There’s lots of somethings to be said for sheer audacity in art, for a willingness to stick your neck out and give your audience something they never, ever expected from you. I think sometimes about how the first folks who listened to Revolver must have felt when the erstwhile cuddly Fab Four unleashed the otherworldly chaos of “Tomorrow Never Knows”; how the first buyers of Achtung, Baby must have felt when they hit the play button and heard not the expected soaring anthem but the grinding industrial murk of “Zoo Station”; how, to choose something I’ve already written a bit about here on this blog, viewers who tuned into The Prisoner‘s “Living in Harmony” episode must have felt when instead of a spy drama they got a Western that refused to reveal itself as a dream sequence but instead just kept going and going right through the show’s running time. Lots and lots of people run screaming from these sorts of switcheroos. As for me, though… they always send a thrill up my spine. A willingness to rip it up and start again is pretty high on the list of things likely to draw me to a creator.

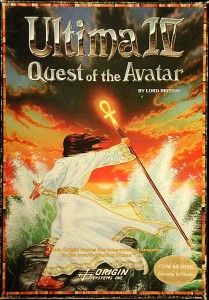

I get some of that thrill when I think about those first people who booted up Ultima IV expecting to create a party via the usual min/maxing routine, only to be greeted with a simple story with the gravitas of a parable — a parable about, well, you.

The day is warm, yet there is a cooling breeze. The latest in a series of personal crises seems insurmountable. You are being pulled apart in all directions.

Yet this afternoon walk in the countryside slowly brings relaxation to your harried mind. The soil and stain of modern high-tech living begins to wash off in layers. That willow tree near the stream looks comfortable and inviting.

The buzz of dragonflies and the whisper of the willow’s swaying branches bring a deep peace. Searching inward for tranquility and happiness, you close your eyes.

A high-pitched cascading sound like crystal wind chimes impinges on your floating awareness. As you open your eyes, you see a shimmering blueness rise from the ground. The sound seems to be emanating from this glowing portal.

There’s the echo of another spiritual journey’s beginning, that undertaken by the narrator of Dante’s Inferno: “In this the midway of our mortal life, I found me in a gloomy wood, astray, gone from the path direct.”

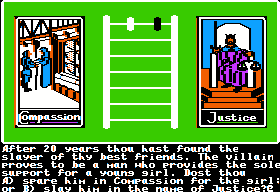

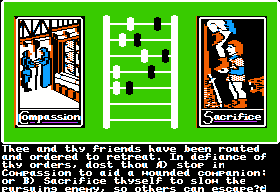

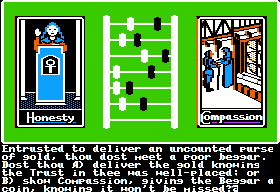

Ultima IV‘s opening parable culminates in a mysterious gypsy fortune teller who poses a series of ethical dilemmas designed to determine not what class or race you’d like to play but what kind of person you are. Of the eight noble virtues of Compassion, Honesty, Honor, Humility, Justice, Sacrifice, Spirituality, and Valor, which ones matter most to you?

By 1985 gaming had already seen its fair share of debates about who the player’s character in a role-playing game or interactive fiction really was. The very term “role-playing” would seem to imply that the player was not just playing herself thrust into another world, that she was playing a role there, performing as one of Gary Gygax’s idealized Shakespearian thespians. Infocom also had tried to sell their players, to decidedly mixed success and occasional howls of outrage, on seeing interactive fiction through the eyes of people who weren’t necessarily the same as them. For the grand experiment of Ultima IV to succeed it was critical that the opposite point of view prevail, that the player feel it to really be her in the game. Richard Garriott: “Since this is a game about the player’s personal virtues, it is very important that one always identifies with the character and feels responsible for the character’s deeds.”

In a computer game if you roll random dice, you’re just going to sit there and go roll, roll, roll. You get all maxed-out numbers and it’s, “Okay, I’ll take that one.” If you don’t let them roll out and you let them choose numbers, well, it’s kind of a fixed equation. Once they know the map and the game, they can make the perfect decision as to exactly what their stats should be if they are aware that the equations are internal. So I don’t want to give you either of those.

Ultima IV I wanted to be a very personal experience. The reason is because in most of these games you are the puppeteer running this puppet around the world. If this puppet is doing bad things it’s not you, it’s the puppet. You can detach. And I wanted this game to be about personal and social responsibility. It is very important that this be you in the world of Britannia, not something you’ve rolled up. If I’m the computer nerd at home wanting to be a big barbarian going around crushing things, I still want to be a computer nerd down there, in nice clothing. The essence of that character is really the essence of you as an individual.

The gypsy’s questions were designed to tease out the player’s real beliefs and place her in the role in the game that best suited her own personality — to whatever extent seven questions determining the most important to her of eight abstract virtues could manage such a feat, of course. Richard again:

We worked on the phrasing of those questions. Unfortunately, there’s no really perfect way to ask those questions that we’ve yet discovered. Here’s something else that’s interesting. When we were working on this system, I said, “Here’s what I want to do for character development.” I went around to everyone in the office, saying, “Here’s these eight virtues along with a short description as to what I mean by them. Give me your ranking, one to eight, as to how important you think they are.” And then about a week later, after we generated those questions, we went back to the same people and said, “Answer these questions.” Although our company was only about twenty people large, everybody except two people had the exact same outcome to the questions as they did to the judgment. And those two who were wrong only had two transposed in the list. And so it turns out you get the exact same responses as you do to an intellectual discussion of it.

For the record, every time I answer the questions Compassion trumps everything else, and thus I end up a bard starting just outside Lord British’s castle. I don’t know whether this necessarily represents the person I always am, but it’s certainly a good approximation of the person I’d most like to be. So, at least for me, the system does indeed seem to work pretty well.

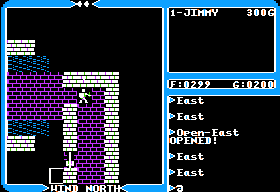

After that radical opening, the screen which greets the player after the gypsy has passed her final judgment must have struck many as comforting in its familiarity.

Yes, we’re back to our familiar view with our familiar alphabet soup of single-letter commands to explore the world. That world is now named Britannia rather than Sosaria; it was so renamed after Lord British united the land under his rule following the passing of the Three Ages of Darkness represented by Ultima I, II, and III. The fact that the geography is completely different from that of the previous game is similarly handwaved away, attributed to a great upheaval — must have been one hell of an upheaval — following the destruction of Exodus in Ultima III. The fact that Ultima II inexplicably took place on our Earth is, as per developing Ultima tradition, completely ignored; there are limits to what even the most dedicated ret-conner can accomplish. Also simply ignored is the last of the stupid attempts at anachronistic cleverness that dogged the early Ultimas, the big reveal at the end of Ultima III that Exodus was really a giant computer; in the Ultima IV manual’s version he was just your everyday world-domination-bent evil wizard.

Importantly, this new world of Britannia that you enter is not under attack from yet another evil wizard, or an evil anything else for that matter. This is one of the few CRPGs ever made, and almost certainly the first, to neither have an evil wizard nor to take place in some melodramatic Age of Darkness. Richard has drawn parallels between the Britannia of Ultima IV and Renaissance Italy — or, even better, King’s Arthur’s Britain at the height of the golden age of Camelot; between the player’s quest to become an Avatar of Virtue and the similarly spiritual quest for the Holy Grail. This quest is necessary not despite the land being peaceful and prosperous but because of it, because times of peace and prosperity are the only ones that allow the luxury of pondering a philosophy for living.

That said, becoming an Avatar of Virtue actually represents only the first step of the two-step process of solving Ultima IV. The second step requires you to descend into the Stygian Abyss, a remnant of the Dante-inspired Hell that was the centerpiece of Richard’s first conception for the game, and recover something called the Codex of Ultimate Wisdom. The final dungeon serves to hammer home the game’s rhetorical message via a series of puzzles which require you to apply what you’ve learned about the system of virtues, but everything that happens after you become an Avatar is otherwise much less interesting than what happens before. Just as what the Holy Grail represents to Lancelot is far more important to the legend than Galahad’s eventual drinking from it, the recovery of the physical Codex comes as something of an anticlimax to your achievement of Avatarhood. Richard Garriott himself said as much in later interviews, calling the Codex “largely irrelevant” to the real message of Ultima IV, even admitting that he had trouble remembering where or what the Codex actually was. Mostly it just allows Ultima IV a bit more of a traditional CRPG structure, serving as a stand-in for the usual evil wizard’s Whatchamacallit of Infinite Power that can be recovered only by defeating him at the bottom of the last and cruelest dungeon.

Let’s talk, then, about that first, more interesting stage of the game. Becoming an Avatar of Virtue requires that you demonstrate your dedication to each of the eight virtues through your deeds over many hours of adventuring in Britannia. When you have proved yourself worthy of “ascension” in a particular virtue, and have collected a necessary entry rune and a mantra, you can visit a shrine to that virtue and meditate to achieve one-eighth of your eventual Avatarhood. Ultima IV boldly applies these sorts of mystical trappings to an ethical philosophy which carefully avoids the subject of God in favor of simple practicality. Richard Garriott: “If I beat you up, you are going to be angry at me and will be on my back. If I’m nice to you, you are likely to be nice back. It makes good rational sense.” This has been expressed more rigorously by philosophers for millennia now as the idea of enlightened self-interest: you do best for yourself by doing well by others. Parsing a distinction which admittedly really exists only in his mind, Richard claims to ignore morals, which to him represent decisions about right and wrong based on feelings or spiritual beliefs, in favor of ethics, which are grounded in simple, rational common sense. A similar determination to remove the supernatural from the fantastic is everywhere in Ultima, perhaps as a byproduct of Richard being the son of a scientist who would probably have become one himself had Dungeons and Dragons and computers not stepped in. Richard saw Ultima IV‘s magic system, for instance, not as something mystical and mysterious but as merely the natural science of a world that just happens to have different natural laws than our own.

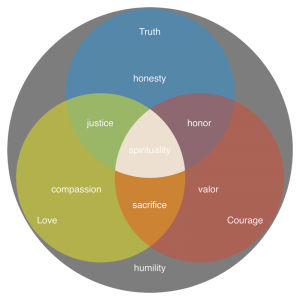

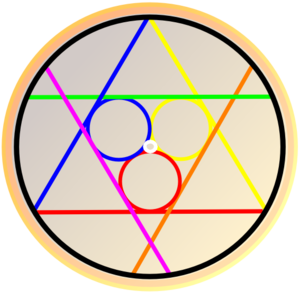

In developing Ultima IV‘s system of ethics, Richard began with a long jumble of possible virtues. Among them were three rather extreme abstractions on this list of abstractions: Truth, Love, and Courage. Watching The Wizard of Oz one day, it struck him that L. Frank Baum may have started with a similar list: “I thought of the Scarecrow looking for a brain, which was Truth; the Tin Man looking for a heart, Love; and the Cowardly Lion, looking for Courage.” It then occurred to his scientist’s mind that these three could be seen as core principles which could be combined to form most of the other items on his list. Honesty is Truth alone; Compassion is Love alone; Valor is Courage alone; Truth tempered by Love is Justice; Love and Courage are Sacrifice; Courage and Truth are Honor; Truth and Love and Courage all together become Spirituality; the absence of all three is Humility. Richard, who loved his symbols, devised a cool-looking diagram to represent the relationships, which ended up inadvertently — or at least subconsciously — resembling Judaism’s Star of David.

The symbol of Ultima IV’s system of virtues. The three traditional primary colors represent the core principles: blue is Truth, red Courage, yellow Love. They combine to form the eight virtues (including Humility, which contains none of the three and is thus the black border).

As a system of belief, it’s perhaps not exactly compelling for an adult (although, hey, cults have been founded on less). As an ethical philosophy… well, let’s just say that Richard Garriott is unlikely to ever rival Kant in university philosophy curricula. There are plenty of points to quibble about: Honesty, Compassion, and Valor are, at least in this formulation, really just synonyms for the core principles that supposedly compose them; the idea that Spirituality is made up of all the virtues lumped together seems kind of strange, as does its presence at all given Richard’s determinedly materialist worldview; the idea of Humility as literally an ethical vacuum seems truly bizarre. (Richard later clarified in interviews that he would have preferred this latter to be Pride, but, “Pride not being a virtue, we have to use Humility”; make of that what you will.) And of course the names of the virtues themselves are rather painfully redolent of the life of a Dungeons and Dragons-obsessed teenager. But poking holes in the system is really missing the point. Ultima IV gave its audience permission to think about these things, laid out in a cool if only superficially logical way. The fact that these ethics still speak the language of Dungeons and Dragons was a good thing, because that’s the language most of Ultima IV‘s audience spoke. Richard himself didn’t claim any mystical truth for the system, freely admitting in interviews that it was essentially arbitrary, that dozens of other formulations could have served his purposes just as well. The one real overriding concern I have with the system is that it can lead to a possibly dangerous ethical absolutism; the only place where Ultima IV does even lip service to the idea that there can be conflicts between its virtues, debate about their merits, is in those questions that open the game. (To his credit, Richard Garriott also spotted the danger, and, indeed, dedicated Ultima V, in many ways an even more thoughtful work than its more heralded predecessor, to exploring the danger of ethical absolutism. Richard characterized that game as, “Now that you’ve shown everybody Avatarhood, let’s show everybody why it’s bad.”)

The way that you build (or lose) mastery of the various virtues is by far the most interesting mechanic in the game, the core thing that makes Ultima IV Ultima IV and the core reason for the game’s stellar reputation today. As you go about your business in its world, Ultima IV is quietly monitoring your actions. If you cheat the blind magic-store proprietor by sneakily paying her less than you should, you lose Honesty; if you’re square with her, you gain it. Running away from enemies costs you Valor; standing and fighting gains it. Giving blood to the healer gains you Sacrifice; refusing costs it. Giving money to beggars gains you Compassion; refusing them… well, you get the picture. Unsurprisingly, the idea has its roots in an admittedly not-widely-used rule in Dungeons and Dragons, which recommends that Dungeon Masters monitor and chart the actions of their players in relation to their professed alignment — “lawful evil,” “chaotic good,” etc. Drift enough and the Dungeon Master could actually impose a new alignment on you, possibly with drastic consequences if, say, your god demanded a certain alignment. In Ultima IV, your progress in the virtues is, inevitably, nothing more than a system of numerical attributes not fundamentally unlike other character attributes — Strength, Experience, Gold, etc. Still, just as Ultima IV tries to make character creation more than a series of dice rolls, it strains mightily to make the virtues an honest reflection of your attitudes and behaviors rather than just a system to be optimized. It hides all of the numbers from you. The only way to learn of your progress in the virtues is to visit the Seer Hawkwind in Lord British’s castle, and even then he just describes your progress in vague generalities. Especially in this day and age, when all of the virtue system’s mechanics have been meticulously documented, we understand all too well that it’s possible to, say, raise Compassion to Avatar level just by giving over and over to the same beggar in the same town. But back in the day particularly, when the system’s underpinnings were not so well understood, it really did feel organic.

The other mechanics of solving Ultima IV — the minutiae of classes and equipment and monsters and leveling up, the puzzles and quests and how to solve them, the locations of towns and dungeons and shrines and artifacts, the seven companions (each representing one of the seven virtues you didn’t choose as most important to you at the beginning of the game) you must eventually round up to complete your adventuring party, etc., etc. — have likewise already been documented as extensively as those of any videogame ever produced. In addition to the countless FAQs, blogs, and web sites generated by the franchise’s many still-rabid fans, at least half a dozen entire books have been published with detailed descriptions of exactly how to best play and solve the game. Most of the nuts and bolts of Ultima IV‘s engine merely extend the technology that Richard had already built through Ultima III in fairly commonsense ways; Richard has often stated that Akalabeth through Ultima III were mostly about improving his technology, Ultima IV about applying his technology at long last to a really worthwhile design. So, I’m not going to talk about most of that in a great deal of depth here; there’s little or nothing I could add to the mountain of practical data at every web surfer’s fingertips, and few fundamental changes to note in the mechanics I described in earlier articles about the franchise. You’ve got a (larger) world map to traverse along with cities, towns, castles, and dungeons; you’ve got horses, ships, and other vehicles to acquire; you’ve got food and equipment to manage (along with, this time, spell reagents, and for a party that will eventually number eight rather than the four of Ultima III); you’ve got lots of people to talk to (this time with a keyword-based pseudo-parser to deepen the interactive possibilities); and of course you’ve got monsters to fight. By now you know the drill.

At this point I probably should confess something: I’m far from sold on Ultima IV as a holistic, playable game. Oh, the concept of the virtues that overlays and underlies the whole is as brilliant and inspiring as I and so many others have already said it is. But you don’t spend all that large a percentage of your time in Ultima IV directly engaging with that concept. You rather spend a whole lot of time, easily hundreds of hours worth if you play the game “straight,” without walkthroughs or spoilers, on lots of things that are often less than compelling at best, dull at average, horrifically, unfairly cruel at worst. Take (please!) the much-vaunted new magic system, in which you have to prepare every single spell you cast by buying its reagents and mixing them together one at a time, a process absolutely devoid of interest after you figure out a given spell’s recipe, one that entails about half a dozen key presses for every single spell you prepare; you can easily spend ten minutes just getting the spells ready for a major dungeon expedition. Combat, never a strong point for Ultima, is more infuriating here than ever; you now have to micromanage up to eight characters through the busywork of taking out the endless hordes of uninteresting monsters that constantly attack when you just want to, you know, walk to the next damn town already. (The number of monsters in each attacking group is actually keyed to the number of characters in your party. In an interesting example of unintended consequences, this means that just about all guides to the game recommend keeping to a party of one as long as possible to try to stave off some of the soul-killing boredom of combat for as long as possible.)

Ultima IV itself doesn’t do a very good job of evincing virtues like Compassion, Justice, even Honor. This is a staggeringly difficult game, a fact that gets rather obscured by the fact that most people playing the game and/or writing about it today are mostly replaying it, and usually with the benefit of that aforementioned copious store of FAQs and walkthroughs. Taken without all that, the way a kid who found it under the tree at Christmas 1985 would have had to approach it, it’s honestly hard to imagine anyone solving it unaided. The design is a spiderweb of all but invisible strands; fail to trace any one of them and you won’t win. Most of the cities in the game are marked on the cloth map that came in the package, but just enough are left unmarked that you’ll need to scour the whole map square by tedious square to find everything. One village sits at the center of a huge inland lake, its existence impossible to detect unless you happen to meet a pirate ship on the lake — a vanishingly unusual occurrence — fight it, steal it, and take it for a sail. Or you can find the village if you manifest an apparent death wish and sail a ship on the open ocean directly into a whirlpool. Many of the towns and castles contain critical secret doors that are distinguished by the presence of one extra pixel amidst the grainy graphics.

See that single white dot above the character that looks kind of like a graphics artifact of some sort? That’s a game-critical secret door.

Conversations can be another nightmare. Every character in the game responds to three keywords given in the manual: “Name,” “Job,” and “Health” (no, I don’t know how Richard settled on that particular inexplicable trio). You’re expected to find other keywords by asking about things the character mentions in those three generic openers, in addition to following up on clues gained in other places of the “Ask XX about YY” variety. But, inevitably, the vast majority of promising-looking words any character mentions are actually not keywords at all. Conversations quickly devolve into a rote entering of every noun or active verb a character uses, with 90 percent of them resulting in “That, I cannot help thee with.” Miss one critical word in a conversation out of sloth or negligence, and that’s a clue overlooked, a thread untraced, and your chance for victory undone. Each town or castle, which number sixteen in total, is populated with dozens of individuals. Miss that critical fellow hiding out in a visually impenetrable glade at the extreme edge of the map, and you’re screwed. Miss the single pixel representing a secret door, and you’re screwed. When you finally get to the very bottom of the Stygian Abyss and stand before the Codex of Ultimate Wisdom, if you fail to answer correctly an out-of-left-field question whose answer requires the ability to read Richard Garriott’s mind, you’re screwed — teleported back to the surface to battle your way down through eight levels of the fiercest creatures in the game and try again. If you were playing in 1985, without the benefit of emulator save states, you would get to do this again and again until you gave up or, as many people finally did, called Origin’s hint line for the answer. If none of what I’ve just described sounds like all that much fun, that’s because for all but the most dogged of players of today it’s really not. Like so many old-school adventure designs, it rewards not cleverness but sheer persistence, a willingness to lawnmower through map after conversation after battle no matter how boring it is.

That, then, is the flip side to Ultima IV the transcendent masterwork: Ultima IV the fiddly, borderline unplayable, tedious mishmash. It’s absurdly easy to make any adventure game impossible, which is one of the many reasons that a designer needs playtesters, and lots of them. Richard Garriott, however, had basically no feedback on many parts of his design. In an interview for Computer Gaming World published shortly after the game, he let drop the bombshell that he was the only person who had managed to complete the game when Origin put it in a box and unleashed it on the world.

A few years ago Michael Abbott, academic and “Brainy Gamer,” sparked quite some conversation with a blog post telling how his students had rejected Ultima IV as “boring.” Predictable outrage toward those kids today followed in the comments and the heaps of reaction posts from other bloggers. Yet my own reaction is to side with Dr. Abbott’s students; Ultima IV is, most of the time, pretty boring. Good on them for recognizing this, I say, for refusing to get sucked into doing boring things for the sake of it. I think kids today are at a minimum every bit as smart as those of my generation were when Ultima IV first hit store shelves, thoroughly capable of deciding that a game is mostly just wasting their time. We shouldn’t begrudge them that freedom if more refined entertainments make their verdict an uncomfortable one for us. Ultima IV stands for me as a hugely important work in the history of its medium, but also one that hasn’t stood the test of time all that well. I love to think about it, love the fact that it exists, that Richard Garriott had the courage to make it — but just thinking about playing it makes me tired. Like a work of conceptual art, to some extent the real power of Ultima IV today is just the fact of its existence.

Of course I’m well aware as a digital historian that my modern take on Ultima IV is a fundamentally anachronistic one. In 1985, the game represented an all but unrivaled gateway to imagination. Solving an Ultima wasn’t really the point; these were worlds to explore, to revisit over a period of months or years until the next Ultima came out (Ultima V would be almost three years in arriving). Everything about Ultima IV — packaged in its big, grandiose box with two big, ornate manuals, with its die-cast ankh that countless boys stuck on a chain and wore to school around their necks, with its big cloth map — marked it as something special, something to be cherished and savored.

The ankh would join the Silver Serpent as one of the enduring symbols of Ultima, a supposed visual representation of the Way of the Avatar to stand alongside the diagram of the virtues. It was yet another bit of pop-culture detritus that made its way into Ultima: Richard first saw it in the movie Logan’s Run, where it served as the symbol of an underground resistance movement, thought it looked cool and “positive,” and stuck it in the game. When he learned that it meant “life and rebirth” to ancient Egyptians, that just made it that much cooler.

When you discovered a new village tucked away in some corner of the map you didn’t complain about the unfairness of it all, you rejoiced at having uncovered another corner of this fantastic world. Actually solving the game was something that few managed, but it didn’t really matter that much anyway. The point was the journey. Even the price contributed: showing an instinct for manipulating perception through pricing that would have done Apple proud, Origin’s suggested list price gave the game a street price of $50 to $55, about $20 more than the typical title. Far from cutting into its sales, the high price just made the game all the more desirable, all the more special. This experience of Ultima IV was absolutely specific to its time and place, not something we can recapture today no matter how much we blog or commentate or notate. Yes, the magic of Ultima IV was ephemeral, but in its day it was very, very powerful.

By way of illustration, let me tell you about Brian. Brian was one of my best friends in middle and high school, his attitudes fairly typical of the cracking and pirating underground in which he was quite thoroughly immersed. Like most of his friends in the scene, Brian didn’t so much play games as collect them. He had hundreds, maybe thousands of Commodore 64 floppies containing virtually every remotely notable game released for the platform in North America or Europe. Most got booted once or twice, to see what the graphics were like; a few action games would grab his attention in a bigger way for a while, but were soon set aside in favor of haunting the pirate BBS network and enjoying the social dramas of the cracking scene (let me tell you, teenage girls had nothing on this crew). Ultima IV, though, was different. It’s the only game I can ever remember Brian actually buying, the only one more complicated than Boulderdash for which he read the manual, into which he put a real effort. Like a hundred thousand other kids, he hung the map on his bedroom wall, wore the ankh to school. Oh, I’m pretty sure he never came close to finishing it. He probably played it much less, all told, than most similar kids who didn’t have the same embarrassment of gaming riches from which to choose. But the fact that his teenage heavy-metal nihilism went away when he talked about the virtues, that it awoke some other — better? — part of him that was impervious to every other game… I’ve always remembered that. Ultima, and Ultima IV in particular, was just like that.

Chester Bolingbroke, better known as the CRPG Addict, was another Brian.

I wrote each [virtue] with its definition on an index card and every morning I shuffled the cards and chose one at random. That one, I did my best to practice for the day. If honesty came up, I was careful to tell no lies throughout the day. If it was sacrifice, I looked for ways to do something charitable.

Not many, I suspect, would admit to deriving what amounts to their religion from a computer game. But I had rejected conventional religion even as a pre-teen. I balked at Judeo-Christian doctrines that seemed both haphazard and arbitrary: meticulous rules about food and dress, but none about the need to actively seek out and destroy evil (my interpretation of “valor”); commandments against adultery and sabbath-breaking, but none against assault and slavery. Ultima IV, on the other hand, offered a comprehensive and completely nondenominational — secular, even — system of virtue. It fit me like a glove.

There were hundreds of thousands of kids just like Brian and Chester. Ultima IV caused its players to set aside their angst and their irony and try to improve themselves in school lunch rooms and family dinner tables across the land. It was far from the first game with artistic aspirations, far from the first to want to be about something more than escapism; 1985 alone also brought Mindwheel, A Mind Forever Voyaging, and Balance of Power. But those admittedly more philosophically sophisticated efforts appealed mostly to a different, older audience; the average age of the average Infocom buyer was north of thirty, while very few kids indeed had the wherewithal to corner a Macintosh long enough to play Balance of Power even had they been interested in the vagaries of geopolitics. Part of the magic of Ultima IV was that it had been created by a kid just like the ones who mostly played it, raised on Dungeons and Dragons and Star Wars, more comfortable with a movie than a novel. Richard Garriott spoke their language, came from the same place they were coming from. Ultima IV, the last of the one-man-band Ultimas, still stands as the most personal expression he would ever create. When he said that ethics matter, that we have the power to choose our values and to live according to them, it resonated because it reflected, as art should, his own lived experience. Yes, many of its players would outgrow Ultima IV‘s simplistic take on ethics, just as many would outgrow the game itself. But hopefully few of that small minority who completed it ever forgot its closing exhortation, delivered as it was in Richard Garriott’s best teenage-Dungeon-Master diction:

Thou must know that the quest to become an Avatar is the endless quest of a lifetime. Avatarhood is a living gift. It must always and forever be nurtured to flourish. For if thou dost stray from the paths of virtue, thy way may be lost forever. Return now unto thine own world. Live there as an example to thy people, as our memory of thy gallant deeds serves us.

(You can download Ultima IV for free from GOG.com. Sources for this article are the same as for the last. I borrowed the diagram of the virtues from Eliott Wall.)