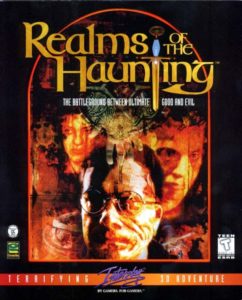

I like to imagine that Realms of the Haunting, Gremlin Interactive’s bizarre 1996 mélange of first-person shooter, point-and-click adventure, and interactive movie, was the brainchild of Ian and Nigel, students at Thomas Hughes Secondary School in Stow-on-the-Water.

Ian was sitting in a sheltered nook after school one day, sketching notes for a Call of Cthulhu scenario, when Nigel, the local football star, came barreling down the lane on his bicycle. Spotting his nerdy classmate, he dismounted in his customary way, by leaping off the still-moving bike, whose forward progress would have been arrested by Ian’s legs if he hadn’t swung them hastily aside. Nigel then joined his mode of transportation in marching up to see what Ian was up to, not without provoking some consternation from the latter, who wasn’t at all sure how this exchange was going to go. “What’cha up to, dude?”

Ian pushed his spectacles further up his nose. Even under the best of circumstances, he never quite knew how to respond to Nigel’s mix of Americanisms and Cockney, which he found almost incomprehensible at times. But he rallied. “Well, it’s sort of a scenario for a game…”

“A game? What kind of game?”

“Call of Cthulhu. It’s sort of a horror game. You get together with some mates, and one of you is sort of the referee. The others are all investigators who learn about this creepy old mystery. First they find this old bunch of letters — letters between some sort of cultist and his girlfriend…” Ian trailed off. He could sense that this was already going horribly wrong.

But it appeared that Nigel had heard only the words “horror” and “girlfriend.” “Dude, I know what you mean!” he cried. “Like Duke Nukem! You know that one? You can shoot blokes in the head with a shotgun, and the blood goes everywhere! And you meet strippers! You can pay’em to get out their titties for you.”

Ian did not know Duke Nukem. His father, a line engineer for British Telecom, was possessed of a streak of patriotism that precluded the purchase of any American personal computer. He insisted the family could get by perfectly well with their homegrown Acorn Archimedes, which advertised its stolid Britishness by means of its incompatibility with everything else. Still, Ian dearly wanted this conversation not to get onto the wrong track, so he nodded, whilst pushing his glasses up once again. “Yes… sort of…”

Any sign of hesitation was lost on Nigel. “Dude, we could work together on it!”

“Um, okay…”

“So, maybe you start in a haunted house — you’ve got to start somewhere, right? — but then it just keeps getting bigger and bigger! You find, like, one of those snakehole thingies and go to other dimensions and stuff, with wickeder and wickeder monsters to fight. And there’ll be a bunch of bosses to fight too. A bloke who’s dressed up like a doctor, like he wants to do human experimentation on you and all, and a creepy evil priest in sunglasses –”

“Wait… why sunglasses?”

“Why not?” shrugged Nigel. He was in the habit of dwelling on the abstract cool in life, not on the details.

Ian felt his blood stirring despite himself. Maybe he should think bigger for once. “Maybe you could sort of go to ancient Egypt,” he piped up cautiously. He’d always loved those ancient-archaelogy picture books his dad collected, so much so that he’d been begging for a trip to Egypt for years. “Just imagine the sort of interesting puzzles we could have around the pyramids…”

“Sure, sure, dude,” said Nigel. All things were possible in his world. “But it’s got to be bigger than that even, you know? I know… maybe in the end you’ve got to go right down into Hell and kill Satan! That would be awesome! I’m sure no one’s ever made a game where you’ve got to kill Satan.”

Again, his words set Ian thinking. They were reading Paradise Lost in his honors literature course this semester, and The Divine Comedy was waiting in the wings. And then he’d read this less respectable thing called The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail last summer. “We could sort of pull a lot of the story right out of the Bible and Milton and Dante,” he said. “Sort of build on them. Even have the Garden of Eden in there. And Knights Templar. You’ve always got to have Knights Templar.”

Nigel looked unusually pensive for a moment, so much so that Ian almost thought he was giving serious consideration to the advantages and pitfalls of building a new mythology on the scaffolding of older ones. But he was soon disabused of that notion. “We’re going to need a chick,” said Nigel contemplatively.

“Sure, alright,” said Ian. “She can be sort of your companion, who’ll know a lot more than you do about all the mythology, and can sort of help to explain…”

But again, Nigel had only caught a word or two. “Companion, what?” he leered. “I like the sound of that.”

“Say,” said Ian suddenly, “have you been in the computer lab lately?” When Nigel unsurprisingly shook his head no, he rushed on. “They’ve got this computer version of Connections there. Have you seen that one on the telly?” Another shake of the head. “It’s a show about how everything in history is interrelated –”

“Inter- what? Dude, what are you on about?”

Ian decided to elide further details. “Anyway, the point is that they put the host of the show right in the computer game. I mean, the real host. We could do the same — have real actors in the game.”

Nigel looked dubious. “How will that make it cooler?”

“Well, it would make it seem more real… sort of more believable with real people.” Nigel still looked doubtful. So Ian tried another tack. “Just think how cool all those bosses would look as real people, sort of like they’re in a real horror movie. And then to play your companion we can get a real chick,” he said, pronouncing the word as naturally as he could, like an earnest foreigner trying out his French on the natives.

Nigel was sold. “Right, then, we gotta have that too,” he said. “We’ll look like wankers if we don’t.”

And so it went. Through the sylvan afternoon, Ian and Nigel raised their castle in the air to ever loftier heights, adding battlements and wings and dungeons until the whole edifice teetered in the merest hint of a breeze. When they were finally winding down, Nigel got unexpectedly thoughtful again. “Maybe it’s a bit much,” he mused, expressing a sense of moderation which neither Ian nor any of the adults in his life had ever suspected might lurk within him. “Maybe you shouldn’t actually kill Satan after all…”

Ian nodded. They had gotten rather carried away, hadn’t they? Obviously they would have to rein things in a little. Or a lot.

“We’re gonna need some material for the sequel, right, mate?” Nigel grinned. “And anyway, we got to leave Marilyn Manson a Satan to sing about. Am I right, what?” he queried with a friendly fist jab.

Ian wasn’t sure whether he was right or not, but he could always see the wisdom in restraint; his whole life to date had been a study in it. “Okay, we have enough already without Satan. Maybe too much. But if it does get to be too much, we could always just sort of say it was all in someone’s imagination at the end, like in the last episode of St. Elsewhere.” That last reference spoke to how comfortable he was beginning to feel with his rambunctious design partner. His mother had an eccentric fondness for soapy American television which she’d imparted to her son, but normally he would die before sharing this passion with any of his peers.

Nigel was unfazed, if also uninterested. “Sure, dude. Truth.” He held out his hand for a fist bump, which Ian navigated with only a little awkwardness. It seemed they were now fast friends, but it was also time for Ian to get home for dinner; his mother did scold so when he was late. Nigel nodded his acquiescence, digging his bicycle out of the bushes where it had landed a couple of hours before. “Check you later, mate,” he said as he swung one leg over the saddle.

“Yes… mate” said Ian. “Our game’s going to be… awesome.” He smiled to himself as Nigel rode off into the sunset. He rather liked the feel of the word on his tongue.

One week later, the boys sent their design document to Gremlin Interactive.

Fair warning: this article spoils the “shocking” denouement of Realms of the Haunting as well as some other plot details.

Alas, the real origin story of Realms of the Haunting is somewhat more prosaic. The game’s individual pieces mark it as a thoroughgoing product of its time; it’s only their amalgamation in one place that makes it so bat-guano insane.

The project began when Gremlin Interactive joined three-quarters of the other games studios on the planet in beating the bushes for a DOOM-like 2.5D engine in the wake of that game’s extraordinary success. They wound up sourcing the “True3D” engine — which was actually no more true 3D than DOOM had been — from Tony Crowther, a legendary British games programmer whose career’s beginning predated Gremlin’s own 1984 founding. Crowther also offered Gremlin two ideas for a game to make with his engine. One was a “generic monster game,” as he puts it, while the other had a “devil theme.” Gremlin chose the latter. So far, so DOOM-like, in theme as well as technology.

But here’s where it starts to get weird. Gremlin, virtually alone among the many studios working with engines like this one, thought that theirs could be twisted to suit the needs of a puzzle-based adventure game instead of being strictly a vehicle for first-person carnage. And the odd thing is, they were kind of right. After production had already started on Realms of the Haunting, another team at Gremlin used the True3D engine to create a non-violent comedy adventure in the LucasArts tradition, to surprisingly good effect. Normality‘s ramshackle 2.5D visual aesthetic proved a good fit with its cock-eyed protagonist’s stoner-dude perspective on the world, while its puzzle design was as buttoned down as the rest of the affair was comfortably casual. Despite being started after Realms of the Haunting, it came out months before it in 1996. Unfortunately, it garnered few sales. One senses that, in addition to being confused by the look of the thing, gamers just didn’t quite get its jokes. Nor did it help that the market was flooded with bigger, more expensive adventures from American studios that year, the last in which the adventure genre was still widely perceived as one of the industry’s AAA standard bearers.

Through it all, the Realms project trundled on, determined to be both a kick-ass first-person shooter and a brain-tickling adventure game. Writer Paul Green wanted the story to be “epic.” And indeed, it just kept growing and growing. Then someone got the bright idea to jump on yet another indelibly mid-1990s trend: the “full-motion-video” game, incorporating clips of real actors filmed in front of green screens, which backgrounds were filled in after the fact with conventional computer graphics. Gremlin hired Bright Light Studios, an outside video-production house, to cast and carry out the shoots, then spent much time and money massaging the end results into their Frankenstein’s monster of a game. By the time it came out in Britain, about a week before the Christmas of 1996, Realms of the Haunting had spent a good two and a half years in development — one year longer than had been intended — and had become by far the most expensive game Gremlin had ever made.

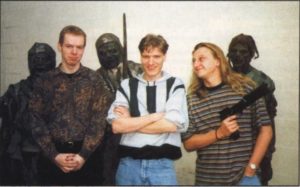

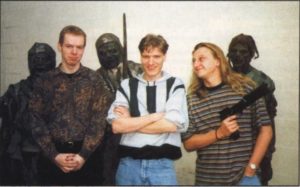

Programmer Greg Staples, engine architect Tony Crowther, and writer and designer Paul Green.

And what did they get for their money? Oh, my… where to begin? With the beginning, I suppose…

The very first impression Realms of the Haunting gives is of reaches exceeding grasps, establishing a leitmotif that will persist throughout. It opens with an epigraph that’s attributed only to “anonymous”: “Goodness reflects the light and evil bears the seed of all darkness. These are mirrors of the soul, reflections of the mind. Choose well.” This reads like pieces of other, better epigraphs cut and pasted together into a meaningless word salad. Yet it actually serves its purpose of being a harbinger of what is to come in two separate ways. Realms of the Haunting itself will play like chunks of other, better games cut and pasted together. And everyone you meet in the game will talk just like that epigraph is written.

Next we have the bravura eight-minute opening movie, in which we meet our protagonist Adam Randall, in the back of a taxi on his way to answer a mysterious summons to a deserted house out in the middle of nowhere — a visit he’s decided to make in the middle of a dark and stormy night, of course, as you do in these situations. When I first heard Adam speak, I thought it strange that Gremlin had opted to cast an American actor in the role, given that the actual text of the script shows every indication he ought to be British; the summons to the haunted house came from a self-purported colleague of his recently deceased father, who we’re told was “the pastor in a Cornish village.” But then I started noticing oddities in Adam’s vowels and in his “Ts” that didn’t fit with an American accent either. In the end, I decided he must be Canadian. (Hey, at least that puts him inside the Commonwealth!) But then, after I was finished with the game, I watched Gremlin’s short “making of” video, and all became clear: the actor was a Brit putting on an American accent. But… why, especially when it doesn’t make any sense in the context of the plot? I can only conclude that Gremlin believed they’d have a better chance of cracking the all-important American market with an American-sounding protagonist — plot fidelity be damned. Anyway, not much else about the plot will wind up making much sense. Why should this?

The actor in question is one David Tuomi, who has managed the neat trick of leaving no digital footprint whatsoever in all the years since. It’s as if he was immaculately created just to play Adam Randall, then returned to the dust from which he had been made as soon as shooting wrapped. To this day, his profile on The Internet Movie Database has exactly one entry: Realms of the Haunting. He doesn’t even enjoy the cult celebrity of someone like Dean Erickson, whose acting résumé is almost as scanty and similar long-abandoned, but who still pops up to give an interview from time to time about that one time he got to play Gabriel Knight. No, David Tuomi is just… gone. It seems he took his right to be forgotten seriously.

This is made still weirder by the fact that he really isn’t that bad here. He may not be Laurence Olivier, but he’s a good-looking, likable young man who doesn’t palpitate with nervousness when he speaks his lines, which puts him well ahead of Dean Erickson and many of his other peers in the full-motion-video field. The problems with this game’s storytelling aren’t down to him.

In fact, for all of its haunted-house clichés, the opening movie as a whole strikes a pensive note that raises the hopes of a writerly type like me. The Adam we meet in the back of that taxi is haunted by metaphorical rather than literal demons; he’s filled with regrets about all of the things he never said to his father, all of the times he could have picked up the phone to call him but didn’t. This sense of guilt is joined by other, bitterer sentiments: “He was well-liked. Had time for everyone. Except his son.” (Those might just be the most cogent lines in a script with very few of them.) You can almost begin to believe that, like all the best classic horror, this story will really be about the fears and worries and secret shames that are part and parcel of being a human being, those occasional dark nights of the soul that keep even those of us who don’t believe in ghosts wide awake from time to time. But never fear, would-be demon blasters: the game will never strike a note like this one again, and Adam will never again betray any sign of having an inner life that goes beyond the exigencies of the moment.

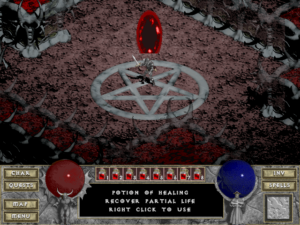

Adam pays the taxi driver and enters the house. As he does so, the doors shut behind him with a crash, like the sealing of a tomb. He doesn’t so much as twitch in response to this event. On the one hand, this is a typical discordance of these sorts of productions: the David Tuomi acting in front of a green screen had no slamming doors to react to, because both the sight and the sound of them were painted in later. But it also establishes a precedent in another way. Adam will stumble through everything to come comically unfazed by it all. Even now, at the outset, he just shrugs as he wanders the corridors of a house with glowing pentagrams splashed over the walls and doors, portraits that blink at him with livid red eyes, a fly-encrusted suit of armor that appears to contain a human corpse, decapitated animal bodies strewn randomly about the place, and a typewriter that’s typing “We live!” over and over again of its own accord. Unflappable doesn’t begin to describe this guy. “A rat. No head,” he mutters to himself, and moves on. In the case of the typewriter, he confines his observations to, “Ink ribbon’s missing.” Right. Better buy a new one in the morning, once I’m through with all this tedious business of demon blasting. Which Adam will soon be doing with laconic aplomb, mowing through his enemies like Duke Nukem — until it’s time for a cut scene, at which point he reverts to being the slim, harmless-looking guy we met in the taxi.

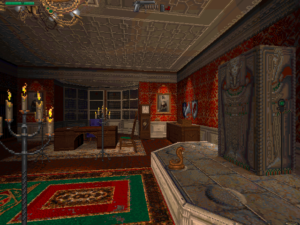

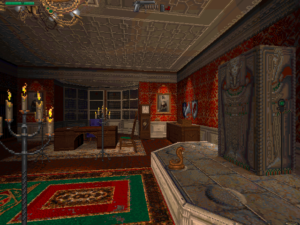

Could this library look any more Lovecraftian?

The aforementioned demons show up only after you’ve solved a puzzle or two and found your way into the house’s library, that natural repository of secrets. In the best tradition of a Call of Cthulhu scenario, you find a clutch of 70-year-old letters between a cultist and his paramour, talking about some ominous ritual they’re attempting to enact. And, even more disconcertingly, you meet Adam’s father’s ghost, entwined in chains that make him look like a parody of Jacob Marley in A Christmas Carol.

Then you open the inevitable secret door that’s hidden behind the bookcase, and the first demon comes running at you. With head-snapping speed, we’ve gone from pensive psychological horror to Gothic horror to a vaguely Lovecraftian story to a B-grade zombie flick.

And so it will go for the next couple of dozen hours. The designers’ response to any and all suggestions seems to have been, “Sure! Put it in there!” Realms of the Haunting is a study in excess, a game that wants so very badly to be all things to all people, evincing all of the sweaty desperation in pursuit of that goal that Adam so noticeably fails to display. It just goes on and on and on and on. Most games that tell pre-scripted, set-piece stories have around four or five chapters; this one has twenty.

Sometimes, however, less is more. Perhaps more so than any other game I’ve played, Realms of the Haunting descends linearly in quality — in all measures of quality, from writing to production values to gameplay — as it unspools from beginning to end.

That said, the descent doesn’t happen at the same pace along these different vectors. It’s the story that goes off the rails first. The central problem here is all too typical in videogames: stakes inflation. It’s not enough for this to be a tale of a father and son’s sins and redemption, not even enough for the fate of a family or a town or even a nation to hinge on Adam’s actions. No, the fate of the entire world — no, make that the fate of the entire universe! — has to be borne on the fashionably padded shoulders of Adam Randall.

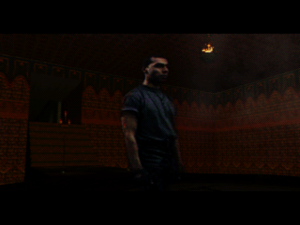

The flames of Hell are so bright, Florentine’s got to wear shades.

It soon becomes clear that Paul Green has no idea how storytelling works at the most fundamental level. Instead of giving us one central villain to hate, he dilutes the impact with a whole rogue’s gallery of weirdos whose relationships to one another are almost impossible to keep track of: the creepy priest who seems to have been modeled on Rasputin, the guy who runs around in a doctor’s outfit, the guy dressed up like he’s auditioning for a Sam Spade flick who’s always flipping through a deck of cards and giggling like a low-rent Joker. If this was a Nintendo-style level-based videogame, these folks might work as a series of bosses. But as an interactive story told primarily through about 90 minutes of live-action video, it never gives anybody enough screen time to make you care. It’s not a problem of the acting; like David Tuomi, all of the actors perform what’s being asked of them serviceably enough, intoning their lines like the Shakespearean creatures of the British theater scene they probably were. It’s a problem of the writing.

Your allies are no better. Again, there’s just too many angels and archangels and God knows what else running around, all talking in symbolic gibberish that brings to mind the game’s horrid opening “quotation” and never telling you what you actually want to know. At one point, one of them apologizes for “speaking in metaphors” — which is hilarious because absolutely everybody in this game speaks in nothing but metaphors, and terrible mixed ones at that, until you want to pull out your big old shotgun, point it at their foreheads, and demand a straight fricking answer, for once. The would-be drama has a way of shooting its gravitas in the foot at every turn. Your guardian angel Hawk, for example, runs around in an artfully crumpled tee-shirt that makes him look like a model in a Gap circular. Another character, one who has something or other to do with the Knights Templar, is named “Aelf” — pronounced as far as I can tell just like “Alf,” which always sets me giggling to myself about cat-loving anthropomorphic aliens.

The character you spend the most time with is Rebecca, a fetching lass in a chic pantsuit more appropriate for a day behind a desk in the City than a night in a haunted house. (She’s played by one Emma Powell, who unlike David Tuomi went on to a long and fruitful career as a supporting and voice actress in movies, television, and videogames.) Our avatar of indifference Adam comes across her in the library at the end of Chapter 2, inexplicably just sitting there, and, true to form, never bothers to ask her how she ended up there. For the bulk of the game thereafter, she serves as his sounding board and advisor as he wanders about, offering hints and commentary on the environment and adding a little spark of life to what would otherwise be a decidedly lonely experience. In that sense, she’s not a bad addition at all.

Emma Powell and David Tuomi

Indeed, the gameplay generally declines less precipitously than the writing — with one caveat. That comes in form of the interface, which will first flabbergast you with its inscrutability and then annoy you like a dull foot ache for all the hours to come. Some of this game’s confusions for the modern player exist in many first-person shooters that came out between 1993 and 1998, including to some extent even (un-modded) DOOM itself. These were the years before the control schemes that have been the standard for the last quarter-century had quite stabilized.

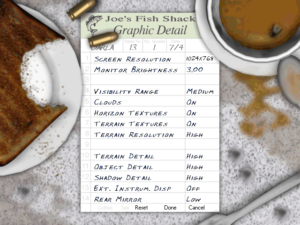

Still, Realms of the Haunting‘s problems in this department extend well beyond the lack of mouse-look or the unfamiliar default key mappings. The adventuring interface is fiddly almost beyond belief; everything you try to do is ten times harder than it would be if you were doing it in real life. Using or examining an object entails pressing “I” to bring up the inventory screen, then finding its stamp-sized icon among the four separately sorted categories of junk you’re carrying: “general items,” “weapons,” “mysterious or magical items,” or “documents.” (No, it isn’t always immediately obvious what the game considers to belong in what category.) For some reason, all of this is allowed to fill no more than a quarter of the screen. So, if it’s a document you’re interested in reading, you get to do so by dragging it around inside a small window; it’s like reading a book through a telescope. If you want to try to use an object on something in the world, you first have to place it in Adam’s left hand — his left hand, mind you; the right is reserved for weapons — then exit the inventory system completely before you can click on the target. This is so annoyingly convoluted a process that I’m going to tarnish my cred as a hardcore adventurer by strongly suggesting that you play this game, if you choose to do so, in “easy” adventuring mode, where it automatically uses the correct object in the correct place, as long as you have it in your inventory. What’s truly bizarre about all this is that Normality, the other Gremlin game that was built with the True3D engine, has a fast, elegant popup radial menu for examining and using objects. What on earth were these developers thinking?

You can almost always tell whether the makers of any given game have given it to anyone to actually play before they released it. These ones most definitively did not, as evidenced by the constant unnecessary niggles. When you find a new key, for example, you never know where it will appear among the twenty others you’re already carrying around with you. Why not dispose of the ones that have already served their purpose?

Still, if you can get past the torturous interface, the first chapters, when you’re still exploring the house itself, acquit themselves fairly well. The shooting parts serve their purpose well enough, while the puzzling parts can be surprisingly satisfying, revolving mostly around finding keys that let you open up more and more of the house for exploration. Realms of the Haunting is at its best at this stage, just about making you believe that its chocolate-and-peanut-butter combination of genres has something to recommend it after all. And, while I would by no means call it scary in a “I don’t want to play this alone” kind of way, its aesthetic does qualify as enjoyably creepy.

It’s only after you leave the house to start dimension-hopping about seven chapters in that things begin to fall apart on the gameplay front as well. An engine that can portray shadowy hallways to fairly good effect is less suited to conveying the splendor of ancient Egypt, the beauty of the Garden of Eden (yes, you really do travel there), or the horrors of Hell (yes, you really do travel there as well). All of these environments are much bigger, sprawling places than the house, with unfortunately less inside of them to see and do, a sure sign that constraints of budget and time were catching up with the designers’ ambitions. Even the normal spaces become hard to find your way around in; you are provided with helpful maps of most of them, but consulting them involves scrolling them around in that absurd little inventory window, a process so excruciating that you won’t want to bother until you’re truly at wit’s end. And then there are the deliberate mazes… oh, Lord, save us from the mazes in this game, which are scarier than any of its demons. There are three of them, extended, hair-pulling monstrosities all.

The game gives you maps of most of the larger areas, which is very kind and progressive of it. But then it makes you peer at them through a pointlessly tiny window. And every time you bring a map up again, it resets the view to the top left. The cruel irony here is that the full document seems very close to the size of your monitor screen. This is not rocket science, Gremlin.

As the game wears on, the puzzles become increasingly surreal, to say the least. For example, you run through one of the mazes collecting little brains to shove into a giant brain machine, apropos of nothing that comes before or after. And you’ll spend an inordinate amount of time constructing a bong so one of the angelic beings you meet can toke up properly. (I assume that all of the obvious jokes about what the folks at Gremlin were doing when they made this game have already been told, so I won’t bother.) If you’ve made it this far without ragequitting, you must long since have adopted Adam’s attitude. Just shrug your shoulders and go with it.

It gradually becomes clear that significant chunks of the story are simply missing in action, presumably due to budget shortfalls or space limitations; Realms of the Haunting shipped on four CDs as it was. At one point, Adam and Rebecca stand on the verge of a dramatic showdown with one of the ceaselessly rotating lazy Susan of villains. After everyone has engaged in the usual speechifying that precedes such things, the screen fades to black, a scream sounds, and you flex your mouse hand and get ready for battle… and suddenly Adam is in a prison cell, while Rebecca has somehow escaped and is trying to rescue him from outside the door. The game never explains how any of this happened. Just go with it.

At long last, you get to the very end and save the universe/multiverse/whatever. And then… you join a straitjacketed Adam in a mental hospital, as he finishes telling his tale to a skeptical doctor and a nurse with a syringe at the ready. Oh, my. You can almost hear the writers slapping one another on the back for being so clever. At least now we know why one of the villains was dressed up like a doctor. And perhaps, come to think of it, why we’ve never heard another peep from David Tuomi…

The dominant impression Realms of the Haunting leaves you with is that of bits that don’t fit together. This applies as much at the most granular levels of detail — as in the way that Adam’s reactions never quite seem to be in line with what is actually happening to him — as it is in the big picture. Rebecca, for instance, shows up in the movie bits, and is on-hand to offer commentary in the adventure-game bits, but simply doesn’t exist in the shooter bits. Likewise, we never see the veritable Fort Knox of weaponry Adam is carrying around with him when we see David Tuomi portraying him in the movie bits. Of course, Realms of the Haunting is hardly the first or the last game to hand-wave away inconvenient details like these. If it succeeded on at least one of its three levels — whether as a shooter, a puzzle-driven adventure game, or a well-scripted interactive movie — I’d be more inclined to overlook such inconsistencies. As it is, though, it’s failing everywhere by the time you make it halfway through: the shooter bits have become samey and janky, the adventure bits samey and illogical, the story samey and flat-out incomprehensible. This game is the inversion of the reviewer’s cliché about the creation under review being “more than the sum of its parts.” As bad as these parts are, the whole manages to be less than their sum. Every part of the game actively diminishes every other part.

And yet as hot messes go, this one is as intriguing as they come. Whatever else you can say about Realms of the Haunting, there’s never been another game like it. It’s amazing to think that a purportedly responsible management team ever approved such an outlandish monstrosity as this one. In fact, there’s a melancholy aspect to that: long shot that it was to get made even in 1996, it’s even harder to imagine this game appearing any later in the decade. For as gaming moved into the last third of the 1990s, genres were calcifying into fixed categories with inviolate sets of expectations. Soon absolutely no one would be taking fliers on crazy cross-genre experiments like this one anymore.

To know why, we need only look to Realms of the Haunting‘s commercial performance. Its British release date was not ideal, coming too late to reap the proper benefit of the Christmas buying season. And the circumstances of its American release, in the dog days of March of 1997 under the imprint of an unenthusiastic Interplay Entertainment, were no more auspicious. Yet a game with true mass appeal can overcome such factors — as, for example, Diablo did when it was shipped to American stores between the Christmas and New Years of 1996. Unfortunately, Realms of the Haunting was the antithesis of Diablo, being as clunky, fiddly, and scattered as Blizzard’s juggernaut was frictionless, polished, and laser-targeted. As Computer Gaming World put it in an (overly) generous 4.5 star review, Gremlin’s game had natural appeal to “action gamers looking for some adventure” and “adventure gamers looking for some action.” But just how many people meeting these descriptions were there? Not very many at all, it would appear. Realms of the Haunting was dead on arrival, selling less than 500 units in its first week on the market in Britain. Its high cost combined with its abject commercial failure had much to do with Gremlin’s subsequent collapse, which resulted in the company being bought out by the burgeoning French giant Infogrames in 1999.

Even today, however, some of the delusions of grandeur that allowed this game to be made still persist. Steve McKevitt, Gremlin’s former communications chief, blames its failure on “a backlash against full-motion video.” He claims that the developers “got just about everything right: the script, subject matter, story line, pacing. It was years ahead of its time. More The Last of Us than Quake.” Uh, no, Steve. Just no.

Yet, easy though it is to make fun of, Realms of the Haunting is a hard game to totally hate. It’s just so earnest in pursuit of its lofty ambitions, so fixated on being epic, man. How can you hate something that’s trying this hard to be the best game ever? Chalk it up as a last artifact of an older games industry that frequently had more vision than competence, of a time when budgets were small enough to take a chance on something crazy and just see what happened. In the years to come, both of those equations would be reversed. The result would be tighter, more polished experiences, but very few games that dared to throw out all the rules, whether wisely or unwisely. Instead of logical shorthands to bracket discussions, genres would begin to look like the straitjacket Adam Randall is wearing when we catch our last glimpse of him.

And it’s for that reason really that I’ve chosen to write about this game, even though I’m not at all in the habit of writing about bad games that didn’t sell well and didn’t have much influence on the field. There’s something kind of beautiful about Realms of the Haunting‘s passionate incompetence. I’m not usually an adherent of the “so bad it’s good” school of criticism, but I can almost make an exception in the case of this game. Many critics before me have argued that it would have been a far better game if it had been content to stay inside the haunted mansion and leave off with the apocalyptic fever dreams. They’re almost certainly right, but at the same time I’m not sure I would be talking about it today had anyone involved with it understood the virtues of restraint. Realms of the Haunting is a final holdover from a messier, more freewheeling time, when everyone was still making it all up as they went along. And so, having paid our last respects to the old ways, we can now march onward, into a future that could never give us anything as amateurish, ill-considered, excessive, and lovable as this.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

(Sources: the book A Gremlin in the Works by Mark James Hardisty; Retro Gamer 24 and 108; Computer Gaming World of January 1997 and May 1997; Edge of July 1996; PC Format of December 1996; PC Power of December 1996. Online sources include Sascha Kimmel’s Realms of the Haunting fan site, Jdanddiet’s interview with the aforementioned Sascha Kimmel, Retro Video Gamer‘s interview with Tony Crowther, and a retrospective of the game at The Genesis Temple.

Realms of the Haunting is available as a digital download from GOG.com.)