Fair warning: although there’s no nudity in the pictures below, the text of this article does contain frank descriptions of the human anatomy and sexual acts.

If I’m showing people what a CD-ROM can do, and I try to show them the Kennedy assassination, their eyes glaze over. But if I show them an adult title, they perk right up.

— John Williams of Sierra On-Line, 1995

As long as humans have had technology, they’ve been using it for titillation. A quarter of a million years ago, they were carving female figurines with exaggerated breasts, buttocks, and vulvae out of stone. Well before they started using fired clay to make pottery for the storage of food, they were using the same material to make better versions of these “Venus figurines,” some of them so explicit that the archaeology textbooks of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries didn’t dare to reproduce or even describe them. And then as soon as humans had pigments and dyes to hand, they used them to paint dirty pictures on the walls of their caves.

Immediately after the world’s first known system of writing came to be in Mesopotamia, the people of that region began using it for naughty stories. (In one of them, a new wife tells her husband to place his hand in her “goodly place,” promising to compensate him in kind thereafter: “Let me caress you. My precious caress is more savory than honey.”) The ancient Greeks covered their household and decorative items with sexual imagery. And the Romans too were enthusiastic and uninhibited pornographers, as evidenced by the famous erotic wall frescoes inside Pompeii’s brothel.

Things changed somewhat in Europe with the rise of Christianity, a religion which, unlike the pagan belief systems that preceded it, framed the questions surrounding sex — whether you did it, with whom you did it, how you did it, even how and how much you thought about doing it — as issues of intense spiritual significance. “To be carnally minded is death,” wrote Saint Paul.

Yet the vicarious desires of the flesh couldn’t be quelled even by the prospect of an afterlife of eternal torment. Porn simply went underground, where it has remained to a large extent to this day. The Decameron of Boccaccio and The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, two of the most celebrated examples of Medieval literature, preserve some of the bawdy tales of promiscuous priests and nubile nuns that the largely illiterate peasantry told one another when they gathered in taverns out of earshot of their social betters.

The Gutenberg Bible of the fifteenth century was followed closely by less rarefied printed books, with titles like The Errant Prostitute. In the seventeenth century, the renowned English diarist Samuel Pepys wrote ashamedly of how he had found a copy of a book called The Girls’ School in a second-hand store, and spent so much time perusing its pages whilst, er, indulging himself that he finally felt compelled to burn “that idle, roguish book.” The book generally considered the first true English novel, Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, appeared in 1740; John Cleland’s Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, the first English erotic novel, was published just eight years later. It spawned a lively market for written erotica, the consumption of which, followed perhaps by a visit to a brothel or two, became the Victorian Age’s version of sex education for gentlemen.

And then along came photography. Some of the first photographs ever taken were of nude women and cavorting couples; traveling circuses sold them from under the table to furtive men while their wives and children were off buying sweetmeats. Improved photographic techniques, combined with cheap “pulp” paper and cheaper printing technologies led to the first mass-market “skin” magazine in 1931: The Nudist, a publication of the American Sunbathing Association, who knew perfectly well that most of their audience wasn’t buying the magazine for tips on how best to soak up the rays. Throughout modern times, pornographers have often couched titillation under just such a veneer of “educational value.” And another, even more enduring truth of modern porn was also on display in The Nudist‘s pages: the camera lens focused most lovingly on the women. The producers and consumers of visual pornography have always been mostly men, although the reasons why this has been the case are matters for debate among psychologists, anthropologists, and sociologists. (The opposite is largely the case for textual erotica in the post-photographic age, for whatever that’s worth.)

By the time The Nudist made the scene, still images of nakedness already had serious competition. Back in 1896, Thomas Edison had released a movie called The Kiss to widespread outrage. “They get ready to kiss, begin to kiss, and kiss and kiss and kiss in a way that brings down the house every time,” ran the description in Edison’s catalog, rather overselling the thrill of an 18-second movie that ends with little more than a chaste series of henpecks. But never fear, matters quickly escalated from there. The first known full-fledged porn film appeared in 1908. A synopsis of the action shows that, when it comes to porn as so many other things, those wise words from the Book of Ecclesiastes (“The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done; and there is no new thing under the sun”) ring true: “A woman was seen pleasuring herself with a dildo, then another man and woman joined her for a threesome, involving lots of oral sex before intercourse.” By the 1920s, a full-fledged “blue” film industry was thriving in Hollywood alongside the more respectable one, using many of the same sets and in some cases even the same performers. The arrival of the Hays Code in 1933 put a damper on some of the fun, but the blue movies never went away, just slunk further underground. During the Second World War, the American military turned a blind eye to the “stag films” that infiltrated its ranks at every level; those who made them said it was their patriotic duty to help the boys in uniform through all those lonely nights in the barracks.

The sexual revolution of the 1960s brought big changes to movies, both above- and below-ground. Suddenly things that hadn’t been seen in respectable fare since 1933 — bare female breasts and sex scenes prominent among them — became commonplace in even the most conservative Middle American movie houses. At the same time, the arrival of cheap Super 8 cameras and projectors combined with the general loosening of social mores to yield what some connoisseurs still call the “golden age” of porn. To distinguish themselves from a less prudish mainstream-film industry, the purveyors of porn pushed boundaries of their own, into every imaginable combination of people and occasionally animals, with ever tighter shots of the actual equipment in action, as it were.

By 1970, there were more than 750 porn-only movie theaters in the United States alone. In 1973, a pornographic comedy called Deep Throat, a timeless tale of a woman born with her clitoris on the wrong end of her torso, became an international sensation, shown even by many “legitimate” theaters. Made for $25,000, it eventually grossed $100 million, enough to make it far and away the most successful film of all time when measured in terms of return on investment.

At the time, Deep Throat was widely heralded as the future of porn, but the era of mainstream “porno chic” which it ushered in proved short-lived. Instead of yielding more blockbusters in the style of respectable Hollywood, the porn industry that came after was distinguished by the sheer quantity of material it rolled out for every taste and kink. This explosion was enabled by the arrival of videotape in 1975; shooting direct to video was cheaper by almost an order of magnitude than even Super 8 film. But even more importantly, videotape players for the home gave the porn hounds and would-be porn hounds of the world a way to consume movies in privacy, thereby giving the porn industry access to millions upon millions of upstanding pillars of their communities who would never have frequented sticky-seated cinemas. Every porno kingpin in the world redoubled his production efforts in response, even as they all rushed en masse to move their libraries of “classics” onto videotape as well. The gold rush that followed made Deep Throat look like the flash in the pan it was. In 1978 and 1979, three quarters of all home movies sold in the United States were porn. That percentage inevitably dropped as the technology went more mainstream in the 1980s, but the raw numbers remained huge. Even in the late 1990s, Americans were still renting $4.2 billion worth of porn on videotape each year.

Advances in voice communication as well were co-opted by porn. The party lines of the 1960s and the pay-per-call services that sprang up in the 1980s were quickly taken over by it: respectively, by people wanting to talk dirty to one another and by people willing to pay a professional to talk dirty to them.

Just why is porn so perpetually on the technological cutting edge, both driving and being driven by each new invention that comes around? Perhaps it’s down to its fundamentally aspirational nature. While voyeurism for the sake of it certainly has a place on the list of human fetishes, for most of its consumers porn is a substitute — by definition a less than ideal one — for something they’re not getting, whether just in that precise moment or in their current life in general. So, they’re always looking for ways to get closer to the real thing, as Walter Kendrick, the author of a book-length history of porn, told The New York Times back in 1994.

Pornography is always unsatisfied. It’s always a substitute for the contact between two bodies, so there’s a drive behind it that doesn’t exist in other genres. Pornographers have been the most inventive and resourceful users of whatever medium comes along because they and their audience have always wanted innovations. Pornographers are excluded from the mainstream channels, so they look around for something new, and the audience has a desire to try any innovation that gives them greater realism or immediacy.

If you look at the history of pornography and new technologies, the track record has been pretty good. Usually everyone has come out ahead. The pornography people have gotten what they want, which is a more vivid way to portray sex. And the technology has benefited from their experimentation. The need for innovation in pornography is so great that it usually gets to a medium first and finds out what can be done and what can’t.

If early computers are not as strong an example of this phenomenon as photography, film, and videotape, that perhaps speaks more to the nature and limitations of that particular technology than it does to any lack of abstract interest in using computers for getting off. Yet sex definitely wasn’t absent from the picture even here. I’ve written elsewhere on this site of how the men who worked at Bell Labs in the 1960s contrived ways to put naked women on their monitor screens using grids of alphanumeric characters in lieu of a proper bitmap, of how Scott Adams sold games of Strip Dice alongside his iconic early adventure games, and of how Sierra On-Line once made a mint with the naughty text adventure Softporn, about a loser who wishes he was a swinger trying to navigate the dating scene of the late disco era.

Softporn may have had a name that no big publisher like Sierra would have dared use much after its 1981 release date, but in other ways it became the template for the mainstream games industry’s handling of sex. The rule was that a little bit of sexiness was okay if it was presented in the context of comedy. Infocom’s Leather Goddesses of Phobos went this way to significant success in 1986, helping to convince Sierra to revisit the basic premise of Softporn in the graphical adventure Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards the following year. Larry starred in a whole series of games after his first one proved a huge hit, becoming the poster child for risqué computer gaming. His success in turn brought more games of a similar style from other publishers, from Accolade’s Les Manley (yes, really) series to Legend’s Spellcasting series. The players of such games walked a fine line between being vicariously titillated alongside their protagonists and laughing at them for being the losers they were.

Still, even the Church Lady would have blanched at calling such games porn; they were in fact no more explicit than the typical PG-13-rated frat-boy movie. To find pictures of actual naked women on computers, you would have to download them — slowly! — from a BBS, or buy a still less respectable game like Artwox’s Strip Poker via mail order.[1]A few years ago, I went to a retro-gaming exhibition here in Denmark with a friend of mine. We got to talking with a woman who worked at the museum hosting it, who told us of her own memories from those times. It seems her brother had managed to acquire a copy of Strip Poker for his Commodore Amiga. Being a lover of card games, she tried to play it, but all the stupid pictures kept getting in the way. “I just wanted to play poker!” she lamented. I suspect this story may have something to tell us about the differences between the genders, but I have no idea what it is. Few distributors or retailers would risk handling such titles, what with the mainstream culture’s general impression that any and all forms of digital entertainment were inherently kids’ stuff.

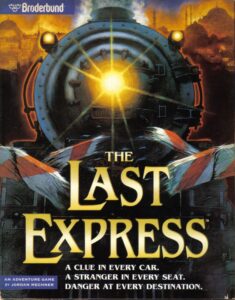

But by 1993 or so, that impression was at last beginning to change. The arrival of mouse-driven user interfaces, decent graphics and sound, and CD-ROM had made “multimedia” one of the buzzwords of the zeitgeist. Part and parcel of the multimedia boom was a new generation of “interactive movies,” which featured real human actors playing their roles according to your instructions. Computer games, went the conventional wisdom, were growing up to become sophisticated adult entertainment — potentially in all senses of the word “adult.” Just like the makers of conventional movies during the 1960s, the makers of these interactive movies were eager to push the boundaries, to explore previously taboo subjects and see how much they could get away with. They had to be careful; 1993 was also the year of an overheated Senate hearing on videogame content, partially prompted by an early interactive movie for the Sega Genesis console called Night Trap. But be that as it may, many of the people behind interactive movies believed strongly in the principle that they should be allowed to show anything that a non-porn traditional film might, as long as, like such a film, they played with an open hand, disclosing the nature of the content to possible buyers upfront.

The pioneer of the risqué — but not pornographic — interactive movie was a game called Voyeur, released in 1993 for the Philips CD-i, a multimedia set-top box for the living room — don’t call it a games console! — that was marketed primarily to adults. The following year, Voyeur made it to ordinary computers as well.

Masterminded by David Riordan, whose earlier attempt at an interactive movie It Came from the Desert has aged much better, Voyeur casts you as a private dick surveilling a potential candidate for the American presidency, a fellow who makes Gary Hart and Bill Clinton look like choirboys. Everything from infidelity to incest, from sado-masochism to an eventual murder is going on in his house. But, like so many productions of this ilk, the game is caught between the urge to titillate and the fear of going too far and getting itself blacklisted. The end result is a weird mixture of the provocative and the prudish, as inimitably described by Charles Ardai, the most entertaining reviewer ever to write for Computer Gaming World magazine.

For those connoisseurs of striptease who prefer the tease to the strip, Voyeur should be a source of endless delight. Women are forever unfastening their bra straps in this game, or opening their towels while conveniently facing away from the camera, or walking around in unbuttoned vests that don’t quite reveal what you think they’re going to, or leaning toward each other for lesbian kisses that somehow never get completed. Men have it worse in some ways: they get led around in bondage collars, handcuffed to bedposts, and violently groped by their sisters. No one actually manages to have sex, though; all they do is go around interrupting each other. No wonder that after several hours of this someone ends up murdered.

Coming a year after a panties-less Sharon Stone had shocked movie-goers in that scene in Basic Instinct, in a time when even network television shows like NYPD Blue were beginning to flirt with nudity, Voyeur was pretty tame stuff, notable only for existing on a computer. There was very little actual game to Voyeur, even by comparison to most interactive movies; as the player, your choices were limited to deciding which window to peep into at any given time. Yet it attracted a storm of press coverage and sold very well by the standards of the time — enough to prompt a belated 1996 sequel that was if anything even more problematic as a game and that didn’t sell anywhere near as well.

In fact, only one other game of this stripe can be called an outright commercial success. That game was Sierra’s 1995 release Phantasmagoria, designed against type by Roberta Williams, best known as the creator of the family-friendly King’s Quest series. Having written about it at some length in another article, I won’t repeat myself here. Suffice to say that Phantasmagoria became Sierra’s best-selling game to date, despite or because of content that was not quite as transgressive as the game’s advertising made it appear. In his memoir, Sierra’s co-founder (and Roberta’s husband) Ken Williams speaks of the curious dance — two steps forward, one step back — that interactive movies like this one were constantly engaged in.

There was a scene in Phantasmagoria which was shot with Victoria Morsell, the heroine of the story, topless. Roberta wrote the scene and helped direct it. If it were a horror film no one would have thought anything about it, other than giving the film an “R” rating. But this was a videogame, and the market hadn’t fully realized yet that interactive stories weren’t always just for kids. When it came time to release the game, we edited [it] to only show some side-boob. Even with only a hint of nudity, Phantasmagoria was not a game we felt was appropriate for children. [We] voluntarily self-rated the product with a large “M” for Mature.

But Ken Williams must have believed the market was evolving quickly, because just a year after the first Phantasmagoria Sierra released a sequel in name only — it had nothing to do with the characters or story of the first — called Phantasmagoria: A Puzzle of Flesh, which proudly strutted all of the stuff that its predecessor had only hinted at. Designed by Lorelei Shannon rather than Roberta Williams, A Puzzle of Flesh was as sexually explicit as any mainstream game would get during the 1990s, an interactive exploitation flick steeped in sado-masochism, bondage, and the bare boobies that had been so conspicuously lacking from Roberta’s game. Like too many Sierra adventure games, its writing and design both left something to be desired. And yet it was an important experiment in its way, demonstrating to everyone who might have been contemplating making a game like it that there really were boundaries which they would be well advised not to cross. In contrast to many organs of game journalism, Computer Gaming World did deign to give A Puzzle of Flesh a review, but said review oozes disgust: “Playing this game, if one can grace this morally reprehensible product with such happy terms as ‘play’ and ‘game,’ is extremely unpleasant; to do so ‘for fun’ requires a fascination with hardcore schlock or a hardened attitude toward horror and exploitive erotica. You have been duly warned.”

It speaks to one of the peculiarities of American culture that the magazine could work itself into such a lather of moral outrage over this game whilst praising the booby-less ultra-violence of HyperBlade (“The 3D Battlesport of the Future!”) in the very same issue. (“Fractured skull. Severed bronchial artery. Shattered tibia. This will eventually come as music to your ears. Want to cut an opponent’s head off and throw it in the goal? Pretty brazen, but that’s okay too.”) But such were the conditions on the ground, and publishers had to learn to live with them. Sierra never made another full-fledged interactive movie after A Puzzle of Flesh. The genre as a whole slowly died as the limitations of games made from spliced-together pieces of canned video became clear to even the most casual players. The dream of a games industry that regularly delivered R-rated content in terms of sex as well as violence blew away like so much chaff on the breeze alongside the rest of the interactive-movie fad. Mind you, games would continue to be full of big-breasted, scantily-clad women to feed the male gaze, but gamers wouldn’t get to see them in action in the bedroom.

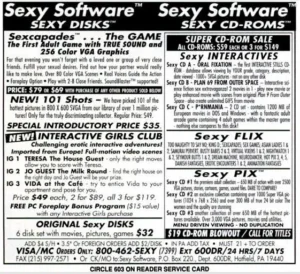

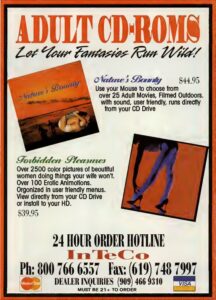

Yet this isn’t to say that there was no sex whatsoever to be had on CD-ROM. Far from it. Even as the above-ground industry’s fad for interactive movies was swelling up and then petering out, there was plenty of explicit sex available for consumption on “seedy ROM,” the name a wag writing for The New York Times coined for the underground genre. A cottage industry sprang up around the technology of CD-ROM when it was still in its infancy — an industry which it would be disarmingly easy for a historian like me, trolling through my old issues of Computer Gaming World and the like, to never realize ever existed. This has always been the way with porn; despite its eternal popularity, it lives in the shadows, segregated from other forms of media whose consumers are less ashamed of their habit. It is forced to exist in its own parallel universe of distribution and sales — and yet people who are determined to see it always find a way to meet it where it lives. This was as true of porn during the multimedia-computing boom as it has been in every other technological era and context.

The pioneer of the seedy-ROM field, coming already in 1990 — fully three years before Voyeur, at a time when the standards around CD-ROM had barely been set and most people had not yet even heard of it — was a product of a tiny company called Reactor, Incorporated. It called itself Virtual Valerie. Implemented using Apple’s HyperCard authoring system, it plays a bit like The Manhole with sex; you can explore your girlfriend Valerie’s apartment, discovering a surprising number of secret paths and Easter eggs therein, or you can spend your time exploring Valerie herself. Relying on hand-drawn pixel graphics rather than digitized photographs or video, it’s whimsical in personality — almost innocent by contrast with what would come later — but it nevertheless demonstrated that there was an eager market for this sort of thing. “A left-handed mouse designed for use by right-handed people will be a hot seller,” wrote Anne Gregor only partly jokingly in CD-ROM Today, one of the few glossy magazines that dared to cover this space at all.

Virtual Valerie was the canary in the coal mine. In her wake, dozens of companies plunged into making and selling porn on CD-ROM, smelling an opportunity akin to the porn-on-videotape boom of the recent past. They sold disks full of murky images downloaded from Usenet, where a lively trade in porn went on alongside lively discussions. They sold old porn movies on CDs, the better for gentlemen to view on the computer in the home office, away from the prying eyes of the wife and kids. (The Voyager Company’s version of the Beatles film A Hard Day’s Night was promoted in 1993 as the very first full-length movie on CD-ROM, but it actually wasn’t this at all: it was rather the first non-pornographic movie on CD-ROM.) And then there were the more ambitious, genuinely interactive efforts that followed in the footsteps of Virtual Valerie. “Virtual girlfriends” became a veritable sub-genre unto itself for a while. Girlfriend Teri, for example, claimed a vocabulary of 3000 words. Journalist Nancie S. Martin called her perfect for men who preferred “a woman you can talk to, who, unlike most real women, has no opinions of her own. While she can’t discuss Proust, she can say, ‘It’s so big!’ on demand.”

It was proof of a longstanding axiom in media: no matter how daunting the obstacles to distribution, porn will out. When American CD-duplication houses refused their business, the purveyors of seedy ROMs found alternatives in Canada. When no existing software distributor or retailer was willing to touch their products, when the big computer and gaming magazines too rejected them or allowed them only small advertisements sequestered in their back pages, they advertised in the skin magazines and urban newspapers instead, and sealed the deal through mail order and through porn-rental shops that stocked their CDs alongside the usual videotapes. Those who joined this latest porn gold rush were a variegated lot, ranging from the likes of Playboy and Penthouse, whose libraries of photographs stretched back decades, to hardcore pornography pimpers like Vivid Media with catalogs of their own that were equally ripe for re-purposing, to fresh faces who were excited about the overall potential of multimedia, and saw porn as a way to make money from it or to nudge it along as a consumer-facing technology, or both.

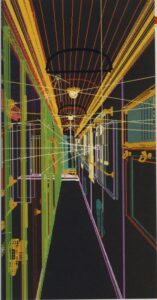

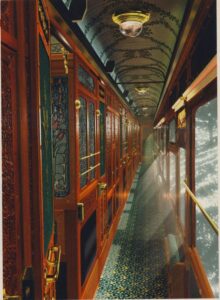

One of these newcomers to porn was New Machine Publishing, founded by one Larry Miller and two other 25-year-old men in 1992. “At first, we thought we’d do a CD-ROM on the rain forest,” Miller told The Los Angeles Times three years later. “It was gonna be interactive, have bird calls, native music, all that stuff. Then we discovered we were not thinking in real-world terms. No one would have bought it.” Instead they acquired a bunch of footage from a local porno-production company and stuck it on a CD alongside a frame story not that far away in spirit from Voyeur: you were a guest at a hotel where all the rooms were wired for video and sound, and you were in the catbird seat in the control room. The difference, of course, was that their “interactive porn movie,” which they called Nightwatch, didn’t shirk from the money shots. They took 500 Nightwatch discs to a Macworld show in San Francisco and sold every single one of them, at $70 a pop. Attendees “would cruise by,” remembered Miller. “Then they would get to the end of the aisle and do a U-turn.”

It turned out that porn was immune to the infelicities of this early era of digital video that caused customers to turn away from more upstanding multimedia productions. While few could convince themselves to overlook the fact that Voyager’s A Hard Day’s Night played in a resolution more suited to a postage stamp than a computer monitor, they were happy to peer at Nightwatch‘s even blearier clips, jittering before them enigmatically at all of five frames per second. New Machine plowed their Nightwatch profits into The Interactive Adventures of Seymore Butts (yes, really), which did for Leisure Suit Larry what their previous seedy ROM had done for Voyeur. Everyone knew the drill of this sort of scenario by now: another loser protagonist out on the town trying to score. Except that Seymore would get lucky in a way that Larry or Les and their players could hardly have begun to imagine.

Indeed, New Machine was now able to pay for their own film shoots. Robert A. Jones of The Los Angeles Times was permitted to visit the set one day, and returned to bear witness to the ultimate hollowness of mechanistic sex without emotion or context: “Watching it unfold, it’s hard to believe anything of redeeming value could be salvaged from this scene of bored sordidness.” There has always been money to be made in some people’s compulsion to keep watching porn long after the novelty is gone. Why should seedy ROMs be any different?

But, you might be asking, how much money are we talking about here? Alas, that’s a tough question to answer with any degree of certainty. Because porn lives underground, both abhorring the light of mainstream attention and being likewise abhorred, it has always been notoriously difficult to figure out how much money people are actually making from the stuff. Porn on CD-ROM is no exception. That said, the sheer quantity of it that was out there by the middle of the 1990s indicates that real money was being made by at least some of its providers. To be sure, no one was selling discs in the quantities of Voyeur or Phantasmagoria. But then again, they didn’t have to, thanks to vastly cheaper production budgets and the ability to charge a premium price. This latter has always been one of the advantages of peddling smut: most people just want to take their porn and disappear back into blessed anonymity, not haggle and bargain hunt.

We do have some data points. The founders of New Machine Publishing alluded vaguely to selling “tens of thousands” of copies of Seymore Butts, more than many a more wholesome point-and-click adventure game of the era. The first Penthouse Virtual Photo Shoot disc — “Be the photographer!” — reportedly sold 30,000 copies in its first three months. (In another testament to its popularity, no fewer than five additional volumes, featuring different sets of girls for the camera’s roving eye to capture, were later released.) Vivid Entertainment’s interactive division reported having four 10,000-plus sellers on CD-ROM already in the spring of 1994, barely six months after its founding. Fay Sharp, who acted as a distributor and liaison between seedy-ROM makers and mom-and-pop porn shops all over the country, claimed that $260 million worth of porn on disc was sold in that same year. Pixis Interactive claimed multiple titles with sales of 50,000 to 100,000 units a couple of years after that. For all that such numbers may still have been a drop in the bucket compared to porn on videotape, they could mean serious money for the people involved, with the tantalizing prospect of a lot more where that had come from in the future, once multimedia personal computers had become as ubiquitous in American homes as videocassette players. In short, and despite the fact that seedy ROMs would never blow up quite as spectacularly as many of the folks involved in them expected — we’ll get to the reasons for that shortly — all signs are that some people in this market did very well for themselves for a while, thanks to sales that in many cases seem to have dwarfed the numbers racked up by, say, The Voyager Company’s lineup of high-brow explorations of history and science.

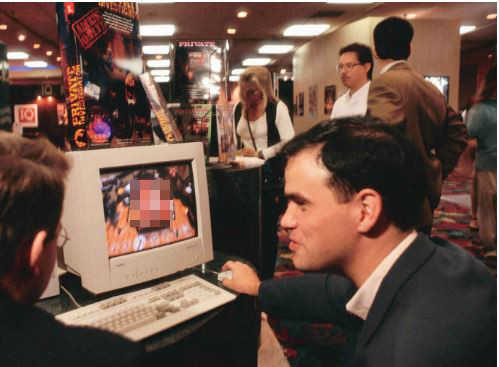

Perhaps the best testimony to the real if brief-lived success of porn on CD-ROM is a brouhaha that erupted at COMDEX, the buttoned-down computer industry’s biggest trade show, taking place in November of each year in Las Vegas. In 1993, The New York Times reported with considerable surprise that porn had become one of the highlights of the show in the opinion of businessmen who were ostensibly there to investigate decidedly unsexy server racks and backup systems and the like.

“CD-ROM brings unimaginable quantities of knowledge to those for whom information is their most valuable asset,” said Bill Kelly, president of PC Compo Net of La Habra, California, who sells such knowledge bases as L.A. Strippers: Bikes & Babes & Rock ‘n’ Roll. PC Compo Net was among a half dozen companies selling CD-ROM titles that depict graphic sex with video, sound, and still images. The displays caused traffic jams in the aisles as the predominantly male computer crowd stopped to gawk. Many customers waved fists of cash. One harried booth clerk noted that CD-ROM is ideal for circumventing Japanese laws restricting pornographic films and magazines, because the mirror-like disks give no clue as to their contents and can easily be slipped through customs in an audio-CD case.

Some COMDEX exhibitors complained about their X-rated neighbors on moral grounds; others said they were pleased by the crowds. One Japanese computer dealer, who asked that his name not be used, said it appears that pornography may be the long-awaited “killer” application that will spur the sale of CD-ROM drives. “People who develop CD-ROM software should be overjoyed that we’re here, because we’re helping sell CD-ROM drives,” said Lawrence Miller, one of three partners in New Machine Publishing of Santa Monica, California, which makes games with explicit sexual content.

Concerned about their show’s image, the COMDEX organizers moved the seedy-ROM exhibits into a dank corner of the basement the following year — an apt metaphor for pornography’s place in polite society, yes, but one the exhibitors themselves considered less than gracious, given that they were by now contributing about half a million dollars to the show’s bottom line. In return, COMDEX couldn’t even be bothered to keep the power on for them all the time down there in the cellar. Its organizers were deaf to their complaints: “COMDEX is a place where people show creative new products for the benefit of the industry. This is not appropriate.”

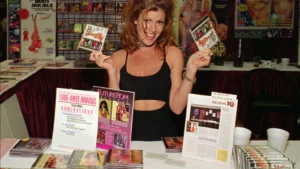

So, Fay Sharp, a rare woman in porn in a role other than that of performer, set up her own show in 1995 just a few blocks away from that year’s COMDEX. Called AdultDex, its admission charge was just $20 if you could show a COMDEX ticket. “COMDEX is the classroom and AdultDex is recess,” said William Margold of the Free Speech Coalition, one of the new show’s sponsors. About 7500 people came by that first year, while the bigger show’s organizers huffed and hawed and threatened this unwelcome parasite. In the end, though, there was nothing they could do about it.

AdultDex became a regular event thereafter, drawing upwards of 20,000 attendees some years. The scene there was much the same as that in the countless Vegas strip clubs that catered to the same clientele of business road warriors enjoying a taste of freedom from the strictures of family life. (“COMDEX attendees don’t gamble, but they line up in those gentlemen’s clubs,” said the chairwoman of the tourism and convention department at the University of Nevada. “I’ve been on flights coming into Las Vegas sitting next to hookers who fly in just for that week.”) Journalist Samantha Cole describes AdultDex as “men in polo shirts and cheap brown suits standing too close to tanned women in bikinis and leather, or leaning their five-o’clock shadows on their breasts. One thing that’s never changed through decades of Las Vegas porn conferences: in this gin-scented setting, men and women do seem like separate species.”

In 1997, the police raided AdultDex — at the instigation, many suspected, of the COMDEX organizers — and handed out citations for “lewd and dissolute conduct” and “performing a live sex act.” But, as always, the porn show must go on. “We were on CNN, the local TV; we have even had an editorial in the newspaper that was favorable,” said Fay Sharp to Billboard magazine. “It’s giving us the kind of publicity we could never buy. It’s showing [that] adult interactivity is very much in the mainstream.” AdultDex wouldn’t pass into history until 2003, when it expired, like any good parasite, alongside its host, COMDEX itself.

Yet even as Fay Sharp was saying those words in 1997, the nature of the products being peddled at AdultDex was changing markedly. The fact was that the seedy-ROM boom was already past its peak, already starting onto the down slope toward what all those dirty discs have become today: the kitschy detritus of a quaint past, media artifacts which manifestly failed to reach the world-changing heights once predicted for them. Pixis Interactive reported that year that its latest sales figures looked suddenly “ghastly.” The smart folks in the cottage industry were now plotting exit strategies from CD-ROM, which in some cases involved going legit — or at least more legit — in one way or another. The boys behind New Machine, for example, reinvested their Seymore Butts profits into casino games on CD-ROM, then took that concept online. At the turn of the millennium, their virtualvegas.com was one of the most popular online-gaming sites on the Internet.

Meanwhile those digital impresarios who intended to stay in porn were trying to figure out how to execute a dramatic shift in terms of delivery medium. For, just as video had once killed the radio star, the World Wide Web was now all too clearly killing the multimedia CD-ROM, regardless of whether it concerned itself with kinky sex or with the fate of the rain forests. Seedy ROMs wouldn’t disappear because of any shortage of horny boys and men — perish the thought! They would disappear because anything they could do, the Web could do better — cheaper and easier and, best of all, even more anonymously. The fact was that the Web was about to change humanity’s relationship to sex in general to an extent that few of even the most enthusiastic proponents of sex on CD-ROM would have ventured to predict. And, almost equally interestingly, sex was about to change the Web — change not only the sites people surfed to and what they did there, but make the whole place safe for commerce and its filthy lucre in a way that a million wide-eyed idealists like its original inventor Tim Berners-Lee could never have managed.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: the books How Sex Changed the Internet and the Internet Changed Sex by Samantha Cole, Obscene Profits: The Entrepreneurs of Pornography in the Cyber Age by Frederick S. Lane III, The Players Ball: A Genius, a Con Man, and the Secret History of the Internet’s Rise by David Kushner, The Erotic Engine by Patchen Barss, The Pornography Wars: The Past, Present, and Future of America’s Obscene Obsession by Kelsy Burke, and Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings by Ken Williams; The New York Times of November 21 1993, January 9 1994, and October 4 1995; CD-ROM Today of June/July 1994; Electronic Entertainment of August 1994 and August 1995; Wired of July 1995; Computer Gaming World of March 1995, July 1996, and March 1997; Wired of July 1995 and February 1997; The Los Angeles Times of March 19 1995; The San Francisco Chronicle of November 19 1997; frieze of March/April 1996; The Las Vegas Sun of November 19 1996; American Heritage of September/October 2000. Online sources include “Inside AdultDex” by Adi Robertson at The Verge, “COMDEX Trade Show Leaves Vegas” by Chris Jones at Casino City Times, and “History of Sex in Cinema” at filmsite.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | A few years ago, I went to a retro-gaming exhibition here in Denmark with a friend of mine. We got to talking with a woman who worked at the museum hosting it, who told us of her own memories from those times. It seems her brother had managed to acquire a copy of Strip Poker for his Commodore Amiga. Being a lover of card games, she tried to play it, but all the stupid pictures kept getting in the way. “I just wanted to play poker!” she lamented. I suspect this story may have something to tell us about the differences between the genders, but I have no idea what it is. |

|---|