Please bear with me as I begin today with an anecdote from Beatles rather than gaming fandom.

Paul McCartney was having a rough time of it in 1973, three years after the Beatles’ breakup. He’d been thrown off balance by that event more than any of his band mates, and had spent the intervening time releasing albums full of far too many flaccid, underwritten songs, which the critics savaged with glee. They treated Wings, the new band he had formed, with the same derision, mocking especially the inclusion of Paul’s wife Linda as keyboard player. (“What do you call a dog with wings?” ran one of the uglier misogynist jokes of the time. “Linda!”) Then, just as it seemed things couldn’t get any worse, two of the three members of Wings who weren’t part of the McCartney family quit just as they were all supposed to fly to Lagos, Nigeria, to record their latest album.

It ought to have been the straw that broke the camel’s back. But instead, Paul, Linda, and their faithful rhythm guitarist Denny Laine went to Nigeria and delivered what many still regard as the finest album of McCartney’s post-Beatles career. “Paul thought, I’ve got to do it. Either I give up and cut my throat or get my magic back,” said Linda later. He did the latter: Band on the Run marked the return of the Paul McCartney who had crafted the astonishing medley that closed out Abbey Road, that parting shot of the greatest rock band ever. As Nicholas Schaffner wrote in The Beatles Forever, “Band on the Run more than sufficed to dispel the stigma of all that intervening wimpery. And the aging hippies all said: McCartney Is Back.”

I tell this story now because I had much the same feeling when I recently played Superhero League of Hoboken, Steve Meretzky’s game from 1994: “Meretzky Is Back.” And a welcome return it was.

Meretzky, you see, spent the period immediately following the breakup of Infocom in 1989 pursuing his own sort of peculiarly underwhelming course. The man who had strained so hard to bring real literary credibility to the medium of the adventure game in 1985 via A Mind Forever Voyaging spent the early years of the 1990s making lowbrow sex comedies seemingly aimed primarily at thirteen-year-old boys. Spellcasting 101: Sorcerers Get All the Girls, the first of the bunch, was defensible on its own merits, and certainly a solid commercial choice with which to kick-start Legend Entertainment, the company co-founded by former Infocom author Bob Bates with the explicit goal of becoming the heir to Infocom’s legacy. By the time of Spellcasting 201 and Spellcasting 301, however, the jokes were wearing decidedly thin. And the less said the better about Activision’s Leather Goddesses of Phobos 2, the comprehensively botched graphical sequel to arguably Meretzky’s best single Infocom text adventure of all. By 1992, it was time for a change. Oh, boy, was it time for a change.

Thus it was a blessing for everyone when Meretzky decided not to make the fourth game in what had been planned as a Spellcasting tetralogy, decided to do something completely different for Legend instead. The change in plans was readily accepted by the latter, for whom Meretzky worked from home on a contract basis. For, in a surprising indication that even the timeless marketing mantra that Sex Sells isn’t complete proof against a stale concept, sales of Spellcasting 301 hadn’t been all that strong.

The concept for Meretzky’s next game was fresh in comparison to what had come immediately before it, but it wasn’t actually all that new. In 1987, after finishing Stationfall for Infocom, he’d prepared a list of eight possibilities for his next project and circulated it among his colleagues. On the list was something called Super-Hero League of America:

When Marvel Comics asked if we’d be interested in a collaboration, I thought, Steve, old buddy, old pal, you could think up a lot more interesting and weird and fun superheroes than those worn-out boring Marvel Comics superheroes. Such as Farm Stand Man, who can turn himself into any vegetable beginning with a vowel. Dr. Madmoiselle [sic] Mozzarella, who can tell the toppings on any pizza before the box is even opened! I see this as a Hitchhiker’s/Rashomon type game in which you can play your choice of any of half a dozen superheroes. The story would be slightly different depending on which one you chose. If you elected to portray Annelid Man (able to communicate with any member of the worm family), you wouldn’t command as much respect as Dr. Asphalt (able to devour entire eight-lane highways), and the other superheroes wouldn’t obey you as readily. Potential for lots of interesting puzzles. Possible RPG elements.

“I like this!” scribbled one of his colleagues on the memo. “The superheroes shouldn’t be so silly, though… maybe?” But in the end, Meretzky wound up doing the safest project on the list, yet another Zork sequel. After releasing a whole pile of unique and innovative games over the course of 1987, to uniformly dismal commercial results, Infocom just didn’t feel that they had room to take any more chances.

Still, the idea continued to resonate with its originator, even through all of the changes which the ensuing five years brought with them. In late 1992, having decided not to do another Spellcasting game, he dusted it off and developed it further. He had the brilliant brainstorm of setting it in Hoboken, New Jersey, a real town of 35,000 souls not without a record of achievement — it’s the birthplace of baseball, Frank Sinatra, and Yo La Tengo — but one whose very name seems somehow to hilariously evoke its state’s longstanding inferiority complex in relation to its more cosmopolitan neighbor New York. Hoboken was the perfect home for Meretzky’s collection of low-rent superheroes with massive inferiority complexes of their own. Even more notably, the “possible RPG elements” of the first proposal turned into a full-fledged adventure/CRPG hybrid, a dramatic leap into unexplored territory for both Mereztky and Legend.

It was new territory for Meretzky the game designer, that is, but not for Meretzky the game player: he had long been a fan of CRPGs. Among the documents from the Infocom era which he has donated to the Internet Archive are notes about the games from other companies which Meretzky was playing during the 1980s. One finds there pages and pages of lovingly annotated maps of the likes of Might and Magic. Meretzky:

I’d been wanting to make an RPG for many years. But I thought that the usual Tolkienesque fantasy setting and trappings of RPGs had been done to death, and it occurred to me that superheroes was an excellent alternate genre that worked well with RPG gameplay, with superpowers substituting for magic spells. I originally planned to make it a full RPG, but Legend had never done anything that wasn’t a straight adventure game and were therefore nervous, so the only way I could convince them was to make it an RPG/adventure hybrid.

Meretzky’s characterization of Legend here is perhaps a touch ungenerous. They were a small company with limited resources, and were already in the process of moving from a parser-based adventure engine to a point-and-click one. Adapting it to work as a CRPG was a tall order.

Indeed, Superhero League of Hoboken remained in active development for more than eighteen months, longer than any Legend game to date. In the end, though, they succeeded in melding their standard graphic-adventure interface to a clever new combat engine. By the time the game was released in the summer of 1994, Meretzky had already moved on from Legend, and was working with fellow Infocom alum Mike Dornbrook to set up their own studio, under the name of Boffo Games. As a parting gift to Legend, however, Hoboken could hardly be beat. It had turned into a genuinely great game, Meretzky’s best since Stationfall or even Leather Goddesses of Phobos.

It takes place in a post-apocalyptic setting, a choice that was much in vogue in the mid-1990s; I’m now reviewing my third post-apocalyptic adventure game in a row. But, whereas Under a Killing Moon and Beneath a Steel Sky teeter a little uncertainly between seriousness and the centrifugal pull that comedy always exerts on the adventure genre, Hoboken wants only to be the latter. It’s extravagantly silly, so stupid that it’s smart — Meretzky at his best, in other words.

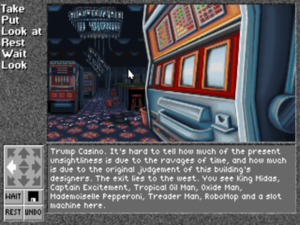

The premise is that a considerable percentage of the population have become “superheroes” in the wake of a nuclear war, thanks to all of the radiation in the air. But most of the actual superpowers thus acquired are, shall we say, rather esoteric. For example, you play the Crimson Tape, whose superpower is the ability to create organizational charts. That makes you ideal for the role of leader of the Hoboken chapter of the Superhero League. Your gang there includes folks like the Iron Tummy, who can eat spicy food without distress; the ironically named Captain Excitement, who puts others to sleep; Robo Mop, who can clean up almost any mess; Tropical Oil Man, who raises the cholesterol levels in his enemies; the holdover from the Infocom proposal Madam Pepperoni, who can see inside pizza boxes; and my personal favorite, King Midas, who can turn anything into a muffler. (For my non-American readers: “Midas” is the name of a chain of American auto-repair shops specializing in, yes, mufflers.) Some of these superpowers are more obviously useful than others: Captain Excitement’s power, for example, is the equivalent of the Sleep spell, that staple of low-level Dungeons & Dragons. Some of them are sneakily useful: the game’s equivalent of treasure chests are pizza boxes, which makes Madam Pepperoni its equivalent of your handy trap-detecting thief from a more ordinary CRPG setting. And some of the superpowers, including your own and that of many others, are utterly useless for fighting crime — until you stumble upon that one puzzle for which they’re perfect.

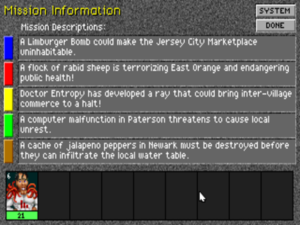

The game has a smart and very satisfying structure, playing out in half a dozen chapters. At the beginning of each of them you’re given a to-do list of five tasks in your superhero headquarters. To accomplish these things, you’ll naturally have to venture out into the streets. Each chapter takes you farther from home and requires you to explore more dangerous areas than the last; by its end, the game has come to encompass much of the Northeastern Seaboard, from Philadelphia to Boston, all of it now plagued by radiation and crime.

In the Spellcasting games, Meretzky had a tendency to ask the player to do boring and/or irritating things over and over again, apparently in the mistaken impression that there’s something intrinsically funny about such blatant player abuse. It’s therefore notable that Hoboken evinces exactly the opposite tendency — i.e., it seeks to minimize the things that usually get boring in other CRPGs. Each section of the map spawns random encounters up to a certain point, and then stops, out of the logic that you’ve now cleaned that neighborhood of miscreants. I can’t praise this mechanic enough. There’s nothing more annoying than trying to move quickly through explored areas in a typical CRPG, only to be forced to contend with fight after mindlessly trivial fight. Likewise, the sense of achievement you get from actually succeeding in your ostensible goal of defeating the forces of evil and making a place safe again shouldn’t be underestimated. Among CRPGs that predate this one, Pool of Radiance is the only title I know of which does something similar, and with a similar premise behind it at that; there you’re reclaiming the fantasy village of Phlan from its enemies, just as here you’re reclaiming the urban northeast of the United States. Hoboken is clearly the work of a designer who has played a lot of games of its ilk — a rarer qualification in game design than you might expect — and knows which parts tend to be consistently fun and which parts can quickly become a drag.

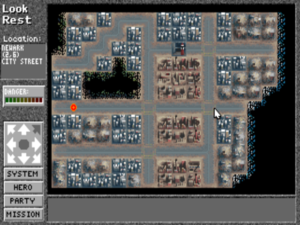

You explore the city streets — this CRPG’s equivalent of a dungeon — from a top-down perspective. This interface yields to a separate interface for fighting the baddies you encounter, or to the first-person adventure-game interface when you wander onto certain “special” squares.

The combat system makes for an interesting study in itself, resembling as it does those found in many Japanese console CRPGs more than American incarnations of the genre. It’s simple and thoroughly unserious, like most things in this game, but it’s not without a modicum of tactical depth. Each round, each character in your party can choose to mount a melee attack if she’s close enough (using one of an assortment of appropriately silly weapons), mount a ranged attack if not (using one of an equally silly assortment of weapons), utilize her superpower (which is invariably silly), or assume a defensive stance. Certain weapons and powers are more effective against certain enemies; learning which approaches work best against whom and then optimizing accordingly is a key to your success. Ditto setting up the right party for taking on the inhabitants of the area you happen to be exploring; although you can’t create superheroes of your own, you have a larger and larger pool of them to choose from as the game continues and the fame of your Hoboken branch of the Superhero League increases. But be careful not to mix and match too much: heroes go up in level with success in combat, so you don’t want to spread the opportunities around too evenly, lest you end up with a team full of mediocrities in lieu of at least a few high-level superstars.

Combat on the mean streets of Hoboken. Here we’re up against some Screaming Meemies (“members of a strange cult that worships the decade of the 1970s, identified by their loud cry of ‘Me! Me!'”) and Supermoms (“Bred for child-bearing and child-rearing characteristics by 21st-century anti-feminist fundamentalists”).

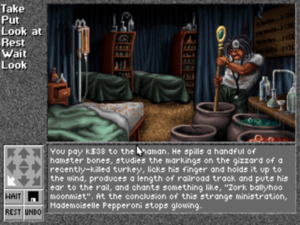

As you explore the streets of the city, you stumble upon special locations that cause the adventure side of the game’s personality to kick in. Here the viewpoint shifts from overhead third-person to a first-person display, with an interface that will look very familiar to anyone who has played Companions of Xanth, Legend’s first point-and-click graphic adventure. In addition to conversing with others and solving puzzles in these sections, you can visit shops selling weapons and armor and can frequent healers, all essential for the CRPG side of things. That said, the bifurcation between the game’s two halves remains pronounced enough that you can never forget that this is a CRPG grafted onto an adventure-game engine. Your characters even have two completely separate inventories, one for stuff used to fight baddies and one for stuff used to solve puzzles. Thankfully, each half works well enough on its own that you don’t really care; the adventure half as well marked a welcome departure from Meretzky’s recent tendency to mistake annoyance for humor, whilst offering up some of his wittiest puzzles in years.

Curing a disease contracted in the CRPG section by visiting a healer found, complete with gratuitous Infocom references, in the adventure section.

But by my lights the funniest part of the game remains the rogue’s gallery of superheroes and villains — especially the latter. These provided Meretzky with an opportunity to vent his frustration on a wide array of deserving targets. Some are specific, like Transistor Jowl, a clone of Richard Nixon, right down to his parting line of “You won’t have Transistor Jowl to kick around anymore” (delivered perfectly in the CD-ROM version by voice actor Gary Telles). And some are more generalized, like the marketing executives who chirp, “Let’s do lunch!” in their unflappable cluelessness as you dispatch them. Either way, the social satire here has the sharp edge that was missing from the Spellcasting games:

Junk Bond Amoeba: Environmental toxins have produced these one-celled creatures, twelve feet across, bent on engulfing food morsels and defenseless companies. Beware, for during combat they can divide by mitosis, doubling their number!

Espevangelist: Similar to televangelists of the 20th and 21st centuries, except that espevangelists require no broadcasting equipment to transmit their programming, since they can project their thoughts and words directly into the minds of those around them. In addition to the damage they can thus inflict, espevangelists have been known to separate weak-willed parties from their funds. They are even more dangerous if they FUNDRAISE.

By way of attacking this last-mentioned reprobate, you “reveal details about his affair with an altar boy,” and “all the tears in the world fail to save him.” And all the aging gamers said: Meretzky Is Back.

Transistor Jowl leaves the scene of the crime.

Unfortunately, Superhero League of Hoboken‘s course after its release was markedly different from that of Band on the Run. The game got a lot of support from the all-important Computer Gaming World magazine, including an extended preview and a very positive review just a couple of issues later that proclaimed it “the first true comedy CRPG ever”; this wasn’t strictly correct, but was truthy enough for the American market at least. And yet it sold miserably from the get-go, for reasons which Legend couldn’t quite divine. Legend was no Sierra or Electronic Arts; they averaged just two game releases per year, and the failure of one of them could be an existential threat to the whole company.

But they got lucky. Just after Hoboken‘s release, the book-publishing titan Random House made a major investment in Legend; they were eager to make a play in the new world of CD-ROM, and, having been impressed by Legend’s earlier book adaptations, saw a trans-media marketing opportunity for their existing print authors and franchises. This event took some of the sting from Hoboken‘s failure. Random House’s marketing consultants soon joined in to try to solve the puzzle of the game’s poor performance, informing Legend that the central issue in their opinion was that the cover art was just too “busy” to stand out on store shelves. This verdict was received with some discomfort at Legend; the cover in question had been the work of Peggy Oriani, Bob Bates’s wife. Nevertheless, they dutifully went with a new, Random House-approved illustration for the CD-ROM release, splashed with excerpts from the many glowing reviews the game had received. It didn’t help; sales remained terrible.

Steve Meretzky would later blame the game’s failure on its long production time, which, so he claimed, made it look like a musty oldie upon its release. And indeed, it was the last Legend game to use only VGA rather than higher resolution SVGA graphics. Still, and while the difference in sharpness between this game’s graphics and Legend’s next game Death Gate is pronounced, Hoboken really doesn’t look unusually bad among a random selection of other games from its year; there were still plenty of vanilla VGA games being released in 1994 and even well into 1995 as software gradually evolved to match the latest hardware. The real problem was likely that of an industry that was swiftly hardening into ever more rigid genres, each of which came complete with its own set of fixed expectations. An adventure game with hit points and fighting? A CRPG with no dungeons or dragons, hurling social satire in lieu of magic spells? Superhero League of Hoboken just didn’t fit anywhere. As if all that wasn’t bad enough, unlicensed superhero games of any stripe have historically struggled for market share; it seems that when gamers strap on their (virtual) spandex suits, they want them to be those of the heroes they already know and love, not a bunch of unknown weirdos like the ones found here.

A few months after the release of the CD-ROM version, Legend received a cease-and-desist letter out of the blue from Marvel Comics. It seemed that Marvel and DC Comics were the proud owners of a joint trademark on the name of “superhero” when used as part of the title of a publication. (This sounds to my uneducated mind like a classic example of an illegal corporate trust, but I’m no lawyer…) While there was cause to question whether “publications” in this sense even encompassed computer games at all, it hardly seemed a battle worth fighting given the game’s sales figures. Already exhausted from flogging this dead horse, Legend worked out a settlement with Marvel whereby they were allowed to continue to sell those copies still in inventory but promised not to manufacture any more. In the end, Superhero League of Hoboken became the least successful Legend game ever, with total sales well short of 10,000 copies — a dispiriting fate for a game that deserved much, much better.

That fate makes Hoboken a specimen of a gaming species that’s rarer than you might expect: the genuine unheralded classic. The fact is that most great games in the annals of the field have gotten their due, if not always in their own time then in ours, when digital distribution has allowed so many of us to revisit and reevaluate the works of gaming’s past. Yet Superhero League of Hoboken has continued to fly under the radar, despite its wealth of good qualities. Its sharp-edged humor never becomes an excuse for neglecting the fundamentals of good design, as sometimes tends to happen with forthrightly comedic games. It’s well-nigh perfectly balanced and perfectly paced. Throughout its considerable but not overwhelming length, its fights and puzzles alike remain challenging enough to be interesting but never so hard that they become frustrating and take away from its sense of fast-paced fun. And then it ends, pretty much exactly when you feel like you’re ready for it to do so. A lot of designers of more hardcore CRPGs in particular could learn from this silly game’s example of never exhausting its player and refusing to outstay its welcome. The last great narrative-oriented game of Steve Meretzky’s career, Superhero League of Hoboken is also the one most ripe for rediscovery.

(Sources: the books The Beatles Forever by Nicolas Schaffner and Game Design Theory & Practice (Second Edition) by Richard Rouse III; Computer Gaming World of August 1994 and October 1994; Questbusters 113. Online sources include “The Superhero Trademark FAQ” at CBR.com and “Super Fight Over ‘Superhero’ Trademark” at Klemchuk LLC. I’m also greatly indebted to the indefatigable Jason Scott’s “Infocom Cabinet” of vintage documents from Steve Meretzky’s exhaustive collection. And my huge thanks to Bob Bates and Mike Verdu for their insights about Superhero League of Hoboken and all other things Legend during personal interviews.

Superhero League of Hoboken is available for digital purchase on GOG.com. This is wonderful on one level, but also strange, as it should still be subject to the cease-and-desist agreement which Legend signed with Marvel Comics all those years ago. There is reason to question whether Ziggurat Interactive, the digital publisher currently marketing this game, actually has the right to do so. I leave it for you to decide the ethics of purchasing a convenient installable version of the game versus downloading a CD-ROM image elsewhere and struggling to set it up yourself. Believe me, I wish the situation was more clear-cut.)