To the person who [is] contemplating buying this game, what would I say? I would say take your money and give it to the homeless, you’ll do more good. But if you are mad to buy this game, you’ll probably have a hell of a lot of fun playing it, it will probably make you uneasy, and you’ll probably be a smarter person when you’re done playing the game. Not because I’m smarter, but because everything was done to confuse and upset you. I am told by people that it is a game unlike any other game around at the moment and I guess that’s a good thing. Innovation and novelty is a good thing. It would be my delight if this game set a trend and all of the arcade bang-bang games that turn kids into pistol-packing papas and mamas were subsumed into games like this in which ethical considerations and using your brain and unraveling puzzles become the modus operandi. I don’t think it will happen. I don’t think you like to be diverted too much. So I’m actually out here to mess with you, if you want to know it. We created this game to give you all the stuff you think you want, but to put a burr into your side at the same time. To slip a little loco weed into your Coca-Cola. See you around.

— Harlan Ellison

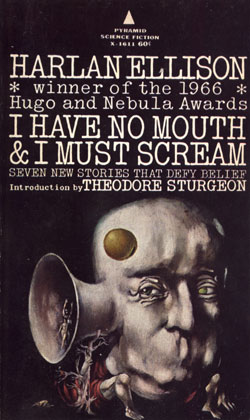

Harlan Ellison made a very successful career out of biting the hands that fed him. The pint-sized dervish burst into literary prominence in the mid-1960s, marching at the vanguard of science fiction’s New Wave. In the pages of Frederick Pohl’s magazine If, he paraded a series of scintillatingly trippy short stories that were like nothing anyone had ever seen before, owing as much to James Joyce and Jack Kerouac as they did to Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein. Ellison demanded, both implicitly in his stories and explicitly in his interviews, that science fiction cast off its fetish for shiny technology-fueled utopias and address the semi-mythical Future in a more humanistic, skeptical way. His own prognostications in that vein were almost unrelentingly grim: “‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman” dealt with a future society where everyone was enslaved to the ticking of the government’s official clock; “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” told of the last five humans left on a post-apocalyptic Earth, kept alive by an insane artificial intelligence so that he could torture them for all eternity; “A Boy and His Dog” told of a dog who was smarter than his feral, amoral human master, and helped him to find food to eat and women to rape as they roamed another post-apocalyptic landscape. To further abet his agenda of dragging science fiction kicking and screaming into the fearless realm of True Literature, Ellison became the editor of a 1967 anthology called Dangerous Visions, for which he begged a diverse group of established and up-and-coming science-fiction writers to pick a story idea that had crossed their mind but was so controversial and/or provocative that they had never dared send it to a magazine editor — and then to write it up and send it to him instead.

Ellison’s most impactful period in science fiction was relatively short-lived, ending with the publication of the somewhat underwhelming Again, Dangerous Visions in 1972. He obstinately refused to follow the expected career path of a writer in his position: that of writing a big, glossy novel to capitalize on the cachet his short stories had generated. Meanwhile even his output of new stories slowed in favor of more and more non-fiction essays, while those stories that did emerge lacked some of the old vim and vinegar. One cause of this was almost certainly his loss of Frederick Pohl as editor and bête noire. Possessing very different literary sensibilities, the two had locked horns ferociously over the most picayune details — Pohl called Ellison “as much pain and trouble as all the next ten troublesome writers combined” — but Pohl had unquestionably made Ellison’s early stories better. He was arguably the last person who was ever truly able to edit Harlan Ellison.

No matter. Harlan Ellison’s greatest creation of all was the persona of Harlan Ellison, a role he continued to play very well indeed right up until his death in 2018. “He is a test of our credulity,” wrote his fellow science-fiction writer David Gerrold in 1984. “He is too improbable to be real.”

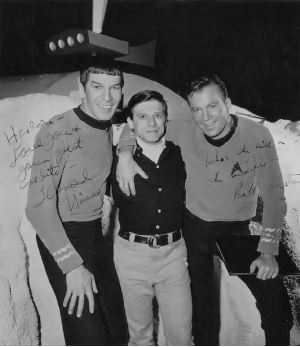

The point of origin of Harlan Ellison as science fiction’s very own enfant terrible can be traced back to the episode of Star Trek he wrote in 1966. “The City on the Edge of Forever” is often called the best single episode of the entire original series, but to Ellison it was and forever remained an abomination in its broadcast form. As you may remember, it’s a time-travel story, in which Kirk, Spock, and McCoy are cast back into the Great Depression on Earth, where Kirk falls in love with a beautiful social worker and peace activist, only to learn that he has to let her die in a traffic accident in order to prevent her pacifism from infecting the body politic to such an extent that the Nazis are able to win World War II. As good as the produced version of the episode is, Ellison insisted until his death that the undoctored script he first submitted was far, far better — and it must be acknowledged that at least some of the people who worked on Star Trek agreed with him. In a contemporaneous memo, producer Bob Justman lamented that, following several rounds of editing and rewriting, “there is hardly anything left of the beauty and mystery that was inherent in the screenplay as Harlan originally wrote it.” For his part, Ellison blamed Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry loudly and repeatedly for “taking a chainsaw” to his script. In a fit of pique, he submitted his undoctored script for a 1967 Writers Guild Award. When it won, he literally danced on the table in front of Roddenberry inside the banquet hall, waving his trophy in his face. Dorothy Fontana, the writer who had been assigned the unenviable task of changing Ellison’s script to fit with the series’s budget and its established characters, was so cowed by his antics that for 30 years she dared not tell him she had done so.

Despite this incident and many another, lower-profile one much like it, Ellison continued to work in Hollywood — as, indeed, he had been doing even before his star rose in literary science-fiction circles. Money, he forthrightly acknowledged, was his principal reason for writing for a medium he claimed to loathe. He liked creating series pilots most of all, he said, “because when they screw those up, they just don’t go on the air. I get paid and I’ve written something nice and it doesn’t have to get ruined.” His boorish behavior in meetings with the top movers and shakers of Hollywood became legendary, as did the lawsuits he fired hither and yon whenever he felt ill-used. Why did Hollywood put up with it? One answer is that Harlan Ellison was at the end of the day a talented writer who could deliver the goods when it counted, who wasn’t unaware of the tastes and desires of the very same viewing public he heaped with scorn at every opportunity. The other is that his perpetual cantankerousness made him a character, and no place loves a character more than Hollywood.

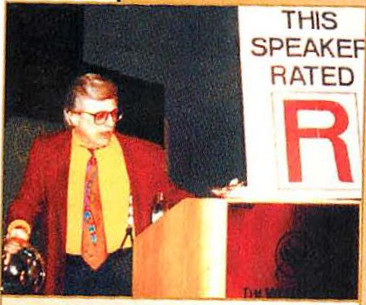

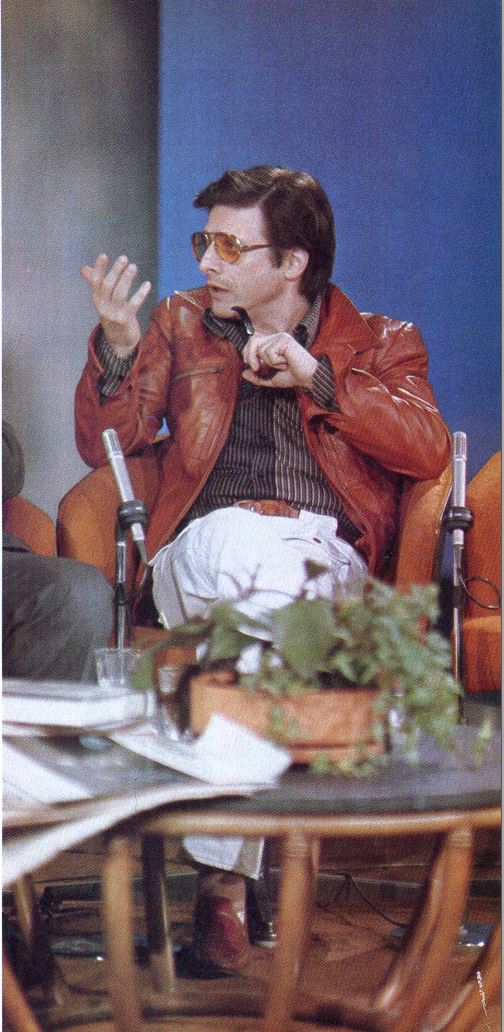

Then again, one could say the same of science-fiction fandom. Countless fans who had read few to none of Ellison’s actual stories grew up knowing him as their genre’s curmudgeonly uncle with the razor wit and the taste for blood. For them, Harlan Ellison was famous simply for being Harlan Ellison. Any lecture or interview he gave was bound to be highly entertaining. An encounter with Ellison became a rite of passage for science-fiction journalists and critics, who gingerly sidled up to him, fed him a line, and then ducked for cover while he went off at colorful and profane length.

Harlan Ellison was a talk-show regular during the 1970s. And small wonder: drop a topic in his slot, and something funny, outrageous, or profound — or all three — was guaranteed to come out.

It’s hard to say how much of Ellison’s rage against the world was genuine and how much was shtick. He frequently revealed in interviews that he was very conscious of his reputation, and hinted at times that he felt a certain pressure to maintain it. And, in keeping with many public figures with outrageous public personas, Ellison’s friends did speak of a warmer side to his private personality, of a man who, once he brought you into his fold, would go to ridiculous lengths to support, protect, and help you.

Still, the flame that burned in Ellison was probably more real than otherwise. He was at bottom a moralist, who loathed the hypocrisy and parsimony he saw all around him. Often described as a futurist, he was closer to a reactionary. Nowhere could one see this more plainly than in his relationship to technology. In 1985, when the personal-computer revolution had become almost old hat, he was still writing on a mechanical typewriter, using reasoning that sounded downright Amish.

The presence of technology does not mean you have to use that technology. Understand? The typewriter that I have — I use an Olympia and I have six of them — is the best typewriter ever made. That’s the level of technology that allows me to do my job best. Electric typewriters and word processors — which are vile in every respect — seem to me to be crutches for bad writing. I have never yet heard an argument for using a word processor that didn’t boil down to “It’s more convenient.” Convenient means lazy to me. Lazy means I can write all the shit I want and bash it out later. They can move it around, rewrite it later. What do I say? Have it right in your head before you sit down, that’s what art is all about. Art is form, art is shape, art is pace, it is measure, it is the sound of music. Don’t write slop and discordancy and think just because you have the technology to cover up your slovenliness that it makes you a better writer. It doesn’t.

Ellison’s attitude toward computers in general was no more nuanced. Asked what he thought about computer entertainment in 1987, he pronounced the phrase “an oxymoron.” Thus it came as quite a surprise to everyone five years later when it was announced that Harlan Ellison had agreed to collaborate on a computer game.

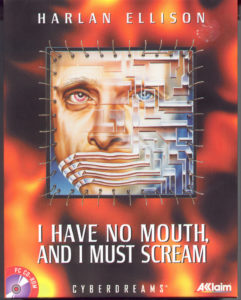

The source of the announcement was a Southern California publisher and developer called Cyberdreams, which had been founded by Pat Ketchum and Rolf Klug in 1990. Ketchum was a grizzled veteran of the home-computer wars, having entered the market with the founding of his first software publisher DataSoft on June 12, 1980. After a couple of years of spinning their wheels, DataSoft found traction when they released a product called Text Wizard, for a time the most popular word processor for Atari’s 8-bit home-computer line. (Its teenage programmer had started on the path to making it when he began experimenting with ways to subtly expand margins and increase line spacings in order to make his two-page school papers look like three…)

Once established, DataSoft moved heavily into games. Ketchum decided early on that working with pre-existing properties was the best way to ensure success. Thus DataSoft’s heyday, which lasted from roughly 1983 to 1987, was marked by a bewildering array of television shows (The Dallas Quest), martial-arts personalities (Bruce Lee), Sunday-comics characters (Heathcliff: Fun with Spelling), blockbuster movies (Conan, The Goonies), pulp fiction (Zorro), and even board games (221 B Baker St.), as well as a bevy of arcade ports and British imports. The quality level of this smorgasbord was hit or miss at best, but Ketchum’s commercial instinct for the derivative proved well-founded for almost a half a decade. Only later in the 1980s, when more advanced computers began to replace the simple 8-bit machines that had been the perfect hosts for DataSoft’s cheap and cheerful games, did his somewhat lackadaisical attitude toward the nuts and bolts of his products catch up to him. He then left DataSoft to work for a time at Sullivan Bluth Interactive Media, which made ports of the old laser-disc arcade game Dragon’s Lair for various personal-computing platforms. Then, at the dawn of the new decade, he founded another company of his own with his new partner Rolf Klug.

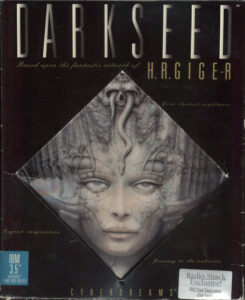

The new company’s product strategy was conceived as an intriguing twist on that of the last one he had founded. Like DataSoft, Cyberdreams would rely heavily on licensed properties and personalities. But instead of embracing DataSoft’s random grab bag of junk-food culture, Cyberdreams would go decidedly upmarket, a move that was very much in keeping with the most rarefied cultural expectations for the new era of multimedia computing. Their first released product, which arrived in 1992, was called Dark Seed; it was an adventure game built around the striking and creepy techno-organic imagery of the Swiss artist H.R. Giger, best known for designing the eponymous creatures in the 1979 Ridley Scott film Alien. If calling Dark Seed a “collaboration” with Giger is perhaps stretching the point — although Giger licensed his existing paintings to Cyberdreams, he contributed no new art to the game — the end result certainly does capture his fetishistic aesthetic very, very well. Alas, it succeeds less well as a playable game. It runs in real time, meaning events can and will run away without a player who isn’t omniscient enough to be in the exact right spot at the exact right time, while its plot is most kindly described as rudimentary — and don’t even get me started on the pixel hunts. Suffice to say that few games in history have screamed “style over substance” louder than this one. Still, in an age hungry for fodder for the latest graphics cards and equally eager for proof that computer games could be as provocative as any other form of media, it did quite well.

By the time of Dark Seed‘s release, Cyberdreams was already working on another game built around the aesthetic of another edgy artist most famous for his contributions to a Ridley Scott film: Syd Mead, who had done the set designs for Blade Runner, along with those of such other iconic science-fiction films as Star Trek: The Motion Picture, TRON, 2010, and the Alien sequel Aliens. CyberRace, the 1993 racing game that resulted from the partnership, was, like its Cyberdreams predecessor, long on visuals and short on satisfying gameplay.

Well before that game was completed — in fact, before even Dark Seed was released — Pat Ketchum had already approached Harlan Ellison to ask whether he could make a game out of his classic short story “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream.” Doing so was, if nothing else, an act of considerable bravery, given not only Ellison’s general reputation but his specific opinion of videogames as “an utter and absolute stupid waste of time.” And yet, likely as much to Ketchum’s astonishment as anyone else’s, he actually agreed to the project. Why? That is best left to Ellison to explain in his own inimitable fashion:

The question frequently asked of me is this: “Since it is common knowledge that you don’t even own a computer on which you could play an electronic game this complex, since it is common knowledge that you hate computers and frequently revile those who spend their nights logging onto bulletin boards, thereby filling the air with pointless gibberish, dumb questions that could’ve been answered had they bothered to read a book of modern history or even this morning’s newspaper, and mean-spirited gossip that needs endless hours the following day to be cleaned up; and since it is common knowledge that not only do you type your books and columns and TV and film scripts on a manual typewriter (not even an electric, but an actual finger-driven manual), but that the closest you’ve ever come to playing an actual computer- or videogame is the three hours you wasted during a Virgin Airlines flight back to the States from the UK; where the hell do you get off creating a high-tech cutting-edge enigma like this I Have No Mouth thing?”

To which my usual response would be, “Yo’ Mama!”

But I have been asked to attempt politeness, so I will vouchsafe courtesy and venture some tiny explication of what the eff I’m doing in here with all you weird gazoonies. Take your feet off the table.

Well, it goes back to that Oscar Wilde quote about perversion: “You may engage in a specific perversion once, and it can be chalked up to curiosity. But if you do it again, it must be presumed you are a pervert.”

They came to me in the dead of night, human toads in silk suits, from this giant megapolitan organization called Cyberdreams, and they offered me vast sums of money — all of it in pennies, with strings attached to each coin, so they could yank them back in a moment, like someone trying to outsmart a soft-drink machine with a slug on a wire — and they said, in their whispery croaky demon voices, “Let us make you a vast fortune! Just sell us the rights to use your name and the name of your most famous story, and we will make you wealthy beyond the dreams of mere mortals, or even Aaron Spelling, our toad brother in riches.”

Well, I’d once worked for Aaron Spelling on Burke’s Law, and that had about as much appeal to me as spending an evening discussing the relative merits of butcher knives with O.J. Simpson. So I told the toads that money was something I had no trouble making, that money is what they give you when you do your job well, and that I never do anything if it’s only for money. ‘Cause money ain’t no thang.

Well, for the third time, they then proceeded to do the dance, and sing the song, and hump the drums, and finally got down to it with the fuzzy ramadoola that can snare me: they said, “Well (#4), you’ve never done this sort of thing. Maybe it is that you are not capable of doing this here now thing.”

Never tell me not to go get a tall ladder and climb it and open the tippy-topmost kitchen cabinet in my mommy’s larder and reach around back there at the rear of the topmost shelf in the dark with the cobwebs and the spider-goojies and pull out that Mason jar full of hard nasty petrified chickpeas and strain and sweat to get the top off the jar till I get it open and then take several of those chickpeas and shove them up my nose. Never tell me that. Because as sure as birds gotta swim an’ fish gotta fly, when you come back home, you will find me lying stretched out blue as a Duke Ellington sonata, dead cold with beans or peas or lentils up my snout.

Or, as Oscar Wilde put it: “I couldn’t help it. I can resist anything except temptation.”

And there it is. I wish it were darker and more ominous than that, but the scaldingly dopey truth is that I wanted to see if I could do it. Create a computer game better than anyone else had created a computer game. I’d never done it, and I was desirous of testing my mettle. It’s a great flaw with me. My only flaw, as those who have known me longest will casually attest. (I know where they live.)

Having entered the meeting hoping only to secure the rights to Ellison’s short story, Pat Ketchum thus walked away having agreed to a full-fledged collaboration with the most choleric science-fiction writer in the world, a man destined to persist forevermore in referring to him simply as “the toad.” Whether this was a good or a bad outcome was very much up for debate.

Ketchum elected to pair Ellison with David Sears, a journalist and assistant editor for Compute! magazine who had made Cyberdreams’s acquaintance when he was assigned to write a preview of Dark Seed, then had gone on to write the hint book for the game. Before the deal was consummated, he had been told only that Cyberdreams hoped to adapt “one of” Ellison’s stories into a game: “I was thinking, oh, it could be ‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman,’ or maybe ‘A Boy and His Dog,’ and it’s going to be some kind of RPG or something.” When he was told that it was to be “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream,” he was taken aback: “I was like, what? There’s no way [to] turn that into a game!” In order to fully appreciate his dismay, we should look a bit more closely at the story in question.

Harlan Ellison often called “No Mouth” “one of the ten most-reprinted stories in the English language,” but this claim strikes me as extremely dubious. Certainly, however, it is one of the more frequently anthologized science-fiction classics. Written “in one blue-white fit of passion,” as Ellison put it, “like Captain Nemo sitting down at his organ and [playing] Toccata and Fugue in D Minor,” it spans no more than fifteen pages or so in the typical paperback edition, but manages to cram quite a punch into that space.

The backstory entails a three-way world war involving the United States, the Soviet Union, and China and their respective allies, with the forces of each bloc controlled by a supercomputer in the name of maximal killing efficiency. That last proved to be a mistake: instead of merely moving ships and armies around, the American computer evolved into a sentient consciousness and merged with its rival machines. The resulting personality was twisted by its birthright of war and violence. Thus it committed genocide on the blighted planet’s remaining humans, with the exception of just five of them, which it kept alive to physically and psychologically torture for its pleasure. As the story proper opens, it’s been doing so for more than a century. Our highly unreliable narrator is one of the victims, a paranoid schizophrenic named Ted; the others, whom we meet only as the sketchiest of character sketches, are named Gorrister, Benny, Ellen (the lone woman in the group), and Nimdok. The computer calls itself AM, an acronym for its old designation of “Allied Mastercomputer,” but also a riff on Descartes: “I think, therefore I AM.”

The story’s plot, such as it is, revolves around the perpetually starving prisoners’ journey to a place that AM has promised them contains food beyond their wildest dreams. It’s just one more of his cruel jokes, of course: they wind up in a frigid cavern piled high with canned food, without benefit of a can opener. But then something occurs which AM has failed to anticipate: Ted and Ellen finally accept that there is only one true means of escape open to them. They break off the sharpest stalactites they can find and use them to kill the other three prisoners, after which Ted kills Ellen. But AM manages to intervene before Ted can kill himself. Enraged at having his playthings snatched away, he condemns the very last human on Earth to a fate more horrific even than what he has already experienced:

I am a great soft jelly thing. Smoothly rounded, with no mouth, with pulsing white holes filled by fog where my eyes used to be. Rubbery appendages that were once my arms; bulks rounding down into legless humps of slippery matter. I leave a moist trail when I move. Blotches of diseased, evil gray come and go on my surface, as though light is being beamed from within.

Outwardly: dumbly, I shamble about, a thing that could never have been known as human, a thing whose shape is so alien a travesty that humanity becomes more obscene for the vague resemblance.

Inwardly: alone. Here. Living under the land, under the sea, in the belly of AM, whom we created because our time was badly spent and we must have known unconsciously that he could do it better. At least the four of them are safe at last.

AM will be the madder for that. It makes me a little happier. And yet… AM has won, simply… he has taken his revenge…

I have no mouth. And I must scream.

Harlan Ellison was initially insistent that the game version of No Mouth preserve this miserably bleak ending. He declared himself greatly amused by the prospect of “a game that you cannot possibly win.” Less superciliously, he noted that the short story was intended to be, like so much of his work, a moral fable: it was about the nobility of doing the right thing, even when one doesn’t personally benefit — indeed, even when one will be punished terribly for it. To change the story’s ending would be to cut the heart out of its message.

Thus when poor young David Sears went to meet with Ellison for the first time — although Cyberdreams and Ellison were both based in Southern California, he himself was still working remotely from his native Mississippi — he faced the daunting prospect of convincing one of the most infamously stubborn writers in the world — a man who had spent decades belittling no less rarefied a character than Gene Roddenberry over the changes to his “City on the Edge of Forever” script — that such an ending just wouldn’t fly in the contemporary games market. The last company to make an adventure game with a “tragic” ending had been Infocom back in 1983, and they’d gotten so much blow back that no one had ever dared to try such a thing again. People demanded games that they could win.

Much to Sears’s own surprise, his first meeting with Ellison went very, very well. He won Ellison’s respect almost immediately, when he asked a question that the author claimed never to have been asked before: “Why are these [people] the five that AM has saved?” The question pointed a way for the game of No Mouth to become something distinctly different from the story — something richer, deeper, and even, I would argue, more philosophically mature.

Ellison and Sears decided together that each of AM’s victims had been crippled inside by some trauma before the final apocalyptic war began, and it was this that made them such particularly delightful playthings. The salt-of-the-earth truck driver Gorrister was wracked with guilt for having committed his wife to a mental institution; the hard-driving military man Benny was filled with self-loathing over his abandonment of his comrades in an Asian jungle; the genius computer scientist Ellen was forever reliving a brutal rape she had suffered at the hands of a coworker; the charming man of leisure Ted was in reality a con artist who had substituted sexual conquest for intimacy. The character with by far the most stains on his conscience was the elderly Nimdok, who had served as an assistant to Dr. Josef Mengele in the concentration camps of Nazi Germany.

You the player would guide each of the five through a surreal, symbolic simulacrum of his or her checkered past, helpfully provided by AM. While the latter’s goal was merely to torture them, your goal would be to cause them to redeem themselves in some small measure, by looking the demons of their past full in the face and making the hard, selfless choices they had failed to make the first time around. If they all succeeded in passing their tests of character, Ellison grudgingly agreed, the game could culminate in a relatively happy ending. Ellison:

This game [says] to the player there is more to the considered life than action. Television tells you any problem can be solved in 30 minutes, usually with a punch in the jaw, and that is not the way life is. The only thing you have to hang onto is not your muscles, or how pretty your face is, but how strong is your ethical behavior. How willing are you to risk everything — not just what’s convenient, but everything — to triumph. If someone comes away from this game saying to himself, “I had to make an extremely unpleasant choice, and I knew I was not going to benefit from that choice, but it was the only thing to do because it was the proper behavior,” then they will have played the game to some advantage.

Harlan Ellison and David Sears were now getting along fabulously. After several weeks spent working on a design document together, Ellison pronounced Sears “a brilliant young kid.” He went out of his way to be a good host. When he learned, for example, that Sears was greatly enamored with Neil Gaiman’s Sandman graphic novels, he called up said writer himself on his speakerphone: “Hi, Neil. This is David. He’s a fan and he’d love to talk to you about your work.” In retrospect, Ellison’s hospitality is perhaps less than shocking. He was in fact helpful and even kind throughout his life to young writers whom he deemed to be worth his trouble. David Sears was obviously one of these. “I don’t want to damage his reputation because I’m sure he spent decades building it up,” says Sears, “but he’s a real rascal with a heart of gold — but he doesn’t tolerate idiots.”

The project had its industry coming-out party at the seventh annual Computer Game Developers Conference in May of 1993. In a measure of how genuinely excited Harlan Ellison was about it, he agreed to appear as one of the most unlikely keynote speakers in GDC history. His speech has not, alas, been preserved for posterity, but it appears to have been a typically pyrotechnic Ellison rant, judging by the angry response of Computer Gaming World editor Johnny L. Wilson, who took Ellison to be just the latest in a long line of clueless celebrity pundits swooping in to tell game makers what they were doing wrong. Like all of the others, Wilson said, Ellison “didn’t really understand technology or the challenges faced daily by his audience [of game developers].” His column, which bore the snarky title of “I Have No Message, but I Must Scream,” went on thusly:

The major thesis of the address seemed to be that the assembled game designers need to do something besides create games. We aren’t quite sure what he means.

If he means to take the games which the assembled designers are already making and infuse them with enough human emotion to bridge the gaps of interpersonal understanding, there are designers trying to accomplish this in many different ways (games with artificial personalities, multiplayer cooperation, and, most importantly, with story).

If he objects to the violence which is so pervasive in both computer and video games, he had best revisit the anarchic and glorious celebration of violence in his own work. Violence is an easy way to express conflict and resolution in any art form. It can also be powerful. That is why we advocate a more careful use of violence in certain games, but do not editorialize against violence per se.

Harlan Ellison says that the computer-game design community should quit playing games with their lives. We think Ellison should stop playing games with his audiences. It’s time to put away his “Bad Melville” impression and use his podium as a “futurist” to challenge his audiences instead of settling for cheap laughs and letting them miss the message.

Harlan Ellison seldom overlooked a slight, whether in print or in person, and this occasion was no exception. He gave Computer Gaming World the rather hilarious new moniker of Video Wahoo Magazine in a number of interviews after Wilson’s editorializing was brought to his attention.

But the other side of Harlan Ellison was also on display at that very same conference. David Sears had told Ellison shortly before he made his speech that he really, really wanted a permanent job in the games industry, not just the contract work he had been getting from Cyberdreams. So, Ellison carried a fishbowl onstage with him, explained to the audience that Sears was smart and creative as heck and urgently needed a job, and told them to drop their business cards in the bowl if they thought they might be able to offer him one. “Three days later,” says Sears, “I had a job at Virgin Games. If he called me today [this interview was given before Ellison’s death] and said, ‘I need you to fix the plumbing in my bathroom,’ I’d be on a plane.”

Ellison’s largess was doubly selfless in that it stopped his No Mouth project in its tracks. With Sears having departed for Virgin Games, it spent at least six months on the shelf while Cyberdreams finished up CyberRace and embarked on a Dark Seed II. Finally Pat Ketchum handed it to a new hire, a veteran producer and designer named David Mullich.

It so happens that we met Mullich long, long ago, in the very early days of these histories. At the dawn of the 1980s, as a young programmer just out of university, he worked for the pioneering educational-software publisher Edu-Ware, whom he convinced to let him make some straight-up games as well. One of these was an unauthorized interactive take on the 1960s cult-classic television series The Prisoner; it was arguably the first commercial computer game in history to strive unabashedly toward the status of Art.

Mullich eventually left Edu-Ware to work for a variety of software developers and publishers. Rather belying his earliest experiments in game design, he built a reputation inside the industry as a steady hand well able to churn out robust and marketable if not always hugely innovative games and educational products that fit whatever license and/or design brief he was given. Yet the old impulse to make games with something to say about the world never completely left him. He was actually in the audience at the Game Developers Conference where Harlan Ellison made his keynote address; in marked contrast to Johnny L. Wilson, he found it bracing and exciting, not least because “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” was his favorite short story of all time. Half a year or so later, Pat Ketchum called Mullich up to ask if he’d like to help Ellison get his game finished. He didn’t have to ask twice; after all those years spent slogging in the trenches of commerce, here was a chance for Mullich to make Art again.

His first meeting with Ellison didn’t begin well. Annoyed at the long delay from Cyberdreams’s side, Ellison mocked him as “another member of the brain trust.” It does seem that Mullich never quite developed the same warm relationship with Ellison that Sears had enjoyed: Ellison persisted in referring to him as “this new David, whose last name I’ve forgotten” even after the game was released. Nonetheless, he did soften his prejudicial first judgment enough to deem Mullich “a very nice guy.” Said nice guy took on the detail work of refining Sears and Ellison’s early design document — which, having been written by two people who had never made a game before, had some inevitable deficiencies — into a finished script that would combine Meaning with Playability, a task his background prepared him perfectly to take on. Mullich estimates that 50 percent of the dialog in the finished game is his, while 30 percent is down to Sears and just 20 percent to Ellison himself. Still, even that level of involvement was vastly greater than that of most established writers who deigned to put their names on games. And of course the core concepts of No Mouth were very much Ellison and Sears’s.

Pat Ketchum had by this point elected to remove Cyberdreams from the grunt work of game development; instead the company would act as a design mill and publisher only. Thus No Mouth was passed to an outfit called The Dreamers Guild for implementation under Mullich’s supervision. That became another long process; the computer game of I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream wasn’t finally released until late 1995, fully three and a half years after Pat Ketchum had first visited Harlan Ellison to ask his permission to make it.

The latter’s enthusiasm for the project never abated over the course of that time. He bestowed his final gift upon David Mullich and the rest of Cyberdreams when he agreed to perform the role of AM himself. The result is one of the all-time great game voice-acting performances; Ellison, a man who loved to hear himself speak under any and all circumstances, leans into the persona of the psychopathic artificial intelligence with unhinged glee. After hearing him, you’ll never be able to imagine anyone else in the role.

Upon the game’s release, Ellison proved a disarmingly effective and professional spokesman for it; for all that he loved to rail against the stupidity of mainstream commercial media, he had decades of experience as a writer for hire, and knew the requirements of marketing. He wrote a conciliatory, generous, and self-deprecatory letter to Computer Gaming World — a.k.a., Video Wahoo Magazine — after the magazine pronounced No Mouth its Adventure Game of the Year. He even managed to remember David Mullich’s last name therein.

With a bewildering admixture of pleasure and confusion — I’m like a meson which doesn’t know which way to quark — I write to thank you and your staff. Pleasure, because everybody likes to cop the ring as this loopy caravanserie chugs on through Time and Space. Confusion, because — as we both know — I’m an absolute amateur at this exercise. To find myself not only avoiding catcalls and justified laughter at my efforts, but to be recognized with a nod of approval from a magazine that had previously chewed a neat, small hole through the front of my face… well, it’s bewildering.

David Sears and I worked very hard on I Have No Mouth. And we both get our accolades in your presentation. But someone else who had as much or more to do with bringing this project to fruition is David Mullich. He was the project supervisor and designer after David Sears moved on. He worked endlessly, and with what Balzac called “clean hands and composure,” to produce a property that would not shame either of us. It simply would not have won your award had not David Mullich mounted the barricades.

I remember when I addressed the Computer Game Designers’ banquet a couple of years ago, when I said I would work to the limits of my ability on I Have No Mouth, but that it would be my one venture into the medium. Nothing has changed. I’ve been there, done that, and now you won’t have to worry about me making a further pest of myself in your living room.

But for the honor you pay me, I am grateful. And bewildered.

Ellison’s acknowledgment of Mullich’s contribution is well-taken. Too often games that contain or purport to contain Deep Meaning believe this gives them a pass on the fundamentals of being playable and soluble. (For example, I might say, if you’ll allow me just a bit of Ellisonian snarkiness, that a large swath of the French games industry operated on this assumption for many years.) That No Mouth doesn’t fall victim to this fallacy — that it embeds its passion plays within the framework of a well-designed puzzle-driven adventure game — must surely be thanks to Mullich. In this sense, then, Sears’s departure came at the perfect time, allowing the experienced, detail-oriented Mullich to run with the grandiose concept which Sears and Ellison, those two game-design neophytes, had cooked up together. It was, one might say, the best of both worlds.

But, lest things start to sound too warm and fuzzy, know that Harlan Ellison was still Harlan Ellison. In the spring of 1996, he filed a lawsuit against Cyberdreams for unpaid royalties. Having spent his life in books and television, it appears that he may have failed to understand just how limited the sales prospects of an artsy, philosophical computer game like this one really were, regardless of how many awards it won. (Witness his comparison of Cyberdreams to the television empire of Aaron Spelling in one of the quotes above; in reality, the two operated not so much in different media galaxies as different universes.) “With the way the retail chain works, Cyberdreams probably hadn’t turned a profit on the game by the time the lawsuit was filed,” noted Computer Gaming World. “We’re not talking sales of Warcraft II here, folks.” I don’t know the details of Ellison’s lawsuit, nor what its ultimate outcome was. But I do know that David Mullich estimates today that No Mouth probably sold only about 40,000 copies in all.

Harlan Ellison didn’t always keep the sweeping promises he made in the heat of the moment; he huffily announced on several occasions that he was forever abandoning television, the medium with which he passed so much of his career in such a deadly embrace, only to be lured back in by money and pledges that this time things would be different. He did, however, keep his promise of never making another computer game. And that, of course, makes the one game he did help to make all the more special. I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream stands out from the otherwise drearily of-its-time catalog of Cyberdreams as a multimedia art project that actually works — works as a game and, dare I say it, as a form of interactive literature. It stands today as a rare fulfillment of the promise that so many saw in games back in those heady days when “multimedia” was the buzzword of the zeitgeist — the promise of games as a sophisticated new form of storytelling capable of the same relevance and resonance as a good novel or movie. This is by no means the only worthwhile thing that videogames can be, nor perhaps even the thing they are best at being; much of the story of gaming during the half-decade after No Mouth‘s release is that of a comprehensive rejection of the vision Cyberdreams embodied. The company went out of business in 1997, by which time its artsy-celebrity-driven modus operandi was looking as anachronistic as Frank Sinatra during the heyday of the Beatles.

Nevertheless, I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream remains one of the best expressions to stem from its confused era, a welcome proof positive that sometimes the starry-eyed multimedia pundits could be right. David Mullich went on to work on such high-profile, beloved games as Heroes of Might and Magic III and Vampire: The Masquerade — Bloodlines, but he still considers No Mouth one of the proudest achievements of a long and varied career that has encompassed the naïvely idealistic and the crassly commercial in equal measure. As well he should: No Mouth is as meaningful and moving today as it was in 1995, a rare example of a game adaptation that can be said not just to capture but arguably to improve on its source material. It endures as a vital piece of Harlan Ellison’s literary legacy.

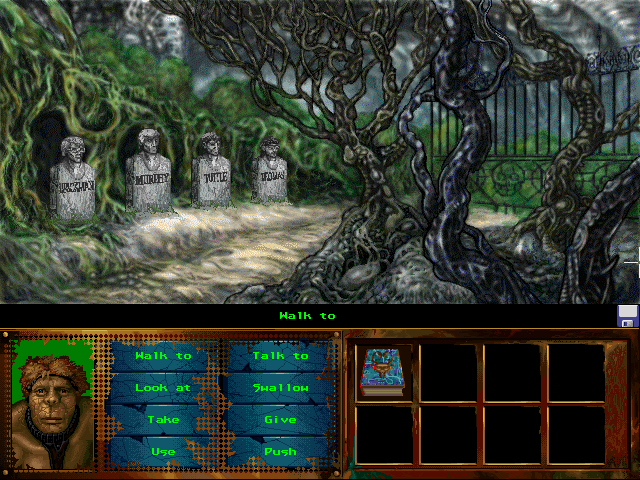

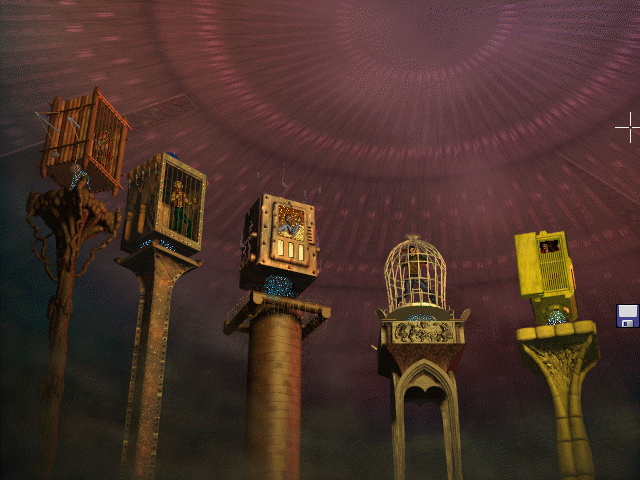

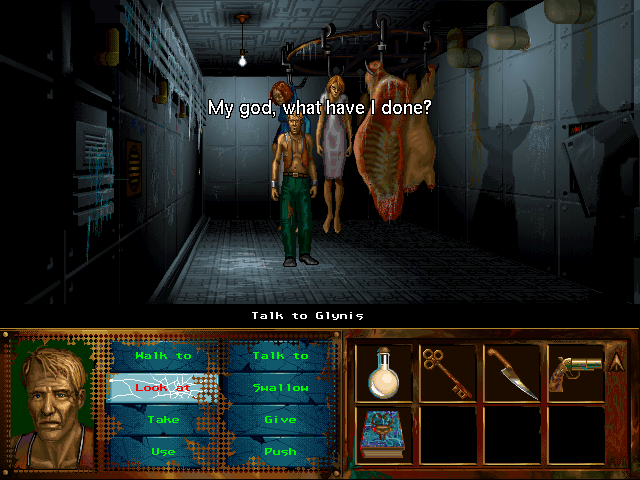

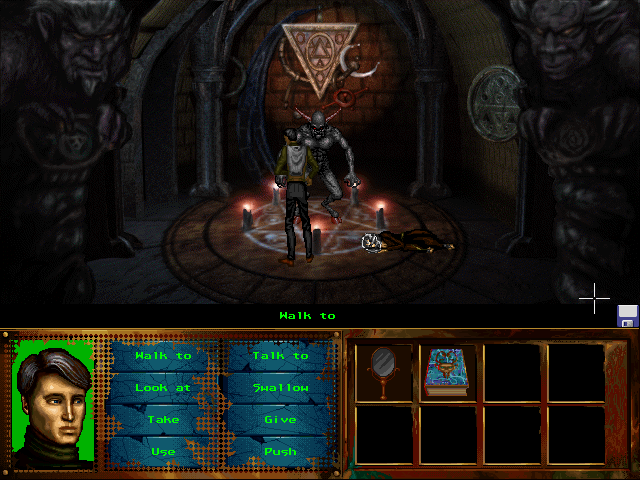

In I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream, you explore the traumas of each of the five people imprisoned by the psychotic supercomputer AM, taken in whatever order you like. Finding a measure of redemption for each of them opens up an endgame which offers the same chance for the rest of humanity — a dramatic departure from the infamously bleak ending of the short story on which the game is based.

Each character’s vignette is a surreal evocation of his tortured psyche, but is also full of opportunities for him to acknowledge and thereby cleanse himself of his sins. Harlan Ellison particularly loved this bit of symbolism, involving the wife and mother-in-law of the truck driver Gorrester: he must literally let the two principal women in his life off the hook. (Get it?) Ellison’s innocent delight in interactions like these amused the experienced game designer David Mullich, for whom they were old hat.

In mechanical terms, No Mouth is a fairly typical adventure game of its period. Its engine’s one major innovation can be seen in the character portrait at bottom left. The background here starts out black, then lightens through progressive shades of green as the character in question faces his demons (literally here, in the case of Ted — the game is not always terribly subtle). Ideally, each vignette will conclude with a white background. Be warned: although No Mouth mostly adheres to a no-deaths-and-no-dead-ends philosophy — “dying” in a vignette just gets the character bounced back to his cage, whence he can try again — the best ending becomes impossible to achieve if every character doesn’t demonstrate a reasonable amount of moral growth in the process of completing his vignette.

The computer genius Ellen is mortified by yellow, the color worn by the man who raped her. Naturally, the shade features prominently in AM’s decor.

If sins can be quantified, then Nimdok, the associate to Dr. Mengele, surely has the most to atone for. His vignette involves the fable of the Golem of Prague, who defended the city’s Jewish ghetto against the pogroms of the late sixteenth century. Asked whether he risked trivializing the Holocaust by putting it in a game, Harlan Ellison answered in the stridently negative: “Nothing could trivialize the Holocaust. I don’t care whether you mention it in a comic book, on bubble-gum wrappers, in computer games, or write it in graffiti on the wall. Never forget. Never forget.“

People say, “Oh, you’re so prolific.” That’s a remark made by assholes who don’t write. If I were a plumber and I repaired 10,000 toilets, would they say, “Boy, you’re a really prolific plumber?”

If I were to start over, I would be a plumber. I tell that to people, they laugh. They think I’m making it up. It’s not funny. I think a plumber, a good plumber who really cares and doesn’t overcharge and makes sure things are right, does more good for the human race in a given day than 50 writers. In the history of the world, there are maybe, what, 20, 30 books that ever had any influence on anybody, maybe The Analects of Confucius, maybe The History of the Peloponnesian Wars, maybe Uncle Tom’s Cabin. If I ever write anything that is remembered five minutes after I’m gone, I will consider myself having done the job well. I work hard at what I do; I take my work very seriously. I don’t take me particularly seriously. But I take the work seriously. But I don’t think writing is all that inherently a noble chore. When the toilet overflows, you don’t need Dostoevsky coming to your house.

That’s what I would do, I would get myself a job as a plumber. I would go back to bricklaying, which I used to do. I would become an electrician. Not an electrical engineer. I would become an electrician. I would, you know, install a night light in a kid’s nursery, and at the end of the day, if I felt like writing, I would write something. I don’t know what that has to do with the game or anything, but you asked so I told you.

— Harlan Ellison (1934-2018)

(Sources: the books The Way the Future Was by Frederick Pohl, These Are the Voyages: Season One by Marc Cushman with Susan Osborn, The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction edited by Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn, I Have No Mouth & I Must Scream: Stories by Harlan Ellison, and I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream: The Official Strategy Guide by Mel Odom; Starlog of September 1977, April 1980, August 1980, August 1984, November 1985, and December 1985; Compute! of November 1992; Computer Gaming World of March 1988, September 1992, July 1993, September 1993, April 1996, May 1996, July 1996, August 1996, November 1996, and June 1999; CU Amiga of November 1992 and February 1993; Next Generation of January 1996; A.N.A.L.O.G. of June 1987; Antic of August 1983; Retro Gamer 183. Online sources include a 1992 Game Informer retrospective on I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream and a history of Cyberdreams at Game Nostalgia. My thanks also go to David Mullich for a brief chat about his career and his work on No Mouth.

I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream is available as a digital purchase at GOG.com.)