When I was sitting in my office in my surf trunks, barefoot, playing ball with the dog every twenty minutes, writing the pilot for The X-Files, I never imagined that they would be making X-Files underwear and that 10,000 people a week would be logging onto the Internet to talk about the show…

— Chris Carter, 1995

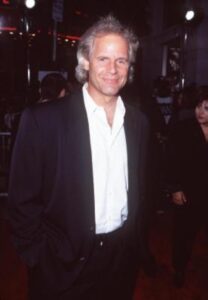

Chris Carter, the creator of The X-Files, couldn’t have been more different from your stereotypical scrawny, pasty-skinned, basement-dwelling conspiracy theorist. Born in 1956 in a suburb of Los Angeles, he was more like your stereotypical beach bum, who learned to surf almost before he learned to walk. Upon graduating from university with a degree in journalism, he went to work for Surfing magazine, rising to the post of senior editor while still in his mid-twenties. “I went around the world surfing,” he says. It was in every way a charmed life for a young man.

Not long after getting married in 1983, however, he started to think about finding a less travel-intensive career, one that might be able to sustain him even after his hardcore surfing days were behind him. He decided to try his hand at screenwriting; he was certainly living in the right part of the world for it, after all. And once again, he proved lucky or talented at his chosen profession — or, more likely, both. He broke into the business in remarkably short order, writing scripts for various TV movies along with other piecework. His longest-lasting gig was in the writers’ room of Rags to Riches, a quirky but wholesome hybrid of musical, sitcom, and family drama that ran for two seasons on NBC in 1987 and 1988. Such light-hearted, borderline saccharine material gave no hint that he had something like The X-Files in him. “I actually became known as a comedy writer,” he says. “That’s what people kept wanting me to write.”

It’s a longstanding truism in television that every workaday writer in the field dreams secretly — or not so secretly — of having a show all his own. Chris Carter was no exception. He thought his best chance of fulfilling his dream lay at Rupert Murdoch’s new Fox network, an upstart that was trying to claw out a space for itself alongside CBS, NBC, and ABC, the Big Three in American broadcast television ever since the era of the idiot box began. Fox had enjoyed its greatest success to date with programming that was a little too edgy for the stodgier established networks, but which the advertiser-coveted younger demographics adored. Shows like the rapier-witted adult-oriented cartoon The Simpsons and the decidedly non-wholesome family sitcom Married… with Children were the necessary antidote to NBC’s sugary-sweet Cosby Show, the biggest program of all on American television. Carter thought that a horror series might fit in well with the Fox lineup.

As has been recounted many times over the years since, the inspiration that started Carter down the road to The X-Files was a television obscurity from 1974, a series called Kolchak: The Night Stalker that had been allowed just one season of twenty episodes on ABC before it was cancelled. Despite its short run, its tales of a lone Chicago journalist exploring an underworld of vampires, werewolves, and other things that go bump in the night, whilst dealing with an almost equally unfriendly city government that didn’t want any of his horrifying discoveries to come to light, had struck a deep chord in the young Chris Carter. “Basically, I just wanted to do something as scary as I remembered The Night Stalker being when I was in my teens,” he says. “I remembered being scared out of my wits by that show as a kid, and I realized that there just wasn’t anything scary now on television.” It seemed like a gap that Fox, which reveled in boundary-pushing content, might be thrilled to fill.

There were no aliens in The Night Stalker, nor in Carter’s earliest vision of The X-Files. Soon enough, though, a friend clued him into the underground world of ufology. Perusing the reams of poorly xeroxed newsletters, badly dubbed videocassettes, and obscure Usenet newsgroups that were the loosely organized cult’s primary means of communication, Carter realized that here was a whole ready-made milieu and mythology for his show, which could make it more than just a series of one-off encounters with the creepy and paranormal. For he wasn’t such a fan of The Night Stalker that he couldn’t see its limitations: “I think having a ‘monster of the week’ reduced the longevity of its storytelling capabilities.”

Soap operas had been indulging in long story arcs that spanned many episodes or even seasons for decades. Other genres of shows, however, had generally felt compelled to return the situation to a status quo at the end of every episode. Only recently had that begun to change. Still unsure how much they could get away with asking of their audience, most shows that were experimenting with longer story arcs were hedging their bets by mixing them up with more traditional, strictly episodic storytelling. The X-Files would be no exception. It would wind up producing “mythology” episodes about the alien menace only about one-quarter to one-third of the time, then rounding out the rest of its seasons with mostly self-contained “monster of the week” episodes.

The truth or fiction of the conspiracy theories from which Carter borrowed so liberally was not so much unknown as irrelevant to him. A child of the Watergate era for whom distrust of authority came naturally, he was drawn to write aliens into his show for the same reason that, one has to suspect, so many other people were writing newsletters about them: because they felt so simultaneously dangerous and alluring, in such marked contrast to most government scandals. Whatever else you could say about them, the Roswell crash, flying saucers, alien abductions, and the government coverups surrounding them all were a hell of a lot more fun than the Iran-Contra affair, the current White House’s scandal du jour.

As if that wasn’t grounds enough, Carter also had good reason to believe that the presence of aliens would make it easier to sell The X-Files to the suits at Fox. In the fall of 1991, just as he was beginning to put his pitch together, Fox debuted a program called Sightings, at first as a series of sporadically appearing specials. When these became unexpectedly popular, it was turned into a regularly scheduled weekly show in April of 1992, “investigating” all of the usual suspects: crop circles, cattle mutilations, alien-abduction accounts, and of course Roswell. Sightings was, in other words, the seed from which eventually sprang the alien-autopsy “documentary” — the start of a thriving cottage industry of cheaply made pseudo-documentaries dealing with aliens, conspiracies, and the paranormal that carefully avoided making claims to incontrovertible Truth but that always displayed a bias toward the believers’ rather than the skeptics’ side of the ledger. “Marketed correctly, these productions managed to be simultaneously authentic and phony, news and anti-news, without that feeling like any kind of contradiction,” writes television historian Emily Nussbaum. A scripted show dealing with the same subject matter, thought Chris Carter, might do even better.

Any such program could all too easily have become as kitschy and ephemeral as the likes of Sightings. It was the range of other influences which Carter brought to bear on The X-Files that would allow the show to transcend its humble origins, to become a shaper of the zeitgeist rather than a mere symptom of it. All were unusual to see on network television of the time: the Universal monster movies of the 1930s; film noir of the 1940s; the sci-fi B-movies of the 1950s; the cinéma vérité documentaries of the 1960s; the cynical post-Watergate conspiracy thrillers of the 1970s. To this list can be added blockbuster movies like Close Encounters of the Third Kind and The Silence of the Lambs (The X-Files liked its serial killers almost as much as it did aliens), and especially David Lynch’s heavily serialized, surrealistic television series Twin Peaks, which in its eight-episode first season in 1990 seemed to demonstrate that you could get away with asking a great deal indeed of your audience before it fell off the tightrope it had been walking and tumbled messily to earth during season two. Additionally, the television critic and historian Emily St. James makes a case for the influence of, of all things, the romantic “dramedy” series Moonlighting, which had a habit of upending all of its own formulas and indulging its experimental side for entire episodes at a time, taking “sidelong swerves into absurdism.” (I think St. James makes a reasonable case, although I do also think that these qualities are more in evidence a bit later in The X-Files’s run than they are at the beginning.)

As it evolved in its creator’s mind, The X-Files came to center on a tiny branch of the FBI whose assigned beat is “unusual” — read, apparently paranormal — cases. The two agents assigned to the branch were to be named Fox Mulder — the sort of name that could exist only in fiction, whose first part was an apparent homage to the network that would hopefully deign to permit him to exist — and Dana Scully. It was hardly unusual in network television at the time to throw an attractive man and woman together in a working relationship replete with will-they-or-won’t-they sexual tension — see the aforementioned Moonlighting — but Carter did defy gender stereotypes by making the male Mulder the credulous member of the pair and the female Scully the hard-eyed skeptic. Together, they would take on the sorts of cases that none of their colleagues would touch, which would often place them in conflict with shadowy forces inside their own government and their own agency who would prefer that any Truth that happened to be Out There remain hidden.

In December of 1992, Fox gave Carter a fine Christmas present indeed by ordering a pilot episode of the show. Now the pace increased exponentially.

And now Chris Carter got very, very lucky, by finding two stars for his show that were absolutely perfect. “We lucked out getting the chemistry we did,” he says. If anything, this is understating the case. For it really is difficult to overstate how important David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson were to The X-Files’s success. They were the special sauce that the show’s imitators would never be able to duplicate.

The 32-year-old David Duchovny, who earned the part of Fox Mulder, was an up-and-comer in Hollywood who was then best known for Red Shoe Diaries, a soft-core erotic series of the sort that flourished on late-night cable television in those days before the Internet put pornography on tap for everyone at the click of a mouse. He was almost scarily good-looking, the living embodiment of the phrase “tall, dark, and handsome,” but his secret weapon was his way with a desert-dry one-liner that undercut his Homecoming King face and figure. Like the character he played, Duchovny was smart as well as beautiful. He had been hard at work on a Yale PhD in English literature when he had stumbled into a casting call for a beer commercial at age 27 and emerged with a full-blown case of the acting bug.

The X-Files writing staff would have great fun with the contradictions in Duchovny’s alter ego in the years to come, making Mulder a guy who lived from paycheck to paycheck in a shabby little apartment, with no social life and no women in his orbit beyond his platonic partner Scully — unless you counted the actresses who starred in the pornography that, it would be slyly hinted more and more, he consumed voraciously when not trolling the Internet for tales of alien abductions. Many an X-Files guest star would shake his head that a guy who looked like that could live like this. Duchovny himself, whose choice of projects before and after The X-Files make it clear that he wasn’t afraid of indulging the id, kind of thought the same. “I’d like to see Mulder die one day,” he said once to a journalist. “Not soon, but one day. He should get laid, and then die.”

Gillian Anderson, who was cast as Dana Scully, was even less experienced than her counterpart, being just 24 years old at the time, newly arrived in Hollywood with a freshly minted acting degree from DePaul University and only a few theatrical credits to her name as a professional. A certain superficial resemblance to Jodie Foster, who had played a young FBI agent in The Silence of the Lambs, may very well have been a factor in her casting. Even if so, though, she quickly proved herself to be much more than just another pretty face. Granted, she was a bit stiff on occasion in the early episodes — the other cast and crew speak tactfully of a “learning curve” on the set for this actress who had hardly ever stood before a camera before — but she would find her groove as Scully soon enough. Gender dynamics being what they are, it would have been easy for the relentlessly logical and scientific Scully to come off as a shrewish spoilsport, but this is seldom the case. Anderson learned to make Scully her own, finding deep currents of warmth and humor beneath her scientific surface. A 2022 survey of American women with careers in STEM fields found that an extraordinary 63 percent of those of them who grew up during the heyday of The X-Files saw Dana Scully as a role model.

By a few seasons in, it would be obvious that these two characters who rarely touched one another and never called one another by their first names nevertheless loved one another in a far more believable way than the vast majority of couples who were doing the horizontal tango with regularity on television screens. They made a great team on and off the job. As the academic critic Erin Siodmak has written, “Scully kept it together while Mulder was overemotional, his judgment clouded by his obsessive search for the truth. She eye-rolled his quirks and most absurd theories, and she mocked his masculinity and bravado. Mulder respected Scully’s intellect, valued her work as a scientist, and offered the safety to be vulnerable without judgment.” I can’t emphasize enough how important this relationship was to The X-Files; it was the grace note the show needed to transcend its ripped-from-the-tabloids formula. I like to think it might have proved enlightening to some of the many young male fans of the show, by demonstrating how vibrant and exciting a relationship of equals between a smart man and a smart woman can actually be, whether they’re having sex or not. Be that as it may, Mulder and Scully are widely and deservedly numbered today among the most iconic onscreen couples in television history.

Needless to say, though, Fox had no idea what the series and its stars would become in these, their formative stages. The network’s big bet for the fall 1993 season was The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr., a big-budget, high-concept, tongue-in-cheek steampunk Western crafted in the spirit of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. The X-Files, by contrast, was envisioned as little more than a quickie spinoff from Sightings and its ilk. The budget Chris Carter was given to film his pilot reflected this.

“We came to Canada for the forests,” Carter would later say. In reality, that was only the smaller part of its appeal; the bigger draw was the money that could be saved. The pilot’s script involved, inevitably, an alien abduction, which it described as taking place in a forest in Oregon. Unable to find a spot that fit the bill in Southern California, and unable to afford a location shoot in Oregon, Carter hit upon Vancouver as the solution to his problem. The unbalanced exchange rate between the American and Canadian dollar would work hugely to the show’s advantage, even as the city government of Vancouver was offering a lot of other perks and incentives in a bid to attract productions just like this one. In this case, they worked better than those who initiated them could ever have dreamed; having come to Vancouver to shoot a pilot on the cheap, The X-Files would remain there for five seasons, 117 episodes, and one feature film. By the end of those five years, it would be difficult to find a place in the city where The X-Files hadn’t filmed at one time or another. “Around every corner I come upon an image from the show,” mused Chris Carter during a return visit in 2018. “Alleys we shot from every angle. Remarkably, from one high vantage, I can scan at least twenty locations where I directed David and Gillian in episodes and a movie.” To this day, the show’s hardcore fans continue to descend upon Vancouver to scope out the street where this chase scene took place or the building where that monster prowled.

The city became far more than just a way for the show to save money. The look of Vancouver — outside of its short but glorious summer, that is — became the look of The X-Files. “From September to late spring,” says Carter, “you can count on gray days in low light.” Even though the episodes were ostensibly set across the width and breadth of North America, as carefully explicated by a caption at the beginning of each one, they too were always marked by gray days and dark nights. An inordinate amount of rain followed Mulder and Scully around, regardless of where they went, enough so as to make you wonder if they were reincarnations of the “Rain God” Rob McKenna from Douglas Adams’s So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish. The murky visuals served to emphasize the show’s murky truths and moralities. (Ironically, the one type of landscape that was hardest for the show to simulate from wet and rainy British Columbia was the parched desert of the American Southwest, home to both Roswell and the second favorite site of UFO conspiracy buffs, the top-secret Air Force base known as Area 51, where the military supposedly test drives the technology recovered from extraterrestrials at Roswell and possibly elsewhere. In thus forcing the show to shy away somewhat from some of the most overtly obvious plot lines and locations suggested by its premise, this may have been no bad thing.)

The pilot episode which Chris Carter delivered to Fox in the spring of 1993 was compromised, as pilots usually are, by the need to do too much at once. It needed both to set up the conditions and characters of the weekly series that would hopefully follow and to demonstrate how a more typical episode would play out from week to week. On the whole, though, it did a serviceable job under the circumstances of bringing Mulder and Scully together at the FBI and sending them out on their very first case of hundreds to come. It even introduced the otherwise anonymous figure who became known as “Cancer Man” or the “Cigarette-Smoking Man” to fans, thanks to the bad habit in which he is constantly engaged; he would become the show’s most longstanding recurring villain, shadow-boxing against the protagonists’ efforts to uncover the truth about the American government’s contact with aliens and much else besides throughout its lengthy run. The pilot ended on what would become a very typical X-Files note, when all of the evidence Mulder and Scully had collected about the alien abduction at its heart literally went up in smoke, the victim of a mysterious fire back at their hotel. In time, this sort of thing would become intensely frustrating, a transparent dodge on the part of the writing staff to keep the wheels of the conspiracy plot lines spinning without ever actually moving them forward. This early on, though, it felt bracing in a television ecosystem where neatly wrapped-up happy endings were still the norm.

By way of further cementing the connection to tabloid programming like Sightings, the pilot episode of The X-Files opens with the claim that it is based on “actual documented accounts.” Strictly speaking, that means nothing whatsoever in terms of veracity; if I tell you a lie and you write it down, that is an “actual documented account.” Still, the show was probably wise not to show this card again after the first episode. I suspect that its existence here was largely at the behest of Fox — the network, that is, not the FBI agent.

Fox pronounced itself satisfied with the pilot. It agreed to fund a full season, albeit at a cut-rate budget of less than $1 million per episode.

So, the pilot was broadcast with little fanfare on September 10, 1993, followed by 23 more episodes over the next months. In a testament to Fox’s relatively low expectations, the show was relegated to Friday nights. Friday was, along with Saturday, one of the two most undesirable evenings of the week, a traditional dumping ground of shows whose potential was considered limited, since so many of the young adults who were most coveted by advertisers tended to be anywhere other than at home sitting in front of their televisions on those evenings. (This rule of television programming had held true for decades; students of Star Trek history will remember that it was NBC’s decision in 1968 to move that show to Friday nights that sealed its fate after just three seasons.)

The X-Files attracted only scattered, usually lukewarm reviews during its first year on the air. It was often described as a sort of low-rent copy of Twin Peaks, which was perhaps a partial truth but by no means a complete one. (To add grist to this mill, David Duchovny had actually had a small role in Twin Peaks, playing against his looks in a different way as a transgender law-enforcement agent.) The show put up mediocre ratings against weak competition in its inauspicious time slot.

In truth, it’s hard to argue that the critics were overlooking any deathless art in that first, comparatively little-watched season of The X-Files. Looking back on those early episodes from the perspective of today, I see a show that’s just good enough to make me wish it was a little bit better. Our current streaming era has, whatever its own infelicities, served to underline the weaknesses of the old broadcast-network formula all too plainly. Every X-Files episode has to wrap up in exactly 45 minutes, meaning that its scripts occasionally feel bloated and meandering, more often compressed, deprived of the space they need to breathe. Meanwhile the sheer quantity of episodes that the network demanded in a season meant that new ones had to be churned out at a tempo of one every eight to ten days. An uneven standard of quality is a virtual guarantee under such conditions. “When I was doing 24-episode [seasons],” says X-Files scriptwriter Glen Morgan, “we knew that three were going to suck, just because you couldn’t focus that much. People get annoyed with me for saying this, but, in all honesty, four [episodes] were great, most were okay, and some of them sucked. And that’s just how it goes!”

The first season was the phase when The X-Files was taking its core premise most literally. There’s little of the daring willingness to break its own rules that would come to mark the show in later years. In keeping with Chris Carter’s original mission statement, the show mostly just wanted to scare you in the beginning. And yet I must confess that I find its parade of aliens, monsters, and preternatural serial killers rather less terrifying than they want to be. It may be telling that my favorite episode of the season, the one called simply “Ice,” is largely a rewrite of John W. Campbell’s wonderfully creepy 1938 novella “Who Goes There?”

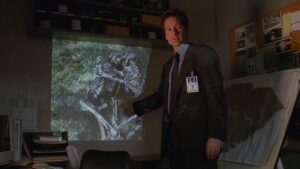

A stalemate in an Arctic research station in “Ice.” This early psychological thriller of an episode was unique for the way it turned Mulder and Scully against one another, something that would become almost unimaginable a little later in the show’s run.

To my mind, the first season stands out more for its visual aesthetics than for its writing. With so little money in the budget for shiny visual effects, the creators counted on the viewer’s imagination to fill in blanks that were hidden beneath an awful lot of rain and fog and smoke and darkness. The show used jittery photography to fine effect, a living embodiment of the nervous mood of the scripts; tight closeups in claustrophobic spaces were the norm. The X-Files may have been only dubiously good in the broad strokes at this stage, but it certainly had its own personality right from the start.

The show was saved from going down in history as a one-season wonder like its inspiration Kolchak: The Night Stalker by a happy coincidence involving a different, newer form of media than television. The very same month that the pilot episode was broadcast, Marc Andreessen of the National Center for Supercomputing Applications in Urbana, Illinois, released the first version of his NCSA Mosaic Web browser for personal computers running MacOS and Microsoft Windows. Mosaic was the most effortlessly usable browser to appear to that point, with a killer feature that would transform the look and feel of the nascent World Wide Web forever: it could display pictures on the screen alongside text. The arrival of Mosaic marked the moment when the Web went from being an esoteric tool for scientists and hackers to a revolutionary communications medium for everyone. In its wake, new websites sprang up in unprecedented numbers, as the first rumblings of what would become the dot-com explosion of the later 1990s began to make themselves heard. An inordinate number of these sites dealt with The X-Files, which was perfectly pitched to appeal to the legions of brainy, plugged-in, usually male university students who were Mosaic’s most prominent early adopters. There was a time when it seemed that every tenth site on the Web was an X-Files site.

The X-Files became the first example of a new phenomenon in traditional media, the first television show whose popularity was almost entirely a credit to the new medium of the Internet. On their personal websites and in the freewheeling discussion forums of Usenet, the self-proclaimed “X-Philes” declared their love, stated their opinions, and argued endlessly over matters large and small. The monster-of-the-week episodes were all well and good, but it was the mythology episodes that really got them revved up. These were dissected on an almost frame-by-frame level of detail — far more detail, if we’re being honest, than they deserved, given the extent to which the writing staff was winging it as they went along. Some of the hardcore fans were disposed to believe in actual government conspiracies, while some were not. But all of them relished the ones seen on the show, wanted to believe as badly as Mulder did that there was a detailed master plan to the mythology locked up in some office at Fox. In truth, of course, no such thing existed then nor ever would.

The obsessive tendencies of the most devoted fans could be almost as disconcerting as they were gratifying to the people who made the show. David Duchovny remembers stumbling into a heated discussion of why the petite Scully is never shown adjusting the car seat after taking over driving duties from the tall and lanky Mulder. “That was probably the last time I ever looked at the Internet, because that kind of frightened me,” he says, only half in jest.

Buzz over The X-Files gradually spilled over to other groups whose Venn diagrams overlapped with that of the early Web denizens. One of those with the biggest overlap, and thus another of the groups where the show made its presence known first, happens to be a special interest of this website: computer-game players and developers. Before the show’s first season had even concluded, the first game to bear the stamp of The X-Files had already appeared on American store shelves.

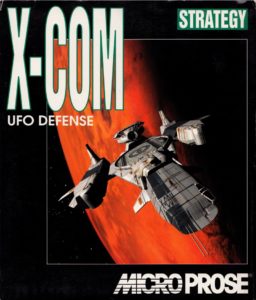

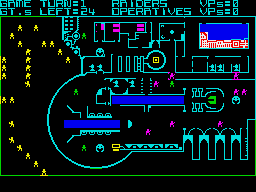

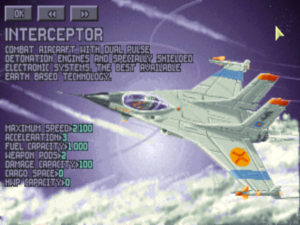

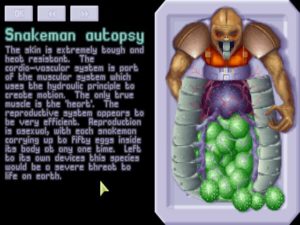

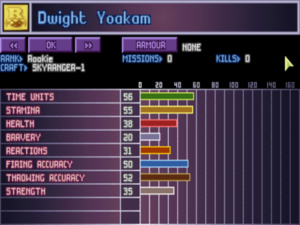

The Britain-based brothers Julian and Nick Gollop and their tiny studio Mythos Games had started working on a strategy game they called UFO: Enemy Unknown, about a full-blown alien invasion of Earth, a good year and a half before the show made its debut. But by virtue of drawing from many of the same underground ufological sources as The X-Files writing staff, they ended up with similar-looking extraterrestrials and an almost uncannily similar brooding, ominous atmosphere — this despite the fact that the Gollops had never even seen the show, which wouldn’t air in their homeland for the first time until six months after their game was released. Nonetheless, the Gollops’ publisher MicroProse played the similarities up for all they were worth in the United States, going so far as to rename the game there to X-COM; suffice to say that the shared “X-” prefix was not a random happenstance.

Hints of The X-Files would continue to show themselves in many games for the rest of the decade, from the Tex Murphy series to Fallout. And small wonder: Friday-evening X-Files viewing parties became a bonding ritual at countless games studios, the perfect way to celebrate the conclusion of another working week. The same ritual was enacted by millions of ordinary gamers.

The early fan enthusiasm, combined with a rock-bottom budget and the lack of anything else to put into its Friday-night time slot, were enough to get The X-Files renewed by Fox for a second season that began in September of 1994. (Poor Brisco County, on the other hand, had seen its ratings collapse after a strong start and was cancelled after its first season.) Yet the moment when it became clear that The X-Files was really breaking through didn’t arrive until that December, when the show was unexpectedly nominated for a Golden Globe Award in the category of Best Television Drama. And then, even more incredibly, it won the award the following month, beating out such prestigious critics’ darlings as ER and NYPD Blue. To this day, nobody can quite explain how this happened. At the time, nobody was more shocked than the people who made The X-Files. “When we won, you could hear a pin drop,” says the show’s co-producer Paul Rabwin of the reaction in the auditorium. “It was like the longest shot in the world coming in, and everyone was dumbfounded.”

Suddenly The X-Files had a serious buzz about it. By the end of season two, it was regularly winning its time slot. While the numbers it put up still weren’t huge in the abstract, they were an advertiser’s wet dream in terms of demographics. The prototypical X-Files viewer was described as “male, 25 to 34 years old, college educated, residing in the northeastern United States, a moderate television viewer but also a Star Trek fan, and an Internet user.” Millions of people who resembled at least some parts of this description were willing to plan their Friday evenings around catching the latest episode of the show. The pump had been well and truly primed for the alien-autopsy special that aired on Fox that August.

Whatever was fueling the show’s growing popularity, it certainly wasn’t a case of full-scale reinvention. Going into the second season, Chris Carter had made it clear that his core vision was unchanged. “Ultimately,” he said, “my goal [is] the same that it’s always been: to create 22 to 24 really scary shows. I just want to scare the hell out of the audience. That’s all.”

Unsurprisingly, then, the second season of The X-Files isn’t hugely different from the first in style and spirit. The Cancer Man is still smoking in the shadows in the mythology episodes, and serial killers are still the monsters of the week as often as not. That said, there are some signs that the show is changing. The episode “Die Hand Die Verletzt” is a slightly tongue-in-cheek story of a cabal of Satanists who double as a local school board. It draws more from the farcical, partially Dungeons & Dragons-fueled Satanic panics of the 1980s than it does from more respectable Satanic horrors like Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist. Fox had once been all over that stuff, much as it was all over the UFO stuff now. More and more as time went on, The X-Files would be sending up the tackier tendencies of its parent network.

But the episode that really threw open a window to let some fresh air into the show’s hermetically sealed world appeared two months later. The script for “Humbug” was the first to be credited solely to Darin Morgan, who would go on to become one of The X-Files’s standout writers. Its setting, an encampment of carnival sideshow performers, was plainly inspired by the unnerving 1932 B-movie Freaks. In this context, however, it was used in the service of something perilously close to full-on comedy. This was a first for the show, one which had prompted much debate and soul-searching among the production staff and at the network before the episode was green-lit. The circus performers spend most of their time taking the piss out of Mulder, this mental Hephaestus in the body of an Adonis. And when the script isn’t making fun of him through them, it’s making fun of some of the core premises of the show itself. By no means were all of the fans pleased by this development; it seemed to some of them a slippery slope from mocking the show that they adored to mocking them. Even the fact that the episode aired the night before April Fool’s Day, thus indicating that a comedy installment might become no more than an annual indulgence at worst, wasn’t enough to mollify all of the viewers who liked their X-Files dark and po-faced.

“Well, why should I take offense? Just because it’s human nature to make assumptions about people purely on the basis of their physical appearances? Why, I’ve done the same thing to you, for example. I’ve taken in your all-American features, your dour demeanor, your unimaginative necktie design, and concluded that you work for the government… an FBI agent. But you see the tragedy? I have unconsciously reduced you to a stereotype, instead of regarding you as a specific, unique individual.”

“But I am an FBI agent…”

For my part, though, I say it was about time. After all, The X-Files is a pretty ridiculous show on the face of it, riven from top to bottom with cognitive dissonance. Mulder and Scully are simultaneously the two busiest and the two most incompetent agents in the history of the FBI, who have apparently never heard that most important piece of advice for anyone trapped in a horror movie or in a law-enforcement training course: Don’t split up! They’re constantly rushing alone into danger without bothering to tell each other what they’re doing, much less telling any of their other colleagues, and constantly getting themselves almost killed, being saved only by the plot armor provided by their place at the top of the credits list.

Unanswerable questions abound. Why does a government whose conspiratorial tendrils reach into every conceivable aspect of life not just kill these two rogue agents in its midst? Why does Scully insist anew at the beginning of every single episode that, no, this latest case surely doesn’t involve anything supernatural, when by the end of the episode it almost always does? Isn’t her perverse resistance to extraordinary evidence in some way the opposite of the scientific method?

By slyly cluing us in to the fact that the show’s own creators were aware of all of this — that they were actually much smarter than the likes of Sightings — “Humbug” gave us permission not to take the show so seriously. We know it’s silly and you know it’s silly, it seemed to say, so feel free to laugh if you want to. Or, if you like, feel free to take the show seriously but still not quite literally. Vintage television is sometimes described as a character- rather than a plot-driven format. We watch mainly in order to hang out with characters that we know and like; what they actually get up to there on the screen is just the excuse for giving them a show. Happily, and despite the novel ambitions of the mythology plot lines, The X-Files had two leads strong enough to make the show work on this level. Mind you, this would not keep some fans from trying to slot every little anecdote into some master canon of an X-Files universe — and more power to anyone who enjoys that sort of thing. But it was and is a nice message for the less literal-minded among us to hear. As the first episode willing to unabashedly embrace the “meta,” “Humbug” might just be the most important — not the best, but the most important — episode of The X-Files ever made.

By the third season, more X-Files episodes — especially the ones written by Darin Morgan — were abandoning the usual formulas to begin mining richer veins of myth and magical realism. “Clyde Bruckman’s Final Repose,” for example, gives us a man who has been cursed to foresee the whens and hows of the deaths that await every single one of us someday. One of the most touching moments in the show’s history comes when Scully asks him how she will die. “You don’t,” replies veteran character actor Peter Boyle in a voice touched with mercy, with an expression on his face that tells us all too clearly that he’s lying. Such are the lies that we all tell ourselves and one another in order to get through this thing called life.

And then there’s “Jose Chung’s From Outer Space,” a suitably odd name for an incredibly odd episode. Here The X-Files goes full-on postmodern avant-garde for the first time, wrapping truth and fiction and the liminal spaces in between into a hopeless tangle that’s shot through with allusions to everything from Star Wars to Close Encounters to Twin Peaks. Jose Chung himself is a riff on Truman Capote, writing a version of In Cold Blood involving aliens. His presence, along with a cameo by Alex Trebek, the host of the television game show Jeopardy!, is an elaborate callback to David Duchovny’s turn on Celebrity Jeopardy!, which he lost to author Stephen King in the final round when he couldn’t remember the name of Capote’s novel Breakfast at Tiffany’s. And so it goes, and so it goes, around and around in a fashion guaranteed to delight any post-doc in postmodern literary theory.[1]The first full-length academic book deconstructing The X-Files appeared already in 1996, while the third season was still airing. The contents are sometimes insightful, sometimes hilariously banal in that special way that only academic writing can be. A sample of the latter type:

“These episodes not only establish a comparison between Mulder and various tragic truth seekers but also reveal the erotics of the search through repeated imagery of penetration. The extraterrestrial energy-being of ‘Space’ painfully possesses Colonel Belt, the silicon-based parasite erupts from the throats of its cave-explorer victims like a phallus, the subatomic particles ‘come into’ Banton’s body. The ‘penetrating answer’ turns upon, penetrates, and destroys its finder. The logic of the show repeatedly represents the object of desire, the much-cited truth, as itself a phallic power with a will of its own.”

You heard it here first, folks: the Truth that is Out There is really a giant penis just waiting to skewer you like a pig on a spit.

In this episode, The X-Files comments for a second time in the course of a single season on the real-world alien-autopsy sensation for which it itself had laid the groundwork. The moment when Scully conducts her own autopsy on an alien, only to snag her scalpel on a zipper — it turns out that it’s just a dead guy in an alien suit — is as hilarious as it is subversive. Ditto the way the show, just one year removed from its first tentative steps in this direction in “Humbug,” now dares to directly and unabashedly mock a portion of its most hardcore audience, personified as a young man living in his parents’ basement who wants desperately to be carried away by aliens so that his dad will stop hounding him to get a job. “Roswell! Roswell!” he shouts apropos of nothing when all other words and logic have failed him.

“There are those who care not about extraterrestrials, searching for meaning in other human beings,” Jose Chung tells us at the end. “Rare or lucky are those who find it.” It’s strongly implied that they are the most enlightened ones, regardless of their ultimate success rate — a strange message for a show invented to exploit interest in UFOs to convey, but by no means an unwise or unwelcome one.

At the beginning of the fourth season, Fox finally saw fit to move The X-Files out of the Friday graveyard slot and over to Sunday evenings. The twelfth episode of that season aired just after the Super Bowl on January 26, 1997, becoming thereby the most-watched single installment of the show ever, seen by almost 30 million American households. From its humble roots, The X-Files had grown up to become a show that absolutely everybody at least knew of. “You cannot get an issue of TV Guide or Entertainment Weekly or People without someone referring to the show,” marveled Paul Rabwin. “There have been political cartoons, references in the funnies, and newspaper headlines. It’s no longer something that needs explanation.”

Yet the show definitely wasn’t dumbing itself down to please the masses. Foucault’s Pendulum has nothing on the conspiracy theorist’s magic brownie that is the fourth season’s “Musings of a Cigarette-Smoking Man,” in which we learn that Cancer Man not only personally carried out the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King but has been fixing the Grammy Awards and the Super Bowl all these years as well. (He has a special dislike for the Buffalo Bills.) We even see him watching the pilot of The X-Files approvingly, implying that the whole show we’ve been viewing is yet another piece of government misinformation. The mind boggles…

It turns out that Cancer Man is a frustrated author who has a vendetta against the world because he can’t get a story published.

It’s clever, yes, but is it anything more than that? There’s only so far you can take this sort of thing before it becomes masturbatory — empty tricksterism for its own sake, without much to say to us beyond well-worn grad-school clichés about the “instability of truth” and the “illusion of the objective” and all the rest of that tired lot.

Enter one Vince Gilligan, who had started writing for The X-Files already in the second season but didn’t really begin to come into his own until the fourth, when he claimed the title of the show’s most consistently interesting scriptwriter from Darin Morgan. As if to highlight this passing of the guard, the latter stepped in front of the camera to star in Gilligan’s “Small Potatoes,” playing a schlubby loser named Eddie who has the power to take on the appearance of any man he wishes to be. Predictably enough, he uses this power to seduce women left and right. Inevitably, he winds up becoming Mulder, and is closing in for the kiss with Scully which we’ve been waiting the better part of four seasons to see when the real Mulder bursts in on the two. Like so many of Gilligan’s scripts that are still to come, it’s funny and thought-provoking but also warm and sweet and a little melancholy, operating almost on the level of parable, a million miles removed from the gritty horror which the show was always trying to project in its earliest days. I think I see a kindred soul in Vince Gilligan: someone who is less fascinated by the plot machinery of the show’s myriad conspiracies than he is by this man who’s decided to devote his life to chasing chimeras and by this woman who, it’s pretty clear by now, loves him deeply and is loved by him in return. “I was born a loser, but you’re one by choice,” says the once-more schlubby Eddie to Mulder at the end. “You should get out and live more.”

More extreme incarnations of people like me and perhaps Gilligan were becoming prominent in X-Files fandom by now. They were called the “shippers,” as in “relationshippers.” The most obsessive analyzed every stray glance that Mulder and Scully cast at one another every bit as exhaustively as another type of fan pored over fleeting shots of aliens and every randomly dropped aside by Cancer Man. Some shippers preferred to keep to the terrain of speculation, while others wrote exactly how it would go down once Scully finally agreed to give Mulder’s sadly underused but doubtless impressive manly member a good solid shakedown trial. The majority of the shippers were women, who were flocking to the show in increasing numbers now.

Indeed, by the end of the fourth season, The X-Files was at its zenith of popularity and cultural influence. It was the biggest show on Fox by a wide margin and the fourth most popular drama on all of network television. (Within that category, it trailed only ER, Touched by an Angel, and NYPD Blue.) Its tag lines — “The Truth Is Out There”; “I Want To Believe” — were being repeated everywhere, sometimes in earnest and sometimes in jest, much as on the show itself. Chris Carter’s Millennium, a semi-spinoff from The X-Files about an FBI agent who could read the minds of criminals, had just finished its own first season to positive reviews and solid ratings. Never a man lacking in ambition, Carter was making plans to conquer a whole new realm by shooting an X-Files feature film between the fifth and sixth seasons.

And oh, yes… there was to be an X-Files game as well — a game, that is, that wasn’t just influenced by the show but actually sported its name on the box.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books “Deny All Knowledge”: Reading the X-Files, edited by David Lavery, Angela Hague, and Marla Cartwright; Conspiracy Culture: From Kennedy to The X-Files by Peter Knight; Monsters of the Week: The Complete Critical Companion to The X-Files by Zack Handlen & Emily St. James; X-Files Confidential: The Unauthorized X-Philes Compendium by Ed Edwards; Cue the Sun!: The Invention of Reality TV by Emily Nussbaum; The Legacy of The X-Files, edited by James Fenwick and Diane A. Rogers; Opening the X-Files: A Critical History of the Original Series by Darren Mooney; and The Nineties: A Book by Chuck Klosterman.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The first full-length academic book deconstructing The X-Files appeared already in 1996, while the third season was still airing. The contents are sometimes insightful, sometimes hilariously banal in that special way that only academic writing can be. A sample of the latter type:

“These episodes not only establish a comparison between Mulder and various tragic truth seekers but also reveal the erotics of the search through repeated imagery of penetration. The extraterrestrial energy-being of ‘Space’ painfully possesses Colonel Belt, the silicon-based parasite erupts from the throats of its cave-explorer victims like a phallus, the subatomic particles ‘come into’ Banton’s body. The ‘penetrating answer’ turns upon, penetrates, and destroys its finder. The logic of the show repeatedly represents the object of desire, the much-cited truth, as itself a phallic power with a will of its own.” You heard it here first, folks: the Truth that is Out There is really a giant penis just waiting to skewer you like a pig on a spit. |

|---|