‘Twere better Charity

To leave me in the Atom’s Tomb –

Merry, and Nought, and gay, and numb –

Than this smart Misery.— Emily Dickinson

And so, as another Infocom game once put it, it’s all come down to this. We have indeed come a long way, looked at a lot of history. But now it’s time to refocus on the game of Trinity. Fair warning, then: massive spoilers ahead.

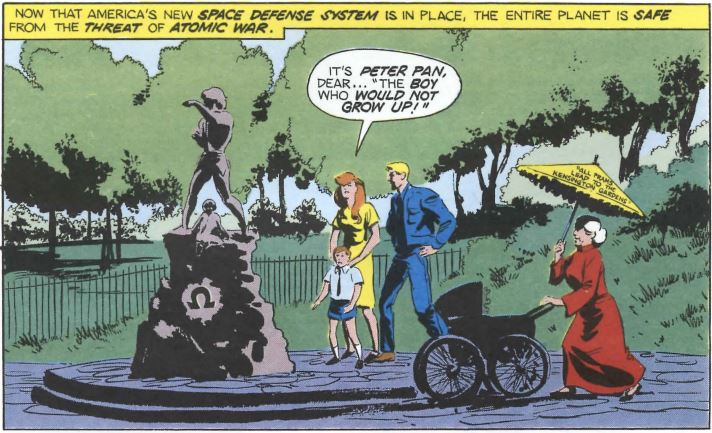

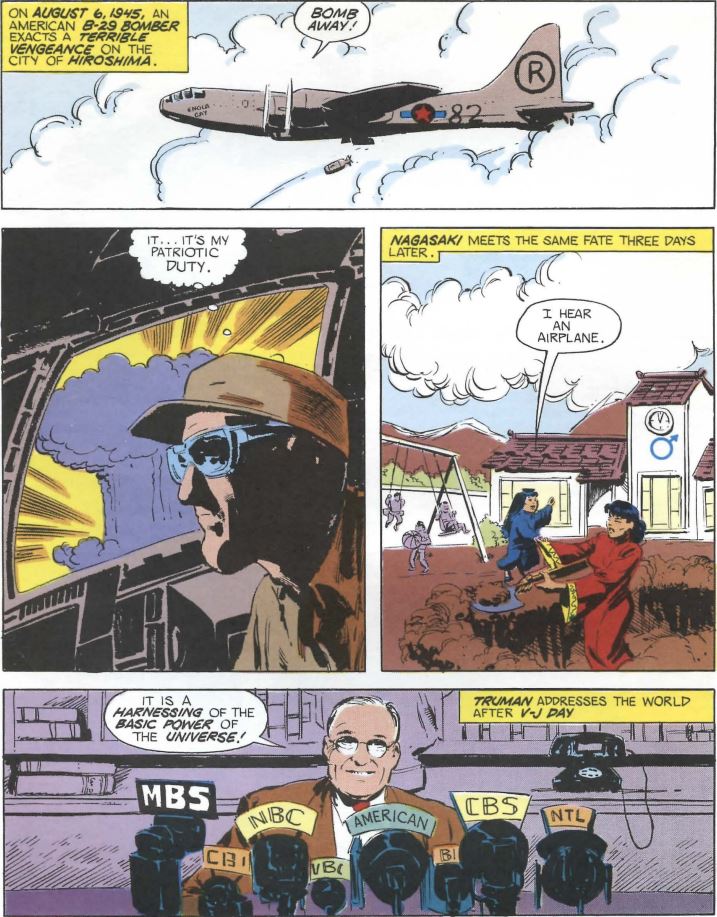

Throughout its considerable length Trinity has constantly implicated the Wabewalker, and through him we who pull his strings, in the tragic history of the atomic age, refusing to allow us the comfort of abstraction. We’ve been forced to cold-bloodedly kill a couple of cute, innocent little would-be pets to show us that killing is ugly and heartbreaking, not a mere matter of shifting columns and figures around on a spreadsheet showing projected death counts. We’ve met the same woman in two different times, once as a happy little girl in Nagasaki just before the bomb dropped and again as an old woman still bearing the visible scars of her suffering there many years later. We’ve frolicked with a dolphin who’s about to be stupidly, senselessly cooked alive by a hydrogen bomb in the name of some ephemeral geopolitical advantage, bringing home to us what these terrible weapons do to the fragile ecosystems of our one and only home. We’ve made a bomb of our own and experienced some of the heady rush that comes with harnessing such elemental forces of nature — the same rush that captured and possibly consumed both Robert Oppenheimer and Edward Teller, each in his own way. We’ve watched history being written down before our eyes into a permanent and remorseless Book of Hours. And we’ve located the fulcrum of history in that fateful moment on the morning of July 16, 1945, way out in the New Mexican desert.

It eventually becomes apparent that the overriding objective of Trinity the game is to sabotage Trinity the first test of an atomic bomb. All of our hopscotching through time has been to set us up for that goal. At last, we achieve it. We expect something triumphant. Surely this means that humanity has been steered away from this senseless course, that all this tragic history we’ve been experiencing has been averted.

Right?

Well, what we get is this:

You slide the blade of the steak knife under the striped wire and pull back on it as hard as you can. The thick insulation cracks under the strain, stretches, frays and splits...

Snap! A shower of sparks erupts from the enclosure. You lose your balance and fall backwards to the floor.

"X-unit just went out again," shouts a voice.

"Which line is it, Baker?"

"Kid's board says it's the informer. The others look okay. We're lettin' it go, Able. The sequencer's running."

The walkie-talkie hisses quietly.

"Congratulations."

You turn, but see no one.

"Zero minus fifteen seconds," crackles the walkie-talkie.

"You should be proud of yourself." Where is that voice coming from? "This gadget would've blown New Mexico right off the map if you hadn't stopped it. Imagine the embarrassment."

A burst of static. "Minus ten seconds."

The space around you articulates. It's not as scary the second time.

"Of course, there's the problem of causality," continues the voice. "If Harry doesn't get his A-bomb, the future that created you cannot occur. And you can't sabotage the test if you're never born, can you?"

The walkie-talkie is fading away. "Five seconds. Four."

The voice chuckles amiably. "Not to worry, though. Nature doesn't know the word 'paradox.' Gotta bleed off that quantum steam somehow. Why, I wouldn't be surprised to see a good-sized bang every time they shoot off one of these gizmos. Just enough fireworks to keep the historians happy."

And then we’re stuck right back where we started, in the Kensington Gardens on the eve of World War III, to do everything we’ve already done all over again… ad infinitum.

There are two levels on which to wrestle with this strange, bitter ending: on the physical, as realistic storyworld plot logic; and on the symbolic or poetic. Let’s start with the first.

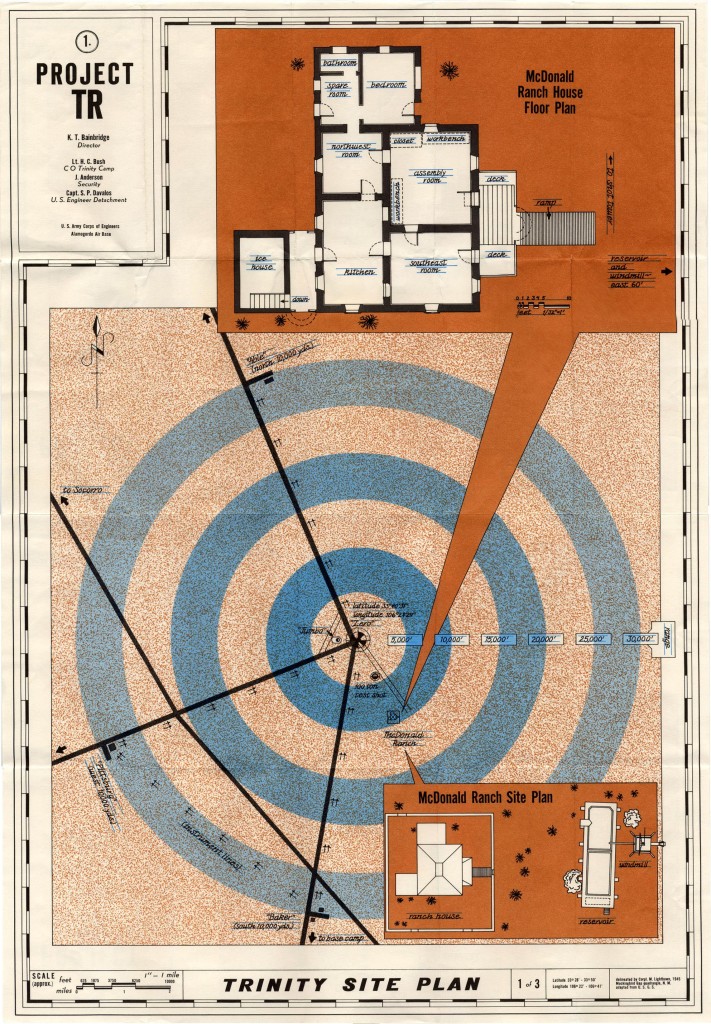

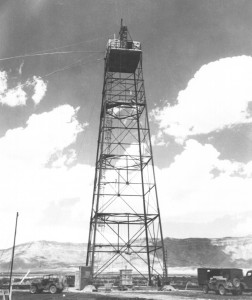

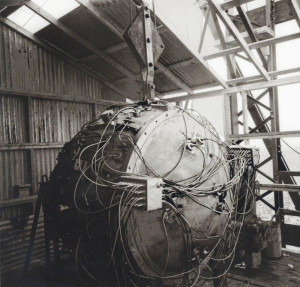

While it’s hardly crystal clear, we can best surmise that Trinity portrays an alternate reality whose laws of physics dictate that that first atomic bomb — and presumably all the ones to follow, should anyone have been able to create them — should have blown up vastly bigger than the scientists who created it expected — and bigger also than the bombs we know from our own reality. Thus the gadget of this subtly different universe “would’ve blown New Mexico right off the map.” Like so much else in Trinity, it’s an idea with an historical basis, which is discussed at some length in The Day the Sun Rose Twice by Ferenc Morton Szasz. This book, published only shortly before Moriarty started working on Trinity, became his bible for the details of the Trinity test; Szasz himself became an informal personal adviser.

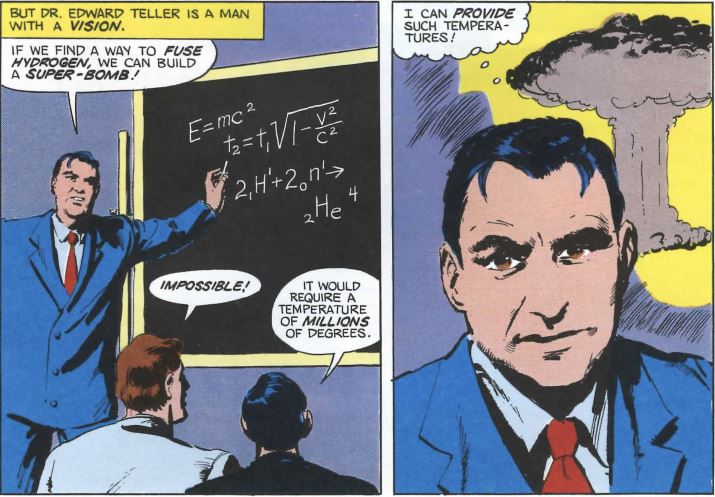

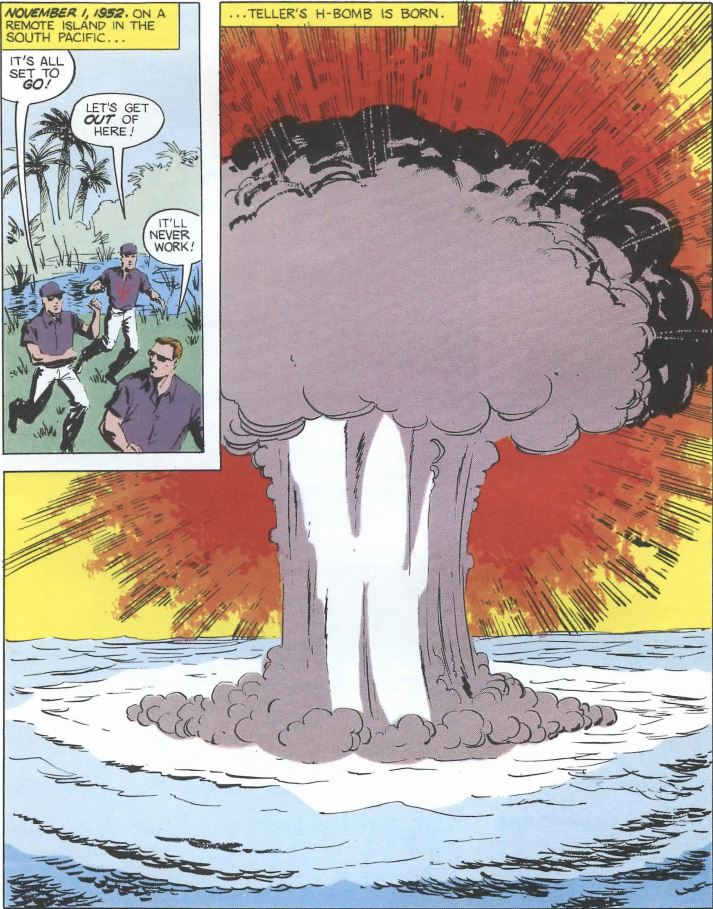

As early as 1922 Nobel Laureate Francis William Aston warned against “tinkering with angry atoms,” voicing concerns that a physicist might accidentally start a chain reaction that would fuse hydrogen in the earth’s atmosphere into helium, the same process that powers the sun — and the hydrogen bomb. The question of whether a human-induced chain reaction taking place inside a bomb could start a runaway chain reaction in the atmosphere at large would continue to nag in the background for a long time, right up through the Trinity test and even well beyond it. In July of 1942, when the Manhattan Project was just getting started in earnest, Edward Teller of all people produced a series of calculations that seemed to show that a fission bomb could in fact create enough heat to ignite the atmosphere. All work came to a halt for several panicked days while the other scientists checked his numbers. It was decided that a probability of better than 1 in 3 million of such an apocalypse actually occurring would be enough to scuttle the Manhattan Project entirely. In the end some of Teller’s numbers were proved to be in error, the probability judged to be somewhat less than 1 in 3 million, and work resumed.

Yet even after they had checked and rechecked their calculations a certain nervousness persisted amongst the scientists preparing for the Trinity test. Enrico Fermi dealt with the question with his typical black humor, offering wagers on whether the bomb would cause a runaway chain reaction at all and, if so, whether it would take out just New Mexico or the whole world. (In either of the latter cases, the winner was likely to be sadly unable to collect…) When the bomb finally exploded, a number of scientists recall an instant of panic at its sheer scale, an instant of wondering if the runaway chain reaction they had all shoved into the backs of their minds was happening before their eyes. Their relief as it became clear that the explosion had reached its limit was perhaps even greater than their relief and sense of triumph that the Manhattan Project had succeeded in its mission.

So, that’s one important part of Trinity‘s ending. But if we can feel ourselves on firm ground with a supersized version of the Trinity bomb absent the Wabewalker’s interference, the rest of what’s happened is rather less clear. Rather than causing the Trinity bomb to simply not work at all, our act of sabotage has merely reduced the scale of its explosion to the Trinity test we know from our own reality — i.e., to the scale the scientists were expecting all along. It seems very hard to believe that cutting a wire would really have allowed the Trinity bomb to blow up nevertheless, only not as big as it otherwise would. Still, we may have to accept the Wabewalker’s act as having had just that outcome. If we do, we must then assume that “bleeding off that quantum steam” entails that all future nuclear explosions will also be reduced in power to correspond with the one that’s just been sabotaged, as a result of some sort of heretofore undiscovered self-correcting quality of the universe. The Wabewalker, whom we might better name Sisyphus, must cycle again and again through time, (partially) sabotaging the Trinity bomb over and over to prevent that paradox that nature “doesn’t know” — the paradox that must be if he doesn’t perform the actions that give birth to the world he knew when he took his $599 London Getaway Package. We might consider him a hero, except that it’s not at all clear that his actions are a net positive. If “blowing New Mexico right off the map” would have led humanity to stop this madness and thus averted the nuclear apocalypse that comes in the Kensington Gardens, then according to the terrible logic of war in the nuclear age the lives of all those New Mexicans would better have been sacrificed in the name of saving billions more all over the world. Our victory in Trinity is the very definition of Pyrrhic.

This chain of conjecture is a sometimes flimsy one, some of its logic a bit wobbly. Yet one feels that trying to parse Trinity‘s ending any more closely gets us into the fan-fiction territory of, say, hardcore Ultima fans trying to reconcile with itself Richard Garriott’s ever-changing world of Britannia, of frantic ret-conning to make sense of things that just, well, don’t make sense. As Andrew Plotkin once said of Trinity‘s ending, “I’ve always been uncertain about how well it hangs together. But just uncertain enough that I think it might be cooler than I am capable of grasping.” It’s Trinity‘s ability to evoke the doubt expressed in that second sentence that may just be its saving grace as a time-travel fiction.

But you know what? I’m not sure how much I care about the real-world logic behind Trinity‘s ending, simply because it’s so powerful on a poetic and philosophical level. Taken as just the culmination of a time-travel puzzle, it’s very clever, yes, if not quite clever enough to feel entirely bulletproof. (Where did the umbrella actually come from? If, as would seem to be implied, that’s your corpse you meet in the magical land, how to reconcile that with the apparently eternal loop you’re stuck in?) It’s clever in a way that any science-fiction fan has seen many times before, clever in the way of that cool twist at the end of a great thriller. Taken more abstractly, however, it becomes much more than merely clever. And it’s on that more abstract level that I find I really want to discuss it.

Before I do that, though, I should take a moment to talk a bit more about why I’m so willing to forgive Trinity its faults as realistic fiction. It’s a question I’ve spent quite some time considering, using as a point of comparison Trinity‘s perpetual point of comparison, Infocom’s other unabashed striving for the mantle of Literature A Mind Forever Voyaging. As many of you doubtless remember, I dinged that game pretty hard for its own various failings as realistic fiction. I therefore owe it to you to explain why I’m so blasé about this aspect of Trinity. One possibility is of course that I simply like Trinity better, and am thus more willing to excuse its failings. However, while the first part of that statement is certainly true, I’m not so sure about the second. Roger Ebert (every gamer’s favorite critic, right?) often used to say that every movie deserves to be reviewed on its own terms — i.e., on the terms of what it’s trying to be. If a movie wants to be a moody art-house character study, how much insight does it give into the proverbial human condition? If it’s a fast-paced action flick, how well does it get the adrenalin pumping? If it’s a porno… well, you get the idea. Unless I’ve misjudged its intent entirely, A Mind Forever Voyaging wants to be a compelling piece of hard science fiction, a realistic extrapolation of current trends in the spirit of the fictions it references on its back cover, Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four. Trinity, though, wants to be something quite different, more poetic than realistic, more a philosophical meditation than a plot-driven story. Particularly when we’re in the magical land that serves as the hub of our historical explorations, we’re literally wandering through a landscape of symbolism, of ideas cast into physical reality. Trinity is a philosophical meditation given the superficial form of a story, like Gulliver’s Travels or Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

I think it’s fair to judge its ending in particular on those terms. I consider Trinity‘s ending to be both the bleakest and the most profound in the Infocom catalog, much more so than that of Infidel in that Moriarty’s ending serves as the essential culmination of his game’s message, not as a mere experiment to see whether a tragic ending could “work” in an interactive medium. Indeed, one could use the word “experiment” to describe most of Infocom’s pre-Trinity nods toward Literature. The ending of Infidel, the friendship and sad fate of Floyd in Planetfall, arguably even the political message and puzzleless structure of A Mind Forever Voyaging were treated almost as technical challenges: “Can we use interactive fiction to do XXX?” Trinity alone feels like a mature, holistic statement rather than an experiment. It doesn’t even bother wasting time on the question: “Of course we can, and now here’s an historical tragedy for ya.”

I want to come back to the idea of Trinity as a tragedy, but first I want to look more closely at another phrase I’ve thrown out there from time to time in this series of articles: this idea of Trinity as a “meditation on history.” Ridiculously simplified, there are two ways of viewing history, of viewing time itself: as a ladder or as a wheel.

History as a ladder is an ongoing process of improvement and perfection. Wars and other terrible things sometimes happen that knock us a notch or two back down the ladder, but we always pick ourselves up and start to climb again. As long as we keep working at it, the lives of most of the people on earth will most of the time continue to get better. It’s an idea that by this point seems intertwined into the very DNA of most Western societies. You can find it in Christianity — particularly Protestant Christianity — whose moral precepts are still at the root of our systems of laws: a Christian, born into a heritage of sin, spends her life striving to overcome that heritage and improve both herself and the world around her, after which she’s rewarded with the ultimate perfection of Heaven. You can find it in our economic systems: capitalism is based on the assumption that we can always make more money than we did the previous year (an assumption which, as Karl Marx among others have pointed out, may not be sustainable in the long term). The United States, amongst the most Christian and the most unabashedly capitalist of Western societies, hews to the idea particularly closely: what else is the American Dream but an idealized narrative of personal improvement and eventual perfection, a secular version of Christianity’s spiritual journey? In the euphoric aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union, American historians started enthusiastically writing about “the end of history,” declaring the world to have reached the top of the ladder and attained perfection at last — in, naturally, the image of the United States. But I’m not here to condemn the notion of history as progress. Far from it. As an American myself, it’s largely the way I too see the world — and, I would even say, with good reason. Still, we should give due weight to the other point of view.

Circumstances come and go, says the circular view of history, but through it all there is the Eternal Now. As the Book of Ecclesiastes, one of the most beloved and most theologically problematic books of the Old Testament, says: “The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.” It’s a view that’s actually even older than Ecclesiastes, stretching back to the pre-Socratic Greek philosophers whose works often survive only as fragments. Since then it’s tended to be most prevalent in non-Western societies. Certainly we can see it in Hinduism and Buddhism with their nearly perpetual reincarnation of the soul rather than the single life as a journey toward perfection (or damnation). It was resurrected in the West only in the last few hundred years by the school of European continental philosophy, whose tolerance for ambiguity and subjectivity tends to stand it in opposition to the analytic tradition that dominates in Britain and the United States, with its emphasis on rationalism and empiricism. Thus you can find it in Nietzsche’s idea of the Eternal Recurrence. You can find it in our old friend Robert Pinsky’s metaphor of the Figured Wheel. You can find it in its most nihilistic incarnation in many apocalyptic fictions of the Cold War, such as Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, which posits a humanity destined to pull itself out of the Dark Ages only to destroy its civilization as soon as nuclear weapons are (re)invented, over and over again in a futile cycle of stupidity spanning endless millennia. And of course you can find it in Trinity, which posits your grand adventure to be a perpetual loop — or, to choose another symbol from the game itself, a Klein bottle with no beginning, no end, and no measurable property of progress in between.

Trinity‘s despairing nihilism is a result of Brian Moriarty’s own conviction as of 1986 that nuclear war was inevitable, that it was only a question of “when” and “how,” never “whether.” Any thoughtful person studying the history of atomic weapons and the Cold War as of 1986 could experience the same sense of predestination, the sense of the futility of the individual, that permeates Trinity. Time and time again the reasonable men had been battered down by the paranoid and the power-mad. Robert Oppenheimer’s case is just one example. Another, perhaps more immediate one for Moriarty would have been the story of President Carter, who entered office determined to reduce the United States’s nuclear arsenal to a “minimal deterrence” level of just 100 to 200 missiles and reach reasonable accommodations with the Soviet Union on a host of issues; he exited four years later amidst boycotts and spiking tensions, and having initiated the arms buildup that would go on to become the most extreme in the peacetime history of the country under Ronald Reagan. Against the forces of history, it seemed that even a good and powerful man like Carter was ultimately powerless.

Can I, the individual, alter the course of history? My answer must first depend on whether I believe in free will. Trinity would seem to tell us that we do have free will on an individual, granular level. The Book of Hours we discover in the magical land shows the Wabewalker’s actions in its pages only as he performs them, not before. Yet on the other hand, virtually everything else in the game is set up to make us feel, as Moriarty put it in an interview published immediately after Trinity, “the weight of all this history, crushing you.” There’s not a lot of individual agency allowed by that description, is there? The magical land of metaphor that serves as the spine of the game would certainly seem to represent a view of time that’s mechanistic and eternally recurring. The sun sweeps around and around its perimeter under the control of the mechanical sundial at its center — literally a wheel of time — its shadow falling again and again on the same set of historical events. “No new thing under the sun” indeed. This is the tragic view of history.

And now, having stumbled upon that word yet again, I think it’s time for us to really think about it. Like so many words, it has at least a couple of valid usages. In everyday speech we use it pretty much any time something really sad or really unjust happens to anyone. So, yes, the recent terrorist attacks in Paris and Copenhagen were tragic. But they weren’t tragedies in the philosophical or literary sense that Trinity is a tragedy.

Most of us were inculcated as schoolchildren in another version of tragedy: it’s all about the “tragic flaw.” A noble, virtuous, and capable man is utterly undone by a single failing in his character: perhaps Lust, perhaps Greed, perhaps Ambition, perhaps Jealousy. The tragic hero must of course die for his failing, but in the process of doing so he will be redeemed and restored to at least a measure of his former greatness through self-discovery and acknowledgement of his sins. Originating with Aristotle in roughly 350 BC, it proved to be a conception very well-suited to later Christian societies, for the cycle forms a neat allegory of the central narrative of Christianity: the Creation, the Fall, and Redemption in the after-life. How appropriate then that the earliest great tragedy of the Elizabethan era, Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, not only follows this outline perfectly but has its protagonist directly interacting with metaphysical specters of Christian good and evil.

Still, despite lots of hammering and prodding over the centuries, the tragic flaw actually sits rather uncomfortably upon lots of tragic heroes. What’s the tragic flaw of Oedipus? He quite sensibly did everything he reasonably could to derail the prophecy that he would kill his father and marry his mother, only to have the universe screw him over anyway. What’s the tragic flaw of Hamlet? Some critics have tried to say it’s indecisiveness, but one can’t help but feel that wishy-washyness lacks a certain moral grandeur. What’s next? Messiness as a tragic flaw? (If so, and as anyone who’s ever seen my office will attest, I’m screwed.)

Aristotle’s word that is generally translated as “tragic flaw” is “hamartia.” It’s a term with its origins in archery, where it’s used to refer to a “missing of the mark.” It was removed from this context by Aristotle, and extended to mean any general mistake or failing. Later, Christian translators may have anachronistically inserted the concept into their own worldview, giving it a moral, even spiritual dimension it does not generally possess in Greek tragedy. There is no grand Christian narrative of guilt, punishment, and redemption to be found here, but rather a sort of cosmic joke and an illustration of the powerlessness of even the mightiest in the face of a universe determined to have its way with us no matter what we do. This is the conception of tragedy hinted at in the works of the philosophers who lived during and before the time of Sophocles, well before the time of Aristotle. It’s the conception of tragedy that Nietzsche would rescue and begin to expound in the nineteenth century after centuries of neglect. Trinity also connects itself to these classical currents, not least via another in its arsenal of symbols: the ferryman Charon. In Greek mythology, he carries souls from the land of the living to that of the dead. In Trinity, he carries the Wabewalker to the Trinity site, the beginning of the end.

The ancient Greeks called the elemental, irresistible force of the universe, the “what will be must be” of existence, “physis.” Some people prefer to call it God; some prefer to call it science — or, more specifically and interestingly, physics. Whatever you call it, it can be a bitch sometimes. The real key to Trinity the tragedy may lie in those lines from Hamlet quoted on the back of its box:

The time is out of joint;

O cursed spite, That ever I was

born to set it right!

Hamlet is arrogant enough to believe he’s some sort of Aristotelian tragic hero, destined to “set it right” through his redemptive, sacrificial heroism. What he fails to understand is that the universe is destined to kick his ass no matter what he does. The Wabewalker is arrogant enough to believe in his sweet, clueless American way that he can “fix” history and make everything better. He’s likewise about to get a swift kick in the ass to disabuse him of that notion. Oedipus the King, Hamlet, and Trinity all in fact share a protagonist who’s deluded enough to believe he can prevent or correct a monstrosity that should not be: a son married to his mother in Oedipus; a brother who has committed fratricide and married his sister-in-law in Hamlet; the atomic bomb in Trinity. The joke’s on them. The universe is, as Trinity‘s climactic text implies and as a little game called Zork once stated outright, “self-contained and self-maintaining.”

So, are we left with nothing more than a sick cosmic joke? An essential component of the Aristotelian conception of tragedy is the hero who is redeemed at last through his suffering. Where is the Wabewalker’s redemption? Those of us who play Trinity today can of course take comfort in the fact that what Moriarty saw as inevitable did not come to pass. Instead a hero emerged named Mikhail Gorbachev who, it turned out, actually was capable of breaking the tragic cycle and just possibly saving the world in the way that Oppenheimer, Carter, the Wabewalker, and so many others were not. Because of him life did not imitate Trinity‘s art.

But playing the Gorbachev card is kind of cheating, isn’t it? Is there redemption to be found within Trinity without recourse to external events? I’m not sure I know how to answer this question, how to describe or explain the way that Trinity makes me feel, but I’ll try.

The ancient Greeks talked about something called the “kairos moment,” the orgiastic instance when physis wells up and Great Change happens. Call it God time if you prefer; call it the ineffable transcendence. At that moment we’re at one with the universe, at one with time. The time is no longer out of joint; we’re living in time, oblivious to it. Those scientists in the New Mexico desert experienced a kairos moment when they saw their gadget explode — so awful and so awe-full. Somehow, in a way nobody has ever adequately described and that I certainly can’t begin to, we can also experience a vicarious kairos time at the culminating moment of tragedy, stare into the abyss and come away redeemed. It’s not about seeking redemption for Oedipus or Hamlet or the Wabewalker. It’s redemption for us.

When Nietzsche wrote of a wheel of time, of the Eternal Recurrence, it wasn’t an exercise in nihilism. Just the opposite. He was looking for a way to escape from the tyranny of linear chronology, from the eternal tragedy of the human condition, which is to live out of joint with time, always casting our mental gaze forward or backward, almost never living in the Eternal Now that is Life. If you’re like me, maybe you feel a bit wistful from time to time when you watch your pets play or eat or love, completely in the moment. They have something we can only touch occasionally, unpredictably. And yet it’s important to try. Because even if the world is headed to hell, even if the missiles are going to fly tomorrow, we have the Now. Because even if our individual Books of Hours are already completely written and we can’t do a damn thing about any of it, we still have the Now. Inside Trinity, we wind up after the supreme futility of the sabotage that wasn’t quite the sabotage we thought it was back in the Kensington Gardens. Okay, fair enough. Let’s take a stroll, feel the sun on our skin, enjoy the happy babble of life around us. Who cares if this is the last moment ever? It’s a moment, isn’t it? Pity to waste it. Anyway, last I checked there was a soccer ball and a perambulator and an umbrella to be gathered…