The first and most iconic of all the Choose Your Own Adventure books involved spelunking, just as did the first and most iconic of all computer-based adventure games.

These books were the gateway drugs of interactive entertainment.

— Choose Your Own Adventure historian Christian Swineheart

My first experience with interactive media wasn’t mediated by any sort of digital technology. Instead it came courtesy of a “technology” that was already more than half a millennium old at the time: the printed book.

In the fall of 1980, I was eight years old, and doing my childish best to adjust to life in a suburb of Dallas, Texas, where my family had moved the previous summer from the vicinity of Youngstown, Ohio. I was a skinny, frail kid who wasn’t very good at throwing balls or throwing punches, which did nothing to ease the transition. Even when I wasn’t being actively picked on, I was bewildered at my new classmates’ turns of phrase (“I reckon,” “y’all,” “I’m fixin’ to”) that I had previously heard only in the John Wayne movies I watched on my dad’s knee. In their eyes, my birthplace north of the Mason Dixon Line meant that I could be dismissed as just another clueless, borderline useless “Yankee,” a heathen in the eyes of those who adhered to my new state’s twin religions of Baptist Christianity and Friday-night football.

I found my refuge in my imagination. I was interested in just about everything — a trait I’ve never lost, both to my benefit and my detriment in life — and I could sit for long periods of time in my room, spinning out fantasies in my head about school lessons, about books I’d read, about television shows I’d seen, even about songs I’d heard on the radio. I actually framed this as a distinct activity in my mind: “I’m going to go imagine now.” If nothing else, it was good training for becoming a writer. As they say, the child is the father of the man.

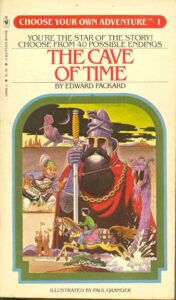

One Friday afternoon, I discovered a slim, well-thumbed volume in my elementary school’s scanty library. Above the title The Cave of Time was the now-iconic Choose Your Own Adventure masthead, proclaiming it to be the first book in a series. Curious as always, I opened it to the first page. I was precocious enough to know what was meant by a first-person and third-person narrator of written fiction, but this was something else: this book was written in the second person.

You’ve hiked through Snake Canyon once before while visiting your Uncle Howard at Red Creek Ranch, but you never noticed any cave entrance. It looks as though a recent rock slide has uncovered it.

Though the late afternoon sun is striking the surface of the cave, the interior remains in total darkness. You step inside a few feet, trying to get an idea of how big it is. As your eyes become used to the dark, you see what looks like a tunnel ahead, dimly lit by some kind of phosphorescent material on its walls. The tunnel walls are smooth, as if they were shaped by running water. After twenty feet or so, the tunnel curves. You wonder where it leads. You venture in a bit further, but you feel nervous being alone in such a strange place. You turn and hurry out.

A thunderstorm may be coming, judging by how dark it looks outside. Suddenly you realize the sun has long since set, and the landscape is lit only by the pale light of the full moon. You must have fallen asleep and woken up hours later. But then you remember something even more strange. Just last evening, the moon was only a slim crescent in the sky.

You wonder how long you’ve been in the cave. You are not hungry. You don’t feel you have been sleeping. You wonder whether to try to walk back home by moonlight or whether to wait for dawn, rather than risk your footing on the steep and rocky trail.

All of this was intriguing enough already for a kid like me, but now came the kicker. The book asked me — asked me!! — whether I wanted to “start back home” (“turn to page 4”) or to “wait” (“turn to page 5”). This was the book I had never known I needed, a vehicle for the imagination like no other.

I took The Cave of Time home and devoured it that weekend. Through the simple expedient of flipping through its pages, I time-traveled to the age of dinosaurs, to the Battle of Gettysburg, to London during the Blitz, to the building of the Great Wall of China, to the Titanic and the Ice Age and the Middle Ages. Much of this history was entirely new to me, igniting whole new avenues of interest. Today, it’s all too easy to see all of the limitations and infelicities of The Cave of Time and its successors: a book of 115 pages that had, as it proudly trumpeted on the cover, 40 possible endings meant that the sum total of any given adventure wasn’t likely to span more than about three choices if you were lucky. But to a lonely, hyper-imaginative eight-year-old, none of that mattered. I was well and truly smitten, not so much by what the book was as by what I wished it to be, by what I was able to turn it into in my mind by the sheer intensity of that wish.

I remained a devoted Choose Your Own Adventure reader for the next couple of years. Back in those days, each book could be had for just $1.25, well within reach of a young boy’s allowance even at a time when a dollar was worth a lot more than it is today. Each volume had some archetypal-feeling adventurous theme that made it catnip for a kid who was also discovering Jules Verne and beginning to flirt with golden-age science fiction (the golden age being, of course, age twelve): deep-sea diving, a journey by hot-air balloon, the Wild West, a cross-country auto race, the Egyptian pyramids, a hunt for the Abominable Snowman. What they evoked in me was as important as what was actually printed on the page; each was a springboard for another weekend of fantasizing about exotic undertakings where nobody mocked you because you had two left feet in gym class and spoke with a stubbornly persistent Northern accent. And each was a springboard for learning as well; this process usually started with pestering my parents, and then, if I didn’t get everything I needed from that source, ended with me turning to the family set of Encyclopedia Britannica in the study. (I remember how when reading Journey Under the Sea I was confused by frequent references to “the bends.” I asked my mom what that meant, and, bless her heart, she said she thought the bends were diarrhea. Needless to say, this put a whole new spin on my underwater exploits until I finally did a bit of my own research about diving.)

Inevitably, I did begin to see the limitations of the format in time — right about the time that some of my nerdier classmates, whom I had by now managed to connect with, started to show me a tabletop game called Dungeons & Dragons. Choose Your Own Adventure had primed me to understand and respond to it right away; it would be no exaggeration to say that I saw this game that would remake so much of the entertainment landscape in its image as simply a better, less constrained take on the same core concept. Ditto the computer games that I began to notice in a corner of the bookstore I haunted circa 1984. When Infocom promised me that playing one of their games meant “waking up inside a story,” I knew exactly what they must mean: Choose Your Own Adventure done right. For the Christmas of 1984, I convinced my parents to buy me a disk drive for the Commodore 64 they had bought me the year before. And so the die was cast. If Choose Your Own Adventure hadn’t come along, I don’t think that I would be the Digital Antiquarian today.

But since I am the Digital Antiquarian, I have my usual array of questions to ask. Where did Choose Your Own Adventure, that gateway drug for the first generation to be raised on interactive media, come from? Who was responsible for it? The most obvious answer is the authors Edward Packard and R.A. Montgomery, one or the other of whose name could be seen on most of the early books in the series. But two authors alone do not a cultural phenomenon make.

“Will you read me a story?”

“Read you a story? What fun would that be? I’ve got a better idea: let’s tell a story together.”

— Adam Cadre, Photopia

During the twentieth century, when print still ruled the roost, the hidden hands behind the American cultural zeitgeist were the agents, editors, and marketers in and around the big Manhattan publishing houses, who decided which books were worth publishing and promoting, who decided what they would look like and even to a large extent how they would read. No one outside of the insular world of print publishing knew these people’s names, but the power they had to shape hearts and minds was enormous — arguably more so than that of any of the writers they served. After all, even the most prolific author of fiction or non-fiction usually couldn’t turn out more than one book per year, whereas an agent or editor could quietly, anonymously leave her fingerprints on dozens. Amy Berkower, a name I’m pretty sure you’ve never heard of, is a fine case in point.

Berkower joined Writers House, one of the most prestigious of the New York literary agencies, during the mid-1970s as a “secretarial girl.” Having shown herself to be an enthusiastic go-getter by working long hours and sitting in on countless meetings, she was promoted to the role of agent in 1977, but assigned to “juvenile publishing,” largely because nobody else in the organization wanted to work with such non-prestigious books. Yet the assignment suited Berkower just fine. “As a kid, I read and loved Nancy Drew before I went on to Camus,” she says. “I was in the right place at the right time. I didn’t have the bias that juvenile series wouldn’t lead to Camus.”

Thus when a fellow named Ray Montgomery came to her with a unique concept he called Adventures of You, he found a receptive audience. Montgomery was the co-owner of a small press called Vermont Crossroads, far removed from the glitz and glamor of Manhattan. Crossroads’s typical fare was esoteric volumes like Hemingway in Michigan and The Male Nude in Photography that generally weren’t expected to break four digits in total unit sales. A few years earlier, however, Montgomery had himself been approached by Edward Packard, a lawyer by trade who had already pitched a multiple-choice children’s book called Sugarcane Island to what felt like every other publisher in the country without success.

As he would find himself relating again and again to curious journalists in the decades to come, Packard had come up with his idea for an interactive book by making a virtue of necessity. During the 1960s, he was an up-and-coming attorney who worked long days in Manhattan, to which he commuted by train from his and his wife’s home in Greenwich, Connecticut. He often arrived home in the evening just in time to put his two daughters to bed. They liked to be told a bedtime story, but Packard was usually so exhausted that he had trouble coming up with one. So, he slyly enlisted his daughters’ help with the creative process. He would feed them a little bit of a story in which they were the stars, then ask them what they wanted to do next. Their answers would jog his tired imagination, and he would be off and running once again.

Sometimes, though, the girls would each want to do something different. “What would happen if you wrote both endings?” Packard mused to himself. A long-time frustrated writer as well as a self-described “lawyer who was never comfortable with the law,” Packard began to wonder whether he could turn his interactive bedtime stories into a new kind of book. By as early as 1969, he had invented the classic Choose Your Own Adventure format — turn to this page to do this, turn to that page to do that — and produced his first finished work in the style: the aforementioned Sugarcane Island, about a youngster who gets swept off the deck of a scientific research vessel by a sudden tidal wave and washed ashore on a mysterious Pacific island that has monsters, pirates, sharks, headhunters, and many another staple of more traditional children’s adventure fiction to contend with.

He was sure that it was “such a wonderful idea, I’d immediately find a big publisher.” He signed on with an agent, who “said he would be surprised if there were no takers,” recalls Packard. “Then he proceeded to be surprised.” One rejection letter stated that “it’s hard enough to get children to read, and you’re just making it harder with all these choices.” Letters like that came over and over again, over a period of years.

By 1975, Edward Packard was divorced from both his agent and his wife. With his daughters no longer of an age to beg for bedtime stories, he had just about resigned himself to being a lawyer forever. Then, whilst flipping through an issue of Vermont Life during a stay at a ski lodge, he happened upon a small advertisement from Crossroads Press. “Authors Wanted,” it read. Crossroads wasn’t the bright-lights, big-city publisher Packard had once dreamed of, but on a lark he sent a copy of Sugarcane Island to the address in the magazine.

It arrived on the desk of Ray Montgomery, who was instantly intrigued. “I Xeroxed 50 copies of Ed’s manuscript and took it to a reading teacher in Stowe,” Montgomery told The New York Times in 1981. “His kids — third grade through junior high — couldn’t get enough of it.” Satisfied by that proof of concept, Montgomery agreed to publish the book. Crossroads Press sold 8000 copies of Sugarcane Island over the next couple of years, a figure that was “unbelievable” by their modest standards. Montgomery was inspired to pen a book of his own in the same style, which he called Journey Under the Sea. The budding series was given the name Adventures of You — a proof that, whatever else they may have had going for them, branding was not really Crossroads Press’s strength.

Indeed, Montgomery himself was well able to see that he had stumbled over a concept that was too big for his little press. He sent the two extant books to Amy Berkower at Writers House and asked her what she thought. Having grown up on Nancy Drew, she was inclined to judge them less on their individual merits than on their prospects as a franchise in the making. A concept this new, she judged, had to have a strong brand of its own in order for children to get used to it. It would take her some time to find a publisher who agreed with her.

In the meantime, Edward Packard, heartened by the relative success of Sugarcane Island, was writing more interactive books. Although their names were destined to be indelibly linked in the annals of pop-culture history, Packard and Montgomery would never really be friends; they would always have a somewhat prickly, contentious relationship with one another. In an early signal of this, Packard chose not to publish more books through Crossroads. Instead he convinced the mid-list Philadelphia-based publisher J.B. Lippincott to take on Deadwood City, a Western, and Third Planet from Altair, a sci-fi tale. These served ironically to confirm Amy Berkower’s belief that there needed to be a concerted push behind the concept as a branded series; released with no fanfare whatsoever, neither sold all that well. Yet Lippincott did do Packard one brilliant service. Above the titles on the covers of the books, it placed the words “Choose your own adventures in the Wild West!” and “Choose your own adventures in outer space!” There was a brand in the offing in those phrases, even if Lippincott didn’t realize it.

For her part, Berkower was now more convinced than ever that this book-by-book approach was the wrong one. There needed to be a lot of these books, quickly, in order for them to take off properly. She made the rounds of the big publishing houses one more time. She finally found the ally she was looking for in Joëlle Delbourgo at Bantam Books. Delbourgo recalls getting “really excited” by the concept: “I said, ‘Amy, this is revolutionary.’ This is pre-computer, remember. The idea of interactive fiction, choosing an ending, was fresh and novel. It tapped into something very fundamental. I remember how I felt when I read the books, and how excited I got, the clarity I had about them.”

Seeing eye to eye on what needed to be done to cement the concept in the minds of the nation’s children, the two women drew up a contract under whose terms Bantam would publish an initial order of no fewer than six books in two slates of three. They would appear under a distinctive series trade dress, with each volume numbered to feed young readers’ collecting instinct. Barbara Marcus, Bantam’s marketing director for children’s books, needed only slightly modify the phrases deployed by J.B. Lippincott to create the perfect, pithy, and as-yet un-trademarked name for the series: Choose Your Own Adventure.

Berkower was acting as the agent of Montgomery alone up to this point. There are conflicting reports as to how and why Packard was brought into the fold. The widow of Ray Montgomery, who died in 2014, told The New Yorker in 2022 that her husband’s innate sense of fair play, plus the need to provide a lot of books quickly, prompted him to voluntarily bring Packard on as an equal partner. Edward Packard told the same magazine that it was Bantam who insisted that he be included, possibly in order to head off potential legal problems in the future.

At any rate, the first three Choose Your Own Adventure paperbacks arrived in bookstores in July of 1979. They were The Cave of Time, a new effort by Packard, written with some assistance from his daughter Andrea, she for whom he had first begun to tell his interactive stories; Montgomery’s journeyman Journey Under the Sea; and By Balloon to the Sahara, which Packard and Montgomery had subcontracted out to Douglas Terman, normally an author of adult military thrillers. Faced with an advertising budget that was almost nonexistent, Barbara Marcus devised an unusual grass-roots marketing strategy: “We did absolutely nothing except give the books away. We gave thousands of books to our salesmen and told them to give five to each bookseller and tell him to give them to the first five kids into his shop.”

The series sold itself, just as Marcus had believed it would. As The New York Times would soon write with a mixture of bemusement and condescension, it proved “contagious as chickenpox.” By September of 1980, around the time that I first discovered The Cave of Time, Publishers Weekly could report that Choose Your Own Adventure had become a “bonanza” for Bantam, which had sold more than 1 million copies of the first six volumes, with Packard and Montgomery now contracted to provide many more. A year later, eleven books in all had come out and the total sold was 4 million, with the series accounting for eight of the 25 bestselling children’s books at B. Dalton’s, the nation’s largest bookstore chain. A year after that, 10 million copies had been sold. By decade’s end, the total domestic sales of Choose Your Own Adventure would reach 34 million copies, with possibly that many or more again having been sold internationally after being translated into dozens of languages. The series was approaching its hundredth numbered volume by that point. It was a few years past its commercial peak already, but would continue on for another decade, until 184 volumes in all had come out.

Edward Packard, who turned 50 in 1981, could finally call himself an author rather than a lawyer by trade — and an astonishingly successful author at that, if not one who was likely to be given any awards by the literary elite. He and Ray Montgomery alone wrote about half of the 184 Choose Your Own Adventure installments. Packard’s prose was consistently solid and evocative without ever feeling like he was writing down to his audience, as the extract from The Cave of Time near the beginning of this article will attest; not all authors of children’s books, then or now, would dare to use a word like “phosphorescent.” If Montgomery was generally a less skilled wordsmith than Packard, and one who displayed less interest in producing internally consistent story spaces — weaknesses that I could see even as a young boy — he does deserve a full measure of credit for the pains he took to get the series off the ground in the first place. Looking back on the long struggle to get his brainstorm into print, Packard liked to quote the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer: “Every original idea is first ridiculed, then vigorously attacked, and finally taken for granted.”

Although Packard at least was always careful to make his protagonists androgynous, it was no secret that Choose Your Own Adventure appealed primarily to boys — which was no bad thing on the whole, given that it was also no secret that reading in general was a harder sell with little boys than it was with little girls. Some educators and child psychologists kvetched about the violence that was undoubtedly one of the sources of the series’s appeal for boys — in just about all of the books, it was disarmingly easy to get yourself flamboyantly and creatively killed — but Packard was quick to counter that the mayhem was all very stylized, “exaggerated and melodramatic” rather than “harsh or nasty.” “Stupid” choices were presented to you all the time, he noted, but never “cruel” ones: “You as [the] reader never hurt anyone.”

Although Packard always strained to present an “AFGNCAAP” protagonist (“Ageless, Faceless, Gender-Neutral, Culturally Ambiguous Adventure Person”), when the stars of the books were depicted on the covers they were almost always boys. Bantam explained to a disgruntled Packard that it had many years of market research showing that, while little girls were willing to buy books that showed a hero of the opposite gender on the cover, little boys were not similarly open-minded.

One had to be a publishing insider to know that this “boys series” owed its enormous success as much to the packaging and promotional skills of three women — Amy Berkower, Joëlle Delbourgo, and Barbara Marcus — as it did to the literary talents of Packard and Montgomery. Berkower in particular became a superstar within the publishing world in the wake of Choose Your Own Adventure. Incredibly, the latter became only her second most successful children’s franchise, after the girl-focused Sweet Valley High, which could boast of 54 million copies sold domestically by the end of the 1980s; meanwhile The Baby-Sitters Club was coming up fast behind Choose Your Own Adventure, with 27 million copies sold. In short, her books were reaching millions upon millions of children every single month. Small wonder that she was made a full partner at Writers House in 1988; she was moving far more books each month than anyone else there.

Of course, any hit on the scale of Choose Your Own Adventure is bound to be copied. And this hit most certainly was, prolifically and unashamedly. During the middle years of the 1980s, when the format was at its peak, interactive books had whole aisles dedicated to them in bookstores. Which Way?, Decide Your Own Adventure, Pick-a-Path, Twisted Tales… branders did what they could when the best brand was already taken. While Choose Your Own Adventure remained archetypal in its themes and settings, other lines were unabashedly idiosyncratic: anyone up for a Do-It-Yourself Jewish Adventure? Publishers were quick to leverage other properties for which they owned the rights, from Doctor Who to The Lord of the Rings. TSR, the maker of that other school-cafeteria sensation Dungeons & Dragons, introduced an interactive-book line drawn from the game; even this website’s old friend Infocom came out with Zork books, written by the star computer-game implementor Steve Meretzky. Many of these books were content with the Choose Your Own Adventure approach of nothing but chunks of text tied to arbitrarily branching choices, but others grafted rules systems onto the format to effectively become solo role-playing games packaged as paperback books, with character creation and advancement, a dice-driven combat system, etc. The most successful of these lines was Fighting Fantasy, a name that is today almost as well-remembered as Choose Your Own Adventure itself in some quarters.

The gamebook boom was big and real, but relatively short-lived. By 1987, the decline had begun, for both Choose Your Own Adventure and all of the copycats and expansions upon its formula that it had spawned. Although a few of the most lucrative series, like Fighting Fantasy, would join the ur-property of the genre in surviving well into the 1990s, the majority were already starting to shrivel and fall away like apples in November. Demian Katz, the Internet’s foremost archivist of gamebooks, notes that this pattern has tended to hold true “in every country” where they make an appearance: “A few come out, they become explosively popular, a flood of knock-offs are released, they reach critical mass and then drop off into nothing.” It isn’t hard to spot the reason why in the context of 1980s North America. Computers were becoming steadily more commonplace — computers that were capable of bringing vastly more flexible forms of interactive storytelling to American children, via games that didn’t require one to read the same passages of text over and over again or to toss dice and keep track of a list of statistics on paper. The same pattern would be repeated elsewhere, such as in the former Soviet countries, most of which experienced their own gamebook boom and bust during the 1990s. It seems that the arrival of the commercial mass-market publishing infrastructure that makes gamebooks go is generally followed in short order by the arrival of affordable digital technology for the home, which stops them cold.

In the United States, Bantam Books tried throughout the 1990s to make Choose Your Own Adventure feel relevant to the children of that decade, introducing a more photo-realistic art style to accompany edgier, more traditionally novelistic plots. None of it worked. In 1999, after a good twelve years of slowly but steadily declining sales, Bantam finally pulled the plug on the series. Choose Your Own Adventure became just another nostalgic relic of the day-glo decade, to be placed on the shelf next to Michael Jackson’s Thriller, a Jane Fonda workout video, and that old Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set.

Appropriately enough, the very last Choose Your Own Adventure book was written by Edward and Andrea Packard, the latter being the grown-up version of one of the little girls to whom he had once told interactive bedtime stories.

As of this writing, Choose Your Own Adventure is still around in a way, but the only real raison d’être it has left is nostalgia. In 2003, Ray Montgomery saw that Bantam Books had let the trademark for the series lapse, and formed his own company called Chooseco to try to revive it, mostly by republishing the old books that he had written himself. He met with mixed results at best. Since Montgomery’s death in 2014, Chooseco has continued to be operated by his family, who have used it increasingly as an instrument of litigation. In 2020, for example, Netflix agreed to settle for an undisclosed sum a lawsuit over “Bandersnatch,” a bold interactive episode of the critically lauded streaming series Black Mirror whose script unwisely mentioned the book series from which it drew inspiration.

A worthier successor on the whole is Choice Of Games, a name whose similarity to Choose Your Own Adventure can hardly be coincidental. Born out of a revival of the old menu-driven computer game Alter Ego, Choice Of has released dozens of digital branching stories over the past fifteen years. In being more adventurous than literary and basing themselves around broad, archetypal ideas — Choice of the Dragon, Choice of Broadsides, Choice of the Vampire — these games, which can run on just about any digital device capable of putting words on a screen, have done a fine job of carrying the spirit of Choose Your Own Adventure forward into this century. That said, there is one noteworthy difference: they are aimed at post-pubescent teens and adults — perhaps ones with fond memories of Choose Your Own Adventure — instead of children. “Play as male, female, or nonbinary; cis or trans; gay, straight, or bisexual; asexual and/or aromantic; allosexual and/or alloromantic; monogamous or polyamorous!” (Boring middle-aged married guy that I am, I must confess that I have no idea what three of those words even mean.)

Edward Packard, the father of it all, is still with us at age 94, still blogging from time to time, still a little bemused at how he became one of the most successful working authors in the United States during the 1980s. In a plot twist almost as improbable as some of his stranger Choose Your Own Adventure endings, his grandson is David Corenswet, the latest actor to play Superman on the silver screen. Never a computer gamer, Packard would doubtless be baffled by most of what is featured on this website. And yet I owe him an immense debt of gratitude, for giving me my first glimpse of the potential of interactive storytelling, thus igniting a lifelong obsession. I suspect that more than one of you out there might be able to say the same.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: Publishers Weekly of February 29 1980, September 26 1980, October 8 1982, July 25 1986, August 12 1988, December 1 1989, July 6 1990, February 23 1998; New York Times of August 25 1981; Beaver County Times of March 30 1986; New Yorker of September 19 2022; Journal of American Studies of May 2021.

Online sources include “A Brief History of Choose Your Own Adventure“ by Jake Rossen at Mental Floss, “Choose Your Own Adventure: How The Cave of Time Taught Us to Love Interactive Entertainment” by Grady Hendrix at Slate, “The Surprising Long History of Choose Your Own Adventure Stories” by Jackie Mansky at the Smithsonian’s website, and “Meet the 91-Year-Old Mastermind Behind Choose Your Own Adventure“ by Seth Abramovitch at The Hollywood Reporter. Plus Edward Packard’s personal site. And Damian Katz’s exhaustive gamebook site is essential to anyone interested in these subjects; all of the book covers shown in this article were taken from his site.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | A truly incredible figure of 250 million copies sold is frequently cited for the original Choose Your Own Adventure series today, apparently on the basis of a statement released in January of 2007 by Choosco, a company which has repeatedly attempted to reboot the series in the post-millennial era. Based upon the running tally of sales which appeared in Publishers Weekly during the books’ 1980s heyday, I struggle to see how this figure can be correct. That journal of record reported 34 million Choose Your Own Adventure books sold in North America as of December 1, 1989. By that time, the series’s best years as a commercial proposition were already behind it. Even when factoring in international sales, which were definitely considerable, it is difficult to see how the total figure could have exceeded 100 million books sold at the outside. Having said that, however, the fact remains that the series sold an awful lot of books by any standard. |

|---|