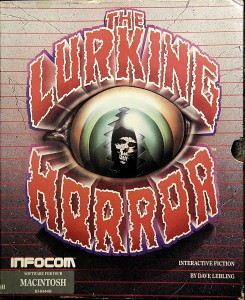

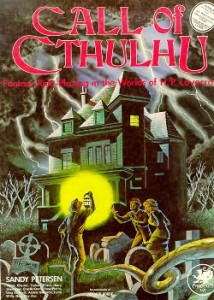

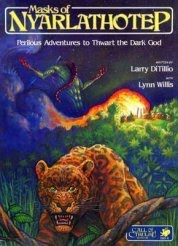

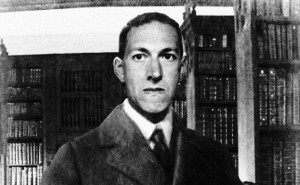

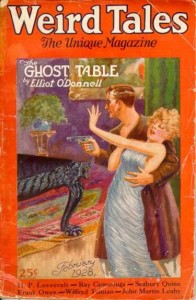

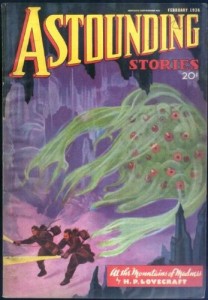

Given the demographics of many readers of H.P. Lovecraft, not to mention players of the Call of Cthulhu RPG, it was inevitable that the Cthulhu Mythos would make it to the computer. The only real surprise is that it took all the way until 1987 for the first full-fledged digital work of Lovecraftian horror to appear. That it should have been among all the Imps of Infocom Dave Lebling who wrote said work is, on the other hand, no surprise. The most voracious and omnivorous reader of all in an office full of them, Lebling was also the only Imp with deep roots in the world of tabletop RPGs; he had to have been aware of Sandy Petersen’s game even if he had never played it.

Running neck and neck as he was with Steve Meretzky for the title of most prolific and recognizable Imp, Lebling was pretty much given carte blanche to choose his projects. Thus his rather vague proposal, for a “kind of H.P. Lovecraft game set at a kind of MIT-ish place,” was all that was needed to set the ball rolling. Not that, even discounting Lebling’s track record, there was a lot of risk in the proposition: horror, while relatively uncommon in adventure games to date, was a fictional genre with obvious appeal for the typical player, and Lovecraft was as good a point of entry as any. Indeed, the graphical adventure Uninvited, which had thrown a bit of Lovecraft into its blender along with lots of other hoary old horror tropes, was doing quite well commercially at the very instant that Lebling was making his proposal. Horror was a perfect growth market for adventure authors and players tired of fantasy, science fiction, and cozy mysteries.

The Lurking Horror‘s title inauspiciously harks back to “The Lurking Fear,” a story from Lovecraft’s Edgar Allan Poe-aping early years that’s not all that fondly regarded even by aficionados. “The tempo increases imperceptibly from sluggish to slow” over the course of the story, and “the awful crescendo of terror that we have been promised is more of an anticlimax,” writes Lovecraft biographer and critic Paul Roland. Ah, well… at least it has a great title, as well as a gloriously cheesy opening line that comes perilously close to “It was a dark and stormy night”: “There was thunder in the air on the night I went to the deserted mansion atop Tempest Mountain to find the lurking fear.”

The game casts you as a freshman at “GUE Tech,” a stand-in for MIT. It’s the end of the term, and your twenty-page paper on “modern analogues of Xenophon’s ‘Anabasis'” is due tomorrow. Lebling cleverly updates the classic Lovecraftian setup of a scholar coming upon a strange and foreboding document in an archive somewhere for the computer age. As you try to work on the paper inside the computer center, alone but for one occasionally helpful but usually infuriating hacker, you find that a strange file has replaced your own, a combination of “incomprehensible gibberish, latinate pseudowords, debased Hebrew and Arabic scripts, and an occasional disquieting phrase in English.” Your directory has somehow gotten mixed up with that of the “Department of Alchemy,” says the hacker. You’ll have to go down there to see if they can help you out. If you first help him out with a little problem of his own, he’s even kind enough to provide you with a key that will open most of the doors down there. And so you set off into the bowels of the university, deserted thanks to the blizzard raging outside on this dark winter night, all the while trying not to think about all the students that have been disappearing lately. Down there in the basements and steam tunnels you’ll encounter the full monty: a zombified janitor; a blood-encrusted sacrificial altar; hordes of rats running who knows where; an insane scientist trying to summon creatures from the beyond; lots of slime and general grossness; and, at last, the tentacled beastie at the heart of it all, who seems to be worming his way into the campus’s computer network to do… well, we’re never quite sure, but chances are it’s not good.

This last is The Lurking Horror‘s one really original contribution to Mythos lore, mixing it up with a bit of William Gibson-style cyberpunk; Neuromancer, another book Lebling had to have read, was the talk of science fiction at the time. The mash-up here anticipates a whole sub-genre (sub-sub-genre?) of stories, even if The Lurking Horror doesn’t do a whole lot with the premise beyond introducing it.

But then much the same thing could be said about the game’s relationship to Lovecraft in general. While most of the surface tropes are present and accounted for, most of the subtext of Lovecraft’s cosmic horror — humanity’s aloneness in a cold and unfeeling cosmos, the utter alienness of the Mythos that places it beyond our conceptions of good and evil, the sheer hopelessness of fighting powers so much greater than ourselves — is conspicuously absent. Likewise the actual creatures and gods of the Cthulhu Mythos; the only proper name from Lovecraft to be found here is that of the author himself, appearing as the name of a file on your computer by way of credit where it’s due. At the time that Lebling was writing the game, Arkham House was still emphatically claiming copyright to Lovecraft’s works, and companies like Chaosium who made use of the Mythos were paying licensing fees. Although Arkham’s claim would eventually prove dubious enough that Chaosium and others would drop the license and continue business as usual without it, it was likely copyright concerns that prompted Lebling not to name names. Unlike many computer games that would follow, The Lurking Horror also evinces no obvious debt to the Call of Cthulhu tabletop RPG beyond the bare fact that both are games that build on Lovecraft’s writings. It’s all enough to make me feel a little embarrassed about the two-article buildup I’ve given this game, afraid that this article might now come across like the mother of all anticlimaxes. I can only ask you to be patient, and to know that those last two articles will pay off in spades down the road, when we encounter games that dig much deeper into Mythos lore than this one does.

Even the language of The Lurking Horror doesn’t quite ever go all-in for Lovecraft in all his unhinged glory. While Lebling gets some credit for using “debased” in an extract I’ve already quoted, there’s not a single “blasphemous” or “eldritch” to be found. Part of the ironic problem here, if problem it be, is that Lebling is just too careful a writer — too good a writer? — to let his id run wild in a babble of feverish adjective in that indelible H.P. Lovecraft way. Consider for example this scene, which finds you peering down through a manhole into a pit of horror.

>look in plate

You peer through the hole, shining your light into the stygian darkness below. The commotion below is growing louder, and suddenly you catch a glimpse of things moving in the pit. Without consciously realizing you have done it, you slam the panel shut, reeling away from the source of such images. Now you know what has been done with the missing students...

Lovecraft would doubtless describe this scene as “indescribable,” and then go nuts describing it. Lebling throws in a Lovecraftian “stygian,” but otherwise much more elegantly describes it as indescribable without having to resort to the actual word, and then… doesn’t describe it. His final line is more subtly chilling than anything Lovecraft ever wrote, a fine illustration of the value of a little restraint. Lebling, it seems, subscribes to the school of horror writing promoted by Edmund Wilson in his famous takedown of Lovecraft, which claims the very avoidance of the overwrought adjectives that Lovecraft loved so much to be key to any effective tale.

Perhaps of more concern than Lebling’s failings as a 1980s reincarnation of Lovecraft is the fact that The Lurking Horror, despite some effectively creepy scenes like the one above, ultimately isn’t all that scary. As I noted in my review of the simultaneously released Stationfall, I find that game, ostensibly another of Steve Meretzky’s easygoing science-fiction comedies, far more unnerving in its latter half than this game ever becomes. The default house voice of Infocom is a sly tone of gentle humor, an unwillingness to take it all too seriously. Just that tone creeps into a number of their more straight-laced works, this one among them, and rather cuts against the grain of the fiction. And in this game in particular one senses a conflict in Lebling that’s far from unique among writers following in Lovecraft’s wake: he wants to pay due homage to the man, but he’s also never quite able to take him seriously. At times The Lurking Horror reads more like a Lovecraft parody than homage, a line that is admittedly thin with a writer as ridiculous in so many ways as Lovecraft. Even more broadly, it sometimes feels like a parody of horror in general. The disembodied hand whom you can befriend, for instance, not only doesn’t feel remotely Lovecraftian but is actually a well-worn trope from about a million schlocky B-movies, played here as it often is there essentially for laughs. After striking an appropriately ominous note at the very end of the game, when an egg of the creature you’ve finally destroyed apparently spawns and flies off to begin causing more havoc, Lebling just can’t leave it at that. Instead he closes The Lurking Horror with a bit of macabre slapstick that’s more Tales From the Crypt than Call of Cthulhu.

>get stone

You pick up the stone. It has a long jagged crack that almost breaks it in half. As you pick it up, you feel it bump to one side. Then, as you are holding it in your hand, something pushes its way out through the crack, breaking the stone into two pieces. Something small, pale, and damp blinks its watery eyes at you. It hisses, gaining strength, and spreads membranous wings. It takes to the air, at first clumsily, then with increased assurance, and disappears into the gloom. One eerie cry drifts back to where you stand.

Something rises out of the mud, slowly straightening. The hacker, mud-covered and weak, staggers to his feet. "Can I have my key back?" he asks.

But the most important reason that The Lurking Horror doesn’t stick to its Lovecraftian guns is down to the other, perhaps even more interesting thing it also wants to be: a tribute to MIT, the university where Infocom was born and where Dave Lebling himself spent more than a decade hacking code, eating Chinese food, and exploring roofs and tunnels.

In choosing to look back with more than a hint of nostalgia rather than to gaze resolutely forward, The Lurking Horror was part of a general trend at Infocom during these latter years of the company’s history, part and parcel of the same phenomenon that saw Steve Meretzky bringing back Floyd at last for Stationfall and, after five years without a Zork, the Imps suddenly pulling out that old name that had made them who they were twice in the space of less than a year. By 1987, with sales far from what they once were and their new corporate overlords at Activision understandably concerned about that reality, a sneaking suspicion that they may be nearing the end game must have been percolating through the ranks. Thus the desire to look back, to appreciate — and not without a little wistfulness — just where they’d been. Lebling himself, meanwhile, was fast closing in on forty, a time that brings a certain reflective state of mind if not a full-fledged crisis to many of us. Whatever else it is, The Lurking Horror is also a very personal game for Dave Lebling, by far the most personal he would ever write.

Since I’ve been writing this blog, I’ve found myself growing more and more skeptical of parser-based interactive fiction’s ability to handle elaborate plotting worthy of a novel or even a novella. The Infocom ideal that was printed on their boxes for all those years, of “waking up inside a story,” was, I’ve come to believe, always something of a lost cause. In compensation, however, I’ve come to be ever more impressed by how good the form is at evoking a sense of place. Despite the name we all chose to apply to our erstwhile text adventures long ago, which I’m certainly not going to try to change now, architecture or landscaping may provide better metaphors for what interactive “fiction” does best. (It’s for this reason, for the record, that I’ve long since backed away from trying to painstakingly define “ludic narrative,” and moved away from an exclusive focus on digital storytelling for this blog as a whole.)

Given all that, I’m particularly fascinated by games like this one that embrace that great — greatest? — strength of the medium by letting us explore a real place. For all of the interactive fiction that’s been made during Infocom’s heyday and after, that’s been done surprisingly little. Only three Infocom games, of which this is the second, attempt to recreate real or historical places. I find The Lurking Horror particularly interesting because the landscape of MIT that it chooses to show us is so personally meaningful to Lebling, turning it into a sort of architecture of memory as well as physical space. I really want to do this aspect of the game justice, and so I have something special planned for you for next week’s article: an in-game guided tour of GUE/MIT.

For now, though, I’ll just note that The Lurking Horror is a worthwhile game if also a somewhat schizophrenic one. The comedy cuts against the horror; the Lovecraft homage cuts against the MIT homage. There’s a lot that Lebling wants to do here, and the 128 K Z-Machine just isn’t quite enough to hold it all. It’s one of the few standard-sized Infocom games that I find myself wishing had been made for the roomier Interactive Fiction Plus format. Still, nothing that is here is really objectionable. The puzzles are uniformly well-done, even if, oddly given that this game came out so close on the heels of Hollywood Hijinx, some of them once again revolve around an elevator. (I suspect a bit of groupthink, not surprising given the collaborative nature of Hollywood Anderson’s game.) And the writing is fine, even if it does feel slightly strangled at times by the space limitations. The Lurking Horror feels a little like a missed opportunity, but it wouldn’t feel that way if what’s here — especially its recreation of MIT student life — wasn’t compelling already.

Infocom had high hopes for both Stationfall and The Lurking Horror, these two simultaneously released games of seemingly high commercial appeal written by their two most prolific and recognizable authors. The pair inspired the last really audacious promotional event in Infocom’s history — indeed, their most expensive and ambitious since the grand Suspect murder-mystery party of two-and-a-half years before. For the 1987 Summer Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago — yes, that era-capping CES again — they rented the Field Museum of Natural History for hundreds of guests, as they had each of the two previous years, and sprung for a local rock band to liven the place up. This time, however, they also hired the famed Second City comedy troupe, incubator of talents like Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi, to come in and perform improvisational comedy (“InfoProvisation”) based largely on Infocom games. From The Status Line‘s article on the event, complete with great 1980s pop-culture references:

Through a hilarious sequence of skits using very few props (a couple of chairs and a piano), the audience saw a computerized dating simulator, roared at a romance between a next-generation computer and a piece of has-been software, met Stationfall’s Floyd, visited GUE Tech, and even had the opportunity to affect the course of a scene or two.

In a tribute to the best-selling Leather Goddesses of Phobos, three vignettes, set in a singles bar and interspersed throughout the program, showed real-life versions of the three playing modes. Tame would have made Mother Teresa proud, but by the time they went from suggestive to lewd, it was enough to make Donna Rice blush.

Steve Meretzky and Dave Lebling even got to join the troupe onstage for a few of the skits. (This must have been a special thrill for Meretzky, who, judging by his love for Woody Allen and for performing in Infocom’s in-office productions, had a little of the frustrated comedian/actor in him, like his erstwhile writing partner Douglas Adams.)

But if the Second City gala harked back to the glory days of Infocom in some ways, the present was all too present in others. The new, cheap packaging was hard for fans to overlook, as was the fact that the principal feelie in The Lurking Horror, a packet of “rattlesnake eggs,” had nothing to do with the game. It looked like something that someone in marketing had just plucked off the discount rack at the local novelty shop — which was in fact largely what it was, as was proved when the final package came out with an equally inexplicable rubber centipede in place of the eggs; apparently it could be sourced even cheaper. The Second City event did get a write-up in newspapers all over the country thanks to being picked up by the Associated Press, but, alas, seems to have done little for actual sales of Stationfall and The Lurking Horror, neither of which reached 25,000 copies. For the regular CES attendees who, whether fans of Infocom’s games or not, had grown to love their parties, this final blowout and its underwhelming aftermath was just one more way that that Summer 1987 edition of the trade show marked the end of an era.

Infocom, however, still wasn’t quite done with The Lurking Horror. A few months after all of the Chicago hoopla, a new version of the game, released only for the Commodore Amiga, reached stores. This one sported digitized sound effects to accompany some of its most exciting moments, a first for Infocom and the first sign of an interest in technical experimentation — not to say gimmickry — that would increasingly mark their last couple of years as a going concern. In this case the innovation came directly from an Activision that was very motivated to find ways to spruce up Infocom’s product line. But, unlike so many of Activision’s suggestions, Infocom actually greeted this one with a fair amount of enthusiasm.

It all began with a creative and innovative programmer named Russell Lieblich, who had come to Activision after spending some time at Peter Langston’s idealistic original incarnation of Lucasfilm Games. During the Jim Levy era Lieblich had been allowed to indulge his artistic muse at Activision, resulting in the interesting if not terribly playable commercial flops Web Dimension and Master of the Lamps. That sort of thing wasn’t going to fly in the new Bruce Davis era, so Lieblich, a talented musician as well as programmer, retrenched to concentrate on the technical aspects of computer audio, a field where he would spend much of his long career in games still to come. Of most relevance to Infocom was the system he developed for playing back digitized sounds recorded from the real world. Infocom had a playtester play through The Lurking Horror again, making a list of everywhere where he could imagine a sound effect. Lebling and others then pruned the list to those places where they felt sound would be most effective, and sent the whole thing off to Lieblich to hack into the Amiga version of the Z-Machine interpreter. At least a few other machines were theoretically capable of playing short digitized sounds of reasonable fidelity as well — the Apple Macintosh and IIGS and the Atari ST would have made excellent candidates — but sound was only added to the Amiga version, an indication of just what an afterthought the whole project really was.

As afterthoughts go, it’s not bad, although the fidelity of the sounds isn’t particularly high even by the standards of other Amiga games of the day. I doubt you’d be able to recognize “the squeal of a rat,” “the creak of an opening hatch,” or “the distinctive ‘thunk’ of an axe biting into flesh” — that’s how The Status Line describes some of the sounds — for what they’re supposed to be if you didn’t have the game in front of you telling you what’s happening. Still, they are creepy in an abstract sort of way, and certainly startling when they play out of the blue. While hardly essential, they do add a little something if you’re willing to jump through a few hoops to get them working on a modern interpreter. Whether the addition of a handful of sound effects was enough to make Amiga owners, madly in love with their computers’ state-of-the-art audiovisual capabilities, consider buying an all-text game was of course another matter entirely.

Next week we’ll put Lovecraft to bed for a while (doubtless dreaming one of his terrible dreams of “night-gaunts”), but will take a deeper dive into the other part of The Lurking Horror‘s split personality, its nostalgic tribute to MIT and student life therein. If you haven’t played The Lurking Horror yet, or if you have but it’s been a while, you may want to wait until then to join me on a guided tour that I think you’ll enjoy.

(Sources: As usual with my Infocom articles, much of this one is drawn from the full Get Lamp interview archives which Jason Scott so kindly shared with me. Thanks again, Jason! Other sources include: the book Game Design Theory and Practice by Richard Rouse III; The Status Line of Summer 1987, Fall 1987, Winter 1987, and Winter/Spring 1988.)