As you would imagine, a lot of the things you can do in a comedy game just don’t work when trying to remain serious. You can’t cover up a bad puzzle with a funny line of self-referential dialog. Er, not that I ever did that. But anyway, it was also a challenge to maintain the tone and some semblance of a dramatic arc. Another challenge was cultural — we were trying to build this game in an environment where everyone else was building funny games, telling jokes, and being pretty outlandish. It was like trying to cram for a physics final during a dorm party. It would have been a lot easier to join the party.

— Sean Clark, fifth (and last) project lead on The Dig

On October 17, 1989, the senior staff of LucasArts[1]LucasArts was known as Lucasfilm Games until the summer of 1992. To avoid confusion, I use the name “LucasArts” throughout this article. assembled in the Main House of Skywalker Ranch for one of their regular planning meetings. In the course of proceedings, Noah Falstein, a designer and programmer who had been with the studio almost from the beginning, learned that he was to be given stewardship of an exciting new project called The Dig, born from an idea for an adventure game that had been presented to LucasArts by none other than Steven Spielberg. Soon after that bit of business was taken care of, remembers Falstein, “we felt the room start to shake — not too unusual, we’d been through many earthquakes in California — but then suddenly it got much stronger, and we started to hear someone scream, and some glass crash to the floor somewhere, and most of us dived under the mahogany conference table to ride it out.” It was the Loma Prieta Earthquake, which would kill 63 people, seriously injure another 400, and do untold amounts of property damage all around Northern California.

Perhaps Falstein and his colleagues should have taken it as an omen. The Dig would turn into a slow-motion fiasco that crushed experienced game developers under its weight with the same assiduity with which the earthquake collapsed Oakland’s Nimitz Freeway. When a finished version of the game finally appeared on store shelves in late 1995, one rather ungenerous question would be hard to avoid asking: it took you six years to make this?

In order to tell the full story of The Dig, the most famously troubled project in the history of LucasArts, we have to wind the clock back yet further: all the way back to the mid-1980s, when Steven Spielberg was flying high on the strength of blockbusters like Raiders of the Lost Ark and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. During this period, many years before the advent of Prestige TV, Spielberg approached NBC with a proposal for a new anthology series named Amazing Stories, after the pulp magazine that had been such an incubator of printed science fiction in the 1930s and 1940s. He would direct the occasional episode himself, he promised, but would mostly just throw out outlines which could be turned into reality by other screenwriters and directors. Among those willing to direct episodes were some of the most respected filmmakers in Hollywood: people like Martin Scorsese, Irvin Kershner, Robert Zemeckis, and Clint Eastwood. Naturally, NBC was all over it; nowhere else on the television of the 1980s could you hope to see a roster of big-screen talent anything like that. The new series debuted with much hype on September 29, 1985.

But somehow it just never came together for Amazing Stories; right from the first episodes, the dominant reaction from both critics and the public was one of vague disappointment. Part of the problem was each episode’s running time of just half an hour, or 22 minutes once commercials and credits were factored in; there wasn’t much scope for story or character development in that paltry span of time. But another, even bigger problem was that what story and characters were there weren’t often all that interesting or original. Spielberg kept his promise to serve as the show’s idea man, personally providing the genesis of some 80 percent of the 45 episodes that were completed, but the outlines he tossed off were too often retreads of things that others had already done better. When he had an idea he really liked — such as the one about a group of miniature aliens who help the residents of an earthbound apartment block with their very earthbound problems — he tended to shop it elsewhere. The aforementioned idea, for example, led to the film Batteries Not Included.

The episode idea that would become the computer game The Dig after many torturous twists and turns was less original than that one. It involved a team of futuristic archaeologists digging in the ruins of what the audience would be led to assume was a lost alien civilization. Until, that is, the final shot set up the big reveal: the strange statue the archaeologists had been uncovering would be shown to be Mickey Mouse, while the enormous building behind it was the Sleeping Beauty Castle. They were digging at Disneyland, right here on Planet Earth!

The problem here was that we had seen all of this before, most notably at the end of Planet of the Apes, whose own climax had come when its own trio of astronauts stranded on its own apparently alien world had discovered the Statue of Liberty half-buried in the sand. Thus it was no great loss to posterity when this particular idea was judged too expensive for Amazing Stories to produce. But the core concept of archaeology in the future got stuck in Spielberg’s craw, to be trotted out again later in a very different context.

In the meantime, the show’s ratings were falling off quickly. As soon as the initial contract for two seasons had been fulfilled, Amazing Stories quietly disappeared from the airwaves. It became an object lesson that nothing is guaranteed in commercial media, not even Steven Spielberg’s Midas touch.

Fast-forward a couple of years, to when Spielberg was in the post-production phase of his latest cinematic blockbuster, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, which he was making in partnership with his good friend George Lucas. Noah Falstein of the latter’s very own games studio had been drafted to design an adventure game of the movie. Despite his lack of a games studio of his own, Spielberg was ironically far more personally interested in computer games than Lucas; he followed Falstein’s project quite closely, to the point of serving as a sort of unofficial beta tester. Even after the movie and game were released, Spielberg would ring up LucasArts from time to time to beg for hints for their other adventures, or sometimes just to shoot the breeze; he was clearly intrigued by the rapidly evolving world of interactive media. During one of these conversations, he said he had a concept whose origins dated back to Amazing Stories, one which he believed might work well as a game. And then he asked if he could bring it over to Skywalker Ranch. He didn’t have to ask twice.

The story that Spielberg outlined retained futuristic archaeology as its core motif, but wisely abandoned the clichéd reveal of Mickey Mouse. Instead the archaeologists would be on an actual alien planet, discovering impossibly advanced technology in what Spielberg conceived as an homage to the 1950s science-fiction classic Forbidden Planet. Over time, the individual archaeologists would come to distrust and eventually go to war with one another; this part of the plot hearkened back to another film that Spielberg loved, the classic Western The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Over to you, Noah Falstein — after the unpleasant business of the earthquake was behind everybody, that is.

The offices of LucasArts were filled with young men who had grown up worshiping at the shrines of Star Wars and Indiana Jones, and who now found themselves in the completely unexpected position of going to work every day at Skywalker Ranch, surrounded by the memorabilia of their gods and sometimes by the deities themselves. Their stories of divine contact are always entertaining, not least for the way that they tend to sound more like a plot from one of Spielberg’s films than any plausible reality; surely ordinary middle-class kids in the real world don’t just stumble into a job working for the mastermind of Star Wars, do they? Well, it turns out that in some cases they do. Dave Grossman, an aspiring LucasArts game designer at the time, was present at a follow-up meeting with Spielberg that also included Lucas, Falstein, and game designer Ron Gilbert of Maniac Mansion and Monkey Island fame. His account so magnificently captures what it was like to be a starstruck youngster in those circumstances that I want to quote it in full here.

The Main House at Skywalker is a pretty swanky place, and the meeting is in a boardroom with a table the size of a railroad car, made of oak or mahogany or some other sort of expensive wood. I’m a fidgety young kid with clothes that come pre-wrinkled, and this room makes me feel about as out of place as a cigarette butt in a soufflé. I’m a little on edge just being in here.

Then George and Steven show up and we all say hello. Now, I’ve been playing it cool like it’s no big deal, and I know they’re just people who sneeze and drop forks like everybody else, but… it’s Lucas and Spielberg! These guys are famous and powerful and rich and, although they don’t act like any of those things, I’m totally intimidated. (I should mention that although I’ve been working for George for a year or so at this point, this is only the second time I’ve met him.) I realize I’m really fairly nervous now.

George and Steven chit-chat with each other for a little bit. They’ve been friends a long time and it shows. George seems particularly excited to tell Steven about his new car, an Acura I think – they’re not even available to the public yet, but he’s managed to get the first one off the boat, and it’s parked conspicuously right in front of the building.

Pretty soon they start talking about ideas for The Dig, and they are Rapid-Fire Machine Guns of Creativity. Clearly they do this a lot. It’s all very high-concept and all over the map, and I have no idea how we’re going to make any of it into a game, but that’s kind of what brainstorming sessions are all about. Ron and Noah offer up a few thoughts. I have a few myself, but somehow I don’t feel worthy enough to break in with them. So I sit and listen, and gradually my nervousness is joined by embarrassment that I’m not saying anything.

A snack has been provided for the gathering, some sort of crumbly carbohydrate item, corn bread, if I remember correctly. So I take a piece – I’m kind of hungry, and it gives me something to do with my hands. I take a bite. Normally, the food at Skywalker Ranch is absolutely amazing, but this particular corn bread has been made extra dry. Chalk dry. My mouth is already parched from being nervous, so it takes me a while before I’m able to swallow the bite, and as I chomp and smack at it I’m sure I’m making more noise than a dozen weasels in a paper bag, even though everyone pretends not to notice. There are drinks in the room, but they have been placed out of the way, approximately a quarter-mile from where we’re sitting, and I can’t get up to get one without disrupting everything, and I’m sure by now George and Steven are wondering why I’m in the meeting in the first place.

I want to abandon the corn bread, but it’s begun falling apart, and I can’t put it down on my tiny napkin without making a huge mess. So I eat the whole piece. It takes about twenty minutes. I myself am covered with tiny crumbs, but at least there aren’t any on the gorgeous table.

By now the stakes are quite high. Because I’ve been quiet so long, the mere fact of my speaking up will be a noteworthy event, and anything I say has to measure up to that noteworthiness. You can’t break a long silence with a throwaway comment, it has to be a weighty, breathtaking observation that causes each person in the room to re-examine himself in its light. While I’m waiting for a thought that good, more time goes by and raises the bar even higher. I spend the rest of the meeting in a state of near-total paralysis, trying to figure out how I can get out of the room without anyone noticing, or, better yet, how I can go back in time and arrange not to be there in the first place.

So, yes, I did technically get to meet Steven Spielberg face-to-face once while we were working on The Dig. I actually talked to him later on, when he called to get hints on one of our other games (I think it was Day of the Tentacle), which he was playing with his son. (One of the lesser-known perks of being a famous filmmaker is that you can talk directly to the game designers for hints instead of calling the hint line.) Nice guy.

The broader world of computer gaming’s reaction to Spielberg’s involvement in The Dig would parallel the behavior of Dave Grossman at this meeting. At the same time that some bold industry scribes were beginning to call games a more exciting medium than cinema, destined for even more popularity thanks to the special sauce of interactivity, the press that surrounded The Dig would point out with merciless clarity just how shallow their bravado was, how deep gaming’s inferiority complex really ran: Spielberg’s name was guaranteed to show up in the first paragraph of every advertisement, preview, or, eventually, review. “Steven Spielberg is deigning to show an interest in little old us!” ran the implicit message.

It must be said that the hype was somewhat out of proportion to his actual contribution. After providing the initial idea for the game — an idea that would be transformed beyond all recognition by the time the game was released — Spielberg continued to make himself available for occasional consultations; he met with Falstein and his colleagues for four brainstorming sessions, two of which also included his buddy George Lucas, over the course of about eighteen months. (Thanks no doubt to the prompting of his friend, Lucas’s own involvement with The Dig was as hands-on as he ever got with one of his games studio’s creations.) Yet it’s rather less clear whether these conversations were of much real, practical use to the developers down in the trenches. Neither Spielberg nor Lucas was, to state the obvious, a game designer, and thus they tended to focus on things that might yield watchable movies but were less helpful for making a playable game. Noah Falstein soon discovered that heading a project which involved two such high-profile figures was a less enviable role than he had envisioned it to be; he has since circumspectly described a project where “everyone wanted to put their two cents in, and that can be extremely hard to manage.”

In his quest for a game that could be implemented within the strictures of SCUMM, LucasArts’s in-house point-and-click adventure engine, Falstein whittled away at Spielberg’s idea of two teams of archaeologists who enter into open war with one another. His final design document, last updated on January 30, 1991, takes place in “the future, nearly 80 years since the McKillip Drive made faster-than-light travel a possibility, and only 50 years since the first star colonies were founded.” In another nod back to Spielberg’s old Amazing Stories outline that got the ball rolling, an unmanned probe has recently discovered an immense statue towering amidst other alien ruins on the surface of a heretofore unexplored planet; in a nod to the most famous poem by Percy Shelley, the planet has been named Ozymandias. Three humans have now come to Ozymandias to investigate the probe’s findings — but they’re no longer proper archaeologists, only opportunistic treasure hunters, led by a sketchy character named Major Tom (presumably a nod to David Bowie). The player can choose either of Major Tom’s two subordinates as her avatar.

A series of unfortunate events ensues shortly after the humans make their landing, over the course of which Major Tom is killed and their spaceship damaged beyond any obvious possibility of repair. The two survivors have an argument and go their separate ways, but in this version of the script theirs is a cold rather than a hot war. As the game goes on, the player discovers that a primitive race of aliens living amidst the ruins are in fact the descendants of far more advanced ancestors, who long ago destroyed their civilization and almost wiped out their entire species with internecine germ warfare. But, the player goes on to learn, there are survivors of both factions who fought the apocalyptic final war suspended in cryogenic sleep beneath the surface of the planet. Her ultimate goal becomes to awaken these survivors and negotiate a peace between them, both because it’s simply the right thing to do and because these aliens should have the knowledge and tools she needs to repair her damaged spaceship.

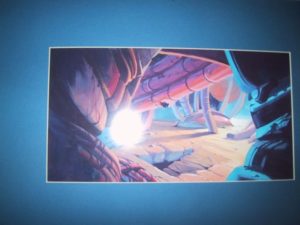

This image by Ken Macklin is one of the few pieces of concept art to have survived from Noah Falstein’s version of The Dig.

For better or for worse, this pared-down but still ambitious vision for The Dig never developed much beyond that final design document and a considerable amount of accompanying concept art. “There was a little bit of SCUMM programming done on one of the more interesting puzzles, but not much [more],” says Falstein. He was pulled off the project very early in 1991, assigned instead to help Hal Barwood with Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. And when this, his second Indiana Jones game, was finished, he was laid off despite a long and largely exemplary track record.

Meanwhile The Dig spent a year or more in limbo, until it was passed to Brian Moriarty, the writer and designer of three games for the 1980s text-adventure giant Infocom and of LucasArts’s own lovely, lyrical Loom. Of late, he’d been drafting a plan for a game based on The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, the franchise’s slightly disappointing foray into television, but a lack of personal enthusiasm for the project had led to a frustrating lack of progress. Moriarty was known as one of the most “literary” of game designers by temperament; his old colleagues at Infocom had called him “Professor Moriarty,” more as a nod to his general disposition than to the milieu of Sherlock Holmes. And indeed, his Trinity is as close as Infocom ever got to publishing a work of high literature, while his Loom possesses almost an equally haunting beauty. Seeing himself with some justification as a genuine interactive auteur, he demanded total control of every aspect of The Dig as a condition of taking it on. Bowing to his stellar reputation, LucasArts’s management agreed.

Much of what went on during the eighteen months that Moriarty spent working on The Dig remains obscure, but it plainly turned into a very troubled, acrimonious project. He got off on the wrong foot with many on his team by summarily binning Falstein’s vision — a vision which they had liked or even in some cases actively contributed to. Instead he devised an entirely new framing plot.

Rather than the far future, The Dig would now take place in 1998; in fact, its beginning would prominently feature the Atlantis, a Space Shuttle that was currently being flown by NASA. A massive asteroid is on a collision course with Earth. Humanity’s only hope is to meet it in space and plant a set of nuclear bombs on its surface. Once exploded, they will hopefully deflect the asteroid just enough to avoid the Earth. (The similarity with not one but two terrible 1998 movies is presumably coincidental.) You play Boston Low, the commander of the mission.

But carrying the mission out successfully and saving the Earth is only a prelude to the real plot. Once you have the leisure to explore the asteroid, you and your crew begin to discover a number of oddities about it, evidence that another form of intelligent being has been here before you. In the midst of your investigations, you set off a booby trap which whisks you and three other crew members light years away to a mysterious world littered with remnants of alien technology but bereft of any living specimens. Yet it’s certainly not bereft of danger: one crew member gets killed in gruesome fashion almost immediately when he bumbles into a rain of acid. Having thus established its bona fides as a serious story, a million light years away from the typical LucasArts cartoon comedy, the game now begins to show a closer resemblance to Falstein’s concept. You must explore this alien world, solve its puzzles, and ferret out the secrets of the civilization that once existed here if you ever hope to see Earth again. In doing so, you’re challenged not only by the environment itself but by bickering dissension in your own ranks.

This last element of the plot corresponded uncomfortably with the mood inside the project. LucasArts had now moved out of the idyllic environs of Skywalker Ranch and into a sprawling, anonymous office complex, where the designers and programmers working on The Dig found themselves in a completely separate building from the artists and administrators. Reading just slightly between the lines here, the root of the project’s troubles seems to have been a marked disconnect between the two buildings. Moriarty, who felt compelled to create meaningful, thematically ambitious games, became every accountant and project planner’s nightmare, piling on element after element, flying without a net (or a definitive design document). He imagined an interface where you would be able to carry ideas around with you like physical inventory items, a maze that would reconfigure itself every time you entered it, a Klein bottle your characters would pass through with strange metaphysical and audiovisual effects. To make all this happen, his programmers would need to create a whole new game engine of their own rather than relying on SCUMM. They named it StoryDroid.

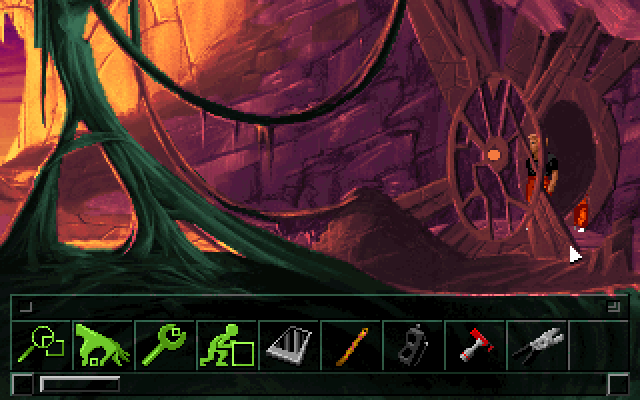

A screenshot from Moriarty’s version of The Dig. Note the menu of verb icons at the bottom of the screen. These would disappear from later versions in favor of the more streamlined style of interface which LucasArts had begun to employ with Sam and Max Hit the Road.

There were some good days on Moriarty’s Dig, especially early on. Bill Tiller, an artist on the project, recalls their one in-person meeting with Steven Spielberg, in his office just behind the Universal Studios Theme Park. Moriarty brought a demo of the work-in-progress, along with a “portable” computer the size of a suitcase to run it. And he also brought a special treat for Spielberg, who continued to genuinely enjoy games in all the ways George Lucas didn’t. Tiller:

Brian brought an expansion disk for one of the aerial battle games Larry Holland was making. Spielberg was a big computer-game geek! He was waiting for this upgrade/mission expansion thing. He called his assistant in and just mentioned what it was. She immediately knew what he meant and said she’d send it home and tell someone to have it installed and running for him when he arrived. I decided at that moment I would have an assistant like that someday.

Anyway, when we were through we told him we had a few hours to kill and wondered what rides we should get on back at the theme park. He said the E.T. ride, since he helped design it. It was brand new at the time. His people said that he was really crazy about it and wanted to show it off to everyone. One of his assistants took us there on a back-lot golf cart. We didn’t have to get another taxi. We didn’t even have to stand in line! They took us straight to the ride and cut us in the line in front of everyone, like real V.I.P.s. Everyone had to stand back and watch, probably trying to figure out who we were. All I remember is Brian with the stupid giant suitcase going through the ride.

But the best part of the whole thing for me was [Spielberg’s] enthusiasm. He really likes games. This wasn’t work to him to have to hear us go on about The Dig.

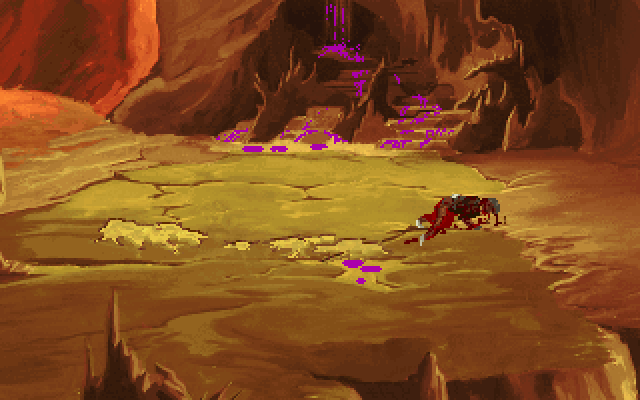

Brian Moriarty’s version of The Dig was more violent than later versions, a quality which Steven Spielberg reportedly encouraged. Here an astronaut meets a gruesome end after being exposed to an alien acid rain.

But the bonhomie of the Universal Studios visit faded as the months wore on. Moriarty’s highfalutin aspirations began to strike others on the team — especially the artists who were trying to realize his ever-expanding vision — as prima-donna-ish; at the end of the day, after all, it was just a computer game they were making. “I used to tell Brian, when he got all excited about what people would think of our creation, that in ten years no one will even remember The Dig,” recalls Bill Eaken, the first head artist to work under him. He believes that Moriarty may even have imagined Spielberg giving him a screenwriting or directing job if The Dig sufficiently impressed him. Eaken:

I liked Brian. Brian is a smart and creative guy. I still have good memories of sitting in his office and just brainstorming. The sky was the limit. That’s how it should be. Those were good times. But I think as time went on he had stars in his eyes. I think he wanted to show Spielberg what he could do and it became too much pressure on him. After a while he just seemed to bog down under the pressure. When all the politics and Hollywood drama started to impede us, when it wasn’t even a Hollywood gig, I [got] temperamental.

The programming was a complete disaster. I had been working for several years at LucasArts at that time and had a very good feel for the programming. I taught programming in college, and though I wasn’t a programmer on any games, I understood programming enough to know something was amiss on The Dig. I went to one of my friends at the company who was a great programmer and told him my concerns. He went and tried to chat with the programmers about this or that to get a look at their code, but whenever he walked into the room they would shut off their monitors, things like that. What he could see confirmed my worries: the code was way too long, and mostly not working.

The project was “completely out of control and management wouldn’t listen to me about it,” Eaken claims today. So, he quit LucasArts, whereupon his role fell to his erstwhile second-in-command, the aforementioned Bill Tiller. The latter says that he “liked and disliked” Moriarty.

Brian was fun to talk with and was very energetic and was full of good ideas, but he and I started to rub each other the wrong way due to our disagreement over how the art should be done. I wanted the art organized in a tight budget and have it all planned out, just like in a typical animation production, and so did my boss, who mandated I push for an organized art schedule. Brian bristled at being restricted with his creativity. He felt that the creative process was hindered by art schedules and strict budgets. And he was right. But the days of just two or three people making a game were over, and the days of large productions and big budgets were dawning, and I feel Brian had a hard time adjusting to this new age.

Games were going through a transition at that time, from games done by a few programmers with little art, to becoming full-blown animated productions where the artists outnumber the programmers four to one. Add to the mix the enormous pressure of what a Spielberg/Lucas project should be like [and] internal jealousy about the hype, and you have a recipe for disaster.

He wanted to do as much of the game by himself as possible so that it was truly his vision, but I think he felt overwhelmed by the vastness of the game, which required so much graphics programming and asset creation. He was used to low-res graphics and a small intimate team of maybe four people or less. Then there is the pressure of doing the first Spielberg/Lucas game. I mean, come on! That is a tough, tough position for one guy to be in.

One of LucasArt’s longstanding traditions was the “pizza orgy,” in which everyone was invited to drop whatever they were doing, come to the main conference room, eat some pizza, and play a game that had reached a significant milestone in its development. The first Dig pizza orgy, which took place in the fall of 1993, was accompanied by an unusual amount of drama. As folks shuffled in to play the game for the very first time, they were told that Moriarty had quit that very morning.

We’re unlikely ever to know exactly what was going through Moriarty’s head at this juncture; he’s an intensely private individual, as it is of course his right to be, and is not at all given to baring his soul in public. What does seem clear, however, is that The Dig drained from him some fragile reservoir of heedless self-belief which every creative person needs in order to keep creating. Although he’s remained active in the games industry in various roles, those have tended to be managerial rather than creative; Brian Moriarty, one of the best pure writers ever to explore the potential of interactive narratives, never seriously attempted to write another one of them after The Dig. In an interview he did in 2006 for Jason Scott’s film Get Lamp, he mused vaguely during a pensive interlude that “I’m always looking for another Infocom. But sometimes I think we won’t give ourselves permission.” (Who precisely is the “we” here?) This statement may, I would suggest, reveal more than Moriarty intended, about more of his career than just his time at Infocom.

At any rate, Moriarty left LucasArts with one very unwieldy, confused, overambitious project to try to sort out. It struck someone there as wise to give The Dig to Hal Barwood, a former filmmaker himself who had been friends with Steven Spielberg for two decades. But Barwood proved less than enthusiastic about it — which was not terribly surprising in light of how badly The Dig had already derailed the careers of two of LucasArts’s other designers. Following one fluffy interview where he dutifully played up the involvement of Spielberg for all it was worth — “We’re doing our best to capture the essence of the experience he wants to create” — he finagled a way off the project.

At this point, the hot potato was passed to Dave Grossman, who had, as noted above, worked for a time with Noah Falstein on its first incarnation. “I was basically a hedge trimmer,” he says. “There was a general feeling, which I shared, that the design needed more work, and I was asked to fix it up while retaining as much as possible of what had been been done so far — starting over yet again would have been prohibitively expensive. So I went in with my editing scissors, snip snip snip, and held a lot of brainstorming meetings with the team to try to iron out the kinks.” But Grossman too found something better to do as quickly as possible, whereupon the game lay neglected for the better part of a year while much of Moriarty’s old team went to work on Tim Schafer’s Full Throttle: “a project that the company loved,” says Bill Tiller, drawing an implicit comparison with this other, unloved one.

In late 1994, The Dig was resurrected for the last time, being passed to Sean Clark, a long-serving LucasArts programmer who had moved up to become the producer and co-designer of Sam and Max Hit the Road, and who now saw becoming the man who finally shepherded this infamously vexed project to completion as a good way to continue his ascent. “My plan when I came in on the final incarnation was to take a game that was in production and finish it,” he says. “I didn’t get a lot of pressure or specific objectives from management. I think they were mainly interested in getting the project done so they could have a product plan that didn’t have The Dig listed on it.” Clark has admitted that, when he realized what a sorry state the game was actually in, he went to his bosses and recommended that they simply cancel it once and for all. “I got a lot of resistance, which surprised me,” he says. “It was hard to resist the potential [of having] a game out there with a name like Spielberg’s on it.” In a way, George Lucas was a bigger problem than Spielberg in this context: no one wanted to go to the boss of bosses at LucasArts and tell him they had just cancelled his close friend’s game.

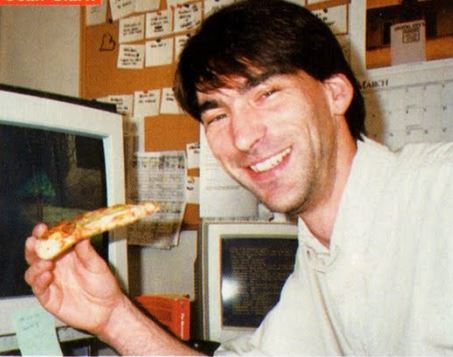

Sean Clark with a hot slice. Pizza was a way of life at LucasArts, as at most games studios. Asked about the negative aspects of his job, one poor tester said that he was “getting really, really tired of pizza. I just can’t look at pizza anymore.”

So, Clark rolled up his sleeves and got to work instead. His first major decision was to ditch the half-finished StoryDroid engine and move the project back to SCUMM. He stuck to Brian Moriarty’s basic plot and characters, but excised without a trace of hesitation or regret anything that was too difficult to implement in SCUMM or too philosophically esoteric. His goal was not to create Art, not to stretch the boundaries of what adventure games could be, but just to get ‘er done. Bill Tiller and many others from the old team returned to the project with the same frame of reference. By now, LucasArts had moved offices yet again, to a chic new space where the programmers and artists could mingle: “Feedback was quick and all-encompassing,” says Tiller. If there still wasn’t a lot of love for the game in the air, there was at least a measure of esprit de corps. LucasArts even sprang for a couple more (reasonably) big names to add to The Dig‘s star-studded marque, hiring the science-fiction author Orson Scott Card, author of the much-admired Ender’s Game among other novels, to write the dialogue, and Robert Patrick, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s principal antagonist from Terminator 2, to head up the cast of voice actors. Remarkably in light of how long the project had gone on and how far it had strayed from his original vision, Steven Spielberg took several more meetings with the team. “He actually called me at home one evening as he was playing through a release candidate,” says Sean Clark. “He was all excited and having fun, but was frustrated because he had gotten stuck on a puzzle and needed a hint.”

Clark’s practicality and pragmatism won the day where the more rarefied visions of Falstein and Moriarty had failed: The Dig finally shipped just in time for the Christmas of 1995. LucasArts gave it the full-court press in terms of promotion, going so far as to call it their “highest-profile product yet.” They arranged for a licensed strategy guide, a novelization by the king of tie-in novelists Alan Dean Foster, an “audio drama” of his book, and even a CD version of Michael Land’s haunting soundtrack to be available within weeks of the game itself. And of course they hyped the Spielberg connection for all it was worth, despite the fact that the finished game betrayed only the slightest similarity to the proposal he had pitched six years before.

Composer Michael Land plays timpani for The Dig soundtrack. One can make a strong argument that his intensely atmospheric, almost avant-garde score is the best thing about the finished game. Much of it is built from heavily processed, sometimes even backwards-playing samples of Beethoven and Wagner. Sean Clark has described, accurately, how it sounds “strange and yet slightly familiar.”

But the reaction on the street proved somewhat less effusive than LucasArts might have wished. Reviews were surprisingly lukewarm, and gamers were less excited by the involvement of Steven Spielberg than the marketers had so confidently predicted. Bill Tiller feels that the Spielberg connection may have been more of a hindrance than a help in the end: “Spielberg’s name was a tough thing to have attached to this project because people have expectations associated with him. The general public thought this was going to be a live-action [and/or] 3D interactive movie, not an adventure game.” The game wasn’t a commercial disaster, but sold at less than a third the pace of Full Throttle, its immediate predecessor among LucasArts adventures. Within a few months, the marketers had moved on from their “highest-profile product yet” to redouble their focus on the Star Wars games that were accounting for more and more of LucasArts’s profits.

One can certainly chalk up some of the nonplussed reaction to The Dig to its rather comprehensive failure to match the public’s expectations of a LucasArts adventure game. In a catalog that consisted almost exclusively of cartoon comedies, it was a serious, even gloomy game. In a catalog of anarchically social, dialog-driven adventures that were seen by many gamers as the necessary antithesis to the sterile, solitary Myst-style adventure games that were now coming out by the handful, it forced you to spend most of its length all alone, solving mechanical puzzles that struck many as painfully reminiscent of Myst. Additionally, The Dig‘s graphics, although well-composed and well-drawn, reflected the extended saga of its creation; they ran in low-resolution VGA at a time when virtually the whole industry had moved to higher-resolution Super VGA, and they reflected as well the limitations of the paint programs and 3D-rendering software that had been used to create them, in many cases literally years before the game shipped. In the technology-obsessed gaming milieu of the mid-1990s, when flash meant a heck of a lot, such things could be ruinous to a new release’s prospects.

But today, we can presumably look past such concerns to the fundamentals of the game that lives underneath its surface technology. Unfortunately, The Dig proves far from a satisfying experience even on these terms.

An adventure game needs to be, if nothing else, reasonably good company, but The Dig fails this test. In an effort to create “dramatic” characters, it falls into the trap of merely making its leads unlikable. All of them are walking, talking clichés: the unflappable Chuck Yeager-type who’s in charge, the female overachiever with a chip on her shoulder who bickers with his every order, the arrogant German scientist who transforms into the villain of the piece. Orson Scott Card’s dialog is shockingly clunky, full of tired retreads of action-movie one-liners; one would never imagine that it comes from the pen of an award-winning novelist if it didn’t say so in the credits. And, even more unusually for LucasArts, the voice acting is little more inspired. All of which is to say that it comes as something of a relief when everyone else just goes away and leaves Boston Low alone to solve puzzles, although even then you still have to tolerate Robert Patrick’s portrayal of the stoic mission commander; he approaches an unknown alien civilization on the other side of the galaxy with all the enthusiasm of a gourmand with a full belly reading aloud from a McDonald’s menu.

Alas, one soon discovers that the puzzle design isn’t any better than the writing or acting. While the puzzles may have some of the flavor of Myst, they evince none of that game’s rigorous commitment to internal logic and environmental coherence. In contrast to the free exploration offered by Myst, The Dig turns out to be a quite rigidly linear game, with only a single path through its puzzles. Most of these require you just to poke at things rather than to truly enter into the logic of the world, meaning you frequently find yourself “solving” them without knowing how or why.

But this will definitely not happen in at least two grievous cases. At one point, you’re expected to piece together an alien skeleton from stray bones when you have no idea what said alien is even supposed to look like. And another puzzle, involving a cryptic alien control panel, is even more impossible to figure out absent hours of mind-numbing trial and error. “I had no clue that was such a hard puzzle,” says Bill Tiller. “We all thought it was simple. Boy, were we wrong.” And so we learn the ugly truth: despite the six years it spent in development, nobody ever tried to play The Dig cold before it was sent out the door. It was the second LucasArts game in a row of which this was true, indicative of a worrisome decline in quality control from a studio that had made a name for themselves by emphasizing good design.

At the end of The Dig, the resolution of the alien mystery is as banal as it is nonsensical, a 2001: A Space Odyssey with a lobotomy. It most definitely isn’t “an in-depth story in which the exploration of human emotion plays as important a role as the exploration of a game world,” as LucasArts breathlessly promised.

So, The Dig still manages to come across today as simultaneously overstuffed and threadbare. It broaches a lot of Big Ideas (a legacy of Falstein and Moriarty’s expansive visions), but few of them really go anywhere (a legacy of Grossman and Clark’s pragmatic trimming). It winds up just another extended exercise in object manipulation, but it doesn’t do even this particularly well. Although its audiovisuals can create an evocative atmosphere at times, even they come across too often as disjointed, being a hodgepodge of too many different technologies and aesthetics. Long experience has taught many of us to beware of creative expressions of any stripe that take too long to make and pass through too many hands in the process. The Dig only proves this rule: it’s no better than its tortured creation story makes you think it will be. Its neutered final version is put together competently, but not always well, and never with inspiration. And so it winds up being the one thing a game should never be: it’s just kind of… well, boring.

As regular readers of this site are doubtless well aware, I’m a big fan of LucasArts’s earlier adventures of the 1990s. The one complaint I’ve tended to ding them with is a certain failure of ambition — specifically, a failure to leave their designers’ wheelhouse of cartoon comedy. And yet The Dig, LucasArts’s one concerted attempt to break that mold, ironically winds up conveying the opposite message: that sometimes it’s best just to continue to do what you do best. The last of their charmingly pixelated “classic-look” adventure games, The Dig is sadly among the least satisfying of the lot, with a development history far more interesting than either its gameplay or its fiction. A number of people looked at it with stars in their eyes over the six years it remained on LucasArts’s list of ongoing projects, but it proved a stubbornly ill-starred proposition for all of them in the end.

(Sources: the book The Dig: Official Player’s Guide by Jo Ashburn; Computer Gaming World of March 1994, September 1994, September 1995, October 1995, December 1995, and February 1996; Starlog of October 1985; LucasArts’s customer newsletter The Adventurer of Spring 1993, Winter 1994, Summer 1994, Summer 1995, and Winter 1995. Online sources include Noah Falstein’s 2017 interview on Celebrity Interview, Falstein’s presentation on his history with Lucasfilm Games for Øredev 2017, the “secret history” of The Dig at International House of Mojo, the same site’s now-defunct “Dig Museum,” ATMachine’s now-defunct pages on the game, Brian Moriarty’s 2006 interview for Adventure Classic Gaming, and Moriarty’s Loom postmortem at the 2015 Game Developers Conference. Finally, thank you to Jason Scott for sharing his full Get Lamp interview archives with me years ago.

The Dig is available for digital purchase on GOG.com.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | LucasArts was known as Lucasfilm Games until the summer of 1992. To avoid confusion, I use the name “LucasArts” throughout this article. |

|---|

Benjamin M Vigeant

July 23, 2021 at 4:50 pm

Typo: Ender’s Game (not Endor’s Game)

Great piece.

I will say though, as a person that read a lot of Orson Scott Card’s novels as a teen, I wouldn’t consider him someone that was particularly gifted with natural dialogue. I’d want him more as a Big Ideas guy, and it seems like this already had enough of them.

Jimmy Maher

July 23, 2021 at 4:52 pm

Thanks!

Lt. Nitpicker

July 23, 2021 at 4:51 pm

> Endor’s Game

This typo is kinda funny since you were talking about LucasArts,but the correct spelling is Ender’s Game.

Lt. Nitpicker

July 23, 2021 at 4:59 pm

And another one:

> but wisely abandoned the clichéd reveal of Micky Mouse.

(You correctly spelled Mickey Mouse a couple sentences back from this quote, incidentally)

Jimmy Maher

July 23, 2021 at 5:04 pm

Thanks!

Nate

July 23, 2021 at 4:58 pm

I’m not sure the photo of the design session was from 1989. It appears that some people have silver laptops and another has a flip phone? Maybe this was early 2000’s?

Jimmy Maher

July 23, 2021 at 5:04 pm

Ouch. Thanks!

Jason Dyer

July 23, 2021 at 5:24 pm

Agreed the soundtrack is the best thing on the game.

I didn’t find the two puzzles you cite overly distressing (I heard the bones puzzles was infamous after I had solved it, but surely it doesn’t sink to the demolition derby puzzle level) although the control panel was probably too early and could have used an extra clue or two.

I wasn’t necessarily disappointed by the initial clichés, but figured the characters would develop as time went on. They did not. All the character interaction was awkward and tentative, like the developers really just wanted object-fiddling but had to deal with these pesky people.

CdrJameson

July 24, 2021 at 9:09 pm

I played it recently with no idea of the game’s history or development woes and I really quite liked it. It had a refreshingly serious and intriguing setup, the puzzles were diverse and largely fitted in with the world and exploring a mysterious alien planet was always going to be fun.

The disappointments for me were the rather unsympathetic and wooden lead character (although from other accounts this might be an accurate portrayal of a senior astronaut), one confusing not-even-puzzle where a button has to be held, not just pressed, and inevitably the ending which by resolving things obviously destroys a lot of the mystery.

The bones puzzle is pretty straightforward if you spot the MASSIVE CLUE nearby.

The alien control panel is just a fun little challenge if you happen to be a computer programmer, but I accept it might take a while if you aren’t.

All in all I found it one of the more enjoyable Lucasarts adventures because it was so different. I mean, not a patch on Day of The Tentacle, but still excellent in its own way.

Infocom had of course tackled similar ground with Rama-with-the-numbers-filed-off Starcross some time earlier.

Jake Wildstrom

July 23, 2021 at 5:46 pm

[Falstein] was pulled off the project very early in 1991, assigned instead to help Hal Barwood with Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. And when this, his second Indiana Jones game, was finished, he was laid off despite a long and largely exemplary track record.

Is there any good explanation for whythis happened? That seems to be a rather extraordinary turn of events to happen to the successful designer on a flagship product unless there was some sort of falling-out with management.

a Klein bottle your characters would pass through with strange metaphysical and audiovisual effects

Is it unfair to accuse Moriarty of recycling a (cleverly used) device from Trinity here?

Jimmy Maher

July 23, 2021 at 6:09 pm

Falstein himself has avoided directly explaining the circumstances of his departure, and I don’t feel it’s really my place to speculate any deeper. I generally hesitate to dig too hard after such things; getting demoted or fired is unpleasant enough without the details being published on the Internet.

And yeah, Moriarty obviously did have a fascination with Klein bottles. ;)

Arthur

July 23, 2021 at 6:45 pm

I’ve written about my thoughts on the Dig elsewhere (https://fakegeekboy.wordpress.com/2020/09/08/gogathon-curses-grimly-market-forces-throttled-a-genre-but-it-escaped-dig-it/) but they’re largely in line with yours.

It feels like the story suffers from a bunch of elements which no longer quite make sense in the version we eventually got to play, because they’re holdovers from old versions. Ones I remember vividly are as follows:

– Boston jumps to the conclusion of using some of the McGuffin crystals to revive one of the crew members. When I played the game this felt like a bit of a wild leap in the dark, and didn’t see why Boston would have any reason to expect this would work; he’s working off images shown in a particular museum, but these are monochromatic, unclear images, in which it is far from self-evident that the material used for revival is the same as that Boston uses to save his crewmate. Apparently in an earlier iteration these images were meant to be realistic full-colour holograms – so it’d be much more unambiguous what substance was being used.

– More fundamentally, why are half the crew even here? Earth is in mortal peril, the collapse of civilisation is imminent, this is NASA’s one and only chance to steer the asteroid off-course. Why send up an archaeologist and a linguist when they could send up people with more directly relevant expertise, so as to provide redundancy of skillset just in case? It’s absurd. Even though there’s some throwaway lines about NASA suspecting something might be up with the asteroid to semi-justify it, it still feels like an utterly pointless gamble with the lives of everyone on the planet, including those responsible for signing off on the plan. Just send the demolition specialists up to do the job, then send the scientific party along as a follow-up mission.

– Why does the cranky German keep insisting that he should be in charge as an archaeologist? This is not and has never been a specifically archaeological mission. This would make way more sense if the expedition was an archaeological trip from the start and was briefed as such. Sure, sure, he’s meant to be the unreasonable one who goes off the rails, but this doesn’t make him look like a villain or a troubled genius, it makes him seem like a whiny goof.

– Why do so many puzzles involve the shovel? Well, if they didn’t the name would make absolutely no sense, because this mission isn’t an archaeological dig!

Fuck David Cage

July 23, 2021 at 9:02 pm

My guess is that Lucasarts was inspired by the Rama series, which was made into an excellent adventure game by Sierra. Rama involved Earth being threatened by a large object which appeared to be an asteroid, but when it came closer turned out to be a spaceship. Sending archaeologists and linguists was a logical move in that series since the planners knew they were dealing with the first signs of aliens.

Arthur

July 23, 2021 at 11:28 pm

See, that makes sense! But in The Dig it literally comes across like they just thought it might be an alien ship as a remote possibility, and tossed in those personnel on a just-in-case basis.

It’d be much better to just drop the “Earth in danger” angle – something which is never actually all that important to the game, because you resolve it with the first puzzle – and say “hey, it’s an anomalous asteroid, NASA are sending an expedition to check it out, the archaeologist and linguist are there just in case”. It would better support the rest of the plot and avoid the need for complications about secret NASA in-case-of-aliens-follow-instructions protocols.

Then again, it might be even more Rama-ish – in the original novel as I recall NASA knows it’s an anomalous object from the start – and they might have been hesitant about potentially treading on toes, especially since Sierra probably had the licence by this point (the game developed by Dynamix came out in 1996 after all). On the other hand, the actual concept we get is still a hell of a lot like Rama – it just makes less sense. Boggles the mind.

Richard

July 24, 2021 at 7:08 am

The “meteor about to hit earth” thing never made any sense to me – the press conference shown in the intro cutscene is very relaxed and laid back, as if it’s just going to be a routine shuttle mission. And when they get to the meteor it’s *really* close to Earth but seems to be just gently orbiting it? At that distance it would have been just seconds from impact if it really were on a collision course.

A very simple fix would have been to just say that there’s a strange meteor that has entered the Earth’s orbit and a team is going to investigate. That would cleanly justify sending a reporter and an archeologist, and would fix all the illogicalities in the premise.

Arthur

July 23, 2021 at 7:05 pm

Oh, one more thought. It’s interesting that this story involves LucasArts management refusing to cancel a point-and-click adventure project which they perhaps should have, rather than cancelling a project where the developers felt that it was in good shape and was close to completion (as happened with Sam and Max: Freelance Police).

Could the commercial flop of The Dig have inadvertently led to LucasArts management being more trigger-happy about cancelling adventure games, because they had the chance to walk away from The Dig and didn’t take it and ended up regretting it?

Andrew Plotkin

July 23, 2021 at 7:07 pm

> nearly 80 years since the McKillip Drive made faster-than-light travel a possibility…

Has anyone ever dug into this? Patricia McKillip isn’t as well-known a writer as Orson Scott Card, but any SF/F fan reading an intro in 1991 would recognize her name. (Her one pure-SF novel, _Fool’s Run_, was published in 1987.) Was this a deliberate homage?

Jimmy Maher

July 23, 2021 at 10:02 pm

I’m not familiar with her at all, but I would certainly guess it to be a deliberate homage given your description. It seems an odd name to make up out of the blue.

Fuck

July 23, 2021 at 8:45 pm

This game was disappointing and mediocre, but an ideal, near perfect sci fi game came out in 1995: Chrono Trigger. Chrono Trigger is my favorite R.P.G. and it has a great story, great characters, a great sense of mystery and adventure as you explore a variety of settings in different time periods. Time travel is used perfectly: It really makes you feel accomplished as you watch time change based on your actions, the effects on both story and gameplay are quite significant and comparing the different time periods gives you great insights into the world and the characters.

Chrono Trigger looks cartoonish, but it actually explores darker themes like the cruelty of evolution and the endless finality of death. Enemies seem like monsters at first, but as you explore their history you realize that they are the victims of the capricious hand of evolution. You explore cities made by the enemies, can forgive a villain and add him to your party, and even make them the dominant species in an alternate ending.

Chrono Trigger had about 13 endings, all based on the time period in which you kill the final boss; and these endings are quite satisfying. They range from serious to satisfying to surreal and they give the game endless replay value. They also encourage carefully leveling the party, as some of the endings require beating the game early, with poor characters.

Owen C.

July 24, 2021 at 5:33 am

Chrono Trigger is a great and well known game (they even played its music on the Olympics opening ceremony yesterday after all) but this site normally limits its scope to only writing about PC games. There is plenty of stuff written about it elsewhere on the Internet already.

On another note, I can confirm that The Dig was also pretty boring and disappointing for someone like me who came into it who liked Myst style adventure games, never really got into LucasArts or Sierra but bought into the marketing glitz and Spielberg hype surrounding the game. Mostly, like was said in the article it felt dated and the puzzles didn’t seem to have much obvious logic behind them.

No

July 23, 2021 at 8:57 pm

> the earthquake collapsed San Francisco’s Nimitz Freeway

*Oakland’s

Wrong side of the bay :)

Jimmy Maher

July 23, 2021 at 9:59 pm

:) Thanks!

Eric Nyman

July 23, 2021 at 8:58 pm

I think the lack of graphics fidelity hurt their attempt to have Myst-style puzzles. You really need to be able to show the machines and devices in detail to pull off that type of a game (Zork III tried one such puzzle in text form, and while they did their best, it’s unwieldy).

It’s a shame that Moriarty never got to finish this game. I think his version would have been much better than the ultimate end product. There were a lot of good ideas here, but as others said, it just feels frustratingly unfinished and rushed.

It’s also too bad he hasn’t gotten back into producing or writing games. Nowadays he would find it much easier to independently produce games without having to be restricted by budgets and other constraints imposed by a major studio, and he’d also be freed of many of the technical and file size constraints that Infocom faced as well (imagine a version of A Mind Forever Voyaging or Trinity without such impositions with more room to really flesh things out).

Instead of space tourism or whatnot, I wish a few rich people would invest seed money for an interactive fiction/adventure game company (or at least donate to existing projects). There’s a lot of talented, hard working people in the field who deserve to be able to “given permission” as Moriarty put it to be able to show what they could really do if they could throw themselves into the work full time.

fform

July 25, 2021 at 2:58 am

On the one hand, I agree that it’s a shame that Moriarty hasn’t gotten back into making games in the present environment given the new tools for creation and distribution we have available, and the massive popularity of independent gaming at present.

On the other hand, given the description of his work and creative style on this particular project, perhaps the file size limitations were a blessing in disguise. So many artists, when given an infinite canvas, show that they need restrictions in order to pare down their vision to the core elements. Sometimes the infinite canvas works, for example with the mind-boggling complexity of Dwarf Fortress (arguably works, I guess), but most artists need editing and in most cases the artist feels that they’re the only ones capable of doing the editing. They often don’t bother, and their work suffers badly for it.

LasseS

July 25, 2021 at 6:22 am

Agreed, the Dig feels like a neutered game that’s been rushed out. It is a bland and even dull experience and I think this is largely due to so much of it being cut and changed just to get it out of the door ASAP.

Would love to see what Brian Moriarty’s version would have been had it been finished, he did seem to have some vision and passion for the game which the final game sadly seems to lack.

I wish Brian Moriarty would do what Bob Bates did with Thaumistry and just do another fully text based game solo…

That game clearly wasn’t some big money maker though, but personally I really enjoyed it.

Michael

July 23, 2021 at 9:32 pm

“after many torturous twists and turns”

=tortuous

Jimmy Maher

July 23, 2021 at 10:00 pm

I’m slightly embarrassed to admit that I never knew that “torturous” and “tortuous” are separate words. Thanks!

Arthur

July 26, 2021 at 5:06 pm

To be fair I think “torturous turns” actually makes more sense than “tortuous turns”. The former implies that these turns are painful and traumatic, which is apt for this story and the growing pains the project went through. The latter just means “turny turns”; it’s a redundancy.

Arthur

July 26, 2021 at 5:06 pm

(I mean, I know “tortuous turns” is the more usual turn of phrase… I just don’t think it’s a very good phrase! “Torturous turns” is a) a legitimate phrasing and b) better.)

Jimmy Maher

July 27, 2021 at 5:10 am

I like it better too, and I’m going to take this as a form of validation. ;) Thanks!

Jeff C.

July 23, 2021 at 10:46 pm

“…all the enthusiasm of a gourmand with a full belly reading aloud from a McDonald’s menu.”

That’s hilarious…I’m not sure how I’ll do it, but I somehow HAVE to work that phrase into a conversation.

DZ-Jay

May 2, 2023 at 6:13 pm

Personally, I love the colorful account of meeting Spielberg, describing him as a regular guy, someone who “sneezes and drops forks,” like the rest of us.

That’s hilarious!!!

dZ.

Diego

July 24, 2021 at 1:25 am

Thanks for this insightful article. I, for one, really enjoyed playing The Dig and most of the criticism about the final game makes little sense to me.

The graphics are so beautifully done in all its pixelated glory, suggestive and mysterious, the animations are great and the use of colours is truly excellent (all those warm orange shades with the cold blues for contrast!).

The story doesn’t go deep trying to explain everything carefully and I don’t think it needs to. Feels more mature than other Lucas games (which of course I also enjoyed immensely) and have a serious dramatic atmosphere. I think the story and the characters do evolve in fascinating ways for a video game of its time.

The only criticism I can agree on is in the difficulty of some of its puzzles, which are a bit cryptic.

Just adding my two cents and standing up for it, as for me it will always be the last great point and click adventure game of a fading era.

It was a pleasure reading about its convoluted creation process. Thanks again!

dusoft

July 24, 2021 at 7:20 pm

Indeed, I played it as a teenager and was just fascinated both by graphics, the life crystals idea and the gloomy atmosphere. I loved the cut scenes where you traveled in globes etc.

I don’t remember if the puzzles were really such pain in the ass.

Ninja DOdo

August 21, 2021 at 11:57 am

Some of the criticisms in this article really aren’t fair to the puzzles. The alien control panel wasn’t actually that hard to figure out with a little experimentation and saying the skeleton reconstruction has no hints is completely untrue as there is a very obvious hint in the form of the living alien turtle creature right next to it at the water edge, which shows up repeatedly, so you really can’t miss it.

An otherwise interesting retrospective somewhat marred by the highly subjective (and unwarranted) negative tone of the conclusion.

Ninja Dodo

August 21, 2021 at 9:16 pm

I will say there are some puzzles that are genuinely unfair or lacking in hints, like the one where you have to press and HOLD a button instead of simply pressing it (which you’re never taught to do and this input is used nowhere else in the game), and there are moments where there is a lack of direction and few hints on what you should even be focusing on, which can lead to aimless wandering and trying random things. Overall, while I did consult hints once or twice, it’s quite approachable as point & click adventures go.

There are occasional weird leaps of logic in the writing where the characters seem to understand things before the player does for no apparent reason, or make some pretty wild assumptions. Nevertheless, it is an intriguing and highly atmospheric game… and I say this having just recently played it for the first time, so that’s not nostalgia talking.

Adam M

July 31, 2021 at 2:11 am

I for one entirely agree with you. I posted my own comment further down. Often, the mood or style of a game is enough for me. I don’t need or expect technical or artistic perfection in a game, and I couldn’t care less whether a game had a tortured development path. I won’t wince at hard or obscure puzzles either, having been trained on Sierra games. Incidentally, on the subject of the graphics, the 1993 artwork in a 1995 game is less important now, particularly given the new found popularity of pixel art adventure games with a retro feel. Anyway, like with movies, I don’t care what other people think. The bar I set is whether I enjoy something or not. I enjoyed playing The Dig, and I thank all those involved in making it.

Kai

July 31, 2021 at 9:33 am

Yep, I loved every bit of it when I played it back then. From the iridescent game box to the cinematic intro and cut-scenes, the background music, the Sci-Fi theme, the art style, the voice overs … and the list goes on.

I’m not sure whether I would regard it with the same favour if I played it for the first time today, but for 1995 I think it was as good as one could possibly hope for.

I’m not quite certain if I was entirely happy with the puzzles or the ending, but if I had any issues than those must have been that there weren’t enough puzzles and that the ending came too soon.

The Eidolon

July 24, 2021 at 3:11 am

Great timing on this article. Alan Dean Foster’s autobiography just came out this week, and chapter 19 is about–The Dig.

Aula

July 24, 2021 at 5:19 am

“a less enviable role than then he had envisioned”

I don’t know if there’s any situation where “than then” would be correct, but this isn’t one of them.

Jimmy Maher

July 24, 2021 at 7:33 am

Thanks!

njarboe

July 24, 2021 at 6:30 am

Just a small correction. The Nimitz freeway is in Oakland not San Francisco.

Kaj Sotala

July 24, 2021 at 8:35 am

Oh man, I really hoped that you’d have kinder words for what’s one of my all-time favorite adventure games. I do agree with most of your criticisms – the characters aren’t very deep, and there were indeed a couple of terrible puzzles… but to me, the main appeal of the game was always the delight of getting to explore a beautiful, haunting alien world.

I always felt that from the moment during the opening cutscene when Commander Low says “we have only one chance to get it right” to when the end credits start rolling, there’s a constant sense of majesty from the characters being somewhere that’s much vaster and older than they are. A sense that the game quite skillfully maintains, with e.g. all the seemingly “filler” screens that just involve the character walking from one end of it to the other, giving the player the opportunity to just pause for a moment as their eyes take in the sights and sounds. (And the music is indeed gorgeous.)

Kaj Sotala

July 24, 2021 at 8:37 am

(Er, as *they take in the sights and sounds. Their eyes probably don’t take in sounds, unless they have synesthesia.)

Jonathan Badger

July 24, 2021 at 10:58 am

“They were digging at Disneyland, right here on Planet Earth! The problem here was that we had seen all of this before, most notably at the end of Planet of the Apes”

I don’t think that’s the same trope at all, though. The shock at the end of the Planet of the Apes wasn’t that it was just Earth, it was the horror that the Earth the astronauts knew had been destroyed (“God damn it, you blew it to hell!”). The idea of future archeologists digging up ruins of our civilization (and often humorously misinterpreting things, like assuming Mickey Mouse was our god), is a different thing, although it has been also been done before (Macaulay’s “Motel of the Mysteries” and the Pepsi ad where the Pepsi-drinking future archeologist has no idea what Coca-Cola was, etc.)

Petter Sjölund

July 24, 2021 at 1:07 pm

While The Dig may not have lived up to its hype, it is still head and shoulders above pretty much all contemporary non-LucasArts adventure games. The most obvious comparison is Dynamix’ RAMA, which has all the higher-resolution graphics and full-motion video (lots of it!) that The Dig missed out on, but turned out super boring. Playing them today, The Dig is clearly the better game by every measure.

Playing the Dig in 1995, I loved the more serious tone and Myst-like puzzles, and had a great time until the happy ending, which completely ruined it for me.

Sebastian Gerstl

July 24, 2021 at 2:52 pm

In remember back in the day that German gaming magazines (traditionally very good of adventure games in general) were actually for the most part pretty smitten with the game when it came out; at least one of them felt its puzzles in particular were more of a “return to form” for Lucas Arts when compared to the”more lackluster and simplistic” Full Throttle (their words not mine).

But interestingly the shine went off pretty quickly… I remember reading about a comparison of adventure games some time in early 1996, were the editor complained about the lack of depth in more recent adventure games. As an example he pulled out a comparison of locations and inventories: where “Fate of Atlantis” could provide more than a dozen individual distinct locations, many with dozens of screens themselves, and about a hundred different inventory items (he actually provided a concise number, but unfortunate I can’t find the article in question or I would provide a link), the dig could only provide for a very limited amount of screens on two locations, many of which looking rather similar, and about 40 inventory items, 12 of which simply being various rods that serve as keys. That may be a bit nitpicky in comparison, but it kind of shows how drastically limited and reduced in scope “The Dig” felt like when compared to earlier LA games. (Though the location comparison isn’t really fair IMO – Day of the Tentacle has a very limited amount of screens, the same locations repeated over three time zones – but on the other hand, even in that limited space, there was just so much you could DO there. The Dig, on the other hand, feels empty and lifeless – which might provide a decent atmosphere, but didn’t really oder much in terms of fun or entertainment.

If you want I can try locating the article in question – I’m pretty sure a scan must exist online somewhere. It must’ve been either PC Player or Power Play Magazine I believe, because those were the ones I read regularly at the time…

Jimmy Maher

July 25, 2021 at 7:36 am

I appreciate the sentiment of the article you describe, but I’m not sure there’s much value to trying to quantify things in such a way. The Dig’s issues don’t involve complexity or a lack thereof, but a thoroughgoing incoherence in its writing, aesthetics, and, yes, puzzle structure, capped off by a presumption of profundity which it never earns. As you note, more rooms don’t automatically make a better game, nor even a bigger — i.e., more time-consuming — one. The absurd end point of this kind of argument is the advertisements that Level 9 published for their text adventure Snowball in 1983: “over 7000 locations!” What they neglected to mention was that 6900 of them were empty red herrings…

Actually, none of the classic LucasArts adventures strike me as all that *big*. And this is generally to their benefit rather than detriment. Less stuff means more opportunity to polish the stuff you do have.

Sebastian Gerstl

July 25, 2021 at 8:09 am

Yeah … I guess the trick is not how expansive your game is, but what you do with the resources available. I also get how a game centered around a crew flung deep into space, far from home, might benefit from a forlorn and more or less “lifeless” atmosphere. But the problem is that The Dig doesn’t give you all that much to do in the environs, not much to observe, so you walk through empty rooms, collect keys and solve puzzles to open new passageways. Which may also be down to the fact that the game was cut down immensely to finally get it done already, but it just seems so uninspired as a result… Not to mention a bit boring. It still has that spark of LucasArts adventure magic, but in the end I would agree that it’s over of their lesser offerings

Martin

July 24, 2021 at 7:08 pm

So a genetL question. Had there ever been a game that had this sort of birth that ended up being a “good” game? You can define “good” in any way you choose.

Martin

July 24, 2021 at 7:09 pm

The word in the first sentence was supposed to be “general”.

Sebastian Gerstl

July 24, 2021 at 9:09 pm

Resident Evil 4 had three or four incarnations that were discarded and started anew over a span of six years before eventually being released. And many consider that a classic, reinvigorating the Survival Horror and introducing many gameplay mechanics now considered standard into third-person perspective games. So Yeah… It may be rare, but it can be done.

DZ-Jay

May 2, 2023 at 6:25 pm

I did not know about Resident Evil 4’s tortuous genesis, but I personally found the game itself to be a masterpiece. Not only did it reinvigorated the Survival Horror genre, as you mentioned but, horror themes aside, it showed the world how such types of story-driven, third-person action games can be done right.

dZ.

Rowan Lipkovits

July 25, 2021 at 7:34 am

It certainly seemed to suffer a similar origin and fate to Infocom’s Bureaucracy!

Jimmy Maher

July 25, 2021 at 7:50 am

Infocom’s version of The Dig was Bureaucracy, right down to the detail of being almost impossible to cancel thanks to the involvement of a high-profile figure who provided the initial idea and then not much else that was all that useful — Douglas Adams in this case. I think it turned out pretty well, although that sentiment is by no means universal.

Starflight is another early example of development hell, a game that became a joke at Electronic Arts because of the way it kept turning up like a bad penny at every planning meeting for the first four years of the company’s existence. It’s now universally acknowledged as a classic.

So, yeah, there are exceptions. But the pattern of The Dig is more the norm.

CdrJameson

July 26, 2021 at 4:57 pm

Half-Life was largely scrapped and rewritten from scratch part way through development.

That is generally considered to have turned out OK.

Gnoman

July 26, 2021 at 9:42 pm

I think the big thing here is that most of the counter examples were ones where the company had the sense to just throw it all into the trash, maybe pulling a few bits out for another project or two.

Games like this one almost always get most of their problems by keeping stuff that no longer fits. The premier example from the article is The Dig’s severely dated graphics. Another well-known example is Duke Nukem Forever, which had core elements (particularly the heavy sexualization that was massively transgressive when the previous game was released in 96) that were nearly 20 years old at the time of release and were no longer culturally relevant.

Sometimes the solution to a failing project is to shoot the engineer. Sometimes, however, you just have to put the dog down.

Josh Martin

July 31, 2021 at 5:51 pm

The fourth Doom game started development at least as far back as 2008, was completely rebooted in 2011, survived the departure of much of the original staff in 2013, and came out in 2016 to broad acclaim despite the numerous red flags (including Bethesda’s refusal to send out review copies).

Lhexa

October 26, 2021 at 3:26 am

Demon’s Souls is a good example. Miyazaki is a vanishingly rare creator talented both as a designer and a manager. He helped turned a collection of disparate assets into the prototype of a new genre.

PRI

July 24, 2021 at 11:17 pm

You seem to enjoy humorous games a lot more than dramatic ones. I could’ve just forgotten, but I can’t recall an article where you speak highly of a serious, non-comedic adventure game.

Eriorg

July 25, 2021 at 12:52 pm

There was at least Trinity: https://www.filfre.net/2015/01/trinity/

Derek

July 26, 2021 at 5:15 am

I think Maher’s attitude — which he’s made clear enough times that I feel fairly safe in summarizing it for him — is more complex than that. His review of The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes (a largely serious game, by the sound of it, and one he regards highly), says “the classic approach to the adventure game, as a series of physical puzzles to solve, can be hugely entertaining, but it almost inevitably pushes a game toward comedy, often in spite of its designers’ best intentions.” Note also his reviews of Gabriel Knight and Police Quest: Open Season, which criticize those games’ designs while crediting Sierra for aspiring to move beyond comedy. The problem is that it’s harder to make an adventure game that is both serious and playable. But Maher has written several positive reviews of mostly serious games, ranging from Zork III to Myst, in addition to his obvious admiration for Trinity.

Michael Davis

July 26, 2021 at 8:09 pm

Plus, he *did* actually *make* one…

PRI

July 26, 2021 at 8:29 pm

He did? What’s it called?

Derek

July 27, 2021 at 12:34 am

The King of Shreds and Patches.

Lisa H.

July 27, 2021 at 12:57 am

There’s a link in the sidebar on the right – http://maher.filfre.net/King

Goatmeal

July 25, 2021 at 2:53 am

“Of late, he’d been drafting a plan for a game based on The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, Spielberg’s latest disappointing foray into television, but a lack of personal enthusiasm for the project had led to a frustrating lack of progress.”

I believe that The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles was solely George Lucas’s pet project (“created by,” “story”/”based on a story by,” and “executive producer”) and that Spielberg had very little — if anything — to do with it. If he did contribute something to the series, he’s not credited on IMDB…

Jimmy Maher

July 25, 2021 at 7:25 am

Fair enough. Thanks!

Adam M

July 31, 2021 at 1:38 am

I remember playing the game through twice, and while it suffered from some obscure puzzles, I appreciated the overall aesthetic and vision of the game, although imperfectly realized. It was thought provoking at many points, and the art is actually quite pretty in my opinion. However, Michael Land’s brilliant score is the enduring legacy of this game. I have the original score and also the “bonus” soundtrack. Some of the best ambient music I have heard and it has often got me through long bouts of report and essay writing. I’ll always have a soft spot for The Dig and I’m glad they managed to get it made.

Kai

July 31, 2021 at 5:08 pm

“his Trinity is a close as Infocom ever got to” – missing an ‘s’.

Jimmy Maher

August 1, 2021 at 10:52 am

Thanks!

Bernie Paul

August 6, 2021 at 4:19 pm

Well, this has been said many times here already, but I also liked the game. Still got my copy around, without the box but with the companion novel.

Speaking of the novel, the part of the package least discussed here, I read it before booting the game and found it quite enjoyable. It set up the scenario very well for me and I think Alan Dean Foster deserves credit for helping the game enormously.