garage, can still take me back to those days of barked shins and grease under the fingernails as surely as a madeleine transported Proust. Add this game to that list as well. I realize now that I lived through the tail end of a period that can never return; we absolutely must wean ourselves off of our addiction to fossil fuels if we’re to continue to make a go of civilization on this long-suffering planet of ours. And that’s okay; change is the essence of existence, as Heraclitus knew more than 2500 years ago, when he wrote that one can never step into the same river twice. Still, there’s no harm in reminiscing sometimes, is there?

All that is just me, though. A more impersonal argument for Interstate ’76 might point to it as a case study in how the best games aren’t really about technology at all. A low-budget affair based on an aging and imperfectly repurposed engine, it was nevertheless all kinds of awesome. For it had that one magic ingredient that most of its wealthier, more attractive peers lacked: it had soul, baby.

Hot rubber eternally pressing against a blackened pavement

A wheel is forever

A car is infinity times four

Postscript: Yesterday, When I Was Young

MechWarrior 2 and Interstate ’76 both proved to be peaks that were impossible to scale a second time, each in its own way.

Activision was indeed forced to give the digital rights to BattleTech to FASA’s new computer-games division, but the latter never managed to thrust its own games into the central spotlight that MechWarrior 2 had enjoyed. FASA itself closed up shop in 2001. “The adventure-gaming world has changed much, and it is time for the founders of FASA to move on,” wrote the old friends Jordan Weisman and L. Ross Babcock in a farewell letter to their fans. BattleTech, however, lives on, under the auspices of WizKids, a new company set up by Weisman. MechWarrior games and other BattleTech games with different titles have continued to appear on computers, but none has ever become quite the sensation that MechWarrior 2 was back in those heady days of the mid-1990s.

Interstate ’76 got one rushed-seeming expansion pack that added support for 3D hardware acceleration — a feature oddly missing from the base game, given its engine’s history — and 20 missions that weren’t tied together by any story line, an approach which the core gameplay arguably wasn’t strong enough to support. Then, in 1999, it got a full-fledged sequel, Interstate ’82, which tried to do for the synth-pop decade what its predecessor had for the decade of funk. But it just didn’t come together somehow, despite Zack Norman once again taking the design reins and despite a much prettier, faster engine. While Interstate ’76 lives on as a cult classic today, Interstate ’82 is all but forgotten. Chalk it up as yet more evidence that advanced technology does not automatically lead to a great game.

If you were to ask my advice, I would suggest that you enjoy Interstate ’76, the only computer game I’ve written about today that transcends the time and circumstances of its creation, and consign the rest to history. But remember: whatever you do, don’t get out of the car.

Where to Get Them: Due doubtless to the complications of licensing, all of the BattleTech and MechWarrior computer games described in this article are out of print. Interstate ’76, however, is available as a digital purchase at GOG.com. Unfortunately, it can be a frustrating game to get working properly on modern Windows, and the version that’s for sale does less than you might expect to help you. In many cases, it seems to degrade rather than fail outright, often in pernicious ways: missions are glitched so as to become impossible to complete, etc. There are solutions out there — I’d suggest starting on the GOG.com forums and the PC Gaming Wiki — but all require some technical expertise. Further, different solutions seem to work (and not work) on different computers, making it impossible for me to point you to a single foolproof set of instructions here. I wish it were otherwise, believe me — this game deserves to be played — but I thought it best to warn you right here. It breaks my heart to say this, but if you aren’t ready to roll up your sleeves, this may be one to just watch on YouTube.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The book Designers & Dragons: The 80s by Sheldon Appelcline. Next Generation of November 1996 and November 1998; Computer Gaming World of January 1989, December 1989, November 1990, February 1991, June 1992, July 1995, August 1996, June 1997, July 1997, July 1998, and January 1999; Space Gamer of July/August 1983; Dragon of March 1988. Online sources include Online Gaming Review‘s interview with Internet ’76 producer Scott Krager, an “overview” and “history” of MechWarrior 2 at Local Ditch Gaming, early MechWarrior 2 programmer Eric Peterson’s beginning of a history of his work on the game, Polygon‘s interview with Jordan Weisman and L. Ross Babcock, and the Interstate ’76 wiki. Also Sarna.net’s surveys of The Crescent Hawk’s Inception, MechWarrior 1, the first would be MechWarrior 2, the finished MechWarrior 2, the MechWarrior 2 soundtrack, and the Mercenaries expansion for MechWarrior 2.