If God exists, he must have a sense of humor, for why else would he have strewn so many practical jokes around his creation? Among them is the uncanny phenomenon of the talented writer who absolutely hates to write.

Mind you, I don’t mean just the usual challenges which afflict all of us architects of sentences and paragraphs. Even after all these years of writing these pieces for you, I’m still daunted every Monday morning to face a cursor blinking inscrutably at the top of a blank page, knowing as I do that that space has to be filled with a readable, well-constructed article by the time I knock off work the following Friday evening. In the end, though, that’s the sort of thing that any working writer knows how to get through, generally by simply starting to write something — anything, even if you’re pretty sure it’s the wrong thing. Then the sentences start to flow, and soon you’re trucking along nicely, almost as if the article has started to write itself. Whatever it gets wrong about itself can always be sorted out in revision and editing.

No, the kind of agony which proves that God must be a trickster is far more extreme than the kind I experience every week. It’s the sort of birth pangs suffered by Thomas Harris, the conjurer of everybody’s favorite serial killer Hannibal Lecter, every time he tries to write a new novel. Stephen King — an author who most definitely does not have any difficulty putting pen to paper — has described the process of writing as a “kind of torment” for his friend Harris, one which leaves him “writhing on the floor in frustration.” Small wonder that the man has produced just six relatively slim novels over a career spanning 50 years.

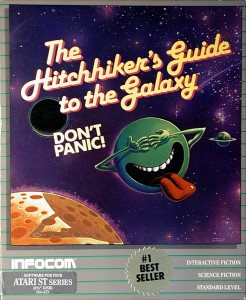

Another member of this strange club of prominent writers who hate to write is the Briton Douglas Adams, the mastermind of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Throughout his career, he was one of genre fiction’s most infuriating problem children, the bane of publishers, accountants, lawyers, and anyone else who ever had a stake in his actually sitting down and writing the things he had agreed to write. Given his druthers, he would prefer to sit in a warm bath, as he put it himself, enjoying the pleasant whooshing sound the deadlines made as they flew by just outside his window.

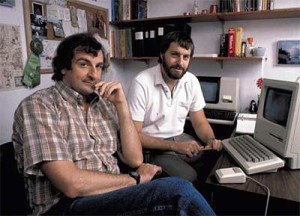

That said, Adams did manage to give outsiders at least the impression that he was a motivated, even driven writer over the first seven years or so of Hitchhiker’s, from 1978 to 1984. During that period, he scripted the twelve half-hour radio plays that were the foundation of the whole franchise, then turned them into four novels. He also assisted with a six-episode Hitchhiker’s television series, even co-designed a hit Hitchhiker’s text adventure with Steve Meretzky of Infocom. Adams may have hated the actual act of writing, but he very much liked the fortune and fame it brought him; the former because it allowed him to expand his collection of computers, stereos, guitars, and other high-tech gadgetry, the latter because it allowed him to expand the profile and diversity of guests whom he invited to his legendary dinner parties.

Still, what with fortune and fame having become something of a done deal by 1984, his instinctive aversion to the exercising of his greatest talent was by then beginning to set in in earnest. His publisher got the fourth Hitchhiker’s novel out of him that summer only by moving into a hotel suite with him, standing over his shoulder every day, and all but physically forcing him to write it. Steve Meretzky had to employ a similar tactic to get him to buckle down and create a design document for the Hitchhiker’s game, which joined the fourth novel that year to become one of the final artifacts of the franchise’s golden age.

Adams was just 32 years old at this point, as wealthy as he was beloved within science-fiction fandom. The world seemed to be his oyster. Yet he had developed a love-hate relationship with the property that had gotten him here. Adams had been reared on classic British comedy, from Lewis Carroll to P.G. Wodehouse, The Goon Show to Monty Python. He felt pigeonholed as the purveyor of goofy two-headed aliens and all that nonsense about the number 42. In So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish, the aforementioned fourth Hitchhiker’s novel, he’d tried to get away from some of that by keeping the proceedings on Earth, delivering what amounted to a magical-realist romantic comedy in lieu of another zany romp through outer space. But his existing fans hadn’t been overly pleased by the change of direction; they made it clear that they’d prefer more of the goofy aliens and the stuff about 42 in the next book, if it was all the same to him. “I was getting so bloody bored with Hitchhiker’s,” Adams said later. “I just didn’t have anything more to say in that context.” Even as he was feeling this way, though, he was trying very hard to get Hollywood to bite on a full-fledged, big-budget Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy feature film. Thus we have the principal paradox of his creative life: Hitchhiker’s was both the thing he most wanted to escape and his most cherished creative comfort blanket. After all, whatever else he did or didn’t do, he knew that he would always have Hitchhiker’s.

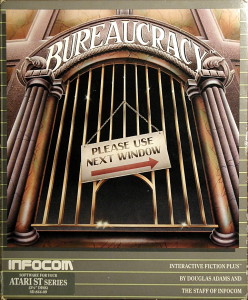

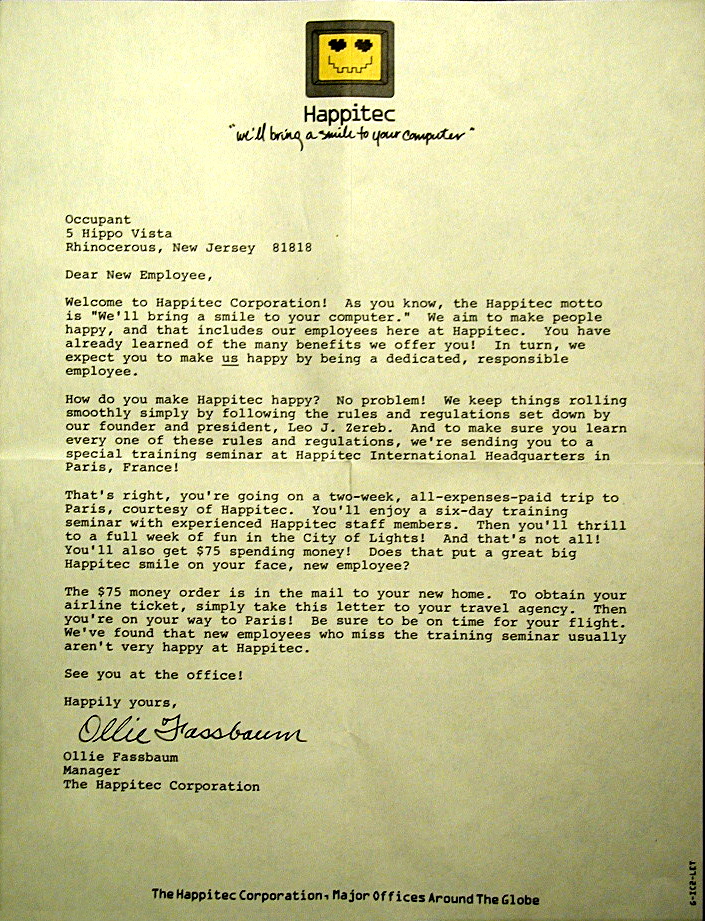

For a while, though, Adams did make a concerted attempt to do some things that were genuinely new. He pushed Infocom into agreeing to make a game with him that was not the direct sequel to the computerized Hitchhiker’s that they would have preferred to make. Bureaucracy was rather to be a present-day social satire about, well, bureaucracy, inspired by some slight difficulties Adams had once had getting his bank to acknowledge a change-of-address form. Meanwhile he sold to his book publishers a pair of as-yet unwritten non-Hitchhiker’s novels, with advances that came to about $4 million combined. They were to revolve around Dirk Gently, a “holistic detective” who solved crimes by relying upon “the fundamental interconnectedness of all things” in lieu of more conventional clues. “They will be recognizably me but radically different, at least from my point of view,” he said. “The story is based on here and now, but the explanation turns out to be science fiction.”

Adams’s enthusiasm for both projects was no doubt authentic when he conceived them, but it dissipated quickly when the time came to follow through, setting a pattern that would persist for the rest of his life. He went completely AWOL on Infocom, leaving them stuck with a project they had never really wanted in the first place. It was finally agreed that Adams’s best mate, a fellow writer named Michael Bywater, would come in and ghost-write Bureaucracy on his behalf. And this Bywater did, making a pretty good job of it, all things considered. (As for the proper Hitchhiker’s sequel which a struggling Infocom did want to make very badly: that never happened at all, although Adams caused consternation and confusion for a while on both side of the Atlantic by proposing that he and Infocom collaborate on it with a third party with which he had become enamored, the British text-adventure house Magnetic Scrolls. Perhaps fortunately under these too-many-cooks-in-the-kitchen circumstances, his follow-through here was no better than it had been on Bureaucracy, and the whole project died quietly after Infocom was shut down in 1989.)

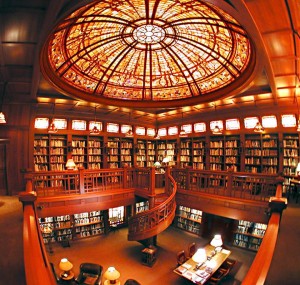

Dirk Gently was a stickier wicket, thanks to the amount of money that Adams’s publishers had already paid for the books. They got them out of him at last using the same method that had done the trick for So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish: locking him in a room with a minder and not letting him leave until he had produced a novel. Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency was published in 1987, its sequel The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul the following year. The books had their moments, but fell a little flat for most readers. In order to be fully realized, their ambitious philosophical conceits demanded an attention to plotting and construction that was not really compatible with being hammered out under duress in a couple of weeks. They left Adams’s old fans nonplussed in much the same way that So Long… had done, whilst failing to break him out of the science-fiction ghetto in which he felt trapped. Having satisfied his contractual obligations in that area, he would never complete another Dirk Gently novel.

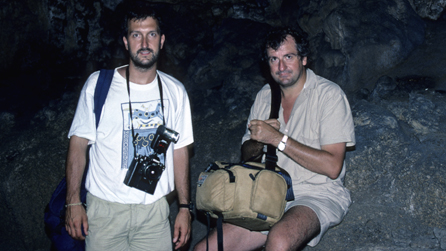

Then, the same year that the second Dirk Gently book was published, Adams stumbled into the most satisfying non-Hitchhiker’s project of his life. A few years earlier, during a jaunt to Madagascar, he had befriended a World Wildlife Federation zoologist named Mark Carwardine, who had ignited in him a passion for wildlife conservation. Now, the two hatched a scheme for a radio series and an accompanying book that would be about as different as they possibly could from the ones that had made Adams’s name: the odd couple would travel to exotic destinations in search of rare and endangered animal species and make a chronicle of what they witnessed and underwent. Carwardine would be the expert and the straight man, Adams the voice of the interested layperson and the comic relief. They would call the project Last Chance to See, because the species they would be seeking out might literally not exist anymore in just a few years. To his credit, Adams insisted that Carwardine be given an equal financial and creative stake. “We spent many evenings talking into the night,” remembers the latter. “I’d turn up with a list of possible endangered species, then we’d pore over a world map and talk about where we’d both like to go.”

They settled on the Komodo dragon of Indonesia, the Rodrigues flying fox of Mauritius, the baiji river dolphin of China, the Juan Fernández fur seal of South America’s Pacific coast, the mountain gorilla and northern white rhinoceros of East Africa, the kākāpō of New Zealand, and the Amazonian manatee of Brazil. Between July of 1988 and April of 1989, they traveled to all of these places — often as just the two of them, without any additional support staff, relying on Adams’s arsenal of gadgets to record the sights and especially the sounds. Adams came home 30 pounds lighter and thoroughly energized, eager to turn their adventures into six half-hour programs that were aired on BBC Radio later that year.

The book proved predictably more problematic. It was not completed on schedule, and was in a very real sense not even completed at all when it was wrenched away from its authors and published in 1990; the allegedly “finished” volume covers only five of the seven expeditions, and one of those in a notably more cursory manner than the others. Nevertheless, Adams found the project as a whole a far more enjoyable experience than the creation of his most recent novels had been. He had a partner to bounce ideas off of, making the business that much less lonely. And he wasn’t forced to invent any complicated plots from whole cloth, something for which he had arguably never been very well suited. He could just inhale his surroundings and exhale them again for the benefit of his readers, with a generous helping of the droll wit and the altogether unique perspective he could place on things. His descriptions of nature and animal life were often poignant and always delightful, as were those of the human societies he and Carwardine encountered. “Because I had an external and important subject to deal with,” mused Adams, “I didn’t feel any kind of compulsion to be funny the whole time — and oddly enough, a lot of people have said it’s the funniest book I’ve written.”

An example, on the subject of traffic in the fast-rising nation of China, which the pair visited just six months before the massacre on Tiananmen Square showed that its rise would take place on terms strictly dictated by the Communist Party:

Foreigners are not allowed to drive in China, and you can see why. The Chinese drive, or cycle, according to laws that are simply not apparent to an uninitiated observer, and I’m thinking not merely of the laws of the Highway Code; I’m thinking of the laws of physics. By the end of our stay in China, I had learnt to accept that if you are driving along a two-lane road behind another car or truck, and there are two vehicles speeding towards you, one of which is overtaking the other, the immediate response of your driver will be to also pull out and overtake. Somehow, magically, it all works out in the end.

What I could never get used to, however, was this situation: the vehicle in front of you is overtaking the vehicle in front of him, and your driver pulls out and overtakes the overtaking vehicle, just as three other vehicles are coming towards you performing exactly the same manoeuvre. Presumably Sir Isaac Newton has long ago been discredited as a bourgeois capitalist running-dog lackey.

Adams insisted to the end of his days that Last Chance to See was the best thing he had ever written, and I’m not at all sure that I disagree with him. On the contrary, I find myself wishing that he had continued down the trail it blazed, leaving the two-headed aliens behind in favor of becoming some combination of humorist, cultural critic, and popular-science writer. “I’m full of admiration for people who make science available to the intelligent layperson,” he said. “Understanding what you didn’t before is, to me, one of the greatest thrills.” Douglas Adams could easily have become one of those people whom he so admired. It seems to me that he could have excelled in that role, and might have been a happier, more satisfied man in it to boot. But it didn’t happen, for one simple reason: as well as taking a spot in the running for the title of best book he had ever written, Last Chance to See became the single worst-selling one. Adams:

Last Chance to See was a book I really wanted to promote as much as I could because the Earth’s endangered species is a huge topic to talk about. The thing I don’t like about doing promotion usually is that you have to sit there and whinge on about yourself. But here was a big issue I really wanted to talk about, and I was expecting to do the normal round of press, TV, and radio. But nobody was interested. They just said, “It isn’t what he normally does, so we’ll pass on this, thank you very much.” As a result, the book didn’t do very well. I had spent two years and £150,000 of my own money doing it. I thought it was the most important thing I’d ever done, and I couldn’t get anyone to pay any attention.

Now, we might say at this point that there was really nothing keeping Adams from doing more projects like Last Chance to See. Financially, he was already set for life, and it wasn’t as if his publishers were on the verge of dropping him. He could have accepted that addressing matters of existential importance aren’t always the best way to generate high sales, could have kept at it anyway. In time, perhaps he could have built a whole new audience and authorial niche for himself.

Yet all of that, while true enough on the face of it, fails to address just how difficult it is for anyone who has reached the top of the entertainment mountain to accept relegation to a base camp halfway down its slope. It’s the same phenomenon that today causes Adams’s musical hero and former dinner-party guest Paul McCartney, who is now more than 80 years old, to keep trying to score one more number-one hit instead of just making the music that pleases him. Once you’ve tasted mass adulation, modest success can have the same bitter tang as abject failure. There are artists who are so comfortable in their own skin, or in their own art, or in their own something, that this truism does not apply. But Douglas Adams, a deeply social creature who seemed to need the approbation of fans and peers as much as he needed food and drink, was not one of them.

So, he retreated to his own comfort zone and wrote another Hitchhiker’s novel. At first it was to be called Starship Titanic, but then it became Mostly Harmless. The choice to name it after one of the oldest running gags in the Hitchhiker’s series was in some ways indicative; this was to be very much a case of trotting out the old hits for the old fans. The actual writing turned into the usual protracted war between Adams’s publisher and the author himself, who counted as his allies in the cause of procrastination the many shiny objects that were available to distract a wealthy, intellectually curious social butterfly such as him. This time he had to be locked into a room with not only a handler from his publisher but his good friend Michael Bywater, who had, since doing Bureaucracy for Infocom, fallen into the role of Adams’s go-to ghostwriter for many of the contracts he signed and failed to follow through on. Confronted with the circumstances of its creation, one is immediately tempted to suspect that substantial chunks of Mostly Harmless were actually Bywater’s work. By way of further circumstantial evidence, we might note that some of the human warmth that marked the first four Hitchhiker’s novels is gone, replaced by a meaner, archer style of humor that smacks more of Bywater than the Adams of earlier years.

It’s a strange novel — not a very good one, but kind of a fascinating one nonetheless. Carl Jung would have had a field day with it as a reflection of its author’s tortured relationship to the trans-media franchise he had spawned. There’s a petulant, begrudging air to the thing, right up until it ends in the mother of all apocalypses, as if Adams was trying to wreck his most famous creation so thoroughly that he would never, ever be able to heed its siren call again. “The only way we could persuade Douglas to finish Mostly Harmless,” says Michael Bywater, “was [to] offer him several convincing scenarios by which he could blow up not only this Earth but all the Earths that may possibly exist in parallel universes.” That was to be that, said Adams. No more Hitchhiker’s, ever; he had written the franchise into a black hole from which it could never emerge. Which wasn’t really true at all, of course. He would always be able to find some way to bring the multidimensional Earth back in the future, should he decide to, just as he had once brought the uni-dimensional Earth back from its destruction in the very first novel. Such is the advantage of being god of your own private multiverse. Indeed, there are signs that Adams was already having second thoughts before he even allowed Mostly Harmless to be sent to the printer. At the last minute, he sprinkled a few hints into the text that the series’s hero Arthur Dent may in fact have survived the apocalypse. It never hurts to hedge your bets.

Published in October of 1992, Mostly Harmless sold better than Last Chance to See or the Dirk Gently novels, but not as well as the golden-age Hitchhiker’s books. Even the series’s most zealous fans could smell the ennui that fairly wafted up from its pages. Nevertheless, they would have been shocked if you had told them that Douglas Adams, still only 40 years old, would never finish another book.

The next several years were the least professionally productive of Adams’s adult life to date. This wasn’t necessarily a bad thing; there is, after all, more to life than one’s career. He had finally married his longtime off-and-on romantic partner Jane Belson in 1991, and in 1994, when the husband’s age was a thoroughly appropriate 42, the couple had their first and only child. When not doting on his baby daughter Polly, Adams amused himself with his parties and his hobbies, which mostly involved his beloved Apple Macintosh computers and, especially, music. He amassed what he believed to be the largest collection of left-handed guitars in the world. His friend David Gilmour gave him his best birthday gift ever when he allowed him to come onstage and play one of those guitars with Pink Floyd for one song on their final tour. Adams also performed as one half of an acoustic duo at an American Booksellers’ Association Conference; the duo’s other half was the author Ken Follett. He even considered trying to make an album of his own: “It will basically be something very similar to Sgt. Pepper, I should think.” Let it never be said that Douglas Adams didn’t aim high in his flights of fancy…

With Adams thus absent from the literary scene, his position as genre fiction’s premiere humorist was seized by Terry Pratchett, whose first Discworld novels of the mid-1980s might be not unfairly described as an attempt to ape Adams in a fantasy rather than a science-fiction setting, but who had long since come into his own. Pratchett evinced none of Adams’s fear and loathing of the actual act of writing, averaging one new Discworld novel every nine months throughout the 1990s. By way of a reward for his productivity, his wit, and his boundless willingness to take his signature series in unexpected new directions, he became the most commercially successful single British author of any sort of the entire decade.

A new generation of younger readers adored Discworld but had little if any familiarity with Hitchhiker’s. While Pratchett basked in entire conventions devoted solely to himself and his books, Adams sometimes failed to muster an audience of more than twenty when he did make a public appearance — a sad contrast to his book signings of the early 1980s, when his fans had lined up by the thousands for a quick signature and a handshake. A serialized graphic-novel adaption of Hitchhiker’s, published by DC Comics, was greeted with a collective shrug, averaging about 20,000 copies sold per issue, far below projections. Despite all this clear evidence, Adams, isolated in his bubble of rock stars and lavish parties, seemed to believe he still had the same profile he’d had back in 1983. That belief — or delusion — became the original sin of his next major creative project, which would sadly turn out to be the very last one of his life.

The genesis of Douglas Adams’s second or third computer game — depending on what you make of Bureaucracy — dates to late 1995, when he became infatuated with a nascent collective of filmmakers and technologists who called themselves The Digital Village. The artist’s colony cum corporation was the brainchild of Robbie Stamp, a former producer for Britain’s Central Television: “I was one of a then-young group of executives looking at the effects of digital technology on traditional media businesses. I felt there were some exciting possibilities opening up, in terms of people who could understand what it would mean to develop an idea or a brand across a variety of different platforms and channels.” Stamp insists that he wasn’t actively fishing for money when he described his ideas one day to Adams, who happened to be a friend of a friend of his named Richard Creasey. He was therefore flabbergasted when Adams turned to him and asked, “What would it take to buy a stake?” But he was quick on his feet; he named a figure without missing a beat. “I’m in,” said Adams. And that was that. Creasey, who had been Stamp’s boss at Central Television, agreed to come aboard as well, and the trio of co-founders was in place.

One senses that Adams was desperate to find a creative outlet that was less dilettantish than his musical endeavors but also less torturous than being locked into a room and ordered to write a book.

When I started out, I worked on radio, I worked on TV, I worked onstage. I enjoyed and experimented with different media, working with people and, wherever possible, fiddling with bits of equipment. Then I accidentally wrote a bestselling novel, and the consequence was that I had to write another and then another. After a decade or so of this, I became a little crazed at the thought of spending my entire working life in a room by myself typing. Hence The Digital Village.

The logic was sound enough when considered in the light of the kind of personality Adams was; certainly one of the reasons Last Chance to See had gone so well had been the presence of an equal partner to keep him engaged.

Still, the fact remained that it could be a little hard to figure out what The Digital Village was really supposed to be. Rejecting one of the hottest buzzwords of the age, Adams insisted that it was to be a “multiple media” company, not a “multimedia” one: “We’re producing CD-ROMs and other digital and online projects, but we’re also committed to working in traditional forms of media.” To any seasoned business analyst, that refusal to focus must have sounded like a recipe for trouble; “do one thing very, very well” is generally a better recipe for success in business than the jack-of-all-trades approach. And as it transpired, The Digital Village would not prove an exception to this rule.

Their first idea was to produce a series of science documentaries called Life, the Universe, and Evolution, a riff on the title of the third Hitchhiker’s novel; that scheme fell through when they couldn’t find a television channel that was all that interested in airing it. Their next idea was to set up The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Internet, a search engine to compete with the current king of Web searching Yahoo!; that scheme fell through when they realized that they had neither the financial resources nor the technical expertise to pull it off. And so on and so on. “We were going to be involved in documentaries, feature films, and the Internet,” says Richard Creasey regretfully. “And bit by bit they all went away. Bit by bit, we went down one avenue which was, in the nicest possible way, a disaster.”

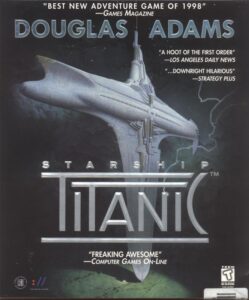

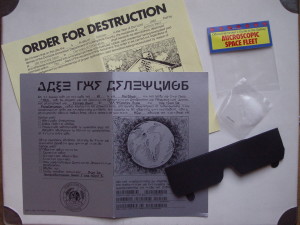

That avenue was a multimedia adventure game, a project which would come to consume The Digital Village in more ways than one. It was embarked upon for the very simple reason that it was the only one of the founders’ ideas for which they could find adequate investment capital. At the time, the culture was living through an odd echo of the “bookware” scene of the mid-1980s, of which Infocom’s Hitchhiker’s game has gone down in history as the most iconic example. A lot of big players in traditional media were once again jumping onto the computing bandwagon with more money than sense. Instead of text and text parsers, however, Bookware 2.0 was fueled by great piles of pictures and video, sound and music, with a thin skein of interactivity to join it all together. Circa 1984, the print-publishing giant Simon & Schuster had tried very, very hard to buy Infocom, a purchase that would have given them the Hitchhiker’s game that was then in the offing. Now, twelve years later, they finally got their consolation prize, when Douglas Adams agreed to make a game just for them. All they had to do was give him a few million dollars, an order of magnitude more than Infocom had had to put into their Hitchhiker’s.

The game was to be called Starship Titanic. Like perhaps too many Adams brainstorms of these latter days, it was a product of recycling. As we’ve already seen, the name had once been earmarked for the novel that became Mostly Harmless, but even then it hadn’t been new. No, it dated all the way back to the 1982 Hitchhiker’s novel Life, the Universe, and Everything, which had told in one of its countless digressions of a “majestic and luxurious cruise liner” equipped with a flawed prototype of an Infinite Improbability Drive, such that on its maiden voyage it had undergone “a sudden and gratuitous total existence failure.” In the game, the vessel would crash through the roof of the player’s ordinary earthly home; what could be more improbable than that? Then the player would be sucked aboard and tasked with repairing the ship’s many wildly, bizarrely malfunctioning systems and getting it warping through hyperspace on the straight and narrow once again. Whether Starship Titanic exists in the same universe — or rather multiverse — as Hitchhiker’s is something of an open question. Adams was never overly concerned with such fussy details of canon; his most devoted fans, who very much are, have dutifully inserted it into their Hitchhiker’s wikis and source books on the basis of that brief mention in Life, the Universe, and Everything.

Adams was often taken by a fit of almost manic enthusiasm when he first conceived of a new project, and this was definitely true of Starship Titanic. He envisioned another trans-media property to outdo even Hitchhiker’s in its prime. Naturally, there would need to be a Starship Titanic novel to accompany the game. Going much further, Adams pictured his new franchise fulfilling at last his fondest unrequited dream for Hitchhiker’s. “I’m not in a position to make any sort of formal announcement,” he told the press cagily, “but I very much hope that it will have a future as a movie as well.” There is no indication that any of the top-secret Hollywood negotiations he was not-so-subtly hinting at here ever took place.

In their stead, just about everything that could possibly go wrong with the whole enterprise did so. It became a veritable factory for resentments and bad feelings. Robbie Stamp and Richard Creasey, who didn’t play games at all and weren’t much interested in them, were understandably unhappy at seeing their upstart new-media collective become The Douglas Adams Computer Games Company. This created massive dysfunction in the management ranks.

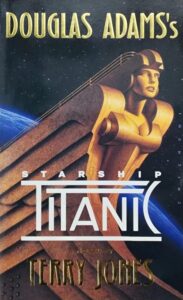

Predictably enough, Adams brought in Michael Bywater to help him when his progress on the game’s script stalled out. Indeed, just as is the case with Mostly Harmless, it’s difficult to say where Douglas Adams stops and Michael Bywater begins in the finished product. In partial return for his services, Bywater believed that his friend implicitly or explicitly promised that he could write and for once put his own name onto the Starship Titanic novel. But this didn’t happen in the end. Instead Adams sourced it out to Robert Sheckley, his favorite old-school science-fiction writer, who was in hard financial straits and could use the work. When Sheckley repaid his charity with a manuscript that was so bad as to be unpublishable, Adams bypassed Bywater yet again, giving the contract to another friend, the Monty Python alum Terry Jones, who also did some voice acting in the game. Bywater was incensed by this demonstration of exactly where he ranked in Adams’s entourage; it seemed he was good enough to become the great author’s emergency ghostwriter whenever his endemic laziness got him into a jam, but not worthy of receiving credit as a full-fledged collaborator. The two parted acrimoniously; the friendship, one of the longest and closest in each man’s life, would never be fully mended.

And all over a novel which, under Jones’s stewardship, came out tortuously, exhaustingly unfunny, the very essence of trying way too hard.

“Where is Leovinus?” demanded the Gat of Blerontis, Chief Quantity Surveyor of the entire North Eastern Gas District of the planet of Blerontin. “No! I do not want another bloody fish-paste sandwich!”

He did not exactly use the word “bloody” because it did not exist in the Blerontin language. The word he used could be more literally translated as “similar in size to the left earlobe,” but the meaning was much closer to “bloody.” Nor did he actually use the phrase “fish paste,” since fish do not exist on Blerontin in the form in which we would understand them to be fish. But when one is translating from a language used by a civilisation of which we know nothing, located as far away as the centre of the galaxy, one has to approximate. Similarly, the Gat of Blerontis was not exactly a “Quantity Surveyor,” and certainly the term “North Eastern Gas District” gives no idea at all about the magnificence and grandeur of his position. Look, perhaps I’d better start again…

Oh, my. Yes, Terry, perhaps you should. Whatever else you can say about Michael Bywater, he at least knew how to ape Douglas Adams without drenching the page in flop sweat.

The novel came out in December of 1997, a few months before the game, sporting on its cover the baffling descriptor Douglas Adams’s Starship Titanic by Terry Jones. In a clear sign that Bookware 2.0 was already fading into history alongside its equally short-lived predecessor, Simon & Schuster gave it virtually no promotion. Those critics who deigned to notice it at all savaged it for being exactly what it was, a slavishly belabored third-party imitation of a set of tired tropes. Adams and Jones did a short, dispiriting British book tour together, during which they were greeted with half-empty halls and bookstores; those fans who did show up were more interested in talking about the good old days of Hitchhiker’s and Monty Python than Starship Titanic. It was not a positive omen for the game.

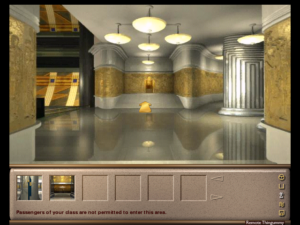

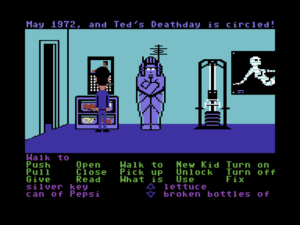

At first glance, said game appears to be a typical product of the multimedia-computing boom, when lots and lots of people with a lot of half-baked highfalutin ideas about the necessary future of games suddenly rushed to start making them, without ever talking to any of the people who had already been making them for years or bothering to try to find out what the ingredients of a good, playable game might in fact be. Once you spend just a little bit of time with Starship Titanic, however, you begin to realize that this rush to stereotype it has done it a disservice. It is in reality uniquely awful.

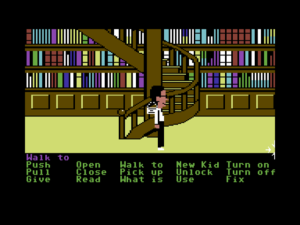

From Myst and its many clones, it takes its first-person perspective and its system of navigation, in which you jump between static, pre-rendered nodes in a larger contiguous space. That approach is always a little unsatisfactory even at its best — what you really want to be doing is wandering through a seamless world, not hopping between nodes — but Starship Titanic manages to turn the usual Mysty frustrations into a Gordian Knot of agony. The amount of rotation you get when you click on the side of the screen to turn the view is wildly inconsistent from node to node and turn to turn, even as the views themselves seem deliberately chosen to be as confusing as possible. This is the sort of game where you can find yourself stuck for hours because you failed to spot… no, not some tiny little smear of pixels on the floor representing some obscure object, but an entire door that can only be seen from one fiddly angle. Navigating the spaceship is the Mount Everest of fake difficulties — i.e., difficulties that anyone who was actually in this environment would not be having.

Myst clones usually balance their intrinsic navigational challenges with puzzles that are quite rigorously logical, being most typically of the mechanical stripe: experiment with the machinery to deduce what each button and lever does, then apply the knowledge you gain to accomplish some task. But not Starship Titanic. It relies on the sort of moon logic that’s more typical of the other major strand of 1990s adventure game, those that play out from a third-person perspective and foreground plot, character interaction, and the player’s inventory of objects to a much greater degree. Beyond a certain point, only the “try everything on everything” method will get you anywhere in Starship Titanic. This is made even more laborious by an over-baked interface in which every action takes way more clicks than it ought to. Like everything else about the game, the interface too is wildly inconsistent; sometimes you can interact with things in one way, sometimes in another, with no rhyme or reason separating the two. You just have to try everything every which way, and maybe at some point something works.

Having come this far, but still not satisfied with merely having combined the very worst aspects of the two major branches of contemporary adventure games, Douglas Adams looked to the past for more depths to plumb. At his insistence, Starship Titanic includes, of all things, a text parser — a text parser just as balky and obtuse as most of the ones from companies not named Infocom back in the early 1980s. It rears its ugly head when you attempt to converse with the robots who are the ship’s only other inhabitants. The idea is that you can type what you want to say to them in natural language, thereby to have real conversations with them. Alas, the end result is more Eliza than ChatGPT. The Digital Village claimed to have recorded sixteen hours of voiced responses to your conversational sallies and inquiries. This sounds impressive — until you start to think about what it means to try to pack coherent responses to literally anything in the world the player might possibly say to a dozen or so possible interlocutors into that span of time. What you get out on the other end is lots and lots of variations on “I don’t understand that,” when you’re not being blatantly misunderstood by a parser that relies on dodgy pattern matching rather than any thoroughgoing analysis of sentence structure. Nothing illustrates more cogently how misconceived and amateurish this whole project was; these people were wasting time on this nonsense when the core game was still unplayable. Adams, who had been widely praised for stretching the parser in unusual, slightly postmodern directions in Infocom’s Hitchhiker’s game, clearly wanted to recapture that moment here. But he had no Steve Meretzky with him this time — no one at all who truly understood game design — to corral his flights of imagination and channel them into something achievable and fun. It’s a little sad to see him so mired in an unrecoverable past.

But if the parser is weird and sad, the weirdest and saddest thing of all about Starship Titanic is how thoroughly unfunny it is. Even a compromised, dashed-off Adams novel like Mostly Harmless still has moments which can make you smile, which remind you that, yes, this is Douglas Adams you’re reading. Starship Titanic, on the other hand, is comprehensively tired and tiring, boiling Adams’s previous oeuvre down to its tritest banalities — all goofy robots and aliens, without the edge of satire and the cock-eyed insights about the human condition that mark Hitchhiker’s. Was Adams losing his touch as a humorist? Or did his own voice just get lost amidst those of dozens of other people trying to learn on the fly how to make a computer game? It’s impossible to say. It is pretty clear, however, that he had one foot out the door of the project long before it was finished. “In the end, I think he felt quite distanced from it,” says Robbie Stamp of his partner. That sentiment applied equally to all three co-founders of the The Digital Village, who couldn’t fully work out just how their dreams and schemes had landed them here. In a very real way, no one involved with Starship Titanic actually wanted to make it.

I suppose it’s every critic’s duty to say something kind about even the worst of games. In that spirit, I’ll note that Starship Titanic does look very nice, with an Art Deco aesthetic that reminds me slightly of a far superior adventure game set aboard a moving vehicle, Jordan Mechner’s The Last Express. If nothing else, this demonstrates that The Digital Village knew where to find talented visual artists, and that they were sophisticated enough to choose a look for their game and stick to it. Then, too, the voice cast the creators recruited was to die for, including not only Terry Jones and Douglas Adams himself but even John Cleese, who had previously answered every inquiry about appearing in a game with some variation of “Fuck off! I don’t do games!” The music was provided by Wix Wickens, the keyboardist and musical director for Paul McCartney’s touring band. What a pity that no one from The Digital Village had a clue what to do with their pile of stellar audiovisual assets. Games were “an area about which we knew nothing,” admits Richard Creasey. That went as much for Douglas Adams as any of the rest of them; as Starship Titanic’s anachronistic parser so painfully showed, his picture of the ludic state of the art was more than a decade out of date.

Begun in May of 1996, Starship Titanic shipped in April of 1998, more than six months behind schedule. Rather bizarrely, no one involved seems ever to have considered explicitly branding it as a Hitchhiker’s game, a move that would surely have increased its commercial potential at least somewhat. (There was no legal impediment to doing so; Adams owned the Hitchhiker’s franchise outright.) Adams believed that his name on the box alone could make it a hit. Some of those around him were more dubious. “I think it was a harsh reality,” says Robbie Stamp, “that Douglas hadn’t been seen to figure big financially by anyone for a little while.” But no one was eager to have that conversation with him at the time.

So, Starship Titanic was sent out to greet an unforgiving world as its own, self-contained thing, and promptly stiffed. Even the fortuitous release the previous December of James Cameron’s blockbuster film Titanic, which had elevated another adventure game of otherwise modest commercial prospects to million-seller status, couldn’t save this one. Many of the gaming magazines and websites didn’t bother to review it at all, so 1996 did it feel in a brave new world where first-person shooters and real-time strategies were all the rage. Of those that did, GameSpot’s faint praise is typically damning: “All in all, Starship Titanic is an enjoyable tribute to an older era of adventure gaming. It feels a bit empty at times, but Douglas Adams fans and text-adventurers will undoubtedly be able to look past its shortcomings.” This is your father’s computer game, in other words. But leave it to Charles Ardai of Computer Gaming World magazine to deliver a zinger worthy of Adams himself: he called Starship Titanic a “Myst opportunity.”

One of the great ironies of this period is that, at the same time Douglas Adams was making a bad science-fiction-comedy adventure game, his erstwhile Infocom partner Steve Meretzky was making one of his own, called The Space Bar. Released the summer before Starship Titanic, it stiffed just as horribly. Perhaps if the two had found a way to reconnect and combine their efforts, they could have sparked the old magic once again.

As it was, though, Adams was badly shaken by the failure of Starship Titanic, the first creative product with his name on it to outright lose its backers a large sum of money. “Douglas’s fight had gone out of him,” says Richard Creasey. Adams found a measure of solace in blaming the audience — never an auspicious posture for any creator to adopt, but needs must. “What we decided to do in this game was go for the non-psychopath sector of the market,” he said. “And that was a little hubristic because there really isn’t a non-psychopath sector of the market.” The 1.5 million people who were buying the non-violent Myst sequel Riven at the time might have begged to differ.

Luckily, Adams had something new to be excited about: in late 1997, he had signed a development deal with Disney for a “substantial” sum of money — a deal that would, if all went well, finally lead to his long-sought Hitchhiker’s film. Wanting to be close to the action and feeling that he needed a change of scenery, he opted to pull up stakes from the Islington borough of London where he had lived since 1980 and move with his family to Los Angeles. A starry-eyed Adams was now nursing dreams of Hugh Laurie or Hugh Grant as Arthur Dent, Jim Carrey as the two-headed Zaphod Beeblebrox.

The rump of The Digital Village which he left behind morphed into h2g2, an online compendium of user-generated knowledge, an actually extant version of the fictional Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. If you’re thinking that sounds an awful lot like Wikipedia, you’re right; the latter site, which was launched two years after h2g2 made its debut in 1999, has thoroughly superseded it today. In its day, though, h2g2 was a genuinely visionary endeavor, an early taste of the more dynamic, interactive Web 2.0 that would mark the new millennium. Adams anticipated the way we live our digital lives today to an almost unnerving degree.

The real change takes place [with] mobile computing, and that is beginning to arrive now. We’re beginning to get Internet access on mobile phones and personal digital assistants. That creates a sea change because suddenly people will be able to get information that is appropriate to where they are and who they are — standing outside the cinema or a restaurant or waiting for a bus or a plane. Or sitting having a cup of coffee at a café. With h2g2, you can look up where you are at that moment to see what it says, and if the information is not there you can add it yourself. For example, a remark about the coffee you’re drinking or a comment that the waiter is very rude.

When not setting the agenda with prescient insights like these — he played little day-to-day role in the running of h2g2 — Adams wrote several drafts of a Hitchhiker’s screenplay and knocked on a lot of doors in Hollywood inquiring about the state of his movie, only to be politely put off again and again. Slowly he learned the hard lesson that many a similarly starry-eyed creator had been forced to learn before him: that open-ended deals like the one he had signed with Disney progress — or don’t progress — on their own inscrutable timeline.

In the meanwhile, he continued to host parties — more lavish ones than ever now after his Disney windfall — and continued being a wonderful father to his daughter. He found receptive audiences on the TED Talk circuit, full of people who were more interested in hearing his Big Ideas about science and technology than quizzing him on the minutiae of Hitchhiker’s. Anyone who asked him what else he was working on at any given moment was guaranteed to be peppered with at least half a dozen excited and exciting responses, from books to films, games to television, websites to radio, even as anyone who knew him well knew that none of them were likely to amount to much. Be that as it may, he seemed more or less happy when he wasn’t brooding over Disney’s lack of follow-through, which some might be tempted to interpret as karmic retribution for the travails he had put so many publishers and editors through over the years with his own lack of same. “I love the sense of space and the can-do attitude of Americans,” he said of his new home. “It’s a good place to bring up children.” Embracing the California lifestyle with enthusiasm, he lost weight, cut back on his alcohol consumption, and tried to give up cigarettes.

By early 2001, it looked like there was finally some movement on the Hitchhiker’s movie front. Director Jay Roach, hot off the success of Austin Powers and Meet the Parents, was very keen on it, enough so that Adams was motivated to revise the screenplay yet again to his specifications. On May 11 of that year, not long after submitting these revisions, Douglas Adams went to his local gym for his regular workout. After twenty minutes on the treadmill, he paused for a breather before moving on to stomach crunches. Seconds after sitting down on a bench, he collapsed to the floor, dead. Falling victim to another cosmic joke as tragically piquant as the brilliant writer who hates to write, his heart simply stopped beating, for no good reason that any coroner could divine. He was just 49 years old.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Hitchhiker: A Biography of Douglas Adams by M.J. Simpson, Wish You Were Here: The Official Biography of Douglas Adams by Nick Webb, The Frood: The Authorised and Very Official History of Douglas Adams & The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Jem Roberts, The Ultimate Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams, Last Chance to See by Douglas Adams and Mark Carwardine, and Douglas Adams’s Starship Titanic by Terry Jones; Computer Gaming World of September 1998.

Online sources include Gamespot’s vintage review of Starship Titanic, an AV Club interview with Adams from January of 1998, “The Making of Starship Titanic“ from Adams’s website, The Digital Village’s website (yes, it still exists), and a Guardian feature on Thomas Harris.

Starship Titanic is available for digital purchase on GOG.com.