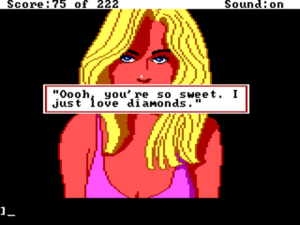

Larry’s dream girl, who also features on the Leisure Suit Larry box cover, pays homage to Softporn‘s famous cover art.

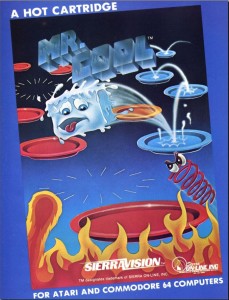

Ken Williams had always loved Softporn, right from the day he first discovered it and spent three or four hours obsessively playing it. It became on that day the only adventure game, ever, that he sat down and solved all by himself, just like any ordinary fan. Still, while Softporn turned into a huge early hit for Sierra and helped to garner for the company some of its first national attention via an article in Time magazine, its shelf life was relatively short. Right from the beginning its text-only presentation — it was the only text-only game of any sort ever published by Sierra — placed it decidedly at odds with the rest of the company’s catalog. And not only was it an all-text adventure, but it wasn’t even a very sophisticated all-text adventure at that; it was a painfully slow BASIC-driven experience with a two-word parser. And then there was that cover art, with Roberta Williams, who by 1983 had become the wholesome centerpiece of much of Sierra’s public relations, posing topless in a jacuzzi with two other women and a mustached waiter straight out of Porn Chic Central Casting. Small wonder that Softporn was quietly dropped from the catalog that year. With Sierra now pursuing deals with the likes of Jim Henson and Disney, those days seemed like ancient history, the cover art a dispatch from another life.

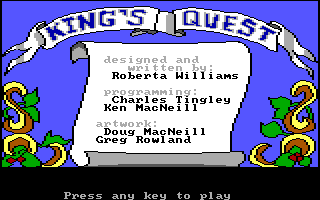

By late 1986, with Sierra now known chiefly for Roberta’s family-friendly King’s Quest adventures, those wild early days seemed more ancient than ever. And yet Ken still couldn’t quite manage to forget Chuck Benton’s ribald game, so different in style and subject matter not only from any other adventure game in 1981 but also from anything available now, more than five years later. Always eager to see computer games as mainstream, mass-market entertainment, he was naturally eager to pursue any fresh fictional genre that could help push them there. The sex comedy had long been an established commercial winner in the cinemas, accepted or at least tolerated by all but the most morally conservative segments of society. Why not in the realm of games? If he needed further encouragement, it came about this time in the form of Infocom’s Leather Goddesses of Phobos, which rode Steve Meretzky’s naughty wit and more sexual innuendo than actual sex to near the top of the sales charts that 1986 Christmas season, becoming despite its increasingly passé text-only format Infocom’s last major hit and last title to make a real impact on the industry at large. Clearly sex sold in the realm of computer games just as well as it did in that of any other form of media. What, then, might happen if Ken gave the world a sexy game with pictures?

The New England-born Chuck Benton, after hanging around Sierra for a couple of years working on various lower-profile programming projects, had long since concluded that neither California nor the games industry was for him in the long term, fleeing back East to start a technology company of his own. He wasn’t interested in revisiting Softporn, but, as long as he was properly credited and remunerated for his original work, he wasn’t averse to someone else at Sierra doing so. Ken therefore invited Al Lowe to lunch, to ask if he’d like to have a go.

Judged on the basis of his work history at Sierra alone, Al Lowe would seem the strangest of choices to assign to a sex farce. Until now, he had been Sierra’s children’s software specialist, who had spent the last couple of years making games with Disney — about as far away from Softporn as one could get and still be working in the same industry. If you actually knew Al, however, it all made more sense. His reputation as a very funny guy preceded him everywhere; he was the sort of natural comedian who not only loved a good joke but knew how to deliver it in such a way that you almost couldn’t help but laugh. Nor was he bashful in the least if said joke was a little — or a lot — off-color.

Yet Al remained uncertain. Funny guy or not, he’d never tried to write a single line of comedy in his life. Like just about everyone else with an Apple II in 1981, he had played the original Softporn, but only vaguely recalled it. He asked Ken to give him a week or so to review the original and decide if he was really willing to spend months remaking it in Sierra’s AGI graphic-adventuring engine.

His first words to Ken at their next meeting, as repeated about a million times in interviews given by Al himself, have passed into industry legend: “This game is so out of touch it should be wearing a leisure suit!” Pop culture moves fast sometimes. Chuck Benton had written his tale of nightlife in the disco era at the frayed end of said era, approximately five minutes before disco became one of the greatest “what the hell were we thinking?” laughingstocks in the history of pop music. Thus just five years later, with the era of synthpop and hair metal now in full swing, Softporn did indeed seem as out of date culturally as it did technologically. Al would take on the project, he said, only if he could be allowed to not just remake Softporn but to make fun of it. Luckily, the line he’d used to introduce his argument had gotten a big laugh from Ken. Ken said sure, go for it.

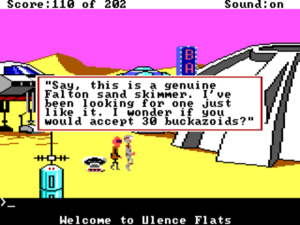

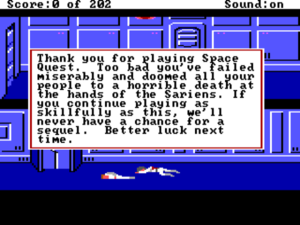

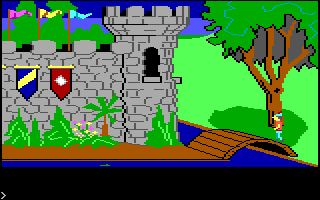

But now, having secured Ken’s permission to make fun of Softporn rather than merely remaking it, Al found himself in a tricky situation for any would-be satirist: his target, while it may have sold as many as 50,000 copies back in the day, was hardly likely to be known to everyone who might happen to pick up his new game. The vast majority of the many more people who would (hopefully) play his parody would have bought their computers after the original went out of print. And whatever else happened, the new game would need a new name; even Ken Williams wasn’t going to dare to release a game called Softporn in 1987. Al decided that what he really needed was a central character for both he and the player to abuse, one who would personify all of the outmoded disco-era thinking of this old Softporn game that most players wouldn’t know the first thing about. Indeed, amongst his litany of complaints about Softporn was the lack of any such central character; that game refers to its protagonist, Scott Adams-style, as simply your “puppet.” This was hardly unusual amongst adventure games of the 1980s; games that had you explicitly playing a character who clearly wasn’t you were very much the exception, and not always well-received exceptions at that. Still, Sierra’s own recent graphic adventures had always elected to offer a definite protagonist: King’s Quest‘s King Graham, Space Quest‘s stalwart space janitor Roger Wilco.

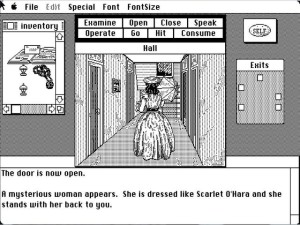

Batting around ideas with Sierra staffers, Al kept coming back to one employee that no one there liked all that much, a smarmy traveling sales representative named Gary whose sartorial and musical predilections were a decade out of date but who nevertheless always came back from his sales trips full of stories about his latest sexual conquests. Borrowing from the first joke Al had ever made in connection with the project, for a time the new game was to be called Leisure Suit Gary. John Williams had a sister-in-law with a reputation for hard partying that had long since garnered her the nickname of the “Lounge Lizard.” Al liked that so much that he was soon calling his game Leisure Suit Gary in the Land of the Lounge Lizards. Seeing the alliterative potential of a change of Gary’s name, and realizing that it wouldn’t be a bad idea to put a little distance between the game’s protagonist and his inspiration, he finally settled on Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards. Larry Laffer would be a “totally mild and lazy guy,” an unlucky-in-love 38-year-old — not quite the original 40-year-old virgin, but close — who’s decided to ditch his Air Supply and Barry Manilow records and head to Lost Wages (replacing Softporn‘s Lost Vagueness) to cover himself from head to toe in fake gold, cheap aftershave, and acres of white polyester, all with the goal of finally getting himself laid. Whether Al Lowe was really still making fun of Softporn by the time he’d found such a personification for that game’s out-of-dateness is more interesting philosophically than practically.

Despite Ken’s enthusiasm, this was a very risky project for a Sierra that was still not all that far removed from a near-death experience. To keep nervous investors at bay it was necessary to make Leisure Suit Larry almost a skunk-works project. Al Lowe’s contract reflected that. He had done the Disney stuff under straightforward work-for-hire arrangements, money paid for services rendered and projects completed. For Leisure Suit Larry, however, Ken convinced him to forgo upfront payment in favor of a very generous royalty on each copy actually sold, thus pacifying his restless investors by shifting virtually the entire risk to Al himself. The game would be written, designed, and programmed by Al alone using Sierra’s standard in-house tools. The only additional staffer assigned to the project was artist Mark Crowe, who had just finished illustrating and co-designing Space Quest, and even he largely worked on it over nights and weekends, devoting his regular working hours to more reputable projects. Al took a huge risk on Leisure Suit Larry, and he would be amply rewarded; in the end the royalties he would garner from the first Leisure Suit Larry and its many sequels would leave him set for life financially. At the time, though, it was all very uncertain. This was unknown territory in more ways than one.

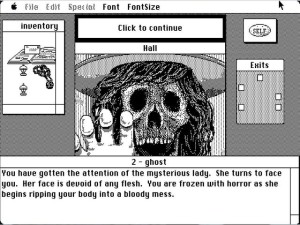

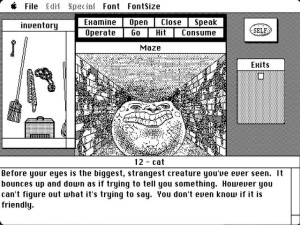

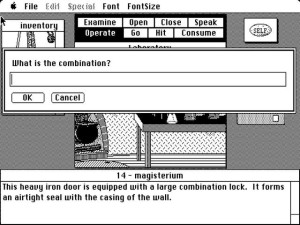

If we address the game that Al and Mark delivered for publication in June of 1987 purely as a piece of adventure-game design, it’s worthy of superlative praise in comparison to any other adventure to come out of Sierra to date, manifesting to any serious degree only a couple of my recent list of “sins”: there is another annoying gambling minigame that can once again only be beat through constant saving and restoring, and, this being a Sierra game, there are one or two unforeshadowed sudden deaths. There’s also one puzzle that doesn’t quite make practical sense (highlight to read: how can you get out your pocketknife to cut the rope when you’re naked and both hands and feet are strapped to the bed?), but even there it’s clear enough what you need to do that it doesn’t matter as much as it might.

Otherwise, Leisure Suit Larry is downright progressive. The places where you can screw up without realizing it are relatively few and usually reveal themselves (sorry!) in fairly short order. The puzzles make sense and are fun to solve and are sometimes even optional in the interest of keeping you moving through the game, while the meta-puzzle that is the narrative sequence of the game as a whole is very satisfying to work out. There is a time limit — Larry has just the one night to score — but it’s generous enough that, what with the occasional saving and restoring you’ll be doing as you sort things out, it’s unlikely to become one of your major problems. Al Lowe bent over backward to address the typical AGI-engine pitfalls that stem from the disconnect between the textual parser and the graphical worldview. Simply typing “look around” in each new location gives you an overview of everything of note in the area and, just as importantly, what to call everything when referring to it through the parser. He also tried to make the anemic parser as usable as possible by gleaning your meaning from the most abstract possible constructions. Simply trying to “use” some applicable item in the general vicinity of a puzzle is usually good enough. Not all of this is exactly elegant (what’s the real advantage of a graphic adventure if I have to constantly type “look around” and read room descriptions?), but it’s a vast improvement over Sierra’s previous games and about the most you could ask of him given that the problems he was trying to address are largely fundamental to the engine itself.

There are a couple of obvious reasons for the huge leap Leisure Suit Larry represents in comparison to Sierra’s previous efforts. The first is that, eager as Al Lowe has often been to dismiss Softporn, Leisure Suit Larry truly is a remake of that game in the sense that, while the character of Larry himself and all of the writing are new, the puzzly spine of the design is all but unchanged. That’s significant because Softporn was itself an unusually friendly and fair game for its day, easily the most solvable adventure Sierra released before Leisure Suit Larry.

The other reason for Leisure Suit Larry‘s success as a game design is that it, very much at Al Lowe’s prompting and hugely to his credit, became the first Sierra adventure ever to go through a proper beta test. Al:

Since the game wasn’t too big, I got it done in about three months. But this was the first non-children’s game I had written, so I was scared to death it would be “dumb” and not understand everything a player could type in.

So I convinced Ken we should try something new: beta-testing. He posted an announcement on CompuServe’s Gamers Forum asking anyone interested in beta-testing a new game to e-mail him a 100-word essay on “why I should get a free game.” It worked. We got scores of replies and ended up with a dozen great beta testers.

To track all the “you can’t do that here” errors (which is what the game says when it doesn’t have a clue what in the hell you typed!), I wrote a special piece of code. Instead of just saying that phrase, it wrote a line to a file on the player’s game floppy. (Hard disks were few and far between back then.) That line told me the scene number, location, the phrase typed, and many other details about the state of the game at that time. I compiled all those files, sorted them scene by scene, and added literally hundreds of responses to the game.

Those testers came up with some great inputs, showing where and when they were frustrated. And because of them, the game makes you think it understands much more than most games of that period.

Absurd as it is that beta testing should represent “something new” to Sierra as late as 1987, it’s difficult to overstate how much better it made the finished game. If you want to know how important actual player feedback is to an adventure design, just play Space Quest or any of the earlier AGI games and then play this one.

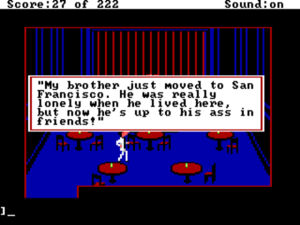

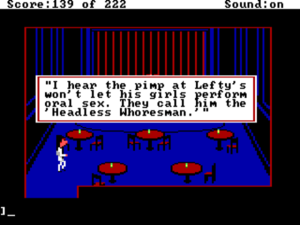

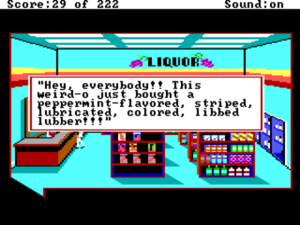

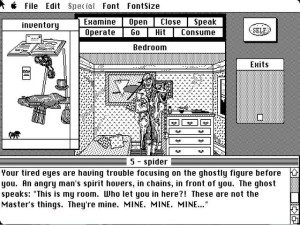

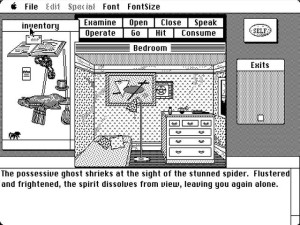

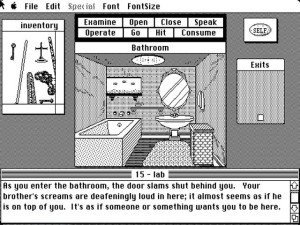

That said, it seems safe to say that very few people bought Leisure Suit Larry to find out whether Sierra’s design craft was improving. The question most of them were asking is the same as the one that may be on the lips right now of those of you who’ve never played the game: just how dirty is it? Al Lowe and others from the good old days at Sierra have tended to downplay the sex and promote the comedy in recent interviews, claiming that even the box copy really promised much more than the game delivered. Having just played through the game again, I have to say that it’s actually raunchier than their statements might imply, if nowhere near as raunchy as might have been wished by the many teenage boys who played it furtively back in the day, hoping it would help them to get off. No, Leisure Suit Larry is nowhere close to pornography, but it certainly pushes the envelope much further than its most obvious contemporary point of comparison, Infocom’s Leather Goddesses of Phobos. While that game was largely a standard save-the-world text adventure with a narrative voice that was inordinately fond of innuendo and the occasional fade-quickly-to-black sexual interlude, Leisure Suit Larry is all about the practical mechanics, if you will, of scoring. Taken in the context of its time, it’s pretty shocking, offering heaps of stuff that hadn’t been seen before in a game from a reputable publisher, or at least not since one called Softporn: blow-up dolls, hookers, pimps, Spanish Fly, condoms, venereal disease, dirty movies, dirty jokes, S&M. A strategically placed “Censored!” stamp appears when Larry actually gets his groove on, and there’s no real nudity other than a tiny pixelated Larry at times and an equally tiny if anatomically correct blow-up doll, but if Leisure Suit Larry had gone to Hollywood in 1987 it would definitely have been R-rated. It’s admittedly shocking not so much for its content in isolation as because its content is in a game, and games just didn’t include that sort of thing in the 1980s. Nevertheless, shocking it is if you’ve been living in the G-rated world of its contemporaries for a long time like your humble Antiquarian here.

It’s a bit hard (sorry!) to see Leisure Suit Larry as a paragon of feminism, even if some of the feminist critiques that have been levied against it over the years are themselves rather overblown.

Leisure Suit Larry was criticized as sexist in a number of the reviews that appeared immediately after its release. “The game contributes nothing to enlightened male attitudes toward women,” wrote MacWorld, while Amazing Computing opined that “many women will probably be incensed.” In the years since it’s only continued to be a lightning rod for feminist critiques of videogames. After all, how could this game whose whole objective is to help Larry score with some random chick or other not objectify and demean women? Al Lowe has long responded that, far from demeaning women, Leisure Suit Larry is itself actually a feminist work in that it’s Larry who’s the bumbling lust-addled idiot, while “the women were always smarter, better read, more knowledgeable, and hipper.”

Well, I can’t quite get behind either point of view. The women — the ones in this first installment of the series anyway — are hardly paragons of independence and empowerment. We’ve got a low-rent hooker who’s never even given a name; a gold digger who demands diamonds, wine, and chocolate before she’ll put out; a buxom secretary in single-minded pursuit of some Spanish Fly to share with her boyfriend; a rich girl who apparently spends her evenings sitting naked in her penthouse jacuzzi just waiting for the next stud to come along. The game’s saving grace, such as it is, is that Larry and all of the men are equally pathetic, equally shallow, and equally stupid. Leisure Suit Larry is thus more accurately accused of misanthropy than misogyny. To what extent that’s an improvement must be in the eye of the beholder.

The most offensive moment in the game actually has nothing to do with sexism or even plain old sex, but is a blatant example of another nasty “-ism.” There’s a convenience store with a turbaned Indian or Middle Easterner behind the counter, a guy to whom even Larry is allowed to feel superior.

This guy, who can sell you a condom amongst other things, has the “Engrish” problem of not being able to pronounce (or apparently write) his Rs: “There is a magazine rack near the front door, with a sign reading ‘This no library — no leeding.'”

I feel like making fun of another person for his accent has got to be amongst the lowest and cruelest forms of “humor” imaginable. Yet the most shocking thing is this scene’s sheer laziness. It’s not speakers of Indian or Middle Eastern languages who sometimes confuse the English “r” and “l” sounds, it’s speakers of Japanese and other East Asian languages. If you’re going to indulge in broad stereotyping, at least try to get your stereotypes vaguely right according to their own lights. Al Lowe has occasionally noted how he and the others at Sierra were essentially making games for each other. This scene shows that culturally monolithic echo chamber at its worst. When I see a guy like this one behind a counter, I see someone who’s left his home and everything he knows far behind, who’s struggling to learn a new language and make a better life for his family, who’s doing something far bolder and braver than anything that the sheltered nerdy white boys at Sierra who’ve decided it’s appropriate to make fun of him have ever even dreamed of doing. He doesn’t need their grief.

This always makes me laugh for some reason, maybe because it’s one of the relatively few places where Leisure Suit Larry shows a certain subtle empathy.

I think the scene in the convenience store might just help us get to the core of what really bothers me about Leisure Suit Larry‘s humor, to the reason that, while it might make me chuckle here and there, I’ll never consider it great comedy. It’s all about mean-spiritedly making fun of people who are — or who are perceived as — weaker and more pathetic than the people who made the game. Al Lowe is a clever guy and he comes up with some clever gags, but his game is at heart an exercise in bullying, looking down on safe targets from a position of privilege and letting fly. There’s no real warmth and little empathy, no sense of shared understanding between the player and the caricatures going about their business onscreen, and certainly not a trace of the bravery that would be required to go after targets in a position to actually defend themselves. I can’t help but draw a contrast with Knight Orc, a game with a caustic edge even more finely honed than this game’s, but one that was willing to speak truth to power, to knock people down a peg who could actually use a little comeuppance. But most of all I think again of Leather Goddesses, a game I find myself liking even more when I compare it to this one. “Sex is fun!” Leather Goddesses tells us. “Everyone should be having it!” “Look at this loser who can’t manage to just score already!” says Leisure Suit Larry in response.

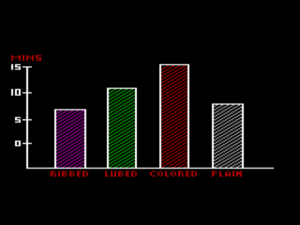

The “boss key” is another innovation Leisure Suit Larry “borrows” from Leather Goddesses. In this case, though, it’s only applicable if you happen to work for a condom manufacturer. Leisure Suit Larry really likes condoms. At least it promotes safe sex. (Just try having sex with the hooker without one…)

Anxious to avoid accusations of selling filth to minors, Sierra came up with the clever idea of a trivia quiz using questions stemming from the 1970s and earlier to make the player “prove” that she really was as old as she said she was. Some of the questions are decidedly obscure, to such an extent that they create quite a challenge to those of us today who are well over the age of eighteen, but, what with almost thirty years having gone by, aren’t quite up to scratch on our Baby Boomer trivia. Thankfully we have a secret weapon in Wikipedia.

Martha Mitchell was

a. a porno star.

b. a famous author.

c. the outspoken wife of an Attorney General.

d. all of the above.

Who starred in Bedtime for Bonzo?

a. Clint Eastwood

b. Fred Astaire

c. Cary Grant

d. Ronald Reagan

Kwi-Chang-Caine became famous by saying

a. “I am not a crook.”

b. “The barren fig tree bears no plumes.”

c. “Hi, sailor. New in town?”

d. “Aaaaaiiiyeeeaagggh!”

As the sheer quantity and variety of questions will attest, the quiz became a huge source of amusement in its own right for Sierra, just about everyone around the office pitching in with a question or two. The questions’ time-capsule quality, the knowledge that these things were once common wisdom amongst people of a certain age, makes them one of the most interesting things about Leisure Suit Larry to an historian like me.

As for the quiz’s ostensible real purpose of keeping the kids out, it must have been moderately but hardly comprehensively effective even in the years before Wikipedia. Gamers in that era were, by necessity, incredibly patient, and there’s very little the average teenage boy won’t do if you promise to reward him with a glimpse of sex. Plenty were willing to try again and again waiting for the same questions to recur, or to scour encyclopedias or libraries for the right answers. At worst, the quiz did allow Sierra to maintain the public position that they’d be horrified — horrified! — if an underage player managed to play their “adult” adventure game, that they were doing everything reasonable to prevent that from happening. Their case was strengthened by Ken Williams’s longstanding policy of not supporting the Commodore 64, the computer with the most active cadre of teenage users. The MS-DOS machines where Sierra focused most of their attention were much more expensive than the likes of Commodore’s little breadbox, and thus their user base tended to skew much older. Still, it’s safe to say that lots of teenage boys evinced a sudden interest in the business computers their parents kept tucked away in their home offices, another sign of the coming Intel/Microsoft hegemony in the home as well as the workplace.

Sierra was in a delicate spot all the way around with Leisure Suit Larry, needing to protect their image as producers of wholesome products for the Radio Shack demographic whilst also getting the word out to those who might be interested in its illicit thrills. There was never any real possibility of being able to sell the game through Radio Shack, despite the close personal relationship Ken Williams had built with their senior software buyer Srini Vasan. Radio Shack’s roots were planted deeply in the soil of Southern Baptism; there was simply no way they were going to put a sex farce on their shelves. Thus Sierra’s task, which primarily fell onto the thin shoulders of their young marketing director John Williams, must be to make the game sell well enough through other outlets to offset the loss of the retailer that accounted for one-third or more of Sierra’s revenues every month, while at the same time not jeopardizing that very cozy relationship upon which they so completely depended.

So, a careful treading was seemingly called for. At the same time, though, John, despite being a grizzled veteran of the software wars, was still a very young man of barely 25. Everybody wants to feel like a rebel once or twice in his life, and John couldn’t resist a bit of crowing about the new ground Sierra was breaking. He greeted Leisure Suit Larry‘s release with a series of three feature articles for Computer Gaming World heralding the “new wave of adult entertainment software” — a wave at the forefront of which would naturally be Sierra. By the time of the third article the first returning tide of outraged reactions — which, one senses, John was expecting and almost welcomed in his rebel heart — had begun to pour in.

Dear Sierra,

I read with regret in your recent newsletter that you intend to go into the porno software business. How any company with your fine products and reputation can make such a poor decision is beyond me. The glorification of loose moral behavior has caused a rise in social disease and divorce and a general decline in the quality of American society. The money you make from this filth comes at a high price.

Dear Sierra,

Please drop that puerile, obviously immature slimeball John Williams into a greasy brown wrapper and drop it in the nearest trash compactor. Please remove my name from your customer list. I don’t need trash, I can get that anywhere.

Dear Mr. Williams,

Recently, I purchased your HomeWord Plus program. I am very happy with it, but I am returning it because I cannot tolerate your behavior. I have read your little “editorial,” where you trumpet the arrival of filth and perversity in computer gaming. I will not do business with any company that would give a job to someone like you.

Just as Infocom had experienced with Leather Goddesses, the reaction in the industry could best be described as “nervous.” Shops and distributors were aware of Leisure Suit Larry‘s huge potential appeal but very timid about openly promoting it for fear of a backlash. Many chains sold it only discreetly, tucking it away quietly on a top shelf. One independent shop took a more definitive stand, sending a demo copy back to Sierra cut in two with a hacksaw. One of the major software charts simply refused to rank it. A customer-support person inside Sierra quit in protest when told she would have to answer questions about it; a newly hired programmer bowed out on his first day when told about it. Ken Williams himself got nervous enough that he ordered all of the jokes about “gay life” to be removed from future versions. If John Williams had deliberately courted controversy, he did indeed receive a modicum of it to enjoy.

The question of to what extent and how quickly that controversy led to sales for Leisure Suit Larry is a more complicated tangle than one might expect. In his many interviews Al Lowe has long told of what a flop Leisure Suit Larry was on its initial release, nothing less than “the worst-selling game in the history of the company.” He attributes much of this initial failure to Sierra’s alleged ambivalence about the game, which led to an unwillingness to promote it and a seeming desire — Ken having presumably thought better of his initial enthusiasm — to just bury it quietly. Only slowly and largely through word of mouth, as Al tells it, did the game build momentum, and it didn’t start doing really big numbers until, depending on the interview, six months to a year after its June 1987 release.

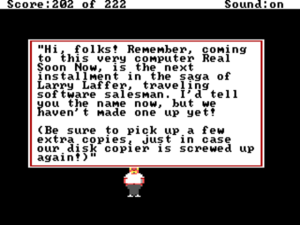

Ken Williams gets a cameo. Note the reference to the original Leisure Suit Gary’s profession as a “traveling software salesman.” This is the only place it’s referred to in the finished game. Woops!

It’s a tidy narrative, but there are a lot of reasons to question it. In the last of his articles for Computer Gaming World, John Williams claims that, far from falling on his face in typical Laffer style out of the starting gates, Larry has been “our second most successful product launch, second only to King’s Quest III.” A list of bestsellers for September and October of 1987 published in Sierra’s newsletter shows an only slightly more mixed picture, with Leisure Suit Larry nestled comfortably behind King’s Quest III and Space Quest, the third best-selling of Sierra’s adventure games. That performance is made more impressive when one remembers that Leisure Suit Larry remained barred from Radio Shack, source of fully one-third of Sierra’s sales. The preponderance of the evidence would seem to indicate that Leisure Suit Larry was that rarest of all beasts: a game that was quite successful on its initial release but also turned into a grower, steadily building its momentum and continuing to sell well for years. Nor is there any evidence that Sierra was really all that scared by Leisure Suit Larry. While certainly aware that they had to avoid throwing it in the face of the likes of Radio Shack and other conservative retailers, they clearly conceived it from the beginning as a series, like all of their other adventure games; the finale explicitly (sorry!) promises a sequel which would indeed come in very short order (sorry!), within a year of the original. Nor were they shy about promoting it in their newsletters, or for that matter shy about writing major feature articles for Computer Gaming World heralding its arrival.

Whatever the precise timing, all are agreed that by the summer of 1988, the game’s one-year anniversary, Leisure Suit Larry had become the biggest game Sierra had ever released that wasn’t a King’s Quest, with the hapless Larry Laffer himself well on his way to becoming the most unlikely of videogame icons. The sequels poured out of Al Lowe for years, some strong, some not so strong, but taking more design risks than you might expect and always serving to maintain Leisure Suit Larry‘s place as Sierra’s second-biggest franchise, the perfect alternative to the family-friendly King’s Quest series. For a time there Hollywood was even seriously interested in doing a Leisure Suit Larry sitcom, going so far as to fly Al Lowe down for some meetings that ultimately never panned out. As so often happens in long-running series, Al took more and more pity on his perpetual victim as the series wore along, steadily filing down his sharper edges and finding unexpected seams of likeability. By the time of Leisure Suit Larry 7 in 1996 the little fellow was starting to become downright lovable, a far cry from the skeezy, crudely drawn weirdo of the first game.

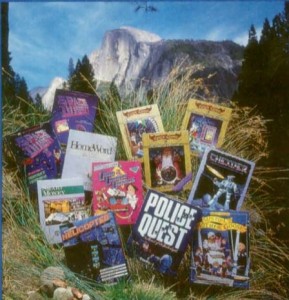

While Leisure Suit Larry itself was a massive success, Ken William’s broader agenda of which it was a part, that of opening up the world of gaming to more diverse sorts of content, had much more mixed results. In the last of his Computer Gaming World articles, John Williams muses about the possibility of a movie-style rating system for games that could create havens for all sorts of new content: G-rated children’s software; PG-rated action games for the teens; R-rated interactive dramas telling realistic, topical tales; even X-rated games constituting the full-on pornography that Leisure Suit Larry, to so many teenagers’ disappointment, wasn’t. Putting their money where their mouths were, Sierra had at the time another game in the pipeline that was “adult” in a different way than Leisure Suit Larry: Police Quest, a gritty crime drama written by a veteran police officer. (Unfortunately, it would prove to suffer from most of the typical Sierra design flaws from which Leisure Suit Larry is so notably free.)

In 1988 Leisure Suit Larry won a Codie Award from the Software Publishers Association for “Best Adventure or Fantasy/Role-Playing Program.” Al Lowe remembers the mood on that night as Ken Williams, president of the SPA, gave the keynote address before an audience that included Robin Williams, Hollywood’s most noted games fan.

He [Ken] said that he thought this was the first of many of these awards to come in the future, and that at some point the Academy Awards would be seen as merely the non-interactive video awards. The real awards would be for interactivity because once you’ve played interactive stories you won’t be content with sitting back and being passive, with watching stories. I thought that was a brilliant statement, and for five or ten years after I thought it was coming true.

This vision for games as a truly mainstream phenomenon like movies, games in a veritable smorgasbord of niches of which at least one or two were guaranteed to appeal to absolutely everyone on the planet, had been with Sierra almost from the beginning and would remain with them until the end. Ken, John, Roberta, and everyone else involved in steering Sierra fully believed that a new era of interactive entertainment was on the horizon. In some senses they would be proved right; games would indeed go mainstream in a big way. But in others they would be proved very, very wrong; games have still not challenged the critical respect or cultural relevancy of Hollywood. When other publishers saw how much money Sierra was making from the franchise and also saw that no one was burning down their offices because of it, Leisure Suit Larry was inevitably copied, sometimes so blatantly as to almost defy belief. Yet there seemed little desire from the industry at large to push beyond the occasional sniggering sex comedy into stories that were “adult” in more subtle ways.

So, then, was Leisure Suit Larry a bold work that tried to break down barriers and redefine the sorts of fictions that games could deal in? Or was it just another example of an industry caught in an eternal adolescence, one unable to address sexuality except through farce or porn? Perhaps it was one or the other or neither; more likely it was both.

(Sources: Computer Gaming World of August/September 1987, October 1987, and January 1988; Amazing Computing of February 1988; Retro Gamer 19; Sierra Newsletter Vol. 1 No. 2. Al Lowe has also written fairly extensively about his most famous creation on his personal site.

Much of this article is also drawn from my personal correspondence with John Williams as well as interviews with Al Lowe conducted by Matt Barton, Top Hats and Champagne, and Erik Nagel. Last but far from least, Ken Gagne also shared with me the full audio of an interview he conducted with Lowe for Juiced.GS magazine. My huge thanks to John and Ken!

The original Leisure Suit Larry is available for purchase from GOG.com in a pack that also includes all of the sequels and even Softporn.)