Act 1: Starcraft the Game

Great success brings with it great expectations. And sometimes it brings an identity crisis as well.

After Blizzard Entertainment’s Warcraft: Orcs and Humans became a hit in 1995, the company started down a very conventional path for a new publisher feeling its oats, initiating a diverse array of projects from internal and external development teams. In addition to the inevitable Warcraft sequel, there were a streamlined CRPG known as Diablo, a turn-based tactical-battle game known as Shattered Nations, a 4X grand-strategy game known as Pax Imperia II, even an adventure game taking place in the Warcraft universe — to be called, naturally enough, Warcraft Adventures. Then, too, even before Warcraft II: Tides of Darkness was finished, Blizzard had already started on a different sort of spinoff than Warcraft Adventures, one which jettisoned the fantasy universe but stayed within the same gameplay genre of real-time strategy. It was to be called Starcraft, and was to replace fantasy with science fiction. Blizzard thought that one team could crank it out fairly quickly using the existing Warcraft II engine, while another one retooled their core RTS technology for Warcraft III.

In May of 1996, with Warcraft II now six months old and a massive hit, Blizzard brought early demos of Starcraft and most of their other works in progress to E3, the games industry’s new annual showcase. One could make a strong argument that the next few days on the E3 show floor were the defining instant for the Blizzard brand as we still know it today.

The version of Starcraft that Blizzard brought to the 1996 E3 show. Journalists made fun of its fluorescent purple color palette among other things. Was this game being designed by Prince?

The gaming press was not particularly kind to the hodgepodge of products that Blizzard showed them at E3. They were especially cruel to Starcraft, which they roundly mocked for being exactly what it was, a thinly reskinned version of Warcraft II — or, as some journalists took to calling it, Orcs in Space. Everyone from Blizzard came home badly shaken by the treatment. So, after a period of soul searching and much fraught internal discussion, Blizzard’s co-founders Allen Adham and Mike Morhaime decided not to be quite so conventional in the way they ran their business. They took a machete to their jungle of projects which seemed to have spontaneously sprouted out of nowhere as soon as the money started to roll in. When all was said and done, they allowed only two of them to live on: Diablo, which was being developed at the newly established Blizzard North, of San Mateo, California; and Starcraft, down at Blizzard South in Irvine, California. But the latter was no longer to be just a spinoff. “We realized, this product’s just going to suck,” says Blizzard programmer Pat Wyatt of the state of the game at that time. “We need to have all our effort put into it. And everything about it was rebooted: the team that was working on it, the leadership, the design, the artwork — everything was changed.”

Blizzard’s new modus operandi would be to publish relatively few games, but to make sure that each and every one of them was awesome, no matter what it took. In pursuit of that goal, they would do almost everything in-house, and they would release no game before its time. The time of Starcraft, that erstwhile quickie Warcraft spinoff, wouldn’t come until March of 1998, while Warcraft III wouldn’t drop until 2002. In defiance of all of the industry’s conventional wisdom, the long gaps between releases wouldn’t prove ruinous; quite the opposite, in fact. Make the games awesome, Blizzard would learn, and the gamers will be there waiting with money in hand when they finally make their appearance.

Adham and Morhaime fostered as non-hierarchical a structure as possible at Blizzard, such that everyone, regardless of their ostensible role — from programmers to artists, testers to marketers — felt empowered to make design suggestions, knowing that they would be acted upon if they were judged worthy by their peers. Thus, although James Phinney and Chris Metzen were credited as “lead designers” on Starcraft, the more telling credit is the one that attributes the design as a whole simply to “Blizzard Entertainment.” The founders preferred to promote from within, retaining the entry-level employees who had grown up with the Blizzard Way rather than trying to acclimatize outsiders who were used to less freewheeling approaches. Phinney and Metzen were typical examples: the former had started at Blizzard as a humble tester, the latter as a manual writer and line artist.

For all that Blizzard’s ambitions for Starcraft increased dramatically over the course of its development, it was never intended to be a radical formal departure from what had come before. From start to finish, it was nothing more nor less than another sprite-based 2D RTS like Warcraft II. It was just to be a better iteration on that concept — so much better that it verged on becoming a sort of Platonic ideal for this style of game. Blizzard would keep on improving it until they started to run out of ideas for making it better still. Only then would they think about shipping it.

The exceptions to this rule of iteration rather than blue-sky invention all surrounded the factions that you could either control or play against. There were three of them rather than the standard two, for one thing. But far more importantly, each of the factions was truly unique, in marked contrast to those of Warcraft and Warcraft II. In those games, the two factions’ units largely mirrored one another in a tit-for-tat fashion, merely substituting different names and sprites for the same sets of core functions. Yet Starcraft had what Blizzard liked to call an “asymmetric” design; each of the three factions played dramatically differently, with none of the neat one-to-one correspondences that had been the norm within the RTS genre prior to this point.

In fact, the factions could hardly have been more different from one another. There were the Terrans, Marines in space who talked like the drill sergeant in Full Metal Jacket and fought with rifles and tanks made out of good old reliable steel; the Zerg, an insectoid alien race in thrall to a central hive mind, all crunchy carapaces and savage slime; and the Protoss, aloof, enigmatic giants who could employ psionic powers as devastatingly as they could their ultra-high-tech weaponry.

The single-player campaign in which you got to take the factions for a spin was innovative in its way as well. Instead of asking you to choose a side to control at the outset, the campaign expected you to play all three of them in succession, working your way through a sprawling story of interstellar conflict, as told in no fewer than 30 individual scenarios. It cleverly began by placing you in control of the Terrans, the most immediately relatable faction, then moved on to the movie-monster-like Zerg and finally the profoundly alien Protoss once you’d gotten your sea legs.

Although it seems safe to say that the campaign was never the most exciting part of Starcraft for the hyper-competitive young men at Blizzard, they didn’t stint on the effort they put into it. They recognized that the story and cinematics of Westwood Studio’s Command & Conquer — all that stuff around the game proper — was the one area where that arch-rival RTS franchise had comprehensively outdone them to date. Determined to rectify this, they hired Harley D. Huggins II, a fellow who had done some CGI production on the recent film Starship Troopers — a movie whose overall aesthetic had more than a little in common with Starcraft — as the leader of their first dedicated cinematics team. The story can be a bit hard to follow, what with its sometimes baffling tangle of groups who are forever allying with and then betraying one another, the better to set up every possible permutation of battle. (As Blizzard wrote on their back-of-the-box copy, “The only allies are enemies!”) Still, no one can deny that the campaign is presented really, really well, from the cut-scenes that come along every few scenarios to the voice acting during the mission briefings, which turn into little audio dramas in themselves. That said, a surprising amount of the story is actually conveyed during the missions, when your objectives can unexpectedly change on a dime; this was new to the RTS genre.

One of the cut-scenes which pop up every few scenarios during the campaign. Blizzard’s guiding ethic was to make them striking but short, such that no one would be tempted to skip them. Their core player demographic was not known for its patience with long-winded exposition…

Nonetheless, any hardcore Starcraft player will tell you that multiplayer is where it’s really at. When Blizzard released Diablo in the dying days of 1996, they debuted alongside it Battle.net, a social space and matchmaking service for multiplayer sessions over the Internet. Its contribution to Diablo’s enormous success is incalculable. Starcraft was to be the second game supported by the service, and Blizzard had no reason to doubt that it would prove just as important if not more so to their latest RTS.

If all of Starcraft was to be awesome, multiplayer Starcraft had to be the most awesome part of all. This meant that the factions had to be balanced; it wouldn’t do to have the outcome of matches decided before they even began, based simply upon who was playing as whom. After the basic framework of the game was in place, Blizzard brought in a rare outsider, a tireless analytical mind by the name of Rob Pardo, to be a sort of balance specialist, looking endlessly for ways to break the game. He not only played it to exhaustion himself but watched match after match, including hundreds played over Battle.net by fans who were lucky enough to be allowed to join a special beta program, the forerunner of Steam Early Access and the like of today. Rather than merely erasing the affordances that led to balance problems — affordances which were often among the funnest parts of the game — Pardo preferred to tweak the numbers involved and/or to implement possible countermeasures for the other factions, then throw the game out for yet another round of testing. This process added months to the development cycle, but no one seemed to mind. “We will release it when it’s ready,” remained Blizzard’s credo, in defiance of holidays, fiscal quarters, and all of the other everyday business logic of their industry. Luckily, the ongoing strong sales of Warcraft II and Diablo gave them that luxury.

Indeed, Blizzard veterans like to joke today that Starcraft was just two months away from release for a good fourteen months. They crunched and crunched and crunched, living lifestyles that were the opposite of healthy. “Relationships were destroyed,” admits Pat Wyatt. “People got sick.” At last, on March 27, 1998, the exhausted team pronounced the game done and sent it off to be pressed onto hundreds of thousands of CDs. The first boxed copies reached store shelves four days later.

Starcraft was a superb game by any standard, the most tactically intricate, balanced, and polished RTS to date, arguably for years still to come. It was familiar enough not to intimidate, yet fresh enough to make the purchase amply justifiable. Thanks to all of these qualities, it sold more than 1.5 million copies in the first nine months, becoming the biggest new computer game of the year. By the end of 1998, Battle.net was hosting more than 100,000 concurrent users during peak hours. Blizzard was now the hottest name in computer gaming; they had left even id Software — not to mention Westwood of Command & Conquer fame — in their dust.

There was always a snowball effect when it came to online games in particular; everyone wanted the game their friends were already playing, so that they too could get in on the communal fun. Thus Starcraft continued to sell well for years and years, flirting with 10 million units worldwide before all was said and done, by which time it had become almost synonymous with the RTS in general for many gamers. Although your conclusions can vary depending on where you move the goalposts — Myst sold more units during the 1990s — Starcraft has at the very least a reasonable claim to the title of most successful single computer game of its decade. Everyone who played games during its pre- and post-millennial heyday, everyone who had a friend that did so, everyone who even had a friend of a friend that did so remembers Starcraft today. It became that inescapable. And yet the Starcraft mania in the West was nothing compared to the fanaticism it engendered in one mid-sized Asian country.

If you had told the folks at Blizzard on the day they shipped Starcraft that their game would soon be played for significant money by professional teams of young people who trained as hard or harder than traditional athletes, they would have been shocked. If you had told them that these digital gladiators would still be playing it fifteen years later, they wouldn’t have believed you. And if you had told them that all of this would be happening in, of all places, South Korea, they would have decided you were as crazy as a bug in a rug. But all of these things would come to pass.

Act 2: Starcraft and the Rise of Gaming as a Spectator Sport

Why Starcraft? And why South Korea?

We’ve gone a long way toward answering the first question already. More than any RTS that came before it and the vast majority of those that came after it, Starcraft lent itself to esport competition by being so incredibly well-balanced. Terran, Zerg, or Protoss… you could win (and lose) with any of them. The game was subtle and complex enough that viable new strategies would still be appearing a decade after its release. At the same time, though, it was immediately comprehensible in the broad strokes and fast-paced enough to be a viable spectator sport, with most matches between experienced players wrapping up within half an hour. A typical Command & Conquer or Age of Empires match lasted about twice as long, with far more downtime when little was happening in the way of onscreen excitement.

The question of why South Korea is more complicated to answer, but by no means impossible. In the three decades up to the mid-1990s, the country’s economy expanded like gangbusters. Its gross national product increased by an average of 8.2 percent annually, with average annual household income increasing from $80 to over $10,000 over that span. In 1997, however, all of that came to a crashing halt for the time being, when an overenthusiastic and under-regulated banking sector collapsed like a house of cards, resulting in the worst recession in the country’s modern history. The International Monetary Fund had to step in to prevent a full-scale societal collapse, an intervention which South Koreans universally regarded as a profound national humiliation.

This might not seem like an environment overly conducive to a new fad in pop culture, but it proved to be exactly that. The economic crash left a lot of laid-off businessmen — in South Korea during this era, they were always men — looking for ways to make ends meet. With the banking system in free fall, there was no chance of securing much in the way of financing. So, instead of thinking on a national or global scale, as they had been used to doing, they thought about what they could do close to home. Some opened fried-chicken joints or bought themselves a taxicab. Others, however, turned to Internet cafés — or “PC bangs,” as they were called in the local lingo.

Prior to the economic crisis, the South Korean government hadn’t been completely inept by any means. It had seen the Internet revolution coming, and had spent a lot of money building up the country’s telecommunications infrastructure. But in South Korea as in all places, the so-called “last mile” of Internet connectivity was the most difficult to bring to an acceptable fruition. Even in North America and Western Europe, most homes could only access the Internet at this time through slow and fragile dial-up connections. South Korean PC bangs, however, jacked directly into the Internet from city centers, justifying the expense of doing so with economies of scale: 20 to 100 computers, each with a paying customer behind the screen, were a very different proposition from a single computer in the home.

The final ingredient in the cultural stew was another byproduct of the recession. An entire generation of young South Korean men found themselves unemployed or underemployed. (Again, I write about men alone here because South Korea was a rigidly patriarchal society at that time, although this is slowly — painfully slowly — changing now.) They congregated in the PC bangs, which gave them unfettered access to the Internet for about $2 per hour. It was hard to imagine a cheaper form of entertainment. The PC bangs became social scenes unto themselves, packed at all hours of the day and night with chattering, laughing youths who were eager to forget the travails of real life outside their four walls. They drank bubble tea and slurped ramen noodles while, more and more, they played online games, both against one another and against the rest of the country. In a way, they actually had it much better than the gamers who were venturing online in the Western world: they didn’t have to deal with all of the problems of dial-up modems, could game on rock-solid connections running at speeds of which most Westerners could only dream.

A few months after it had made its American debut, Starcraft fell out of the clear blue South Korean sky to land smack dab in the middle of this fertile field. The owners of the PC bangs bought copies and installed them for their customers’ benefit, as they already had plenty of other games. But something about Starcraft scratched an itch that no PC-bang patron had known he had. The game became a way of life for millions of South Koreans, who became addicted to the adrenaline rush it provided. Soon many of the PC bangs could be better described as Starcraft bangs. Primary-school children and teenagers hung out there as well as twenty-somethings, playing and, increasingly, just watching others play, something you could do for free. The very best players became celebrities in their local community. It was an intoxicating scene, where testosterone rather than alcohol served as the social lubricant. Small wonder that the PC bangs outlived the crisis that had spawned them, remaining a staple of South Korean youth culture even after the economy got back on track and started chugging along nicely once again. In 2001, long after the crisis had passed, there were 23,548 PC bangs in the country, roughly the same number of Internet cafés as there were 7-Elevens.

Of course, the PC bangs were all competing with one another to lure customers through their doors. The most reliable way to do so was to become known as the place where the very best Starcraft players hung out. To attract such players, some enterprising owners began hosting tournaments, with prizes that ranged from a few hours of free computer time to up to $1000 in cash. This was South Korean esports in their most nascent form.

The impresario who turned Starcraft into a professional sport as big as any other in the country was named Hwang Hyung Jun. During the late 1990s, Hwang was a content producer at a television station called Tooniverse, whose usual fare was syndicated cartoons. He first started to experiment with videogame programming in the summer of 1998, when he commemorated that year’s World Cup of Football by broadcasting simulated versions of each match, played in Electronic Arts’s World Cup 98. That led to other experiments with simulated baseball. (Chan Ho Park, the first South Korean to play Major League Baseball in North America, was a superstar on two continents at that time.)

But it was only when Hwang tried organizing and broadcasting a Starcraft tournament in 1999 that he truly hit paydirt. Millions were instantly entranced. Among them was a young PC bang hanger-on and Starcraft fanatic named Baro Hyun, who would go on to write a book about esports in his home country.

Late one afternoon, I returned from school, unloaded my backpack, and turned on the television in the living room. Thanks to my parents, we had recently subscribed to a cable-TV network with dozens of channels. As a cable-TV newbie, I navigated my way through what felt like a nearly infinite number of channels. Movie channel; next. Sports channel; next. Professional Go channel; popular among fathers, but a definite next for me.

Suddenly I stopped clicking and stared open-mouthed at the television. I could not believe what I was seeing. A one-on-one game of Starcraft was on TV.

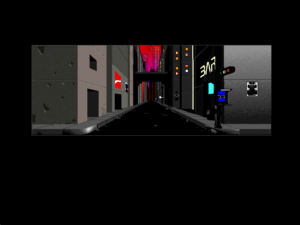

Initially, I thought I’d stumbled across some sort of localized commercial made by Blizzard. Soon, however, it became obvious that wasn’t the case. The camera angle shifted from the game screen to the players. They were oddly dressed, like budget characters in Mad Max. Each one wore a headset and sat in front of a dedicated PC. They appeared to be engaged in a serious Starcraft duel.

This was interesting enough, but when I listened carefully, I could hear commentators explaining what was happening in the game. One explained the facts and game decisions of the players, while another interpreted what those decisions might mean to the outcome of the game. After the match, the camera angle switched to the caster and the commentators, who briefed viewers on the result of the game and the overall story. The broadcast gave the unmistakable impression of a professional sports match.

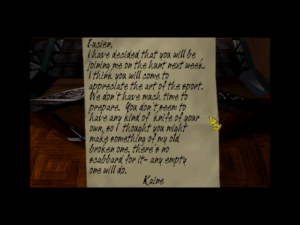

Esports history is made, as two players face off in one of the first Starcraft matches ever to be broadcast on South Korean television, from a kitschy set that looks to have been constructed from the leavings of old Doctor Who episodes.

These first broadcasts corresponded with the release of Brood War, Starcraft’s first and only expansion pack. Its development had been led by the indefatigable Rob Pardo, who used it to iron out the last remaining balance issues in the base game. (“Starcraft [alone] was not a game that could have been an esport,” wrote a super-fan bluntly years later in an online “Brief History of Starcraft.” “It was [too] simple and imbalanced.”)

Now, the stage was set. Realizing he had stumbled upon something with almost unlimited potential, Hwang Hyung Jun put together a full-fledged national Starcraft league in almost no time at all. From the bottom rungs at the level of the local PC bangs, players could climb the ladder all the way to the ultimate showcase, the “Tooniverse Starleague” final, in which five matches were used to determine the best Starcraft player of them all. Surprisingly, when the final was held for the first time in 2000, that player turned out to be a Canadian, a fellow named Guillaume Patry who had arrived in South Korea just the year before.

No matter; the tournament put up ratings that dwarfed those of Tooniverse’s usual programming. Hwang promptly started his own television channel. Called OnGameNet, it was the first in the world to be dedicated solely to videogames and esports. The Starcraft players who were featured on the channel became national celebrities, as did the sportscasters and color commentators: Jung Il Hoon, who looked like a professor and spoke in the stentorian tones of a newscaster; Jeon Yong Jun, whom words sometimes failed when things got really exciting, yielding to wild water-buffalo bellowing; Jung Sorin, a rare woman on the scene, a kindly and nurturing “gamer mom.” Their various shticks may have been calculated, but they helped to make the matches come alive even for viewers who had never played Starcraft for themselves.

A watershed was reached in 2002, when 20,000 screaming fans packed into a Seoul arena to witness that year’s final. The contrast with just a few years before, when a pair of players had dueled on a cheap closed set for the sake of mid-afternoon programming on a third-tier television station, could hardly have been more pronounced. Before this match, a popular rock band known as Cherry Filter put on a concert. Then, accepting their unwonted opening-act status with good grace, the rock stars sat down to watch the showdown between Lim Yo Hwan and Park Jung Seok on the arena’s giant projection screens, just like everyone else in the place. Park, who was widely considered the underdog, wound up winning three matches to one. Even more remarkably, he did so while playing as the Protoss, the least successful of the three factions in professional competitions prior to this point.

Losing the 2002 final didn’t derail Lim Yo Hwan’s career. He went on to become arguably the most successful Starcraft player in history. He was definitely the most popular during the game’s golden age in South Korea. His 2005 memoir, advising those who wanted to follow in his footsteps to “practice relentlessly” and nodding repeatedly to his sponsors — he wrote of opening his first “Shinhan Bank account” as a home for his first winnings — became a bestseller.

Everything was in flux; new tactics and techniques were coming thick and fast, as South Korean players pushed themselves to superhuman heights, the likes of which even the best players at Blizzard could scarcely have imagined. By now, they were regularly performing 250 separate actions per minute in the game.

The scene was rapidly professionalizing in all respects. Big-name corporations rushed in to sponsor individual players and, increasingly, teams, who lived together in clubhouses, neglecting education and all of the usual pleasures of youth in favor of training together for hours on end. The very best Starcraft players were soon earning hundreds of thousands of dollars per year from prize money and their sponsorship deals.

Baseball had long been South Korea’s most popular professional sport. In 2004, 30,000 people attended the baseball final in Seoul. Simultaneously, 100,000 people were packing a stadium in Busan, the country’s second largest city, for the OnGameNet Starcraft final. Judged on metrics like this one, Starcraft had a legitimate claim to the title of most popular sport of all in South Korea. The matches themselves just kept getting more intense; some of the best players were now approaching 500 actions per minute. Maintaining a pace like that required extraordinary reflexes and mental and physical stamina — reflexes and stamina which, needless to say, are strictly the purview of the young. Indeed, the average professional Starcraft player was considered washed up even younger than the average soccer player. Women weren’t even allowed to compete, out of the assumption that they couldn’t possibly be up to the demands of the sport. (They were eventually given a league of their own, although it attracted barely a fraction of the interest of the male leagues — sadly, another thing that Starcraft has in common with most other professional sports.)

Ten years after Starcraft’s original release as just another boxed computer game, it was more popular than ever in South Korea. The PC bangs had by now fallen in numbers and importance, in reverse tandem with the rise in the number of South Korean households with computers and broadband connections of their own. Yet esports hadn’t missed a beat during this transition. Millions of boys and young men still practiced Starcraft obsessively in the hopes of going pro. They just did it from the privacy of their bedrooms instead of from an Internet café.

Starcraft fandom in South Korea grew up alongside the music movement known as K-pop, and shares many attributes with it. Just as K-pop impresarios absorbed lessons from Western boy bands, then repurposed them into something vibrantly and distinctly South Korean, the country’s Starcraft moguls made the game their own; relatively few international tournaments were held, simply because nobody had much chance of beating the top South Korean players. There was an almost manic quality to both K-pop and the professional Starcraft leagues, twin obsessions of a country to which the idea of a disposable income and the consumerism it enables were still fairly new. South Korea’s geographical and geopolitical positions were precarious, perched there on the doorstep of giant China alongside its own intransigent and bellicose mirror image, a totalitarian state hellbent on acquiring nuclear weapons. A mushroom cloud over Seoul suddenly ending the party remained — and remains — a very real prospect for everyone in the country, giving ample reason to live for today. Rather than the decadent hedonism that marked, say, Cold War Berlin, South Korea turned to a pop culture of giddy, madding innocence for relief.

Alas, though, it seems that all forms of sport must eventually pass through a loss of innocence. Starcraft’s equivalent of the 1919 Major League Baseball scandal started with Ma Jae-yoon, a former superstar who by 2010 was struggling to keep up with the ever more demanding standard of play. Investigating persistent rumors that Ma was taking money to throw some of his matches, the South Korean Supreme Prosecutors’ Office found that they were truer than anyone had dared to speculate. Ma stood at the head of a conspiracy with as many tendrils as a Zerg, involving the South Korean mafia and at least a dozen other players. The scandal was front-page news in the country for months. Ma ended up going to prison for a year and being banned for life from South Korean esports. (“Say it ain’t so, Ma!”) His crimes cast a long shadow over the Starcraft scene; a number of big-name sponsors pulled out completely.

The same year as the match-fixing scandal, Blizzard belatedly released Starcraft II: Wings of Liberty. Yet another massive worldwide hit for its parent company, the sequel proved a mixed blessing for South Korean esports. The original Starcraft had burrowed its way deep into the existing players’ consciousnesses; every tiny quirk in the code that Blizzard had written so many years earlier had been dissected, internalized, and exploited. Many found the prospect of starting over from scratch deeply unappealing; perhaps there is space in a lifetime to learn only one game as deeply as millions of South Korean players had learned the first Starcraft. Some put on a brave face and tried to jump over to the sequel, but it was never quite the same. Others swore that they would stop playing the original only when someone pried it out of their cold, dead hands — but that wasn’t the same either. A third, disconcertingly large group decided to move on to some other game entirely, or just to move on with life. By 2015, South Korean Starcraft was a ghost of its old self.

Which isn’t to say that esports as a whole faded away in the country. Rather than Starcraft II, a game called League of Legends became the original Starcraft’s most direct successor in South Korea, capable of filling stadiums with comparable numbers of screaming fans. (As a member of a newer breed known as “multiplayer online battle arena” (MOBA) games, League of Legends is similar to Starcraft in some ways, but very different in others; each player controls only a single unit instead of amassing armies of them.) Meanwhile esports, like K-pop, were radiating out from Asia to become a fixture of global youth culture. The 2017 international finals of League of Legends attracted 58 million viewers all over the world; the Major League Baseball playoffs that year managed just 38 million, the National Basketball Association finals only 32 million. Esports are big business. And with annual growth rates in the double digits in percentage terms, they show every sign of continuing to get bigger and bigger for years to come.

How we feel about all of this is, I fear, dictated to a large extent by the generation to which we happen to belong. (Hasn’t that always been the way with youth culture?) Being a middle-aged man who grew up with digital games but not with gaming as a spectator sport, my own knee-jerk reaction vacillates between amusement and consternation. My first real exposure to esports came not that many years ago, via an under-sung little documentary film called State of Play, which chronicles the South Korean Starcraft scene, fly-on-the-wall style, just as its salad days are coming to an end. Having just re-watched the film before writing this piece, I still find much of it vaguely horrifying: the starry-eyed boys who play Starcraft ten to fourteen hours per day; the coterie of adult moguls and handlers who are clearly making a lot of money by… well, it’s hard for me not to use the words “exploiting them” here. At one point, a tousle-headed boy looks into the camera and says, “We don’t really play for fun anymore. Mostly I play for work. My work just happens to be a game.” That breaks my heart every time. Certainly this isn’t a road that I would particularly like to see any youngster I care about go down. A happy, satisfying life, I’ve long believed, is best built out of a diversity of experiences and interests. Gaming can be one of these, as rewarding as any of the rest, but there’s no reason it should fill more than a couple of hours of anyone’s typical day.

On the other hand, these same objections perchance apply equally to sports of the more conventionally athletic kind. Those sports’ saving grace may be that it’s physically impossible to train at most of them for ten to fourteen hours at a stretch. Or maybe it has something to do with their being intrinsically healthy activities when pursued in moderation, or with the spiritual frisson that can come from being out on the field with grass underfoot and sun overhead, with heart and lungs and limbs all pumping in tandem as they should. Just as likely, though, I’m merely another old man yelling at clouds. The fact is that a diversity of interests is usually not compatible with ultra-high achievement in any area of endeavor.

Anyway, setting the Wayback Machine to 1998 once again, I can at least say definitively that gaming stood on the verge of exploding in unanticipated, almost unimaginable directions at that date. Was Starcraft the instigator of some of that, or was it the happy beneficiary? Doubtless a little bit of both. Blizzard did have a way of always being where the action was…

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Stay Awhile and Listen, Book II by David L. Craddock and Demystifying Esports by Baro Hyun; Computer Gaming World of May 1997, September 1997, and July 1998; Retro Gamer 170; International Journal of Communication 14; the documentary film State of Play.

Online sources include Soren Johnson’s interview of Rob Pardo for his Designer’s Notes podcast, “Behind the Scenes of Starcraft’s Earliest Days” by Kat Bailey at VG247, and “A Brief History of Starcraft“ at TL.net.

Starcraft and the Brood War expansion are now available for free at Blizzard’s website.