I’ve long been interested in the process by which new games turn into new gaming genres or sub-genres.

Most game designers know from the beginning that they will be working within the boundaries of an existing genre, whether due to their own predilections or to instructions handed down from above. A minority are brave and free enough to try something formally different from the norm, but few to none even of them, it seems safe to say, deliberately set out to create a new genre. Yet if the game they make turns into a success, it may be taken as the beginning of just that, even as — and this to me is the really fascinating part — design choices which were actually technological compromises with the Platonic ideal in the designer’s mind are taken as essential, positive parts of the final product.

A classic example of this process is a genre that’s near and dear to my heart: the text adventure. Neither of the creators of the original text adventure — they being Will Crowther and Don Woods — strikes me as a particularly literary sort. I suspect that, if they’d had the technology available to them to do it, they’d have happily made their game into a photorealistic 3D-rendered world to be explored using virtual-reality glasses. As it happened, though, all they had was a text-only screen and a keyboard connected to a time-shared DEC PDP-10. So, they made do, describing the environment in text and accepting input in the form of commands entered at the keyboard.

If we look at what happened over the ten to fifteen years following Adventure‘s arrival in 1977, we see a clear divide between practitioners of the form. Companies like Sierra saw the text-only format as exactly the technological compromise Crowther and Woods may also have seen, and ran away from it as quickly as possible. Others, however — most notably Infocom — embraced text, finding in it an expansive possibility space all its own, even running advertisements touting their lack of graphics as a virtue. The heirs to this legacy still maintain a small but vibrant ludic subculture to this day.

But it’s another, almost equally interesting example of this process that’s the real subject of our interest today: the case of the real-time grid-based dungeon crawler. After the release of Sir-Tech’s turn-based dungeon crawl Wizardry in 1981, it wasn’t hard to imagine what the ideal next step would be: a smooth-scrolling first-person 3D environment running in real time. Yet that was a tall order indeed for the hardware of the time — even for the next generation of 16-bit hardware that began to arrive in the mid-1980s, as exemplified by the Atari ST and the Commodore Amiga. So, when a tiny developer known as FTL decided the time had come to advance the state of the art over Wizardry, they compromised by going to real time but holding onto a discrete grid of locations inside the dungeon of Dungeon Master.

Gamers of today have come to refer to dungeon crawls on a grid as “blobbers,” which is as good a term as any. (The term arises from the way that these games typically “blob” together a party of four or six characters, moving them in lockstep and giving the player a single first-person — first-people? — view of the world.) The Dungeon Master lineage, then, are “real-time blobbers.”

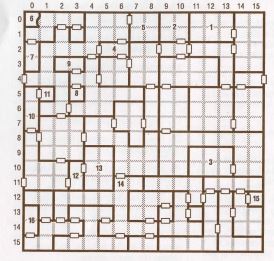

By whatever name, this intermediate step between Wizardry and the free-scrolling ideal came equipped with its own unique set of gameplay affordances. Retaining the grid allowed you to do things that you simply couldn’t otherwise. For one thing, it allowed a game to combine the exciting immediacy of real time with what remains for some of us one of the foremost pleasures of the earlier, Wizardry style of dungeon crawl: the weirdly satisfying process of making your own maps — of slowly filling in the blank spaces on your graph paper, bringing order and understanding to what used to be the chaotic unknown.

This advertisement for the popular turn-based dungeon crawl Might and Magic makes abundantly clear how essential map-making was to the experience of these games. “Even more cartography than the bestselling fantasy game!” What a sales pitch…

But even if you weren’t among the apparent minority who enjoyed that sort of thing, the grid had its advantages, the most significant of which is implied by the very name of “blobber.” It was easy and natural in these games to control a whole party of characters moving in lockstep from square to square, thus retaining another of the foremost pleasures of turn-based games like Wizardry: that of building up not just a single character but a balanced team of them. In a free-scrolling, free-moving game, with its much more precise sense of embodied positioning, such a conceit would have been impossible to maintain. And much of the emergent interactivity of Dungeon Master‘s environment would also have been impossible without the grid. Many of us still recall the eureka moment when we realized that we could kill monsters by luring them into a gate square and pushing a button to bash them on the heads with the thing as it tried to descend, over and over again. Without the neat order of the grid, where a gate occupying a square fills all of that square as it descends, there could have been no eureka.

So, within a couple of years of Dungeon Master‘s release in 1987, the real-time blobber was establishing itself in a positive way, as its own own sub-genre with its own personality, rather than the unsatisfactory compromise it may first have seemed. Today, I’d like to do a quick survey of this popular if fairly brief-lived style of game. We can’t hope to cover all of the real-time blobbers, but we can hit the most interesting highlights.

Most of the games that followed Dungeon Master rely on one or two gimmicks to separate themselves from their illustrious ancestor, while keeping almost everything else the same. Certainly this rule applied to the first big title of the post-Dungeon Master blobber generation, 1989’s Bloodwych. It copies from FTL’s game not only the real-time approach but also its innovative rune-based magic system, and even the conceit of the player selecting her party from a diverse group of heroes who have been frozen in amber. By way of completing the facsimile, Bloodwych eventually got a much more difficult expansion disk, similar to Dungeon Master‘s famously difficult Chaos Strikes Back.

The unique gimmick here is the possibility for two players to play together on the same machine, either cooperatively or competitively, as they choose. A second innovation of sorts is the fact that, in addition to the usual Amiga and Atari ST versions, Bloodwych was also made for the Commodore 64, Amstrad CPC, and Sinclair Spectrum, much more limited 8-bit computers which still owned a substantial chunk of the European market in 1989.

Bloodwych was the work of a two-man team, one handling the programming, the other the graphics. The programmer, one Anthony Taglione, tells an origin story that’s exactly what you’d expect it to be:

Dungeon Master appeared on the ST and what a product it was! Three weeks later we’d played it to death, even taking just a party of short people. My own record is twelve hours with just two characters. I was talking with Mirrorsoft at the time and suggested that I could do a DM conversion for them on the C64. They ummed and arred a lot and Pete [the artist] carried on drawing screens until they finally said, “Yes!” and I said, “No! We’ve got a better design and it’ll be two-player-simultaneous.” They said, “Okay, but we want ST and Amiga as well.”

The two-player mode really is remarkable, especially considering that it works even on the lowly 8-bit systems. The screen is split horizontally, and both parties can roam about the dungeon freely in real time, even fighting one another if the players in control wish it. “An option allowing two players to connect via modem could only have boosted the game’s popularity,” noted Wizardry‘s designer Andrew Greenberg in 1992, in a review of the belated Stateside MS-DOS release. But playing Bloodwych in-person with a friend had to be if anything even more fun.

Unfortunately, the game has little beyond its two-player mode and wider platform availability to recommend it over Dungeon Master. Ironically, many of its problems are down to the need to accommodate the two-player mode. In single-player mode, the display fills barely half of the available screen real estate, meaning that everything is smaller and harder to manipulate than in Dungeon Master. The dungeon design as well, while not being as punishing as some later entries in this field, is nowhere near as clever or creative as that of Dungeon Master, lacking the older game’s gradual, elegant progression in difficulty and complexity. As would soon become all too typical of the sub-genre, Bloodwych offered more levels — some forty of them in all, in contrast to Dungeon Master‘s twelve — in lieu of better ones.

So, played today, Bloodwych doesn’t really have a lot to offer. It was doubtless a more attractive proposition in its own time, when games were expensive and length was taken by many cash-strapped teenage gamers as a virtue unto itself. And of course the multiplayer mode was its wild card; it almost couldn’t help but be fun, at least in the short term. By capitalizing on that unique attribute and the fact that it was the first game out there able to satiate eager fans of Dungeon Master looking for more, Bloodwych did quite well for its publisher.

Captive has the familiar “paper doll” interface of Dungeon Master, but you’re controlling robots here. The five screens along the top will eventually be used for various kinds of telemetry and surveillance as you acquire new capabilities.

The sub-genre’s biggest hit of 1990 — albeit once again only in Europe — evinced more creativity in many respects than Bloodwych, even if its primary claim to fame once again came down to sheer length. Moving the action from a fantasy world into outer space, Captive is a mashup of Dungeon Master and Infocom’s Suspended, if you can imagine such a thing. As a prisoner accused of a crime he didn’t commit, you must free yourself from your cell using four robots which you control remotely. Unsurprisingly, the high-tech complexes they’ll need to explore bear many similarities to a fantasy dungeon.

The programmer, artist, and designer behind Captive was a lone-wolf Briton named Tony Crowther, who had cranked out almost thirty simple games for 8-bit computers before starting on this one, his first for the Amiga and Atari ST. Crowther created the entire game all by himself in about fourteen months, an impressive achievement by any standard.

More so even than for its setting and premise, Captive stands out for its reliance on procedurally-generated “dungeons.” In other words, it doesn’t even try to compete with Dungeon Master‘s masterful level design, but rather goes a different way completely. Each level is generated by the computer on the fly from a single seed number in about three seconds, meaning there’s no need to store any of the levels on disk. After completing the game the first time, the player is given the option of doing it all over again with a new and presumably more difficult set of complexes to explore. This can continue virtually indefinitely; the level generator can produce 65,535 unique levels in all. That should be enough, announced a proud Crowther, to keep someone playing his game for fifty years by his reckoning: “I wanted to create a role-playing game you wouldn’t get bored of — a game that never ends, so you can feasibly play it for years and years.”

Procedural generation tended to be particularly appealing to European developers like Tony Crowther, who worked in smaller groups with tighter budgets than their American counterparts, and whose target platforms generally lacked the hard drives that had become commonplace on American MS-DOS machines by 1990. Yet it’s never been a technique which I find very appealing as anything but a preliminary template generator for a human designer. In Captive as in most games that rely entirely on procedural generation, the process yields an endless progression of soulless levels which all too obviously lack the human touch of those found in a game like Dungeon Master. In our modern era, when brilliant games abound and can often be had for a song, there’s little reason to favor a game with near-infinite amounts of mediocre content over a shorter but more concentrated experience. In Captive‘s day, of course, the situation was very different, making it just one more example of an old game that was, for one reason or another, far more appealing in its own day than it is in ours.

Tony Crowther followed up Captive some eighteen months later with Knightmare, a game based on a children’s reality show of sorts which ran on Britain’s ITV network from 1987 until 1994. The source material is actually far more interesting than this boxed-computer-game derivative. In an early nod toward embodied virtual reality, a team of four children were immersed in a computer-generated dungeon and tasked with finding their way out. It’s an intriguing cultural artifact of Britain’s early fascination with computers and the games they played, well worth a gander on YouTube.

The computer game of Knightmare, however, is less intriguing. Using the Captive engine, but featuring hand-crafted rather than procedurally-generated content this time around, it actually hews far closer to the Dungeon Master template than its predecessor. Indeed, like so many of its peers, it slavishly copies almost every aspect of its inspiration without managing to be quite as good — much less better — at any of it. This lineage has always had a reputation for difficulty, but Knightmare pushes that to the ragged edge, in terms of both its ridiculously convoluted environmental puzzles and the overpowered monsters you constantly face. Even the laddish staff of Amiga Format magazine, hardly a bastion of thoughtful design analyses, acknowledged that it “teeters on unplayably tough.” And even the modern blogger known as the CRPG Addict, whose name ought to say it all about his skill with these types of games, “question[s] whether it’s possible to win it without hints.”

Solo productions like this one, created in a vacuum, with little to no play-testing except by a designer who’s intimately familiar with every aspect of his game’s systems, often wound up getting the difficulty balance markedly wrong. Yet Knightmare is an extreme case even by the standards of that breed. If Dungeon Master is an extended explication of the benefits of careful level design, complete with lots of iterative feedback from real players, this game is a cautionary tale about the opposite extreme. While it was apparently successful in its day, there’s no reason for anyone who isn’t a masochist to revisit it in ours.

Eye of the Beholder‘s dependence on Dungeon Master is, as the CRPG Addict puts it, “so stark that you wonder why there weren’t lawsuits involved.” What it does bring new to the table is a whole lot more story and lore. Multi-page story dumps like this one practically contain more text than the entirety of Dungeon Master.

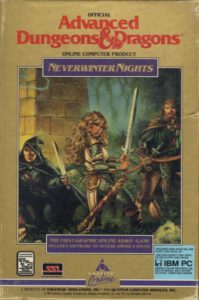

None of the three games I’ve just described was available in North America prior to 1992. Dungeon Master, having been created by an American developer, was for sale there, but only for the Amiga, Atari ST, and Apple IIGS, computers whose installed base in the country had never been overly large and whose star there dwindled rapidly after 1989. Thus the style of gameplay that Dungeon Master had introduced was either completely unknown or, at best, only vaguely known by most American gamers — this even as real-time blobbers had become a veritable gaming craze in Europe. But there was no reason to believe that American gamers wouldn’t take to them with the same enthusiasm as their European counterparts if they were only given the chance. There was simply a shortage of supply — and this, as any good capitalist knows, spells Opportunity.

The studio which finally walked through this open door is one I recently profiled in some detail: Westwood Associates. With a long background in real-time games already behind them, they were well-positioned to bring the real-time dungeon crawl to the American masses. Even better, thanks to a long-established relationship with the publisher SSI, they got the opportunity to do so under the biggest license in CRPGs, that of Dungeons & Dragons itself. With its larger development team and American-sized budget for art and sound, everything about Eye of the Beholder screamed hit, and upon its release in March of 1991 — more than half a year before Knightmare, actually — it didn’t disappoint.

It really is an impressive outing in many ways, the first example of its sub-genre that I can honestly imagine someone preferring to Dungeon Master. Granted, Westwood’s game lacks Dungeon Master‘s elegance: the turn-based Dungeons & Dragons rules are rather awkwardly kludged into real time; the environments still aren’t as organically interactive (amazingly, none of the heirs to Dungeon Master would ever quite live up to its example in this area); the controls can be a bit clumsy; the level design is nowhere near as fiendishly creative. But on the other hand, the level design isn’t pointlessly hard either, and the game is, literally and figuratively, a more colorful experience. In addition to the better graphics and sound, there’s far more story, steeped in the lore of the popular Dungeons & Dragons Forgotten Realms campaign setting. Personally, I still prefer Dungeon Master‘s minimalist aesthetic, as I do its cleaner rules set and superior level design. But then, I have no personal investment in the Forgotten Realms (or, for that matter, in elaborate fantasy world-building in general). Your mileage may vary.

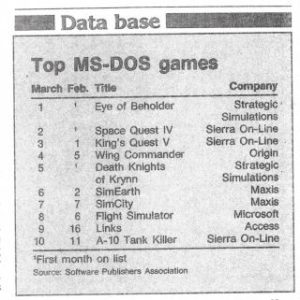

Whatever my or your opinion of it today, Eye of the Beholder hit American gamers like a revelation back in the day, and Europe too got to join the fun via a Westwood-developed Amiga port which shipped there within a few months of the MS-DOS original’s American debut. It topped sales charts in both places, becoming the first game of its type to actually outsell Dungeon Master. In fact, it became almost certainly the best-selling single example of a real-time blobber ever; between North America and Europe, total sales likely reached 250,000 copies or more, huge numbers at a time when 100,000 copies was the line that marked a major hit.

Following the success of Eye of the Beholder, the dam well and truly burst in the United States. Before the end of 1991, Westwood had cranked out an Eye of the Beholder II, which is larger and somewhat more difficult than its predecessor, but otherwise shares the same strengths and weaknesses. In 1993, their publisher SSI took over to make an Eye of the Beholder III in-house; it’s generally less well-thought-of than the first two games. Meanwhile Bloodwych and Captive got MS-DOS ports and arrived Stateside. Even FTL, whose attitude toward making new products can most generously be described as “relaxed,” finally managed to complete and release their long-rumored MS-DOS port of Dungeon Master — whereupon its dated graphics were, predictably if a little unfairly, compared unfavorably with the more spectacular audiovisuals of Eye of the Beholder in the American gaming press.

Another, somewhat more obscure title from this peak of the real-time blobber’s popularity was early 1992’s Black Crypt, the very first game from the American studio Raven Software, who would go on to a long and productive life. (As of this writing, they’re still active, having spent the last eight years or so making new entries in the Call of Duty franchise.) Although created by an American developer and published by the American Electronic Arts, one has to assume that Black Crypt was aimed primarily at European players, as it was made available only for the Amiga. Even in Europe, however, it failed to garner much attention in an increasingly saturated market; it looked a little better than Dungeon Master but not as good as Eye of the Beholder, and otherwise failed to stand out from the pack in terms of level design, interface, or mechanics.

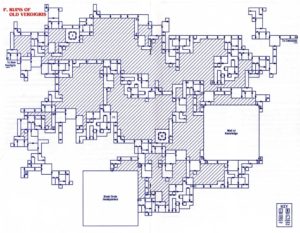

With, that is, one exception: Black Crypt did add an auto-map to the formula. Unfortunately, it was needlessly painful to access, being available only through a mana-draining wizard’s spell. Soon, though, Westwood would perfect the concept, as the real-time blobber entered the final phase of its existence as a gaming staple.

The auto-map in Lands of Lore looks pretty spectacular, as does almost every other part of the game.

Released in late 1993, Westwood’s Lands of Lore: The Throne of Chaos was an attempt to drag the now long-established real-time-blobber format into the multimedia age, while also transforming it into a more streamlined and accessible experience. It comes very, very close to realizing its ambitions, but is let down a bit by some poor design choices as it wears on.

Having gone their separate ways from SSI and from the strictures of the Dungeons & Dragons license, Westwood got to enjoy at last the same freedom which had spawned the easy elegance of Dungeon Master; they were free to, as Westwood’s Louis Castle would later put it, create cleaner rules that “worked within the context of a digital environment,” making extensive use of higher-math functions that could never have been implemented in a tabletop game. These designers, however, took their newfound freedom in a very different direction from the hardcore logistical and tactical challenge that was FTL’s game. “We’re trying to make our games more accessible to everybody,” said Westwood’s Brett Sperry at the time, “and we feel that the game consoles offer a clue as to where we should go in terms of interface. You don’t really have to read a manual for a lot of games, the entertainment and enjoyment is immediate.”

Lands of Lore places you in control of just two or three characters at a time, who come in and out of your party as the fairly linear story line dictates. The magic system is similarly condensed down to just seven spells. In place of the tactical maneuvering and environmental exploitation that marks combat within the more interactive dungeons of Dungeon Master is a simple but satisfying rock-paper-scissors approach: monsters are more or less vulnerable to different sorts of attacks, requiring you adjust your spells and equipment accordingly. And, most tellingly of all, an auto-map is always at your fingertips, even automatically annotating hidden switches and secret doors you might have overlooked in the first-person view.

Whether all of this results in a game that’s better than Dungeon Master is very much — if you’ll excuse the pun! — in the eye of the beholder. The auto-map alone changes the personality of the game almost enough to make it feel like the beginning of a different sub-genre entirely. Yet Lands of Lore has an undeniable charm all its own as a less taxing, more light-hearted sort of fantasy romp.

One thing at least is certain: at the time of its release, Lands of Lore was by far the most attractive blobber the world had yet seen. Abandoning the stilted medieval conceits of most CRPGs, its atmosphere is more fairy tale than Tolkien, full of bright cartoon-like tableaux rendered by veteran Hanna-Barbera and Disney animators. The music and voice acting in the CD-ROM version are superb, with none other than Patrick Stewart of Star Trek: The Next Generation fame acting as narrator.

Sadly, though, the charm does begin to evaporate somewhat as the game wears on. There’s an infamous one-level difficulty spike in the mid-game that’s all but guaranteed to run off the very newbies and casual players Westwood was trying to attract. Worse, the last 25 percent or so is clearly unfinished, a tedious slog through empty corridors with nothing of interest beyond hordes of overpowered monsters. When you get near the end and the game suddenly takes away the auto-map you’ve been relying on, you’re left wondering how the designers could have so completely lost all sense of the game they started out making. More so than any of the other games I’ve written about today, Lands of Lore: The Throne of Chaos, despite enjoying considerable commercial success which would lead to two sequels, feels like a missed opportunity.

Real-time blobbers would continue to appear for a couple more years after Lands of Lore. The last remotely notable examples are two 1995 releases: FTL’s ridiculously belated and rather unimaginative Dungeon Master II, which was widely and justifiably panned by reviewers; and Interplay’s years-in-the-making Stonekeep, which briefly dazzled some reviewers with such extraneous bells and whistles as an introductory cinematic that by at least one employee’s account cost ten times as much as the underwhelming game behind it. (If any other anecdote more cogently illustrates the sheer madness of the industry’s drunk-on-CD-ROM “interactive movie” period, I don’t know what it is.) Needless to say, neither game outdoes the original Dungeon Master where it counts.

At this point, then, we have to confront the place where the example I used in opening this article — that of interactive fiction and its urtext of Adventure — begins to break down when applied to the real-time blobber. Adventure, whatever its own merits, really was the launching pad for a whole universe of possibilities involving parsers and text. But the real-time blobber never did manage to transcend its own urtext, as is illustrated by the long shadow the latter has cast over this very article. None of the real-time blobbers that came after Dungeon Master was clearly better than it; arguably, none was ever quite as good. Why should this be?

Any answer to that question must, first of all, pay due homage to just how fully-realized Dungeon Master was as a game system, as well as to how tight its level designs were. It presented everyone who tried to follow it with one heck of a high bar to clear. Beyond that obvious fact, though, we must also consider the nature of the comparison with the text adventure, which at the end of the day is something of an apples-and-oranges proposition. The real-time blobber is a more strictly demarcated category than the text adventure; this is why we tend to talk about real-time blobbers as a sub-genre and text adventures as a genre. Perhaps there’s only so much you can do with wandering through grid-based dungeons, making maps, solving mechanical puzzles, and killing monsters. And perhaps Dungeon Master had already done it all about as well as it could be done, making everything that came after superfluous to all but the fanatics and the completists.

And why, you ask, had game developers largely stopped even trying to better Dungeon Master by the middle of the 1990s? [1]If one takes the really long view, they didn’t, at least not forever. In 2012, as part of the general retro-revival that has resurrected any number of dead sub-genres over the past decade, a studio known as Almost Human released Legend of Grimrock, the first significant commercial game of this type to be seen in many years. It got positive reviews, and sold well enough to spawn a sequel in 2014. I’m afraid I haven’t played either of them, and so can’t speak to the question of whether either or both of them finally managed the elusive trick of outdoing Dungeon Master. As it happens, there’s no mystery whatsoever about why the real-time blobber — or, for that matter, the blobber in general — disappeared from the marketplace. Even as the format was at its absolute peak of popularity in 1992, with Westwood’s Eye of the Beholder games selling like crazy and everything else rushing onto the bandwagon, an unassuming little outfit known as Blue Sky Productions gave notice to anyone who might have been paying attention that the blobber’s days were already numbered. This they did by taking a dungeon crawl off the grid. After that escalation in the gaming arms race, there was nothing for it but to finish whatever games in the old style were still in production and find a way to start making games in the new. Next time, then, we’ll turn our attention to the great leap forward that was Ultima Underworld.

(Sources: Computer Gaming World of April 1987, February 1991, June 1991, February 1992, March 1992, April 1992, November 1992, August 1993, November 1993, October 1994, October 1995, and February 1996; Amiga Format of December 1989, February 1992, March 1992, and May 1992; Questbusters of May 1991, March 1992, and December 1993; SynTax 22; The One of October 1990, August 1991, February 1992, October 1992, and February 1994. Online sources include Louis Castle’s interview for Soren Johnson’s Designer Notes podcast and Matt Barton’s interview with Peter Oliphant. Devotees of this sub-genre should also check out The CRPG Addict’s much more detailed takes on Bloodwych, Captive, Knightmare, Eye of the Beholder, Eye of the Beholder II, and Black Crypt.

The most playable of the games I’ve written about today, the Eye of the Beholder series and Lands of Lore: The Throne of Chaos, are available for purchase on GOG.com.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | If one takes the really long view, they didn’t, at least not forever. In 2012, as part of the general retro-revival that has resurrected any number of dead sub-genres over the past decade, a studio known as Almost Human released Legend of Grimrock, the first significant commercial game of this type to be seen in many years. It got positive reviews, and sold well enough to spawn a sequel in 2014. I’m afraid I haven’t played either of them, and so can’t speak to the question of whether either or both of them finally managed the elusive trick of outdoing Dungeon Master. |

|---|