Sometimes these articles come from the strangest places. When I was writing a little while back about The Pandora Directive, the second of the Tex Murphy interactive movies, I lavished with praise its use of a free-roaming first-person 3D perspective, claiming in the process that “first-person 3D otherwise existed only in the form of action-oriented shooters and static, node-based, pre-rendered Myst clones.” Such a blanket statement is just begging to be contradicted, and you folks didn’t disappoint. Our tireless fact-checker Aula rightly noted that I’d forgotten a whole family of action-CRPGs which followed in the wake of Ultima Underworld (another game I’d earlier lavished with praise, as it happened). And, more pertinently for our subject of today, Sarah Walker informed me that “Gremlin’s Normality was an early 1996 point-and-clicker using a DOOM-style engine.”

I must confess that I’d never even heard of Normality at that point, but Sarah’s description of it made me very interested in checking it out. What I found upon doing so was an amiable little game that feels somehow less earthshaking than its innovative technical approach might lead one to expect, but that I nevertheless enjoyed very much. So, I decided to write about it today, as both an example of a road largely not taken in traditional adventure games and as one of those hidden gems that can still surprise even me, a man who dares to don the mantle of an expert in the niche field of interactive narratives of the past.

The story of Normality‘s creation is only a tiny part of the larger story of Gremlin Interactive, the British company responsible for it, which was founded under the name of Gremlin Graphics in 1984 by Ian Stewart and Kevin Norburn, the proprietors of a Sheffield software shop. Impressed by the coding talents of the teenagers who flocked around their store’s demo machines every afternoon and weekend, one-upping one another with ever more audacious feats of programming derring-do, Stewart and Norburn conceived Gremlin as a vehicle for bringing these lads’ inventions to the world. The company’s name became iconic among European owners of Sinclair Spectrums and Commodore 64s, thanks to colorfully cartoony and deviously clever platformers and other types of action games: the Monty Mole series, Thing on a Spring, Bounder, Switchblade, just to name few. When the 1980s came to an end and the 8-bit machines gave way to the Commodore Amiga, MS-DOS, and the new 16-bit consoles, Gremlin navigated the transition reasonably well, keeping their old aesthetic alive through games like Zool whilst also branching out in new directions, such as a groundbreaking line of 3D sports simulations that began with Actua Soccer. Through it all, Gremlin was an institution unto itself in British game development, a rite of passage for countless artists, designers, and programmers, some of whom went on to found companies of their own. (The most famous of Gremlin’s spinoffs is Core Design, which struck international gold in 1996 with Tomb Raider.)

The more specific story of Normality begins with a fellow named Tony Crowther. While still a teenager in the 1980s, he was one of the elite upper echelon of early British game programmers, who were feted in the gaming magazines like rock stars. A Sheffield lad himself, Crowther’s fame actually predated the founding of Gremlin, but his path converged with its on a number of occasions afterward. Unlike many of his rock-star peers, he was able to sustain his career if not his personal name recognition into the 1990s, when lone-wolf programmers were replaced by teams and project budgets and timelines increased exponentially. He remembers his first sight of id Software’s DOOM as a watershed moment in his professional life: “This was the first game I had seen with 3D graphics, and with what appeared to be a free-roaming camera in the world.” It was, in short, the game that would change everything. Crowther immediately started working on a DOOM-style 3D engine of his own.

He brought the engine, which he called True3D, with him to Gremlin Interactive when he accepted the title of Technical Consultant there in early 1994. “I proposed two game scenarios” for using it, he says. “Gremlin went with the devil theme; the other was a generic monster game.”

The “devil theme” would become Realms of the Haunting, a crazily ambitious and expensive project that would take well over two years to bring to fruition, that would wind up filling four CDs with DOOM-style carnage, adventure-style dialogs and puzzle solving, a complicated storyline involving a globe-spanning occult conspiracy of evil (yes, yet another one), and 90 minutes of video footage of human actors (this was the mid-1990s, after all). We’ll have a closer look at this shaggy beast in a later article.

Today’s more modest subject of inquiry was born in the head of one Adrian Carless, a long-serving designer, artist, writer, and general jack-of-all-trades at Gremlin. He simply “thought it would be cool to make an adventure game in a DOOM-style engine. Realms of the Haunting was already underway, so why not make two games with the same engine?” And so Normality, Realms of the Haunting‘s irreverent little brother, was born. A small team of about half a dozen made it their labor of love for some eighteen months, shepherding it to a European release in the spring of 1996. It saw a North American release, under the auspices of the publisher Interplay, several months later.

To the extent that it’s remembered at all, Normality is known first and foremost today for its free-roaming first-person 3D engine — an approach that had long since become ubiquitous in the realm of action games, where “DOOM clones” were a dime a dozen by 1996, but was known to adventure gamers only thanks to Access Software’s Tex Murphy games. Given this, it might be wise for us to review the general state of adventure-game visuals circa 1996.

By this point, graphical adventures had bifurcated into two distinct groups whose Venn diagram of fans overlapped somewhat, but perhaps not as much as one might expect. The older approach was the third-person point-and-click game, which had evolved out of the 1980s efforts of Sierra and LucasArts. Each location in one of these games was built from a background of hand-drawn pixel art, with the player character, non-player characters, and other interactive objects superimposed upon it as sprites. Because drawing each bespoke location was so intensive in terms of human labor, there tended to be relatively few of them to visit in any given game. But by way of compensation, these games usually offered fairly rich storylines and a fair degree of dynamism in terms of their worlds and the characters that inhabited them. Puzzles tended to be of the object-oriented sort — i.e., a matter of using this thing from your inventory on this other thing.

The alternative approach was pioneered and eternally defined by Myst, a game from the tiny studio Cyan Productions that first appeared on the Macintosh in late 1993 and went on to sell over 6 million copies across a range of platforms. Like DOOM and its ilk, Myst and its many imitators presented a virtual world to their players from a first-person perspective, and relied on 3D graphics rendered by a computer using mathematical algorithms rather than hand-drawn pixel art. In all other ways, however, they were DOOM‘s polar opposite. Rather than corridors teeming with monsters to shoot, they offered up deserted, often deliberately surreal — some would say “sterile” — worlds for their players to explore. And rather than letting players roam freely through said worlds, they presented them as a set of discrete nodes that they could hop between.

Why did they choose this slightly awkward approach? As happens so often in game development, the answer has everything to do with technological tradeoffs. Both DOOM and Myst were 3D-rendered; their differences came down to where and when that rendering took place. DOOM created its visuals on the fly, which meant that the player could go anywhere in the world but which limited the environment’s visual fidelity to what an ordinary consumer-grade computer of the time could render at a decent frame rate. Myst, on the other hand, was built from pre-rendered scenes: scenes that had been rendered beforehand on a high-end computer, then saved to disk as ordinary graphics files — effectively converted into pixel art. This work stream let studios turn out far more images far more quickly than even an army of human pixel-artists could have managed, but forced them to construct their worlds as a network of arbitrarily fixed nodes and views which many players — myself among them — can find confusing to navigate. Further, these views were not easy to alter in any sort of way after they had been rendered, which sharply limited the dynamism of Myst clones in comparison to traditional third-person adventure games. Thus the deserted quality that became for good or ill one of their trademarks, and their tendency to rely on set-piece puzzles such as slider and button combinations rather than more flexible styles of gameplay. (Myst itself didn’t have a player inventory of any sort — a far cry from the veritable pawn shop’s worth of seemingly random junk one could expect to be toting around by the middle stages of the typical Sierra or LucasArts game.)

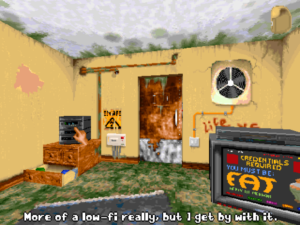

By no means did Normality lift the set of technical constraints I’ve just described. Yet it did serve as a test bed for a different set of tradeoffs from the ones that adventure developers had been accepting before this point. It asked the question of whether you could make an otherwise completely conventional adventure game — unlike its big brother Realms of the Haunting, Normality has no action elements whatsoever — using a Doom-style engine, accepting that the end result would not be as beautiful as Myst but hoping that the world would feel a lot more natural to move around in. And the answer turned out to be — in this critic’s opinion, at any rate — a pretty emphatic yes.

Tony Crowther may have chosen to call his engine True3D, but it is in reality no such thing. Like the DOOM engine which inspired it, it uses an array of tricks and shortcuts to minimize rendering times whilst creating a reasonably convincing subjective experience of inhabiting a 3D space. That said, it does boast some improvements over DOOM: most notably, it lets you look up and down, an essential capability for an old-school adventure game in which the player is expected to scour every inch of her environment for useful thingamabobs. It thus proved in the context of adventure games a thesis that DOOM had already proved for action games: that gains in interactivity can often more than offset losses in visual fidelity. Just being able to, say, look down from a trapdoor above a piece of furniture and see a crucial detail that had been hidden from floor level was something of a revelation for adventure gamers.

You move freely around Normality‘s world using the arrow keys, just as you do in DOOM. (The “WASD” key combination, much less mouse-look, hadn’t yet become commonplace in 1996.) You interact with the things you see on the screen by clicking on them with the mouse. It feels perfectly natural in no time — more natural, I must say, than any Myst clone has ever felt for me. And you won’t feel bored or lonely in Normality, as so many tend to do in that other style of game; its environment changes constantly and it has plenty of characters to talk to. In this respect as in many others, it’s more Sierra and LucasArts than Myst.

The main character of Normality is a fellow named Kent Knutson, who, some people who worked at Gremlin have strongly implied, was rather a chip off the old block of Adrian Carless himself. He’s an unrepentant slacker who just wants to rock out to his tunes, chow down on pizza, and, one has to suspect based on the rest of his persona, toke up until he’s baked to the perfection of a Toll House cookie. Unfortunately, he’s living in a dictatorial dystopia of the near future, in which conformity to the lowest common denominator — the titular Normality — has been elevated to the highest social value, to be ruthlessly enforced by any and all means necessary. When we first meet Kent, he’s just been released from a stint in jail, his punishment for walking down the street humming a non-sanctioned song. Now he’s to spend some more time in house arrest inside his grotty apartment, with a robot guard just outside the door making sure he keeps his television on 24 hours per day, thereby to properly absorb the propaganda of the Dear Leader, a thoroughly unpleasant fellow named Paul Mystalux. With your help, Kent will find a way to bust out of his confinement. Then he’ll meet the most ineffectual group of resistance fighters in history, prove himself worthy to join their dubious ranks, and finally find a way to bring back to his aptly named city of Neutropolis the freedom to let your freak flag fly.

There’s a core of something serious here, as I know all too well; I’ve been researching and writing of late about Chairman Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution in China, whose own excesses in the name of groupthink were every bit as absurd in their way as the ones that take place in Neutropolis. In practice, though, the game is content to play its premise for laughs. As the creators of Normality put it, “It’s possible to draw parallels between Paul [Mystalux] and many of the truly evil dictators in history — Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin — but we won’t do that now because this is supposed to be light-hearted and fun.” It’s far from the worst way in the world to neutralize tyranny; few things are as deflating to the dictators and would-be dictators among us than being laughed at for the pathetic personal insecurities that make them want to commit such terrible crimes against humanity.

This game is the very definition of laddish humor, as unsubtle as a jab in the noggin, as rarefied as a molehill, as erudite as that sports fan who always seems to be sitting next to you at the bar of a Saturday night. And yet it never fails to be likeable. It always has its heart in the right place, always punches up rather than down. What can I say? I’m a simple man, and this game makes me laugh. My favorite line comes when, true adventure gamer that you are, you try to get Kent to sift through a public trashcan for valuable items: “I have enough trash in my apartment already!”

Normality‘s visual aesthetic is in keeping with its humor aesthetic (not to mention Kent’s taste in music): loud, a little crude, even a trifle obnoxious, but hard to hate for all that. The animations were created by motion-capturing real people, but budget and time constraints meant that it didn’t quite work out. “Feet would float and swim, hands wouldn’t meet, and overall things could look rather strange,” admits artist Ricki Martin. “For sure the end results would have been better if it had been hand-animated.” I must respectfully disagree. To my mind, the shambolic animation only adds to the delightfully low-rent feel of the whole — like an old 1980s Dinosaur Jr. record where the tape hiss and distortion are an essential part of the final impression. (In fact, the whole vibe of the game strikes me as more in line with 1980s underground music than the 1990s grunge that was promised in some of its advertising, much less the Britpop that was sweeping its home country at the time.)

But for all its tossed-off-seeming qualities, Normality has its head screwed on tight where it’s important: it proves to be a meticulously designed adventure game, something neither its overall vibe not its creators’ lack of experience with the genre would lead one to expect. Thankfully, they learned from the best; all of the principals recall the heavy influence that LucasArts had on them — so much so that they even tried to duplicate the onscreen font found in classics like The Secret of Monkey Island, Day of the Tentacle, and Sam and Max Hit the Road. The puzzles are often bizarre — they do take place in a bizarre setting, after all — but they always have an identifiable cartoon logic to them, and there are absolutely no dead ends to ruin your day. As a piece of design, Normality thus acquits itself much better than many another game from more established adventure developers. You can solve this one on your own, folks; its worst design sin is an inordinate number of red herrings, which I’m not sure really constitutes a sin at all. It’s wonderful to discover an adventure game that defies the skepticism with which I always approach obscure titles in the genre from unseasoned studios.

The game’s verb menu is capable of frightening small children — or, my wife, who declared it the single ugliest thing I’ve ever subjected her to when I play these weird old games in our living room.

Sometimes Normality‘s humor is sly. These rooms with painted-on furniture are a riff on the tendency of some early 3D engines to appear, shall we say, less than full-bodied.

Normality was released with considerable fanfare in Europe, including a fifteen-page promotional spread in the popular British magazine PC Zone, engineered to look like a creation of the magazine’s editorial staff rather than an advertisement. (Journalistic ethics? Schmethics!) Here and elsewhere, Gremlin plugged the game as a well-nigh revolutionary adventure, thanks to its 3D engine. But the public was less than impressed; the game never caught fire.

In the United States, Interplay tried to inject a bit of star power into the equation by hiring the former teen idol Corey Feldman to re-record all of Kent’s lines; mileages will vary here, but personally I prefer original actor Tom Hill’s more laconic approach to Feldman’s trademark amped-up surfer-dude diction. Regardless, the change in casting did nothing to help Normality‘s fortunes in the United States, where it sank without a trace — as is amply testified by the fact that this lifelong adventure fan never even knew it existed until recently. Few of the magazines bothered to review it at all, and those that did took strangely scant notice of its formal and technical innovations. Scorpia, Computer Gaming World‘s influential adventure columnist, utterly buried the lede, mentioning the 3D interface only in nonchalant passing halfway into her review. Her conclusion? “Normality isn’t bad.” Another reviewer pronounced it “mildly fun and entertaining.” With faint praise like that, who needs criticism?

Those who made Normality have since mused that Gremlin and Interplay’s marketing folks might have leaned a bit too heavily on the game’s innovative presentation at the expense of its humorous premise and characters, and there’s probably something to this. Then again, its idiosyncratic vibe resisted easy encapsulation, and was perhaps of only niche appeal anyway — a mistake, if mistake it be, that LucasArts generally didn’t make. Normality was “‘out there,’ making it hard to put a genre on it,” says Graeme Ing, another artist who worked on the game — “unlike Monkey Island being ‘pirates’ and [Day of the] Tentacle being ‘time travel.'” Yet he admits that “I loved the game for the same reasons. Totally unique, not just a copy of another hit.”

I concur. Despite its innovations, Normality is not a major game in any sense of the word, but sometimes being “major” is overrated. To paraphrase Neil Young, traveling in the middle of the road all the time can become a bore. Therefore this site will always have time for gaming’s ditches — more time than ever, I suspect, as we move deeper into the latter half of the 1990s, an era when gaming’s mainstream was becoming ever more homogenized. My thanks go to Sarah Walker for turning me onto this scruffy outsider, which I’m happy to induct into my own intensely idiosyncratic Hall of Fame.

(Sources: the book A Gremlin in the Works by Mark James Hardisty, which with its digital supplement included gives you some 800 pages on the history of Gremlin Interactive, thus nicely remedying this site’s complete silence on that subject prior to now. It comes highly recommended! Also Computer Gaming World of November 1996, Next Generation of November 1996, PC Zone of May 1996, PC World of September 1996, Retro Gamer 11, 61, and 75.

Normality is available for digital purchase at GOG.com, in a version with the original voice acting. Two tips: remember that you can look up and down using the Page Up and Page Down, and know that you can access the map view to move around the city at any time by pressing “M.” Don’t do what I did: spend more than an hour searching in vain for the exit to a trash silo you thought you were trapped inside — even if that does seem a very Kent thing to do…)