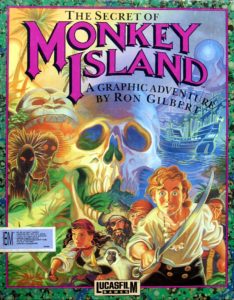

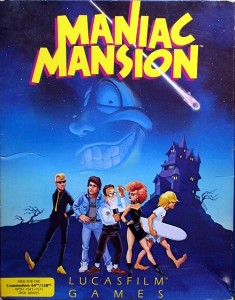

Shortly after completing Maniac Mansion, his first classic graphic adventure, Ron Gilbert started sketching ideas for his next game. “I wanted to do something that felt like fantasy and might kind of tap into what was interesting about fantasy,” he remembers, “but that wasn’t fantasy.” Gilbert loved the Pirates of the Caribbean ride at Disneyland, which took guests through a whole pirate adventure in fifteen minutes. He only wished that he could linger there, could get out of the little boat that carried guests through the attraction and wander amid the scenery. What the need to keep shoveling amusement-park guests through a paid attraction disallowed, a computer game could allow. Thus was the idea for The Secret of Monkey Island born.

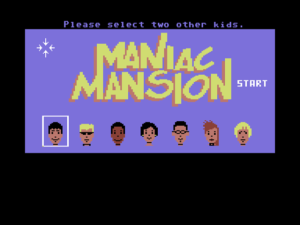

The game casts you in the role of Guybrush Threepwood, a lovable loser who wants to become a pirate. Arriving on Mêlée Island, a den of piratey scum and villainy, he has to complete a set of trials to win the status of Official Pirate. Along the way, he falls in love with the island’s beautiful governor Elaine — her name sets the game up for a gleeful The Graduate homage — and soon has to rescue her from the villain of the story, the evil ghost pirate LeChuck.

The Disneyfied piracy wasn’t hard to do, especially after Gilbert discovered a charming little historical-fantasy novel by Tim Powers called On Stranger Tides. Nor was the goofy humor that was so much his stock in trade as a game designer. What did make things complicated, however, was his desire to create a more playable, forgiving adventure game than even Maniac Mansion had managed to be. Gilbert admits that he was struggling, with no more than the beginnings of a design document or, for that matter, a design philosophy, when a mandate came down from Lucasfilm Games’s parent company’s management: they wanted an adventure game to go with the upcoming film Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Such a mandate was unusual for the privileged little artists’ enclave that still was Lucasfilm Games at this time, but, given the freedom they had so generously been granted for so long, they were hardly in a position to argue about it. Ron Gilbert, Noah Falstein, and David Fox joined forces to grind out the Indiana Jones game, while Monkey Island went on hold for more than six months.

It was just possibly the best thing that could have happened. The delay gave Gilbert time to continue thinking about adventure-game design in the abstract, to continue groping toward that elusive something — or, better said, somethings — that would make his future games different. Hardly a theorist by nature, he nevertheless sat down and wrote out a manifesto of sorts as a way of codifying his opinions, titling it, in inimitable Ron Gilbert fashion, “Why Adventure Games Suck.” This semi-legendary document, probably the most influential ever written on the subject of adventure-game design, was published in the December 1989 issue of The Journal of Computer Game Design (the paper-based adjunct to the Computer Game Developers Conference).

Some of what Gilbert has to say in his manifesto feels a little rambling and esoteric today, while the vast majority of what does feel relevant we’ve already had reasons to discuss on other occasions — what with the general state of adventure-game design in the 1980s, sometimes on all too many other occasions. Still, the document itself and the ideas it contains can only be regarded as hugely important to the evolution of the adventure game.

Consider what the manifesto has to say about the age-old problem of locking the player out of victory without her knowledge.

I forgot to pick it up

Never require a player to pick up an item that is used later in the game if she can’t go back and get it when it is needed. It is very frustrating to learn that a seemingly insignificant object is needed, and the only way to get it is to start over or go back to a saved game. From the player’s point of view, there was no reason for picking it up in the first place. Some designers have actually defended this practice by saying that “adventure-game players know to pick up everything.” This is a cop-out. If the jar of water needs to be used on the spaceship and it can only be found on the planet, create a use for it on the planet that guarantees it will be picked up. If the time between the two uses is long enough, you can be almost guaranteed that the player forgot she even had the object.

The other way around this problem is to give the player hints about what she might need to pick up. If the aliens on the planet suggest that the player find water before returning to the ship, and the player ignores this advice, then failure is her own fault.

In The Secret of Monkey Island and all of the Lucasfilm adventure games that would follow it, Gilbert and his colleagues implemented an extreme remedy to this problem. Rather than admitting a failure to pick up the right object at the right time to be even potentially the player’s “own fault,” they made certain it was always possible to go back and get said item. Locking yourself out of victory, in other words, became literally impossible.

Now consider what the manifesto has to say about arbitrarily killing the player and about another related old bugaboo, requiring knowledge from past lives.

Live and learn

As a rule, adventure games should be able to be played from beginning to end without “dying” or saving the game if the player is very careful and very observant. It is bad design to put puzzles and situations into a game that require a player to die in order to learn what not to do next time. This is not to say that all death situations should be designed out. Danger is inherent in drama, but danger should be survivable if the player is clever.

As an exercise, take one complete path through a story game and then tell it to someone else, as if it were a standard story. If you find places where the main character could not have known a piece of information that was used (the character who learned it died in a previous game), then there is a hole in the plot.

Again, Gilbert and the rest of Lucasfilm would push much further than even the above would imply in their own future designs. Despite the claim that “danger is inherent to drama” — a claim, one has to assume, about which Gilbert must have come to think better — they made it impossible for the player to die, no matter what she did.

Gilbert tells us at the end of his manifesto that he’d like to “get rid of save games” altogether.

If there have to be save games, I would use them only when it was time to quit playing until the next day. Save games should not be a part of game play. This leads to sloppy design. As a challenge, think about how you would design a game differently if there were no save games. If you ever have the pleasure of watching a non-game player playing an adventure game you will notice they treat save games very differently than the experienced user. Some start using it as a defense mechanism only after being slapped in the face by the game a few times, the rest just stop playing.

It’s this idea of designing adventure games as if saves didn’t exist that’s the real key to understanding what made The Secret of Monkey Island and the Lucasfilm adventures which would follow it so different, even so revolutionary. Everything else springs from this one adjustment in perspective. I last played The Secret of Monkey Island nine months or so ago, when my wife and I were on a little holiday in Venice. Each evening, after a long day spent exploring the alleys and canals, we’d retire back to our cozy little hotel and I’d poke at Monkey Island for an hour or two on my laptop before bed. Having played heaps of older adventure games for years prior to getting to Monkey Island — the life of a digital antiquarian sadly doesn’t leave much time for games that aren’t on the syllabus! — I must have experienced it much as its first players did. And I have to say, it’s downright difficult to express how freeing it was to know that I didn’t need to save every ten minutes, didn’t need to stress over the potential of somehow locking myself out of victory with every action. Instead, I could feel free to explore and experiment, knowing the game would take care of me. I don’t say that every game needs to be this way, but I do know that The Secret of Monkey Island is, along with its immediate Lucasfilm predecessor Loom, perhaps the first adventure games I’ve ever played for this blog that felt like natural holiday companions, things to relax into and just enjoy rather than assault with deadly seriousness. And yet The Secret of Monkey Island in particular manages this feat without ever feeling trivial. The game represents a remarkable historical watershed, as of an entire culture of game makers and players waking up and realizing that all the little aggravations they had thought adventure games had to include really didn’t need to be in there at all.

Cheerfully blatant anachronisms like the grog machine and Stan the used-boat salesman are everywhere. Ron Gilbert has mentioned the grog machine as one of his great lessons in “copyrights and trademarks.” Apparently getting it to look enough like a Coke machine to make the joke work but not so much that Lucasfilm was likely to get sued was quite the exercise in triangulation.

Taken apart from its immense importance as a model for future designs at Lucasfilm and elsewhere, The Secret of Monkey Island might initially seem a less than overwhelming package. It exists in very typical adventure-game territory for its era, at first glance dismayingly so. We’ve got yet another sad-sack loser of a protagonist, wandering through a comedy landscape built from pop-culture detritus, anachronisms, and meta-humor. The whole ought to read as lazy as most such efforts. Yet two things save the day, both of which feel intrinsic to the people who wrote the game, Ron Gilbert and his two assistant writers Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman. The first is the marvelously unaffected quality of the humor. The game is consistently, off-handedly funny without ever conspicuously straining to be in the manner of its peers. Where their humor is labored, Monkey Island‘s is effortless. And then there’s the related quality of a certain sweetness about the game. Guybrush Threepwood is the ultimate innocent. He just wants to be a Disney version of a pirate and to rescue and win the hand of the beautiful Elaine; guile is a foreign concept to him. Not only is The Secret of Monkey Island that rarest of beasts, a self-styled comedy adventure that’s genuinely, consistently funny, it’s about as likeable a game as has ever been made. This is a game where when a cannibal asks you how to “get ahead” he means… no, that one’s just too much fun to spoil.

The Secret of Monkey Island isn’t flashy or self-consciously spectacular in the way that so many contemporaneous Sierra adventures strained to be, but it is sophisticated in its aesthetics in a way few other games of its era can match. Still working with 16-color EGA graphics (a 256-color VGA version, from which the screenshots in this article are drawn, was released within a few months of the original), artists Steve Purcell and Mark Ferrari used their limited color palette to good effect to evoke the various moods of the various environments, while Michael Land crafted a gentle reggae-influenced soundtrack to plink away unobtrusively in the background or swell up into the foreground as circumstances dictated. Playing The Secret of Monkey Island really does feel like wandering through a delightful pirate theme park (a quality which the rather infamous ending of the sequel, which we won’t go into further in this article, would take very much to heart).

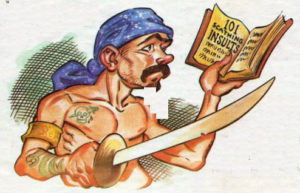

Most of all, The Secret of Monkey Island thrives on its puzzle design. The game’s plot plays out in four chapters, within each of which you have broad discretion to solve puzzles at your own pace and in your own order. (“Give the player options” is another commandment in “Why Adventure Games Suck.”) Its most famous puzzle, “insult sword-fighting,” says much about the game’s personality as a whole: instead of fighting with swords, pirates in this game like to fight via insults. You need to collect these insults and their ripostes as you explore, then apply them just right to win the “sword fight.” (Hey, anything’s better than a sharp sword in the gut, right?) The idea was born as Ron Gilbert was watching old pirate movies of the Errol Flynn stripe, and noticed that the opponents spent as much time verbally as physically assaulting one another. What with a verbal joust being far easier to implement in an adventure game than a sword-fighting engine, it didn’t take him long to run with the idea.

But really the entirety of the puzzle design, top to bottom, is just superb, managing to be funny and clever and occasionally challenging without ever devolving into the random using of each object on each other object. Throughout, attention is paid to you the player’s time and sanity in a way very few games of the era bother to do. For instance, at one point you need to follow another character through the jungle to find a secret location. Most games of the time would happily make you do this over and over, every time you want to return to said location — not least because doing so could serve to boost the length of the game at no expense. The Secret of Monkey Island only makes you do it once, then proceeds to do it for you from then on. “No point in having to solve the same puzzle over and over,” said Gilbert. Amen to that.

The game’s system of nudging you on to the correct solution to many puzzles is subtle to the extent that many players never even notice it’s there — and this, it must be said, again feels like the way it ought to be. At the beginning of the game, you’re expected to fulfill three tasks to prove to the pirates on the island that Guybrush has what it takes to become a pirate as well. As you poke around the island, your challengers actually take note of what you’ve done, and will offer some hints based on your progress if you go back and talk to them. “We want to guide the player subtly through the game,” said Gilbert’s colleague David Fox. “If the game works right, it should know that you’re stuck somewhere and it should give you a little help in a subtle way, so that you can solve the puzzle without feeling like it was solved for you.” In the context of 1990, the year of The Secret of Monkey Island‘s release, this was astonishingly progressive design. “As opposed,” remarked Fox wryly, “to the kind of game where the designer seems to be saying, ‘Aha! I’ve got you this time!’ and you have to spend three hours of gameplay to find some hidden object that you need to solve one puzzle.”

A rare example of a game where every element complements every other element, The Secret of Monkey Island has gone down in history as one of the finest, most justly beloved graphic adventures ever made. And for any aspiring adventure designer, even today, it’s a veritable master class in how to make an adventure game that most definitively doesn’t suck.

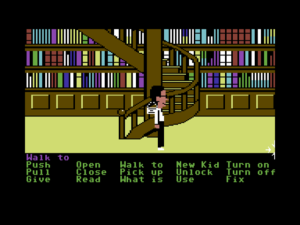

Released in October of 1990 as Lucasfilm’s second adventure of the year, The Secret of Monkey Island shared with its immediate predecessor Loom its pretend-the-player-can’t-save approach to design. Loom, however, had been a bridge too far for many traditionalist adventure gamers. What with its aggressively minimalist interface and portentous setting and story, it felt like an adventure game filtered through the aesthetics of a European avant-garde film. But The Secret of Monkey Island was, to strain the metaphor, all Hollywood. Whatever its innovations, it was also very much a meat-and-potatoes adventure game in the old style, complete with a menu of verbs, a comic tone, lots of object-oriented puzzles to solve, and a length more in keeping with that people had come to expect from a $40 boxed adventure game. It was thus far better equipped to deliver the gospel of “Why Adventure Games Suck” than Loom had been. While Loom had been greeted with critical uncertainty, reviewers fell over themselves to praise The Secret of Monkey Island, which wasted no time in becoming Lucasfilm Games’s biggest hit to date. It marks an enormously important watershed in the history of Lucasfilm’s adventure games in general, the moment when they commercially and creatively came fully into their own. The classic era of Lucasfilm adventures begins in earnest with The Secret of Monkey Island, which would become nothing less than the ideal most of the games that would follow would strive, sometimes perhaps a little too self-consciously, to reach.

Its commercial performance aside, The Secret of Monkey Island‘s enormous importance in the history of the art of adventure-game design in general shouldn’t be neglected. For many designers working at other companies, Ron Gilbert’s no-deaths-and-no-dead-ends approach hit home with the force of revelation. Both Corey Cole, co-designer of the Quest for Glory series for Sierra, and Bob Bates, co-founder of Legend Entertainment, brought up The Secret of Monkey Island unprompted in recent interviews with me as a work that made a huge impression on them. By no means would all designers push as far as Ron Gilbert had in the name of making a more playable adventure game. Corey Cole’s design partner Lori Ann Cole, for example, pronounced herself to be against “capricious” death in adventure games, but insisted that the possibility of death needed to be present to foster “personal involvement” and “an emotional stake” and to elevate the game above “mere amusement” — all of which positions strike me as perfectly reasonable for the very different sort of adventure games she and Corey were making. Still, everyone serious about the art of adventure-game design simply had to reckon with The Secret of Monkey Island, had to decide what its lessons really were and how to apply them. The game’s impact was such that to speak of a pre-Monkey Island and post-Monkey Island era of adventure games wouldn’t be at all out of order.

As the 1990s began, times were beginning to change inside Lucasfilm Games. With the fire hose of cash that had been the Star Wars and Indiana Jones film franchises now ebbing and no new sequels in either blockbuster franchise on the horizon, Lucasfilm in general was concentrating on becoming a more commercially savvy organization. These changes inevitably affected the games division. Just about the instant that The Secret of Monkey Island was hitting store shelves, a major corporate reorganization was in progress at Lucasfilm, which saw the games division given far more resources — their personnel roll grew from about 25 to more than 100 between 1989 and 1991 — but also given much closer supervision. They would now be expected to justify each of their projects to the accountants. This transformation of Lucasfilm Games from sideline to major profit center was by no means viewed as a comprehensively bad thing by everyone working inside the games division — it did after all lead to them finally being let loose on the Star Wars intellectual property, something they’d been wishing for for years — but it would change the character of the place and the games that came from it forever.

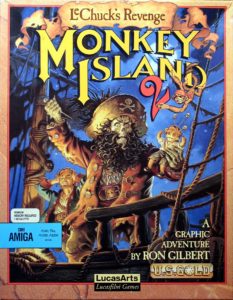

The changes meant that the two sequels to Loom which Brian Moriarty had hoped to make would never be realized; Moriarty was instead sent off to work on a new educational-games initiative. A sequel to the big hit The Secret of Monkey Island, however, became a major priority under the new order, especially as Lucasfilm, now devoting lots of resources to flight simulators and those aforementioned Star Wars games, had no other adventures on their calendar for 1991. Released in December of 1991, Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge didn’t disappoint commercially. Benefiting from the enormous good will accrued by its predecessor, it became another bestseller, and won a number of the game-of-the-year awards that a tardy industry should have been awarding to its predecessor (inertia being the force it is, most of the awards for 1990 had gone to Sierra’s pretty but horribly designed King’s Quest V, which served as its own argument for “why adventure games suck”). Today, the sequel remains almost as beloved as the original among hardcore Lucasfilm fans.

Personally, though, I’m not such a big fan of Monkey Island 2 as I am of its predecessor. Ron Gilbert had spent two and a half years designing, writing, and developing the first Monkey Island, alone or with others. He was given just a year for Monkey Island 2, a game that’s at least 50 percent larger, and I fancy I can see this disparity in the end result. The writing is neither as sharp nor as sweet. For the first time in a Ron Gilbert game, some of the humor is more gross than clever — spitting, with attention to the color and consistency of your loogies, is a major puzzle mechanic — and some of the rest is weirdly mean-spirited. Guybrush Threepwood has been transformed from the gee-whiz innocent of the first game to a bit of a raging asshole, the type of guy who steals a monocle from an innocent character who can’t see a thing without it and locks another guy who didn’t do anything to him inside a coffin. I don’t know to what I should attribute the change in tone — whether to changes going on inside Lucasfilm Games at the time, to changes going on in the personal lives of Ron Gilbert and/or the other members of his writing team, to the pressure of getting a bigger game out in much less time, or simply to happenstance. I know only that it doesn’t sit that well with me.

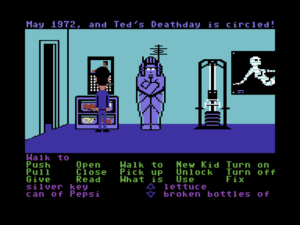

Captured by LeChuck in Monkey Island 2. The game will arbitrarily let you use only one item you’re carrying to effect your escape, and there’s no way to know ahead of time what that item is. Guess what that means you have to do…

In terms of puzzle design, the sequel also marks a big step down from its predecessor. While the no-deaths-and-no-dead-ends approach to design is still present, Monkey Island 2 constantly violates another of the dicta found in Ron Gilbert’s manifesto.

Arbitrary puzzles

Puzzles and their solutions need to make sense. They don’t have to be obvious, just make sense. The best reaction after solving a tough puzzle should be, “Of course, why didn’t I think of that sooner!” The worst, and most often heard after being told the solution, is, “I never would have gotten that!” If the solution can only be reached by trial and error or plain luck, it’s a bad puzzle.

Monkey Island 2 is full of these sorts of, to use Ron Gilbert’s own words, “bad puzzles.” Many solutions are so outlandish that you can stumble upon them only by using every object on every other object. At one point, for instance, you’re carrying a monkey around in your inventory (don’t ask!) when you come upon a closed water valve you need to open. Using the monkey on the valve does the trick because “monkey wrench.” Now, credit where it’s due, there’s some real wit to this. Yet it’s the sort of thing absolutely no player will ever think of on her own, especially given that the game hasn’t heretofore shown any interest in this sort of wordplay. (And that’s without even beginning to consider the problems of localization to other languages than English, which tends to render a puzzle like this into a complete non sequitur.) As you get deeper into the game, there’s more and more of this sort of thing, along with pixel hunts, an infuriating maze, and puzzles that can only be solved by trying to pick up every seemingly immovable item on the screen. Monkey Island 2 at times seems like an experiment in how annoying an adventure game can be without technically violating Lucasfilm’s no-deaths-and-no-dead-ends policy.

Arbitrary puzzles that can be solved only through trial and error would prove to be Lucasfilm’s Achilles heel going forward; too many of the games to come would feature puzzles designed more to create a laugh at how ridiculous they are than to be interesting or satisfying to solve. The end result is to create a feeling in the player of playing the interface rather than participating actively in the game world.

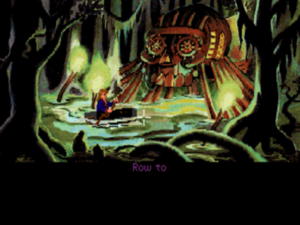

Despite my complaints, by no means was Lucasfilm’s progressive design philosophy completely abandoned for Monkey Island 2. The puzzle you need to solve to get through the swamp is a prime example. After you figure out what object to use as a paddle, the game solves the puzzle for you on each return visit.

Perhaps aware that they had crossed a line in trying to make Monkey Island 2 more difficult than its predecessor, Lucasfilm added a “Lite” mode to the game which scales the complexity of the puzzle structure back dramatically. Unfortunately, most players agree that the Lite mode goes too far in the other direction, removing most of the interest from the game. Taken together, the very presence of the two modes speaks to a design that didn’t quite hit the sweet spot of the first game, and to a design team that at some intuitive level may have realized this.

Shortly after completing Monkey Island 2, Ron Gilbert left Lucasfilm Games, resulting in a long hiatus for Guybrush, Elaine, LeChuck, and company. Given my snail’s pace through history, there will thus likely be an almost equally lengthy hiatus before they’ll grace these pages again. For now, I can only strongly encourage you to make the time to play The Secret of Monkey Island if you haven’t already. It’s as strong a comedy adventure as you’ll ever see, and as historically important an adventure game as any released since Crowther and Woods’s seminal original Adventure. While you can take or leave its sequel as you see fit, The Secret of Monkey Island is one adventure game that everybody really ought to play. It’s just that important. And even better, it’s just that good.

(Sources: the films From Bedrooms to Billions: The Amiga Years and its associated extras; the book Droidmaker: George Lucas and the Digital Revolution by Michael Rubin; A.C.E. of April 1990; The Adventurer of Fall 1990, Spring 1991, and Fall 1991; Computer Gaming World of December 1990, June 1991, October 1991, November 1991, January 1992, May 1992, and November 1992; Retro Gamer 34. Also Ron Gilbert’s blog, The Grumpy Gamer.)