If you have to stare at someone’s bum, it’s far better to look at a nice female bum than a bloke’s bum!

— Adrian Smith of Core Design

There was something refreshing about looking at the screen and seeing myself as a woman. Even if I was performing tasks that were a bit unrealistic… I still felt like, hey, this is a representation of me, as myself, as a woman. In a game. How long have we waited for that?

— gamer Nikki Douglas

Sure, she’s powerful and assertive. She takes care of herself, and she knows how to handle a gun. She’s a great role model for girls. But how many copies of Tomb Raider do you think they’d have sold if they’d made Lara Croft flat-chested?

— Charles Ardai, Computer Gaming World

It strikes me that Lara Croft must be the most famous videogame character in history if you take the word “character” literally. Her only obvious competition comes from the Nintendo stable — from Super Mario and Pac-Man and all the rest. But they aren’t so much characters as eternal mascots, archetypes out of time in the way of Mickey Mouse or Bugs Bunny. Lara, on the other hand, has a home, a reasonably coherent personal chronology, a reasonably fleshed-out personality — heck, she even has a last name!

Of course, Lara is by no means alone in any of these things among videogame stars. Nevertheless, for all the cultural inroads that gaming has made in recent decades, most people who don’t play games will still give you a blank stare if you try to talk to them about any of our similarly well-rounded videogame characters. Mention Solid Snake, Cloud, or Gordon Freeman to them and you’ll get nothing. But Lara is another story. After twenty games that have sold almost 100 million copies combined and three feature films whose box-office receipts approach $1 billion, everybody not living under a proverbial rock has heard of Lara Croft. Love her or hate her, she has become one of us in a way that none of her peers can match.

Lara’s roots reach back to the first wave of computer gaming in Britain, to the era when Sinclair Spectrums and Commodore 64s were the hottest machines on the market. In 1984, in the midst of this boom, Ian Stewart and Kevin Norburn founded the publisher Gremlin Graphics — later Gremlin Interactive — in the back room of a Sheffield software shop. Gremlin went on to become the Kevin Bacon of British game development: seemingly everybody who was anybody over the ensuing decades was associated with them at one time or another, or at the very least worked with someone who had been. This applies not least to Lara Croft, that most iconic woman in the history of British gaming.

Core Design, the studio that made her, was formed in 1986 as Gremlin Derby, around the talents of four young men from the same town who had just created the hit game Bounder using the Commodore 64s in their bedrooms. But not long after giving the four a real office to work in, the folks at Gremlin’s Sheffield headquarters began to realize that they should have looked before they leaped — that they couldn’t actually afford to be funding outside studios with their current revenue stream. (Such was the way of things in the topsy-turvy world of early British game development, when sober business expertise was not an overly plentiful commodity.) Rather than close the Derby branch they had barely had time to open, three Gremlin insiders — a sales executive named Jeremy Heath-Smith, the current manager of the Derby studio Greg Holmes, and the original Gremlin co-founder Kevin Norburn — cooked up a deal to take it over and run it themselves as an independent entity. They set up shop under the name of Core Design in 1988.

Over the year that followed, Core had its ups and downs: Heath-Smith bought out Holmes in 1990 and Norburn in 1992, both under circumstances that weren’t entirely amicable. But the little studio had a knack for squeezing out a solid seller whenever one was really needed, such as Rick Dangerous and Chuck Rock. Although most of these games were made available for MS-DOS among other platforms, few of them had much in common with the high-concept adventure games, CRPGs, and strategy games that dominated among American developers at the time. They were rather direct descendants of 8-bit games like Bounder: fast-paced, colorful, modest in size and ambition, and shot through with laddish humor. By 1991, Core had begun porting their games to consoles like the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, with whose sensibilities they were perhaps a more natural fit. And indeed, the consoles soon accounted for the majority of their sales.

In late 1994, Jeremy Heath-Smith was invited to fly out to Japan to check out the two latest and greatest consoles from that country, both of which were due for a domestic Japanese release before the end of that year and an international rollout during the following one. The Sega Saturn and the Sony PlayStation were groundbreaking in a number of ways: not only did they use capacious CDs instead of cramped cartridges as their standard storage media, but they each included a graphics processing unit (GPU) for doing 3D graphics. At the time, id Software’s DOOM was in the vanguard of a 3D insurgency on personal computers, one that was sweeping away older, slower games like so much chaff in the breeze. The current generation of consoles, however, just didn’t have the horsepower to do a credible job of running games like that; they had been designed for another paradigm, that of 2D sprites moving across pixel-graphic backgrounds. The Saturn and the PlayStation would change all that, allowing the console games that constituted 80 to 90 percent of the total sales of digital games to join the 3D revolution as well. Needless to say, the potential payoff was huge.

Back at Core Design in Derby, Heath-Smith told everyone what he had seen in Japan, then asked for ideas for making maximum use of the new consoles’ capabilities. A quiet 22-year-old artist and designer named Toby Gard raised his hand: “I’ve got this idea of pyramids.” You would play a dashing archaeologist, he explained, dodging traps and enemies on the trail of ancient relics in a glorious 3D-rendered environment.

It must be said that it wasn’t an especially fresh or unexpected idea in the broad strokes. Raiders of the Lost Ark had been a constant gaming touchstone almost from the moment it had first reached cinemas in 1981. Core’s own Rick Dangerous had been essentially the same game as the one that Gard was now proposing, albeit implemented using 2D sprites rather than 3D graphics. (Its titular hero there was a veritable clone of the Raiders‘s hero Indiana Jones, right down to his trademark whip and fedora; if you didn’t read the box copy, you would assume it was a licensed game.)

Still, Gard was enthusiastic, and possessed of “immense talent” in the opinion of Heath-Smith. His idea certainly had the potential to yield an exciting 3D experience, and Heath-Smith had been around long enough to know that originality in the abstract was often overrated when it came to making games that sold. He gave Tomb Raider the green light to become Core’s cutting-edge showcase for the next-generation consoles, Core’s biggest, most expensive game to date. Which isn’t to say that he could afford to make it all that big or expensive by the standards of the American and Japanese studios: a team of just half a dozen people created Tomb Raider.

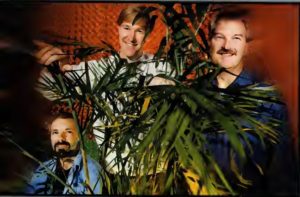

The Tomb Raider team. Toby Gard is third from left, Jeremy Heath-Smith second from right. Heather Gibson was the sole woman to work on the game — which, to be fair, was one more woman than worked on most games from this period.

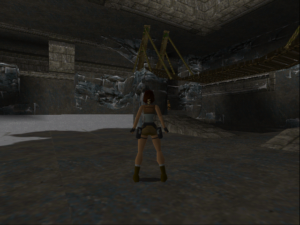

The game would depart in a significant way from the many run-and-gun DOOM clones on personal computers by being a bit less bloody-minded, emphasizing puzzle-solving and platforming as much as combat. The developers quickly decided that the style of gameplay they had in mind demanded that they show the player’s avatar onscreen from a behind-the-back view rather than going with the first-person viewpoint of DOOM — an innovative choice at the time, albeit one that several other studios were making simultaneously, with such diverse eventual results as Fade to Black, Die Hard Trilogy, Super Mario 64, and MDK. In the beginning, though, they had no inkling that it would be Lara Croft’s bum the player would be staring at for hours. The star was to be Rick Dangerous or another of his ilk — i.e., just another blatant clone of Indiana Jones.

But Heath-Smith was seasoned enough to know that that sort of thing wouldn’t fly anymore in a world in which games were becoming an ever bigger and more visible mass-media phenomenon. “You must be insane,” he said to Toby Gard as soon as he heard about his intended Indiana clone. “We’ll get sued from here to kingdom come!” He told him to go back to the drawing board — literally; he was an artist, after all — and create a more clearly differentiated character.

So, Gard sat down at his desk to see what he could do. He soon produced the first sketches of Lara — Lara Cruz, as he called her in the beginning. Gard:

Lara was based on Indiana Jones, Tank Girl, and, people always say, my sister. Maybe subconsciously she was my sister. Anyway, she was supposed to be this strong woman, this upper-class adventurer. The rules at the time were, if you’re going to make a game, make sure the main character is male and make sure he’s American; otherwise it won’t sell in America. Those were the rules coming down from the marketing men. So I thought, “Ah, I know how to fix this. I’ll make the bad guys all American and the lead character female and as British as I can make her.”

She wasn’t a tits-out-for-the-lads type of character in any way. Quite the opposite, in fact. I thought that what was interesting about her was, she was this unattainable, austere, dangerous sort of person.

Sex appeal aside, Lara was in tune with the larger zeitgeist around her in a way that few videogames characters before her could match. Gard first sketched her during the fall of 1995, when Cool Britannia and Britpop were the rages of the age in his homeland, when Oasis and Blur were trash-talking one another and vying for the top position on the charts. It was suddenly hip to be British in a way it hadn’t been since the Swinging Sixties. Bands like the aforementioned made a great point of singing in their natural accents — or, some would say, an exaggerated version of same — and addressing distinctly British concerns rather than lapsing into the typical Americanisms of rock and pop music. Lara was cut from the same cloth. Gard changed her last name to “Croft” when he decided “Cruz” just wasn’t British enough, and created a defiantly blue-blooded lineage for her, making her the daughter of a Lord Henshingly Croft, complete with a posh public-school accent.

Jeremy Heath-Smith was not initially impressed. “Are you insane?” he asked Gard for the second time in a month. “We don’t do girls in videogames!” But Gard could be deceptively stubborn when he felt strongly about something, and this was one of those occasions. Heath-Smith remembers Gard telling him that “she’d be bendy. She’d do things that blokes couldn’t do.” Finally, he relented. “There was this whole movement of, females can really be cool, particularly from Japan,” he says.

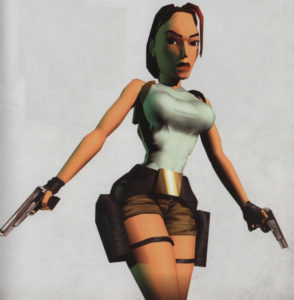

And indeed, Lara was first drawn with a distinctly manga sensibility. Only gradually, as Gard worked her into the actual game, did she take on a more realistic style. Comparatively speaking, of course. We’ll come back to that…

Tomb Raider was becoming ever more important for Core. In the wake of the Sega Saturn and the Sony PlayStation, the videogames industry was changing quickly, in tandem with its customers’ expectations of what a new game ought to look like; there was a lot of space on one of those shiny new CDs, and games were expected to fill it. The pressures prompted a wave of consolidations in Britain, a pooling of a previously diffuse industry’s resources in the service of fewer but bigger, slicker, more expensive games. Core actually merged twice in just a couple of years: first with the US Gold publishing label (its name came from its original business model, that of importing American games into Britain) and then with Domark, another veteran of the 1980s 8-bit scene. Domark began trading under the name of Eidos shortly after making the deal, with Core in the role of its premier studio.

Eidos had as chairman of its board Ian Livingstone, a legend of British gaming in analog spaces, the mastermind of the Warhammer tabletop game and the Fighting Fantasy line of paperback gamebooks that enthralled millions of youth during the 1980s. He went out to have a look at what Core had in the works. “I remember it was snowing,” he says. “I almost didn’t go over to Derby.” But he did, and “I guess you could say it was love at first sight when I stepped through the door. Seeing Lara on screen.”

With such a powerful advocate, Tomb Raider was elevated to the status of Eidos’s showcase game for the Christmas of 1996, with a commensurate marketing budget. But that meant that it simply had to be a hit, a bigger one by far than anything Core had ever done before. And Core was getting some worrisome push-back from Eidos’s American arm, expressing all the same conventional wisdom that Toby Gard had so carefully created Lara to defy: that she was too British, that the pronunciation of her first name didn’t come naturally to American lips, that she was a girl, for Pete’s sake. Cool Britannia wasn’t really a thing in the United States; despite widespread predictions of a second muscial British Invasion in the States to supersede the clapped-out Seattle grunge scene, Oasis had only partially broken through, Blur not at all, and Spice Girls — the latest Britpop sensation — had yet to see their music even released Stateside. Eidos needed another way to sell Lara Croft to Americans.

It may have been around this time that an incident which Toby Gard would tell of frequently in the years immediately after Tomb Raider‘s release occurred. He was, so the story goes, sitting at his computer tweaking his latest model of Lara when his mouse hand slipped, and her chest suddenly doubled or tripled in size. When a laughing Gard showed it to his co-workers in a “look what a silly thing I did!” sort of way, their eyes lit up and they told him to leave it that way. “The technology didn’t allow us to make her [look] visually as we wanted, so it was more of a way of heightening certain things so it would give her some shape,” claims Core’s Adrian Smith.

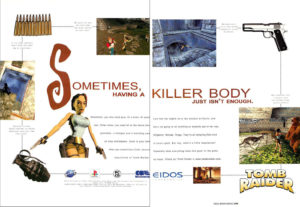

Be that as it may, Eidos’s marketing team, eying that all-important American market that would make or break this game that would make or break their company, saw an obvious angle to take. They plastered Lara, complete with improbably huge breasts and an almost equally bulbous rear end, all over their advertising. “Sometimes, having a killer body just isn’t enough,” ran a typical tagline. “Hey, what’s a little temptation? Especially when everything looks this good. In the game, we mean.” As for the enemies Lara would have to kill, “Not everyone sees a bright light just before dying. Lucky stiffs.” (The innuendo around Lara was never subtle…)

This, then, was the way that Lara Croft greeted the public when her game dropped in September of 1996. And Toby Gard hated it. Giving every indication of having half fallen in love with his creation, he took the tarting up she was receiving under the hands of Eidos’s marketers badly. He saw them rather as a young man might the underworld impresario who had convinced his girlfriend — or his sister? — to become a stripper. A suggestion that reached Core’s offices to include a cheat code to remove Lara’s clothing entirely was, needless to say, not well-received by Gard. “It’s really weird when you see a character of yours doing these things,” he says. “I’ve spent my life drawing pictures of things — and they’re mine, you know?”

But of course they weren’t his. As is par for the course in the games industry, Gard automatically signed over all of the rights to everything he made at Core just as soon as he made it. He was not the final arbiter of what Lara did — or what was done to her – from here on out. So, he protested the only way he knew how: he quit.

Jeremy Heath-Smith, whose hardheaded businessman’s view of the world was the polar opposite of Gard’s artistic temperament, was gobsmacked by the decision.

I just couldn’t believe it. I remember saying, “Listen, Toby, this game’s going to be huge. You’re on a commission for this, you’re on a bonus scheme, you’re going to make a fortune. Don’t leave. Just sit here for the next two years. Don’t do anything. You’ll make more money than you’ve ever seen in your life.” I’m not arty, I’m commercial. I couldn’t understand his rationale for giving up millions of pounds for some artistic bloody stand. I just thought it was insanity.

Heath-Smith’s predictions of Tomb Raider‘s success — and with them the amount of money Gard was leaving on the table — came true in spades.

Suspecting every bit as strongly as Heath-Smith that they had a winner on their hands, Eidos had already flown a lucky flock of reporters all the way to Egypt in August of 1996 to see Tomb Raider in action for the first time, with the real Pyramids of Giza as a backdrop. By now, the Sega Saturn and the Sony PlayStation had been out for a year in North America and Europe, with the PlayStation turning into by far the bigger success, thanks both to Sony’s superior marketing and a series of horrific unforced errors on Sega’s part. Nevertheless, Tomb Raider appeared first on the Saturn, thanks to a deal Eidos had inked which promised Sega one precious month of exclusivity in return for a substantial cash payment. Rather than reviving the fortunes of Sega’s moribund console, Tomb Raider on the Saturn wound up serving mostly as a teaser for the PlayStation and MS-DOS versions that everyone knew were waiting in the wings.

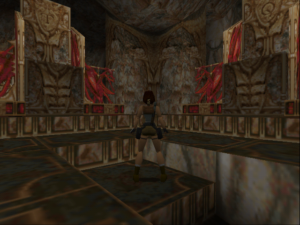

The game still has qualities to recommend it today, although it certainly does show its age in some senses as well. The plot is barely comprehensible, a sort of Mad Libs of Raiders of the Lost Ark, conveyed in fifteen minutes of cut scenes worth of pseudo-mystical claptrap. The environments themselves, however, are possessed of a windy grandeur that requires no exposition, with vistas that can still cause you to pull up short from time to time. If nothing else, Tomb Raider makes a nice change of pace from the blood-splattered killing fields of the DOOM clones. In the first half of the game, combat is mostly with wildlife, and is relatively infrequent. You’ll spend more of your time working out the straightforward but satisfying puzzles — locked doors and hidden keys, movable boulders waiting to be turned into staircases, that sort of thing — and navigating vertigo-inducing jumps. In this sense and many others, Tomb Raider is more of an heir to the fine old British tradition of 8-bit action-adventures than it is to the likes of DOOM. Lara is quite an acrobat, able to crouch and spring, flip forward and backward and sideways, swim, climb walls, grab ledges, and when necessary shoot an arsenal of weapons that expands in time to include shotguns and Uzis alongside her iconic twin thigh-holstered pistols.

Amidst all the discussion of Lara Croft’s appearance, a lot of people failed to notice the swath she cuts through some of the world’s most endangered species of wildlife. “The problem is that any animal that’s dangerous to humans we’ve already hunted to near extinction,” said Toby Gard. “Maybe we should have used non-endangered, harmless animals. Then you’d be asking me, ‘Why was Lara shooting all those nice bunnies and squirrels?’ You can’t win, can you?”

Unfortunately, Tomb Raider increasingly falls prey to its designers’ less worthy instincts in its second half. As the story ups the stakes from just a treasure-hunting romp to yet another world-threatening videogame conspiracy, the environments grow less coherent and more nonsensical in rhythm, until Lara is battling hordes of mutant zombies inside what appears for all the world to be a pyramid made out of flesh and blood. And the difficulty increases to match, until gameplay becomes a matter of die-and-die-again until you figure out how to get that one step further, then rinse and repeat. This is particularly excruciating on the console versions, which strictly ration their save points. (The MS-DOS version, on the other hand, lets you save any time you like, which eases the pain considerably.) The final gauntlet you must run to escape from the last of the fifteen levels is absolutely brutal, a long series of tricky, non-intuitive moves that you have to time exactly right to avoid instant death, an exercise in rote yet split-second button mashing to rival the old Dragon’s Lair game. It’s no mystery why Tomb Raider ended up like this: its amount of content is limited, and it needed to stretch its playing time to justify a price tag of $50 or more. Still, it’s hard not to think wistfully about what a wonderful little six or seven hour game it might have become under other circumstances, if it hadn’t needed to fill fifteen or twenty hours instead.

Tomb Raider‘s other weaknesses are also in the predictable places for a game of this vintage, a time when designers were still trying to figure out how to make this style of game playable. (“Everyone is sitting down and realizing that it’s bloody hard to design games for 3D,” said Peter Molyneux in a contemporaneous interview.) The controls can be a little awkward, what with the way they keep changing depending on what Lara’s actually up to. Ditto the distractingly flighty camera through which you view Lara and her environs, which can be uncannily good at finding exactly the angle you don’t want it to at times. Then, too, in the absence of a good auto-map or clear line of progression through each level, you might sometimes find orientation to be at least as much a challenge as any of the other, more deliberately placed obstacles to progress.

Games would slowly get better at this sort of thing, but it would take time, and it’s not really fair to scold Tomb Raider overmuch for failings shared by virtually all of the 3D action games of 1996. Tomb Raider is never less than a solidly executed game, and occasionally it becomes an inspired one; your first encounter with a Tyrannosaurus Rex (!) in a lost Peruvian valley straight out of Arthur Conan Doyle remains as shocking and terrifying today as it ever was.

As a purely technical feat, meanwhile, Tomb Raider was amazing in its day from first to last. The levels were bigger than any that had yet been seen outside the 2.5D Star Wars shooter Dark Forces. In contrast to DOOM and its many clones, in contrast even to id’s latest 3D extravaganza Quake, Tomb Raider stood out as its own unique thing, and not just because of its third-person behind-the-back perspective. It just had a bit more finesse about it all the way around. Those other games all relied on big bazooka-toting lunks with physiques that put Arnold Schwarzenegger to shame. Even with those overgrown balloons on her chest, Lara managed to be lithe, nimble, potentially deadly in a completely different way. DOOM and Quake were a carpet-bombing attack; she was a precision-guide missile.

Sex appeal and genuinely innovative gameplay and technology all combined to make Lara Croft famous. Shelley Blond, who voiced Lara’s sharply limited amount of dialog in the game, tells of wandering into a department store on a visit to Los Angeles, and seeing “an enormous cutout of Lara Croft. Larger than live-size.” She made the mistake of telling one of the staff who she was, whereupon she was mobbed like a Beatle in 1964: “I was bright red and shaking. They all wanted pictures, and that was when I thought, ‘Shit, this is huge!'”

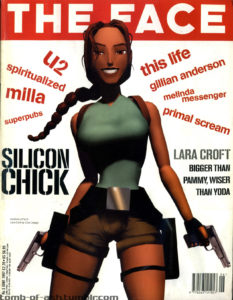

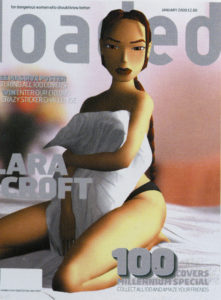

In a landmark moment for the coming out of videogames as a force in mainstream pop culture, id Software had recently convinced the hugely popular industrial-rock band Nine Inch Nails to score Quake. But that was nothing compared to the journey that Lara Croft now made in the opposite direction, from the gaming ghetto into the mainstream. She appeared on the cover of the fashion magazine The Face: “Occasionally the camera angle allows you a glimpse of her slanted brown eyes and luscious lips, but otherwise Lara’s always out ahead, out of reach, like the perfect girl who passes in the street.” She was the subject of feature articles in Time, Newsweek, and Rolling Stone. Her name got dropped in the most unlikely places. David James, the star goalkeeper for the Liverpool football club, said he was having trouble practicing because he’d rather be playing Tomb Raider. Rave-scene sensations The Prodigy used their addiction to the game as an excuse for delaying their new album. U2 commissioned huge images of her to show on the Jumbotron during their $120 million Popmart tour. She became a spokeswoman for the soft drink Lucozade and for Fiat cars, was plastered across mouse pads, CD-wallets, and lunch boxes. She became a kids’ action figure and the star of her own comic book. It really was as if people thought she was an actual person; journalists clamored to “interview” her, and Eidos was buried in fan mail addressed to her. “This was like the golden goose,” says Heath-Smith. “You don’t think it’s ever going to stop laying. Everything we touched turned gold. It was just a phenomenon.” Already in 1997, negotiations began for an eventual Tomb Raider feature film.

Most of all, Lara was the perfect mascot for the PlayStation. Sony’s most brilliant marketing stroke of all had been to pitch their console toward folks in their late teens and early twenties rather than children and adolescents, thereby legitimizing gaming as an adult pursuit, something for urban hipsters to do before and/or after an evening out at the clubs. (It certainly wasn’t lost on Sony that this older demographic tended to have a lot more disposable income than the younger ones…) Lara may have come along a year too late for the PlayStation launch, but better late than never. What hipster videogaming had been missing was its very own It Girl. And now it had her. Tomb Raider sold seven and a half million copies, at least 80 percent of them on the PlayStation.

That said, it did very well for itself on computers as well, especially after Core posted on their website a patch to make the game work with the new 3Dfx Voodoo chipset for hardware-accelerated 3D graphics on that platform. Tomb Raider drove the first wave of Voodoo adoption; countless folks woke up to find a copy of the game alongside a shiny new graphics card under the tree that Christmas morning. Eidos turned a £2.6 million loss in 1996 into a £14.5 million profit in 1997, thanks entirely to Lara. “Eidos is now the house that Lara built,” wrote Newsweek magazine.

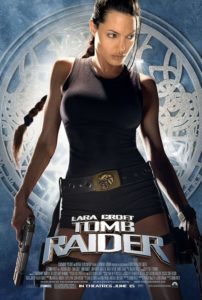

There followed the inevitable sequels, which kept Lara front and center through the balance of the 1990s and beyond: Tomb Raider II in 1997, Tomb Raider III in 1998, Tomb Raider: The Last Revelation in 1999, Tomb Raider: Chronicles in 2000. These games were competently done for the most part, but didn’t stretch overmuch the template laid down by the first one; even the forthrightly non-arty Jeremy Heath-Smith admits that “we sold our soul” to keep the gravy train running, to make sure a new Tomb Raider game was waiting in stores each Christmas. Just as the franchise was starting to look a bit tired, with each successive game posting slowly but steadily declining sales numbers, the long-in-the-works feature film Lara Croft: Tomb Raider arrived in 2001 to bring her to a whole new audience and ensure that she became one of those rare pop-culture perennials.

By this time, a strong negative counter-melody had long been detectable underneath the symphony of commercial success. A lot of people — particularly those who weren’t quite ready to admit videogames into the same halls of culture occupied by music, movies, and books — had an all too clear image of who played Tomb Raider and why. They pictured a pimply teenage boy or a socially stunted adult man sitting on the couch in his parents’ basement with one hand on a controller and another in his pants, gazing in slack-jawed fascination at Lara’s gyrating backside, perhaps with just a trace of drool running down his spotty chin. And it must be admitted that some of Lara’s biggest fans didn’t do much to combat this image: the site called Nude Raider, which did what Toby Gard had refused to do by patching a naked version of Lara into the game, may just have been the most pathetic thing on the Internet circa 1997.

But other fans leaped to Lara’s defense as something more than just the world’s saddest masturbation aid. She was smart, she was strong, she was empowered, they said, everything feminist critics had been complaining for years that most women in games were not.

The problem, answered Lara’s detractors, was that she was still all too obviously crafted for the male gaze. She was, in other words, still a male fantasy at bottom, and not a terribly mature one at that, looking as she did like something a horny teenager who had yet to lay hands on a real girl might draw in his notebook. Her proportions — proudly announced by Eidos as 34D-24-35 — were obtainable by virtually no real woman, at least absent the services of a plastic surgeon. “If you genetically engineered a Lara-shaped woman,” noted PC Gaming World‘s (female) reviews editor Cal Jones, “she would die within around fifteen seconds, since there’s no way her tiny abdomen could house all her vital organs.” Violet Berlin, a popular technology commentator on British television, called Lara “a ’70s throwback from the days when pouting lovelies were always to be found propped up against any consumer icon advertised for men.”

Everyone was right in her or his own way, of course. Lara Croft truly was different from the videogame bimbos of the past, and the fact that millions of boys were lining up to become her — or at least to control her — was progress of some sort. But still… as soon as you looked at her, you knew which gender had drawn her. Even Toby Gard, who had given up millions in a purely symbolic protest against the way his managers wished to exploit her, talked about her in ways that were far from free of male gazing — that could start to sound, if we’re being honest, just a little bit creepy.

Lara was designed to be a tough, self-reliant, intelligent woman. She confounds all the sexist clichés apart from the fact that she’s got an unbelievable figure. Strong, independent women are the perfect fantasy girls — the untouchable is always the most desirable.

Some feminist linguists would doubtless make much of the unconscious slip from “women” to “girls” in this comment…

The Lara in the games was rather a cipher in terms of personality, which worked for her benefit in the mass media. She could easily be re-purposed to serve as anything from a feminist hero to a sex kitten, depending on what was needed at that juncture.

For every point there was a counterpoint. Some girls and women saw Lara as a sign of progress, even as an aspirational figure. Others saw her only as one more stereotype of female perfection created by and for males, one to which they could never hope to measure up. “It’s a well-known fact that most [male] youngsters get their first good look at the female anatomy through porn mags, and come away thinking women have jutting bosoms, airbrushed skin, and neatly trimmed body hair,” said Cal Jones. “Now, thanks to Lara, they also think women are super fit, agile gymnasts with enough stamina to run several marathons back to back. Cheers.”

On the other hand, the same male gamers had for years been seeing images of almost equally unattainable masculine perfection on their screens, all bulging biceps and chiseled abs. How was this different? Many sensed that it was different, somehow, but few could articulate why. Michelle Goulet of the website Game Girlz perhaps said it best: Lara was “the man’s ideal image of a girl, not a girl’s ideal image of a girl.” The inverse was not true of all those warrior hunks: they were “based on the body image that is ideal to a lot of guys, not girls. They are nowhere near my ideal man.” The male gaze, that is to say, was the arbiter in both cases. What to do about it? Goulet had some interesting suggestions:

My thoughts on this matter are pretty straightforward. Include females in making female characters. Find out what the ideal female would be for both a man and a woman and work with that. Respect the females the same as you would the males.

Respecting the female characters is hard when they look like strippers with guns and seem to be nothing more than an erection waiting to happen. Believing that the industry in general respects females is hard when you see ads with women tied up on beds. In my opinion, respect is what most girls are after, and I feel that if the gaming community had more respect for their female characters they would attract the heretofore elusive female market. This doesn’t mean that girls in games have to be some kind of new butch race. Femininity is a big part of being female. This means that girls should be girls. Ideal body images and character aspects that are ideal for females, from a female point of view. I would be willing to bet that guys would find these females more attractive than the souped-up bimbos we are used to seeing. If sexuality is a major selling point, and a major attraction for the male gamer, then, fine, throw in all the sexuality you want, but doing so should not preclude respect for females.

To sum up, I have to say I think the gaming industry should give guys a little more credit, and girls a lot more respect, and I hope this will move the tide in that direction.

I’m happy to say that the tide has indeed moved in that direction for Lara Croft at least since Michelle Goulet wrote those words in the late 1990s. It began in a modest way with that first Tomb Raider movie in 2001. Although Angeline Jolie wore prosthetic breasts when she played Lara, it was impossible to recreate the videogame character’s outlandish proportions in their entirety. In order to maintain continuity with that film and a second one that came out in 2003, the Tomb Raider games of the aughts modeled their Laras on Jolie, resulting in a slightly more realistic figure. Then, too, Toby Gard returned to the franchise to work on 2007’s Tomb Raider: Anniversary and 2008’s Tomb Raider: Underworld, bringing some of his original vision of Lara with him.

But the real shift came when the franchise, which was once again fading in popularity by the end of the aughts, was rebooted in 2013, with a game that called itself simply Tomb Raider. Instead of pendulous breasts and booty mounted on spaghetti-thin legs and torso, it gave us a fit, toned, proportional Lara, a woman who looked like she had spent a lot of time and money at the local fitness center instead of the plastic surgeon’s office. If you ask this dirty old male gazer, she’s a thousand times more attractive than the old Lara, even as she’s a healthy, theoretically attainable ideal for a young woman who’s willing to put in some hard hours at the gym. This was proved by Alicia Vikander, the star of a 2018 Tomb Raider movie, the third and last to date; she looked uncannily like the latest videogame Lara up there on the big screen, with no prosthetics required.

Bravo, I say. If the original Lara Croft was a sign of progress in her way, the latest Lara is a sign that progress continued. If you were to say the new Lara is the one we should have had all along — within the limits of what the technology of the time would allow, of course — I wouldn’t argue with you. But still… better late than never.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

(Sources: The books Grand Thieves and Tomb Raiders: How British Video Games Conquered the World by Magnus Anderson and Rebecca Levene; From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and Computer Games, edited by Justine Cassell and Henry Jenkins; Beyond Barbie and Mortal Kombat: New Perspectives on Gender and Gaming, edited by Yasmin B. Kafai, Carrie Heeter, Jill Denner, and Jennifer Y. Sun; Gender Inclusive Game Design: Expanding the Market by Sheri Graner Ray; The Making of Tomb Raider by Daryl Baxter; 20 Years of Tomb Raider: Digging Up the Past, Defining the Future by Meagan Marie; and A Gremlin in the Works by Mark James Hardisty. Computer Gaming World of August 1996, October 1996, January 1997, March 1997, and November 1997; PC Powerplay of July 1997; Next Generation of May 1996, October 1996, and June 1998; The Independent of April 18 2004; Retro Gamer 20, 147, 163, and 245. Online sources include three pieces for the Game Studies journal, by Helen W. Kennedy, Janine Engelbrecht, and Esther MacCallum-Stewart. Plus two interview with Toby Gard, by The Guardian‘s Greg Howson and Game Developer‘s David Jenkins.

The first three Tomb Raider games are available as digital purchases at GOG.com, as are the many games that followed those three.)