It’s always been a bit of a balancing act to decide which games I write about in detail here — a matter of balancing my level of personal interest in each candidate against its historical importance. In the early years of this project especially, when I still saw it as focusing almost exclusively on narrative-oriented games, I passed over some worthy candidates because I considered them somewhat out of scope. And now, needless to say, I regret some of those omissions.

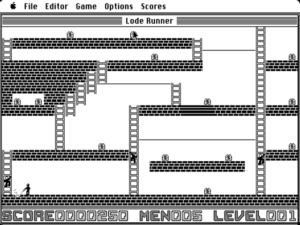

One of the games that’s been made most conspicuous by its absence here is Lode Runner, Doug Smith’s seminal action-puzzle platformer from 1983. “Iconic” is a painfully overused adjective today, but, if any game truly can be called an icon of its era, it’s this one. So, I decided to take the release of Lode Runner: The Legend Returns, a 1994 remake/re-imagining that does fit neatly into our current position in the historical chronology, as an opportunity to have a belated look back at the original.

In late 1981, Doug Smith was studying architecture and numerical analysis at the University of Washington in Seattle. Meanwhile he had a part-time job in one of the university’s computer labs, where he met two other students named James Bratsanos and Tracy Steinbeck, who were tinkering with a game they called Kong, a not so-thinly-veiled reference to the arcade hit Donkey Kong. Bratsanos had first created Kong the previous year on one of his high school’s Commodore PET microcomputers, and the two were now in the process of porting it to one of the university’s DEC VAX-11/780 minicomputers. Smith soon joined the effort. When their fellow students started to show some interest in what they were doing, they made the game publicly available.

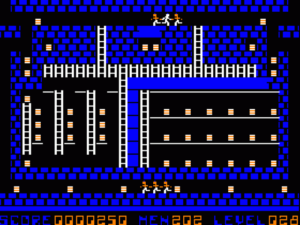

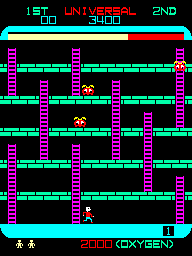

In Kong, you guided a little man through a single-screen labyrinth of tunnels linked by ladders, implemented entirely using monochrome textual characters; your man was a dollar sign, your enemies paragraph symbols. Armed only with a pick axe that was more tool than weapon, you must steal all of the gold that was lying around the place, whilst avoiding or delaying the guards who protected it, generally by digging pits into which they could fall. The group hid their game from the university’s administrators by embedding it into an otherwise broken graphing program. “‘Graph’ would prompt the user for a function,” remembers a fellow student named Rick LaMont, “then crap out unless the secret password was entered to play Kong.”

With its captive audience of playtesters in the form of the students who hung around the computer labs, the game grew organically as the weeks passed. Soon students were coming by only to play Kong; LaMont claims that “a ‘show process’ command would often report 80 percent of the users running ‘graph.'” Eager players began to queue up behind the university’s computer terminals, and Kong became a fixture of campus life, the University of Washington’s equivalent of what Zork had once been at MIT. Along the way, it gradually evolved from an arcade game into something that required as much thought as reflexes; the levels just kept getting more and more complex.

According to Smith, it was his eight-year-old nephew who convinced him to port the game to the Apple II; having visited the computer lab once or twice and seen it in action there, the little boy was decidedly eager for a version he could play at home. “After he bugged me enough,” said Smith in a 1999 interview, “one weekend I rewrote it for the Apple II, basically in three days.” This first microcomputer version was a copy of the DEC VAX version right down to its monochrome ASCII graphics. Smith made just one big change: he renamed the game Miner to avoid legal entanglements. After paying James Bratsanos $1500 for the rights to the game, he submitted it to Brøderbund Software, only to get a terse rejection letter back: “Thank you for submitting your game concept. Unfortunately, it does not fit with our product line.”

But, seeing how popular the game continued to be at the university, Smith decided to take another stab at it. He borrowed enough money to buy a color monitor and joystick for his Apple II, and programmed a second, much-improved version with color bitmap graphics and controls that took advantage of one of the Apple’s unique affordances: its joysticks had two buttons rather than the standard one, which in this case allowed the player’s avatar to drill to the left or right of himself without the player ever having to reach for the keyboard. In late 1982, Smith sent this new version to four different publishers, among them Brøderbund and Sierra. All of them knew as soon as they saw this latest version of the game that they wanted it for themselves. John Williams, the little brother of Sierra founder Ken Williams, and the company’s chief financial officer from the tender age of twenty, later claimed that he “almost lost his job” because he spent so much time playing the game Smith sent to them. But Smith wouldn’t end up publishing his game through Sierra. Instead he wound up entrusting it to Brøderbund after all.

Founded and run as a family business by a personable former lawyer and real-estate developer named Doug Carlston, Brøderbund would consistently demonstrate an uncanny talent for identifying exactly the software product that Middle America was looking for at any given moment, securing it for themselves, and then delivering it to their customers in the most appealing possible way. (At the risk of sounding unkind, I might note at this juncture that, whereas Ken Williams loved to talk about the mainstreaming of games and other software, the Carlston family talked less but proved more adept at the practical work of doing so.) In the years to come, this talent would result in a quantity of truly iconic Brøderbund titles out of all proportion to the relatively modest number of products which the company released in total: titles like Karateka, Carmen Sandiego, Bank Street Writer, The Print Shop, Prince of Persia, SimCity, Myst. But before any of them came Doug Smith’s game.

Brøderbund offered Smith a $10,000 advance and a very generous 23-percent royalty. And they also promised to get behind his game with the kind of concerted, professional marketing push that was still a rarity in the industry of that era. Showing a remarkable degree of restraint for his age as well as faith in his game’s potential, Smith signed with Brøderbund rather than accept another publisher’s offer of $100,000 outright, with no royalty to follow. He would be amply rewarded for his foresight.

For example, it was Brøderbund’s savvy marketers who gave Miner its final name. Well aware of the existence of another, superficially similar platform game called Miner 2049er, they proposed the alternate title of Lode Runner, as in “running after the mother lode.” Soon after choosing this new name that held fast the idea that the player was some sort or other of miner, they devised a more detailed fictional context for the whole affair that abandoned that notion entirely. It involved the evil Bungeling Empire, the antagonist of their 1982 hit Choplifter!:

You are a galactic commando deep in enemy territory. Power-hungry leaders of the repressive Bungeling Empire have stolen a fortune in gold from the people by means of excessive fast-food taxes. Your task? To infiltrate each of 150 different treasure rooms, evade the deadly Bungeling guards, and recover every chest of Bungeling booty.

In the spirit of this narrative, the hero’s pick axe became a laser drill.

Still, none of this background would be remembered by anyone who actually played the game. Instead the supposed Bungeling guards would become popularly known as “mad monks,” which their pudgy low-resolution shapes rather resembled. Doubtless plenty of imaginative young gamers made up new narratives of their own to fit the bizarre image of greedy monks chasing an intrepid adventurer up and down a maze of scaffolding dotted with gold.

Smith dropped out of university at the end of 1982, and worked closely with Brøderbund over the course of six months or so to polish his game in a concerted, methodical way, something that was seldom done at this early date. They helped him to tweak each of the 150 levels — some designed by Smith himself, some by the kids who lived around Smith’s family home, whom he paid out of his own pocket on a per-level basis — to a state of near-perfection, and arranged them all so that they steadily progressed in difficulty as you played through them one after another. And then Brøderbund encouraged Smith to polish up his level editor and include that as well.

Lode Runner got a rapturous reception upon its release in June of 1983, quickly becoming the best-selling product Brøderbund had ever released to that point; Smith was soon collecting more than $70,000 per month in royalties. If anything, its reputation among students of game design has become even more hallowed today. It stands out from its peers of 1983 like a young Glenn Gould in a beginner’s piano course.

That said, Lode Runner is not quite the sui generis game which its more enraptured devotees are sometimes tempted into claiming it to be. When James Bratsanos first created what would eventually become Lode Runner on the Commodore PET, he was according to his own testimony working from a friend’s description of an arcade game: “He didn’t explain it well, and I took creative liberties and assumed I understood what he meant. So for certain elements I completely misinterpreted it.” Bratsanos, an acknowledged non-gamer, may later have come to believe that the game his friend had been describing was Donkey Kong, and assumed that the major differences between that game and his stemmed from his youthful “misinterpretation” of his friend’s description of the former. But the chronology here doesn’t pass muster: Donkey Kong was first released in the summer of 1981, while Bratsanos is sure that he started working on his game, which originally went under the rather unpleasant name of Suicide, in 1980. Suicide became Kong only after Donkey Kong had been released and become an arcade sensation, and Bratsanos had started at the University of Washington the following fall.

So, what was it that his friend actually described to him back in 1980? The best candidate is Space Panic, a largely forgotten Japanese stand-up arcade game from that year which would seem to be the first ever example of the evergreen genre that would become known as the platformer. Not only did Space Panic have you running and climbing your way through a vertical labyrinth, but it also allowed you to dig holes in it to trap your enemies, just like Suicide, Kong, and finally Lode Runner. Space Panic was not a commercial success, perhaps because it asked for too much too soon from an audience still enthused with simpler fare like Space Invaders; it was reported that the average session with it lasted all of 30 seconds. But it does appear that it entranced one anonymous teenage boy enough that he told his buddy James Bratsanos all about it. And from that random conversation — from that butterfly flapping its wings, one might say — eventually stemmed one of the biggest games of the 1980s.

But if it isn’t quite an immaculate creation, Lode Runner is a brilliant one, a classic lesson in the way that fiendish complexity can arise out of deceptive simplicity in game design. It offers just six verbs — move left, right, up, or down; dig left or right — combined with only slightly more nouns — platforms of diggable brick or impenetrable metal, ladders, trap doors, overhead poles for shimmying, monks, treasures. And yet from this disarmingly short list of ingredients arises a well-nigh infinite buffet of devious possibility.

Although Lode Runner does retain some vestiges of its arcade inspirations in the form of a score and limited lives, it’s as much a puzzle or even a strategy game as an action game at heart. (Your lives are essentially meaningless in the end; you can save your progress at any point.) Playing each level entails first experimenting and dying — dying a lot — until you can devise a thoroughgoing plan for how to tackle it. Then, it’s just a matter of executing the plan perfectly; this is where the action elements come into play. The levels in Lode Runner are dynamic enough that getting through them doesn’t require stumbling across a single rote, set-piece solution envisioned by the designer; there’s space here for player creativity, space for variation, space for quick thinking that gets you out of an unanticipated jam — or that fails to do so just when you believe you’re on the brink of victory.

The levels build upon one another, each one training you for what’s still to come as it forces you to think about your limited menu of verbs and nouns in new ways. This sort of progressive design was not a hallmark of most computer games of 1983, and thus serves to make Lode Runner stand out all the more. The world would arguably have to wait until the release of DMA Designs’s Lemmings in 1991 to play another action-puzzler that was its equal in terms of design.

Just as in Lemmings, every single detail of Lode Runner‘s implementation becomes relevant as the levels become more complex, from the timing of events in the environment to the rudimentary but completely predictable artificial intelligence of the monks. Consider: the pits you drill are automatically filled in again after ten seconds, while monks climb out of pits into which they’ve fallen in just a few seconds. But what would happen if you could time things so that a pit is filled in while a monk is still inside it? The monk would get buried there permanently, that’s what, giving you a precious reprieve before the replacement who is spawned at the very top of the screen makes his way down to you once again. By the time you reach level 30 or so, you’ll be actively using the monks as your helpmates, taking advantage of the fact that they too like to pick up gold — for there’s now gold in places which you can’t reach, meaning you must depend on them to be your delivery men. Once one of them has what you need, you just need to make him fall into a pit, then walk on his head to steal the booty. Easy peasy, right? If you think so, don’t worry: there’s still 120 levels to go, each one more insidiously intricate than the last.

And then, when you’re done with all 150 levels, there’s still the level editor. Even by the standards of today, the original Apple II Lode Runner provides a lot of content. By the standards of 1983, its generosity was mind-boggling.

A phenomenal game by any standard, Lode Runner became a phenomenon of another sort in the months after its release. Doug Smith, a private, retiring fellow who loathed the spotlight, nevertheless became a household name among hardcore gamers, joining the likes of Bill Budge, Richard Garriott, and Nasir Gebelli as one of the last of the Apple II scene’s auteur-programmer stars. At a time when a major hit was a game that sold 50,000 copies, his game sold in the hundreds of thousands on the Apple II and in ports to the Commodore 64, the IBM PC, and virtually every other commercially viable computer platform under the sun. First it became the Apple II game of 1983; then it became the game of whatever year it happened to be ported to each other platform, collecting award after award almost by default. And then there was Japan.

Lode Runner appeared on the Macintosh soon after that machine’s release in 1984. Although the construction set was a a natural fit for that machine’s GUI, the actual game proved less satisfying. “What used to be a struggle strictly between the commando and the Bungeling guards is now also a battle between you and the [mouse] pointer,” wrote Macworld magazine. Such complaints would become something of a theme: Apple II purists insist to this day that no Lode Runner has ever played quite as well as the one that Doug Smith personally programmed for their favorite platform.

One of Doug Carlston’s smartest moves in the early days of Brøderbund was to forge links with the burgeoning software and gaming scene in Japan. He was particularly chummy with Yuji Kudo, the founder of Hudson Soft, Japan’s biggest software publisher of all. (A model-train enthusiast extraordinaire, Kudo took his company’s very un-Japanese name from his favorite type of steam locomotive.) The two men already had a deal in place to bring Lode Runner to Japan even before it was released in the United States. During the summer of 1983, it became one of the first ten games to be made available for the Nintendo Famicom — the videogame console that would later conquer the world as the Nintendo Entertainment System.

Like Wizardry before it and Populous after it, Lode Runner turned into that rarest of birds, a Western videogame which the Japanese embraced with all the fannish obsessiveness of which they’re capable — which is, to be clear, a lot of obsessiveness indeed. Before there was Super Mario Bros. to drive sales of Nintendo consoles all over the world, there was Lode Runner to get the ball rolling in Japan itself. Sales of the game in Japan alone topped 1 million in the first eighteen months, prompting one journalist to declare Lode Runner Japan’s new “national pastime.”

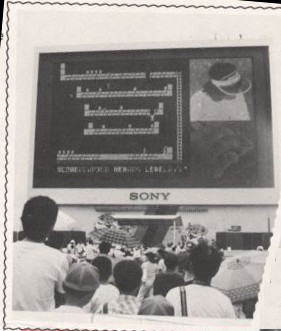

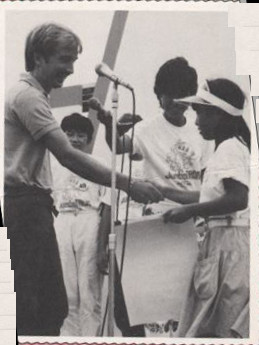

The country’s Lode Runner mania reached its peak in the summer of 1985, when Hudson Soft, Brøderbund, and Sony joined forces to sponsor a national competition in the game. Of the 3700 players between the ages of nine and fourteen who entered the competition, 50 became finalists, invited to come to Tokyo and play the game on what was at that time the largest video screen in the world, 86 feet in width. A slightly uncomfortable-looking Doug Smith, coaxed into the spotlight by Brøderbund’s marketers, presided over the affair and even agreed to join the competition. (He didn’t last very long.) “I like the people of Japan,” he said. “There’s an honesty among the people that is so refreshing — they would never think of pirating computer games, for instance.” (A more likely explanation for Lode Runner‘s high sales in Japan than the people’s innate honesty was, of course, the fact that piracy on the cartridge-based Famicom was a possibility for only the most technically adept.)

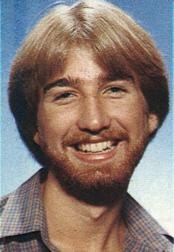

A rare shot of Doug Smith in person, giving prizes to the winners of the Japanese Lode Runner competition.

By decade’s end, Lode Runner‘s worldwide sales had topped 2.5 million copies. I can hardly emphasize enough what absurdly high figures these are for a game first sold on the humble Apple II.

When you take Brøderbund’s generous royalty and combine it with sales like this, then reckon in the fact that Lode Runner was essentially a one-man production, you wind up with one very wealthy young game programmer. Still in his early twenties, Doug Smith found himself in the enviable position of never having to work another day in his life. He bought, according to his friend Rick LaMont, “a Porsche 911 Carrera, a Bayliner speedboat, and a house in Issaquah.”

In the face of distractions like these, Doug Smith became one of a number of early Apple II auteurs, such as the aforementioned Bill Budge and Nasir Gebelli, who weren’t able to sustain their creative momentum as lone-wolf developers became teams and the title of game designer slowly separated itself from that of game programmer. He did provide Brøderbund with one Lode Runner sequel of a sort: Championship Lode Runner, with 50 new levels that had mostly been sent to the company by fans and that were (correctly) advertised as picking up in difficulty right where the first game had left off. But its technology and graphics were barely tweaked, and the decision to aim it exclusively at the hardest-core of the hardcore put a natural limit on its appeal.

After that, there followed several years of silence from Smith, off enjoying his riches and pondering the strange course his life had taken, from starving student to wealthy man of leisure in a matter of months. And truly, his is a story that could only have happened at this one brief window in time, when videogames had become popular enough to sell in the millions but could still be made by a single person.

Just as they did with Wizardry, the impatient Japanese soon took Lode Runner into their own hands, making and releasing a string of sequels in their country that would never appear elsewhere. But what ought to have been a natural ongoing franchise remained oddly under-served by Brøderbund in its country of origin; they released only one more under-realized, under-promoted sequel, for the Commodore 64 and Atari 8-bit line only, created by their recently purchased subsidiary Synapse Software without Smith’s involvement. Perhaps they were just too busy turning all those other products into icons of their era.

It wasn’t until 1994, when Brøderbund’s ten-year option expired and all rights to the game and its trademarks reverted to Smith, that anyone attempted a full-fledged revival in the United States. Irony of ironies, the company behind said revival was Sierra, finally getting their chance with a game that had slipped through their fingers a decade before. The project was driven by Jeff Tunnell, the founder of what was now the Sierra subsidiary known as Dynamix, who had just made the classic puzzler The Incredible Machine.

Lode Runner: The Legend Returns was a symbol of everything that was right and wrong with the games industry of the mid-1990s. Dynamix added beautiful hand-painted backgrounds and a stereo soundtrack to the old formula, but in the minds of many the new version just didn’t play as well as the old; it had something to do with the timing, something to do with the unavoidably different feel of a 1990s 32-bit computer game versus the vintage 8-bit variety — and perhaps something to do as well with Tunnell’s decision to add a lot more surface complexity to the elegantly simple mix of the original, including locks and keys, snares, gas traps, bombs, jackhammers, buckets of goo, and even light and darkness. The Legend Returns did reasonably well for Sierra, but never became the phenomenon that the original had been in its home country. And as for Japan… well, it now preferred homegrown platformers that featured a certain Italian plumber. The various revivals since have generally met the same fate: polite interest, decent sales, but no return to the full-blown Lode Runner mania of the 1980s.

Lode Runner: The Legend Returns definitely looks a lot more impressive than the original, which was far from an audiovisual wonder even in its own time. Opinions are at best divided, however, on whether it plays better. One can detect the influence of Lemmings 2: The Tribes in its diverse, ever-shifting collection of obstacles and affordances, but the end result is somehow less compelling.

Smith did return to playing an active role in the games industry in the 1990s, working as the producer of a couple of Nintendo games among other things. He disappeared from view once again after the millennium, occupying himself mostly with the raising of his five children. He died by suicide in 2014 at the age of 53.

(Sources: the book Software People: Inside the Computer Business by Douglas G. Carlston; Retro Gamer 111; Ahoy! of April 1986; A.N.A.L.O.G. of March 1984; Computer Gaming World of January/February 1983, October 1983, and March 1986; Electronic Games of June 1983 and January 1985; inCider of April 1984; InfoWorld of October 31 1984; Macworld of August 1985; MicroTimes of December 1984 and September 1985; Brøderbund News of April of Fall 1985; InterAction of Fall 1994. Online sources include IGN‘s 1999 interview with Doug Smith, Jeremy Parish’s eulogy to Smith, and a 1991 Usenet reminiscence by Rick LaMont.

Feel free to download the original Lode Runner and its manual for play in the Apple II emulator of your choice.)