Only a few publishers managed to build a reputation to rival that of Epyx as masters of Commodore 64 graphics and sound. Foremost amongst this select group by 1987 was Accolade, riding high on hits like Dam Busters and Ace of Aces. Both of those games were created by Canadian developers Artech, who in 1987 would deliver to Accolade two more of their appealing “aesthetic simulations” of history. Chosen this time were the glory days of NASA for Apollo 18 and of the French Resistance for The Train. Yet Accolade’s big hit of the year would come not from Artech but from another group of Canadians who called themselves Distinctive Software.

Don Mattrick and Jeff Sember, the founders of Distinctive, were barely into their twenties in 1987, but were already has-beens in a sense, veterans of the peculiar form of celebrity the home-computer boom had briefly engendered for a lucky few. The two first met in their high school in late 1981 in the Vancouver suburb of Burnaby, bonding quickly over the Apple II computers that both had at home. During their summer break, Mattrick suggested to Sember that they should design their own game and try to sell it. Thus, while Mattrick worked at a local computer store to raise money for the endeavor, Sember wrote a simple little collection of action games called Evolution in all of three weeks. Its theme was an oddly popular one in 1980s gaming, a chronicle of the evolution of life through six rather arbitrary phases: amoeba, tadpole, rodent, beaver (a tribute to the duo’s home country), gorilla, and human. They took the game to the Vancouver-based Sydney Development Corporation, a finger-in-every-pie would-be mainstay of Canadian computing whom we’ve met before in connection with Artech. Sydney liked Evolution enough to buy it, giving it its public debut in October of 1982 at a Vancouver trade show. With this software thing taking off so nicely, Mattrick and Sember soon incorporated themselves under the name Distinctive Software.

They had arrived on the scene at the perfect zeitgeist moment, just as Canada was waking up to the supposed home-computer revolution burgeoning to its south and was beginning to ask where Canadians were to be found amongst all the excitement. These two young Vancouverites, personable, good-looking, and, according at least to Sydney, the first Canadians ever to write a popular computer game that was sold in the United States as well as its home country, were the perfect answer. They became modest media celebrities over the months that followed, working their way up from the human-interest sections of newspapers to glossy lifestyle magazines and finally to television, where they appeared before a panel of tedious old fuddy-duddies on CBC television’s game-show/journalism hybrid Front Page Challenge. The comparisons here come easily, perhaps almost too easily when we think back to the other software partnerships I’ve already chronicled. It’s particularly hard not to think of David Braben and Ian Bell, who would soon be receiving mainstream coverage of much the same character in Britain. Mattrick was the Braben of this pair, personable, ambitious, and focused on the bottom line; it was he who had gotten the ball rolling in the first place and who would largely continue to drive their business. Sember was the Bell, two years younger, quieter, more technically proficient, and more idealistic about games as a creative medium.

It’s not clear to what extent all of the hype around Mattrick and Sember translated into sales of Evolution. On the one hand, it apparently did well enough on the Apple II for Sydney to fund ports to a number of other platforms and to advertise them fairly heavily across Canada and the United States. And most of the big trade magazines, prompted to some extent no doubt by Sydney’s advertising dollars, saw it as a big enough deal to be worthy of a review. On the other hand, most of those reviews were fairly lukewarm. Typical of them was Electronic Games‘s conclusion that it was okay, but “not really one of the world’s great games.” Nor is it all that well-remembered — whether fondly or otherwise — amongst gaming nostalgics today.

Regardless, after the hype died down Sydney ran into huge problems as the home-computer market in general took a dive. Looking to simplify things and reduce their overhead in response, they elected to get out of the notoriously volatile games-publishing business. Thus the follow-up to Evolution, promised by Mattrick and Sember in many an interview during 1983, never arrived. Their fifteen minutes now apparently passed, it seemed that they would become just one more amongst many historical footnotes to the abortive home-computer revolution.

But then in 1985 Distinctive unexpectedly resurfaced. Alan Miller and Bob Whitehead, having recently founded Accolade, released their own first in-house-developed games, and begun a fruitful developer/publisher partnership with Artech, were looking for more outside developers. They were very receptive to the idea of continuing to work with Canadian developers, believing that they had begun to tap into a well of talent heretofore ignored by the other big publishers. Not the least of their considerations was the Canadian dollar, which was now reaching historic lows in comparison to the American; this meant that that talent came very cheap. When Distinctive’s old connections with Sydney and by extension Artech brought them to Accolade’s attention, they soon had a contract as well.

That said, in the beginning Distinctive was clearly the second-string team in comparison to the more established Artech, hired not to make original games but rather to port Accolade’s established catalog to new platforms. But after some months of doing good work in that capacity, Mattrick, whose sales skills had been evident even in that first summer job working at the computer store — his first boss once declared that he could “sell a refrigerator to an Eskimo” — convinced Miller and Whitehead to let his company tackle an original project of their own.

Over the course of a long career still to come in games, Mattrick would earn himself a reputation as a very mainstream sort of fellow, a fan of the proven bet who would be one of the architects of Electronic Arts’s transformation following Trip Hawkins’s departure in 1991 from a literal band of “electronic artists” to the risk-averse corporate behemoth we know today. Seen in that light, this first game for Accolade, as ambitious as it is boldly innovative, seems doubly anomalous. Given what I know of the two, I suspect that it represents more of Sember’s design sensibility than Mattrick’s, although both are co-credited as its designers and I have no hard facts to back up my suspicion. The game in question is called simply Comics — or, to make it sound a bit less generic, Accolade’s Comics. It is, the box proclaims, the “first living comic book.” “First” anything is often a problematic claim, particularly when it appears in promotional copy, but in this case the claim was justified. While a few earlier games like the licensed Dan Dare: Pilot of the Future had dabbled in a comic-book-style presentation, none had tried to actually be an interactive comic book like this one.

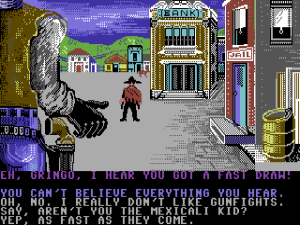

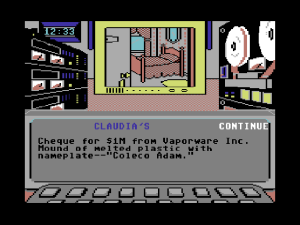

Accolade’s Comics. Notice the arrow sticking out of Steve Keene in the top left panel (“I got your message…”). If you think that’s so stupid it’s funny, you’ll probably enjoy this game. If you think it’s just stupid, probably not. In the same spirit: your boss runs a “Pet Alterations” shop, which is the reason for the poster of the fish with legs at top right.

At its heart, then, Comics is a choice-based narrative which is presented not in text but in comic form, an under- if not completely unexplored approach even today. You make choices every few panels for Steve Keene, a likable but not entirely competent secret-agent sort of fellow who trots the globe on the trail of a kidnapped cable-television inventor or reproducing fire hydrants — no, this isn’t a very serious game. Every once in a while the story will dump you into a little action game which you must get through successfully — you have five lives in total, which you expend by failing at the action games or making choices that result in death — to continue. Like the rest of Comics, these are fun but not too taxing. The look was retro even in its time, drawn to evoke Archie Comics during their 1960s heyday; the price of 20 cents on the virtual front cover that opens the story is a dead giveaway. There’s even a gag based on those perennial old back-of-the-comic-book advertisements for remedies for bullies kicking sand in one’s face and making off with one’s girl. Indeed, there are lots and lots of gags here, most really stupid but in a really clever sort of way. Mileages are notoriously variable when it comes to humor, but personally I find it thoroughly charming.

It’s very difficult to convey the real spirit of the game through words or even through still screenshots, so here’s a movie clip that shows it off to better effect. Old Steve Keene looks a bit like an orangutan in the beginning because I’ve just completed an action game that had him swinging across bars above a pool of water containing something best described as a sharktopus (don’t ask!).

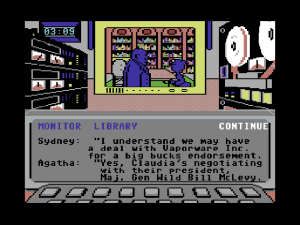

There are a couple of things I’d like you to pay attention to in the clip above, starting with the high production values of the thing (by which I mean the game, sadly not the clip). Note that the music plays while the disk drive loads the next panel, a tricky feat that you simply wouldn’t have seen in an earlier Commodore 64 game. Note how the art, despite the low resolution and the limitation of 16 colors, manages to ooze personality; you’ll never mistake this game for any other. Note the aesthetic professionalism of the whole, as seen in the way each new panel is drawn in with a transition effect rather than just popping into place, the page-flipping animation that introduces a new chapter of the story in lieu of a jarringly abrupt screen-blanking, and the way the music themes also fade out and in during transitions rather than cutting out abruptly.

And then there’s another great gag in the sequence above, one of my favorites in the game. The portrayal of the all too typical American abroad displays a lot more cultural knowingness than one might expect from a couple of sheltered Canadian kids barely out of their teens — as does, for that matter, the decision to reach back so far into comics heritage for inspiration. Comics is filled with dumb jokes, but they don’t really feel like dumb teenage jokes. As someone who’s been exposed to all too much in-game teenage humor in researching this blog over the past years, that may just be the best compliment I can give it.

By the standards of a Commodore 64 game, Comics is an absolutely massive production, spilling across six disk sides and containing almost 400 unique panel illustrations (many with spot animations), a couple of dozen different musical themes, and eight arcade games that each had to be coded from scratch. The team that made it was correspondingly huge for the times, including five artists, a composer, and four programmers in addition to Sember — quite a logistical and financial achievement for a still tiny company run by a 22- and a 20-year-old. For all that, though, Comics hardly feels epic when you play it. It is by design a casual trifle to be enjoyed over the course of just a couple of evenings — one for each of its two completely separate stories that branch off from the very first decision point in the game. That’s fair enough from the perspective of today, but, not for the first time, it was almost untenable in light of the way that commercial software was actually distributed in the 1980s. Upon its release in February of 1987, reviewers noted that Comics had lots of charm, but also noted, reasonably enough, that its price of $35 or more was awfully steep for a couple of evenings’ light entertainment. Many adventure-game purists, not always the most tolerant bunch, complained as well about the action games and the casual nature of the whole endeavor. Shay Addams of the respected Questbusters newsletter, for instance, pronounced that what it really needed was fewer action games and “more puzzles,” proof of the way that genres were already beginning to calcify to a rather depressing degree. Comics had been built with a view to turning it into a series, but, especially in light of how expensive it had been to make, it proved to be a commercial disappointment and thus a one-off in a market that just didn’t quite have a place for it. It nevertheless remains one of my favorite forgotten Commodore 64 gems, and, despite all of its silliness, an interesting experiment in interactive narrative in its own right.

With Comics having failed to set the world alight, the indefatigable Don Mattrick buckled down to try to deliver to Accolade a guaranteed, can’t-miss hit that would establish the Distinctive brand once and for all. At the same time, he began the process of easing Sember out of the company; the latter’s name begins to disappear from Distinctive’s credits at this time, and Mattrick would soon buy him out entirely to take complete control. For his part, Sember would continue to work independently for more than a decade with Accolade as a designer and programmer, most notably of their long-running Hardball series of baseball simulations, before dropping out of the industry around the millennium. As for Mattrick, his first game as a solo designer would be a blueprint for his long future career, evolutionary rather than revolutionary, extrapolating on known trends rather than leaping into the blue. While perhaps not as interesting to revisit via emulator today as its predecessor, it would prove to be much more important in the context of the commercial history of the games industry and, indeed, of Distinctive and Mattrick’s own futures. It would be called Test Drive.

Commercially calculated as it was, Test Drive was also an oddly personal game for Mattrick, very much inspired by his own obsessions. It becomes almost uncomfortably clear on the first page of the manual that you’re living his own personal fantasy: “Your lifelong quest has been to drive one of the world’s most exotic sports cars. Now’s your chance. You just made your first million going public with your software company.”

Don Mattrick has always loved fast cars. One can practically chart the progress of his career merely by looking to what he had in his garage during any given year. He used his first royalty check from Evolution for the down payment on a Toyota Supra; the scenario of Test Drive, of driving as quickly as possible up a twisty mountain road whilst avoiding or outrunning the fuzz, was inspired by his own early adventures therein. By 1987 Distinctive’s success as an Accolade porting house had enabled him to step up to a Porsche 944. But already, as Test Drive‘s manual attests, he was dreaming of an IPO and of leaving his poor man’s Porsche behind to get behind the wheel of a real supercar. I hope I’m not spoiling the story if I reveal that he would indeed soon have a Ferrari in his garage. Decades later, when he was head of Microsoft’s Xbox division and thus one of the most powerful and well-compensated people in gaming, he would reportedly have a ten-car garage stuffed with exotic European metal. If Test Drive represents the dream of every young man, Mattrick would be one of the few to get to actually live it.

Yes, the genius of Test Drive — or, if you like, the luck of the thing — was that Don Mattrick’s personal fantasy was also an almost universal one of young men all over the world. In retrospect, perhaps the most surprising thing about it is that no one had done it before. Driving games of various stripes had been a staple of the arcades for years; Outrun, for instance, arguably the biggest arcade hit of the year prior to Test Drive, had prominently featured a Ferrari Testarossa. Yet virtually no one had created even an alleged simulation of driving, a state of affairs that seems doubly odd when one considers how crazily popular aircraft simulations were, with two of them of 1980s vintage, SubLogic’s Flight Simulator and MicroProse’s F-15 Strike Eagle, eventually exceeding one-million copies in sales in an era when such numbers were all but unimaginable. A car simulation was low-hanging fruit by comparison. As Mattrick himself once said, “A car still has more controls than you’ll find on a joystick, but the components of movement and your choices are fewer.” And yet it just never seemed to occur to anyone to make one.

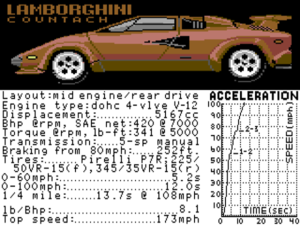

Test Drive would correct that oversight, resoundingly and for all time. At the same time, however, Mattrick and his small team at Distinctive lavished at least as much attention on the lifestyle fantasy as they did on the mechanics of the game. Each of the five featured supercars — the Porsche 911 Turbo, Ferrari Testarossa, Lotus Esprit Turbo, Lamborghini Countach, and Chevrolet Corvette — gets its own loving literal and statistical portrait like the one above, while the dash and interior layouts in the game proper also change to reflect the model you’ve chosen to drive. Test Drive is pure, unabashed car porn. As such, it was tremendously appealing to the demographic that tended to buy computer games.

Still, some reviewers couldn’t help but notice that there just wasn’t really that much to the game. Despite the aspirations to simulationism, it’s hard not to notice that, say, the heavy Corvette with its big, torquey American iron in the front doesn’t drive quite as differently as one might expect from the lighter, notoriously spin-prone Porsche 911 with its buzzy little high-revving engine in the rear. In fact, all of the cars handle rather disconcertingly like they’re on rails, until they suddenly derail and you fall off the side of the mountain. And then there’s the fact that there’s just not that much to really do in Test Drive; you just get to drive up the same mountain over and over again, avoiding the same cops and presumably trying to improve your personal time, with no multiplayer options and no other challenges to add interest. And yet for hundreds of thousands of car-mad kids it just didn’t matter. Test Drive in its day was peculiarly immune to such practical complaints, proof just as much as the works of Cinemaware of just how much the experiential side of a game — the fantasy — can trump the nuts and bolts of gameplay.

Previewed at that same 1987 Summer Consumer Electronics Show to which we’ve been paying so much attention lately and released in plenty of time for Christmas, Test Drive became a hit. More than a hit, it spawned a franchise that is still at least ostensibly alive to this day (the last game to bear the title was released in 2012). More than a franchise, it became the urtext of an entire genre, the automotive-simulation equivalent to Adventure. After going public, buying that first Ferrari, and making his own personal Test Drive fantasy come true, Mattrick sold out to Electronic Arts in 1991, where he morphed Test Drive, whose intellectual property he had left behind with Accolade, into the even more successful Need for Speed series, another franchise that seems destined to continue eternally. At the core of Need for Speed and the several showrooms’ worth of contenders and pretenders that have joined it over the years is that same lifestyle fantasy that Test Drive first tapped into, of having access to a garage full of really sexy cars to inspect and drool over and drive really, really fast. As long as there are young and not-so-young people whose dreams are redolent of well-weathered leather, hot metal and oil, and sunlight on chrome, their continuing popularity seems assured.

(Sources: Questbusters of June 1987; Retro Gamer 59; Computer Gaming World of March 1987, June/July 1987, and February 1988; Compute!’s Gazette of October 1983 and March 1989; Electronic Games of December 1983; Kilobaud of June 1983; The Montreal Gazette of December 15 1982. See also The Escapist’s online article on Mattrick and Distinctive.

Most of the copies of Comics floating around the Internet have one or more muddy disk images. I’ve assembled a set that seems to be 100 percent correct; you’re welcome to download it. It still makes for a very unique and enjoyable experience if you can see fit to install a Commodore 64 emulator to run it. Test Drive, on the other hand, is probably best left to history. Given that, and given that it’s an entry in a still-active franchise, I’m going to leave you on your own to find that one if you want it.)