On August 6, 1991, when Microsoft was still in the earliest planning stages of creating the operating system that would become known as Windows 95, an obscure British researcher named Tim Berners-Lee, working out of the Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire (CERN) in Switzerland, put the world’s first publicly accessible website online. For years to come, these two projects would continue to evolve separately, blissfully unconcerned by if not unaware of one another’s existence. And indeed, it is difficult to imagine two computing projects with more opposite personalities. Mirroring its co-founder and CEO Bill Gates, Microsoft was intensely pragmatic and maniacally competitive. Tim Berners-Lee, on the other hand, was a classic academic, a theorist and idealist rather than a businessman. The computers on which he and his ilk built the early Web ran esoteric operating systems like NeXTSTEP and Unix, or at their most plebeian MacOS, not Microsoft’s mass-market workhorse Windows. Microsoft gave you tools for getting everyday things done, while the World Wide Web spent the first couple of years of its existence as little more than an airy proof of concept, to be evangelized by wide-eyed adherents who often appeared to have read one too many William Gibson novels. Forbes magazine was soon to anoint Bill Gates the world’s richest person, his reward for capturing almost half of the international software market; the nascent Web was nowhere to be found in the likes of Forbes.

Those critics who claim that Microsoft was never a visionary company — that it instead thrived by letting others innovate, then swooping in and taking taking over the markets thus opened — love to point to its history with the World Wide Web as Exhibit Number One. Despite having a role which presumably demanded that he stay familiar with all leading-edge developments in computing, Bill Gates by his own admission never even heard of the Web until April of 1993, twenty months after that first site went up. And he didn’t actually surf the Web for himself until another six months after that — perhaps not coincidentally, shortly after a Windows version of NCSA Mosaic, the user-friendly graphical browser that made the Web a welcoming place even for those whose souls didn’t burn with a passion for information theory, had finally been released.

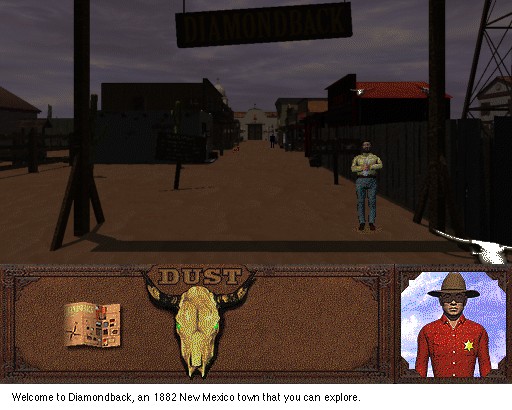

Gates focused instead on a different model of online communication, one arguably more in keeping with his instincts than was the free and open Web. For almost a decade and a half by 1993, various companies had been offering proprietary dial-up services aimed at owners of home computers. These came complete with early incarnations of many of the staples of modern online life: email, chat lines, discussion forums, online shopping, online banking, online gaming, even online dating. They were different from the Web in that they were walled gardens that provided no access to anything that lay beyond the big mainframes that hosted them. Yet within their walls lived bustling communities whose citizens paid their landlords by the minute for the privilege of participation.

The 500-pound gorilla of this market had always been CompuServe, which had been in the business since the days when a state-of-the-art home computer had 16 K of memory and used cassette tapes for storage. Of late, however, an upstart service called America Online (AOL) had been making waves. Under Steve Case, its wunderkind CEO, AOL aimed its pitch straight at the heart of Middle America rather than the tech-savvy elite. Over the course of 1993 alone, it went from 300,000 to 500,000 subscribers. But that was only the beginning if one listened to Case. For a second Home Computer Revolution, destined to be infinitely more successful and long-lasting than the first, was now in full swing, powered along by the ease of use of Windows 3 and by the latest consumer-grade hardware, which made computing faster and more aesthetically attractive than it had ever been before. AOL’s quick and easy custom software fit in perfectly with these trends. Surely this model of the online future — of curated content offered up by a firm whose stated ambition was to be the latest big player in mass media as a whole; of a subscription model that functioned much like the cable television which the large majority of Americans were already paying for — was more likely to take hold than the anarchic jungle that was the World Wide Web. It was, at any rate, a model that Bill Gates could understand very well, and naturally gravitated toward. Never one to leave cash on the table, he started asking himself how Microsoft could get a piece of this action as well.

Steve Case celebrates outside the New York Stock Exchange on March 19, 1992, the day America Online went public.

Gates proceeded in his standard fashion: in May of 1993, he tried to buy AOL outright. But Steve Case, who nursed dreams of becoming a media mogul on the scale of Walt Disney or Jack Warner, turned him down flat. At this juncture, Russ Siegelman, a 33-year-old physicist-by-education whom Gates had made his point man for online strategy, suggested a second classically Microsoft solution to the dilemma: they could build their own online service that copied AOL in most respects, then bury their rival with money and sheer ubiquity. They could, Siegelman suggested, make their own network an integral part of the eventual Windows 95, make signing up for it just another step in the installation process. How could AOL possibly compete with that? It was the first step down a fraught road that would lead to widespread outrage inside the computer industry and one of the most high-stakes anti-trust investigations in the history of American business — but for all that, the broad strategy would prove very, very effective once it reached its final form. It had a ways still to go at this stage, though, targeting as it did AOL instead of the Web.

Gates put Siegelman in charge of building Microsoft’s online service, which was code-named Project Marvel. “We were not thinking about the Internet at all,” admits one of the project’s managers. “Our competition was CompuServe and America Online. That’s what we were focused on, a proprietary online service.” At the time, there were exactly two computers in Microsoft’s sprawling Redmond, Washington, campus that were connected to the Internet. “Most college kids knew much more than we did because they were exposed to it,” says the Marvel manager. “If I had wanted to connect to the Internet, it would have been easier for me to get into my car and drive over to the University of Washington than to try and get on the Internet at Microsoft.”

It came down to the old “not built here” syndrome that dogs so many large institutions, as well as the fact that the Web and the Internet on which it lived were free, and Bill Gates tended to hold that which was free in contempt. Anyone who attempted to help him over his mental block — and there were more than a few of them at Microsoft — was greeted with an all-purpose rejoinder: “How are we going to make money off of free?” The biggest revolution in computing since the arrival of the first pre-assembled personal computers back in 1977 was taking place all around him, and Gates seemed constitutionally incapable of seeing it for what it was.

In the meantime, others were beginning to address the vexing question of how you made money out of free. On April 4, 1994, Marc Andreessen, the impetus behind the NCSA Mosaic browser, joined forces with Jim Clark, a veteran Silicon Valley entrepreneur, to found Netscape Communications for the purpose of making a commercial version of the Mosaic browser. A team of programmers, working without consulting the Mosaic source code so as to avoid legal problems, soon did just that, and uploaded Netscape Navigator to the Web on October 13, 1994. Distributed under the shareware model, with a $39 licensing fee requested but not demanded after a 90-day trial period was up, the new browser was installed on more than 10 million computers within nine months.

AOL’s growth had continued apace despite the concurrent explosion of the open Web; by the time of Netscape Navigator’s release, the service had 1.25 million subscribers. Yet Steve Case, no one’s idea of a hardcore techie, was ironically faster to see the potential — or threat — of the Web than was Bill Gates. He adopted a strategy in response that would make him for a time at least a superhero of the business press and the investor set. Instead of fighting the Web, AOL would embrace it — would offer its own Web browser to go along with its proprietary content, thereby adding a gate to its garden wall and tempting subscribers with the best of both worlds. As always for AOL, the whole package would be pitched toward neophytes, with a friendly interface and lots of safeguards — “training wheels,” as the tech cognoscenti dismissively dubbed them — to keep the unwashed masses safe when they did venture out into the untamed wilds of the Web.

But Case needed a browser of his own in order to execute his strategy, and he needed it in a hurry. He needed, in short, to buy a browser rather than build one. He saw three possibilities. One was to bring Netscape and its Navigator into the AOL fold. Another was a small company called Spyglass, a spinoff of the National Center for Supercomputing (NCSA) which was attempting to commercialize the original NCSA Mosaic browser. And the last was a startup called Booklink Technologies, which was making a browser from scratch.

Netscape was undoubtedly the superstar of the bunch, but that didn’t help AOL’s cause any; Marc Andreessen and Jim Clark weren’t about to sell out to anyone. Spyglass, on the other hand, struck Case as an unimaginative Johnny-come-lately that was trying to shut the barn door long after the horse called Netscape had busted out. That left only Booklink. In November of 1994, AOL paid $30 million for the company. The business press scoffed, deeming it a well-nigh flabbergasting over-payment. But Case would get the last laugh.

While AOL was thus rushing urgently to “embrace and extend” the Web, to choose an ominous phrase normally associated with Microsoft, the latter was dawdling along more lackadaisically toward a reckoning with the Internet. During that same busy fall of 1994, IBM released OS/2 3.0, which was marketed as OS/2 Warp in the hope of lending it some much-needed excitement. By either name, it was the latest iteration of an operating system that IBM had originally developed in partnership with Microsoft, an operating system that had once been regarded by both companies as nothing less than the future of mainstream computing. But since the pair’s final falling out in 1991, OS/2 had become an irrelevancy in the face of the Windows juggernaut, winning a measure of affection only in some hacker circles and a few other specialized niches. Despite its snazzy new name and despite being an impressive piece of software from a purely technical perspective, OS/2 Warp wasn’t widely expected to change those fortunes before its release, and this lack of expectations proved well-founded afterward. Yet it was a landmark in another way, being the first operating system to include a Web browser as an integral component, in this case a program called Web Explorer, created by IBM itself because no one else seemed much interested in making a browser for the unpopular OS/2.

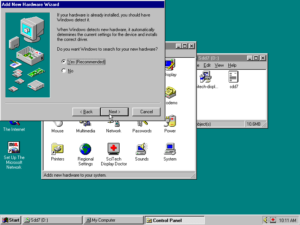

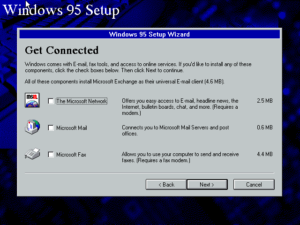

This appears to have gotten some gears turning in Bill Gates’s head. Microsoft already planned to include more networking tools than ever before in Windows 95. They had, for example, finally decided to bow to customer demand and build right into the operating system TCP/IP, the networking protocol that allowed a computer to join the Internet; Windows 3 required the installation of a third-party add-on for the same purpose. (“I don’t know what it is, and I don’t want to know what it is,” said Steve Ballmer, Gates’s right-hand man, to his programmers on the subject of TCP/IP. “[But] my customers are screaming about it. Make the pain go away.”) Maybe a Microsoft-branded Web browser for Windows 95 would be a good idea as well, if they could acquire one without breaking the bank.

Just days after AOL bought Booklink for $30 million, Microsoft agreed to give $2 million to Spyglass. In return, Spyglass would give Microsoft a copy of the Mosaic source code, which it could then use as the basis for its own browser. But, lest you be tempted to see this transaction as evidence that Gates’s opinions about the online future had already undergone a sea change by this date, know that the very day this deal went down was also the one on which he chose to publicly announce Microsoft’s own proprietary AOL competitor, to be known as simply the Microsoft Network, or MSN. At most, Gates saw the open Web at this stage as an adjunct to MSN, just as it would soon become to AOL. MSN would come bundled into Windows 95, he told the assembled press, so that anyone who wished to could become a subscriber at the click of a mouse.

The announcement caused alarm bells to ring at AOL. “The Windows operating system is what the dial tone is to the phone industry,” said Steve Case. He thus became neither the first nor the last of Gates’s rival to hint at the need for government intervention: “There needs to be a level playing field on which companies compete.” Some pundits projected that Microsoft might sign up 20 million subscribers to MSN before 1995 was out. Others — the ones whom time would prove to have been more prescient — shook their heads and wondered how Microsoft could still be so clueless about the revolutionary nature of the World Wide Web.

AOL leveraged the Booklink browser to begin offering its subscribers Web access very early in 1995, whereupon its previously robust rate of growth turned downright torrid. By November of 1995, it would have 4 million subscribers. The personable and photogenic Steve Case became a celebrity in his own right, to the point of starring in a splashy advertising campaign for The Gap’s line of khakis; the man and the pants represented respectively the personification and the uniform of the trend in corporate America toward “business casual.” Meanwhile Case’s company became an indelible part of the 1990s zeitgeist. “You’ve got mail!,” the words AOL’s software spoke every time a new email arrived — something that was still very much a novel experience for many subscribers — was featured as a sample in a Prince song, and eventually became the name of a hugely popular romantic comedy starring Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan. CompuServe and AOL’s other old rivals in the proprietary space tried to compete by setting up Internet gateways of their own, but were never able to negotiate the transition from one era of online life to another with the same aplomb as AOL, and gradually faded into irrelevancy.

Thankfully for Microsoft’s shareholders, Bill Gates’s eyes were opened before his company suffered the same fate. At the eleventh hour, with what were supposed to be the final touches being put onto Windows 95, he made a sharp swerve in strategy. He grasped at last that the open Web was the here, the now, and the future, the first major development in mainstream consumer computing in years that hadn’t been more or less dictated by Microsoft — but be that as it may, the Web wasn’t going anywhere. On May 26, 1995, he wrote a memo to every Microsoft employee that exuded an all-hands-on-deck sense of urgency. Gates, the longstanding Internet agnostic, had well and truly gotten the Internet religion.

I want to make clear that our focus on the Internet is critical to every part of our business. The Internet is the most important single development to come along since the IBM PC was introduced in 1981. It is even more important than the arrival of [the] graphical user interface (GUI). The PC analogy is apt for many reasons. The PC wasn’t perfect. Aspects of the PC were arbitrary or even poor. However, a phenomena [sic] grew up around the IBM PC that made it a key element of everything that would happen for the next fifteen years. Companies that tried to fight the PC standard often had good reasons for doing so, but they failed because the phenomena overcame any weakness that [the] resistors identified.

Over the last year, a number of people [at Microsoft] have championed embracing TCP/IP, hyperlinking, HTML, and building clients, tools, and servers that compete on the Internet. However, we still have a lot to do. I want every product plan to try and go overboard on Internet features.

Everything changed that day. Instead of walling its campus off from the Internet, Microsoft put the Web at every employee’s fingertips. Gates himself sent his people lists of hot new websites to explore and learn from. The team tasked with building the Microsoft browser, who had heretofore labored in under-staffed obscurity, suddenly had all the resources of the company at their beck and call. The fact was, Gates was scared; his fear oozes palpably from the aggressive language of the memo above. (Other people talked of “joining” the Internet; Gates wanted to “compete” on it.)

But just what was he so afraid of? A pair of data points provides us with some clues. Three days before he wrote his memo, a new programming language and run-time environment had taken the industry by storm. And the day after he did so, a Microsoft executive named Ben Slivka sent out a memo of his own with Gate’s blessing, bearing the odd title of “The Web Is the Next Platform.” To understand what Slivka was driving at, and why Bill Gates took it as such an imminent existential threat to his company’s core business model, we need to back up a few years and look at the origins of the aforementioned programming language.

Bill Joy, an old-school hacker who had made fundamental contributions to the Unix operating system, was regarded as something between a guru and an elder statesman by 1990s techies, who liked to call him “the other Bill.” In early 1991, he shared an eye-opening piece of his mind at a formal dinner for select insiders. Microsoft was then on the ascendant, he acknowledged, but they were “cruising for a bruising.” Sticking with the automotive theme, he compared their products to the American-made cars that had dominated until the 1970s — until the Japanese had come along peddling cars of their own that were more efficient, more reliable, and just plain better than the domestic competition. He said that the same fate would probably befall Microsoft within five to seven years, when a wind of change of one sort or another came along to upend the company and its bloated, ugly products. Just four years later, people would be pointing to a piece of technology from his own company Sun Microsystems as the prophesied agent of Microsoft’s undoing.

Sun had been founded in 1982 to leverage the skills of Joy along with those of a German hardware engineer named Andy Bechtolsheim, who had recently built an elegant desktop computer inspired by the legendary Alto machines of Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center. Over the remainder of the 1980s, Sun made a good living as the premier maker of Unix-based workstations: computers that were a bit too expensive to be marketed to even the most well-heeled consumers, but were among the most powerful of their day that could be fit onto or under a single desktop. Sun possessed a healthy antipathy for Microsoft, for all of the usual reasons cited by the hacker contingent: they considered Microsoft’s software derivative and boring, considered the Intel hardware on which it ran equally clunky and kludgy (Sun first employed Motorola chips, then processors of their own design), and loathed Microsoft’s intensely adversarial and proprietorial approach to everything it touched. For some time, however, Sun’s objections remained merely philosophical; occupying opposite ends of the market as they did, the two companies seldom crossed one another’s paths. But by the end of the decade, the latest Intel hardware had advanced enough to be comparable with that being peddled by Sun. And by the time that Bill Joy made his prediction, Sun knew that something called Windows NT was in the works, knew that Microsoft would be coming in earnest for the high-end-computing space very soon.

About six months after Joy played the oracle, Sun’s management agreed to allow one of their star programmers, a fellow named James Gosling, to form a small independent group in order to explore an idea that had little obviously to do with the company’s main business. “When someone as smart as James wants to pursue an area, we’ll do our best to provide an environment,” said Chief Technology Officer Eric Schmidt.

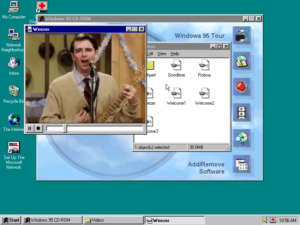

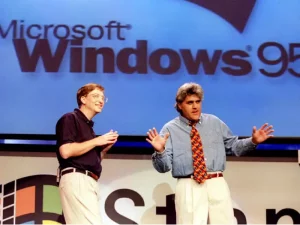

The specific “area” — or, perhaps better said, problem — that Gosling wanted to address was one that still exists to a large extent today: the inscrutability and lack of interoperability of so many of the gadgets that power our daily lives. The problem would be neatly crystalized almost five years later by one of the milquetoast jokes Jay Leno made at the Windows 95 launch, about how the VCR in even Bill Gates’s living room was still blinking “12:00” because he had never figured out how to set the thing’s clock. What if everything in your house could be made to talk together, wondered Gosling, so that setting one clock would set all of them — so that you didn’t have to have a separate remote control for your television and your VCR, each with about 80 buttons on it that you didn’t understand what they did and never, ever pressed. “What does it take to watch a videotape?” he mused. “You go plunk, plunk, plunk on all of these things in certain magic sequences before you can actually watch your videotape! Why is it so hard? Wouldn’t it be nice if you could just slide the tape into the VCR, [and] the system sort of figures it out: ‘Oh, gee, I guess he wants to watch it, so I ought to power up the television set.'”

But when Gosling and his colleagues started to ponder how best to realize their semi-autonomous home of the future, they tripped over a major stumbling block. While it was true that more and more gadgets were becoming “smart,” in the sense of incorporating programmable microprocessors, the details of their digital designs varied enormously. Each program to link each individual model of, say, VCR into the home network would have to be written, tested, and debugged from scratch. Unless, that is, the program could be made to run in a virtual machine.

A virtual machine is an imaginary computer which a real computer can be programmed to simulate. It permits a “write once, run everywhere” approach to software: once a given real computer has an interpreter for a given virtual machine, it can run any and all programs that have been or will be written for that virtual machine, albeit at some cost in performance.

Like almost every other part of the programming language that would eventually become known as Java, the idea of a virtual machine was far from new in the abstract. (“In some sense, I would like to think that there was nothing invented in Java,” says Gosling.) For example, a decade before Gosling went to work on his virtual machine, the Apple Pascal compiler was already targeting one that ran on the lowly Apple II, even as the games publisher Infocom was distributing its text adventures across dozens of otherwise incompatible platforms thanks to its Z-Machine.

Unfortunately, Gosling’s new implementation of this old concept proved unable to solve by itself the original problem for which it had been invented. Even Wi-Fi didn’t exist at this stage, much less the likes of Bluetooth. Just how were all of these smart gadgets supposed to actually talk to one another, to say nothing of pulling down the regular software updates which Gosling envisioned as another benefit of his project? (Building a floppy-disk drive into every toaster was an obvious nonstarter.) After reluctantly giving up on their home of the future, the team pivoted for a while toward “interactive television,” a would-be on-demand streaming system much like our modern Netflix. But Sun had no real record in the consumer space, and cable-television providers and other possible investors were skeptical.

While Gosling was trying to figure out just what this programming language and associated runtime environment he had created might be good for, the World Wide Web was taking off. In July of 1994, a Sun programmer named Patrick Naughton did something that would later give Bill Gates nightmares: he wrote a fairly bare-bones Web browser in Java, more for the challenge than anything else. A couple of months later there came the eureka moment: Naughton and another programmer named Jonathan Payne made it possible to run other Java programs, or “applets” as they would soon be known, right inside their browser. They stuck one of the team’s old graphical demos on a server and clicked the appropriate link, whereupon they were greeted with a screen full of dancing Coca-Cola cans. Payne found it “breathtaking”: “It wasn’t just playing an animation. It was physics calculations going on inside a webpage!”

In order to appreciate his awe, we need to understand what a static place the early Web was. HTML, the “language” in which pages were constructed, was an abbreviation for “Hypertext Markup Language.” In form and function, it was more akin to a typesetting specification than a Turing-complete programming language like C or Pascal or Java; the only form of interactivity it allowed for was the links that took the reader from static page to static page, while its only visual pizazz came in the form of static in-line images (themselves a relatively recent addition to the HTML specification, thanks to NCSA Mosaic). Java stood to change all that at a stroke. If you could embed programs running actual code into your page layouts, you could in theory turn your pages into anything you wanted them to be: games, word processors, spreadsheets, animated cartoons, stock-market tickers, you name it. The Web could almost literally come alive.

The potential was so clearly extraordinary that Java went overnight from a moribund project on the verge of the chopping block to Sun’s top priority. Even Bill Joy, now living in blissful semi-retirement in Colorado, came back to Silicon Valley for a while to lend his prodigious intellect to the process of turning Java into a polished tool for general-purpose programming. There was still enough of the old-school hacker ethic left at Sun that management bowed to the developers’ demand that the language be made available for free to individual programmers and small businesses; Sun would make its money on licensing deals with bigger partners, who would pay for the Java logo on their products and the right to distribute the virtual machine. The potential of Java certainly wasn’t lost on Netscape’s Marc Andreessen, who had long been leading the charge to make the Web more visually exciting. He quickly agreed to pay Sun $750,000 for the opportunity to build Java into the Netscape Navigator browser. In fact, it was Andreessen who served as master of ceremonies at Java’s official coming-out party at a SunWorld conference on May 23, 1995 — i.e., three days before Bill Gates wrote his urgent Internet memo.

What was it that so spooked him about Java? On the one hand, it represented a possible if as-yet unrealized challenge to Microsoft’s own business model of selling boxed software on floppy disks or CDs. If people could gain access to a good word processor just by pointing their browsers to a given site, they would presumably have little motivation to invest in Microsoft Office, the company’s biggest cash cow after Windows. But the danger Java posed to Microsoft might be even more extreme. The most maximalist predictions, which were being trumpeted all over the techie press in the weeks after the big debut, had it that even Windows could soon become irrelevant courtesy of Java. This is what Microsoft’s own Ben Slivka meant when he said that “the Web is the next platform.” The browser itself would become the operating system from the perspective of the user, being supported behind the scenes only by the minimal amount of firmware needed to make it go. Once that happened, a new generation of cheap Internet devices would be poised to replace personal computers as the world now knew them. With all software and all of each person’s data being stored in the cloud, as we would put it today, even local hard drives might become passé. And then, with Netscape Navigator and Java having taken over the role of Windows, Microsoft might very well join IBM, the very company it had so recently displaced from the heights of power, in the crowded field of computing’s has-beens.

In retrospect, such predictions seem massively overblown. Officially labeled beta software, Java was in reality more like an alpha release at best at the time it was being celebrated as the Paris to Microsoft’s Achilles, being painfully crash-prone and slow. And even when it did reach a reasonably mature form, the reality of it would prove considerably less than the hype. One crippling weakness that would continue to plague it was the inability of a Java applet to communicate with the webpage that spawned it; applets ran in Web browsers, but weren’t really of them, being self-contained programs siloed off in a sandbox from the environment that spawned them. Meanwhile the prospects of applications like online word processing, or even online gaming in Java, were sharply limited by the fact that at least 95 percent of Web users were accessing the Internet on dial-up connections, over which even the likes of a single high-resolution photograph could take minutes to load. A word processor like the one included with Microsoft Office would require hours of downloading every time you wanted to use it, assuming it was even possible to create such a complex piece of software in the fragile young language. Java never would manage to entirely overcome these issues, and would in the end enjoy its greatest success in other incarnations than that of the browser-embedded applet.

Still, cooler-headed reasoning like this was not overly commonplace in the months after the SunWorld presentation. By the end of 1995, Sun’s stock price had more than doubled on the strength of Java alone, a product yet to see a 1.0 release. The excitement over Java probably contributed as well to Netscape’s record-breaking initial public offering in August. A cavalcade of companies rushed to follow in the footsteps of Netscape and sign Java distribution deals, most of them on markedly more expensive terms. Even Microsoft bowed to the prevailing winds on December 7 and announced a Java deal of its own. (BusinessWeek magazine described it as a “capitulation.”) That all of this was happening alongside the even more intense hype surrounding the release of Windows 95, an operating system far more expansive than any that had come out of Microsoft to date but one that was nevertheless of a very traditionalist stripe at bottom, speaks to the confusion of these go-go times when digital technology seemed to be going anywhere and everywhere at once.

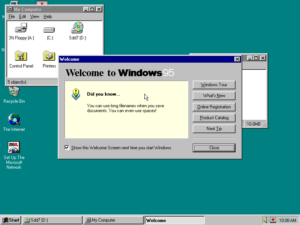

Whatever fear and loathing he may have felt toward Java, Bill Gates had clearly made his peace with the fact that the Web was computing’s necessary present and future. The Microsoft Network duly debuted as an icon on the default Windows 95 desktop, but it was now pitched primarily as a gateway to the open Web, with just a handful of proprietary features; MSN was, in other words, little more than yet another Internet service provider, of the sort that were popping up all over the country like dandelions after a summer shower. Instead of the 20 million subscribers that some had predicted (and that Steve Case had so feared), it attracted only about 500,000 customers by the end of the year. This left it no more than one-eighth as large as AOL, which had by now completed its own deft pivot from proprietary online service of the 1980s type to the very face of the World Wide Web in the eyes of countless computing neophytes.

Yet if Microsoft’s first tentative steps onto the Web had proved underwhelming, people should have known from the history of the company — and not least from the long, checkered history of Windows itself — that Bill Gates’s standard response to failure and rejection was simply to try again, harder and better. The real war for online supremacy was just getting started.

(Sources: the books Overdrive: Bill Gates and the Race to Control Cyberspace by James Wallace, The Silicon Boys by David A. Kaplan, Architects of the Web by Robert H. Reid, Competing on Internet Time: Lessons from Netscape and Its Battle with Microsoft by Michael Cusumano and David B. Yoffie, dot.con: The Greatest Story Ever Sold by John Cassidy, Stealing Time: Steve Case, Jerry Levin, and the Collapse of AOL Time Warner by Alec Klein, Fools Rush In: Steve Case, Jerry Levin, and the Unmaking of AOL Time Warner by Nina Munk, and There Must be a Pony in Here Somewhere: The AOL Time Warner Debacle by Kara Swisher.)