There were two possibilities that kept those who built the PC industry in the United States and Britain awake at night, both all the more terrifying in that they seemed all but inevitable. One was the arrival of the sleeping giant that was IBM. The pioneers could easily imagine Big Blue bludgeoning its way into the industry with billions of dollars behind them and a whole slate of “standards” of its own, destroying everything they had built. This was, after all, exactly what IBM had done years before to the big mainframe market which it now all but owned for itself. When Big Blue finally came to the PC, however, it showed unprecedented eagerness to partner with already extant PC firms like Microsoft. IBM’s entrance in the fall of 1981 did eventually result in one, near universal computing standard, but the process of sweeping out what the pioneers had built would end up taking more than ten years to come to completion — and, most shockingly, neither the hardware nor the software standard that resulted would remain under IBM’s control. This gave companies, at least those able to see which way the winds were blowing, plenty of time to adapt to the new computing order. (Or, in the case of Apple, to stake out their own territory as the anti-IBM.) Yet even as IBM’s entrance proved nowhere near as bad as it might have been, everyone still waited for the other shoe to drop: Japan.

Many people who know much more about such things than I have analyzed Japan’s postwar economic miracle. Suffice to say that the devastated remains of the country after World War II rose again, and more quickly than the most optimistic could have predicted. Already in 1968 Japan became the world’s second largest economy, its explosive growth initially fueled largely by exports of steel and textiles and other heavy industry. It was at about this point that a new form of Japanese expansionism made the country again a source of concern rather than pride for the United States: a new wave of Japanese consumer products began reaching American shores, most notably consumer electronics and cars. Today we remember mostly the latter. The products of Nissan, Toyota, and Honda devastated the U.S. auto industry, and for good reason. They were cheaper, better built, better engineered, safer, and, very important in the wake of the oil crisis, much more fuel efficient than American cars of the era. Yet the American auto industry did survive in a damaged state, and in time even learned to compete again. Huge swathes of the domestic electronics industry had no such luck. Japan didn’t just damage American consumer-electronics companies, they effectively destroyed them. Already by 1982 it was getting hard to find a television or stereo made in America, and a decade later it would be, a few high-end boutique brands aside, impossible. And even as they took over the old, Japan also pioneered new technologies, such as the iPod of the early 1980s, the Sony Walkman.

In one of those fun paradoxes of capitalism, Americans fueled this expansion by buying Japanese products even as they also lived in increasing fear of this new economic menace. Television advertisements from the Detroit auto manufacturers were filled with slurs against Japan that veered uncomfortably close to unabashed racism, while newspapers and magazines were filled with awed exposés of Japanese workplace culture, which came across a bit like the Borg of Star Trek fame. The average Japanese, people were told, placed loyalty to his employer over loyalty to his family or his country; forewent hobbies, friends, vacations, and family life in favor of work; began each 12-hour-plus working day by singing company songs and doing calisthenics with his coworkers; demanded only the most modest of salaries; considered an employment contract a lifetime through-good-or-ill commitment akin to a marriage vow. Add to this the complete, threatening otherness of Japanese society, with its insular artistic culture and its famously difficult language. The long and painful recession of the early 1980s only increased the sense of dread and paranoia. An earlier generation of Japanese had been willing to fly their planes deliberately into enemy ships in the service of an obviously lost cause, for God’s sake. How could American employees compete with that kind of commitment? What industry would the Japanese be coming for next time — and was there even any point in trying to stop them when they did?

The burgeoning Western PC industry seemed like it should be right in Japan’s wheelhouse. After all, this was a country that was cranking out well-trained electrical engineers at the rate of 40,000 per year by 1982, and that increasingly enjoyed global domination of most other types of electronics. To the paranoid and the conspiracy-minded, the PC industry seemed ripe to follow the pattern set in those other sectors. Japan would let Americans do the hard work of development and innovation, and then, when the technology was mature enough to be practical for the average home and business, sweep in with an avalanche of cheap PCs to make the industry their own. This vision of Japan is of course a confused one, especially in insisting on seeing the entire Japanese economy as a single, united front; in reality it was built, like the American economy, from many individual companies who competed with one another at least as hard as they competed with the West. Still, that’s how it looked to some on the outside, especially after the arrival of Space Invaders, followed by a steady deluge of other standup arcade games, showed that Japan was no slouch when it came to computer technology.

A couple of people in the PC industry worried about a Japanese-driven apocalypse even more than most, for the very good reason that it had already happened to them once: Jack Tramiel of Commodore and, in Britain, Clive Sinclair. Both had seen their companies driven to the brink of bankruptcy in the previous decade, when low-priced Japanese models drove them out of previously profitable gigs as calculator manufacturers in a matter of months while they could only stand around wondering what had just hit them. Now, both were determined to make sure it didn’t happen to them again in their new roles as PC purveyors.

Commodore caused increasing chaos in the American PC industry of the early 1980s by selling first the VIC-20 and then the Commodore 64 at ever lower prices. Most attributed this to Tramiel’s maniacal determination to dominate at any cost, as summed up by his famous motto, “Business is war.” Yet an at least equally important source of his price-cutting mania was his fear of the Japanese, his fear that they would come in and undercut everyone else if he didn’t do it first. As he said in another of those little aphorisms he was so good at coining, “We will become the Japanese.” His competitors who cursed him as the ruthless SOB he was likely also had him to thank that the doomsday scenario of a Japanese takeover never came to pass. Japan would certainly play its role as a source for chips and other components, and companies like Epson and Okidata became huge in the printer market, but the core of the American computer industry would remain largely American for many years. With Commodore already dominating the home market with its low-priced but reasonably solid and usable machines, Japanese firms didn’t have the opportunities to upstage and undercut the competition that they did in other industries.

In a turnabout play that he must have greatly enjoyed, Tramiel actually opened his war with Japan on the enemy’s home front. Six months before introducing the VIC-20 to North America and Europe in the spring of 1981, Commodore debuted it in Japan as the VIC-1001. It became a big success there, although its limitations ultimately ensured it was a fairly short-lived one, just like in North America and Europe. Commodore would try to bring its later machines to Japan as well, but never got the same traction that it had with the VIC. Instead, Japan’s PC market remained peculiarly, stubbornly insular throughout the 1980s. If Japanese computers never invaded the West the way so many had feared, Western manufacturers also never had much luck in Japan. They were partly kept at a distance, as had been so many Westerners before them, by the challenges of the Japanese language itself.

Japanese is generally acknowledged to have the most complicated system of writing in the world. It’s comprised of three different traditional scripts, often interleaved in modern times with the occasional foreign phrase written using Latin characters. One script is kanji, a script borrowed from Chinese with thousands of characters, each of which represents a concept rather than a phonetic sound. In addition, there are two syllabaries that can be used to write the language phonetically: hiragana and katakana. Including about 50 characters each, they are simply different scripts for the same phonetic values, similar, but not quite equivalent, to upper-case and lower-case letters in Western languages. Normal Japanese text is written using all three intermixed: kanji is used for the stems of content words; hiragana for suffixes, prepositions and function words; and katakana for a variety of other tasks, most notably to write loan-words from other languages and to add emphasis to a certain point. To complete this confused picture, and as anyone who has browsed Japanese videogame boxes can attest, many Western proper names are simply written in their original form, using Latin characters.

All of this amounts to a nightmare for anyone trying to make a computer input and output Japanese. Computers have traditionally stored text using a neat arrangement of one byte per character, which gives the possibility of having up to 256 separate glyphs. That’s more than enough not only for every English character but also for the various accents, umlauts, ligatures, and the like found in many non-English Western European languages. For Japanese, however, it’s sadly inadequate. Then there’s the problem of designing a keyboard to input all those characters. And there’s an additional, more subtle problem: with so many characters, each Japanese glyph must be quite intricate in comparison to the simpler abstracts that are Latin letters, and the differences between glyphs are often quite small. The blocky displays of the early PC era were incapable of rendering such complexity in a readable way.

Faced with such challenges, which made localizing their existing designs for Japan all but impossible, most Western companies largely chose to leave the Japanese market to Japanese companies. Although the first PCs available for purchase in Japan came from Apple and Radio Shack, it didn’t take Japanese companies long to jump in and take over. Hitachi and NEC introduced the first pre-assembled PCs to be built in Japan in 1979. By 1982, Japanese manufacturers controlled 75 percent of the Japanese market, which was dominated by three machines: the NEC PC-8801, the Sharp X1, and the Fujitsu FM-7. None completely solved the fundamental problems of displaying Japanese. In addition to the standard English glyphs, each could display only katakana, chosen because its characters are square and easy to make out even on a low-resolution display, and perhaps a handful of kanji pictographs, for extremely common concepts like “date” and “time.” Katakana, on its own, is fine for short sentences or simple messages, but reading and writing longer passages in it alone is a difficult, wearisome task. The machines had to be commanded, meanwhile, in good old English-derived BASIC (usually sourced from Microsoft), a particular challenge in a country large and insular enough that a good knowledge of English, especially at this time, was a fairly rare trait.

In light of these tribulations, Japanese companies worked feverishly to develop hardware capable of storing and displaying proper Japanese writing. In 1982 NEC introduced the first machine that could do that reasonably painlessly in the form of the PC-9801, an advanced 16-bit computer built around the Intel 8086 processor. It soon ruled the Japanese business market despite being incompatible with the IBM PC that dominated business computing elsewhere. By the time it was finally discontinued in 1997, the PC-9801 line had sold well over 15 million units, virtually all within Japan. The need to display kanji characters and compete with NEC drove other manufacturers, with the happy byproduct that most Japanese computers soon had very advanced display capabilities in comparison to most Western machines.

The PC-9801 and its competitors clearly pointed the way forward for computing in Japan, but they were initially expensive machines targeted very much at business. Home users would remain stuck for at least another couple of years with their more primitive 8-bit machines built around the Zilog Z-80 or Motorola 6809. Just like in the United States, these early adopters built a distribution network for games written by amateurs and semi-amateurs, called “doujinsoft” in Japan. Again like in the United States, a common early means of distribution was through program listings printed in the enthusiast magazines. The first and most respected of these, sort of the Japanese Byte, began in 1977 and was called Monthly ASCII. In 1981 the magazine began to publish an annual supplement for April Fool’s Day, called Yearly Ah-SKI! It mostly consisted of fake articles and advertisements mocking the computer industry, but included one full, working program as well each year. The second Yearly Ah-SKI!, in 1982, hosted what was almost certainly the first text adventure, first adventure game, and first full-fledged digital ludic narrative to be published in Japan. We’ll look at that next time.

sharc

July 27, 2012 at 4:16 pm

oh hey, i was wondering if you’d ever cover japanese computing!

while i don’t know about the fujitsu or sharp machines, the pc-88 did eventually develop a solution to the kanji problem. the system was designed with slots for expansion boards, and one of the first was a dedicated rom upgrade for jis level 1 kanji. it quickly became a standard feature on the hardware, and was expanded to include jis level 2 in later iterations.

it’s still a huge pain in the ass to read the more complex characters on an 88’s display, though!

Mark

July 28, 2012 at 5:03 pm

JIm, I don’t know if you look at replies to earlier blog posts but I recently wrote a long reply on Deadline part 4 about your articles dealing with that game. Tell me what you think.

Jimmy Maher

July 28, 2012 at 7:57 pm

No need to worry about me not seeing older comments. I get an email every time someone comments anywhere on the blog, and I always read comments on older posts with equal interest. :)

Nori

September 6, 2012 at 2:50 pm

I’ve been reading this blog with much interest for some time but can you imagine how much I was surprised to find an entry about my country?

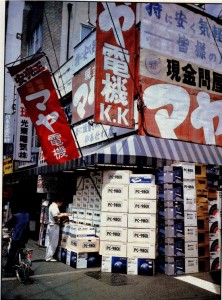

And the picture! Where did you know the store? It’s Maya Denki, the (in)famous discount electrical retailer in Akihabara. Its owner is a notorious figure who was known being a tough businessman like Jack Tramiel. Even there is a novel based on his life.

I have much to say about the article (VIC-1001 made a moderate success in Japan but not so big) but here I constrain myself to point out just one thing: the 8-bit machine’s inability to handle Japanese.

In short, we just accepted it. We all knew that handling Japanese required some machine power which cannot be expected for 8-bit. Most 8-bit machine could display Japanese characters (including some kanji) but just that. Even powerful 16-bit PC-9800 series, early models were not easy to handle Japanese in practical level. And if need word processing, there were a lot of dedicated machines for personal users.

There’s also an informative entry about Japanese input methods in Wikipedia.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kana-Kanji_conversion_system

Thanks for very interesting article.

Nori from Tokyo

Jimmy Maher

September 6, 2012 at 3:05 pm

You’re welcome!

The picture was published in Byte magazine. The author of the article took a sort of technology tour of the East, and reported on it in an article about the emerging computer industry in Asia. As I mentioned in the article, many in the American computer industry were terrified at the idea of Japan coming in and taking over. So Byte, among others, kept a close eye on developments.

Giuseppe

April 24, 2013 at 2:33 pm

One of the things that indeed shocked me when I first started learning about 80s Japanese PCs was how good their video capabilities were.

X

October 2, 2013 at 9:19 pm

Kanji are not actually pictographic. Or rather, a very small number of them are. Most Chinese characters (and by derivation, kanji) are ideophonetic. That is, they contain a marker indicating the idea or class of the character, called a “radical” and the rest of the character indicates the pronunciation of the character by association to a simpler character.

For example, 們 (men, indicating more than one person) is made up of radical 亻, which is a little man (so this character is “about people”) and 門, which is a little door (pronounced “men”). So the some of the little components are pictographic, but most of the characters aren’t.

Frustratingly enough for the Japanese, the phonetic bits only make sense if you speak (ancient) Mandarin!

On the other hand, a Japanese person could read and understand (most of) the meaning of a Chinese text without knowing how to pronounce it correctly. That’s generally more useful than an English person’s ability to (sort of) pronounce French text without having any idea what it means.

Adrian

April 19, 2019 at 1:46 am

With the caveat that I know little Japanese and it is entirely possible that the specific borrowings it has made from Chinese may reside exclusively or near-exclusively within the minority of Chinese graphs that are strictly pictographic in nature, I’d like to add to and clarify the above.

It’s more than just a case of Chinese graphs containing both phonetic and semantic information, it’s that in many cases the radical is irrelevant because the entire graph has been borrowed for a word with a completely different meaning based solely on a similar sound (or, what used to be a similar sound 2000-3000 years ago, though of course new words are formed all the time in Chinese using current pronunciations, varying with the dialect), what the 2nd-century A.D. writer Xu Shen called 假借, “borrowing”, in the first great work of Chinese etymology (interestingly, that particular compound does not appear to exist anymore in modern Standard Written Chinese).

The radical of a word – really a syllable as opposed to a word, as, though early Chinese was mostly monosyllabic, it wasn’t always, and the language has become progressively polysyllabic as the centuries have marched past – therefore does not necessarily have anything to do with the semantic meaning of that word, especially since the meaning (and indeed the pronunciation) of many words in Chinese has changed a great deal over time; in his seminal Outline of Classical Chinese Grammar, Edwin Pulleyblank states that the “great majority” of Chinese graphs are either phonetic/semantic compounds or borrowings of the type noted earlier. And while modern written Chinese attempts to ape Mandarin usage as much as possible, it still derives its written forms from those used in Classical/Literary Chinese (and indeed is incapable of rendering dialectical variances with the precision of a language that uses an alphabet and that therefore can write “you all” vs “y’all”).

And while there are some words that still maintain a written form that echoes a semantic or pictographic origin (e.g. 日 sun, 口 mouth), many of which are no doubt used in Japanese today, many (most?) of the Chinese graphs that do have a strictly pictographic origin no longer look anything like they did in the ancient past and you would have no clue, unless told by a Sinologist that it was so, that they were originally meant to represent an image of something. This is somewhat less true, in some cases, for Simplified Chinese than for Traditional (and I confess that I do not know which script the Japanese use when writing kanji), but as an example, the Oracle Bone Script (ca. 1250 B.C.) for tiger looks very much like an animal with marks for stripes and and a tail and head, etc. Here is what it looks like now (in Traditional script): 虎. Most of those scribal changes were already well underway or even completed by the time of the late Warring States-into-Qin-and-Han era.

None of which has a gosh-darned thing to do with computers, but I guess I felt the need to chime in. Love the blog, btw. It is going to take me some time to catch up to 2019’s posts, but as a longtime Infocom fan (not to mention classic gaming in general) it’s all very interesting.

Matt Ludwig

May 15, 2018 at 10:13 pm

I recently saw an episode of Computer Chronicles from the early 80s about Japanese computing, in which a Japanese electronics executive acknowledged that, aside from the language problems enumerated above, part of what kept them from breaking into the US PC market was a cultural barrier. Early PCs were viewed as being highly steeped in obscure corners of Western culture, and as such they weren’t especially confident at being able to compete at all.

Ben Finney

June 11, 2018 at 10:48 am

“[…] thousands of characters, each of represents a concept […]” — should say “[…] each of which represents […]”.

Jimmy Maher

June 11, 2018 at 11:21 am

Thanks!

Sebastian Echeverria

July 14, 2019 at 3:33 am

Awesome post, as usual.

Small typo: I think “early adapters” should be “early adopters”, right?

Jimmy Maher

July 16, 2019 at 12:53 pm

Indeed. Thanks!

Ben

July 2, 2020 at 9:25 pm

calisthetics -> calisthenics

Jimmy Maher

July 3, 2020 at 8:21 am

Thanks!

Jeff Nyman

September 20, 2021 at 10:46 am

Admittedly a sidelight to this article, but the following requires a bit of historical correction:

The pioneers could easily imagine Big Blue bludgeoning its way into the industry with billions of dollars behind them and a whole slate of “standards” of its own, destroying everything they had built. This was, after all, exactly what IBM had done years before to the big mainframe market which it now all but owned for itself.

As stated in a Fortune magazine article at the time:

“The least threatening of I.B.M.’s seven major rivals . . . has been Sperry Rand’s Univac

Division, the successor to Remington Rand’s computer activities. Few enterprises have

ever turned out so excellent a product and managed it so ineptly. Univac came in too late

with good models, and not at all with others; and its salesmanship and software were

hardly to be mentioned in the same breath with I.B.M.’s.”

That was from Gilbert Bruck in his article “The Assault on Fortress I.B.M.” from June 1964.

IBM didn’t “bludgeon” it’s way into the mainframe market. It eased in with a much better offering than its competitors who often had trouble getting out of their own way.

It’s true that by 1970, IBM had achieved an install base of over 35,000 computers and cemented an ironclad grip on between 70% and 80% of the mainframe computer market. But that was due to out-innovating.

It was back in April of 1964 that IBM announced its System 360 series of mainframe computers. And this was truly a revolutionary concept in that it unified the company’s entire product line from the extreme low end all the way up to its most powerful supercomputers. Beyond the obvious widespread compatibility that was good for its customers, the System 360 adopted a memory word length based on multiples of eight bits rather than the previous standard of six.

So it’s true that with IBM’s commanding lead in the marketplace, the 8-bit byte became the standard building block of computer memory and thus you could argue that they introduced standards but it’s much less the “bludgeoning” that is suggested here.