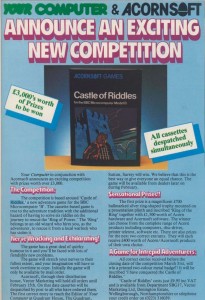

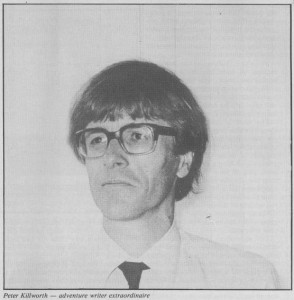

When Acorn Computer foundered on a financial iceberg in 1985, one of the first and saddest victims was Acornsoft, their software arm. Acornsoft was destined to go down into history first and foremost as the house that set British gaming on its head with Elite, but David Braben and Ian Bell, having already made their exodus to Firebird and taken their game with them, were hardly the ones most affected by the collapse. Those developers who didn’t have an easy escape hatch to hand had far more cause for worry. Among them were Peter Killworth and his colleagues from Cambridge University, who had over the previous few years brought a taste of the unique adventuring culture of their university’s Phoenix mainframe to the little BBC Micro by porting some of those games (Philosopher’s Quest, Kingdom of Hamil, Quondam, and Acheton) and writing new ones in their spirit (Castle of Riddles and Countdown to Doom).

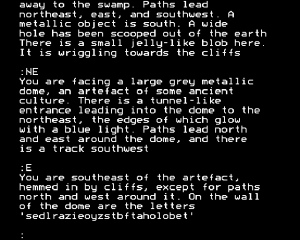

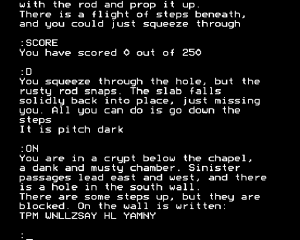

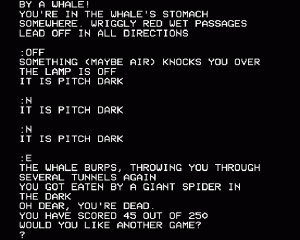

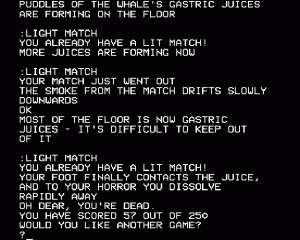

Making the sudden loss of a publisher even more disheartening was the fact that the Cambridge professors had only recently pulled off a technical coup for the ages. All of the Phoenix ports except the last had been just that, hand-made translations into ultra-compact BBC BASIC that were often accomplished only by making painful cuts to the original designs. The last game, however, was different. For it, John Thackray and David Seal chose the biggest whale of all, Acheton, the very first of the Phoenix games and by far the largest. They devised an interpreter to read and play the adventure’s compiled database file, written on the mainframe using their own T/SAL adventure-making programming language, on a 32 K BBC Micro equipped with a disk drive. Acheton‘s database alone was so large that it filled almost every byte of space on a disk side, forcing them to place the interpreter and boot code for the game on the other side of the disk. Showing a bit of mercy to players about to confront one of the most infamously difficult adventure games ever made, they used the extra space on the disk’s boot side for a graduated hint system that included more than 250 individual questions. That number gives some sense of the sheer scale of Acheton, as do its totals of more than 400 rooms to be mapped and more than 160 individual manipulable objects. Acheton was trumpeted by Acornsoft as the largest single adventure game ever written. It’s still amongst the leaders in that category today in terms of breadth if not depth of interaction; the ratio of rooms to objects alone illustrates what a very, very old-school game it is, its countless empty rooms as often as not grouped into fiendishly elaborate mazes of one stripe or another.

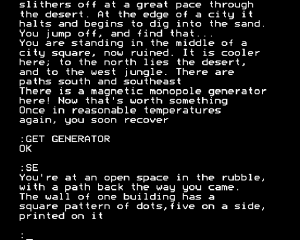

Olivetti, Acorn’s new owners, sold Acornsoft’s existing contracts and software to an outfit called Superior Software in 1986. Superior, however, wasn’t much interested in text adventures, so the Cambridge professors were eventually able to negotiate back ownership of the games they’d published through Acornsoft. In the meantime, they decided to bring another of the Phoenix games, Jon Thackray and Jonathan Partington’s Murdac, to the popular new Amstrad CPC line of computers. The CPC had a comparatively generous 64 K of memory, while Murdac was one of the smallest of the Phoenix games. These two facts together meant that an outside contractor named Richard Clayton, whose claim to fame was nothing less than having written the BASIC built into the CPC, was able to fit the entire Phoenix database file plus an interpreter into the memory of a cassette-based CPC. After an initial deal with Amsoft, Amstrad’s equivalent to Acornsoft, fell through, they signed a contract at last with Global Software to sell Murdac as Monsters of Murdac; the new prefix was apparently judged to give the game a bit more of that Dungeons and Dragons feel that the kids craved. Even in 1986 a Phoenix game like Murdac felt rather behind the times to many; this was after all the year that Magnetic Scrolls was knocking ’em dead with The Pawn. Amstrad Action columnist Steve Cooke, better known by his handle of “The Pilgrim” and in general one of the more thoughtful and perceptive voices in adventuring gaming, wrote a typical review, saying “it’s not hard to see why” Amsoft had decided to take a pass: “This is a text-only game of a rather old-fashioned nature where you trundle around underground solving puzzles and collecting valuable items.” He also took time like other reviewers to complain about Murdac‘s lack of an “examine” verb. This particular description, this particular complaint, and even this particular columnist would become all too familiar to the Cambridge colleagues in the years to come. For now, though, Monsters of Murdac didn’t make much impression, and the relationship with Global Software was soon severed. The third publisher would prove the charm.

That arrangement was born of an unsolicited phone call that Peter Killworth made to Brian Kerslake about the state of British educational software. It was certainly a topic that Kerslake knew a lot about, having made it into his life’s work. He and his wife Maddy, schoolteachers both, had formed an educational-software developer and publisher called Chalksoft back in 1982. For a few years they had cranked out software covering all sorts of subjects for many age groups, from ABC and basic arithmetic drills for grade schoolers to French, German, and Spanish practice for adult tourists. Chalksoft, however, had never quite found their footing with schools’ purchasing departments, by far the best and most reliable customers for this sort of thing, and had been swept away like Acornsoft by the British computer industry’s mid-decade travails. Undaunted, the Kerslakes were determined to take what they had learned and try again, this time under the name of Topologika Software.

In their initial conversation, it was Killworth who did most of the talking. Specifically, he was talking — or complaining — about a hugely popular educational text adventure called L – A Mathemagical Adventure, an effort at teaching basic concepts in mathematics that had been written by the Association of Teachers of Mathematics themselves and was now a fixture in British schools. Simply put, Killworth thought he could do better. If he could, replied Kerslake, Topologika would love to publish it. Peter Killworth seldom needed to hear a challenge like that twice. A few months later, he handed them Giant Killer.

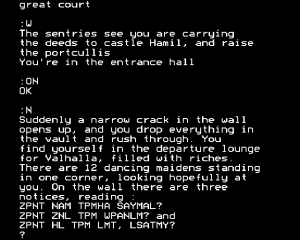

Published for the BBC Micro as Topologika’s first product in April of 1987, Giant Killer is “loosely based” on the old British fairy tale of Jack and the Beanstalk. The choice of names (sometimes also written as Giantkiller by Topologika and others) is obvious based on the subject matter, but may also be a sly dig at L, the educational giant Killworth intended to slay. That said, it’s not all that noticeably different from its inspiration and nemesis in form or content. Like L, it’s a simple text adventure whose various set-piece puzzles can all be clearly seen by a trained mind like Killworth’s as mathematical “investigations” exploring various fundamental properties. For a decidedly untrained mind like mine, they’re just a pretty good collection of logic puzzles, a few of them trivial, most of them straightforward but enjoyable, one or two quite tricky even for an adult (the bottle-sorting puzzle that turns up early bogs me down every time). Surprisingly in light of the reputation of its creator, Giant Killer is if anything somewhat simpler to get through than L, certainly at least noticeably more linear. Occasional references to “Venn cubes” and the like aside, the game never beats you over the head with the ideas you’re allegedly learning. It’s enough to make you wonder what really separates this game from lots of other abstractly puzzley text adventures beyond the extensive manual, meant for teachers, that carefully steps through every stage and puzzle in the game. I tend to want to say that Giant Killer teaches logical thinking more so than mathematics per se. But then I suppose some would argue that the two are one and the same.

Whatever the nature of its educational value, Giant Killer immediately became very, very popular, joining its rival L as a fixture for many years in schools across the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia. Like The Oregon Trail in the United States, these games are inescapable memories for Britons who attended primary school from the late 1980s to well into the 1990s. For the Kerslakes, Giant Killer became exactly the sort of reputation-establishing title they had been unable to find as Chalksoft, paving the way to the sustained success of Topologika as an educational publisher; they wouldn’t bring the company in for a soft landing until a quarter-century later. Giant Killer proved so popular that Topologika not only added to their catalog versions for many other platforms but also an add-on “support disk,” which presented the more intricate puzzles in graphical form for students to tinker with on the computer in lieu of pencil and paper before returning to the main game to enter their solutions.

Ironically, Giant Killer, by an order of magnitude the most widely played game to come out of the Phoenix adventuring culture, has been largely overlooked or dismissed in histories of that culture. While the original BBC Micro version of the game was done in BASIC on that machine itself, the database used in the ports was rewritten in the T/SAL adventure language on the Phoenix mainframe and run on each target machine through an interpreter. Whatever else it is, it’s very clearly an adventure in the Phoenix tradition, if also a much, much gentler experience than any of its stablemates.

With Giant Killer proving to be such a rousing debut for Topologika the educational publisher, the Kerslakes were more than happy to provide Killworth and his colleagues a stable home at last for their other adventure games as a sideline. In that first year of 1987 alone Topologika republished four of the old Acornsoft titles, whose rights the Cambridge professors had by now been able to secure again: Philosopher’s Quest, Kingdom of Hamil, Acheton, and Countdown to Doom. They were even able to boast that three of the four were “new and expanded” versions. The disk-based interpreter that Seal and Thackray had developed for Acheton allowed them to move the full versions of Philosopher’s Quest (known as Brand X on the mainframe) and Kingdom of Hamil onto microcomputers directly from the Phoenix mainframe, while Killworth rewrote and expanded Countdown to Doom in T/SAL for its Topologika release.

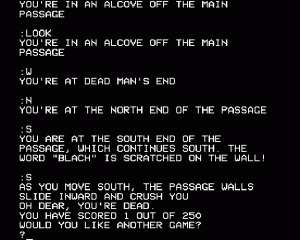

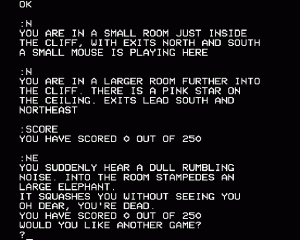

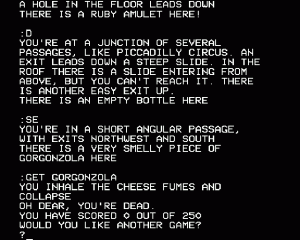

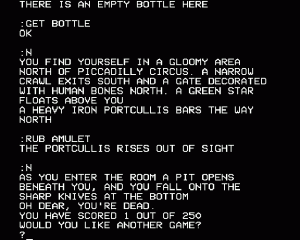

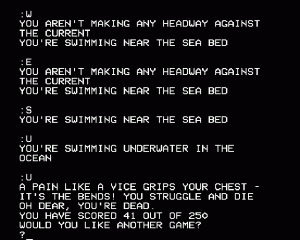

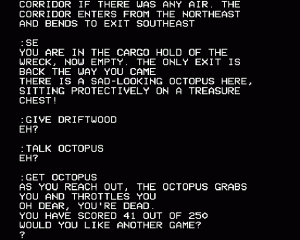

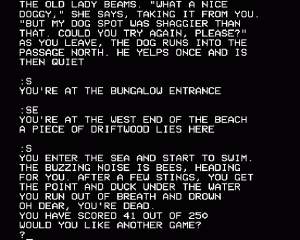

These games with their cool intellectualism and rigorous minimalism paddled defiantly against the current of adventure games in the late 1980s, which were evolving to place ever more emphasis on story, texture, and accessibility via more and more text, better and better parsers, and better and more pictures that would soon come to replace text and parsers entirely. It’s jarring just to see a review of one of the Topologika games in a magazine filled with pictures of scantily-clad barbarian maidens, well-oiled action heroes, and explosions galore. The people excited by those things, one senses, just aren’t likely to get too excited about spending hours plotting out the mechanics of intricate spatial and mathematical puzzles described in a bare few, albeit generally well-chosen sentences. The problem of an audience being stolen away by other, shinier genres was admittedly one that most text adventures were beginning to face, but with the Phoenix games it was exacerbated to the extreme; these games could be off-putting to even the most dedicated fans of the genre. Most of the reviews hammered on the same few phrases: “old-fashioned,” “no story,” “poor parser,” “difficult puzzles,” and, most of all, “no examine,” which alone could be read as shorthand for everything most adventure-game players wanted from their games by 1987 that the Phoenix games adamantly refused to give them; I’ll try to explain why in just a moment.

But one thing made the Phoenix games unique in comparison to other sketchily implemented games: their sketchiness arose from — or at least was claimed to arise from — a considered design position rather than a simple lack of time, will, resources, or technical skill. That’s perhaps a bit convenient given that these games were made on a shoestring compared to the likes of Magnetic Scrolls or even Level 9, much less Infocom, but it was nevertheless a position that Killworth and even Brian Kerslake were prepared to argue with considerable force and passion. A fascinating debate erupted between the Topologika crew and “Pilgrim” Steve Cooke after the latter gave Philosopher’s Quest and Countdown to Doom less than glowing reviews, hitting in the course of them on most of the themes listed in my previous paragraph. Turning to the December 1987 issue of Amstrad Action, I want to consider a letter Killworth wrote to Cooke in response to his reviews along with Cooke’s own replies at some length because I think they offer much food for thought, not only in the context of the Phoenix games but of the art of interactive fiction in general.

Killworth makes some decidedly dubious assertions in his letter, such as the claim that recently developed conveniences like “ramsave,” used to quickly stash an undo point in memory, are unnecessary in Topologika games because saving is “well-nigh instant anyway, since this is a disk-based game.” To that one can only reply that: a) users of the single-drive 8-bit systems that made up so many of Topologika’s customers, forced as they were to swap disks twice and enter a filename with every save, apparently had a different definition of “instant”; and b) it’s always a dangerous practice under any circumstances for a software developer to lecture users on why they really don’t need the feature they’ve just requested.

Killworth’s assertion that better parsers don’t allow more complex and interesting puzzles also strikes me as rather transparently ridiculous.

The original mainframe Zork is a good example. It’s still around, and in cut-down micro versions, not because of its parser (which has, as do all fancy parsers, lot of infelicities — I know of only one puzzle in one adventure that needs a fancy parser); not because of its graphics (it has none); but because it’s witty, with some interesting puzzles. Well, we strive for wittiness, but that’s in the eye of the beholder; but we do achieve interesting puzzles.

I can only speculate that, if Killworth hadn’t seen more than one example of better parsers leading to better puzzles in Infocom’s games in particular, he hadn’t played very many (any?). The Phoenix games are often remarkable for how many interesting puzzles they are able to coax out of their limited parsers and world models, but this is merely a product of artful designing around the engine’s constraints, not proof that better parsers don’t allow more varied and interesting puzzles and gameplay in general. Cooke’s very reasonable response:

I must disagree heartily on this one. I agree that the majority of games (even those claiming fancy parsers) can be satisfactorily played using simple inputs. This is, however, a point against poorly designed games, and not against complex parsers. To give a few examples of powerful parsing adding considerably to gameplay, I would cite (1) Level 9’s ability to command a character to carry out actions while you get on with something else; (2) the relative positioning in Magnetic Scrolls games, with solutions such as “smear x on y” or “look under z”; (3) for sheer convenience, the “go to,” “follow,” and “find” commands now used by some companies; and (4) as a personal favourite, the use of the “hide” command in Infocom’s Suspect.

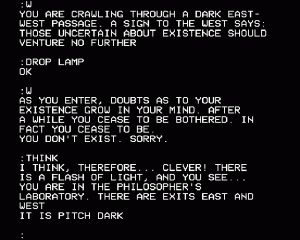

But Killworth is on firmer ground in at least some senses when we come to the oddly specific topic to which the whole debate surrounding the Topologika games seems to continually return: their lack of an “examine” verb. Killworth:

Much of your review of my games Countdown to Doom and Philosopher’s Quest is taken up with the complaint that you expect “examine” to work in all games. My philosophy has always been — and always will be — that the computer is your senses and hands. Anything that you see should and must be passed on to the player immediately. I can’t see the point of:

There is an X here.

Examine X.

You find a Y.

when

There is an X here. It has a Y attached… (or whatever)

is what you, the player, actually see when you look at the blessed thing. Another example which gets my goat is:

There is a piece of wood here.

Examine wood.

It is Y-shaped, and would make a fine catapult if it had elastic.

(almost verbatim from one bestselling game). Why not:

There is a Y-shaped piece of wood here. It resembles a catapult without the elastic.

or words to that effect? So I and my colleagues have always eschewed the use of “examine” — it’s a waste of player time and furthermore is really programmer dishonesty: it creates a potential puzzle “free” because the player might forget to do an “examine.”

Cooke’s response:

I quite understand your argument and am even inclined to agree with you — there’s no point in an “examine” that simply serves to draw out the gameplay to no real purpose. However, I feel that in real life we do “examine” objects to see if there is more to them than meets the eye, and in an adventure I believe that occasionally the “examine” command is vital in enhancing the atmosphere of a game. A good example would be the books in the library in Guild of Thieves, where you can “read” (i.e., examine) a large number of objects and have fun doing so. However, there’s no doubt that some puzzles have come to depend too much on the “examine” command, like the catapult you mention. On the other hand, I feel that excluding the command altogether, as you do, is moving too far to the other extreme.

Applied to games in the Phoenix style, I find Killworth’s argument that “examine” is unnecessary convincing enough, even as I find unconvincing his argument that a storyworld without “examine” better simulates our experience of reality. The fact is that we do usually choose where to focus our attention when we enter a new space that’s not entirely or nearly empty. The important difference between Topologika games and those from others was that rooms in the former were entirely or nearly empty as an almost universal rule, but the latter were beginning by this point to simulate richer, more complex spaces. Thus the former don’t need “examine,” but the latter do. I think this is an important distinction to consider because it moves us closer to understanding what’s really going on in this debate in general.

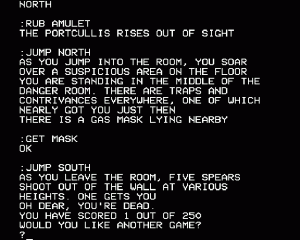

Cooke seemed unable to keep himself from connecting the lack of “examine” to everything else he didn’t like about the Topologika games. See for example the prevalence of unclued sudden deaths, like this one in Countdown to Doom:

In one location near the start, there’s a blob-like thing that slithers across the path towards a cliff. If you just watch it, it soon disappears over the edge (presumably forever) and since you assume that it has some significance in the game you feel reluctant to let it go. You can’t “examine” it, so the only thing to do is to “get” it. This is instantly fatal.

Killworth’s reply:

On the subject of “examine” and the “dangerous blob,” fatal to get: what information would you expect “examine blob” to produce that would tell you that touching it is fatal? Tell me what there is about an earthly jellyfish (which would be long extinct by the time Doom happens) that would tell you not to touch it if you’d never come across one!

This continued fixation on what would happen in the real world is rather missing the point entirely, especially given that rigorous realism is hardly among the Phoenix games’ strengths. The real point is of course that this sort of sudden death is just annoying and cruel, as many other game designers were coming to understand at last by 1987. Cooke:

My concern about the fatal blob was not altogether due to the absence of an “examine” command and if I gave that impression (I don’t have the review to hand) I apologise for being misleading. It’s just that I have never been enamoured of having curiosity in a game rewarded with death without some form of warning. Some software houses get round this by asking quite directly, “Do you wish to continue?” or “Are you sure you want to do that?”. Although a bit feeble, this at least gives the player cause for thought. Better by far to introduce the warning into the gameplay. For example — if there was a stick to hand I might use it to prod the blob first, whereupon seeing the stick sizzle and burst into flame would enable me to save my skin and congratulate myself on being a clever dick into the bargain!

It’s one of Killworth’s concluding statements that I find to be his most perceptive and most interesting, being as cogent an explanation as we’re likely to find of why he and Cooke so often seem to be talking past one another.

Looking back at your comments, what I think I read is that you like to “live” in the games you play as a primary motive, while solving them is secondary. For example, you like to talk to characters; I don’t. I believe that good plotting and good puzzles are what keep a game going over the years.

It’s the old conundrum of the crossword versus the narrative — game as abstract puzzle or game as embodied experience. Killworth remained doctrinally, ideologically wedded to the former while Cooke was eager to see games in the latter light. Read in the light of this reality, this debate that keeps returning over and over to “examine” takes on a whole new level of meaning. Cooke complains about the lack of an “examine” command. Killworth responds, reasonably enough, that there’s really no need for an “examine” command in Topologika games. Cooke remains unsatisfied because a game so minimalist that it doesn’t need “examine” isn’t a game he wants to play. The lack of “examine,” in other words, isn’t the disease but a symptom of the deeper problem that Cooke can’t quite articulate. Most gamers shared his preference for more experiential games; the medium in general had been moving in this direction for years. And that in a nutshell is why Topologika adventure games weren’t ever going to set the world on fire.

Subsequent exchanges among Cooke, Killworth, and eventually also Brian Kerslake, which continued for some eighteen months, grow progressively more petty and less illuminating, serving mainly as an object lesson to creators that there’s little to be gained in attempting to rebut criticism. In the meantime, new Topologika adventures continued to appear. Killworth wrote and published two sequels to Countdown to Doom, Return to Doom and The Last Days of Doom, in 1988 and 1990 respectively, and in 1989 came Jonathan Partington’s Shakespeare-themed Avon, which had been available to Phoenix users for seven years. Both Avon and The Last Days of Doom also included an additional “B-side” adventure: a republished Murdac in the case of the former, another old Phoenix game called Hezarin in that of the latter. Topologika funded ports of the T/SAL interpreter and thus their entire adventure catalog to quite a number of disk-drive-equipped platforms other than the BBC Micro, including the Amstrad CPC and PCW, the IBM PC, the Sinclair Spectrum, the Acorn Electron and Archimedes, and the Atari ST. The end of the line didn’t come until 1992, with the publication of Spy Snatcher, a Thackray/Partington game that had been one of the last new adventures made available to players on the Phoenix mainframe circa 1988. I’d be tempted to also name Spy Snatcher as the last all-text game to be sold as a conventional boxed product on store shelves, except that by 1992 the Topologika games were so poorly distributed that just about the only way to get one was to call up Topologika themselves and ask for one. All of the old adventures remained notionally available, in the sense that you wouldn’t find them in Topologika’s catalogs but they would sell you a copy from their warehouse stock if you asked them, until 1999, when Graham Nelson and Adam Atkinson convinced the Kerslakes and the Cambridge professors to release the whole collection as freeware. Those gentlemen and others have since done stellar work preserving not only the Topologika versions but also the Phoenix mainframe originals.

Even in their commercial heyday, such as it was, the Topologika adventures were never more than cult titles, beloved by an enthusiastic but tiny base of players. And by “tiny” I mean really tiny; some later Topologika adventures never made it to four digits in total sales. Given this, and given that they were downright reactionary in their refusal to evolve with the times — one can’t help but think of former silent-movie stars railing against the talkies when reading some of Killworth’s comments — you might well be wondering why I’ve chosen to give them as much attention as I have. The historical argument is that T/SAL represents the first specialized adventure-authoring language to be made available to the public — assuming your definition of “public” is inclusive enough to stand in for “people with access to Cambridge’s Phoenix mainframe” — and the first game made with it, the monstrous Acheton, was also the first text adventure to be made in Britain, the starting point of a whole national tradition. As such, the later history of T/SAL and the games it spawned is well worth documenting.

The aesthetic argument is more subtle but also more compelling. The Phoenix games represent the most uncompromising examples ever of a certain school of text-adventure design that would see the genre as one of the world’s ultimate tests of logic, organizational ability, and sheer dogged willpower. You don’t so much play a Phoenix game as you assault it, problem by problem, maze by maze, restarting again and again to optimize your play and mapping out meter by hard-fought meter your path to victory against a game that wants to kill you every chance it gets. That’s not quite what most of us are looking for when we sit down to play a game. Yet there’s a certain purity to the Phoenix games’ refusal to allow distractions like story texture and player convenience to obscure their diamond-hard spine. They’re like the Lloyd’s building in London, pipes and wiring exposed to see and celebrate. While they are extremely difficult and gleefully unforgiving, they also contain surprisingly little of the bullshit that normally marks such minimalist efforts: no guess the verb, no random puzzle solutions pulled out of thin air. The logic is there, somewhere; it’s just a matter of finding it. According to their own lights if not those of our modern times, they’re playing tough — very tough — but fair with you.

If that sounds like something for you, I recommend you start with Giant Killer and see how it goes. The other Phoenix games share more than a little of Giant Killer‘s intellectual — one might even say pedagogic — flavor, and Giant Killer‘s preferred type of puzzle will be very familiar to anyone who has experience with those other games: intricate set-pieces often spanning many rooms that demand pencil and paper and systematic, holistic thought. The antithesis, in other words, of “use this object here.” It’s just that those other Phoenix games, having been written by graduate students and PhDs in some of the most difficult disciplines in the world for their peers in one of the most demanding universities in the world, are much, much more rigorous exercises. And of course Giant Killer doesn’t kill you without warning every other turn. There is that.

Still, playing it should give you a good idea of whether you want to explore further. If you’re one of the few on the right wavelength, you’ve got months or years of masochistic fun to look forward to. And if not, you can breathe a sigh of relief, safe in the knowledge that no one dares make ’em like this anymore.

(Sources: 8000 Plus of June 1988, July 1988, December 1988, February 1989, April 1989, August 1989, November 1989, and January 1990; Amstrad Action of December 1985, August 1986, November 1987, December 1987, February 1988, September 1988, December 1988, February 1989, April 1989, December 1989, June 1990, November 1990; Crash of May 1988, June 1988, July 1988, and August 1988; Games Machine of September 1988 and September 1990; Your Sinclair of July 1988; Home Computing Weekly of April 12 1983, May 24 1983, September 27 1983, October 30 1984, April 2 1985, April 23 1985, and April 30 1985; Laser Bug of January 1983, June 1983, July/August 1983, and September 1983; ZX Computing of April/May 1985; Acorn Programs of August/September 1984; Acorn User of December 1984; Computer and Video Games of March 1985. See also the feature on the Phoenix games in SPAG Magazine #58.

To play Giant Killer, you can either download the original BBC Micro version from here or the MS-DOS port from Topologika’s ghost of a home page. The latter will unfortunately not run on 64-bit versions of Windows, so you’ll need to use DOSBox or something similar to get it going. The other games discussed in this article are all available on the IF Archive in one form or another.)