After Edison’s original phonograph came out, people said that they could not detect a difference between a phonograph and a real performance. Clearly the standard that they had for audio fidelity back in 1910 was radically different from the standard we have. They got the same enjoyment out of that Edison phonograph that we do out of [a] high-fidelity [stereo]. As audio fidelity has gotten better and better, our standards have gotten higher and higher; if we listen to a phonograph from 1910, it sounds horrible to our modern ears.

The same thing has obviously happened to flight simulators.

— Brand Fortner, 2010

It seems to me that vintage flight simulators have aged worse than just about any other genre of game. No, they weren’t the only games that required a large helping of imagination to overlook their underwhelming audiovisuals, that had sometimes to ask their players to see them as what they aspired to be rather than what they actually were. But they were perhaps the ones in which this requirement was most marked. When we look back on them today, we find ourselves shaking our heads and asking what the heck we were all thinking.

Growing up in the 1980s, I certainly wasn’t immune to the appeal of virtual flight; I spent many hours with subLogic’s Flight Simulator II and MicroProse’s Gunship on my Commodore 64, then hours more with F/A-18 Interceptor on my Commodore Amiga. Revisited today, however, all of those games strike me as absurdly, unplayably primitive. Therefore they and the many games like them have appeared in these histories only in the form of passing mentions.

The case of flight simulators thus serves to illustrate some of the natural tensions implicit in what I do here. On the one hand, I want to celebrate the games that still stand up today, maybe even get some of you to try them for the first time all these years later — and I’ve yet to find a vintage flight simulator which I can recommend on those terms. But on the other hand, I want to sketch an accurate, non-anachronistic picture of these bygone eras of gaming as they really were. In this latter sense, my efforts to date have been sadly inadequate in the case of flight simulators; the harsh fact is that these games which I’ve neglected so completely were in fact among the most popular of their time, accounting on occasion for as much as 25 percent of the computer-game industry’s total revenue. Microsoft Flight Simulator, the prototypical and perennial product of its type, was the most commercially successful single franchise in all of computer gaming between 1982 and 1995 — all despite having no goals other than the ones you set for yourself and for the most part no guns either. (Let that sink in for a moment!)

All of which is to say that a reckoning is long overdue here. This article, while it may not quite give Microsoft Flight Simulator and its siblings their due, will at least begin to redress the balance.

Many people assumed in the 1980s, as they still tend to do today, that the early microcomputer flight simulators were imperfect imitations of the bigger simulators that were used to train pilots for real-world flying. In point of fact, though, the relationship between the two was more subtle — even more symbiotic — than one might guess. To appreciate how this could be, we need to remember that the 3D-graphics techniques that were being used to power all flight simulators by the 1980s were a new technology at the time — new not just to microcomputers but to all computers. Until the 1980s, the “big” flight simulators made for training purposes were very different beasts from the ones that came later.

That said, the idea of flight simulation in general goes back a long, long way, almost all the way back to the dawn of powered flight itself. It took very little time at all after Orville and Wilbur Wright made their first flights in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, for people to start asking how they might train new pilots in some more forgiving, less dangerous way than putting them behind the controls of a real airplane and hoping for the best. A 1910 issue of Flight magazine — the “first aero weekly in the world” — describes the “Sanders Teacher,” a mock-up of a real airplane mounted on a pivoting base so that it could sway with the wind in response to control inputs; unlike the fragile real aircraft of its era, this one was best “flown” when there was a stiff breeze.

In 1929, Edwin Link of Binghamton, New York, created the Link Trainer, the first flight simulator that we might immediately recognize as such today. An electro-mechanical device driven by organ bellows in its prototype form, it looked like an amputated single-seater-airplane cockpit. The entire apparatus pitched and turned in response to a trainee’s movements of the controls therein, while an instructor sat next to the gadget to evaluate his performance. After an initially skeptical response from the market, usage of the Link Trainer around the world exploded with the various military buildups that began in the mid-1930s. It was used extensively, in both its official incarnation and in unlicensed knock-offs, by virtually every combatant nation in World War II; it was a rite of passage for tens of thousands of new pilots, marking the most widespread use of technology in the cause of simulation to that point in the history of the world.

The programmable digital computers which began to appear after the war held out the prospect of providing a more complete simulation of all aspects of flight than analog devices like the Link Trainer and its successors could hope to achieve. Already in 1950, the United States Navy funded a research effort in that direction at the University of Pennsylvania. Yet it wasn’t until ten years later that the first computerized flight simulators began to appear. Once again, Link Aviation Devices provided the breakthrough machine here, in the form of the Link Mark 1, whose three processors shared 10 K of memory to present the most credible imitation of real flight yet, with even wind and engine noise included if you bought the most advanced model. By 1970, virtually all flight simulators had gone digital.

But there was a persistent problem afflicting all of these efforts at flight simulation, even after the dawn of the digital age. Although the movements of cockpit instruments and even the physical motion of the aircraft itself could be practically implemented, the view out the window could not. What these machines thus wound up simulating was a totally blind form of flying, as in the heaviest of fogs or the darkest of nights, when the pilot has only her instruments to guide her. Flying-by-instruments was certainly a useful skill to have, but the inability of the simulators to portray even a ground and horizon for the pilot to sight on was a persistent source of frustration to those who dreamed of simulating flight as it more typically occurred in the real world.

Various schemes were devised to remedy the situation, some using reels of film that were projected on the “windows” of the cockpit, some even using a moving video camera which “flew” over model terrain. But snippets of static video are a crude tool indeed in an interactive context, and none of these solutions yielded anything close to the visual impression of real flight. What was needed was an out-the-window view that was generated on the fly in real time by the computer.

In 1973, McDonnell-Douglas introduced the VITAL II, a computerized visual display which could be added to existing flight simulators. Even its technology, however, was different in a fairly fundamental sense from that of the flight simulators that would appear later. The computers which ran the latter would use what’s known as raster-based or bitmap graphics: a grid of pixels stored in memory, which are painted to the monitor screen by the computer’s display circuitry without additional programming. VITAL II, by contrast, used something known as vector graphics, in which the computer’s processor directly controls the electron gun inside the display screen, telling it where to go and when to fire to produce an image on the screen. Although bitmap graphics are far easier for the programmer to work with and more flexible in countless ways, they do eat up memory, a commodity which most computers of the early 1970s had precious little of to spare. Therefore vector graphics were still being used for many applications, including this one.

Thanks to the limitations of its hardware, the VITAL II could only show white points of light on the surface of a black screen, and thus could only be used to depict a night flight. Indeed, it showed only lights — the lights of runways, airports, and to some extent their surrounding cities.

Such was the state of the art in flight simulation during the mid-1970s, when a young man named Bruce Artwick was attending the University of Illinois in Champaign.

Flight simulators aside, this university occupies an important place in the history of computing in that it was the home of PLATO, the pioneering computer network that anticipated much of the digital culture that would come two decades or more after it. A huge variety of games were developed for PLATO, including the first CRPGs and, most importantly for our purposes today, the first flight simulator to be intended for entertainment and casual exploration rather than professional pilot training. Brand Fortner’s game of Airfight wasn’t quite a real-time simulation as we think of it today — you had to hit the NEXT key over and over to update the screen — but it could almost feel like it ran in real time to those willing and able to pound their keyboards with sufficient gusto. Brian Dear described the experience in his book about the PLATO system:

By today’s standards, Airfight’s graphics and realism, like every other PLATO game, are hopelessly primitive. But in the 1970s Airfight was simply unbelievable. These rooms full of PLATO terminals weren’t “PLATO classrooms,” they were PLATO arcades, and they were free. If you were lucky enough to get in (there were always more people wanting to play than the game could handle), you joined the Circle or the Triangle teams, chose from a list of different airplane types to fly, and suddenly found yourself in a fighter plane, looking out of the cockpit window at the runway in front of you, with the control tower far down the runway… You’d hit “9” to set the throttle at maximum, “a” for afterburners, “w” a few times to pull the stick back, and then NEXT NEXT NEXT NEXT NEXT NEXT NEXT to update the screen as you rolled down the runway, lifted off, and shot up into the sky to join the fight. It might be seconds or minutes, depending on how far away the enemy airplanes were, before you saw dots in the sky, dots that as you flew closer and closer turned into little circles and triangles. (So they weren’t photorealistic airplanes — it didn’t matter. You didn’t notice. This was battle. This was Airfight.) As you got closer and closer to one of these planes, the circles and triangles got more defined — still small, still pathetically primitive by today’s standards — but you knew you were getting closer and that’s all that mattered. As you got closer and closer you hit “s” to put up your sights, to aim. Eventually, if you were good, lucky, or both, you would be so close that you’d see a little empty space, an opening, inside the little circle or triangle icon. That’s when you were close enough to see what players called “the whites of their eyes” and that’s when you let ’em have it: SHIFT-S to shoot. SHIFT-S again. And again. Until you’d run out of ammo and KABOOM! It was glorious.

And it was addictive. People stayed up all night playing Airfight. If you went to a room full of PLATO terminals, you’d hear the clack-clack-clack-clack-clack-CLACKETY-CLACK-CLACK-BAM-BAM!-WHAM!-CLACK-CLACK! of everyone’s keyboards, as the gamers pounded them, mostly NEXT-NEXT-NEXT’ing to update their view and their radar displays (another innovation of this game — in-cockpit radar displays, showing you where the enemy was).

The standard PLATO terminal at that time was an astonishingly advanced piece of hardware to place at the disposal of everyday university students: a monochrome bitmap display of no less than 512 X 512 pixels. Thus Airfight, in addition to being the first casual flight simulator, was the first flight simulator of any kind to use a bitmap display. This fact wasn’t lost on Bruce Artwick when he first saw the game in action — for Artwick already knew a little something about the state of the art in serious flight simulation.

The University of Illinois’s Institute of Aviation was one of the premiere aerospace programs in the country, training both engineers and pilots. Artwick happened to be pursuing a master’s degree in general electrical engineering, but he roomed with one of the university’s so-called “aviation jocks”: an accomplished pilot named Stu Moment, who was training to become a flight instructor at the same time that he pursued a degree in business. “We agreed that Stu would teach me to fly if I taught him about digital electronics,” Artwick remembers. Although Artwick’s electrical-engineering program would seemingly mark him as a designer of hardware, the technological disciplines were more fluid in the 1970s than they’ve become today. His real passion, indulged willingly enough by his professors, had turned out to be the nascent field of bitmap 3D graphics. So, he found himself with one foot in the world of 3D programming, the other in that of aviation: the perfect resumé for a maker of flight simulators.

Airfight hit Artwick like a revelation. In a flash, he understood that the PLATO terminal could become the display technology behind a flight simulator used for more serious purposes. He sought and received funding from the Office of Naval Research to make a prototype 3D display useful for that purpose as his master’s thesis. Taking advantage of his knowledge of hardware engineering, he managed to connect a PLATO terminal to one of the DEC PDP-11 minicomputers used at the Aviation Institute. He then employed this setup to create what his final thesis called “a versatile computer-generated flight display,” submitting his code and a 60-page description of its workings to his instructors and to the Office of Naval Research.

It’s hard to say whether Artwick’s thesis, which he completed in May of 1976, was at all remarked among the makers of flight simulators already in use for pilot training. Many technical experiments like it came out of the aerospace-industrial complex’s web of affiliated institutions, sometimes to languish in obscurity, sometimes to provide a good idea or two for others to carry forward, but seldom to be given much credit after the fact. We can say, however, that by the end of the 1970s the shift to bitmap graphics was finally beginning among makers of serious flight simulators. And once begun, it happened with amazing speed; by the mid-1980s, quite impressive out-the-cockpit views, depicting nighttime or daytime scenery in full color, had become the norm, making the likes of the VITAL II system look like the most primordial of dinosaurs.

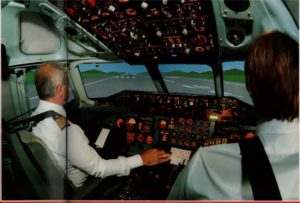

This photo from a 1986 brochure by a flight-simulator maker known as Rediffusion Simulation shows how far the technology progressed in a remarkably short period of time after bitmap 3D graphics were first introduced on the big simulators. Although the graphical resolution and detail are vastly less than one would find in a simulator of today, the Rubicon has already been crossed. From now on, improvements will be a question of degree rather than kind.

Meanwhile the same technology was coming home as well, looking a bit less impressive than the state-of-the-art simulators in military and civilian flight schools but a heck of a lot better than VITAL II. And Artwick’s early work on that PLATO terminal most definitely was a pivotal building block toward these simulators, given that the most important person behind them was none other than Artwick himself.

After university, Artwick parlayed his thesis into a job with Hughes Aircraft in California, but found it difficult to develop his innovations further within such a large corporate bureaucracy. His now-former roommate Stu Moment started working as a flight instructor right there in Champaign, only to find that equally unsatisfying. In early 1977, the two decided to form a software company to serve the new breed of hobbyist-oriented microcomputers. It was an auspicious moment to be doing so; the Trinity of 1977 — the Apple II, Radio Shack TRS-80, and Commodore PET, constituting the first three pre-assembled personal computers — was on the near horizon, poised to democratize the hobby for those who weren’t overly proficient with a soldering iron. Artwick and Moment named their company subLogic, after a type of computer circuit. It would prove a typical tech-startup partnership in many ways: the reserved, retiring Artwick would be the visionary and the technician, while the more flamboyant, outgoing Moment would be the manager and the salesman.

Artwick and Moment didn’t initially conceive of their company as a specialist in flight simulators; they rather imagined their specialty to be 3D graphics in all of their potential applications. Accordingly, their first product was “The subLogic Three-Dimensional Micrographics Package,” a set of libraries to help one code one’s own 3D graphics in the do-it-yourself spirit of the age. Similar technical tools continued to occupy them for the first couple of years, even as both partners continued to work their day jobs, hoping that grander things might await them in the future, once the market for personal computers had had time to mature a bit more.

In June of 1979, they decided that moment had come. Artwick quit his job at Hughes and joined Moment back in Champaign, where he started to work on subLogic’s first piece of real consumer software. Every time he had attempted to tell neophytes in the past about what it was his little company really did, he had been greeted with the same blank stare and the same stated or implied question: “But what can you really do with all this 3D-graphics stuff?” And he had learned that one response in particular on his part could almost always make his interlocutors’ eyes light up with excitement: “Well, you could use it to make a flight simulator, for instance.” So, subLogic would indeed make a flight simulator for the new microcomputers. Being owned and operated by two pilots — one of them a licensed flight instructor and the other one having considerable experience in coding for flight simulators running on bigger computers — subLogic was certainly as qualified as anyone for the task.

They released a product entitled simply Flight Simulator for the Apple II in January of 1980. One can’t help but draw comparisons with Will Crowther and Don Woods’s game of Adventure at this point; like it, Flight Simulator was not only the first of its kind but would lend its name to the entire genre of games that followed in its footsteps.

Fearing that his rudimentary, goal-less simulation would quickly bore its users, Artwick at the last minute added a mode called “British Ace,” which featured guns and enemy aircraft to be shot down in an experience distinctly reminiscent of Airfight. But he soon discovered, rather to his surprise, that most people didn’t find those additional accoutrements to be the most exciting aspect of the program. They enjoyed simply flying around this tiny virtual world with its single runway and bridge and mountain — enjoyed it despite all the compromises that a host machine with six-color graphics, 32 K of memory, and a 1 MHz 8-bit CPU demanded. It turned out that a substantial portion of early microcomputer owners were to a greater or lesser degree frustrated pilots, kept from taking to the air by the costs and all of the other logistics involved with acquiring a pilot’s license and getting time behind the controls of a real airplane. They were so eager to believe in what Flight Simulator purported to be that their imaginations were able to bridge the Grand Canyon-sized gap between aspiration and reality. This would continue to be the case over the course of the many years it would take for the former to catch up to the latter.

Still, subLogic didn’t immediately go all-in for flight simulation. They released a variety of other entertainment products, from strategy games to arcade games. They even managed one big hit in the latter category, one that for a time outsold all versions of Flight Simulator: Bruce Artwick’s Night Mission Pinball was a sensation in Apple II circles upon its release in the spring of 1982, widely acknowledged as the best game of its type prior to Bill Budge’s landmark Pinball Construction Set the following year. subLogic wouldn’t release their last non-flight simulator until 1986, when an attempt to get a sports line off the ground fizzled out with subLogic Football. In the long run, though, it was indeed flight simulation that would make subLogic one of the most profitable companies in their industry, all thanks to a little software publisher known as Microsoft.

In late 1981, Microsoft came to subLogic looking to make a deal. IBM had outsourced to the former the operating system of the new IBM PC, whilst also charging them with creating or acquiring a variety of other software for the machine, including games. So, they wanted Artwick to create a “second generation” of his Flight Simulator for the IBM PC, taking full advantage of its comparatively torrid 4.77 MHz 16-bit processor.

Artwick spent a year on the project, working sixteen hours or more per day during the last quarter of that period. The program he turned in at the end of the year was both a dramatic improvement on what had come before and a remarkably complete simulation of flight for its era. Its implementation of aeronautics had now progressed to the point that a specific airplane could be said to be modeled: a Cessna 182 Skylane, a beloved staple of private and recreational aviation that was first manufactured in 1956 and has remained in production to this day. Artwick replaced the wire-frame graphics of the Apple II version with solid-filled color, replaced its single airport with more than twenty of them from the metropolitan areas of New York, Chicago, Seattle, and Los Angeles. He added weather, as well as everything you needed to fly through the thickest fog or darkest night using instruments alone; you could use radio transponders to navigate from airport to airport. You could even expect to contend with random engine failures if you were brave enough to turn that setting on. And, in a move that would have important implications in the future, Artwick also designed and implemented a coordinate system capable of encompassing the greater portion of North America, from southern Canada down to the Caribbean, although it was all just empty green space at this point outside of the four metropolitan areas.

This first Microsoft Flight Simulator was released in late 1982, and promptly became ubiquitous on a computer that was otherwise not known as much of a game machine. Many stodgy business-oriented users who wouldn’t be caught dead playing any other game seemed to believe that this one was acceptable; it was something to do with the label of “simulator,” something to do with its stately, cerebral personality. Microsoft’s own brief spasm of interest in games in general would soon peter out, such that Flight Simulator would spend half a decade or more as the only game in their entire product catalog. Yet it would consistently sell in such numbers that they would never dream of dropping it.

When the first wave of PC clones hit the market soon after Flight Simulator was released, the computer magazines took to using it as a compatibility litmus test. After all, it pushed the CPU to its absolute limit, even as its code was full of tricky optimizations that took advantage of seemingly every single quirk of IBM’s own Color Graphics Adapter. Therefore, went the logic, if a PC clone could run Flight Simulator, it could probably run just about anything written for a real IBM PC. Soon all of the clone makers were rushing to buy copies of the game, to make sure their machines could pass the stringent test it represented before they shipped them out to reviewers.

Meanwhile Artwick began to port Microsoft Flight Simulator‘s innovations into versions for most other popular computers, under the rather confusing title of Flight Simulator II. (There had never been a subLogic Flight Simulator I on most of the computers for which this Flight Simulator II was released.) Evincing at least a modest spirit of vive la différence, these versions chose to simulate a Piper Cherokee, another private-aviation mainstay, instead of the Cessna.

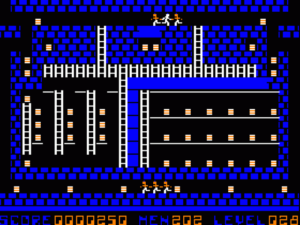

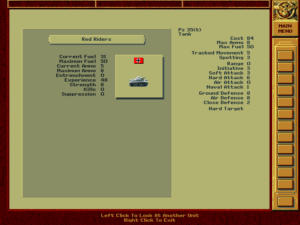

Although the inexpensive 8-bit computers for which Flight Simulator II was first released were far better suited than the IBM PC for running many types of games, this particular game was not among them. Consider the case of the Commodore 64, the heart of the mid-1980s computer-gaming market. The 64’s graphics system had been designed with 2D arcade games in mind, not 3D flight simulators; its sprites — small images that could be overlaid onto the screen and moved about quickly — were perfect for representing, say, Pac-Man in his maze, but useless in the context of a flight simulator. At the same time, the differences between an IBM PC and a Commodore 64 in overall processing throughput made themselves painfully evident. On the IBM, Flight Simulator could usually manage a relatively acceptable ten frames or so per second; on the 64, you were lucky to get two or three. “We gave it a try and did the best we could,” was Artwick’s own less-than-promising assessment of the 8-bit ports.

Nevertheless, the Commodore 64 version of Flight Simulator II is the one that I spent many hours earnestly attempting to play as a boy. Doing so entailed peering at a landscape of garish green under a sky of solid blue, struggling to derive meaning from a few jagged white lines that shifted and rearranged themselves with agonizing slowness, each frame giving way to the next with a skip and a jerk. Does that line there represent the runway I’m looking for, or is it a part of one of the handful of other landmarks the game has deigned to implement, such as the Empire State Building? It was damnably hard to know.

As many a real pilot who tried Flight Simulator II noted, a virtual Piper Cherokee was perversely more difficult to fly than the real thing, thanks to the lack of perspective provided by the crude graphics, the clunky keyboard-based controls — it was possible to use a joystick, but wasn’t really recommended because of the imprecision of the instrument — and the extreme degree of lag that came with trying to cram so much physics modeling through the narrow aperture of an 8-bit microprocessor. Let’s say you’re attempting a landing. You hit a key to move the elevators a little bit and begin your glide path, but nothing happens for several long seconds. So, getting nervous as you see the white line that you think probably represents the runway getting a bit longer, you hit the same key again, then perhaps once more for good measure. And suddenly you’re in a power dive, your view out the screen a uniform block of green. So you desperately pound the up-elevator key and cut the throttle — and ten or twenty seconds later, you find the sky filling your screen, your plane on the verge of stalling and crashing to earth tail-first. More frantic course corrections ensue. And so it continues, with you swaying and bobbling through the sky like a drunken sailor transported to the new ocean of the heavens. Who needed enemy airplanes to shoot at in the face of all these challenges? Just getting your plane up and then down again in one piece — thankfully, the simulator didn’t really care at the end of the day whether it was on a runway or not! — was an epic achievement.

Needless to say, Flight Simulator II‘s appeal is utterly lost on me today. And yet in its day the sheer will to believe, from me and hundreds of thousands of other would-be pilots like me, allowed it to soar comfortably over all of the objections raised by its practical implementation of our grand dream of flight.

At a time when books on computer games had yet to find a place on the shelves of bookstores, books on Flight Simulator became the great exception. It began in 1985, when a fellow named Charles Gulick published 40 Great Flight Simulator Adventures, a collection of setups with exciting-sounding titles — “Low Pass on the Pacific,” “Dead-Stick off San Clemente” — that required one-tenth Flight Simulator and nine-tenths committed imagination to live up to their names. Gulick became the king of the literary sub-genre he had founded, writing five more books of a similar ilk over the following years. But he was far from alone: the website Flight Sim Books has collected no less than twenty of its namesake, all published between the the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s, ranging from the hardcore likes of Realistic Commercial Flying with Flight Simulator to more whimsical fare like A Flight Simulator Odyssey. The fact that publishers kept churning them out indicates that there was a solid market for them, which in turn points to just how committed to the dream the community of virtual fliers really was.

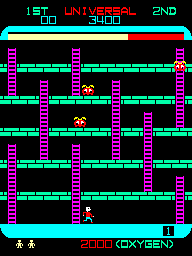

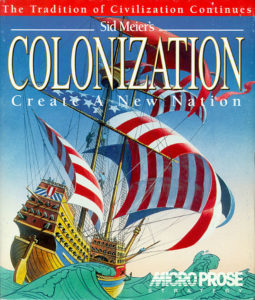

Of course, the game that called itself simply Flight Simulator was by no means the only one in the genre it had spawned. While a few companies did try to sell their own civilian flight simulators, none managed to seriously challenge the ones from subLogic. But military flight simulators were a different matter; MicroProse Software in particular made their reputation with a string of these. Often designed and programmed by Sid Meier, MicroProse’s simulators were distinguished by their willingness to sacrifice a fair amount of realism to the cause of decent frame rates and general playability, with the added attraction of enemy aircraft to shoot down and cities to bomb. (While the old “British Ace” mode did remain a part of the subLogic Flight Simulator into the late 1980s, it never felt like more than the afterthought it was.) Meier’s F-15 Strike Eagle, the most successful of all the MicroProse simulators, sold almost as well as subLogic’s products for a time; some sources claim that its total sales during the ten years after its initial release in 1984 reached 1 million units.

subLogic as well did dip a toe into military flight simulation with Jet in 1985. Programmed by one Charles Guy rather than Bruce Artwick, this F-16 and F/A-18 simulator was a bit more relaxed and a bit more traditionally game-like than the flagship product, offering air-, land-, and sea-based targets for your guns and bombs that could and did shoot back. Still, its presentation remained distinctly dry in comparison to the more gung-ho personality of the MicroProse simulators. Although reasonably successful, it never had the impact of its older civilian sibling. Instead Spectrum Holobyte’s Falcon, which debuted in 1987 for 16-bit and better machines only, took up the banner of realism-above-all-else in the realm of jet fighters — almost notoriously so, in fact: it came with a small-print spiral-bound manual of almost 300 pages, and required weeks of dedication just to learn to fly reasonably well, much less to fly into battle. And yet it too sold in the hundreds of thousands.

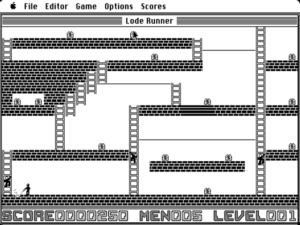

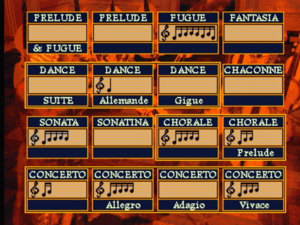

In the meantime, Artwick was continuing to plug steadily away, making his Flight Simulator slowly better. A version 2.0 of the Microsoft release, with four times as many airports to fly from and many other improvements, appeared already in 1984, soon after the 8-bit Flight Simulator II; it was then ported to the new Apple Macintosh, the only computing platform beside their own which Microsoft had chosen to officially support. When the Atari ST and Commodore Amiga appeared in 1985, sporting unprecedented audiovisual capabilities, subLogic released versions of Flight Simulator II for those machines with dazzling graphical improvements; these versions even gave you the option of flying a sleek Learjet instead of a humble single-prop airborne econobox. Version 3.0 of Microsoft Flight Simulator arrived in 1988, coming complete with the Learjet, support for the latest VGA graphics cards, and an in-game flight instructor among other enhancements.

Microsoft Flight Simulator 3.0 included the first attempt at in-program flight instruction. It would continue to appear in all subsequent releases, being slowly refined all the while, much like the simulator itself.

Betwixt and between these major releases, subLogic took advantage of Artwick’s foresight in designing a huge potential world into Flight Simulator by releasing a series of “scenery disks” to fill in all of that empty space with accurately modeled natural features and airports, along with selected other human-made landmarks. The sufficiently dedicated — i.e., those who were willing to purchase a dozen scenery disks at $20 or $30 a pop — could eventually fly all over the continental United States and beyond, exploring a virtual world larger than any other in existence at the time.

Indeed, the scenery disks added a whole new layer of interest to Flight Simulator. Taking in their sights and ferreting out all of their secrets became a game in itself, overlaid upon that of flying the airplane. It could add a much-needed sense of purpose to one’s airborne ramblings; inevitably, the books embraced this aspect with gusto, becoming in effect tour guides to the scenery disks. When they made a scenery disk for Hawaii in 1989, subLogic even saw fit to include “the very first structured scenery adventure”:

Locating the hidden jewel of the goddess Pele isn’t easy. You’ll have to find and follow an intricate set of clues scattered about the islands that, with luck, will guide you to your goal. This treasure hunt will challenge all of your flying skills, but the reward is an experience you’ll never forget!

The sales racked up by all of these products are impossible to calculate precisely, but we can say with surety that they were impressive. An interview with Artwick in the July 1985 issue of Computer Entertainment magazine states that Flight Simulator in all its versions has already surpassed 800,000 copies sold. The other piece of hard data I’ve been able to dig up is found in a Microsoft press release from December of 1995, where it’s stated that Microsoft Flight Simulator alone has sold over 3 million copies by that point. Added to that figure must be the sales of Flight Simulator II for various platforms, which must surely have been in the hundreds of thousands in their own right. And then Jet as well did reasonably well, while all of those scenery disks sold well enough that subLogic completed the planned dozen and then went still further, making special disks for Western Europe, Japan, and the aforementioned Hawaii, along with an ultra-detailed one covering San Francisco alone.

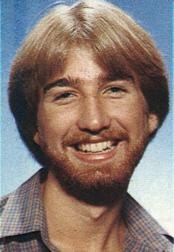

When we start with all this, and then add in the fact that subLogic remained a consistently small operation with just a handful of employees, we wind up with two founders who did very well for themselves indeed. Unsurprisingly, then, Bruce Artwick and Stu Moment, those two college friends made good, were a popular subject for magazine profiles. They were a dashing pair of young entrepreneurs, with the full complement of bachelor toys at their disposal, including a Cessna company plane which they flew to trade shows and, so they claimed, used to do modeling for their simulations. When David Hunter from the Apple II magazine Softalk visited them for a profile in January of 1983, he went so far as to compare them to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. (Sadly, he didn’t clarify which was which…)

Speed is exhilarating. Uncontrolled growth is intoxicating. As long as youth can dream, life will never move fast enough.

Whether it’s motorcycles, cars, planes, skiing, volleyball, or assembly language, Bruce Artwick likes speed. He likes Winchester disk drives, BMWs, zooming through undergraduate and graduate school in four years, and tearing down the Angeles Crest Highway on a Suzuki at a dangerous clip. The president of subLogic, Artwick is a tall, quiet, 29-year-old bachelor. He possesses a remarkable mind, which has created several of the finest programs ever to grace the Apple’s RAM.

Contrast Artwick with Stu Moment. Outgoing, of medium height, and possessed of an exceptional love of flying, Moment is subLogic’s chairman of the board. A businessman, Moment has steered the company to its present course, complementing Artwick’s superior software-engineering talents with organizational and financial skills. He’s even picked up some modest programming skills, designing a system for logging flight hours at a fair-sized flying institute.

Redford and Newman. Lewis and Clark. Laurel and Hardy. Jobs and Wozniak. Artwick and Moment. The grand adventurers riding the hard trail, living and playing at lives larger than life. It’s an old story.

When the journalists weren’t around, however, the dynamic duo’s relationship was more fractious than the public realized. Artwick wanted only to pursue the extremely profitable niche which subLogic had carved out for themselves, while Moment’s natural impulse was to expand into other areas of gaming. Most of all, though, it was likely just a case of two headstrong personalities in too close a proximity to one another, with far too much money flying through the air around them. That, alas, is also an old story.

As early as 1981, the two spent some time working out of separate offices, so badly were they treading on one another’s toes in the one. In 1984, Artwick, clearly planning for a potential future without Moment, formed his own Bruce Artwick Organization and started providing his software to subLogic, which was now solely Moment’s company, on a contract basis.

The final split didn’t happen until 1989, but when it did, it was ugly. Lawsuits flew back and forth, disputing what code and other intellectual property belonged to subLogic and what belonged to Artwick’s organization. To this day, each man prefers not to say the other’s name if he can avoid it.

This breakup marked the end of the Flight Simulator II product line — which was perhaps just as well, as the platforms on which it ran were soon to run out of rope anyway in North America. Moment tried to keep subLogic going with 1990’s Flight Assignment: Airline Transport Pilot, a simulation of big commercial aircraft, but it didn’t do well. He then mothballed the company for several years, only to try again to revive it by hiring a team to make an easier flight simulator for beginners. He sold both the company and the product to Sierra in November of 1995, and Flight Light Plus shipped three months later. It too was a failure, and the subLogic name disappeared thereafter.

It was Artwick who walked away from the breakup with the real prize, in the form of the ongoing contract with Microsoft. So, Microsoft Flight Simulator continued its evolution under his steady hand. Version 4.0 shipped in 1989, version 5.0 in 1993. Artwick himself names the latter as the entire series’s watershed moment; running on a fast computer equipped with one of the latest high-resolution Super-VGA graphics cards, it finally provided the sort of experience he’d been dreaming of when he’d written his master’s thesis on the use of bitmap 3D graphics in flight simulation all those years before. Any further audiovisual improvements from here on out were just gravy as far as he was concerned.

Such a watershed strikes me as a good place to stop today. Having so belatedly broken my silence on the subject, I’ll try to do a better job now of keeping tabs on Flight Simulator as it goes on to become the most long-lived single franchise in the history of computer gaming. (As of this writing, a new version has just been released, spanning ten dual-layer DVDs in its physical-media version, some 85 GB of data — a marked contrast indeed to that first cassette-based Flight Simulator for the 16 K TRS-80.) Before I leave you today, though, we should perhaps take one more moment to appreciate the achievements of those 1980s versions.

It’s abundantly true that they’re not anything you’re likely to want to play today; time most definitely hasn’t been kind to them. In their day, though, they had a purity, even a nobility to them that we shouldn’t allow the passage of time to erase. They gave anyone who had ever looked up at an airplane passing overhead and dreamed of being behind its controls a way to live that dream, in however imperfect a way. Although it billed itself as a hardcore simulation, Flight Simulator was in reality as much an exercise in fantasy as any other game. It let kids like me soar into the heavens as someone else, someone leading a very different sort of life. Yes, its success was a tribute to its maker Bruce Artwick, but it was also, I would argue, a tribute to everyone who persevered with it in the face of a million reasons just to give up. The people who flew Flight Simulator religiously, who bought the books and worked through a pre-flight checklist before taking off each time and somehow managed to convince themselves that the crude pixelated screen in front of them actually showed a beautiful heavenly panorama, did so out of love of the idea of flight. For them, the blue-and-green world of Flight Simulator was a wonderland of Possibility. Far be it from me to look askance upon them from my perch in their future.

(Sources: the book The Friendly Orange Glow: The Untold Story of the Rise of Cyberculture by Brian Dear and Taking Flight: History, Fundamentals, and Applications of Flight Simulation by Christopher D. Watkins and Stephen R. Marenka; Flight of December 10 1910 and March 22 1913; Softalk of January 1983; Kilobaud of October 1977; Softalk IBM of February 1983; Data Processing of April 1968; Compute!’s Gazette of January 1985; Computer Gaming World of April 1987 and September 1990; Computer Entertainment of July 1985; PC Magazine of January 1983; Illinois CS Alumni News of spring 1996; the article “High-Power Graphic Computers for Visual Simulation: A Real-Time Rendering Revolution” by Mary K. Kaiser, presented to the 1996 symposium Supercomputer Applications in Psychology; Bruce Artwick’s Masters thesis “A Versatile Computer-Generated Dynamic Flight Display”; flight-simulator product brochures from Link and Rediffusion; documents from the Sierra archive housed at the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, New York; a brochure from an exhibition on the Link Trainer at the Roberson Museum and Science Center in 2000. Online sources include a VITAL II product-demonstration video; an interview with Bruce Artwick by Robert Scoble; a panel discussion from the celebration of PLATO’s 50th anniversary at the Computer History Museum; “A Brief History of Aircraft Flight Simulation” by Kevin Moore; the books hosted at Flight Sim Books. My guiding light through this article has been Josef Havlik’s “History of Microsoft Flight Simulator.” He did at least half of the research so that I didn’t have to…)