This series of articles so far has been a story of business-oriented personal computing. Corporate America had been running for decades on IBM before the IBM PC appeared, so it was only natural that the standard IBM introduced would be embraced as the way to get serious, businesslike things done on a personal computer. Yet long before IBM entered the picture, personal computing in general had been pioneered by hackers and hobbyists, many of whom nursed grander dreams than giving secretaries a better typewriter or giving accountants a better way to add up figures. These pioneers didn’t go away after 1981, but neither did they embrace the IBM PC, which most of them dismissed as technically unimaginative and aesthetically disastrous. Instead they spent the balance of the 1980s using computers like the Apple II, the Commodore 64, the Commodore Amiga, and the Atari ST to communicate with one another, to draw pictures, to make music, and of course to write and play lots and lots of games. Dwarfed already in terms of dollars and cents at mid-decade by the business-computing monster the IBM PC had birthed, this vibrant alternative computing ecosystem — sometimes called home computing, sometimes consumer computing — makes a far more interesting subject for the cultural historian of today than the world of IBM and Microsoft, with its boring green screens and boring corporate spokesmen running scared from the merest mention of digital creativity. It’s for this reason that, a few series like this one aside, I’ve spent the vast majority of my time on this blog talking about the cultures of creative computing rather than those of IBM and Microsoft.

Consumer computing did enjoy one brief boom in the 1980s. From roughly 1982 to 1984, a narrative took hold within the mainstream media and the offices of venture capitalists alike that full-fledged computers would replace the Atari VCS and other game consoles in American homes on a massive scale. After all, computers could play games just like the consoles, but they alone could also be used to educate the kids, write school reports and letters, balance the checkbook, and — that old favorite to which the pundits returned again and again — store the family recipes.

All too soon, though, the limitations of the cheap 8-bit computers that had fueled the boom struck home. As a consumer product, those early computers with their cryptic blinking command prompts were hopeless; at least with an Atari VCS you could just put a cartridge in the slot, turn it on, and play. There were very few practical applications for which they weren’t more trouble than they were worth. If you needed to write a school report, a standalone word-processing machine designed for that purpose alone was often a cheaper and better solution, and the family accounts and recipes were actually much easier to store on paper than in a slow, balky computer program. Certainly paper was the safer choice over a pile of fragile floppy disks.

So, what we might call the First Home Computer Revolution fizzled out, with most of the computers that had been purchased over its course making the slow march of shame from closet to attic to landfill. That minority who persisted with their new computers was made up of the same sorts of personalities who had had computers in their homes before the boom — for the one concrete thing the First Home Computer Revolution had achieved was to make home computers in general more affordable, and thus put them within the reach of more people who were inclined toward them anyway. People with sufficient patience continued to find home computers great for playing games that offered more depth than the games on the consoles, while others found them objects of wonder unto themselves, new oceans just waiting to have their technological depths plumbed by intrepid digital divers. It was mostly young people, who had free time on their hands, who were open to novelty, who were malleable enough to learn something new, and who were in love with escapist fictions of all stripes, who became the biggest home-computer users.

Their numbers grew at a modest pace every year, but the real money, it was now clear, was in business computing. Why try to sell computers piecemeal to teenagers when you could sell them in bulk to corporations? IBM, after having made one abortive stab at capturing home computing as well via the ill-fated PCjr, went where the money was, and all but a few other computer makers — most notable among these home-computer loyalists were Commodore, Atari, and Radio Shack — followed them there. The teenagers, for their part, responded to the business-computing majority’s contempt in kind, piling scorn onto the IBM PC’s ludicrously ugly CGA graphics and its speaker that could do little more than beep and fart at you, all while embracing their own more colorful platforms with typical adolescent zeal.

As the 1980s neared their end, however, the ugly old MS-DOS computer started down an unanticipated road of transformation. In 1987, as part of the misbegotten PS/2 line, IBM introduced a new graphics standard called VGA that, with up to 256 onscreen colors from a palette of more than 260,000, outdid all of the common home computers of the time. Soon after, enterprising third parties like Ad Lib and Creative Labs started making add-on sound cards for MS-DOS machines that could make real music and — just as important for game fanatics — real explosions. Many a home hacker woke up one morning to realize that the dreaded PC clone suddenly wasn’t looking all that bad. No, the technical architecture wasn’t beautiful, but it was robust and mature, and the pressure of having dozens of competitors manufacturing machines meeting the standard kept the bang-for-your-buck ratio very good. And if you — or your parents — did want to do any word processing or checkbook balancing, the software for doing so was excellent, honed by years of catering to the most demanding of corporate users. Ditto the programming tools that were nearer to a hacker’s heart; Borland’s Turbo Pascal alone was a thing of wonder, better than any other programming environment on any other personal computer.

Meanwhile 8-bit home computers like the Apple II and the Commodore 64 were getting decidedly long in the tooth, and the companies that made them were doing a peculiarly poor job of replacing them. The Apple Macintosh was so expensive as to be out of reach of most, and even the latest Apple II, known as the IIGS, was priced way too high for what it was; Apple, having joined the business-computing rat race, seemed vaguely embarrassed by the continuing existence of the Apple II, the platform that had made them. The Commodore Amiga 500 was perhaps a more promising contender to inherit the crown of the Commodore 64, but its parent company had mismanaged their brand almost beyond hope of redemption in the United States.

So, in 1988 and 1989 MS-DOS-based computing started coming home, thanks both to its own sturdy merits and a lack of compelling alternatives from the traditional makers of home computers. The process was helped along by Sierra Online, a major publisher of consumer software who had bet big and early on the MS-DOS standard conquering the home in the end, and were thus out in front of its progress now with a range of appealing games that took full advantage of the new graphics and sound cards. Other publishers, reeling before a Nintendo onslaught that was devastating the remnants of the 8-bit software market, soon followed their lead. By 1990, the vast majority of the American consumer-software industry had joined their counterparts in business software in embracing MS-DOS as their platform of first — often, of only — priority.

Bill Gates had always gone where the most money was. In years past, the money had been in business computing, and so Microsoft, after experimenting briefly with consumer software in the period just before the release of the IBM PC, had all but ignored the consumer market in favor of system software and applications targeted squarely at corporate America. Now, though, the times were changing, as home computers became powerful and cheap enough to truly go mainstream. The media was buzzing about the subject as they hadn’t for years; everywhere it was multimedia this, CD-ROM that. Services like Prodigy and America Online were putting a new, friendlier face on the computer as a tool for communicating and socializing, and game developers were buzzing about an emerging new form of mass-market entertainment, a merger of Silicon Valley and Hollywood. Gates wasn’t alone in smelling a Second Home Computer Revolution in the wind, one that would make the computer a permanent fixture of modern American home life in all the ways the first had failed to do so.

This, then, was the zeitgeist into which Microsoft Windows 3.0 made its splashy debut in May of 1990. It was perfectly positioned both to drive the Second Home Computer Revolution and to benefit from it. Small wonder that Microsoft undertook a dramatic branding overhaul this year, striving to project a cooler, more entertaining image — an image appropriate for a company which marketed not to other companies but to individual consumers. One might say that the Microsoft we still know today was born on May 22, 1990, when Bill Gates strode onto a stage — tellingly, not a stage at Comdex or some other stodgy business-oriented computing event — to introduce the world to Windows 3.0 over a backdrop of confetti cannons, thumping music, and huge projection screens.

The delirious sales of Windows 3.0 that followed were not — could not be, given their quantity — driven exclusively by sales to corporate America. The world of computing had turned topsy-turvy; consumer computing was where the real action was now. Even as they continued to own business-oriented personal computing, Microsoft suddenly dominated in the home as well, thanks to the capitulation without much of a fight of all of the potential rivals to MS-DOS and Windows. Countless copies of Windows 3.0 were sold by Microsoft directly to Joe Public to install on his existing home computer, through a toll-free hotline they set up for the purpose. (“Have your credit card ready and call!”) Even more importantly, as new computers entered American homes in mass quantities for the second time in history, they did so with Windows already on their hard drives, thanks to Microsoft’s longstanding deals with the companies that made them.

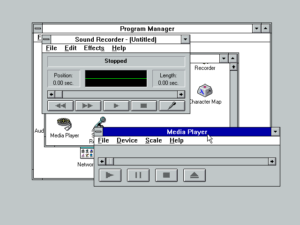

In April of 1992, Windows 3.1 appeared, sporting as one of its most important new features a set of “multimedia extensions” — this meaning tools for recording and playing back sounds, for playing audio CDs, and, most of all, for running a new generation of CD-ROM-based software sporting digitized voices and music and video clips — which were plainly aimed at the home rather than the business user. Although Windows 3.1 wasn’t as dramatic a leap forward as its predecessor had been, Microsoft nevertheless hyped it to the skies in the mass media, rolling out an $8 million television-advertising campaign among other promotional strategies that would have been unthinkable from the business-focused Microsoft of just a few years earlier. It sold even faster than had its predecessor.

A Quick Tour of Windows for Workgroups 3.1

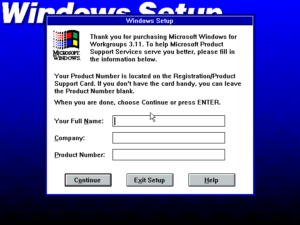

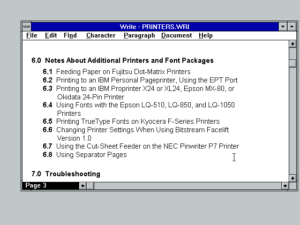

Released in April of 1992, Windows 3.1 was the ultimate incarnation of Windows’s third generation. (A version 3.11 was released the following year, but it confined itself to bug fixes and modest performance tweaks, introducing no significant new features.) It dropped support for 8088-based machines, and with it the old “real mode” of operation; it now ran only in protected mode or 386 enhanced mode. It made welcome strides in terms of stability, even as it still left much to be desired on that front. And this Windows was the last to be sold as an add-on to an MS-DOS which had to be purchased separately. Consumer-grade incarnations of Windows would continue to be built on top of MS-DOS for the rest of the decade, but from Windows 95 on Microsoft would do a better job of hiding their humble foundation by packaging the whole software stack together as a single product.

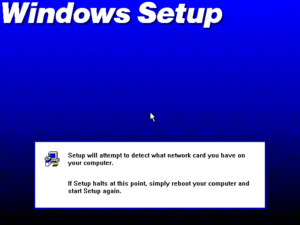

Stuff like this is the reason Windows always took such a drubbing in comparison to other, slicker computing platforms. In truth, Microsoft was doing the best they could to support a bewildering variety of hardware, a problem with which vendors of turnkey systems like Apple didn’t have to contend. Still, it’s never a great look to have to tell your customers, “If this crashes your computer, don’t worry about it, just try again.” Much the same advice applied to daily life with Windows, noted the scoffers.

Microsoft was rather shockingly lax about validating Windows 3 installations. The product had no copy protection of any sort, meaning one person in a neighborhood could (and often did) purchase a copy and share it with every other house on the block. Others in the industry had a sneaking suspicion that Microsoft really didn’t mind that much if Windows was widely pirated among their non-business customers — that they’d rather people run pirated copies of Windows than a competing product. It was all about achieving the ubiquity which would open the door to all sorts of new profit potential through the sale of applications. And indeed, Windows 3 was pirated like crazy, but it also became thoroughly ubiquitous. As for the end to which Windows’s ubiquity was the means: by the time applications came to represent 25 percent of Microsoft’s unit sales, they already accounted for 51 percent of their revenue. Bill Gates always had an instinct for sniffing out where the money was.

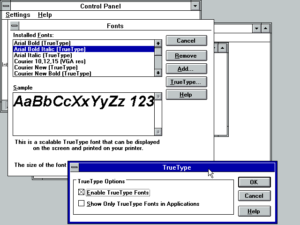

Probably the most important single enhancement in Windows 3.1 was its TrueType fonts. The rudimentary bitmap fonts which shipped with older versions looked… not all that nice on the screen or on the page, reportedly due to Bill Gates’s adamant refusal to pay a royalty for fonts to an established foundry like Adobe, as Apple had always done. This decision led to a confusion of aftermarket fonts in competing formats. If you used some of these more stylish fonts in a document, you couldn’t share that document with anyone else unless she also had installed the same fonts. So, you could either share ugly documents or keep nice-looking ones to yourself. Some choice! Thankfully, TrueType came along to fix all that, giving Macintosh users at least one less thing to laugh at when it came to Windows.

The TrueType format was the result of an unusual cooperative project led by Microsoft and Apple — yes, even as they were battling one another in court. The system of glyphs and the underlying technology to render them were intended to break the stranglehold Adobe Systems enjoyed over high-end printing; Adobe charged a royalty of up to $100 per gadget that employed their own PostScript font system, and were widely seen in consequence as a retrograde force holding back the entire desktop-publishing and GUI ecosystem. TrueType would succeed splendidly in its monopoly-busting goal, to such an extent that it remains the standard for fonts on Microsoft Windows and Apple’s OS X to this day. Bill Gates, no stranger to vindictiveness, joked that “we made [the widely disliked Adobe head] John Warnock cry.”

The other big addition to Windows 3.1 was the “multimedia extensions.” These let you do things like record sounds using an attached microphone and play your audio CDs on your computer. That they were added to what used to be a very businesslike operating environment says much about how important home users had become to Microsoft’s strategy.

In a throwback to an earlier era of computing, MS-DOS still shipped with a copy of BASIC included, and Windows 3.1 automatically found it and configured it for easy access right out of the box — this even though home computing was now well beyond the point where most users would ever try to become programmers. Bill Gates’s sentimental attachment to BASIC, the language on which he built his company before the IBM PC came along, has often been remarked upon by his colleagues, especially since he wasn’t normally a man given to much sentimentality. It was the widespread perception of Borland’s Turbo Pascal as the logical successor to BASIC — the latest great programming tool for the masses — that drove the longstanding antipathy between Gates and Borland’s flamboyant leader, Philippe Kahn. Later, it was supposedly at Gates’s insistence that Microsoft’s Visual BASIC, a Pascal-killer which bore little resemblance to BASIC as most people knew it, nevertheless bore the name.

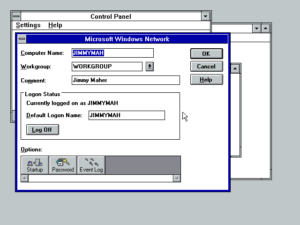

Windows for Workgroups — a separate, pricier version of the environment aimed at businesses — was distinguished by having built-in support for networking. This wasn’t, however, networking as we think of it today. It was rather intended to connect machines together only in a local office environment. No TCP/IP stack — the networking technology that powers the Internet — was included.

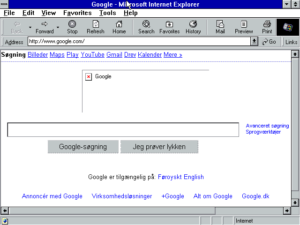

But you could get on the Internet with the right additional software. Here, just for fun, I’m trying to browse the web using Internet Explorer 5 from 1999, the last version made for Windows 3. Google is one of the few sites that work at all — albeit, as you can see, not very well.

All this success — this reality of a single company now controlling almost all personal computing, in the office and in the home — brought with it plenty of blowback. The metaphor of Microsoft as the Evil Empire, and of Bill Gates as the computer industry’s very own Darth Vader, began in earnest in these years of Windows 3’s dominance. Neither Gates nor his company had ever been beloved among their peers, having always preferred making money to making friends. Now, though, the naysayers came out in force. Bob Metcalfe, a Xerox PARC alum famous in hacker lore as the inventor of the Ethernet networking protocol, talked about Microsoft’s expanding “death grip” on innovation in the computer industry. Indeed, zombie imagery was prevalent among many of Microsoft’s rivals; Mitch Kapor of Lotus called the new Windows-driven industry “the kingdom of the dead”: “The revolution is over, and free-wheeling innovation in the software industry has ground to a halt.” Any number of anonymous commenters mused about doing Gates any number of forms of bodily harm. “It’s remarkable how widespread the negative feelings toward Microsoft are,” mused Stewart Alsop. “No one wants to work with Microsoft anymore,” said noted Gates-basher Phillipe Kahn of Borland. “We sure won’t. They don’t have any friends left.” Channeling such sentiments, Business Month magazine cropped his nerdy face onto a body-builder’s body and labeled him the “Silicon Bully” on its cover: “How long can Bill Gates kick sand in the face of the computer industry?”

Setting aside the jealousy that always follows great success, even setting aside for the moment the countless ways in which Microsoft really did play hardball with their competitors, something about Bill Gates rubbed many people the wrong way on a personal, visceral level. In keeping with their new, consumer-friendly image, Microsoft had hired consultants to fix up his wardrobe and work on his speaking style — not to mention to teach him the value of personal hygiene — and he could now get through a canned presentation ably enough. When it came to off-the-cuff interactions, though, he continued to strike many as insufferable. To judge him on the basis of his weedy physique and nasally speaking voice — the voice of the kid who always had to show how smart he was to the rest of the class — was perhaps unfair. But one certainly could find him guilty of a thoroughgoing lack of graciousness.

His team of PR coaches could have told him that, when asked who had contributed the most to the personal-computer revolution, he ought to politely decline to answer, or, even better, modestly reflect on the achievements of someone like his old friend Steve Jobs. But they weren’t in the room with him one day when that exact question was put to him by a smiling reporter, and so, after acknowledging that it really should be answered by “others less biased than me,” he proceeded to make the case for himself: “I will say that I started the first microcomputer-software company. I put BASIC in micros before 1980. I was influential in making the IBM PC a 16-bit machine. My DOS is in 50 million computers. I wrote software for the Mac.” I, I, I. Everything he said was true, at least if one presumed that “I” meant “Bill Gates and the others at Microsoft” in this context. Yet there was something unappetizing about this laundry list of achievements he could so easily rattle off, and about the almost pathological competitiveness it betrayed. We love to praise ambition in the abstract, but most of us find such naked ambition as that constantly displayed by Gates profoundly off-putting. The growing dislike for Microsoft in the computer industry and even in much of the technology press was fueled to a large extent by a personal aversion to their founder.

Which isn’t to say that there weren’t valid grounds for concern when it came to Microsoft’s complete dominance of personal-computer system software. Comparisons to the Standard Oil trust of the Gilded Age were in the air, so much so that by 1992 it was already becoming ironically useful for Microsoft to keep the Macintosh and OS/2 alive and allow them their paltry market share, just so the alleged monopolists could point to a couple of semi-viable competitors to Windows. It was clear that Microsoft’s ambitions didn’t end with controlling the operating system installed on the vast majority of computers in the country and, soon, the world. On the contrary, that was only a means to their real end. They were already using their status as the company that made Windows to cut deep into the application market, invading territory that had once belonged to the likes of Lotus 1-2-3 and WordPerfect. Now, those names were slowly being edged out by Microsoft Excel and Microsoft Word. Microsoft wanted to own more or less all of the software on your computer. Any niche outside developers that remained in computing’s new order, it seemed, would do so at Microsoft’s sufferance. The established makers of big-ticket business applications would have been chilled if they had been privy to the words spoken by Mike Maples, Microsoft’s head of applications, to his own people: “If someone thinks we’re not after Lotus and after WordPerfect and after Borland, they’re confused. My job is to get a fair share of the software applications market, and to me that’s 100 percent.” This was always the problem with Microsoft. They didn’t want to compete in the markets they entered; they wanted to own them.

Microsoft’s control of Windows gave them all sorts of advantages over other application developers which may not have been immediately apparent to the non-technical public. Take, for instance, the esoteric-sounding technology of Object Linking and Embedding, or OLE, which debuted with Windows 3.0 and still exists in current versions. OLE allows applications to share all sorts of dynamic data between themselves. Thanks to it, a word-processor document can include charts and graphs from a spreadsheet, with the one updating itself automatically when the other gets updated. Microsoft built OLE support into new versions of Word and Excel that accompanied Windows 3.0’s release, but refused for many months to tell outside developers how to use it. Thus Microsoft’s applications had hugely desirable capabilities which their competitors did not for a long, long time. Similar stories played out again and again, driving the competition to distraction while Bill Gates shrugged his shoulders and played innocent. “We bend over backwards to make sure we’re not getting special advantage,” he said, while Steve Ballmer talked about a “Chinese wall” between Microsoft’s application and system programmers — a wall which people who had actually worked there insisted simply didn’t exist.

On March 1, 1991, news broke that the Federal Trade Commission was investigating Microsoft for anti-trust violations and monopolistic practices. The investigators specifically pointed to that agreement with IBM that had been announced at the Fall 1989 Comdex, to target low-end computers with Microsoft’s Windows and high-end computers with the two companies’ joint operating system OS/2 — ironically, an “anti-competitive” initiative that Microsoft had never taken all that seriously. Once the FTC started digging, however, they found that there was plenty of other evidence to be turned up, from both the previous decade and this new one.

There was, for instance, little question that Microsoft had always leveraged their status as the maker of MS-DOS in every way they could. When Windows 3.0 came out, they helped to ensure its acceptance by telling hardware makers that the only way they would continue to be allowed to buy MS-DOS for pre-installation on their computers was to buy Windows and start pre-installing that too. Later, part of their strategy for muscling into the application market was to get Microsoft Works, a stripped-down version of the full Microsoft Office suite, pre-installed on computers as well. How many people were likely to go out and buy Lotus 1-2-3 or WordPerfect when they already had similar software on their computer? Of course, if they did need something more powerful, said the little card included with every computer, they could have the more advanced version of Microsoft Works for the cost of a nominal upgrade fee…

And there were other, far more nefarious stories to tell. There was, for instance, the tale of DR-DOS, a 1988 alternative to MS-DOS from Digital Research which was compatible with Microsoft’s operating system but offered a lot of welcome enhancements. Microsoft went after any clone maker who tried to offer DR-DOS pre-installed on their machines with both carrots (they would undercut Digital Research’s price to the point of basically giving MS-DOS away if necessary) and sticks (they would refuse to license them the upcoming, hotly anticipated Windows 3.0 if they persisted in their loyalty to Digital Research). Later, once the DR-DOS threat had been quelled, most of the features that had made it so desirable turned up in the next release of MS-DOS. Digital Research — a company which Bill Gates seemed to delight in tormenting — had once again been, in the industry’s latest parlance, “Microslimed.”

But Digital Research was neither the first nor the last such company. Microsoft, it was often claimed, had a habit of negotiating with smaller companies under false pretenses, learning what made their technology tick under the guise of due diligence, and then launching their own product based on what they had learned. In early 1990, Microsoft told Intuit, a maker of a hugely successful money-management package called Quicken, that they were interested in acquiring them. After several weeks of negotiations, including lots of discussions about how Quicken was programmed, how it was used in the wild, and what marketing strategies had been most effective, Microsoft abruptly broke off the talks, saying they “couldn’t find a way to make it work.” Before the end of 1990, they had announced Microsoft Money, their own money-management product.

More and more of these types of stories were being passed around. A startup who called themselves Go came to Microsoft with a pen-based computing interface. (The latter was all the rage at the time; Apple as well was working on something called the Newton, a sort of pen-based proto-iPad that, like all of the other initiatives in this direction, would turn into an expensive failure.) After spending weeks examining Go’s technology, Microsoft elected not to purchase it or sign them to a contract. But, just days later, they started an internal project to create a pen-based interface for Windows, headed by the engineer who had been in charge of “evaluating” Go’s technology. A meme was emerging, by no means entirely true but perhaps not entirely untrue either, of Microsoft as a company better at doing business than doing technology, who would prefer to copy the innovations of others than do the hard work of coming up with their own ideas.

In a way, though, this very quality was a source of strength for Microsoft, the reason that corporate clients flocked to them now like they once had to IBM; the mantra that “no one ever got fired for buying IBM” was fast being replaced in corporate America by “no one ever got fired for buying Microsoft.” “We don’t do innovative stuff, like completely new revolutionary stuff,” Bill Gates admitted in an unguarded moment. “One of the things we are really, really good at doing is seeing what stuff is out there and taking the right mix of good features from different products.” For businesses and, now, tens of millions of individual consumers, Microsoft really was the new IBM: they were safe. You bought a Windows machine not because it was the slickest or sexiest box on the block but because you knew it was going to be well-supported, knew there would be software on the shelves for it for a long time to come, knew that when you did decide to upgrade the transition would be a relatively painless one. You didn’t get that kind of security from any other platform. If Microsoft’s business practices were sometimes a little questionable, even if Windows crashed sometimes or kept on running inexplicably slower the longer you had it on your computer, well, you could live with that. Alan Boyd, an executive at Microsoft for a number of years:

Does Bill have a vision? No. Has he done it the right way? Yes. He’s done it by being conservative. I mean, Bill used to say to me that his job is to say no. That’s his job.

Which is why I can understand [that] he’s real sensitive about that. Is Bill innovative? Yes. Does he appear innovative? No. Bill personally is a lot more innovative than Microsoft ever could be, simply because his way of doing business is to do it very steadfastly and very conservatively. So that’s where there’s an internal clash in Bill: between his ability to innovate and his need to innovate. The need to innovate isn’t there because Microsoft is doing well. And innovation… you get a lot of arrows in your back. He lets things get out in the market and be tried first before he moves into them. And that’s valid. It’s like IBM.

Of course, the ethical problem with this approach to doing business was that it left no space for the little guys who actually had done the hard work of innovating the technologies which Microsoft then proceeded to co-opt. “Seeing what stuff is out there and taking it” — to use Gates’s own words against him — is a very good way indeed to make yourself hated.

During the 1990s, Windows was widely seen by the tech intelligentsia as the archetypal Microsoft product, an unimaginative, clunky amalgam of other people’s ideas. In his seminal (and frequently hilarious) 1999 essay “In the Beginning… Was the Command Line,” Neal Stephenson described operating systems in terms of vehicles. Windows 3 was a moped in this telling, “a Rube Goldberg contraption that, when bolted onto a three-speed bicycle [MS-DOS], enabled it to keep up, just barely, with Apple-cars. The users had to wear goggles and were always picking bugs out of their teeth while Apple owners sped along in hermetically sealed comfort, sneering out the windows. But the Micro-mopeds were cheap, and easy to fix compared with the Apple-cars, and their market share waxed.”

And yet if we wished to identify one Microsoft product that truly was visionary, we could do worse than boring old ramshackle Windows. Bill Gates first put his people to work on it, we should remember, before the original IBM PC and the first version of MS-DOS had even been released — so strongly did he believe even then, just as much as that more heralded visionary Steve Jobs, that the GUI was the future of computing. By the time Windows finally reached the market four years later, it had had occasion to borrow much from the Apple Macintosh, the platform with which it was doomed always to be unfavorably compared. But Windows 1 also included vital features of modern computing that the Mac did not, such as multitasking and virtual memory. No, it didn’t take a genius to realize that these must eventually make their way to personal computers; Microsoft had fine examples of them to look at from the more mature ecosystems of institutional computing, and thus could be said, once again, to have implemented and popularized but not innovated them.

Still, we should save some credit for the popularizers. Apple, building upon the work done at Xerox, perfected the concept of the GUI to such an extent in LisaOS and MacOS that one could say that all of the improvements made to it since have been mere details. But, entrenched in a business model that demanded high profit margins and proprietary hardware, they were doomed to produce luxury products rather than ubiquitous ones. This was the logical flaw at the heart of the much-discussed “1984” television advertisement and much of the rhetoric that continued to surround the Macintosh in the years that followed. If you want to change the world through better computing, you have to give the people a computer they can afford. Thanks to Apple’s unwillingness or inability to do that, it was Microsoft that brought the GUI to the world in their stead — in however imperfect a form.

The rewards for doing so were almost beyond belief. Microsoft’s revenues climbed by roughly 50 percent every year in the few years after the introduction of Windows 3.0, as the company stormed past Boeing to become the biggest corporation in the Pacific Northwest. Someone who had invested $1000 in Microsoft in 1986 would have seen her investment grow to $30,000 by 1991. By the same point, over 2000 employees or former employees had become millionaires. In 1992, Bill Gates was anointed by Forbes magazine the richest person in the world, a distinction he would enjoy for the next 25 years by most reckonings. The man who had been so excited when his company grew to be bigger than Lotus in 1987 now owned a company that was larger than the next five biggest software publishers combined. And as for Lotus alone? Well, Microsoft was now over four times their size. And the Decade of Microsoft had only just begun.

In 2000, the company’s high-water point, an astonishing 97 percent of all consumer computing devices would have some sort of Microsoft software installed on them. In the vast majority of cases, of course, said software would include Microsoft Windows. There would be all sorts of grounds for concern about this kind of dominance even had it not been enjoyed by a company with such a reputation for playing rough as Microsoft. (Or would a company that didn’t play rough ever have gotten to be so dominant in the first place?) In future articles, we’ll be forced to spend a lot more time dealing with Microsoft’s various scandals and controversies, along with reactions to them that took the form of legal challenges from the American government and the European Union and the rise of an alternative ideology of software called the open-source movement.

But, as we come to the end of this particular series of articles on the early days of Windows, we really should give Bill Gates some credit as well. Had he not kept doggedly on with Windows in the face of a business-computing culture that for years wanted nothing to do with it, his company could very easily have gone the way of VisiCorp, Lotus, WordPerfect, Borland, and, one might even say, IBM and Apple for a while: a star of one era of computing that was unable to adapt to the changing times. Instead, by never wavering in his belief that the GUI was computing’s future, Gates conquered the world. That he did so while still relying on the rickety foundation of MS-DOS is, yes, kind of appalling for anyone who values clean, beautiful computer engineering. Yet it also says much about his programmers’ creativity and skill, belying any notion of Microsoft as a place bereft of such qualities. Whatever else you can say about the sometimes shaky edifices that were Windows 3 and its next few generations of successors, the fact that they worked at all was something of a minor miracle.

Most of all, we should remember the huge role that Windows played in bringing computing home once again — and, this time, permanently. The third generation of Microsoft’s GUI arrived at the perfect time, just when the technology and the culture were ready for it. Once a laughingstock, Windows became for quite some time the only face of computing many people knew — in the office and in the home. Who could have dreamed it? Perhaps only one person: a not particularly dreamy man named Bill Gates.

(Sources: the books Hard Drive: Bill Gates and the Making of the Microsoft Empire by James Wallace and Jim Erickson, Gates: How Microsoft’s Mogul Reinvented an Industry and Made Himself the Richest Man in America by Stephen Manes and Paul Andrews, and In the Beginning… Was the Command Line by Neal Stephenson; Computer Power User of October 2004; InfoWorld of May 20 1991 and January 31 1994. Finally, I owe a lot to Nathan Lineback for the histories, insights, comparisons, and images found at his wonderful online “GUI Gallery.”)