One American writer said to me, “Your books will never sell in America because you can’t hear the elves sing. Americans go in for fantasy books where you can hear the elves sing.”

I would like that put on my gravestone: “At least you can say that in Pratchett’s books, the bloody elves never sang!”

— Terry Pratchett

Two arguments are commonly trotted out for the genre literature of the fantastic as actually or potentially something more than mere escapism. One, which applies only to the science-fiction side of the science-fiction/fantasy divide, claims that it can be a form of useful social prognostication. By observing the trends of the current day, the writer can extrapolate where we are likely to end up in the future and present it vividly on the page, whether as a prophecy or a warning. Granted, science fiction’s record of prediction is not particularly good; the writers of just a handful of decades ago almost all believed we would have settled Mars by now, while vanishingly few of them imagined anything like the modern Internet. Still, if you believe that a society’s hopes and fears for the future say a lot about its present, there is a certain sociological value even in the failed prognostications. (Indeed, the academic critic Farah Mendlesohn goes so far as the claim that much classic science fiction is “a sense of wonder combined with [a] presentism” which only masquerades as futurism.)

But it’s the other argument for fantastic literature’s enduring worth that I find most convincing: by transporting some of our most fraught current problems and conflicts into another, less familiar context, we can examine them in a fresh light. Many of us have thought at one time or another how weird our ceaselessly squabbling planet must look to any aliens who happen to stumble across it, what with all the trivialities we continue to fight and kill one another over and the looming existential threats we continue to leave woefully under-addressed. Not only science-fiction but also fantasy literature can literally or figuratively put us in the shoes of those aliens (assuming they wear shoes), allowing us to examine ideas and values with fresh eyes, less cultural baggage, and less of a knee-jerk response.

From the mid-1980s until the mid-2010s, the writer who made perhaps the most consistent case of all for fantasy literature as a laboratory of ideas that are eminently relevant to the real world was Terry Pratchett. And if that didn’t do it for you — well, he really was quite funny to boot.

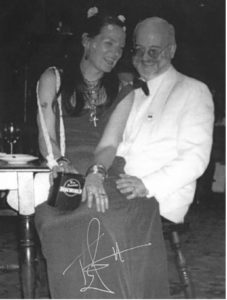

Terry and Lyn Pratchett on their wedding day in 1968. On their honeymoon, Terry would grow the beard which he would sport for the rest of his life.

Terence David John Pratchett was born on April 28, 1948, in a rural village in Buckinghamshire, England. The only child of an auto mechanic and a secretary, he grew up in a house with no indoor toilet, no hot water, and no electricity. But a less economically advantaged upbringing does not automatically mean a bad one: young Terry spent his days rambling over the same green and pleasant English landscapes that had inspired J.R.R. Tolkien’s Shire, while in the evenings he read books by the light of an oil lamp. Amidst it all, he absorbed his parent’s commonsense belief in what the British call “common decency.” He was not a member of the social class that typically went to university, and this was never regarded as a serious option for him by his teachers or his parents even when he showed an unusual talent for reading and writing. Instead he walked into the office of his local newspaper at the age of seventeen and asked to become an apprentice journalist.

And so he embarked on what his peers and his betters would have considered a perfectly respectable if not quite exciting life for one of his social station. He spent a decade and a half working as a small-town beat reporter, columnist, and editor, before switching to a less demanding job with the civil service, as a press officer for the Central Electricity Generating Board. Betwixt and between his professional accomplishments, he married his first-ever girlfriend before he turned 21, fathered a daughter with her, and lived with his family in a tidy little cottage no better nor worse than a thousand others in its corner of England.

He had just one obvious eccentricity: he loved science-fiction and especially fantasy literature, and wrote some of it himself on and off. By 1982, he had published three competent if derivative novels, in small print runs with the help of a friend with the requisite connections. Yet his closest brush with real literary fame remained the letter he had received from J.R.R. Tolkien back in 1968, in response to a piece of fan mail he had sent to the aging Oxford don.

By this point, fantasy literature had well and truly come into its own, thanks to the ongoing popularity of Tolkien and an odd new tabletop game called Dungeons & Dragons that was reaching Britain from American shores. Bookstore shelves were filling up with fat, multi-volume epics from other authors like Terry Brooks and Raymond E. Feist, who were all straining so hard to be Tolkien that one could almost hear them huffing and puffing in the background as one turned the pages. But Terry Pratchett, despite loving Tolkien so much himself that he claimed to have read The Lord of the Rings at least once per year ever since discovering it at the age of thirteen, wasn’t at all sure that such slavish imitation was the best form of flattery. He decided to write a book making fun of the trend.

To be sure, it wasn’t the highest-hanging of fruit as targets of satire went; these ponderous, interminable, oh-so-serious tomes could almost be read as parodies of Tolkien already, albeit inadvertent ones. Nor was Pratchett the first writer to have the idea; as early as 1969, when “Frodo Lives!” could be found emblazoned on the walls of the Boston subway alongside “Clapton is God!”, a pair of Harvard students had published a satire of the counterculture’s favorite fantasist called Bored of the Rings. But thankfully, Pratchett had a cleverer approach in mind than their frat-boy slapstick.

The germ of it dated back to 1978, and a column he had written poking gentle fun at the Star Wars craze. His long experience as a reporter had taught him that the proverbial little people of our own or, presumably, any other world are more exercised by mundane concerns than epic adventure. Applying this lesson to Star Wars, he offered up a science-fictional take on the banality of evil, in the form of the chief personnel officer on the Death Star, fielding complaints about the lousy coffee in the canteen, parrying worries over all those droids that were taking so many human Stormtroopers’ jobs.

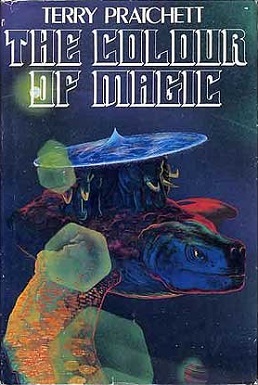

Now, taking the same approach over to a world of epic fantasy, Pratchett considered what the little people there would be doing while the heroes were prattling on about Courage and Sacrifice and all the rest of that rot. The star of this “realist fantasy” — a term invented by Pratchett’s biographer Marc Burrows — would be an inept wizard named Rincewind, a perpetual graduate student at a school of magic called Unseen University. His greatest talent would be that of shirking danger and, when push came to shove, simply running away as fast as his knobby-kneed little legs could carry him. For, as Burrows writes, “when faced with violence and the threat of death, most people do not throw themselves honourably into the fray: they get the hell out of there. Rincewind is the very distillation of Pratchett’s central premise of treating a fantasy world literally.”

The fantasy world in question is, as Pratchett wrote at the beginning of the book and then proceeded to spend the next 30 years patiently repeating at the beginning of every interview he gave to the mainstream media, a flat disc borne on the backs of four giant elephants, who in turn stand on the back of a giant turtle swimming through the outer space of “a distant and secondhand set of dimensions, in an astral plane that was never meant to fly”; the premise displays Pratchett’s lifelong interest in astronomy and Hindu cosmology, as well as his love of dreadful puns. The chronically exasperated Rincewind and his unlikely companion, a naïve tourist named Twoflower whose insatiable curiosity causes him to run toward every danger from which Rincewind wants to run away, spend the book traveling across the Discworld and getting caught up in a series of comic misadventures that expose countless inviolate fantasy clichés to the cold, harsh light of real-world logic. At the time, Pratchett seems to have seen the book he called The Colour of Magic as little more than a palate cleanser between more substantial ones. The cliffhanger ending was just another concession to the genre he was lampooning; maybe he’d actually write a sequel someday, maybe he wouldn’t.

The Colour of Magic was published in November of 1983, in a British print run of just 506 copies, a testament to its publisher’s low expectations. Nothing happened right away to prove they were mistaken; the books languished on shelves for months. But then Pratchett had the stroke of luck which every budding superstar author needs. Some years ago now, the BBC had broadcast a radio serial by one Douglas Adams, a comedic send-up of science fiction that was similar in spirit to what Pratchett was now doing for (or to) the fantasy genre. Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy had gone on to become a very hot property indeed, spawning three internationally bestselling novels to date along with record albums, a BBC television series, and, soon, a hit computer game. In light of all this, the BBC decided to give The Colour of Magic a try over the airwaves. Between June 27 and July 10, 1984, BBC Radio 4 broadcast an abridged reading of the book by Nigel Hawthorne, one of the stars of the hugely popular television sitcom Yes, Minister. The programs received a very good response, putting Terry Pratchett’s name on the lips of everyday Britons for the first time ever. Just like that, things started to happen. In January of 1985, Corgi, a British division of Bantam Books, published The Colour of Magic in paperback, with an initial print run of no less than 26,000 copies. A second print run was needed well before the end of the year. Discworld was off and running.

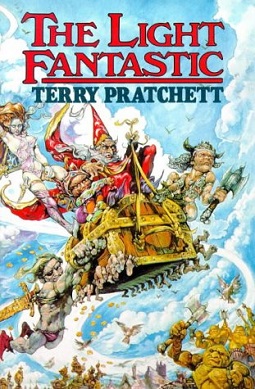

With his fiction receiving widespread attention for the first time ever, Pratchett needed little encouragement to write that sequel to The Colour of Magic now rather than later. The Light Fantastic, which was published in June of 1986, was largely more of the same, notable mostly for having a slightly more focused plot and for giving prominent place to the character of Death — you know, the skeleton dressed all in black, with the scythe and so on. Belying his terrifying appearance, Death’s Discworld persona is that of an overworked, sometimes irascible, but basically well-meaning bureaucratic functionary. In time, he became arguably the most beloved of all Pratchett’s recurring characters. Many Discworld fans, facing the last days of a loved one or even their own final exit, have found surprising comfort in the seven-foot-tall, cat-loving apparition who brings peace with him rather than pain or judgment. He was an early sign that there might be something more to Discworld than just a succession of clever gags.

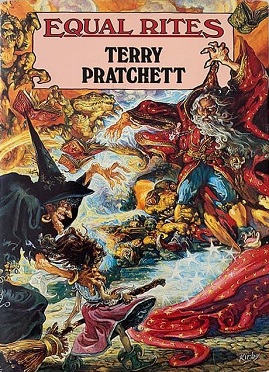

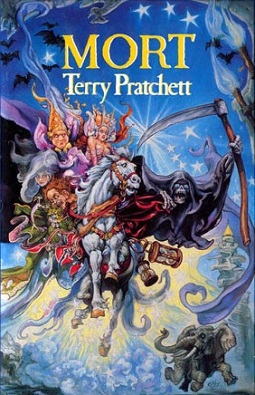

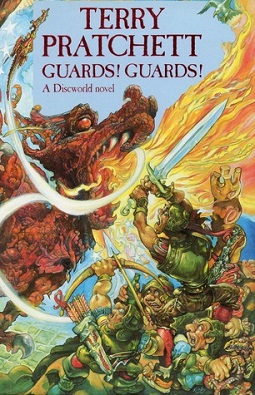

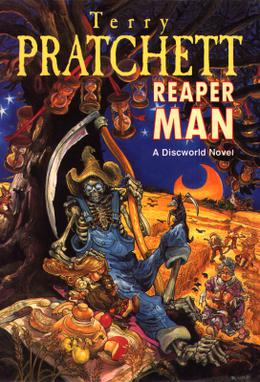

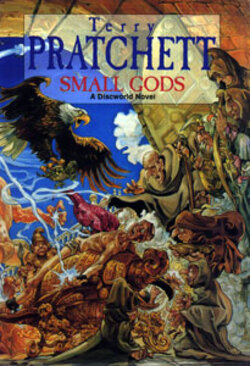

Pratchett was very fortunate to connect with an artist named Josh Kirby, whose colorful, winsome, but often subtly subversive covers became the indelible look of Discworld, impossible to separate in the minds of most fans from the words on the page.

Still, it wasn’t entirely unreasonable even at this stage to see Pratchett as an author trying his derivative darnedest to be fantasy fiction’s answer to Douglas Adams. It hadn’t helped his cause when, in a couple of unguarded early interviews, he had admitted that he had been reading the Hitchhiker’s books at the same time he was writing The Colour of Magic. Now, though, he was bristling at the comparison more and more. Adams’s works, he claimed with some truth, were archer, colder, and crueler than his own humor; Adams laughed at his characters, while Pratchett laughed with them at the absurdity of the universe.

Whether it was written in response to the accusations of unoriginality or was just a natural progression, the next book in the Discworld series made the argument that Pratchett was nothing more than a second-rate Douglas Adams untenable. That said, the leap Pratchett made with Equal Rites, the third Discworld novel, was in some ways a fairly obvious one. He was already mining humor from portraying a world of heroic fantasy in a “realistic” way, imagining the experience of the characters there who weren’t larger-than-life heroes on epic quests, and showing how even the fantastic becomes by definition mundane as soon as it becomes the stuff of everyday life. (If you doubt this truism, just look at the technological wonders all around us today which would have seemed almost like magic 30 years ago, but to which we hardly give a thought…) From here, it was a relatively short leap to begin using Discworld as a philosophical laboratory to address the questions and problems with which our own mundane societies are grappling. And yet, short leap though it may have been, it was an audacious one nonetheless. “I want to get away from the idea that I’m automatically sending fantasy up,” Pratchett would say a few years later. “What I’m concerned about now is sending up ideas, ways of looking at the world, people’s expectations.”

The phallic wand the female protagonist of Equal Rites is carrying as she claims powers usually reserved for men is a fine example of Josh Kirby’s subversive edge. Pratchett absolutely loved the image. As his characters loved to sing, “A wizard’s staff has a knob on the end…”

Published barely six months after The Light Fantastic, Equal Rites was the first Discworld novel that could be reasonably said to have overarching themes and a moral compass. Abandoning Rincewind and Twoflower for the time being, it’s a bildungsroman about the coming of age of a young girl — dangerous territory for a middle-aged male author to venture into, but Pratchett pulls it off pretty well. Of course, this being still a fantasy novel, her coming of age involves her coming into her own as a magic user, which in turn involves being apprenticed to the local witch and having many ensuing adventures. Nevertheless, the message the book hammers home relentlessly is as relevant to our own world as any message can possibly be. It’s right there in the book’s title (overlooking another dreadful pun): that women are every bit as capable as men, and deserve to be treated that way. There’s also an even broader and equally important theme, about the value of empathy in general. To illustrate this, Pratchett invents the magical skill of “borrowing,” which lets a being quite literally walk a mile in another being’s shoes — or, rather, in another being’s mind — experiencing the world as they do. If only all of us could and would do the same before we pass judgment…

The next Discworld book, Mort, was published in November of 1987, and remains among the most beloved of the canon, often recommended as an ideal place for beginners to start thanks to its very straightforward, self-contained plot. It involves Mortimer, a hapless young fellow who has just been hired for the dubious position of apprentice to Death. Among other things, the book is a sort of companion piece to Equal Rites, this story being about the travails of male adolescence. Even more so than its predecessor, Mort is elevated by its author’s essential humanity; there is no cruelty in Terry Pratchett. Pratchett:

In Mort, I keep referring to the “sex scenes,” and somebody who was interviewing me said, “But there aren’t any sex scenes in Mort!” I said, “No, but that’s what’s funny!” You see two young people who are terribly embarrassed in each other’s presence, which was about 90 percent of sex when I was a kid. That’s what it was all about: being horribly tongue-tied and embarrassed the whole time.

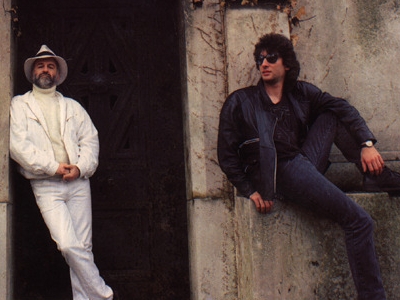

Much to Pratchett’s gratification, these most recent two, more ambitious Discworld novels sold even better than the first two, allowing him to quit his job in the civil service with the confidence of an established, bankable author. It was at this point that he separated himself from Douglas Adams in another way. If the latter had lived on the Discworld, he would doubtless have been written up as one of the practical jokes the gods there love to play on mortals: he was a brilliant writer who would rather do almost anything else than write, who, as he once memorably put it, preferred to spend his days soaking in a cozy bath and listening to deadlines whooshing by outside the window. Pratchett, on the other hand, had the work ethic of an ant colony. In the first five years after quitting his day job, he published ten Discworld novels, three non-Discworld novels for children, and the standalone novel Good Omens, a much-heralded collaboration with Neil Gaiman, author of the Sandman comic books. And then, as if all that wasn’t enough, Pratchett also found time to write a few short stories and a non-fiction book about cats.

The middle-aged family man Terry Pratchett and the too-cool-for-school hipster Neil Gaiman, hobnobber with rock stars, made an odd couple to be sure, but the two genuinely liked and respected one another, and many fans consider Good Omens to be among the best things either ever wrote.

Needless to say, we can’t hope to analyze this fire hose of output in any depth here. Suffice to say that Pratchett kept pushing at the boundaries of what a Discworld novel could be, producing everything from intricately plotted detective yarns to poignant character studies, along with the occasional unabashed satirical romp for diehard fans of Rincewind and Twoflower and their ilk. We shouldn’t get too precious about Pratchett’s books from this or any other period; as he would be the first to admit, he was first and foremost a commercial author writing with at least one eye on the needs of the market. He wasn’t above gloating a bit over each huge check that rolled in from his publisher, and very much wanted to keep the money spigot open. Doubtless many of his books could have been even better if he had spent more time with them, if he hadn’t felt compelled to rush pell-mell to the next one. On the other hand, much the same thing can be said of many another highly regarded author, and not just in the genre literatures; the names of William Shakespeare and Charles Dickens come to mind as just two of history’s insanely prolific writers-for-hire with a surfeit of genius.

We might pull out just a few books from this era by way of illustrating just how far Discworld could stray from the template of The Colour of Magic. Take, for example, the 1989 novel Guards! Guards!, another one often recommended by the Discworld cognoscenti as an excellent starting point.

In it, a cabal summons a dragon to lay piecemeal waste to the sprawling metropolis of Ankh-Morpork, the biggest city on the Disc. One of the usually shiftless Ankh-Morpork police force, a fellow named Sam Vimes who would go on to become the most frequently recurring Discworld-novel protagonist of all, has the bright idea of actually investigating for a change, leading to both comedy and drama. Guards! Guards! can be considered a landmark in the evolution of the Discworld series thanks to the presence of Vimes alone. He is, claims Pratchett’s biographer Burrows, “a character that grew out of Pratchett’s need to put his personality on the page. Vimes is a deposit for the author’s burning anger, and is fueled by a deep sense of injustice that Pratchet had so far managed to keep a lid on. The character is utterly flawed. He’s a drunk, he spends his life miserable, and, despite a keen intelligence, has a habit of speaking truth to power that has kept him from rising further than the city’s least-desirable command — captain of the night watch.”

Writing in a genre famous for seeing good and evil as (sometimes all too literally) white and black, Pratchett understands how the gray of ordinary people leading ordinary lives can slowly but surely turn into deepest ebony.

There are people who will follow any dragon, worship any god, ignore any inequity. All out of a kind of humdrum, everyday badness. Not the really high, creative loathsomeness of the great sinners, but a sort of mass-produced darkness of the soul. Sin, you might say, without a touch of originality. They accept evil not because they say yes, but because they don’t say no.

Or take 1991’s Reaper Man, the second Discworld novel with Death as a main protagonist. The books begins with a crazy premise: that Death has retired to become a farmhand, which causes serious problems on the Disc as everyone currently alive becomes suddenly immortal. What initially seems like nothing but another clever gag becomes in due course a wise, compassionate meditation on time and its passing, on how birth and death are the natural, necessary way of the universe, on how old lives must ultimately end to make space for young ones.

No one is finally dead until the ripples they cause in the world die away — until the clock he made winds down, until the wine she made has finished its ferment, until the crop they planted is harvested. The span of someone’s life is only the core of their actual existence.

Or take 1992’s Small Gods, a simultaneously satirical and sympathetic examination of the eternal human quest for Higher Truths, told from the standpoint of both idealists and cynics.

Take it from me, whenever you see a bunch of buggers puttering around talking about truth and beauty and the best way of attacking Ethics, you can bet your sandals it’s because dozens of other poor buggers are doing all the real work around the place…

Here’s a riff on Plato that comes about as close as any passage can to summing up Pratchett’s philosophy of a happy life:

Life in this world is, as it were, a sojourn in a cave. What can we know of reality? For all we see of the true nature of existence is, shall we say, no more than bewildering and amusing shadows cast upon the inner wall of the cave by the unseen blinding light of absolute truth, from which we may or may not deduce some glimmer of veracity, and we as troglodyte seekers of wisdom can only lift our voices to the unseen and say, humbly, “Go on, do Deformed Rabbit… it’s my favorite.”

And then there’s my very favorite, as cogent an argument for the value of blue-sky research as I’ve ever read:

It’s always worth having a few philosophers around the place. One minute it’s all Is Truth Beauty and Is Beauty Truth, and Does A Falling Tree in the Forest Make A Sound if There’s No One There to Hear It, and then, just when you think they’re going to start dribbling, one of ’em says, “Incidentally, putting a thirty-foot parabolic reflector on a high place to shoot the rays of the sun at an enemy’s ships would be a very interesting demonstration of optical principles.”

By the early 1990s, Pratchett had managed an incredible, not to say paradoxical, feat: he had busted right out of the fantasy ghetto whilst remaining an unapologetic genre author in outlook and orientation. You were guaranteed to see at least one or two Discworld novels during any given trip on the London Underground, as often as not clutched in the hands of riders who were not your stereotypical fantasy nerds. Discworld cut across all the usual boundaries of class, age, race, and gender. In 1992, W.H. Smith, the biggest bookstore chain in Britain, stated that 10 percent of their total science-fiction and fantasy sales consisted of Terry Pratchett books. By 1998, Pratchett accounted for 2 percent of all their revenues. When you combined the sales of all of his novels together, he became simply the most popular single British author of the 1990s. There was something comforting in the way that these unpretentiously entertaining, gently wise books were able to hold their own and then some against all of the latest controversial political screeds and tawdry celebrity memoirs. If Discworld wasn’t quite great literature, it was certainly a cut above most of the rest of the bestseller list.

Pratchett himself was only slightly slowed by the interviews and book signings that came with being Britain’s most popular living author; he continued to crank out a reliable two books per year. Unlike so many authors whose names have become a brand, Pratchett never stooped to hiring ghostwriters to create his content; every word in every Discworld novel was his own. He became a very rich man, but that didn’t slow him down either. Clearly money wasn’t the main reason he wrote. While he enjoyed it in a way, that way was mostly as a handy measure of his success; his actual lifestyle changed surprisingly little.

For all of Discworld‘s 1990s popularity in Britain and some other parts of Europe — Germany proved another especially strong market — it never became more than a cult phenomenon in the United States. (Tellingly, the British edition of Good Omens listed Pratchett’s name first as the more salable author, while the American edition did just the opposite.) This relative failure irked Pratchett, who went so far as to rewrite parts some of his books to better suit what he judged to be the American comedic sensibility. Nonetheless, he wouldn’t manage to place a book on the New York Times bestseller list until 2004.

There really are no obvious American analogues for Pratchett’s place in British pop culture during the decade before that one. Piers Anthony churned out whimsical fantasy novels set in his own pun-strewn world of Xanth at almost as prodigious a pace, and fostered a similarly personal connection with his readers, but his series was vastly more crass, formulaic, and juvenile, not at all the sort of thing most respectable adults were willing to be caught reading on a train.

Confined to Europe though it was, the 1990s Discworld mania was very real and very huge. In addition to the novels themselves, there were television cartoons, audio books, music CDs, collectible figures and toys, tee-shirts and other clothing, jewelry, candles, maps, companion source books, quiz books, a tabletop role-playing game, paper fanzines, conventions, websites, and one of the most popular newsgroups on Usenet: alt.fan.Pratchett, where the author himself occasionally dropped by to leave a post. “Anyone could be a Discworld fan,” writes Marc Burrows, “and sometimes it felt like just about everybody was.”

Naturally, then, there were also computer games…

(Sources: the books The Magic of Terry Pratchett by Marc Burrows and The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction edited by Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn; Starlog of August 1990 and May 2000. And of course the many books of Terry Pratchett!)

CJ

July 22, 2022 at 3:53 pm

Thrilled that we’re getting a multi-part series on one of my favorite authors! Pratchett was quite a revelation to Younger Me, and I still revisit Discworld frequently.

One thing I love about the books is how the jokes often defy concise quoting. I frequently use “…and Björn Stronginthearm’s your uncle” in chats, in reference to an early bit in Guards! Guards! (a pair of dwarves discussing what to do with young Carrot). The joke’s nearly impossible to cut out of the book, though — it spans at least half a page and more than one paragraph. He was really good at weaving that kind of thing throughout long passages, and even across many chapters.

Relatedly, that’s one of the reasons the non-book versions of Discworld stories generally don’t work very well for me; there’s just not *time* to give the jokes the room they need, if you’re constrained to a few hours of screen time and need to keep the plot moving.

Jack Brounstein

July 22, 2022 at 4:36 pm

I have an incredible soft spot for Terry Pratchett, and end up re-reading much of his catalogue every few years when I want a break from more serious fare. I have to admit I was a little worried going in to this article—for as much as I enjoy the work, there is a formula there, and I wasn’t sure I was emotionally ready for one of my favorite bloggers to tear down one of my favorite authors.

I’m looking forward to reading about the Discworld adventure games, which I’ve never played and heard somewhat negative things about. I’ve always been most curious about Discworld Noir, though it looks like that wasn’t released until 1999; I like hard-boiled pastiche a good deal more than I like general fantasy (or most actual hard-boiled detective stories), which is probably why I’ve also always gravitated to the Night Watch books. Speaking of…

> a fellow named Sam Vimes who would go on to become the most frequently recurring Discworld character of all

This is true for starring roles or number of pages, but I think in terms of books featuring the character it has to be Death.

Jimmy Maher

July 23, 2022 at 7:30 am

Fair enough. Thanks!

Cdrjameson

July 24, 2022 at 4:29 pm

Don’t forget the Librarian, who pops up pretty much every time.

Peter Olausson

July 22, 2022 at 6:12 pm

There are plenty of Pratchett quote collections. Wikiquote has a lengthy one I keep returning to, as a virtually endless source of Pratchettiana. If anyone still wonders why one ought to read him, this might be a good place to start.

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Discworld

Ignacio

July 22, 2022 at 6:24 pm

Great piece! Thanks!!

One little typo: “it never becOme more”.

Jimmy Maher

July 23, 2022 at 7:32 am

Thanks!

Nathan Myers

July 22, 2022 at 7:38 pm

The live-action dramatic productions of his work have turned out very well, most particularly Hogfather, with a young Michelle Dockery in the lead as DEATH’s granddaughter. Casting throughout is inspired.

Andy North

July 22, 2022 at 7:53 pm

Fun fact: the character of Twoflower wears glasses, which Rincewind has never seen before and mistakenly interprets as a second pair of eyes, in a throwaway joke about “four eyes” being a popular insult for nerds. Josh Kirby misunderstood and painted the character with four physical eyes on the cover of The Light Fantastic that you link in the article.

I think Terry addressed this at some point but can’t find the quote – basically that he thought the mistake was funny enough that he didn’t insist on it being corrected.

Jimmy Maher

July 23, 2022 at 7:36 am

Yes, there’s some additional discussion of this in Burrows’s biography. Pratchett took a writerly lesson from the whole mix-up — that he shouldn’t outsmart himself by trying to be too clever, that he should remember that clarity also has a value. A very good lesson for all writers, one we all need to relearn from time to time.

Armcie

July 22, 2022 at 8:41 pm

Colin Smythe initially commissioned Terry to write some short stories/novellas, which then became The Colour of Magic, which goes some way to explain its disjointed nature.

Jeff Thomas

July 22, 2022 at 8:47 pm

This is a welcome and pleasant surprise. I distinctly remember the day in a used bookstore (“a good bookshop is just a genteel Black Hole that knows how to read” — Pratchett) that I spotted a dog-eared copy of Guards Guards and thought to myself, “Hey, that’s the guy who wrote Good Omens with Neil Gaiman, I wonder what he’s been up to?” What indeed. That moment was as moments in my reading life as the time I snuck The Fellowship of the Ring from my parents bedroom at 12 (I was too young, according to them) or when a school mate lent me his Foundation trilogy in Junior High. Pratchett had the amazing ability to wrap social commentary and big ideas into clever and amusing stories full of great humor AND humanity. He has the BEST take on elves too.

Yes, many people see him putting himself into his world as Vimes, and there’s probably something to that. But I personally think he put more of himself into Granny Weatherwax who was cornered into being The Good One because the role of Villain was already taken, and she wasn’t too happy about it. He saw all the injustice of the world, and the flaws in human nature that allowed them to happen, and it really angered him. If he could have taken a more active role than writing scathing social commentary disguised as popular entertainment he certainly would have.

“The trouble is, you see, that if you do know Right from Wrong, you can’t choose Wrong. You just can’t do it and live. So.. if I was a bad witch I could make Mister Salzella’s muscles turn against his bones and break them where he stood… if I was bad. I could do things inside his head, change the shape he thinks he is, and he’d be down on what had been his knees and begging to be turned into a frog… if I was bad. I could leave him with a mind like a scrambled egg, listening to colors and hearing smells…if I was bad. Oh yes.” There was another sigh, deeper and more heartfelt. “But I can’t do none of that stuff. That wouldn’t be Right.”

She gave a deprecating little chuckle. And if Nanny Ogg had been listening, she would have resolved as follows: that no maddened cackle from Black Aliss of infamous memory, no evil little giggle from some crazed Vampyre whose morals were worse than his spelling, no side-splitting guffaw from the most inventive torturer, was quite so unnerving as a happy little chuckle from a Granny Weatherwax about to do what’s Right.” — Terry Pratchett

He wrote over 50 books in his career, and yet he still died far, far too soon. I’m really looking forward to you covering his computer adventures, although I such a huge fan and have loved adventure games since I first played Colossal Cave on a PDP/11 I haven’t had a chance to get a working copy of any of them. His non-book works are still hard to get in America, though I can heartily recommend Neil Gaiman’s tv production of Good Omens which Gaiman has said he did as a homage to is old friend, constantly asking himself “what would Terry do?” while making it. It’ll be interesting to see what he does with a second season.

#GNUTerryPratchett

Andrew Plotkin

July 23, 2022 at 1:16 am

> But I personally think he put more of himself into Granny Weatherwax…

Or, arguably, Lord Vetinari. Always behind the scenes. Responsible for every soul in Ankh-Morpork. Spends his life working on a life-spanning scheme to ensure that the city can survive past his death.

(Also, often acts by winding Sam Vimes up.)

GNUTerryPratchett indeed.

deiseach

July 23, 2022 at 7:19 pm

“Responsible for every soul in Ankh-Morpork”

And twice as many people.

Jeff Thomas

July 23, 2022 at 8:06 pm

Indeed. There is probably some truth to all of this. He put his heart and soul into these books, each character a different reflection of him. This is why they are so human.

Peter Olausson

July 22, 2022 at 11:47 pm

By the way, there’s at least one direct computer reference in the Discworld geography: The Ramtop mountains. On the ZX Spectrum, the system variable RAMTOP is the highest memory address used by BASIC. Everything above is thus protected from NEW, and eg a suitable place to put machine code.

Jimmy Maher

July 23, 2022 at 7:37 am

A Spectrum was Pratchett’s second computer, which he sold in favor of an Amstrad. ;)

Michael Brazier

July 23, 2022 at 2:30 am

The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic aren’t really sending up Tolkien and his imitators; they’re sending up the older “sword and sorcery” type of fantasy, Robert E. Howard and Fritz Lieber and their ilk. Indeed, both books are quite similar to a Fafrhd and Grey Mouser collection of stories – not just because Lieber’s heroes were a duo while Howard’s worked alone, but also because Lieber was not … invariably serious. (I don’t remember a single time when Howard put a joke in his stories.)

Tolkien riffs do turn up occasionally in the Discworld – Captain Carrot bears a strong resemblance to Aragorn, for instance, and there’s the dwarfs – but the structure of Tolkienesque “epic fantasy” doesn’t really get into any of the books. Even the ones that bring in literally cosmos-shaking threats don’t echo the plot of The Lord of the Rings.

WellTemperedClavier

July 23, 2022 at 5:36 am

I’ve never been able to really get into Pratchett’s work. After a few aborted attempts in grade school, I more recently tried “Guards! Guards!” at a friend’s recommendation, and just could not get engaged. The humor never managed to get more than a weak chuckle from me. Pratchett’s observations somehow felt unwelcome even though I largely agreed with them. Maybe they felt too much like an authorial intrusion on the narrative.

I’m baffled as to why it didn’t click. Based on what you write about Pratchett, his work sounds exactly like the kind of thing I’d be most interested in. One of the ways in which I judge a fictional setting is whether or not I can imagine living there as a regular person (and if it passes, I’ll probably like the setting). Likewise, I’ve often said I want to see more about the mundane sides of fantasy worlds. Everyone I know speaks highly of Pratchett, to the point that me not liking his books is starting to feel like a moral failing on my part.

Regardless, your post helps me see the value in Pratchett’s work. Fantasy (and a fair amount of “realist” literature as well) relies so heavily on the big picture that it easily loses touch with the human. We don’t all fit into neat categories and great social problems can’t be solved by killing one evil wizard. Any author who emphasizes such truths is doing a good thing, in my opinion, regardless of my personal enjoyment.

Mike Taylor

July 25, 2022 at 1:25 pm

“Everyone I know speaks highly of Pratchett, to the point that me not liking his books is starting to feel like a moral failing on my part.,

That is exactly how i feel about Bob Dylan.

Jimmy Maher

July 25, 2022 at 1:59 pm

He can be hit or miss for me as well, but when he nailed it back in the day, he nailed it good. I have this theory that every songwriter is born with a limited supply of interesting and original melodies. If so, Dylan’s well of same ran dry about 40 years ago. To compensate, he’s leaned heavily recently into the whole Nobel Prize-winning poet thing, speak-singing over repetitive blues chords. Lord save us from songwriters who’ve decided they’re really poets!

Anyway, even Dylan’s classic songs can be an easier sell when not sung by Dylan. Emma Swift released a lovely Dylan covers album not too long ago: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2R94s8vxi9A. (Although even in this context, twelve minutes of “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” is about eight minutes too many…)

Oneeep

July 21, 2024 at 4:32 pm

What a dreadful lapse of taste on your part.

Gnoman

July 23, 2022 at 7:16 am

The inability to rise above “cult” status in the US is one of the biggest similarities between Pratchett and Adams. I’ve never quite understood why, despite being one of the Americans for whom neither ever really clicked. There’s no fundamental cultural missteps that I’ve seen, they just have no “grip”, so to speak.

Jimmy Maher

July 23, 2022 at 7:49 am

Douglas Adams did much better in the United States than Terry Pratchett. His books were bestsellers there during the 1980s, and were certainly very well known to me and my nerdy friends. Witness the success of Infocom’s Hitchhiker game. The Discworld text adventure, by contrast, never even found an American publisher. There just wasn’t enough of a market for it.

I think Adams was an easier sell to American teenagers because there’s a more direct through-line from the likes of Monty Python, which we never tired of watching and parroting ad nauseum, to Hitchhiker’s. Adams was doing social commentary of a sort — I’ve argued elsewhere that the line from P.G. Wodehouse to Hitchiker’s is more pronounced than any science-fiction influence — but, with occasional exceptions (So Long Thanks For All the Fish springs to mind) he didn’t show much interest in coherent world-building or the inner lives of his characters. Pratchett’s work was more subtle and more ambitious. For this reason, it didn’t quite fit into that comfortable “British comedy” box. Americans weren’t sure what to make of it.

Gnoman

July 23, 2022 at 11:23 am

Adams being a Space Guy probably helped – there were far more space-themed works with mainstream success (Star Trek, Battlestar Galactica, Star Wars, etc) when he made his debut than there were fantasy ones.

That said “nerdy” is kind of the key word there. Both Monty Python and Douglas Adams are things that I only really encountered from the “ghettoed” population – the folks already into sci-fi and fantasy and comics. The exception being ex-military people who spent a great deal of time stationed oversea. The same is true of Pratchett, despite his fans being far less inclined to annoying repetitive quotes.

Meanwhile just about every third British person I’ve encountered is a fan, even if they don’t fit into that demographic. I’ve never been able to figure out quite what causes the difference, any more than I can figure out why my own reaction is so negative despite everything in the books being normally right up my alley.

Chris D

July 23, 2022 at 12:28 pm

I think the Monty Python link being part of Adam’s appeal to American readers is very true. One other thing I would suggest is that while both Adams and Pratchett are very English writers, Pratchett’s style reflects an England you don’t often see in films and novels. Adams is much more upper-middle class than Pratchett, having been to public school & Cambridge, and having worked for the BBC. Pratchett’s humour and characters have more of a lower-middle / working class background, and those characters and situations may be less familiar to US audiences just because they turn up in films less often (or at least, films that are popular outside of the UK).

I’m thinking of bits like the scene in Guards! Guards! where the watchmen get distracted by the suggestion of eating beef dripping on bread and rhapsodise about it for ages, or particularly, Granny Weatherwax and her family, who are portrayed in a way that would be very familiar to UK readers – within a page or two, they’re clearly the kind of family you might find on any council estate in the UK, but portrayed with a real warmth and insight, in a non-condescending way that is quite unlike the way most UK media portrays poor families. I suspect most people in the UK would respond to that character immediately, but they might not set off that feeling of recognition in other countries.

Andrew Plotkin

July 23, 2022 at 4:35 pm

> Granny Weatherwax and her family

I trust you mean Nanny Ogg :)

It’s worth pointing out that American *fantasy readers* were keenly aware of Pratchett and, in general, were big fans. Some people never got into them (pace the commenters above) but many more loved the books and hovered around the bookstore waiting for each new one. US fantasy *writers* loved Pratchett; bookstore owners loved Pratchett. The 90s were the era of Big Awesome Bookstores (Borders, B&N) and there were rows of Pratchett hardbacks lined up on the shelves.

What Pratchett never got was the mainstream US pop-culture breakout that Douglas Adams and (later) Rowling got.

Chris D

July 23, 2022 at 5:08 pm

Yes! It’s been a while since I read any Pratchett, and I did wonder whether I was thinking of Nanny Ogg.

Drew

July 23, 2022 at 3:37 pm

This is awesome. Can’t wait for more.

Alex

July 23, 2022 at 6:43 pm

This article perfectly describes why Pratchett is something special to me when it comes to Fantasy. Of course I knew his name and the name of Discworld for many years, but I´ve never read any of his books until two years ago. I just wasn´t interested enough to buy them and I never saw copies at flea markets or garage sales (I don´t know if he is that popular in Austria). Anyway, I have an aunt who lives in Britain part-time and who is an avid reader. She has got many of his books and lend me one which I read during the pandemic. I was really surprised about basically everything you wrote here. In general, I´m not really a fan of comedic fantasy, but this is really something different. I found one of the books in a german translation in a public book case a few weeks ago, but I have to read it yet. Good job, as always!

Steve Nicholson

July 24, 2022 at 8:53 pm

Count me as another American who knew nothing about Terry Pratchett. I did read Good Omens years ago and remember liking it. But after seeing the Good Omens TV series (which I consider among the finest things ever broadcast) I thought I should look into his other writings. When I saw how many books there were in the Discworld series and calculated how many hundreds of dollars it would cost to get them all (I’m, unfortunately, an uncontrollable completist) I balked.

Reading this makes me think about reconsidering. Maybe I should start hitting up used book stores.

Tom Cleaveland

July 27, 2022 at 7:16 pm

Steve: check your local library if you haven’t already. I’m fortunate that mine has the complete series and maybe yours does as well.

cpt kangarooski

July 25, 2022 at 6:20 am

Regarding the caption for Equal Rites, I’m fairly sure that what Esk is holding there is her staff (disguised as a broom); it’s just that she’s holding it on her left, and we see her from her right.

Leo Vellès

July 26, 2022 at 1:47 pm

I never read any one of his books, but for those who haven´t played the first Discworld computer game and aren`t sure if it is worthy to play it because all the ill reputation about it`s puzzles: play it with a walkthrough by your side and don´t be ashamed! Yes, the puzzles are nonsensical and surely a candidate for the most moon logic puzzle design of all time….but, but……the graphics are gorgeous, the humor is top notch, and the voice work is simply supeb. The cast is flawless, and Eric Idle as Rincewind is the funniest thing I ever heard (Idle can read all day a medical prescription an still be funny as hell).

Discworld 2 is more classic about it`s puzzle design and can be finished without any walkthrough. It`s a very good game, but I don`t know why I liked more the first one, with all the flaws that the sequel don´t have.

Pog

July 27, 2022 at 1:13 am

It’s the first time of my life I am reading “pell mell”. Well, it’s pêle-mêle, and you should write it en français dans le texte, because that looks very odd to my French eyes. Continue the great work ! (I am the guy giving 30 euros per article for a few years now through Patreon, and I would like more articles per year ahah !)

Gnoman

July 27, 2022 at 1:36 am

Why would the English phrase “pell mell” be spelled as if it were French? It isn’t French, it is English.

Jimmy Maher

July 27, 2022 at 7:56 am

For 30 euros per article I’m tempted to give you what you want, but editorial ethics must be upheld. ;) Thanks for your support!

Pog

July 27, 2022 at 9:23 pm

It’s the first time I read “pell mell”, I thought it was the French expression “pêle mêle” weirdly translated… which it is, in a way, because I found that “pêle mêle” was the inspiration of “pell mell”. But it looks like part of English now, so ok. I hope I will never hear it though, it might sound horrendous.

Jimmy Maher

July 28, 2022 at 5:05 am

I daresay most of English sounds horrendous compared to French. ;)

Tom Cleaveland

July 27, 2022 at 7:14 pm

I binge-read the Discworld series through Reaper Man and just haven’t had the energy to keep going. Much of that book and Moving Pictures seemed to me to be “cranky old man” satire and I had to force myself to finish. Death’s relationship with Miss Flitworth was written with such tenderness and it deserved a better side story.

My favorite among the first 11 books is Wyrd Sisters, a satire–and a warning–concerning language, memory, and history.

All in all a brilliant set of books so far, very much of a lineage of satire that includes Gulliver’s Travels.

Wolfeye Mox

July 27, 2022 at 8:13 pm

I’ve read all but one of the Discworld books. I still haven’t read the last one, because I always want Terry to have another story to tell me.

Brian Bagnall

July 31, 2022 at 2:54 pm

I started reading The Colour of Magic in light of this article, and with the fourth and final part of the book remaining, my impression is that he is a brilliant writer in many ways. I marvel at the imagination in his prose, and slightly less at the scenarios he invents. Definitely a lot is owed to Monty Python and Douglas Adams. The first half of the book is the strongest while the later parts seem more unmoored and without any particular goal or drive for the characters. They just sort of wander around from one random thing to the next, which doesn’t exactly keep me glued to the page. As this article mentions the later books are more focused so I will probably give them a try.

James

August 13, 2022 at 2:06 am

“Adams’s works, he claimed with some truth, were archer, colder, and crueler than his own humor;”

Does Archer have a special meaning in this context? I’ve never come across it before.

Jimmy Maher

August 13, 2022 at 7:08 am

As an adjective, “arch” means humorous in a sly, crafty way that has more to do with the head than the heart.