Robyn Miller, one half of the pair of brothers who created the adventure game known as Myst with their small studio Cyan, tells a story about its development that’s irresistible to a writer like me. When the game was nearly finished, he says, its publisher Brøderbund insisted that it be put through “focus-group testing” at their offices. Robyn and his brother Rand reluctantly agreed, and soon the first group of guinea pigs shuffled into Brøderbund’s conference room. Much to its creators’ dismay, they hated the game. But then, just as the Miller brothers were wondering whether they had wasted the past two years of their lives making it, the second group came in. Their reaction was the exact opposite: they loved the game.

So would it be forevermore. Myst would prove to be one of the most polarizing games in history, loved and hated in equal measure. Even today, everyone seems to have a strong opinion about it, whether they’ve actually played it or not.

Myst‘s admirers are numerous enough to have made it the best-selling single adventure game in history, as well as the best-selling 1990s computer game of any type in terms of physical units shifted at retail: over 6 million boxed copies sold between its release in 1993 and the dawn of the new millennium. In the years immediately after its release, it was trumpeted at every level of the mainstream press as the herald of a new, dawning age of maturity and aesthetic sophistication in games. Then, by the end of the decade, it was lamented as a symbol of what games might have become, if only the culture of gaming had chosen it rather than the near-simultaneously-released Doom as its model for the future. Whatever the merits of that argument, the hardcore Myst lovers remained numerous enough in later years to support five sequels, a series of novels, a tabletop role-playing game, and multiple remakes and remasters of the work which began it all. Their passion was such that, when Cyan gave up on an attempt to turn Myst into a massively-multiplayer game, the fans stepped in to set up their own servers and keep it alive themselves.

And yet, for all the love it’s inspired, the game’s detractors are if anything even more committed than its proponents. For a huge swath of gamers, Myst has become the poster child for a certain species of boring, minimally interactive snooze-fest created by people who have no business making games — and, runs the spoken or unspoken corollary, played by people who have no business playing them. Much of this vitriol comes from the crowd who hate any game that isn’t violent and visceral on principle.

But the more interesting and perhaps telling brand of hatred comes from self-acknowledged fans of the adventure-game genre. These folks were usually raised on the Sierra and LucasArts traditions of third-person adventures — games that were filled with other characters to interact with, objects to pick up and carry around and use to solve puzzles, and complicated plot arcs unfolding chapter by chapter. They have a decided aversion to the first-person, minimalist, deserted, austere Myst, sometimes going so far as to say that it isn’t really an adventure game at all. But, however they categorize it, they’re happy to credit it with all but killing the adventure genre dead by the end of the 1990s. Myst, so this narrative goes, prompted dozens of studios to abandon storytelling and characters in favor of yet more sterile, hermetically sealed worlds just like its. And when the people understandably rejected this airless vision, that was that for the adventure game writ large. Some of the hatred directed toward Myst by stalwart adventure fans — not only fans of third-person graphic adventures, but, going even further back, fans of text adventures — reaches an almost poetic fever pitch. A personal favorite of mine is the description deployed by Michael Bywater, who in previous lives was himself an author of textual interactive fiction. Myst, he says, is just “a post-hippie HyperCard stack with a rather good music loop.”

After listening to the cultural dialog — or shouting match! — which has so long surrounded Myst, one’s first encounter with the actual artifact that spurred it all can be more than a little anticlimactic. Seen strictly as a computer game, Myst is… okay. Maybe even pretty good. It strikes this critic at least as far from the best or worst game of its year, much less of its decade, still less of all gaming history. Its imagery is well-composited and occasionally striking, its sound and music design equally apt. The sense of desolate, immersive beauty it all conveys can be strangely affecting, and it’s married to puzzle-design instincts that are reasonable and fair. Myst‘s reputation in some quarters as impossible, illogical, or essentially unplayable is unearned; apart from some pixel hunts and perhaps the one extended maze, there’s little to really complain about on that front. On the contrary: there’s a definite logic to its mechanical puzzles, and figuring out how its machinery works through trial and error and careful note-taking, then putting your deductions into practice, is genuinely rewarding, assuming you enjoy that sort of thing.

At the same time, though, there’s just not a whole lot of there there. Certainly there’s no deeper meaning to be found; Myst never tries to be about more than exploring a striking environment and solving intricate puzzles. “When we started, we wanted to make a [thematic] statement, but the project was so big and took so much effort that we didn’t have the energy or time to put much into that part of it,” admits Robyn Miller. “So, we decided to just make a neat world, a neat adventure, and say important things another time.” And indeed, a “neat world” and “neat adventure” are fine ways of describing Myst.

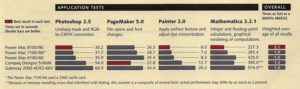

Depending on your preconceptions going in, actually playing Myst for the first time is like going to meet your savior or the antichrist, only to find a pleasant middle-aged fellow who offers to pour you a cup of tea. It’s at this point that the questions begin. Why does such an inoffensive game offend so many people? Why did such a quietly non-controversial game become such a magnet for controversy? And the biggest question of all: why did such a simple little game, made by five people using only off-the-shelf consumer software, become one of the most (in)famous money spinners in the history of the computer-games industry?

We may not be able to answers all of these whys to our complete satisfaction; much of the story of Myst surely comes down to sheer happenstance, to the proverbial butterfly flapping its wings somewhere on the other side of the world. But we can at least do a reasonably good job with the whats and hows of Myst. So, let’s consider now what brought Myst about and how it became the unlikely success it did. After that, we can return once again to its proponents and its detractors, and try to split the difference between Myst as gaming’s savior and Myst as gaming’s antichrist.

If nothing else, the origin story of Myst is enough to make one believe in karma. As I wrote in an earlier article, the Miller brothers and their company Cyan came out of the creative explosion which followed Apple’s 1987 release of HyperCard, a unique Macintosh authoring system which let countless people just like them experiment for the first time with interactive multimedia and hypertext. Cyan’s first finished project was The Manhole. Published in November of 1988 by Mediagenic, it was a goal-less software toy aimed at children, a virtual fairy-tale world to explore. Six months later, Mediagenic added music and sound effects and released it on CD-ROM, marking the first entertainment product ever to appear on that medium. The next couple of years brought two more interactive explorations for children from Cyan, published on floppy disk and CD-ROM.

Even as these were being published, however, the wheels were gradually coming off of Mediagenic, thanks to a massive patent-infringement lawsuit they lost to the Dutch electronics giant Philips and a whole string of other poor decisions and unfortunate events. In February of 1991, a young bright spark named Bobby Kotick seized Mediagenic in a hostile takeover, reverting the company to its older name of Activision. By this point, the Miller brothers were getting tired of making whimsical children’s toys; they were itching to make a real game, with a goal and puzzles. But when they asked Activision’s new management for permission to do so, they were ordered to “keep doing what you’ve been doing.” Shortly thereafter, Kotick announced that he was taking Activision into Chapter 11 bankruptcy. After he did so, Activision simply stopped paying Cyan the royalties on which they depended. The Miller brothers were lost at sea, with no income stream and no relationships with any other publishers.

But at the last minute, they were thrown an unexpected lifeline. Lo and behold, the Japanese publisher Sunsoft came along offering to pay Cyan $265,000 to make a CD-ROM-based adult adventure game in the same general style as their children’s creations — i.e., exactly what the Miller brothers had recently asked Activision for permission to do. Sunsoft was convinced that there would be major potential for such a game on the upcoming generation of CD-ROM-based videogame consoles and multimedia set-top boxes for the living room — so convinced, in fact, that they were willing to fund the development of the game on the Macintosh and take on the job of porting it to these non-computer platforms themselves, all whilst signing over the rights to the computer version(s) to Cyan for free. The Miller brothers, reduced by this point to a diet of “rice and beans and government cheese,” as Robyn puts it, knew deliverance when they saw it. They couldn’t sign the contract fast enough. Meanwhile Activision had just lost out on the chance to release what would turn out to be one of the games of the decade.

But of course the folks at Cyan were as blissfully unaware of that future as those at Activision. They simply breathed sighs of relief and started making their game. In time, Cyan signed a contract with Brøderbund to release the computer versions of their game, starting with the Macintosh original.

Myst certainly didn’t begin as any conscious attempt to re-imagine the adventure-game form. Those who later insisted on seeing it in almost ideological terms, as a sort of artistic manifesto, were often shocked when they first met the Miller brothers in person. This pair of plain-spoken, baseball-cap-wearing country boys were anything but ideologues, much less stereotypical artistes. Instead they seemed a perfect match for the environs in which they worked: an unassuming two-story garage in Spokane, Washington, far from any centers of culture or technology. Their game’s unique personality actually stemmed from two random happenstances rather than any messianic fervor.

One of these was — to put it bluntly — their sheer ignorance. Working on the minority platform that was the Macintosh, specializing up to this point in idiosyncratic children’s software, the Miller brothers were oddly disengaged from the computer-games industry whose story I’ve been telling in so many other articles here. By their own account, they had literally never even seen any of the contemporary adventure games from companies like LucasArts and Sierra before making Myst. In fact, Robyn Miller says today that he had only played one computer game in his life to that point: Infocom’s ten-year-old Zork II. Rand Miller, being the older brother, the first mover behind their endeavors, and the more technically adept of the pair, was perhaps a bit more plugged-in, but only a bit.

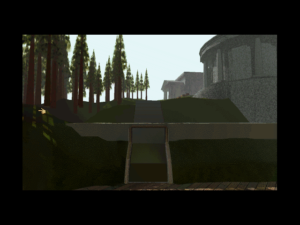

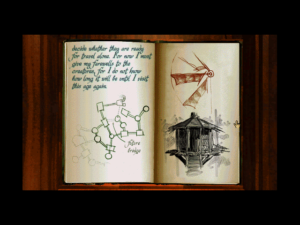

The other circumstance which shaped Myst was the technology employed to create it. This statement is true of any game, but it becomes even more salient here because the technology in question was so different from that employed by other adventure creators. Myst is indeed simply a HyperCard stack — the “hippie-dippy” is in the eye of the beholder — gluing together pictures generated by the 3D modeler StrataVision. During the second half of its development, a third everyday Macintosh software package made its mark: Apple’s QuickTime video system, which allowed Myst‘s creators to insert snippets of themselves playing the roles of the people who previously visited the semi-ruined worlds you spend the game exploring. All of these tools are presentation-level tools, not conventional game-building ones. Seen in this light, it’s little surprise that so much of Myst is surface. At bottom, it’s a giant hypertext done in pictures, with very little in the way of systems of any sort behind it, much less any pretense of world simulation. You wander through its nodes, in some of which you can click on something, which causes some arbitrary event to happen. The one place where the production does interest itself in a state which exists behind its visuals is in the handful of mechanical devices found scattered over each of its landscapes, whose repair and/or manipulation form the basis of the puzzles that turn Myst into a game rather than an unusually immersive slideshow.

In making Myst, each brother fell into the role he was used to from Cyan’s children’s projects. The brothers together came up with the story and world design, then Robyn went off to do the art and music while Rand did the technical plumbing in HyperCard. One Chuck Carter helped Robyn on the art side and Rich Watson helped Rand on the programming side, while Chris Brandkamp produced the intriguing, evocative environmental soundscape by all sorts of improvised means: banging a wrench against the wall or blowing bubbles in a toilet bowl, then manipulating the samples to yield something appropriately other-worldly. And that was the entire team. It was a shoestring operation, amateurish in the best sense. The only thing that distinguished the boys at Cyan from a hundred thousand other hobbyists playing with the latest creative tools on their own Macs was the fact that Cyan had a contract to do so — and a commensurate quantity of real, raw talent, of course.

Ironically given that Myst was treated as such a cutting-edge product at the time of its release, in terms of design it’s something of a throwback — a fact that does become less surprising when one considers that its creators’ experience with adventure games stopped in the early 1980s. A raging debate had once taken place in adventure circles over whether the ideal protagonist should be a blank slate, imprintable by the player herself, or a fully-fleshed-out role for the player to inhabit. The verdict had largely come down on the side of the latter as games’ plots had grown more ambitious, but the whole discussion had passed the Miller brothers by.

So, with Myst we were back to the old “nameless, faceless adventurer” paradigm which Sierra and LucasArts had long since abandoned. Myst actively encourages you to think of it as yourself there in its world. The story begins when you open a mysterious book here on our world, whereupon you get sucked into an alternate dimension and find yourself standing on the dock of a deserted island. You soon learn that you’re following a trail first blazed by a father and his two sons, all of whom had the ability to hop about between dimensions — or “ages,” as the game calls them — and alter them to their will. Unfortunately, the father is now said to be dead, while the two brothers have each been trapped in a separate interdimensional limbo, each blaming the other for their father’s death. (These themes of sibling rivalry have caused much comment over the years, especially in light of the fact that each brother in the game is played by one of the real Miller brothers. But said real brothers have always insisted that there are no deeper meanings to be gleaned here…)

You can access four more worlds from the central island just as soon as you solve the requisite puzzles. In each of them, you must find a page of a magical book. Putting the pages together, along with a fifth page found on the central island, allows you to free the brother of your choice, or to do… something else, which actually leads to the best ending. This last-minute branch to an otherwise unmalleable story is a technique we see in a fair number of other adventure games wishing to make a claim to the status of genuinely interactive fictions. (In practice, of course, players of those games and Myst alike simply save before the final choice and check out all of the endings.)

For all its emphasis on visuals, Myst is designed much like a vintage text adventure in many ways. Even setting aside its explicit maze, its network of discrete, mostly empty locations resembles the map from an old-school text adventure, where navigation is half the challenge. Similarly, its complex environmental puzzles, where something done in one location may have an effect on the other side of the map, smacks of one of Infocom’s more cerebral, austere games, such as Zork III or Spellbreaker.

This is not to say that Myst is a conscious throwback; the nature of the puzzles, like so much else about the game, is as much determined by the Miller brothers’ ignorance of contemporary trends in adventure design as by the technical constraints under which they labored. Among the latter was the impossibility of even letting the player pick things up and carry them around to use elsewhere. Utterly unfazed, Rand Miller coined an aphorism: “Turn your problems into features.” Thus Myst‘s many vaguely steam-punky mechanical puzzles, all switches to throw and ponderous wheels to set in motion, are dictated as much by its designers’ inability to implement a player inventory as by their acknowledged love for Jules Verne.

And yet, whatever the technological determinism that spawned it, this style of puzzle design truly was a breath of fresh air for gamers who had grown tired of the “use this object on that hotspot” puzzles of Sierra and LucasArts. To their eternal credit, the Miller brothers took this aspect of the design very seriously, giving their puzzles far more thought than Sierra at least tended to do. They went into Myst with no experience designing puzzles, and their insecurity about this aspect of their craft was perhaps their ironic saving grace. Before they even had a computer game to show people, they spent hours walking outsiders through their scenario Dungeons & Dragons-style, telling them what they saw and listening to how they tried to progress. And once they did have a working world on the computer, they spent more hours sitting behind players, watching what they did. Robyn Miller, asked in an interview shortly after the game’s release whether there was anything he “hated,” summed up thusly their commitment to consistent, logical puzzle design and world-building (in Myst, the two are largely one and the same):

Seriously, we hate stuff without integrity. Supposed “art” that lacks attention to detail. That bothers me a lot. Done by people who are forced into doing it or who are doing it for formula reasons and monetary reasons. It’s great to see something that has integrity. It makes you feel good. The opposite of that is something I dislike.

We tried to create something — a fantastic world — in a very realistic way. Creating a fantasy world in an unrealistic way is the worst type of fantasy. In Jurassic Park, the idea of dinosaurs coming to life in the twentieth century is great. But it works in that movie because they also made it believable. That’s how the idea and the execution of that idea mix to create a truly great experience.

Taken as a whole, Myst is a master class in designing around constraints. Plenty of games have been ruined by designers whose reach exceeded their core technology’s grasp. We can see this phenomenon as far back as the time of Scott Adams: his earliest text adventures were compact marvels, but quickly spiraled into insoluble incoherence when he started pushing beyond what his simplistic parsers and world models could realistically present. Myst, then, is an artwork of the possible. Managing inventory, with the need for a separate inventory screen and all the complexities of coding this portable object interacting on that other thing in the world, would have stretched HyperCard past the breaking point. So, it’s gone. Interactive conversations would have been similarly prohibitive with the technology at the Millers’ fingertips. So, they devised a clever dodge, showing the few characters that exist only as recordings, or through one-way screens where you can see them, but they can’t see (or hear) you; that way, a single QuickTime video clip is enough to do the trick. In paring things back so dramatically, the Millers wound up with an adventure game unlike any that had been seen before. Their problems really did become their game’s features.

For the most part, anyway. The networks of nodes and pre-rendered static views that constitute the worlds of Myst can be needlessly frustrating to navigate, thanks to the way that the views prioritize aesthetics over consistency; rotating your view in place sometimes turns you 90 degrees, sometimes 180 degrees, sometimes somewhere in between, according to what the designers believed would provide the most striking image. Orienting yourself and moving about the landscape can thus be a confusing process. One might complain as well that it’s a slow one, what with all the empty nodes which you must move through to get pretty much anywhere — often just to see if something you’ve done on one side of the map has had any effect on something on its other side. Again, a comparison with the twisty little passages of an old-school text adventure, filled with mostly empty rooms, does strike me as thoroughly apt.

On the other hand, a certain glaciality of pacing seems part and parcel of what Myst fundamentally is. This is not a game for the impatient. It’s rather targeted at two broad types of player: the aesthete, who will be content just to wander the landscape taking in the views, perhaps turning to a walkthrough to be able to see all of the worlds; and the dedicated puzzle solver, willing to pull out paper and pencil and really dig into the task of understanding how all this strange machinery hangs together. Both groups have expressed their love for Myst over the years, albeit in terms which could almost convince you they’re talking about two entirely separate games.

So much for Myst the artifact. What of Myst the cultural phenomenon?

The origins of the latter can be traced to the Miller brothers’ wise decision to take their game to Brøderbund. Brøderbund tended to publish fewer products per year than their peers at Electronic Arts, Sierra, or the lost and unlamented Mediagenic, but they were masterful curators, with a talent for spotting software which ordinary Americans might want to buy and then packaging and marketing it perfectly to reach them. (Their insistence on focus testing, so confusing to the Millers, is proof of their competence; it’s hard to imagine any other publisher of the time even thinking of such a thing.) Brøderbund published a string of products over the course of a decade or more which became more than just hits; they became cultural icons of their time, getting significant attention in the mainstream press in addition to the computer magazines: The Print Shop, Carmen Sandiego, Lode Runner, Prince of Persia, SimCity. And now Myst was about to become the capstone to a rather extraordinary decade, their most successful and iconic release of all.

Brøderbund first published the game on the Macintosh in September of 1993, where it was greeted with rave reviews. Not a lot of games originated on the Mac at all, so a new and compelling one was always a big event. Mac users tended to conceive of themselves as the sophisticates of the computer world, wearing their minority status as a badge of pride. Myst hit the mark beautifully here; it was the Mac-iest of Mac games. MacWorld magazine’s review is a rather hilarious example of a homer call. “It’s been polished until it shines,” wrote the magazine. Then, in the next paragraph: “We did encounter a couple of glitches and frozen screens.” Oh, well.

Helped along by press like this, Myst came out of the gates strong. By one report, it sold 200,000 copies on the Macintosh alone in its first six months. If correct or even close to correct, those numbers are extraordinary; they’re the numbers of a hit even on the gaming Mecca that was the Wintel world, much less on the Mac, with its vastly smaller user base.

Still, Brøderbund knew that Myst‘s real opportunity lay with those selfsame plebeian Wintel machines which most Mac users, the Miller brothers included, disdained. Just as soon as Cyan delivered the Mac version, Brøderbund set up an internal team — larger than the Cyan team which had made the game in the first place — to do the port as quickly as possible. Importantly, Myst was ported not to bare MS-DOS, where almost all “hardcore” games still resided, but to Windows, where the new demographics which Brøderbund hoped to attract spent all of their time. Luckily, the game’s slideshow visuals were possible even under Windows’s sluggish graphics libraries, and Apple had recently ported their QuickTime video system to Microsoft’s platform. The Windows version of Myst shipped in March of 1994.

And now Brøderbund’s marketing got going in earnest, pushing the game as the one showcase product which every purchaser of a new multimedia PC simply had to have. At the time, most CD-ROM based games also shipped in a less impressive floppy-disk-based version, with the latter often still outselling the former. But Brøderbund and Cyan made the brave choice not to attempt a floppy-disk version at all. The gamble paid off beautifully, furthering the carefully cultivated aspirational quality which already clung to Myst, now billed as the game which simply couldn’t be done on floppy disk. Brøderbund’s lush advertisements had a refined, adult air about them which made them stand out from the dragons, spaceships, and scantily-clad babes that constituted the usual motifs of game advertising. As the crowning touch, Brøderbund devised a slick tagline: Myst was “the surrealistic adventure that will become your world.” The Miller brothers scoffed at this piece of marketing-speak — until they saw how Myst was flying off the shelves in the wake of it.

So, through a combination of lucky timing and precision marketing, Myst blew up huge. I say this not to diminish its merits as a puzzle-solving adventure game, which are substantial, but simply because I don’t believe those merits were terribly relevant to the vast majority of people who purchased it. A parallel can be drawn with Infocom’s game of Zork, which similarly surfed a techno-cultural wave a decade before Myst. It was on the scene just as home computers were first being promoted in the American media as the logical, more permanent successors to the videogame-console fad. For a time, Zork, with its ability to parse pseudo-natural-English sentences, was seen by computer salespeople as the best overall demonstration of what a computer could do; they therefore showed it to their customers as a matter of course. And so, when countless new computer systems went home with their new owners, there was also a copy of Zork in the bag. The result was Infocom’s best-selling game of all time, to the tune of almost 400,000 copies sold.

Myst now played the same role in a new home-computer boom. The difference was that, while the first boom had fizzled rather quickly when people realized of what limited practical utility those early machines actually were, this second boom would be a far more sustained affair. In fact, it would become the most sustained boom in the history of the consumer PC, stretching from approximately 1993 right through the balance of the decade, with every year breaking the sales records set by the previous one. The implications for Myst, which arrived just as the boom was beginning, were titanic. Even long after it ceased to be particularly cutting-edge, it continued to be regarded as an essential accessory for every PC, to be tossed into the bags carried home from computer stores by people who would never buy another game.

Myst had already established its status by the time the hype over the World Wide Web and Windows 95 really lit a fire under computer sales in 1995. It passed the 1 million copy mark in the spring of that year. By the same point, a quickie “strategy guide” published by Prima, ideal for the many players who just wanted to take in its sights without worrying about its puzzles, had passed an extraordinary 300,000 copies sold — thus making its co-authors, who’d spent all of three weeks working on it, the two luckiest walkthrough authors in history. Defying all of the games industry’s usual logic, which dictated that titles sold in big numbers for only a few months before fizzling out, Myst‘s sales just kept accelerating from there. It sold 850,000 copies in 1996 in the United States alone, then another 870,000 copies in 1997. Only in 1998 did it finally begin to flag, posting domestic sales of just 540,000 copies. Fortunately, the European market for multimedia PCs, which lagged a few years behind the American one, was now also burning bright, opening up whole new frontiers for Myst. Its total retail sales topped 6 million by 2000, at least 2 million of them outside of North America. Still more copies — it’s impossible to say how many — had shipped as pack-in bonuses with multimedia upgrade kits and the like. Meanwhile, under the terms of Sunsoft’s original agreement with Cyan, it was also ported by the former to the Sega Saturn, Atari Jaguar, 3DO, and CD-I living-room consoles. Myst was so successful that another publisher came out with an elaborate parody of it as a full-fledged computer game in its own right, under the indelible title of Pyst. Considering that it featured the popular sitcom star John Goodman, Pyst must have cost far more to make than the shoestring production it mocked.

As we look at the staggering scale of Myst‘s success, we can’t avoid returning to that vexing question of why it all should have come to be. Yes, Brøderbund’s marketing campaign was brilliant, but there must be more to it than that. Certainly we’re far from the first to wonder about it all. As early as December of 1994, Newsweek magazine noted that “in the gimmick-dominated world of computer games, Myst should be the equivalent of an art film, destined to gather critical acclaim and then dust on the shelves.” So why was it selling better than guaranteed crowd-pleasers with names like Star Wars on their boxes?

It’s not that it’s that difficult to pinpoint some of the other reasons why Myst should have been reasonably successful. It was a good-looking game that took full advantage of CD-ROM, at a time when many computer users — non-gamers almost as much as gamers — were eager for such things to demonstrate the power of their new multimedia wundermachines. And its distribution medium undoubtedly helped its sales in another way: in this time before CD burners became commonplace, it was immune to the piracy that many publishers claimed was costing them at least half their sales of floppy-disk-based games.

Likewise, a possible explanation for Myst‘s longevity after it was no longer so cutting-edge might be the specific technological and aesthetic choices made by the Miller brothers. Many other products of the first gush of the CD-ROM revolution came to look painfully, irredeemably tacky just a couple of years after they had dazzled, thanks to their reliance on grainy video clips of terrible actors chewing up green-screened scenery. While Myst did make some use of this type of “full-motion video,” it was much more restrained in this respect than many of its competitors. As a result, it aged much better. By the end of the 1990s, its graphics resolution and color count might have been a bit lower than those of the latest games, and it might not have been quite as stunning at first glance as it once had been, but it remained an elegant, visually-appealing experience on the whole.

Yet even these proximate causes don’t come close to providing a full explanation of why this art film in game form sold like a blockbuster. There are plenty of other games of equal or even greater overall merit to which they apply equally well, but none of them sold in excess of 6 million copies. Perhaps all we can do in the end is chalk it up to the inexplicable vagaries of chance. Computer sellers and buyers, it seems, needed a go-to game to show what was possible when CD-ROM was combined with decent graphics and sound cards. Myst was lucky enough to become that game. Although its puzzles were complex, simply taking in its scenery was disarmingly simple, making it perfect for the role. The perfect product at the perfect time, perfectly marketed.

In a sense, Myst the phenomenon didn’t do that other Myst — Myst the actual artifact, the game we can still play today — any favors at all. The latter seems destined always to be judged in relation to the former, and destined always to be found lacking. Demanding that what is in reality a well-designed, aesthetically pleasing game live up to the earth-shaking standards implied by Myst‘s sales numbers is unfair on the face of it; it wasn’t the fault of the Miller brothers, humble craftsmen with the right attitude toward their work, that said work wound up selling 6 million copies. Nevertheless, we feel compelled to judge it, at least to some extent, with the knowledge of its commercial and cultural significance firmly in mind. And in this context especially, some of its detractors’ claims do have a ring of truth.

Arguably the truthiest of all of them is the oft-repeated old saw that no other game was bought by so many people and yet really, seriously played by so few of its purchasers. While such a hyperbolic claim is impossible to truly verify, there is a considerable amount of circumstantial evidence pointing in exactly that direction. The exceptional sales of the strategy guide are perhaps a wash; they can be as easily ascribed to serious players wanting to really dig into the game as they can to casual purchasers just wanting to see all the pretty pictures on the CD-ROM. Other factors, however, are harder to dismiss. The fact is, Myst is hard by casual-game standards — so hard that Brøderbund included a blank pad of paper in the box for the purpose of keeping notes. If we believe that all or most of its buyers made serious use of that notepad, we have to ask where these millions of people interested in such a cerebral, austere, logical experience were before it materialized, and where they went thereafter. Even the Miller brothers themselves — hardly an unbiased jury — admit that by their best estimates no more than 50 percent of the people who bought Myst ever got beyond the starting island. Personally, I tend to suspect that the number is much lower than that.

Perhaps the most telling evidence for Myst as the game which everyone had but hardly anyone played is found in a comparison with one of its contemporaries: id Software’s Doom, the other decade-dominating blockbuster of 1993 (a game about which I’ll be writing much more in a future article). Doom indisputably was played, and played extensively. While it wasn’t quite the first running-around-and-shooting-things-from-a-first-person-perspective game, it did become so popular that games of its type were codified as a new genre unto themselves. The first-person shooters which followed Doom in the 1990s were among the most popular games of their era. Many of their titles are known to gamers today who weren’t yet born when they debuted: titles like Duke Nukem 3D, Quake, Half-Life, Unreal. Myst prompted just as many copycats, but these were markedly less popular and are markedly less remembered today: AMBER: Journeys Beyond, Zork Nemesis, Rama, Obsidian. Only Cyan’s own eventual sequel to Myst can be found among the decade’s bestsellers, and even it’s a definite case of diminishing commercial returns, despite being a rather brilliant game in its own right. In short, any game which sold as well as Myst, and which was seriously played by a proportionate number of people, ought to have left a bigger imprint on ludic culture than this one did.

But none of this should affect your decision about whether to play Myst today, assuming you haven’t yet gotten around to it. Stripped of all its weighty historical context, it’s a fine little adventure game if not an earth-shattering one, intriguing for anyone with the puzzle-solving gene, infuriating for anyone without it. You know what I mean… sort of a niche experience. One that just happened to sell 6 million copies.

(Sources: the books Myst: Prima’s Official Strategy Guide by Rick Barba and Rusel DeMaria, Myst & Riven: The World of the D’ni by Mark J.P. Wolf, and The Secret History of Mac Gaming by Richard Moss; Computer Gaming World of December 1993; MacWorld of March 1994; CD-ROM Today of Winter 1993. Online sources include “Two Histories of Myst” by John-Gabriel Adkins, Ars Technica‘s interview with Rand Miller, Robyn Miller’s postmortem of Myst at the 2013 Game Developers Conference, GameSpot‘s old piece on Myst as one of the “15 Most Influential Games of All Time,” and Greg Lindsay’s Salon column on Myst as a “dead end.” Michael Bywater’s colorful comments about Myst come from Peter Verdi’s now-defunct Magnetic Scrolls fan site, a dump of which Stefan Meier dug up for me from his hard drive several years ago. Thanks again, Stefan!

The “Masterpiece Edition” of Myst is available for purchase from GOG.com.)