Legend Entertainment fought something of a rear-guard action through the first half of the 1990s. In an industry that had embraced the movies as its aesthetic example, their works remained throwbacks to older ideas about interactive books: “We had the editorial sensibilities of a book publisher rather than a movie company,” says Legend co-founder Mike Verdu. Their games were wordy, and even after the migration to CD-ROM the player was expected to read many of those words for herself rather than have them read aloud to her; they sported illustrations that were carefully composed and lovely to look at, but that were also static in a motion-obsessed gaming milieu, and thus were better suited to stand up well a quarter-century later than they were to wow the masses in their own day. Enough players were intrigued by Legend’s low-key, literary approach to buy 30,000 to 60,000 copies of each new game, but those consistent numbers translated to a steady erosion of Legend’s market share in a fast-expanding industry; by mid-decade, many new games were selling over 100,000 copies each year, and blockbuster million-sellers were appearing at a clip of three or four per annum. Verdu and his partner Bob Bates felt serious pressure to up Legend’s sales and keep pace with their peers.

But, you might say, surely market share isn’t everything. Why couldn’t Legend be content within the niche they had built for themselves? The answer comes down not to hubris but to the harsh realities of game distribution in the 1990s. Games of the type that Legend made still needed to exist as physical products at that time. (Although there was a thriving shareware scene taking advantage of digital distribution, the dial-up online access that was the universal norm could support only small, multimedia-light titles — not the assets-heavy, CD-filling monstrosities of Legend.) Physical products required physical warehousing, physical distribution, and, most critically of all, precious physical shelf space inside brick-and-mortar stores. Here was the real rub. A niche product like a Legend adventure game was a hard sell to a retail purchasing manager who could instead fill the space it would occupy with the likes of a 7th Guest, Myst, DOOM, or Wing Commander III. In short, Legend’s modest product line was in danger of drowning in the flood of flashier, better-advertised games. All of the quality in the world would avail them nothing if they could no longer get their games into the hands of their fans.

So, after the book publisher Random House was inspired by Legend’s literary bona fides to invest $2.5 million in the company in the summer of 1994, Verdu and Bates decided to use a substantial chunk of that money to make a play for the big time. They would make a game set in a node-based, 3D-modelled environment much like that of Myst, and hire a name actor beloved by science-fiction fandom to star in filmed “full-motion-video” sequences, just like Wing Commander III had done. But, because they were Legend, they would invest all of this trend-chasing with meticulous attention to detail in terms of world-building, plot, and puzzle design, and would respect their player’s intelligence and time in a way that too few of their superficially similar peers were doing. What else could Legend do? They were just made that way.

Mike Verdu wrote and designed the game in question, which went by the name of Mission Critical, and shepherded it through every phase of its development. I recently talked with him at some length about the project, and I’ve elected to present this article to a large extent as his own oral history of it. This seemed to me the most appropriate approach, given that he’s more than articulate enough in his own right, and given how his recollections provide such a fascinating picture of how the nuts and bolts of a game came together during the much-ballyhooed era of Siliwood — that semi-mythical convergence of Silicon Valley and Hollywood.

For me, full-motion video wasn’t so much the imperative. It was creating the next generation of adventure gaming using immersive environments. With a text adventure, the world is really in your head; it’s created in your mind by the words that we put in front of you. We added illustrations to the picture that the words formed in your mind, but I always dreamed of actually putting you in the world, having it become a fully immersive experience.

So, the primary driver for me was immersiveness. Full-motion video was a cool thing that you got because you had CD-ROM as a storage medium. I had long dreamed of creating a world that you could actually inhabit. The world would feel alive. We wouldn’t have to tell you what it was like, we could show you. That’s where CD-ROM met the state of the art in 3D. We could use AutoCAD and those sorts of tools to deliver a world at a very high level of fidelity through pre-rendered segments. The creative spirit that guided me was bringing a fully realized 3D world to life, and then telling a story in it. That was just delicious. I loved that challenge, couldn’t wait to take it on.

Mission Critical stands today as a landmark in Legend’s history in more ways than one. Legend’s first and, as it would transpire, only serious flirtation with the full-motion-video trend, it would also prove the very last Legend game that was entirely original to them, not being based on any preexisting literary or gaming license. Which isn’t to say that it isn’t derivative in another way: it’s a military space opera of a stripe that will be familiar to readers of David Weber, with some Big Ideas almost worthy of a Vernor Vinge hidden behind its façade of outer-space adventure aboard the Lexington, an interstellar ship of the line in the year 2134.

The Lexington is a combatant in an Earthly world war which has spilled well beyond the boundaries of our solar system. The backstory begins with the evolution of the United Nations into a tyrannical “world government” by the late 21st century. (The political connotations of this setup in the context of our conspiracy-theory-plagued contemporary world are perhaps unfortunate…) Out of fear of a forthcoming technological Singularity, the UN orders a halt to all forms of research and development, opting for a world that is frozen in amber over one where computer brains replace human ones. Feeling that “the cure is worse than the disease,” the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan, and Singapore, along with all of the planet’s nascent space colonies, rebel, and are promptly targeted for “brutal suppression” by the UN. The Lexington, naturally, fights on the side of the freedom-loving pro-techologists, who call themselves the Alliance of Free States.

I had a personal passion for science fiction — not a surprise, given my Gateway games — and had been doing a lot of reading about where technology was at and the Singularity and the early ponderings of what would happen when artificial intelligence surpassed human intelligence. What would that mean? Would it result in an alien form of life, or would it be anthropomorphic in some way because its creators would endow it with human qualities? What would it mean for humanity to reckon with the emergence of artificial intelligence? Would it tear us apart or bring us together? That was the beating heart of the story I wanted to tell.

Then I combined it with a love of ships and the Navy and sailing. I’ve been fascinated by ships forever. I used to draw them and collect models of them and was always thrilled to go down to a port and see the ships there.

I tried to make the science behind the ship’s systems as real as possible. I did a lot of thinking about what actual combat in space might be like. It was certainly not going to be managed by humans; it would be managed by drones. The ships are really just drone carriers. They send the drones out to resolve the battle, and the humans, once the battle starts, are just sitting there going, “Oh, God, I hope this goes our way!”

All of these ingredients came together in a creative stew. But then, there were lots of constraints imposed by the medium. You couldn’t put other characters in there. It had to be a sterile environment, like you saw in The 7th Guest and some of the other earlier products in this space. My answer was to put the other characters in the full-motion-video sequences. Your emotional connections would be made in the opening sequence, and then other video snippets that you would bump into. But it was still pretty thin gruel. A lot of games from this era feel very empty because you couldn’t put other characters in these kinds of environments.

So, that was a major constraint. I was going to have this really cool ship filled with drones that could fight battles, but there couldn’t be anybody else on it. So, there had to be a fictional reason why you were by yourself. But that also is very heroic because, if it’s just you, and you turn the tide of an important event in history, that’s a nice character arc. And there is some artistic resonance to one human alone on a ship light years from anyone else. What that feels like, the lack of connection, the sense that it’s all riding on you.

So, yeah, the story had to be thought-through in a way we had not had to do with previous Legend games, just because, like in a movie, every scene had to be designed, scripted, and then fed to the people who were actually doing all of the rendering. We had very little ability to mess with the story after it had been shaped. That constraint was unfamiliar to me because we had been able to tweak previous Legend games all the way down to the end. It was just writing code — change responses, change puzzles, write some new text, maybe commission a couple of new pieces of 2D art. This time, everything had to be down well in advance, then it was locked down. So, I’d never done so much up-front planning on a game before.

It was a lot of work. I worked harder on that game than I’ve ever worked on anything. The team slept under their desks, worked through the night and into the next day.

The player’s situation is set up in a bravura ten-minute movie that opens the game, filling most of the first of its three CDs. The Lexington is on a beyond-top-secret mission to a planet called Persephone, escorting a science vessel known as the Jericho. But it seems that the Alliance’s security has failed: the ships are met there by a much larger UN cruiser. The Lexington‘s drones are easily defeated, leaving it and the Jericho helpless. At this juncture, the Lexington‘s Captain Dayna, who is played by none other than Michael Dorn — the Klingon Worf from Star Trek: The Next Generation — concocts a clever if suicidal plan for preventing the logs of the Jericho, which give the full details of its mission, from falling into enemy hands. He surrenders to his opposite number, and makes arrangements for the crews of both of the vessels in his task force to fly over to the UN cruiser in shuttles. But then he does two things the UN captain does not expect. First, he plants a nuclear bomb in one of the shuttles that will blow up and destroy the UN cruiser and everyone aboard, along with all of the other shuttles and everyone aboard them, as soon as it enters the cruiser’s docking bay. And then he leaves one crew member behind on the Lexington — one person not being worth the UN captain’s bother when he scans the ship to make sure Dayna is abiding by their agreement — to hopefully find a way to complete the original mission alone. That crew member, of course, is you the player.

Michael Dorn and the other actors received top billing in the credits of a game that absorbed at most a few days of their time, while the names of the people who worked for months on end and slept under their desks came in smaller lettering much later in the credits sequence. Such was the strange reality of Siliwood — which, come to think of it, is not that different from standard Hollywood practice.

There was a trend in gaming at the time to lean into celebrities; it was part of this convergence with Hollywood. I knew that I was telling an entirely original story, that we were making one of the biggest bets in the company’s history. I had a sense that we needed a hook that would give a customer reading about the game or looking at it on a shelf some sense of familiarity — a brand that they could latch onto. I knew the market was very crowded with games that looked somewhat like this. So, I thought to cast an actor who would have a resonance with the story we were telling. People would think about the actor in that context, and say, “Oh, I get what kind of story this is going to be.” I was trying to come up with a shorthand way of communicating what it was all about.

We knew absolutely nothing about film making, but I did work with an artist named Kathleen Bober, who had all sorts of connections in the theater scene in Baltimore and Washington, D.C., and with a number of video-production companies, including one called Flight Three, which did commercials and other television productions. She and I did a lot of the initial explorations. How do you hire an actor? How does it work? How do you actually do a video shoot? Who can we hire to stage the production? How much does it all cost?

I knew something about dealing with agents because we had dealt with literary agents. So, reaching out to see if we could find an actor who felt right for the role, who had a brand compatible with the story we wanted to tell, was weirdly the least challenging part of it all. The much more challenging part was finding a director and a production facility, learning how to shoot in green screen and composite in environments. Kathleen put together a team for that. The director’s name was Peter Mullett. We brought him on, then worked with Flight Three to create a plan and a budget and a script. I wrote the script; all the painful dialog is my fault. The filming was done in a suburb of Baltimore. We only flew Michael Dorn out for a day or two for the opening movie. It really was that short. Then all of the other little segments took another day or two. The prep for it all and then the post-production took all the time; that was months.

My entire career at that point was just learning, drinking in how to do all kinds of new stuff. I just saw this as one more thing to learn.

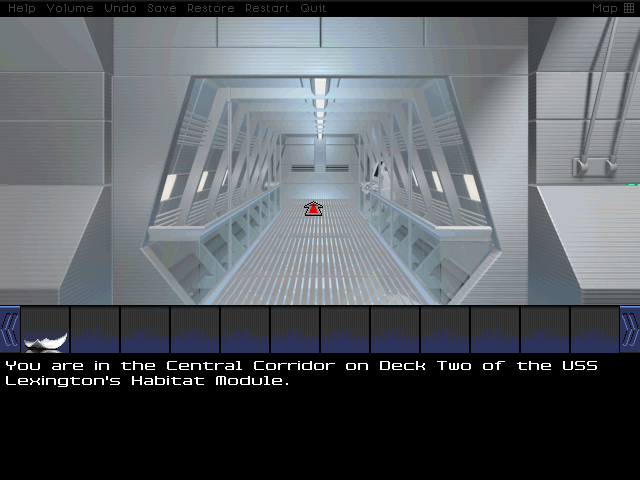

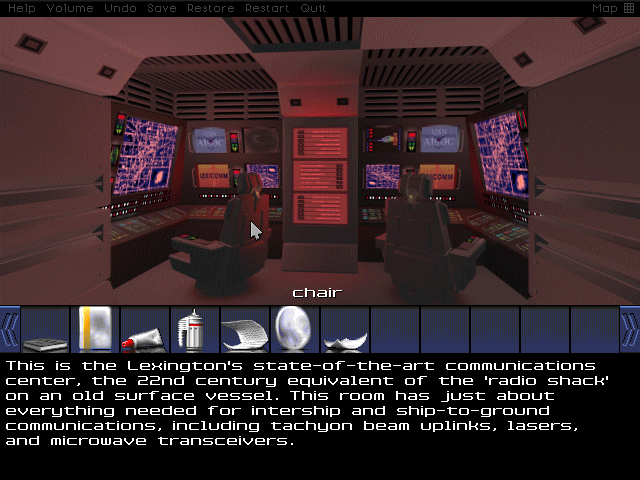

When the opening movie finishes and the game proper begins, you find yourself standing in a corridor of the wounded Lexington, observing the world around you from a first-person view. The latter in itself isn’t unusual for Legend; all of their games prior to Mission Critical use the same view. Yet a difference in kind quickly becomes apparent. Whereas the older Legend games, in keeping with the company’s roots in text adventures, use a room-based approach to navigation, Mission Critical‘s is based on nodes within a larger contiguous environment. Thus you can now spin around to view your surroundings in any of four directions. And instead of using pixel art, the views have been pre-rendered in a 3D modeler. Legend, in other words, has seemingly gone full Myst.

You encounter a series of intricate mechanical puzzles as you begin to explore this environment. The first third of the game comes to revolve around repairing the Lexington enough to make it reasonably space-worthy and even combat-worthy again. In the course of doing so, you learn about the lives and personalities of your late fellow crew members by rummaging through their personal effects, and also identify the traitor who betrayed your mission to the UN. Again, the Myst comparisons are unavoidable; the Miller brothers’ game uses much the same kind of environmental storytelling.

There were a bunch of Myst-style games, including some that have faded from memory. CD-ROM enabled a certain kind of production, and then there were a whole bunch of games that seemed similar. It was like this brief emergence of a genre. Then the state of the art moved on, and people figured out how to tell more character-based stories.

I wanted to put real puzzles in one of these games. My sense with these games was that the player interactions were really basic. Legend was known for making great puzzles; I wanted to put great puzzles in one of these games. I wanted to make a true Legend adventure game that just happened to be within this amazing immersive environment. I would like to think that what distinguishes Mission Critical from some of those other products — and may actually have limited its commercial potential, frankly — was the depth and sophistication of the puzzles. The puzzles in this game are serious, hardcore adventure-game puzzles. It was my attempt to make this very rich experience, and not have it be just manipulation of objects. That was my way of differentiating Mission Critical from Myst and other products of that type.

I might quibble with some of Mike’s characterizations of Myst; whatever the design sins of its many imitators, Myst‘s own worlds are scrupulously consistent within the game’s fantastic premise, and its puzzles are quite rigorously logical. Still, there’s no question that Mission Critical boasts a much richer, deeper environment, if perhaps a more prosaic and less evocative one, and that its custom engine admits of forms of interactivity that the simple off-the-shelf software tools employed by the Miller brothers and many of those who followed them couldn’t hope to match. Myst and many other games of its lineage don’t even have player inventories; this may lend them a degree of minimalist elegance in aesthetic terms, but is profoundly limiting in terms of gameplay.

Mike Verdu was obviously aiming for something else. The Lexington is not just vividly but realistically realized once one accepts the black-box premise of faster-than-light travel. Its systems work in a consistent, thought-through way, with nary a gratuitous slider puzzle nor instance of awkward self-referential humor to be found. Anyone annoyed by the artificiality of most adventure-game puzzles needs to play this game. One might go so far as to say that the Lexington itself is Mission Critical‘s most impressive single achievement. The game’s commitment to the lived reality of the ship remains complete from first to last.

I did a stint in defense contracting where I worked on Navy projects, including a lot of submarine-related projects. If you see any verisimilitude — a feeling that the world of the Lexington has some degree of reality to it — that’s me drawing on experiences of visiting Navy yards and tramping around submarines and reading lots and lots of documents. The Lexington is really a submarine in space. I drew on my experience to make it feel like a lived-in ship.

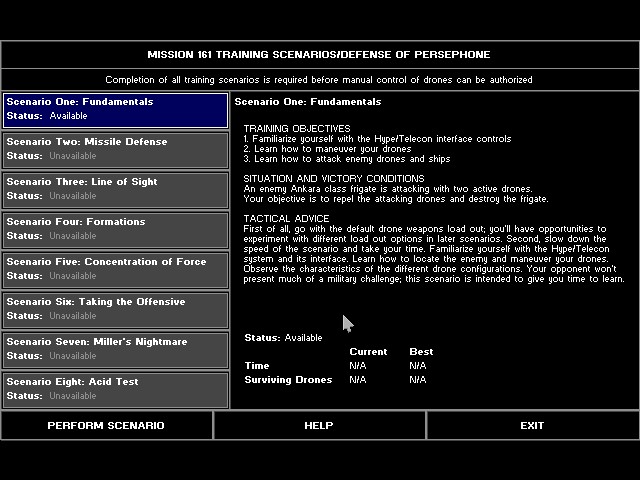

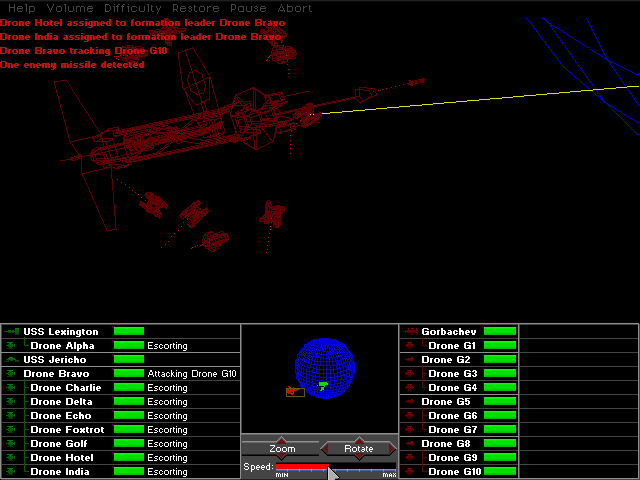

Your efforts to repair the Lexington are lent an added sense of urgency when you learn that another UN force is on its way to Persephone to investigate the fate of the first one. Dealing with it comes to occupy the middle third of the game. Space combat is implemented in the form of a surprisingly well-realized real-time strategy game that’s embedded within the adventure game. While the graphics don’t rival the likes of its standalone contemporary Warcraft II, much less a modern release in the genre, I find that it defies a long tradition of dubious adventure mini-games by being genuinely engaging. As usual, Legend’s design instincts are good; instead of plunging you into a fight to the death within a mini-game interface you’ve never seen before, they introduce it through a series of training simulations that get you up to speed within the framework of the story.

What you’re seeing there is my love of strategy gaming shining through. It’s probably no surprise that I went on to make a bunch of real-time-strategy games after my adventure games because my two great loves are storytelling and strategy. I grew up playing Avalon Hill board games; my dad taught me to play Tactics II and Afrika Korps and Squad Leader. Then I played a lot of the first generation of computer strategy games. I dearly, desperately wanted to make my own strategy game at some point. This game seemed to offer the opportunity to put in a little taste of strategy that would feel very natural. So, why not? Bob Bates was sort of horrified that I wanted to put an entirely different genre of experience into an adventure game. The compromise we reached was a button you could hit to just have it resolved. You never really had to do the strategy game.

Mark Poesch, the engineer who did most of the coding on Mission Critical, spent a lot of time trying to figure out how to build it out. We wanted to bring to life this notion that the battles were fought with drones, and also that fighting in 3D is very different from fighting in 2D. Almost all outer-space strategy games take place on a plane. Those games like Homeworld that tried to introduce a third dimension found that it’s very hard to convey the sense of fighting in 3D space.

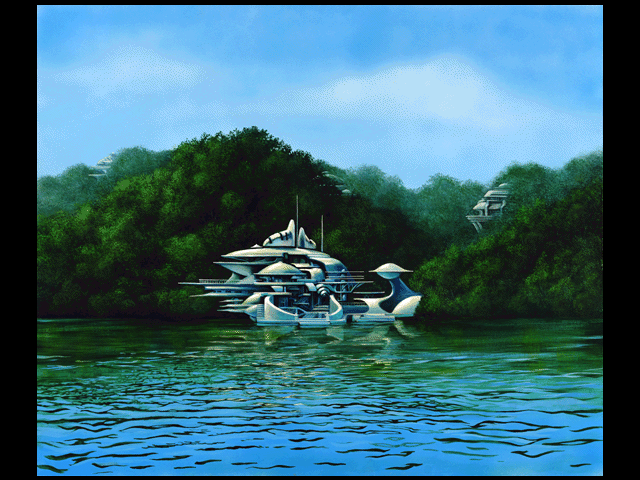

In the last third of the game, we shift gears dramatically once again. Now you finally make your way down to the surface of the planet Persephone to find out what the science team aboard the Jericho was so interested in. It’s here that our relatively well-grounded military-science-fiction tale spirals off into Vernor Vinge territory. You encounter an almost godlike race of multidimensional “electronic life forms” who send you hopscotching over vast distances in time and space. The last of the Myst comparisons fall away, as Mission Critical seems to lose interest in immersive environmental storytelling and becomes a much more typical Legend adventure game, full of character interactions and gallons and gallons of plot coming at you thick and fast. Instead of a single ship, you now hold the fate of the entire human race and, indeed, much of the multiverse in your hands.

This is the most problematic part of the game in many ways. The ideas being explored are certainly audacious, for all that they aren’t strikingly original for anyone versed in recent trends in literary science fiction at the time of Mission Critical‘s creation. Yet the contrast with what came before remains jarring, as the game turns into an exponentially less granular experience. It used to take a couple of dozen clicks to repair a breach in the hull of a spaceship; now it takes one or two to change the destiny of billions of sentient beings. My first instinct, born from researching the development history of countless other games, was that constraints of time and money had forced Legend to put the game on fast-forward when the project was already in midstream; Mission Critical would hardly be the first adventure game whose early environments are far more fully realized than its later ones. Mike Verdu confirmed that there was some of that going on, but also revealed that it was more planned and less improvised than I first suspected.

There was supposed to be a sense of increasing momentum, of the sense of scale increasing, the stakes increasing… that was a conscious decision. But you’re right that my ambition was too great for my budget and my schedule. I really hoped the latter part of the game would have the same production values and 3D assets as the first part. Instead things move more and more toward shorthand as you move toward the end.

I came to this upfront because we had to lay everything out then. Do I tell the story I want to tell and scrimp a bit on the assets and the fidelity toward the end? Or do I limit the ambition of the story? I decided I didn’t want to tell a story that was just about wandering around a spaceship fixing things. I made a bet that the first part of the game would ground the player in the world through fidelity and verisimilitude and immersion. Then they would forgive us for moving to a more shorthand sort of storytelling toward the end. Because at that point, what really matters is the story. You’re either hooked by the story or you’re not. If you are, you’re probably going to push on through, and what you’ll remember are the big ideas and the resolution more than the fact that Persephone was not rendered with the same level of fidelity as the Lexington and our cool AI environments were just paintings.

Legend had once hoped to release Mission Critical in the summer of 1995, but that date was eventually pushed back to November. It appeared at that time simultaneously with Shannara, their other game for the year. Neither was an outright commercial failure, but neither provided the commercial paradigm shift Legend had been looking for either.

Mission Critical didn’t sell a ton — maybe 70,000 copies, which meant that it probably broke even at best. Random House was disappointed. The hope had been that it would catapult us out of that range of 30,000 to 100,000 in sales. But we spent three times the budget and got essentially the same result. In that sense, it was a failure.

Yet Mission Critical, despite being so thoroughly of its time in terms of technology and approach, would prove oddly enduring in the memories of both its principal creator and the select group of gamers whom it touched. This lumpy amalgamation of full-motion video, Myst-style pre-rendered environments, real-time strategy, and the traditional Legend approach to interactive storytelling is an artifact from a time when games were not yet all sorted on the basis of gameplay genre alone, when a designer could begin with a narrative experience in mind and just go from there, employing whatever approach seemed best suited to bring his imaginative conceptions to life. Mike Verdu would go on to a high-profile career after Legend at companies like Electronic Arts, Zynga, Facebook, and now Netflix, but he would never again get the opportunity to be a gaming auteur like he was on Mission Critical.

It’s the thing I’ve created that’s lasted the longest. The story seemed to really strike a chord with some people. I would get emails from people saying I’d blown their mind, or it was the most immersive thing they’d ever played. When it reached somebody, it really reached them. But that wasn’t a huge number of people. As an artist, if you reach a small number of people in a profound way, is that better than reaching a million people in a very shallow way? Because this was the game I created that reached a few people in a profound way. The rest of the games I’ve created, especially in the latter part of my career, reached in some cases tens of millions of people, but in a light-touch kind of way.

From a creator’s standpoint, Mission Critical is one of the most satisfying things I’ve ever made. It astounds me, but people still play it. I’d always thought of computer games as an ephemeral medium — something you create that quickly becomes obsolete because the advance of technology makes it literally unplayable. People can experience it for a brief window of time, then all they have is their memories. I had resigned myself to that. But it astounds me now that people are still playing the game and posting reviews. This is a much more enduring medium than I thought.

I’ve been delighted that Mission Critical and some of the other Legend games have stood the test of time.

(Sources: This article is drawn in its virtual entirety from the recollections of Mike Verdu. I thank him for taking the time from his busy schedule to talk with me, and wish him all the best in his latest gig with Netflix.

Mission Critical is available as a digital purchase at GOG.com. It comes highly recommended.)