For some of you, Andrew Plotkin will need no introduction. The rest of you ought to know that he’s quite an amazing guy, easily one of the half-dozen most important figures in the history of post-Infocom interactive fiction. By my best reckoning, he’s written an even dozen fully realized, polished text adventures in all, from 1995’s A Change in the Weather, the co-winner of the very first IF Competition, to his 2014 Kickstarter-funded epic Hadean Lands. While he was about it, he made vital technical contributions to interactive fiction as well; perhaps most notably, he invented a new virtual machine called Glulx, which finally allowed games written with the Inform programming language to burst beyond the boundaries of Infocom’s old Z-Machine, while the accompanying Glk input-output library allowed then to make use of graphics, sound, and modern typography. Over the last ten years or so, Andrew — or “Zarf,” as his friends who know him just a little bit better than I do generally call him — has moved into more of an organizing role in the interactive-fiction community, taking steps to place it on a firm footing so that its most important institutions can outlive old-timers like him and me.

Andrew was kind enough to sit down with me recently for a wide-ranging conversation that started with his formative years as an Infocom superfan in the 1980s, went on to encompass some of his seminal games and other contributions of the 1990s and beyond, and wound up in the here and now. I hope you’ll enjoy reading this transcript of our discussion as much as I enjoyed chatting with Andrew screen to screen. He’s refreshingly honest about the sweet and the bitter of being a digital creator working mostly in niche forms.

One final note before we get started: Andrew is currently available for contract or full-time employment. If you have need of an experienced programmer, systems architect, writer, and/or game designer whose body of work speaks for itself, you can contact him through his website.

Perhaps we should start with some very general background. Have you lived in the Boston area your whole life?

No, not at all! I only moved to Boston in 2005.

I was born in 1970 in Syracuse, New York, a place that I don’t remember at all because my family moved to New Jersey when I was about three. We lived there for a couple of years, then my father got a job in the Washington, D.C., area. I went to primary school through high school there.

And when and where did you first encounter interactive fiction?

It must have been around 1979. My father’s company had a “bring your family to work” day. A teletype there was running Adventure. My father plunked me down in front of it and explained what was going on. I thought it was the best thing in the universe. I banged on it for a couple of hours while everybody else was running around the office, although I didn’t get very far.

For the next few months, Dad was playing it at work, illicitly — that was how everybody played it. He would bring home these giant sheets of fan-fold printer paper showing his latest progress. As I recall, I suggested the solution to the troll-bridge puzzle: giving the golden eggs to the troll. That was great, the first adventure-game puzzle I solved.

When did you first get a computer at home?

Around 1980, we got an Apple II Plus. We acquired the first three Scott Adams games and Zork, which was newly available, plus Microsoft’s port of Adventure to the Apple II.

That started my lifelong attachment to Infocom. I played all the games as they came out. I begged my folks to buy them for me. Later, I spent my own money on them.

You played all of the Infocom games upon their first release?

Pretty much, up until I went off to college. I remember that I did not play Plundered Hearts when it came out.

That one was a hard sell for a lot of young men — although it’s a brilliant game.

Yeah. I didn’t play it because I was a seventeen-year-old boy.

I also didn’t play Zork Zero or the [illustrated] games that came after it because I had gone off to college and didn’t have the Apple II anymore. But I did catch up with all of them a few years later.

You mention that you did get some adventure games from other companies when you first got the Apple II. Did that continue, or were you exclusively loyal to Infocom?

Well, I was haunting the download BBSes and snarfing any pirated game I could. I played Wizardry and Ultima. I didn’t play too many other text adventures. I knew they existed — I had seen ads for Mike Berlyn’s pre-Infocom stuff — but I didn’t really hunt them down because I knew that Infocom was actually better at it. I remember that we had The Wizard and the Princess, which was just clunky and weird and not actually solvable.

I know that you also wrote some of your own text adventures on the Apple II in BASIC, as a lot of people were doing at this time.

Yes. The first one I did was a parody of Enchanter. I called it Enchanter II. It was a joke game that I could upload to the BBSes: “Look, it’s the sequel!” It was very silly. It started out pretending to be an Infocom game, then started throwing in Doctor Who jokes. The closing line was, “You may have lost, but we have gained,” the ending from the Apple II Prisoner game. It was terrible.

But I did write it and release it. Unfortunately, as far as I know it’s lost. I’ve never seen it archived anywhere.

I did Inhumane after that. That was another parody game, but it was meant to have actual puzzles. It was inspired by the Grimtooth’s Traps role-playing books. I liked the idea of people dying in funny ways.

Inhumane is obviously juvenilia, but at the same time it shows some of what was to come in your games. There’s a subversive angle to it: here’s a game full of traps where the objective is to hit all the traps. That’s the way I play a lot of games, but inadvertently. Here that’s the point.

Were you heavily into tabletop RPGs?

No. Tabletop role-playing I was never into. I get performance anxiety when I’m asked to come up with stories on the fly. I just don’t enjoy sitting at a table and being in that position. It’s not my thing.

But I was interested in role-playing scenarios and source books. First, because of the long-term connection to [computer] adventure games, second because they had so much creative world-building and storytelling, just to read. So, yeah. I was interested in tabletop role-playing games but not in actually playing them.

A surprising number of people have told me the same: they never played tabletop RPGs much but they liked the source books. For some people, the imagination that goes into those is enough, it seems.

So, you go off to university. Why did you choose Carnegie Mellon University?

I got rejected by MIT! It was second on the list.

Were you aware that Infocom was connected so closely to MIT?

No. I knew that they were in Cambridge because I subscribed to the Status Line newsletter. There was a running theme of them mentioning stuff around Cambridge. And I’d played The Lurking Horror. But I didn’t have the full context of “these were MIT students who made Zork at MIT.”

I guess it would have made the rejection even more painful if you’d known.

At university, you’re exposed to Unix and the Mac for the first time.

Yes. And to the Internet. And I started learning “real” programming languages like C.

Did you also play games at university?

Yes. I ran into roguelikes for the first time.

Which ones did you play?

I played a fair bit of Advanced Rogue, but I never got good at it. There were people playing NetHack, but it was clear that that was a game where you had to put in a lot of time to make any serious progress. Rogue was a little bit lighter.

Yeah. I never was willing to put in the hours and hours that it takes to get good at those games. Now especially, when I write about so many games, I just don’t have the time to devote 200 hours to NetHack.

You’ve since re-implemented one of your own programming experiments from university, Praser 5.

That was not originally a parser-based text adventure. It was a puzzle stuck inside the CMU filesystem. Every “room” was a directory, connected by symlinks. You literally CDed into the directory and typed “ls,” and the description would pop up in the file listing. Then you would type, “cd up,” “cd left,” whatever, to follow symlinks to other directories. It was an experiment in using the tools of a shared computer system to make an embedded game. The riddles were a matter of running a small executable which was linked in each directory. I used file permissions to give people access to more things as they solved more puzzles.

Much later, after I had learned Inform 6, I did the parser version.

What did you do right after university?

I graduated in 1992, but I wanted to stick around the Pittsburgh area because a lot of my friends hadn’t graduated yet. I got a job in the CMU computer-science department and shacked up with a couple of classmates in a rundown apartment.

That was great. I bought my first Macintosh and started writing stuff on it. That’s when I started working on System’s Twilight. I figured it was time for me to get into my games career. I decided to write a game and release it as shareware to make actual money. So, I bought a tremendous number of Macintosh programming manuals, which I still have.

System’s Twilight has the fingerprints of Cliff Johnson of Fool’s Errand fame all over it.

Yes. It was an homage.

When did you first play his games? Was that at university?

Yeah. Those came out between 1988 and 1992, when I was there. I had a campus job, so I could afford a couple of games. I played them on the campus Macintoshes.

I remember very well being in one of the computer clusters at two in the morning, solving the final meta-puzzle of The Fool’s Errand. I had written down all of the clues the game had fed me on papers that were spread out all over the desk. Every time I used one of the clues, I’d grab the piece of paper, crumple it up, and throw it over my shoulder. When I finished, the desk was empty and I was surrounded by paper.

We had an amazing experience with The Fool’s Errand as well. My wife fell in love with it. It was our obsession for two weeks. When I talked to Cliff Johnson years ago, my wife told me to tell him that he was the only man other than me that she could see herself marrying. I wasn’t sure how to take that.

What were your expectations for System’s Twilight?

I intended to make some money. I didn’t know how much would show up or whether it would lead to more things. It was just something I could do that would be a lot more fun than the programming I was doing in my day job.

Now that you had your own Macintosh and a steady income, I guess you started buying more commercial games again? I know you have a huge love for Myst, which came out around this time.

I was actually a little bit late to Myst. I didn’t play it until 1994, when everybody was already talking about it.

But when you did, it was love at first sight?

Yeah. The combination of the environment and the soundscape was great and the puzzles were fun. It felt like someone was finally doing the graphical adventure right. I’d never gotten into the LucasArts and Sierra versions of graphical adventures because they were sort of parodic, and the environments weren’t actually attractive. They were very pixelated. They just weren’t trying to be immersive. But Myst was doing it right.

As long as we’re on the subject: I guess Riven absolutely blew your mind?

Yes, it did. It was vastly larger and more interesting and more cohesively thought-through than Myst had been. I played it obsessively and solved it and was very happy.

At what point did you get involved with the people who would wind up being the founders of a post-Infocom interactive-fiction community?

In 1993 or 1994, someone pointed me to an open-source Infocom interpreter. I hadn’t really been aware of the technology stack behind Infocom’s games. But now you could pull all of the games off of the Lost Treasures disks and run them on Unix machines. That was kind of interesting.

I don’t remember how I encountered the rec.arts.int-fiction newsgroup. But when I did, people were talking about reverse-engineering the Infocom technology. I wrote an interpreter of my own for [Unix] X Windows that had proportional fonts, command-line editing, command history, scroll bars — all the stuff we take for granted nowadays. I released that, then ported it to the Macintosh. That was my first major interaction with rec.arts.int-fiction.

It must have been around this time that Kevin Wilson made a very historically significant post on Usenet, announcing the very first IF Competition. You submitted A Change in the Weather and won the Inform category. Did you write that game specifically for the Comp?

Let me back up a little bit. In early 1995, I got an offer from a game company in Washington, D.C, called Magnet Interactive, to port games from 3DO to Macintosh. So, I moved to Washington — I was very sad to leave Pittsburgh behind — and rented a terrible little rundown apartment there. I was also making some money from System’s Twilight, and had started working on a sequel, which was to be called Moondials. It was a slog. I had some ideas for puzzles, but the story was just not coming together.

So, when Kevin Wilson said, “Hey, let’s do this thing,” I said, “I’m going to take a break from Moondials and write a text adventure very fast.” The process started with downloading Inform 5 and the manual and reading it. I think I blasted through the manual five times in a week.

The start of the Competition was a little weird because we didn’t yet have the idea of all of the games being made available at the same time. Kevin just said, “Upload your games to the IF Archive.” So, all of the games trickled in at different times. For the second Comp, we settled very firmly on the idea of all games being released at the same time because the 1995 experience was not very satisfactory.

I know that it’s always frustrating to be asked where ideas come from. But sometimes it’s unavoidable, so I’m going to ask it about A Change in the Weather.

I think I was drawing on the general sense of being an introvert and not making friends easily — being separated from people and feeling alienated from my social group. My college experience wasn’t solidly that. I was an introvert, but I was at a computer college, and there were a lot of introverts and introvert-centered social groups. I had friends, had housemates after college, as I said. But I still struggled somewhat with social activities. It was a failure mode I was always aware of, that I might end up on the edge not really talking to people. I drew on that experience in general in creating the scenario of A Change in the Weather.

That’s interesting. From my outsider perspective, I can see that much more in So Far, your next game. It really dwells on this theme of alienation and connection, or the lack thereof. That also strikes me as the game of yours that’s most overtly influenced by Myst. Just from the nature of the environment and the magical-mechanical puzzles. It’s not deserted like Myst, but you can’t interact in any meaningful way with the people who are there — which goes back to this theme of alienation.

I wasn’t thinking of Myst specifically there, but it was part of my background by that point. The direct emotional line in So Far was breaking up with my college girlfriend. That was a couple of years in the past by this point. That had been in Pittsburgh. A lot of the energy for working on System’s Twilight came from suddenly being stuck at home after that relationship ended. I channeled my frustrations into programming.

But then I tried to drop it into So Far as a theme of people being separated. None of the specifics of what had happened were relevant to the game — just the feeling.

By the time of So Far, you were as big as names get in modern interactive fiction. Your next game Lists and Lists was arguably not a game at all. What made you decide to write a LISP tutorial as interactive fiction? Do you have a special relationship with LISP?

Yes! I hate it! I had taken functional-programming courses in college and learned LISP. But I just did not jibe with it at all.

That’s ironic because Infocom’s programming language ZIL was heavily based on LISP.

Right. It was an MIT thing, but it was not my thing. Nevertheless, the concept of building it into the Z-Machine with a practical limit of 64 K of RAM — or really less than that — seemed doable. And I had written a LISP interpreter as a programming exercise during my first or second year in college. So, I was aware of the basics. Doing it in Inform wasn’t a gigantic challenge, just a certain amount of work.

Were you already starting to feel restless with the traditional paradigm of interactive fiction? Right after Lists and Lists, you released The Space Under the Window, which might almost work better if it was implemented in hypertext. It’s almost interactive poetry.

I wasn’t bored with traditional games, but I did want to try different things and see what could be done. And writing in Inform was simple enough that I could just whip out an idea and see whether it worked. That was inspiring the whole community at this point. That was the lesson of the first IF Comp: you can just sit down and try an idea, and a month later people will be talking about it. There was a very rapid fermentation cycle.

Yes. It led to much more formal experimentation. Before the Comp came along, everybody was trying to follow the Infocom model and make big games. But if you have an idea that’s more conceptual or avant garde, it’s often better suited to a smaller game. The Comp created a space for that. If you do something and submit it to the Comp, even if it’s highly experimental, it will get played and noticed and discussed.

Now we come to The Big One of your games in many people’s eyes. And I must admit that this applies to me as well. Spider and Web is such a brilliantly conceived game. I’m in awe of this game. So, thank you for that.

You’re welcome. It’s always tricky to have a game which is so purely built out of a single idea because then, when you try to write another game, you think you have to come up with another idea that’s as good, and it’s never possible.

Was this idea born out of any particular experience, perhaps with other media?

I don’t think it was. I was prying into what we would now call the triangle of identities — prying into the idea that what the game’s text is telling you is a point of view that might have biases behind it. There is a dialog between what the player thinks about the world and what the game thinks about the world, and there can be cracks in between. That led to the idea of using the storytelling of the game to tell a lie, and that there is a truth behind it which can be discerned.

I started with that kernel and started coming up with puzzle scenarios. Here is an outcome that is verifiable. But there’s two different versions of what happened that could have led to that outcome. I’m going to tell one, but the other is going to be the truth. I strung together a few different versions of that. Then I said, okay, if we’re lying, then the introduction of the game has to introduce the lie. So I folded that in from the start. I knew that I wanted a two-part structure: you learn what’s going on, then you make use of all of the information.

The moment of transition between the two is often referred to as simply The Puzzle. It’s been called the best single text-adventure puzzle ever created. Did you realize how special it was at the time?

No. I figured it would be a puzzle. I didn’t understand how much of an impact it would have. I knew that I wanted to surprise players by having a possibility suddenly become available. Here’s a thing that I can do, and I will do it. Any kind of good puzzle solution is a surprise when you think of it. Afterward it seems obvious. I knew I had a good combination of elements to make it work, but I wasn’t thinking about the way that it would reorient the entire history of the game in the player’s head in one fell swoop. I don’t know. Maybe I had an inkling.

What I love is that the game is called Spider and Web. Suddenly when you solve that puzzle, those two categories get reversed. Who is really the spider and who is caught in the web?

The reason I called it Spider and Web was actually the old idiom “What a tangled web we weave when we practice to deceive.” The notion of deception was meant to be part of the title, and the spider was there just to go with the web. But yes, it’s multi-valent.

I know you’re a big reader of science fiction and fantasy. I wouldn’t picture you reading a James Bond novel. What made you decide to go in the direction of spy fiction here?

Honestly, I thought of it as science fiction. The spy fiction was merely because the story was about deception, and somebody had to be fooling somebody. But conceptually, I had it pinned as a science-fiction scenario from some kind of dystopian cold war, but with magically advanced technology.

You entered Hunter, in Darkness into the 1999 IF Comp. It’s a riff on Hunt the Wumpus, which is about the most minimalist imaginable text adventure, if you can even call it that. Your game, by contrast, is a lushly atmospheric, viscerally horrifying fiction. Were you just being cheeky?

Yeah, I was. I just wanted to put in all the stuff that Wumpus didn’t have, without getting away from the core concept. I thought it would be a funny thing to do. I worked really hard on the claustrophobia and the creepy bats. I remember crawling under a chair to try to get the feel of being in a narrow passage and not being able to move around — just to get the bodily sense of that.

Then we have Shade from 2000, which is another of my favorites of your games. Even more than Hunter, in Darkness, it has a horror vibe.

Yes. I leaned into it harder in Shade.

There are all kinds of opinions about what is really going on in Shade. I know you like to let people draw their own conclusions about your games, so I won’t press you on that…

I don’t think there’s a lot of disagreement on the main point, that you’re dying and this is all a hallucination.

Yeah, that was absolutely my take on it, that you’re dying of thirst in the desert. I saw it pointed out in a review that everything you’re trying to do is the opposite of the real problem you have. You’re trying to get out of your apartment in the hallucination, but your real problem is that you are out, lost in the desert. Was that something you were consciously doing, or are we all reading too much into it?

Well, neither. I don’t think I was consciously thinking that way, but that doesn’t mean that you’re reading stuff into it. It’s deliberately ambiguous. I had a lot of images in my head that I threw out at random. I did have the notion that this environment in your apartment was from your past. You really had packed up your apartment and called a taxi and gotten out, and reiterating it was… inappropriate but real. It was in your head while you were having this terrible experience, and it was being replayed by your brain in a broken way. You’re in a place of blinding light — it’s very hot — and the experience you’re replaying is very dim and dark, except that when light occurs it’s painful.

A rare 1999 meeting in the flesh of interactive-fiction luminaries. From left: Andrew Plotkin, Chris Klimas, David Dyte, and Adam Cadre.

Although your games of the 1990s are fondly remembered and still played, you were also making major technical contributions. Probably most important was the Glulx — sorry, I can’t say that word! — virtual machine to let Inform games expand beyond the strictures of Infocom’s old Z-Machine. How did that come about?

No one knows how to pronounce it!

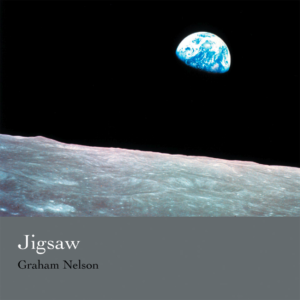

I started to think about it in probably 1996, when Graham [Nelson] came out with version 7 and 8 of the Z-Machine. Version 8 was big — big enough for Graham’s Jigsaw — but it was still just a stopgap. It was only twice as big as Infocom’s version 5. There were all kinds of things that didn’t scale. It seemed worthwhile to make a fresh design that would be 32-bit from the start. I just didn’t want to deal with more incremental changes. And being able to jettison all of the weird legacy stuff about the Z-Machine seemed like a win too — being able to rethink all of these decisions in a technological context that is not 1979.

One of the things I wanted to do was to separate out the input-output layer. I had already written Z-Machine interpreters for X Windows and Mac that used Mark Howell’s ZIP engine with different interface front-ends. When TADS went open-source around 1997, I made an interpreter for that. So, now I had this matrix, right? I’ve got an X Windows front-end and a Mac front-end, and they both slap onto the Z-Machine and the TADS virtual machine. In a pretty clear way, these things are just plug and play. All the virtual machine does is accept text input and generate text output. I mean, yes, there’s the status line, maybe sound and graphics, but fundamentally that’s what it’s doing. And the front-end presents that text in a way that suits the platform on which it’s running. I was doing the same thing that Infocom did, just slicing it into more layers. Infocom had an interpreter and a game file. I said, we’re going to have an interpreter engine and an interpreter front-end. Thus there will be more flexibility.

I designed the front-end first, the Glk library. I made an implementation for Mac and for X Windows and for the Unix command line. Then I started thinking about the virtual machine. I ripped apart the Inform 6 compiler so it could compile to Glulx from the same game source code.

As I recall, the Glulx virtual machine is bigger than the Z-Machine — for all practical purposes, its capacity is infinite — but also simpler. There’s less of the hard-coded stuff that Infocom included, like the object tables.

Yes, exactly. I figured the more generic and simple I could make it, the better. It would be simpler to design and simpler to implement. It adds complexity to the compiler, but the compiler already needs code to generate object tables in a specific format. It would still be doing that, but there wouldn’t be any hardware support for them. I’d just have to include veneer routines to handle object tables in this format. Then, if we ever need to change the format, no problem. We just change the compiler. We don’t need to change the virtual machine.

When did you publish the Glulx specification?

April 1, 1999.

Were you still living in Washington, D.C., at this time?

I had moved around a lot, actually. The job in D.C. only lasted about a year and a half. After the porting project I had been doing finished up, the company dropped me onto a project to do a Highlander licensed game, which we had absolutely no concept of how to do. This would have been like a 3D action game. That project got canned.

Then I worked for a document company in Maryland for a while. Then I moved back to Pittsburgh and worked for a startup. The startup got acquired by Red Hat, and they moved us down to North Carolina. That was from like 1999 to 2000. Then Red Hat fired us and I moved back to Pittsburgh. From 2000 to 2005 I worked for a filesystem company in Pittsburgh.

You took a break from writing interactive fiction for a few years after Shade. Then there was a little bit of a shift in focus when you did come back in 2004 with The Dreamhold. Your earlier games don’t try too hard to be accessible. When you returned, you seemed more interested in outreach and accessibility. What was the thought process there?

Only the obvious one. It’s true that all of my previous games were written very much for the community. They were written for people who knew how IF worked. But The Dreamhold was specifically an outreach game. I wanted to try to expand the community. We’d been doing this for about ten years at that point, and it was kind of the same crowd of people. I thought to create an outreach game as a total wild-ass experiment to try to bring in people from other parts of the gaming world. I didn’t know whether it would work, but I figured it was worth a try. So I designed a game specifically for that purpose, built around explaining how traditional interactive fiction worked to people who didn’t know how to play it.

That meant doing some wacky stuff. There are some rooms in The Dreamhold that you enter by going north, but to go back you have to go east, because I figured, this is really uncomfortable, but people are going to run into this if they get into IF, so they should be familiar with the concept. I’ll try to introduce it as smoothly as possible by putting messages like, “The corridor turns as you head to the north.” Then put in the [room] description, “You can go back the way you came, toward the east,” to try to make it more tangible. But I wanted to introduce complicated maps and darkness and all of the hardcore stuff that the community was used to. And also make it fun.

There were a number of these outreach efforts at the time. Some people were taking IF games to more conventional game jams. There were cheat sheets of “how to play IF” going around. My impression is that these efforts weren’t super successful. Is that your impression as well?

Yes, it is. None of it actually worked. It’s great that we made the on-ramps and it’s good that we still maintain them, but there was not a huge influx of new people coming onto the scene at that point.

My impression is that the community didn’t really start to grow until it opened itself up to non-parser-driven games: the Twine games and ChoiceScript games and so on. Presumably some percentage of those players became willing to try the parser games as well.

Yeah, but that was a little bit later, after 2010 or so. There was still a gap. I decided, well, The Dreamhold didn’t make an impact, so I’m just going to go back to writing wacky puzzle games.

Of course, in 2007 Inform 7 came out. I would say that drew people into creating games, because it was much more approachable for people who were not C programmers. There was a bit of a revolution there. It was just harder to see because it was new authors rather than new players.

The time around 2010 was an exciting one for you personally as well as the community. In addition to the ongoing buzz about Inform 7, Jason Scott released his Get Lamp documentary, and you launched a Kickstarter to make a game called Hadean Lands soon after.

Yes. In 2010, Jason Scott premiered Get Lamp at PAX East. He had interviewed me two or three years earlier — probably in 2007.

Yeah, he worked on that movie for almost ten years.

Exactly. It’s kind of funny to look back at 2007 and see me talking about releasing commercial interactive fiction.

But in 2010, all of the old Infocom guys showed up at PAX East. I was on that panel, sitting with Dave Lebling, Brian Moriarty, and Steve Meretzky. I was going… [genuflecting]

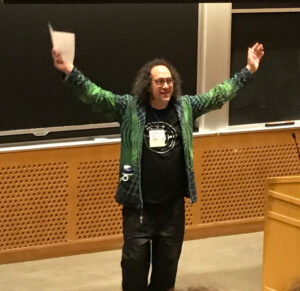

PAX East, 2010. From left: Dave Lebling, Don Woods, Brian Moriarty, Andrew Plotkin, Nick Montfort, Steve Meretzky, and Jason Scott. (Photo by Eric Havir.)

I’m not worthy!

Exactly.

Jason Scott brought Get Lamp to a game class at Tufts University a few weeks later. Since I was living about half a mile away, I came in and said, “Hi, I’m in this movie.” Afterward, I went up to Jason and said, “You know, people are talking about interactive fiction for the first time in fifteen years outside of our little community. Do you think I should do a Kickstarter for a giant IF game?” And Jason looks at me like I’ve got bananas growing out of my ears and says, “Yes, you should!”

He’s the most enthusiastic person in the world.

Yes. And of course, he’d just done a Kickstarter for the Get Lamp release. This was early for Kickstarter. There had been gaming Kickstarter projects before, but no really gigantic ones. So, getting $30,000 for an IF Kickstarter was kind of a big deal in 2010. So I went to the boss at my day job and said, “Well, I guess this is it for us. I’m quitting.” I knew that $30,000 wasn’t actually going to last me very long, living in Boston. But of course, I’d been in the software industry for decades by this point, so I had a fair amount of savings cushion built up. And I had a pile of Red Hat stock which was worth some money. I could live on it while I found my footing as an indie developer.

The Dreamhold had taken me nine months. I thought Hadean Lands would take me a year. Ha! It turned out that writer’s block is a hell of a thing. Hadean Lands kept getting sidelined. I got totally knocked over by the idea of doing a hypertext MUD. I spent a year writing that. That was Seltani, which was hugely popular for about two months in the Myst fan community; I did it as a Myst fan game and presented it at a Myst convention. Everybody loved it. But I wasn’t writing Hadean Lands, and eventually my KickStarter backers started to get upset about that.

I did slog through it. I got Hadean Lands done [in 2014]. I don’t feel like the story is hugely successful, but I’m very happy with the puzzle structure and the game layout.

As you know as well as I do, there’s a whole checkered history of people trying to monetize IF. A few years ago, Bob Bates of Infocom and Legend fame released Thaumistry. I was a beta-tester on that game. The game was very good, but these things just never work. It’s always a disappointment in the end. Nobody has ever cracked that code.

If you look at the Thaumistry Kickstarter and the Hadean Lands Kickstarter, you see that they made almost the same amount of money from almost the same number of backers. It’s the same crowd showing up: “Yeah, we still love ya!” But they’re not enough to make a living from…

The problem is getting outside of that crowd.

It’s no wonder that people like Emily Short have long since decamped, saying, “I have to work on different kinds of games with a larger reach.”

What about you? Do you think you will ever return to parser-based interactive fiction?

That’s a fair question. I’ve had a lot of starts toward things that I thought might be interesting. I started working on a framework for a kind of text game that’s not parser-based but also not hypertext in the sense that Twine is. It’s more combinatoric. I got two-thirds of the way done with building the engine and one-third of the way done with writing a game, then I kind of lost it. But I still think it’s interesting and I might go back to it. I don’t think it would go big the way Twine did, but it might reach a different audience. It’s a different way of thinking about the game structure.

Would you care to talk about your partnership with Jason Shiga to turn his interactive comic books into digital apps? I have played Meanwhile, the first of those.

Sure. I’d been aware of Jason Shiga ever since I started hanging out with Nick Montfort at MIT after I moved to Boston. Nick had a bunch of his early self-published stuff. He had the original printing of Meanwhile, as a black-and-white hand-cut book. I thought it was really neat.

Totally by coincidence, Meanwhile got picked up by a publisher just before that 2010 PAX East we talked about. A nice big hardback version of it was published. It was being sold at PAX East. I thought, man, this is great, I’d really love to do an iPhone version. This was 2010; iPhone games were big.

A little later, I did the Hadean Lands Kickstarter and quit my job. I needed to have more projects than just one text adventure, so I wrote to Jason Shiga and said, “Hey, I’m a big fan. I’d love to do an app version of your book.” Jason was amenable, so we had the usual conversations with lawyers and agents and signed a contract. I worked on that at the same time that I was planning out Hadean Lands. The iPhone app came out in 2011.

So, the finances of making a go of it as an independent creator of digital content without a day job didn’t quite pan out for you in the end. I feel your pain, believe me. It’s a hard row to hoe. What came next?

After Meanwhile and Hadean Lands, I felt very stuck. Jason [Shiga] was off working on non-interactive comics, so there wasn’t anything to do there. I bummed around for a while trying to find something that would make any kind of money at all, but I was not successful.

I’m skipping over huge chunks of time here, but in 2017 Emily Short and Aaron Reed were working on a project to do NPC dialog as a commercial product. It was essentially taking Emily’s old ideas about threaded dialog in parser games and turning them into a plugin which game designers could use in any game to have interesting multi-threaded conversations. I spent a couple of years working on that project with them. But it turned out that management at that company sucked and everybody bailed.

Since then until this year, I’ve been working for big and small games studios, working on the dialog parts of their games.

Coding dialog engines or writing dialog?

I’ve been a software engineer, working on the coding part, but working with the writers.

Also during this period, Jason Shiga started writing what he calls “Adventuregame Comics,” which are shorter Meanwhile-style books. I’ve started porting those. The Steam port of The Beyond and the iOS and Steam port of Leviathan are available now. The iOS port of The Beyond will be coming later.

Since Hadean Lands, you’ve stepped into more of an organizing role in the IF community.

Yes. I’m very proud to have transitioned from being a hotshot game writer to someone who is doing community support, building structures and traditions and conferences. I never wanted to be a person who was only famous for writing games, especially after I started writing fewer games. I really didn’t want to be a person who was famous for having been a big game writer in the 1990s. That’s a sucky position to be stuck in. There needs to be a second act.

It’s maybe a maturation process as well. When you get a little bit older, you realize that some things are important in a way you may not have when you were a young, hotshot game writer.

Yeah. I slowed down writing games because I started to second-guess myself too much. When you’ve written a lot of games that people got really excited about…

Then you’re competing with your own back catalog.

It doesn’t feel good. I’ve had trouble getting away from that.

You’ve done most of your organizational work in the context of the Interactive Fiction Technology Foundation, so maybe we should talk about that more specifically. I’ll give you my impression of the reasons for its founding, and you can tell me if I’m right. You and some other people decided it would be wise to institutionalize things a little bit more, so that the community is no longer so dependent on individuals who come and go. With a foundation and a funding model and all of these institutional aspects, hopefully you set up the community for the long haul, so that it can survive if a server goes down or someone goes away.

Yeah, that’s exactly where it started. We’d been running for decades on people just setting up a server somewhere and saying, “Hey, I’ll run this thing!” That was the original IF Archive, the Usenet newsgroups, IF Comp, the Interactive Fiction Database, the IF Forum. It was workable, but everything was being paid out of somebody’s pocket. There wasn’t a lot of discussion about who was doing what or how much it cost. There was no fallback plan and no thinking about what would come next if somebody stopped doing something. Like, there was a long period when IFDB wasn’t getting any updates because Mike Roberts had a day job. Some things about it were clunky and hard to use, but you couldn’t fix them.

So, in 2015 or early 2016, Jason McIntosh, who was running the IF Comp at that point, had a conversation with somebody who said, “Why don’t you have a non-profit organization to support the IF Comp? Then you could get donations from people.” And Jason started running around in circles with a gleam in his eye, saying, “Yes! We should do this! We should do this! Whom do I know who can help?” He started talking to other people who were longtime supporters of things in the community. That included Chris Klimas, who had been supporting Twine for three or four years, and me — I’d been supporting the IF Archive for a while. Then Carolyn VanEseltine and Flourish Klink joined. Flourish was the only one who knew how to set up a non-profit. They had run a Harry Potter fan conference as a teenager, and, being excited and not knowing things were hard, had just done it.

We got into contact with the same lawyer Flourish had used. The lawyer told us what we needed: forms, bylaws, etc. Jason was the first president, I was the first treasurer. We went down to my bank and opened a business account for the organization. Then we wrote to the IRS to become a 501 C3 non-profit. We set up a website, found someone to give us a basic Web design and a logo. Then we announced it.

At the start, we just did the IF Comp; we collected about $8000 that first year for a prize pool. But over the course of the first couple of years, we added Twine and the IF Archive. The IF Forum was the next big addition. Then the IF Wiki and IFDB. Today each has its own steering group. And we have a grants committee now.

The NarraScope conference is another IFTF project. Would you like to tell a bit about that?

That was my idea. I’d always been keen on the idea of having a narrative-game-oriented conference. I’d been going to GDC for many years. GDC has a sub-track, a narrative-game summit, which is where people like Emily Short and Jon Ingold hang out. But it’s a very tiny slice of what GDC is. And of course GDC is expensive, so it’s hard to bring in the hobbyists and the indie people and the people who write IF Comp games. They just can’t afford GDC. I wanted to provide an alternative that was more approachable and affordable and friendly.

Once we as an organization had steady members and contributors and could bring in money, I said, “It’s time to think about a conference. Our first de novo project.” So, I talked to people I knew who had been involved in conferences, like the Myst fan conference, which is a very tiny thing that happens every year, like 100 people. But it’s been going for years and years. And of course Flourish had run a fan conference.

In 2017 or 2018, I went to GDC with a bunch of business cards that said, “We want to run an interactive-fiction, adventure, and narrative-oriented game conference. Want to help us?” I handed one to everybody I talked to. I found a bunch of people who were interested in helping. Nick Montfort said he could get us a space at MIT for the event relatively cheap. We put up a call for speakers, a website, etc. We were coordinating with the IFTF Education Committee, which is run by Judith Pintar, who goes all the way back to Shades of Gray.

Yeah, I had a great talk with Judith some years ago now.

I had strong opinions about how a friendly conference should feel. We had to bring in lunch so people would sit around and have conversations rather than splitting up and running all over Cambridge. I wanted long breaks between talks so people would have space to socially interact. I wanted badges that didn’t distinguish between speakers and attendees; we’re all here, and we’re not going to have superstars. I wanted an open and honest tone.

We made sure to have a keynote speaker who wasn’t an old fart. We didn’t want somebody like Scott Adams coming in and talking about what it was like back in the 1980s.

You didn’t want to become a retro-gaming conference.

Right. And we deliberately made the scope larger than just interactive fiction as found in the IF Comp or the IFDB. We didn’t want to limit the conference to those topics. We kept the admission price down to about $85.

That was 2019. We had about 250 people, and everything miraculously went perfectly. The worst disaster was when the Dunkin’ Donuts guy was dropping off coffee and hot cocoa. One of the urns blew its spout and dumped gallons of cocoa all over the floor. Someone said, “I know where there’s a mop,” and went and got the mop and cleaned it up. Great, let’s have the rest of the conference!

Local game companies made contributions, maybe $500 or $1000. Between that and the registration fees, the conference broke even. I admit that I threw in $2000 myself to make it balance, but that was because we splurged out and rented a bar on Sunday night. I said, okay, I’ll cover that, so that everybody can go out and have pizza and beer.

It was a huge success. We said we would do it again next year. But of course next year was 2020. You know how that story goes.

But it was exciting enough that we wanted to keep going anyway, so we had an online event in 2020. We skipped 2021, then came back in 2022 with an online conference. Then we had a hybrid model for 2023 in Pittsburgh and 2024 in Rochester. And that’s the history of the thing in a nutshell. By now I’ve become just an advisor, which is a great relief.

How many people have attended the later conferences?

It’s very easy to attend an online conference, so about 500 or 600 people signed up for those. But in person in Pittsburgh, there were about 100, either because people didn’t want to travel in the pandemic era or because we were offering an online option, so a lot of people who could have showed up decided to stay home and watch the stream instead. This year was a little higher, like 120.

You were at the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester this year?

Yeah. The space was spread out, which turned out to be a win, because we had to walk through the museum and walk past all the cool exhibits. People were jumping out between talks to explore the museum. It was a really neat space — but unfortunately more expensive than a university.

And there will be another conference in 2025?

There absolutely will. It’s going to be in Philadelphia at Drexel University. NarraScope has not yet become big enough to replace GDC, but we’re optimistic. [smile]

I don’t think you want that. It becomes very bureaucratic and soulless.

Yeah, obviously. But Justin Bortnick, who is the current IFTF president, has been talking to GDC about booth space to present IFTF on the show floor. The Video Game History Foundation had a booth there this year. We thought, we’re educational too! We could do that! It may actually happen.

Maybe we can wind up this conversation by talking about the current status of the IF community itself. For many years, it seemed to be quite stagnant in terms of numbers. We already talked about the outreach efforts that took place around 2005 and largely did not succeed. But about five years later, the hypertext systems started to come online. There was a big jump at that point. If you look at the number of games entered in the Comp, they actually trend down through the 2000s, then suddenly there’s a big spike around 2010 to 2012. They’ve stayed at quite a high level since then. Do you have a sense of whether these new, presumably younger people are jumping over to the parser-based stuff as well?

There are new faces on both sides. There is now an active group of retro-fans interested in parser games. That is, people who are excited about making new games and running them on Commodore 64s and the like. We had to update Inform to fix the support for the version 3 Z-Machine, which had been broken over time as everybody was writing bigger and bigger games. Now people want to write small games again.

And there is more interest in hybrid systems, intermediate models which are neither pure hypertext nor pure parser. For years and years, there were no new parser tools. I thought the last great parser development systems had already been implemented; people would stick with TADS 3 and Inform 7 forever. Then a parser system called Dialog appeared, which is a little bit different from them.

But there is certainly more energy on the hypertext side, especially because a lot of us old farts have drifted away. I’m not writing games anymore, Emily Short isn’t writing text games anymore, Jon Ingold and Aaron Reed went off and did their things, Adam Cadre went off to work on film scripts. There are new people writing new games, but I think the pool is going to shrink over time. But that’s okay. Everything that Jon Ingold has done at Inkle Studios is informed by the early text games he worked on and how he wanted to expand that to reach a bigger audience. Everything Sam Barlow has done — Her Story, Telling L!es, Immortality — is informed by his experience writing text games. The same goes for Emily Short. It’s still part of the conversation. It’s just not the center of it anymore.

Yeah. This is a discussion I’ve had from time to time since I started this site. My opinion is that when our generation dies that will probably mark the end of parser-based text adventures. You can say that’s tragic if you want to. At the same time, though, nobody’s writing plays like Shakespeare anymore, but Shakespeare’s plays are still out there.

And there’s still theater.

Yeah. Trends in interactive media, just the same as others forms of entertainment and art, come and go. They have their time, and then their time is over. I’m quite at peace with that.

I’m sort of handicapped by the fact that I haven’t played IF Comp games in quite a while.

I haven’t either. To be honest, I’ve played almost nothing made in the last ten years, just because I have so many old games on the syllabus for this site. Having too many games to play is not the worst problem to have, but it’s made me kind of a time traveler. I live in the past in that sense.

I do know that this year’s IF Comp winner was by Chandler Groover. I don’t think he’s our age. Ryan Veeder is younger than us.

I do look at the Comp website sometimes to see what’s going on. I’ve noticed that it still seems to be a parser-based game that actually wins the thing most of the time. That’s a sign of something, I guess.

Yeah. Maybe it’s a sign of old farts hanging on too long? But seriously, I think there is a new generation of parser-game authors. Whether it’s big enough to sustain itself after you and I are doddering in a nursing home, I don’t know.

There’s been so much progress with computer understanding of natural language. A lot of it is associated with large language models, of course, which is a fraught subject in itself. But I could imagine a system — a front-end — that could take natural language and translate that into something a traditional parser could more readily understand, then funnel it through even an old text adventure. I’m kind of surprised I haven’t heard of anything like that.

Someone did do that as an experiment and posted about it on the forum. Experimenting both with using LLMs on the input side to translate natural language into parserese, and also on the output side to translate generic room descriptions into more flowery, expanded text. I’m more interested in the input side because I like hand-crafted output, but that’s getting into the whole question of AI.

Yes, I have no interest whatsoever in reading AI-generated text in any context.

I think there wasn’t a lot of uptake on that idea just because the kind of people who are excited about AI aren’t excited about parser games in the first place. There have been several attempts to make an AI-generated text adventure, but they’ve all been by people who were not good at text adventures and didn’t know what they wanted out of it. There’s AI Dungeon, which uses an LLM to pretend to be a parser game. But because it’s all AI generated, it doesn’t really produce anything interesting.

The people who are interested in making parser games are mostly old-fashioned artisans who want to hand-craft everything and are not motivated to dive into AI as a shiny new pool. It might be different if someone who was an established parser-game author jumped in and wholeheartedly tried to make it happen. Revolutions are the result of one person getting involved and building something that takes off. Someone has to actually do the work. And to this point, nobody has done that. It’s very possible the whole AI thing will collapse in six months anyway.

I think that’s a very good possibility, but I think that if it does, it will leave behind some pieces in the rubble that are actually useful. Maybe a solution to our parsing problems can be one of them.

But I’ve kept you long enough. Thanks so much for the talk!

Thank you!

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.