Before we begin in earnest today, I’d like to note that if I was writing this series of articles in isolation I would wind up covering a somewhat longer list of games. As it is, though, I’ve already written about what I would consider to be the next two logical suspects in the tradition I’m trying to chronicle here. Like all of the games I’ll be writing about from here on in this series, both are British creations.

First, we have Mike Singleton’s stately 1984 epic The Lords of Midnight. It stands out from the other games in this tradition in that it doesn’t run in real time — technically speaking, it’s actually a strategy-adventure rather than an action-adventure — but it has much in common with them in a thematic sense. Singleton too sought to explode the restricted possibility space of text adventures, refusing to let his expectations be tempered by the limited hardware at his disposal. Working on a 48 K Sinclair Spectrum equipped only with a cassette drive, he built his world as a 64 X 64 square “game board,” filled with multifarious terrain over which you can freely roam. You can look in any direction from any location in the world, seeing a dynamically generated picture of what lies there. Said picture can include friends, enemies, and neutral parties; the world contains dozens of other, computer-controlled actors moving about in pursuit of their own agendas. Despite its turn-based play and its stepped movement, The Lords of Midnight manages to achieve much the same sense of boundless freedom and emergent possibility that mark the best of the purer breed of British action-adventures. It was enormously popular, a perennial on the Spectrum for years, and its influence can be felt on most of the later games you’ll soon be reading about.

Then we have the action-adventures of the legendary development house Ultimate Play the Game. It was through Ultimate, who had connections to the wider international culture of videogames that almost all of their British peers lacked, that the innovations of Warren Robinett’s Adventure first reached Britain. Beginning with Atic Atac in 1984, their first game of the type, Ultimate’s action-adventures thus became the prerequisites for all of the British action-adventures that would follow. Later in 1984, they debuted Knight Lore, the first action-adventure to present its world from an isometric perspective, thus adding the third dimension of depth which Adventure had lacked. It would go on to become arguably the most influential Spectrum game of all time; in its wake, isometric games went from unheard of to absolutely everywhere in Britain in bare months. And then, barely a year on from those landmark games, Ultimate was gone, clearing the way for those who would build on their legacy.

So, have a look at my earlier articles on the aforementioned two topics if you feel the need to, and then let’s continue on to some other living worlds of action and adventure.

Mercenary: Escape from Targ (1985)

British game programmers of the 1980s had an insatiable appetite for vastness, driving them to find ways of making kilobytes of memory seem like megabytes. The canonical example of their peculiar form of programming genius is Ian Bell and David Braben’s 1984 game Elite, which packed a universe of eight galaxies and thousands of star systems into a BBC Micro’s 32 K of memory. Yet, extraordinary as Elite is, Paul Woakes’s 1985 game Mercenary: Escape from Targ deserves mention in the same breath whenever the conversation turns to making a big game using very little. Working within the only slightly more generous confines of a 48 K Atari 8-bit computer, Woakes mapped an entire planet’s surface into memory, creating a virtual space which one can spend hours and hours of real time traversing without ever treading over one’s previous footsteps. Eight years before Doom, on a computer with the merest fraction of the horsepower of the ones used to run that seminal title, Mercenary presented this living world in smooth-scrolling first-person three-dimensional graphics, running in real time. Its presentation was so revolutionary, going far beyond even the 3D graphics of Elite, that people struggled to come up with words to describe it. David Aubrey-Jones, who ported Woakes’s work from the Atari to the Sinclair Spectrum, took a stab at it by saying that Woakes alone among his contemporaries “writes in mathematics”:

The computer is continually evaluating your position, what is visible from your position, and how objects move in relation to you while still remaining in true 3D perspective. This sort of calculation is infinitely more complex than a game where a sprite is plopped down on the screen and just moved left and right.

The process Aubrey-Jones describes would of course come to be known as “3D rendering,” but at the time the necessary vocabulary literally didn’t exist in everyday diction.

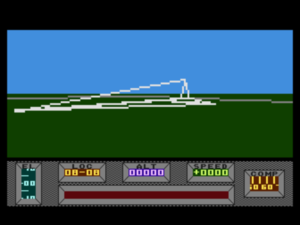

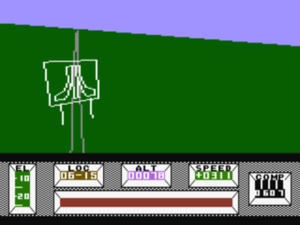

Mercenary may not look like much today, but in 1985 its 3D world was nothing short of revolutionary. Here we’re standing near a flying machine which we can board and fly off in if we like.

Mercenary begins when your spaceship crashes on the planet of Targ. Your overriding goal is, as the game’s subtitle implies, that of simple escape from the planet. Several models of flying machine happen to be spread about the landscape; these you can climb into and use to joyride through the skies. But finding a flying machine capable of carrying you into orbit, where a space station beckons with spaceships bound for other worlds, is easier said than done. Before you can make your escape, you’ll need to explore a huge network of underground corridors that spreads out below the surface of the planet — just in case Woakes’s world wasn’t vast enough for you already. When you go underground, Mercenary takes on more of the characteristics of a conventional adventure game, with locked doors and keys, items to buy and sell, errands to run and corridors to map as best you can. While you’re at it all, you’ll have to reckon with a war that’s raging between the Palyars, the peaceful original inhabitants of Targ, and the Mechanoids, an invading army of robots. You can elect to ally yourself with one side or the other, try to insinuate yourself with both, or charge at all and sundry with guns blazing (although this last is not recommended as a viable long-term strategy).

One of the most extraordinary things about Mercenary is that there are no other embodied characters in its world — the closest it comes are the other flying craft on the surface who can pursue you — yet this world never feels empty. You can communicate with the Palyars and the Mechanoids only from a distance, through your trusty portable computer Benson and the trail of messages and clues left behind by others whom you never see. But somehow it works; the political choices you have to make feel thoroughly real.

The game gives you absolute and thoroughgoing freedom right from the start. You gain control while standing on the surface of Targ next to the ruin of your just-crashed spaceship. In terms of next steps, you have only a hint from Benson to seek out a certain location underground — a long, long way off and underground. At least a flying machine is conveniently close by; you can buy it using most of your meager initial store of cash to get started in your travels. Still, while it seems pretty clear what the game wants you to do at this point, nothing forces you to do it. Instead of taking the flying machine, you can save your money and set off on foot to see what lies beyond the proverbial next hill. Or you can save your money by stealing the flying machine, which will send the police after you in hot pursuit. At that point, you could of course try to escape them through clever flying… or use a well-placed missile to eliminate the threat more quickly. Either way, you’ve just made your first enemies.

Nothing is out of bounds. Most of the appeal of the game, truth be told, has little to do with escaping from Targ: it’s seeing what you can find out there in its world, testing its boundaries, and seeing what you can get away with. More so than Doom, a better point of comparison to Mercenary is actually Grand Theft Auto, and not only because you’ll spend much of your time jumping in and out of different vehicles. Some players might choose to follow the plot, but others couldn’t care less about it — and if you don’t, neither does the game. Another point of comparison — one anchored much closer in time to Mercenary than Grand Theft Auto and, one might even say, closer to it in spirit as well — are the works of that famed virtual-world-builder Richard Garriott. Like his Ultima games, Mercenary was a world before it was a game; the puzzles and plot were the last ingredients to go into the mix. If this can make the mechanics of solving it feel beside the point at times, that seems to be by design. Almost uniquely among games of its era, Mercenary fully supports — even encourages — free-form play, whether you want to go all ultraviolent on it or you want to just stroll around quietly seeing what you can discover. It only emphasizes this spirit of laissez faire to note that it’s impossible to get yourself killed in Mercenary. Even if you power-dive into the ground at mach 5, you’ll always be thrown safely clear of the wreck. Coming in a time when games were infamously cruel, such a forgiving spirit defied every contemporary norm.

The world of Paul Woakes is also like those of Richard Garriott in that it’s a collision of the epic with the personal, its spaces littered with the flotsam and jetsam of its creator’s mind. People and places drawn from his real life abound, along with in-jokes galore. If you blow up a sign advertising Woakes’s previous game, a shoot-em-up called Encounter, you’ll be scolded and trapped on the planet until it’s repaired: “The author won’t let you leave until you fix his advert,” says the game. There’s a flyable block of cheese — a different kind of flying Kraft (groan…). There’s a hapless “Palyar commander’s brother-in-law,” a classic sitcom archetype who keeps getting in your way and getting screwed over in one way or another. (It’s been admitted that he stood in for someone known very well to Woakes in the real world, but in the interest of protecting the innocent and the guilty no more details have ever been allowed to slip out.) There’s a kitchen sink for when you’ve tried everything to solve a certain problem — all but the kitchen sink, that is (bigger groan…).

There are just so many secrets to discover on Targ that have nothing to do with the plot. When you come upon a box of something with the number 12939 printed nonsensically on the side, you might want to look at the letters from the other side, whereupon you’ll find that they spell out Woakes’s caffeine-delivery system of choice: “Pepsi.” (Now it makes sense that they say they need a supply of “12939” to get their work done over in the conference room.) Bruce Jordan, the man who ran Novagen, the little company Woakes founded to sell his games, noted that “this really is the fun part. All of the wacky ideas are Paul’s. He has this weird sense of humor that comes through in the game.”

An Atari logo craving protection (if you’re playing the Atari version) or destruction (if you’re playing the Commodore version). Shooting it in the former version results in being called a traitor; in the latter version, you’re told, “Good show!” And yes, a Commodore logo is found elsewhere in both versions, with the opposite message attached.

Mercenary is littered with secrets and Easter eggs like those I’ve just described, crying out to be cataloged and shared by the game’s many devoted fans. Not least because exploring this world could feel so much like exploring the mind of its creator, a cult of personality sprang up around Woakes which was unusual even by the standards of the British games industry, where the programmers of hit games were often not only known but treated like royalty by their fans. (In the Britain of the 1980s, in other words, Trip Hawkins’s dream of turning “electronic artists” into rock stars actually was to some extent realized.) Woakes, an introverted chap who loathed the spotlight, only magnified his status by refusing every interview and, indeed, rarely appearing to leave his Birmingham home. He thus gained the reputation of a reclusive genius. While Woakes remained in hiding, other programmers gradually ported his game beyond the minority Atari 8-bit platform to machines like the Commodore 64, Sinclair Spectrum, Atari ST, and Commodore Amiga, on all of which it did very well.

In light of all this British success, it’s more than a little amusing to consider the reaction Mercenary engendered when it was imported to the United States. The same game which British reviewers had gushed over as “one of the most exciting releases ever” or, even more extremely, “about the best computer game ever to be written” was roundly panned by American critics, who didn’t seem quite to know what to do with all the freedom they were being offered. “Avoid the unpleasantness of having to Escape from Targ by never getting stuck there in the first place,” wrote one. Another summed the situation up in two words emblazoned on the page in capital letters: “NOT RECOMMENDED.” Seldom have we seen a starker example of the differing expectation of two different gaming cultures. Indeed, many of the other games I’ll be writing about in this series never even got an American release. American publishers knew their customers, and knew that, for whatever reason, there simply wasn’t much of a domestic appetite for games like these.

Woakes followed up the original Mercenary with an expansion pack called The Second City, which added a new complex to explore on the other side of the planet. Then, over the course of the late 1980s and early 1990s, he made a couple of full-fledged standalone sequels, each with expansion packs of its own. Running on more advanced machines than the first game, the sequels replaced the wire-frame graphics of the original with filled solids — and all still well before Doom. Woakes worked for years on each new game at a time when the norm was a handful of months. He thus became the ultimate independent videogame auteur of his era, selling none of his fine wines before their time. Meanwhile his cult of personality analyzed every scant morsel of a clue about him which they could find in his games and awaited his next masterwork with bated breath.

Ever the recluse, Woakes dropped off the radar later in the 1990s, when a changing industry made his way of making games untenable. To my knowledge, he never sat down for a single interview prior to his death in July of 2017. He thus remains even today the subject of considerable speculation and fascination from his aging cult, a sort of ultra-nichey version of J.D. Salinger or Thomas Pynchon.

The best way to get a taste of his eccentric genius today is to visit The Mercenary Site. There you’ll find the inauspiciously named MDDClone, a loving, pixel-perfect re-creation of Mercenary and all of its sequels and expansions for modern Windows and Linux computers.

Fairlight (1985)

Although Fairlight was created by a Swede named Bo Jangeborg, it nevertheless feels like a vital part of the great British action-adventure tradition in that it was hugely influenced by the earlier British hit Knight Lore, was published by a British software house, ran on the British Sinclair Spectrum, and enjoyed by far its greatest success in, you guessed it, Great Britain. But most importantly of all for our purposes, its living world is as amazing for managing to live in just 48 K as anything put together by the greatest British masters of compression. In a telling testament to where his priorities lay, Jangeborg named his game engine the Worldmaker.

His game was released in late 1985, almost simultaneously with Mercenary, and the two titles form a useful study in contrasts. Where Woakes emphasized breadth in his virtual world-building, Jangeborg emphasized depth. The castle in which Fairlight is played consists of just 80 rooms, a far cry from the planet-sized sprawl of Mercenary. In place of the contiguous space of Mercenary, each room in Fairlight is its own discrete place, as in Warren Robinett’s Adventure. And Fairlight replaces the first-person 3D perspective of Mercenary with the third-person isometric view that first took the world of British gaming by storm in Ultimate Play the Game’s Knight Lore.

These points may at first seem to paint a picture of a less ambitious game, but the depth which Fairlight gains in place of Mercenary‘s breadth is in its way every bit as stunning. Jangeborg built for his world an extraordinarily verisimilitudinous physics model, then populated its rooms with objects and creatures to take advantage of it. Well before Richard Garriott would begin pushing in a similar direction in the United States with Ultima V, Jangeborg, with a fraction of the resources at his disposal in terms of both computing potential and human helpers, made a world built of realistic things. Every object in the game has a size, a shape, and a weight which the program accounts for at every step, and the world model allows objects to be beneath, behind, or inside other objects. Throw a dagger against a wall and watch it bounce off and come sliding back toward you on the floor. Push a table over to the wall, set a chair on top, and climb onto a precarious perch to squeeze through that high window. Surround yourself with a barricade of barrels to fend off those soldiers who are attacking from several directions, or leap onto a table and do your best Errol Flynn routine on them. Unlike the turn-based Ultima games, Fairlight does all of this in real time. It’s a heavy task for the little Speccy, so much so that there’s a healthy wait every time you move to a new room, so much so that the whole simulation slows down noticeably for every additional creature other than yourself on the screen. But the incredible thing, of course, is that it works at all.

Due to the limitations of the Spectrum, Fairlight presents itself in monochrome graphics. Far from being a disadvantage, they give the game a certain classy look today in contrast to the garish, clashing colors of so many of its peers.

Almost as impressive as the game’s physics model are the other inhabitants of the castle. As in Robinett’s Adventure, each creature has its own “fears and desires,” and its own way of moving around the world and fighting. Trolls, as you would expect, are big, dumb, and slow, but hit with deadly force if you spend too long in their path. Other enemies are quicker and smarter, capable of lying in wait to ambush you or retreating to join up with comrades elsewhere when the odds start looking unfavorable. And their “desires” really do come into play; if you toss gold on the ground as you’re running away, there’s a good chance the greedy soldiers will stop to pick it up.

Fairlight presents a universe of emergent possibility to replace the static puzzles of standard adventure games. One contemporary reviewer, struggling to articulate differences he could feel but couldn’t quite put a finger on, noted that in other games “each room poses a problem that you’ve got to overcome. Fairlight is one big problem — but you’ll have one helluva time trying to solve it!” There are no single-solution puzzles in Fairlight. Instead there are merely situations — or, if you like, problems — admitting themselves of a multitude of approaches, depending on predilection and circumstance. When you come upon a door guarded by a soldier, you could try to kill him with your sword. Or, you could get him to chase you into the courtyard, then dash back through the door and lock it behind you. You can play the game as a stolid warrior or a slinking thief as it suits you, without ever having to choose a class in some dry character-creation system.

To an only slightly lesser extent than Mercenary, Fairlight encourages open-ended playful play alongside more focused attempts to solve it. (You accomplish the latter, by the way, by rescuing a certain wizard who’s been imprisoned in one of the castle’s towers.) Among the castle’s fiendish inhabitants are soldiers who collapse down into their helmets when they die, then re-spawn from them after a certain amount of time has passed. In the spirit of “I wonder what will happen if,” players started piling the helmets together in a single room, making an informal contest out of seeing how many resurrected soldiers they could pack in thereby. The Worldmaker engine, for what it’s worth, seems to have no hard upper limit on the number of inhabitants allowed in a room, although the game gets extremely slow as the numbers grow. But the biggest problem by the time you have, say, eight soldiers packed into such a small space is just surviving long enough inside the resulting Cuisinart of whirling blades to make it to the door.

Fairlight is the rare game where even the title screen is important. Looking closely at the castle here can give vital clues about the location of potential secret doors leading to unexplored areas.

Played today, Fairlight has some clear-cut issues beyond the slowdowns. The interface can be awkward. It takes time to get a feel for how to line up your movements with the diagonal lines of the isometric display, while picking up and manipulating objects can be annoyingly fiddly, requiring you to be standing just so in relation to them. And for all that Fairlight‘s world is much smaller than that of Mercenary in absolute terms, its castle is still a big place, virtually requiring you to make a map if you’re not to get hopelessly lost inside, not to mention if you hope to find the likely location of secret areas. Yet making an accurate map is no mean feat in itself, what with the isometric view once again confusing the matter and things constantly happening all around you in real time. All of these factors can combine to make Fairlight extremely off-putting when you first pick it up. Still, it is worth exploring, if only for a little while, to gain an appreciation for the major feat of programming talent and sheer imagination that it is. Quite apart from all its other strengths, its physics model alone is a decade ahead of its time.

Like Paul Woakes of Mercenary fame, the auteur behind Fairlight was something of an enigma. Spending most of his time in his native Sweden, Bo Jangeborg seldom gave interviews to the British press even when his game was at the height of its success. In the end, his time as a game programmer proved even shorter than that of Woakes. He had a major falling-out with his publisher, a sketchy outfit known as The Edge,[1]The Edge was run by one Dr. Tim Langdell — he has always insisted his name be prefixed with his title — who has been a vortex of conflict and controversy since at least 1983, when he caused a brouhaha in the young British microcomputer industry by threatening to sue several developers who had used a BASIC compiler made by his company Softek to write commercial software without his permission. Anecdotes about Langdell’s jerky behavior soon became common barroom fodder within the industry, only occasionally surfacing in public. Insider legend has it that one of The Edge’s programmers, who Dr. Langdell demanded create a slapdash X-Men game in a ridiculously short time before his license on the property expired, finally had a meltdown in response to the constant needling. He punched Dr. Langdell in the face before walking out, thus fulfilling the fondest wish of many; the game, needless to say, was never released.

One hilarious bit of snark that did make it out for public consumption was the magazine Amiga Computing‘s review of The Edge’s game Garfield: Winter’s Tail in 1989. It’s told from the perspective of the titular cartoon cat:

Garfield has signed up with The Edge, but notices that Tim Langdell, the boss of the company, doesn’t quite smell right. A first inkling of the horror to come.

Then Garfield notices that there are holes in Tim’s jumper, and that he’s wearing a tatty old hat. Odd, but it gets odder when Tim shows Garfield how the game is progressing some months later.

There’s a scrolling section, a scene in a chocolate factory, and a skating part. But where’s the Garfield, the plump one asks. “Right where we want him,” snarls Tim, six-inch blades flashing across the office, glinting in the moonlight streaming through the window.

Garfield meows in surprise and finds himself catapulted into the game… [cue an extended pan of the game]

That’s it for poor Garfield. His alter ego returns to his captive computerised torso and shivers under the blanket. Garfield can only sit and wait, and hope that some talented individual with the patience of Job can finish the game and rescue him from this nightmare that The Edge created.

The next issue contains a contrite apology, obviously dictated to the magazine’s staff by Dr. Langdell’s lawyers:

In last month’s issue in the review of The Edge’s new game Winter’s Tail some personal remarks were directed at Dr. Tim Langdell. We accept that these remarks were totally uncalled for, and insofar as they might have been read to be a slight on Dr. Langdell’s character or on The Edge’s reasons for licensing the Garfield character, we unreservedly apologize to Dr. Langdell and all at The Edge for these remarks.

Having thus so thoroughly worn out his welcome in Britain that he was being slagged off in everyday reviews of his company’s games, Dr. Langdell moved his operation to the United States in the 1990s, where he occupied himself for many years with threatening anyone in the games industry who tried to use the word “edge” in pretty much any context. He won a hefty settlement from the videogame magazine Edge, but overreached himself by going after the giant Electronic Arts for releasing a game called Mirror’s Edge in 2008. In response to a petition from EA which noted that he wasn’t actually doing anything with them other than threatening lawsuits, a judge invalidated Langdell’s trademarks on “Edge,” “Cutting Edge,” “Gamers Edge,” and “The Edge.” Undaunted, he has apparently moved on to mount fresh legal attacks using other specious trademarks. His membership in the International Game Developers Association was terminated in 2010 due to “lack of integrity” and “unethical behavior.” over two issues. The first was their release of a Commodore 64 port of Fairlight with a bug in it that made the game impossible to complete; this they refused to ever address or even acknowledge, an unconscionable breach of faith with their customers. But The Edge’s relationship with Jangeborg fell apart for good only when they pulled Fairlight II out of his hands before it was complete and released it, full of mysteriously disappearing objects, spontaneously appearing monsters, and rooms that seemed to wander about the castle of their own accord, in order to capitalize on the 1986 Christmas sales season. Jangeborg claims that The Edge forced him to sign a contract authorizing the sequel’s release by withholding payment on royalties due from the first game. After that bitter experience, he never made another game.

Fairlight is unfortunately not so convenient to play today as Mercenary; it must be played using a Spectrum emulator such as Fuse. But the hardy among you who are willing to go through the trouble can find everything you’ll need to play it on an emulator at The World of Spectrum.

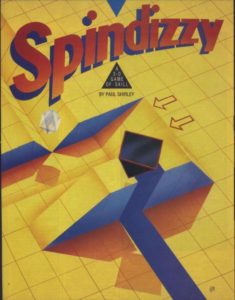

Spindizzy (1986)

One of the biggest international arcade hits of 1984 was a game from Atari called Marble Madness. In it, you control a marble rolling along an obstacle course full of jumps, hairpin turns, and other, evil marbles trying to knock you off the edge of the course. Two years after its arcade debut, Marble Madness came to computers for the first time in the form of an exemplary conversion for the Commodore Amiga from Electronic Arts. It became one of the Amiga’s biggest early showpiece games.

Yet even as the Amiga, with the comparatively huge amount of computing power it had on tap, was being turned to the task of duplicating the straightforward level-based arcade game by American programmers, a British programmer named Paul Shirley was applying some of the mechanics of Marble Madness to something far more innovative and ambitious — and doing it all within the tight constraints of an 8-bit Amstrad CPC home computer at that. Inspired, like all those countless other young British programmers, by the example of Knight Lore, Shirley had already worked up the routines to display a network of rooms from an isometric viewpoint when he first saw Marble Madness in a local arcade. This, he says, gave him the “rollaround idea,” leading him to design an unlikely mashup of Marble Madness and Knight Lore, taking the core mechanics of the former and applying them to an open world awaiting free-form exploration — a huge difference from the constrained level progression of the arcade game. “Whereas Marble Madness is a race,” Shirley said, “Spindizzy is more of an adventure.”

For all that adventure games are often seen as the very first narrative-focused computer games, most early adventures are actually more about exploring their architectures of space than they are about plot. When you solve puzzles, your reward is more rooms to explore, and when you reach the last room, you’ve usually either won already or are very close to it. With Spindizzy, Shirley took this notion to its logical extreme by making entering as many “rooms” as possible your one and only goal. You play a “Trainee Assistant Cartographer for Unknown Worlds” assigned to explore the recently discovered Hangworld: a labyrinth hanging suspended in “inter-dimensional space.” If you manage to visit every one of the 386 screens which make up Hangworld, you’ve won. But doing so is a very tall order.

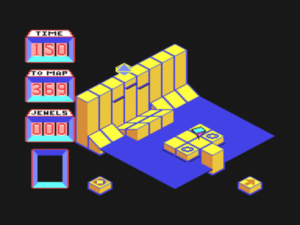

Spindizzy in action. The numbers at the left show seconds of fuel remaining, rooms remaining to explore, and how many fuel jewels have been collected so far. Gerald, your avatar — or rather your avatar’s vehicle — is the inverted pyramid toward the right. Atop the ledge is a fuel jewel. The problem, of course, is figuring out how to get Gerald up there to collect it…

Like so many classic puzzle games, Spindizzy builds seemingly endless variation out of a very limited supply of parts. This puzzle game, however, adds all the pressure of an action game to the mix. Getting from one screen to another in your little marble of a spacecraft, who in the game’s quirky fashion is unaccountably known as Gerald, requires reflexes and coordination as well as puzzle-solving skills. Tight squeezes and jumps abound, as do pressure plates which cause effects elsewhere that you’ll need to discover for yourself. The physics model is almost as impressive as that of Fairlight; momentum and conservation of energy are critical. Gerald can actually be transformed at will into any of three separate shapes — a ball, a tetrahedron, and a gyroscope — each with its own handling characteristics. He also comes equipped with a turbo unit, but it must be used sparingly, as it consumes fuel at a prodigious rate. Ditto falling off one of the sides of the maze due to a misjudged corner or an overshot jump. A timer counts down the seconds of fuel remaining in Gerald before he goes dead and you lose the game; you begin with only enough to last 107 seconds of normally aspirated play. You can pick up more fuel by passing over energy jewels, but there never seem to be as many of them as you need. And no, there is no save function.

It all makes of Spindizzy a brutally difficult game, one requiring anyone who hopes to see its victory screen to play it over and over again, hopefully getting just a little further each time. The number of players who have managed to complete it — who have even come anywhere close to finishing it — must be vanishingly small. Yet the game has a way of drawing players who swear it off in frustration back again the very next day, determined despite themselves to pick up where they left off and try to see a few more rooms. Universally judged by reviewers to be as praise-worthy as it was confounding, it was a big hit in 1986.

Cruel though it otherwise is, Spindizzy does do you the favor of providing a map which you can reference at any time by pressing the “M” key. As you can see, Hangworld is a big, big place.

Thankfully for the less hardcore among us, Paul Shirley did return to the concept once more. After a couple of less notable games, he made a pseudo-sequel called Spindizzy Worlds for the Atari ST and Amiga in 1990. It’s much larger but in many ways more forgiving than its predecessor: more hints are on offer as to where you should be going next and what you should be doing there, and the game is saved when you finish off one of its many component “worlds.” The first round of reviews were superlative; the sequel seemed to be shaping up to be at least as big a hit as the original. But Spindizzy Worlds was released on the Activision label in Britain just as Mediagenic, the label’s American parent company, was collapsing. It appeared in British shops in only tiny quantities, then promptly vanished forever, thus becoming one of the great should-have-been-a-contenders of gaming history.

Spindizzy Worlds on the Amiga looks snazzier than its predecessor, and is an even better game to boot.

Shirley too then vanished from the games industry. He claims he was never consulted about nor paid for a Super Nintendo version of Spindizzy Worlds which the resurrected Activision released in 1993. Asked years later in a rare interview what he would do to improve the industry, his reply made it clear that his bitterness persisted: “Shoot the crooks and incompetents running most of it.”

As Spindizzy Worlds proved to the few who got a chance to play it in its day, there’s still a lot of life in the Spindizzy concept. Add save points and some other measures to make it more reasonable, and I can imagine it doing well today. Various projects have been launched to remake it, but to my knowledge none have yet come to fruition as a complete, playable game. As it stands today, then, your only option is to play it through an emulator. You can download Spindizzy for the Spectrum at World of Spectrum or, even better, Spindizzy Worlds for the Amiga from right here — to play the latter, you may want to invest in the Amiga Forever emulator package — and have at it.

(Sources: Amstrad Action of May 1987 and October 1993; A.N.A.L.O.G. of January 1987; Atari ST User of February 1987; Commodore User of May 1988; Crash of September 1985, May 1986, June 1986, and September 1987; Midnite Software Gazette 40; New Computer Express of July 29 1989; Page 6 of March 1986 and January 1987; Popular Computing Weekly of March 3 1983, March 17 1983, May 26 1983, December 26 1985, January 9 1986, and May 22 1986; The Games Machine of October 1987; The One of August 1989, May 1990, November 1990, June 1991 and February 1992; Zzap! of March 1986, June 1986, September 1986, and July 1991; Questbusters of January 1987; Sinclair User of September 1985, October 1986, November 1986, December 1986, and April 1987; Your Spectrum of November 1985; Amiga Computing of November 1989, December 1989, and January 1991; CU Amiga of November 1991; Game Developer of April 2010 and November 2010; Home Computing Weekly of June 21 1983; Amtix of March 1986; Retro Gamer 52. Online sources include Eurogamer’s “Mercenary Retrospective,” Electron Dance‘s “The First Open World,” Sockmonsters‘s “The Making of Mercenary,“ Paul White’s interview of Bo Jangeborg, and Rock Paper Shotgun‘s “Tim Langdell Loses in Future ‘Edge’ Trial,” and Halcyon Days‘s interview of Paul Shirley.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The Edge was run by one Dr. Tim Langdell — he has always insisted his name be prefixed with his title — who has been a vortex of conflict and controversy since at least 1983, when he caused a brouhaha in the young British microcomputer industry by threatening to sue several developers who had used a BASIC compiler made by his company Softek to write commercial software without his permission. Anecdotes about Langdell’s jerky behavior soon became common barroom fodder within the industry, only occasionally surfacing in public. Insider legend has it that one of The Edge’s programmers, who Dr. Langdell demanded create a slapdash X-Men game in a ridiculously short time before his license on the property expired, finally had a meltdown in response to the constant needling. He punched Dr. Langdell in the face before walking out, thus fulfilling the fondest wish of many; the game, needless to say, was never released.

One hilarious bit of snark that did make it out for public consumption was the magazine Amiga Computing‘s review of The Edge’s game Garfield: Winter’s Tail in 1989. It’s told from the perspective of the titular cartoon cat: Garfield has signed up with The Edge, but notices that Tim Langdell, the boss of the company, doesn’t quite smell right. A first inkling of the horror to come. Then Garfield notices that there are holes in Tim’s jumper, and that he’s wearing a tatty old hat. Odd, but it gets odder when Tim shows Garfield how the game is progressing some months later. There’s a scrolling section, a scene in a chocolate factory, and a skating part. But where’s the Garfield, the plump one asks. “Right where we want him,” snarls Tim, six-inch blades flashing across the office, glinting in the moonlight streaming through the window. Garfield meows in surprise and finds himself catapulted into the game… [cue an extended pan of the game] That’s it for poor Garfield. His alter ego returns to his captive computerised torso and shivers under the blanket. Garfield can only sit and wait, and hope that some talented individual with the patience of Job can finish the game and rescue him from this nightmare that The Edge created. The next issue contains a contrite apology, obviously dictated to the magazine’s staff by Dr. Langdell’s lawyers: In last month’s issue in the review of The Edge’s new game Winter’s Tail some personal remarks were directed at Dr. Tim Langdell. We accept that these remarks were totally uncalled for, and insofar as they might have been read to be a slight on Dr. Langdell’s character or on The Edge’s reasons for licensing the Garfield character, we unreservedly apologize to Dr. Langdell and all at The Edge for these remarks. Having thus so thoroughly worn out his welcome in Britain that he was being slagged off in everyday reviews of his company’s games, Dr. Langdell moved his operation to the United States in the 1990s, where he occupied himself for many years with threatening anyone in the games industry who tried to use the word “edge” in pretty much any context. He won a hefty settlement from the videogame magazine Edge, but overreached himself by going after the giant Electronic Arts for releasing a game called Mirror’s Edge in 2008. In response to a petition from EA which noted that he wasn’t actually doing anything with them other than threatening lawsuits, a judge invalidated Langdell’s trademarks on “Edge,” “Cutting Edge,” “Gamers Edge,” and “The Edge.” Undaunted, he has apparently moved on to mount fresh legal attacks using other specious trademarks. His membership in the International Game Developers Association was terminated in 2010 due to “lack of integrity” and “unethical behavior.” |

|---|