I’ve already devoted a couple of articles to the early history of Cinemaware, the American publisher and developer whose games anticipated the future of interactive multimedia entertainment. I plan to continue that history in later articles.

This, however, isn’t quite one of those articles, even if it does touch upon the next title in our ongoing Cinemaware chronology. Rather than the story of that game, this is the story of the man who created it — a man whose pain-wracked yet extraordinary life demands a little pause for thought. It may serve as a welcome reminder that the story of games is ultimately the story of the real people who make and play them. Escapism is no escape, only a temporary reprieve. In the end we all have to wrestle with the big questions of our own reality — questions of Life and Death and Love and Hate and God — whether we want to or not. Because none of us — no, not even you, over there in the back with the game controller in your hand — gets out of this life alive.

Once again the day came when the members of the court of heaven took their places in the presence of God, and Satan was with them. God asked him where he had been. “Ranging over the earth,” Satan said, “from end to end.” Then God asked Satan, “Have you noticed my servant Job? You will find no one else like him on earth: blameless and upright, fearing God and setting his face against evil. You incited me to ruin him without good reason, but his integrity is still unshaken.”

Satan answered, “Skin for skin! There is nothing that fellow will grudge to save himself. But stretch out your hand and touch his bone and his flesh, and see if he will not curse you to your face.”

Then God said, “All right, then. All that he has is now in your hands, but you must spare his life.”

— The Book of Job

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disease for which there is still no cure. One aspect of the body’s delicate internal balance, the regulators that govern mucus production, is out of whack in the sufferer. What begins as a tendency to contract respiratory infections and a general frailness during childhood progresses at different rates in different cases to a body that is drowning in its own mucus. If the lungs don’t fail first, the pancreas eventually will. When that happens, the patient, unable to produce the digestive enzymes necessary to break down her food, can starve to death no matter how much she stuffs in her mouth. While there is no cure, there are various complicated treatments that can delay the inevitable. Today a cystic-fibrosis sufferer may make it as far as age 50. In earlier decades — the disease was only first definitively identified in 1938 — that number was drastically less.

As a genetic disease, cystic fibrosis is passed down via a defective gene most commonly found in people of Northern European extraction. Each person carries two copies of the gene in question, of which only one need be correct to enjoy a healthy, normal life. Thus most carriers of the disease have no idea of their status. For a child to be born with cystic fibrosis, two carriers or full-blown sufferers — although cases of the latter having children are extremely rare, as infertility in males is an almost universal common side-effect of the disease — must be the parents. Even then, in the case of two healthy carriers as parents the risk of the child being born with the disease is only one in four.

The parents of Bill Williams experienced a run of bad luck of Biblical proportions. Unwitting carriers before marrying and having children, all three of their offspring were born with the disease. The two eldest, a boy and a girl, died in childhood. The last was little Bill, born in 1960 in Pontiac, Michigan, and promptly pronounced by his doctors as unlikely to reach age 13.

Right from the beginning, then, Bill’s experience of time, his very view of his life, was different from that of the rest of us. We are born in hope. We spend our childhood and adolescence dreaming of becoming or doing, and if we are diligent and bold we gradually achieve some of those early dreams, or others that we never quite knew we had. Then, when we reach a certain age, we begin to make peace with our life as it is, with the things we’ve done and with those that we never will. Perhaps we learn at last to accept and enjoy our life as it is rather than how we wish it could be. And then, someday, the final curtain falls.

But what of Bill, born with the knowledge that he would likely never see adulthood, much less a reflective old age? How must it affect him to hear his classmates discussing college funds, hopes and dreams for travel, for love, for that shiny new Porsche or that shiny new Bunny found inside a father’s Playboy? “I never thought I’d have a job or a spouse, or a house, or anything that most little boys think is their birthright,” he later remembered.

As a boy with no future and thus no need to choose a direction in life for himself, Bill learned from an early age how it felt to always have things done to him rather than doing for himself. His own body was never quite his own, being treated as a laboratory by the doctors who, yes, hoped to keep him alive as long as possible, but who also wanted him for the more horrifyingly impersonal task of learning from his illness.

Many of those diagnostics were scary and incomprehensible to a small child: tubes, wires and circling graphs, dark little closets with windows. I remember being surrounded by terrifying tangles of equipment, isolated from my family, hearing beeps and hisses. I remember hating the pulmonary-function machine.

“Why do I have to sit in the pressure chamber again?”

“Because…”

“Why do I have to have another enema, doctor?”

“Because…”

So you lie down and take it.

The doctors’ curiosity only grew when, unlike his two siblings, Bill didn’t die as they had expected. Indeed, apart from the death sentence always hanging over his head and the endless hours spent in doctors’ offices, his childhood was almost normal. For some time he could even run and play like other children.

One day whilst sitting in a doctor’s office awaiting yet another round of tests, Bill met another boy with cystic fibrosis, one who wasn’t so blessedly free of the disease’s worst symptoms as he was at the time. As he watched the boy cough and gag into a thick wad of Kleenex, his reaction was… disgust. He felt toward the boy the anger the healthy sometimes can’t help but feel toward the sick, as if they are the way they are on purpose. When, soon after, his own cough began to manifest at last, it felt like a divine punishment for his act of judgment that day. He returned to the scene in the waiting room again and again in his memory, cursed with the knowledge of how others must see him.

Bill was now a teenager, afflicted with all of a teenage boy’s usual terror of being perceived as different in the eyes of his peers. As his coughing worsened, he desperately tried to cover up his condition, even though for a cystic-fibrosis sufferer to deliberately choose not to cough is to slowly commit suicide; coughing is actually the most welcome thing in the world, because it gets the mucus that will otherwise drown him up and out. Sometimes he could duck into a restroom when he felt a coughing fit coming on, where he could crouch spitting and puking in privacy over a toilet. But then sometimes his classmates would come in and ask what was wrong: “Should I call someone?” Those times were the worst because of the curse Bill bore of being able to see himself through their eyes. He started to swallow cough drops by the handful, poisoning himself and stripping his tooth enamel away right down to the gum line; the dentist whom he would finally visit in his twenties would say he had never seen so much erosion in anyone’s mouth before.

He found solace and camaraderie only with the burnouts, the kids in the torn denims out smoking in the school parking lot — even though smoking or even being around smokers was pretty much the stupidest thing a cystic-fibrosis sufferer could do. “They had no ambition, they knew they were on the outside,” he later wrote. “They had been told in various ways that they would never amount to much. We had something in common!”

Together with the burnouts, he got into punk rock, the sound of powerlessness empowered. He formed a band with three of his friends. They called themselves “Sons of Thunder,” and made a glorious racket in dives all around Detroit. Philip, the guitarist, had a 900-watt amp that made as much noise as “a jet taking off,” as Bill later remembered it, giving the whole band a lifelong case of tinnitus. But no matter; that was the least of Bill’s health problems. He played keyboards and screamed himself raw on the mic. His music restored his voice in the metaphorical sense even as it destroyed it in the literal. He exorcised his pain and frustration — at the world, at himself, at God — via many of his own compositions.

They’ll find me in the morning,

With a razor in my hand,

My faded jeans stained with scarlet blood,

The aftermath of slashing pain,

That cut my cord of life and,

Tore all the fibers that it could.If you’ve read the papers lately,

Only good kids die.

I wonder where the others are,

And where their bodies lie.

Maybe they’ve been buried,

In some field far away,

Forgotten, faded memories,

Of tainted yesterdays.I had a dream last night,

Filled me with fright that dream.

In that dream,

God spoke to me:“I hated you,

From the day you were conceived.

From that point on,

I had decided you’d bleed.

Now you stand before me,

On your judgment day.

I need no excuses.

I’ll just throw you away, away.”

One morning in town, he lapsed into one of his coughing fits, whereupon an old busybody started to lecture him on taking better care of himself, wrapping up properly, etc. If he had done that, she said, he wouldn’t have that awful cough. The old Bill would have listened dutifully and slunk away in shame. The new Bill replied, “No, actually it isn’t a cold, it’s a terminal disease that causes a progressive deterioration of the lungs, no matter how I dress… and thank you very much for reminding me of that fact. I’d almost forgotten it for a second.” Powerlessness empowered.

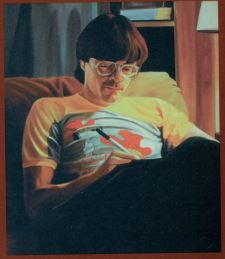

Making music led to making computer programs. Trying to find new sounds for the band, Bill bought a synthesizer kit that included a programmable controller built around the MOS 6502, one of the two little 8-bit chips that made the PC revolution. Despite having no technical training whatsoever, he discovered a “weird affinity” for 6502 assembly language. His father, an engineer with General Motors, was eager for him to find a more stable line of work than screaming himself hoarse every night in bars, and therefore bought him an Atari 800 with the understanding that he would use it to develop some software tools that might prove useful in GM’s factories.

He never got very far with that project. Instead he started working on a game. It felt like coming home. “Computer-game designer,” he came to believe, was somehow inscribed into his very genes, just as much an indelible part of who he was as his cystic fibrosis: “It was my destiny.” His first game was a little thing called Salmon Run (1982), in which the player had to guide a salmon upstream, dodging waterfalls, bears, seagulls, and fishermen all the while, to arrive at the spawning grounds where True Love and Peace awaited. Sweet and simple as it was, it already bore all the hallmarks of a Bill Williams game: nonviolent, laden with metaphor, subtly subversive, and thoroughly original. He was, he would come to realize, “the computer equivalent of an art-folk singer: I couldn’t write a pop hit if my life depended on it.”

Bill had written Salmon Run on a lark, just for fun. But one day he saw an advertisement for a unique new Atari division called The Atari Program Exchange, which promised to publish — paying actual royalties and everything! — the best programs submitted to them by talented amateurs like Bill. He jumped at the chance. Salmon Run was not only accepted, but became one of the Atari Program Exchange’s most popular games, as well as Bill’s own entrée into the industry. Softline magazine, impressed by Salmon Run‘s many and varied sound effects, came to him to write a monthly column on Atari sound programming. And then Ihor Wolosenko came calling from Synapse Software, a company that was making a name for itself as the master of Atari 8-bit action games.

Alley Cat (1983), one of the three games that Bill wrote for Synapse, is his most accessible and enduring game of all, with a cult following of fans to this day. Impossibly cute without ever being cloying, it casts you as the titular tomcat seeking his One True Love (sensing a theme?). Unfortunately, she’s one of those sheltered inside cats, trapped inside her owner’s apartment. To reach her you have to run a gauntlet of garbage cans, fences, clotheslines, and felicitously feline minigames: stealing fish from a human, stealing milk from dogs, catching mice, knocking over vases.

In 1984, Ihor Wolosenko wrangled for Bill an early prototype of the Commodore Amiga, along with a development deal to die for from Commodore themselves. Desperate for software for their forthcoming machine, they would let Bill develop any game he wanted: “No specifications whatsoever. Complete creative freedom.” He found the Amiga rather terrifying at first — “Oh, my God, what have I got myself into?” — but soon came to see its connection to the Atari 8-bit machines he was used to; Jay Miner had designed the chipsets for both machines. “It was like picking up a conversation with someone who had been thinking for a couple of years and had figured out a lot more stuff,” he later said.

Bill had grown entranced by the new scientific field of chaos theory, an upending of the old Newtonian assumptions of a mechanistic, predictable universe into something more enigmatic, more artistic, more, well, chaotic — and possibly admitting of more spiritual possibility as well. In a chaotic world, there is no Platonic ideal of which everything around us is an imperfect shadow. There is only diversity, a riot of real beauty greater than any theoretical idea of perfection. For a man like Bill, whose own body’s systems were so different from those of the people around him, the idea was oddly comforting. He spent months curating little organic worlds inside the Amiga, grown from randomness, noise, and fractal equations, whilst Wolosenko fretted over his lack of tangible progress in making a concrete game out of his experiments. Bill could spend hours “cloud-watching” inside his worlds: “Oh, that one looks like…” What he saw there was as different from the structured, ordered, Newtonian virtual world of the typical computer game as “a snowflake is from a billiard ball.”

The game that finally resulted from his explorations made this landscape of Bill’s imagination into the landscape of the broken mind of a physics professor. To restore him to sanity, you must reconnect the four shards of his personality — Strong Man, Wizard, Spriggan, and Water Nymph — and clear out Bad Thoughts using your Fractal Ray. By the time Bill was finished Synapse Software was no more, so Commodore themselves released the game as Mind Walker (1986), the first and only Amiga game to appear under the platform’s parent’s own imprint and one of the first commercial games to appear for the Amiga at all. Heady, dense, and unabashedly artsy, it fit perfectly with the Amiga’s early image as an idealized dream machine opening up new vistas — literal vistas in Mind Walker‘s case — of possibility. Whether it really qualifies as a great or even good game to, you know, play is perhaps more up to debate, but then one could say the same about many a Bill Williams creation.

Having long since retired from his band to write games full-time, Bill was now beginning to do quite well for himself. By the metrics by which our society usually judges such things, these would prove to be the most successful years of his life; his yearly income would top $100,000 several times during the latter 1980s. His disease was still in relative abeyance. Friends and colleagues who weren’t aware of the complicated rituals he had to go through before and after facing them each day could almost forget that he wasn’t healthy like they were — unless and until he lapsed into one of his uncontrollable coughing fits, that is. Best of all, he now had for a wife an extraordinary woman who loved him dearly. Martha had come into his life around the time of his first computer, and would stand by him, working to keep him as mentally and physically healthy as he could be, for the rest of his days.

Through an old colleague from Synapse, Bill was put in touch with Bob Jacob, just in the process of starting Cinemaware. Along with Doug Sharp, Bill was signed to become one of Cinemaware’s two lone-wolf developers, given carte blanche to independently create a game based on the movies without being actually being based on a movie; the newly formed Cinemaware was hardly in a position to negotiate licenses. Bob had plenty of ideas: “Bob is a generation older, and he would be recommending movies that were more the stuff that really jazzed him when he was twelve or so. I knew if I didn’t come up with a counter-idea, I was going to have to do one of his.” A big fan of the stop-motion visual effects of Ray Harryhausen, Bill settled on an homage to the 1958 adventure classic The 7th Voyage of Sinbad.

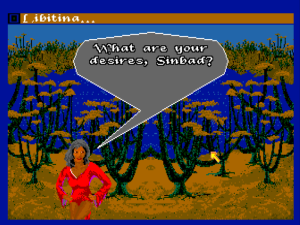

Bill’s Cinemaware game didn’t turn out to be terribly satisfying for either designer or player. While plenty of his games might be judged failures to one degree or another, the others at least failed on their own terms. Sinbad and the Throne of the Falcon (1987) marked the first time that Bill seemed to forfeit some of his own design sensibility in trying to please his client. It attempts, like most Cinemaware games, to marry a number of disparate genres together. And, also like many other Cinemaware games, the fit is far from seamless. Whilst trekking over a large map as Sinbad, talking with other characters and collecting the bits and pieces you need to solve the game, you also have to contend with occasional action games and a strategic war game to boot. None of the game’s personalities are all that satisfying — the world to be explored is too empty, the action and strategy games alike too clunky and simplistic — and taken in the aggregate give the whole experience a bad case of schizophrenia.

Sinbad also attracted criticism for its art. Created like every other aspect of the game by Bill himself, I’ve heard it described on one occasion as “gorgeous folk art,” but more commonly as garish and a little ugly. Suffice to say that it’s a long, long way from Jim Sachs’s lush work on Defender of the Crown. It didn’t help the Amiga original’s cause when Cinemaware themselves ported the game in-house to other platforms, complete with much better art. Nothing was more certain to get Amiga users up in arms than releasing Atari ST and even Commodore 64 versions of a game that looked better than the Amiga version.

Libitina of Sinbad and the Throne of the Falcon, the most painfully pixelated of all Cinemaware’s trademark love/lust interests.

Bill himself was less than thrilled with Sinbad when all was said and done, recognizing that he had lost his own voice to some extent out of a desire to please his publisher. He agreed to do sound programming for two more Cinemaware games, as he had for Defender of the Crown before Sinbad‘s release, but backed away from the relationship thereafter.

As a palate cleanser from the big, ambitious Sinbad — or, as the musically-minded Bill liked to put it, as his Get Back project — he wrote a simple top-down shooter called Pioneer Plague (1988). Published by the tiny label Terrific Software, its big technical gimmick was that it ran in HAM, the Amiga’s unique graphics mode that allowed the programmer to place all 4096 colors on the screen at once. Pioneer Plague marked the first time that anyone had seen HAM, normally used only for still images because of its slowness and awkwardness to program, in an action game. Not for nothing did Bill have a reputation among the Amiga faithful as a technically masterful programmer’s programmer.

Bill’s next and, as it would transpire, last game for the Amiga would prove the most time-consuming and frustrating of his career. He called it Knights of the Crystallion (1990).

Knights was the game I threw the most of my soul into, out of all the games I ever did. Knights was my attempt to draw the industry into a different direction. It was going to be my epic, it was going to be my masterpiece — we called it a cultural simulation — and I thought I could pull it off.

Such abstracts aside, it’s very hard to describe just what Knights of the Crystallion is or was meant to be, always a dangerous sign when discussing a game. Like Sinbad, it’s a hybrid, and often a baffling one, incorporating action, adventure, resource management, grand strategy, pattern-matching, puzzle-solving, and board games among other, less definable elements. The complicated backstory is drawn from a science-fiction novel Bill had been contemplating writing, the art style from the old Yes album covers of Roger Dean. The package included a cassette of music and 18 pages of poetry — all, like everything in the game proper, created personally by Bill. It was also a game with a message, one that subverted the typical ludic economic model: “I got into designing an economy in which all of the rules necessary to actually doing well provide an economic reward for thinking charitably and being part of the community, rather than selfishly grabbing all of the resources for yourself.”

It was a long way from the days of Salmon Run and Alley Cat — and, one could argue, not entirely for the better. And yet for all that Knights of the Crystallion‘s overstuffed design contained, Bill estimated that “limits of time, machine, publisher” meant that less than 20 percent of what he’d wanted to put in there was in fact present in the finished product.

Neither of Bill’s last two games did very well commercially, and by the time Knights of the Crystallion was finished in late 1990 the Amiga market in general in North America was quite clearly beginning to fade; the latter game was made available only via mail order in its homeland, a far cry from Bill’s high-profile days with Cinemaware. Looking at his dwindling royalty checks, he made the tough decision to abandon the Amiga, and with it his career as a lone-wolf software auteur. He accepted a staff position, his first and only, with a company called Sculptured Software, who were preparing a stable of games for the forthcoming launch of the Super Nintendo console in North America. (Sculptured was ironically the same developer that had failed comprehensively in creating Defender of the Crown for Cinemaware back in 1986, necessitating a desperate effort to rescue the project using other personnel.) Trying to put the best face on the decision, Bill imagined his discovery of the Super Nintendo as another adventure like his discovery of the Amiga, “a black box with a whole bunch of unknowns and a completely new field to play in.” But he was given nothing like the room to explore that Synapse and Commodore had arranged for him in the case of Mind Walker. Instead a series of disheartening licensed properties came down the pipeline, each exhaustively specified, monitored, and sanitized by the management of Sculptured, the management of Nintendo, and the management of whatever license happened to be in play. It wasn’t quite the way this art-folk singer of software was used to working. Something called The Simpsons: Bart’s Nightmare (1993) — Bill promptly started referring to it as “Bill’s Nightmare” — proved the last straw. He walked off the project when it was “92 percent” complete, ending his career as a maker of games in order to take the most surprising and remarkable step of his life.

The change had begun with Martha. In the early years of their relationship, Bill affectionately called her “Pollyanna” because of what he took to be her naive faith in a God who “liked matter, still cared for body and soul, still actively loved the world.” How could she believe in a benign God in the face of the suffering inflicted upon him and, perhaps even more so, upon his parents, they of the two dead children and the other who was destined not to live very long? But, observing Martha’s steadfast faith as the years passed, he began to question whether he wasn’t the naive, unsophisticated, ungrateful one. There’s an old saying that God never allows more suffering than we can handle. Looking back on his own life, he saw, apart from that great central tragedy of cystic fibrosis, a multitude of benign serendipities.

I “just happened” to build a synthesizer kit that “just happened” to have an optional computer controller; “just happened” to discover a weird affinity for 6502 machine code, which “just happened” to be the heart of the first home videogame system; “just happened” to do a game for my own enjoyment and “just happened” to see an ad from a new Atari division, looking for products… and “just happened” to discover a career that could be done at home, at my own body’s pace and schedule. The royalties, savings, and disability insurance I “just happened” to make from that career just happen to feed us to this day.

One day, after being married to Martha for several years, my eyes were opened, and I saw what I had rather than what I feared I would not have. In fact, I had to admit that none of my fears had panned out. I kept waiting for doom to fall, and bounty kept falling instead.

It’s all just a trick of the eyesight, you know. It all depends on what you’re looking for. As a new acquaintance of mine, Ed Rose, has remarked, you can just as well ask why good happens in the world. In the worst of situations — he served in Vietnam — good keeps breaking out with insane persistence.

Maybe we need a doctrine of Original Charity to balance the weight of Original Sin. Correct the assumptions. In a universe where all the facts seem to point to evolutionary aggression, self-interest, and evil, maybe we need to start wondering why this place isn’t worse, rather than better.

By the time these realizations were breaking through Bill had spent years living a life typical of his profession, “uncomfortable around people,” forever “spelunking his own caverns” inside the computer. For Bill, the life of the technical ascetic had a particular appeal. He had virtually since birth regarded his body as his enemy. The computer provided an escape from his too, too solid flesh. He spent twelve or sixteen hours many days in front of the screen; Martha saw only the back of his head most days.

It’s a symptom — perhaps a blessing? — of the human condition that we all live as if we’re immortal, happily squandering the precious hours of our lives on trivialities. But, noted Bill — echoing in the process the sentiments of another famed game designer — “when you’re dying, no one looks back and says, ‘My God, I wish I’d spent more time at the office.'” In the long term, of course, we’re all dying. But Bill’s long term was much shorter than most.

To say that the life of a chronic-disease sufferer is a hard one is to state the obvious, but the full spectrum of the pain it brings may be less obvious. There’s the guilt that comes with the knowledge that your loved ones are suffering in their own right every day as well from your illness, and the sneaking, dangerous suspicion that knowledge carries with it that everyone would be better off if you would just die already. And accompanying the guilt is the shame. Why can’t you just get better, like everyone wants you to? What did it say about the young Bill when his parents took him to church and the whole congregation prayed for him and the next day he still had cystic fibrosis? Was he not worthy of God’s grace? To suffer from a genetic disease isn’t like battling an infection from outside, but rather to have something fundamentally wrong with the very structure of you. Bill felt a profound connection to other marginalized people of any sort, those who suffered or who saw their horizons limited — which is often pretty much the same thing, come to think of it — not from anything they had done but from who they were.

And so, perhaps also inspired a bit by the universe of chaotic beauty he had glimpsed inside the virtual world of Mind Walker, he started to open up to the physical world again. He took small steps at first. He volunteered to work in a charity soup kitchen, and he and Martha sponsored a child through Christian Children’s Fund: $25 per month to feed and clothe a fisherman’s son in South America. Writing letters to little Alex, Bill didn’t know how to explain what he did for a living to a boy who had never seen a computer or a computer game. There was something elemental about the concerns of Alex’s life — food, shelter, family, community — that felt lacking in his own. When other people asked him about his job, he caught himself adopting a defensive tone, as if he was “a rep for a tobacco company. And I heard that and I thought, ‘Oh, my God, that’s what you think of yourself?'” So at last he quit to attend seminary in Chicago — to become a pastor, to help people, to connect with life.

It proved the most rewarding thing he had ever done. He spent much time counseling patients in a hospital, a task to which a lifelong “professional patient” like himself could bring much practical as well as spiritual wisdom. The experience was many things.

It was listening to a gentle, soft-spoken woman tell me how she met her husband, while he lay in a bed and died.

It was listening to inner-city parents tell of their life’s greatest achievement: keeping their kids out of the gangs.

It was being awed and humbled by the faith of everyday people in outrageous circumstances.

It was listening to folks be brave and strong on the outside while the inside crumbled.

It was standing up for meek patients being railroaded into choices they didn’t have to make.

It was spending five minutes talking about the broken body, and two hours talking about the spouse that died last year. I was amazed to discover how poorly our society provides for psychic hurts — and I began to see how the need for help drives people’s health into the ground, just to obtain some socially acceptable caring.

It was hurting with a woman who didn’t want to get out of the hospital because of what was waiting for her at home.

It was days when an odd, risky thought popped into my head… and a patient’s eyes widened in relief and recognition because I’d said it.

It was the dying man who wanted to confess something, but couldn’t. I pronounced a blessing over his head, trying to work in an absolution for what had not been revealed… and felt so very, very small and human.

It was saying the Psalms as prayers for the first time in my life.

It was reviewing events and tearing myself up for hours, both at the hospital and at home.

The city air of Chicago sadly didn’t agree with Bill’s disease. His condition rapidly worsening, he was forced to give up the four-year program after two years. He and Martha moved to Rockport, Texas, where the warm, dry breezes coming off the Gulf of Mexico would hopefully soothe his frazzled lung tissue.

Warm breezes or no, his condition continued to deteriorate. The death he had been cheating since age 13 was quite clearly now approaching. Most of the hours of most days now had to be devoted to his new job, that of simply breathing. He could sleep for no more than two or three hours at a stretch; to sleep longer would be to drown in the mucus that built up inside his lungs. He was now diabetic, and had to take insulin every day. As with many cystic-fibrosis suffers, his strain of diabetes was peculiarly sensitive and ever-changing, meaning he flirted constantly with an insulin coma. (“To avoid the coma I was letting my blood sugars float way too high, which was killing me slowly instead — but frankly, cystic fibrosis is likely to get me before the organ damage is much of an issue. It takes about ten years to show up.”) He had to take a complicated regimen of enzymes each day to digest his food; otherwise he would have starved to death. (“‘Oh, I wish I had that problem,’ dieters have sometimes said to me. No. You don’t.”) He had a permanent catheter embedded in his chest to deliver the constant assault of antibiotics that kept the prospect of an immediately fatal lung infection at bay; the hole in his chest had to be carefully cleaned every week to prevent a fatal infection from that vector instead. He inhaled a drug called Alupent every day that delivered a shock to his system like a “bottled car accident” and hopefully caused him to cough up some of the deadly mucus in his lungs. His colon had been widened by his surgeons to allow the too-solid waste his body produced passage out; despite the re-engineering, constipation would often leave him writhing in “the most potent pain I experience.” He spent much time each day “communing with Flo,” a big tank of bottled oxygen. (“When she starts to work, my legs tingle, my back stops aching, and I stretch as luxuriously as a cat in the sun. Martha laughs at me. She thinks I enjoy it too much.”) And in order to loosen the mucus inside his lungs he got to endure percussion therapy every day — otherwise known as a righteous beating about the chest and back from Martha that undoubtedly hurt her more than it did him. (A cystic-fibrosis in-joke: “It’s a little perk I get from marrying him. How many women have their husbands ask them for a beating?”) Unable to breathe for very long standing up, he spent most of his days and nights sprawled out on a couch with a 9-degree slope, perfectly calibrated to maximize his air intake.

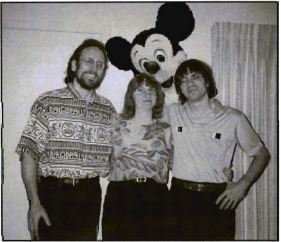

Bill Williams (right), Martha Williams, and a friend in a snapshot taken shortly before Bill’s death.

Despite it all, Bill Williams continued to create. He had a special desk rigged up for his 9-degree couch, and, his days in front of a computer now long behind him, wrote out his final creation with a pencil in longhand. Naked Before God: The Return of a Broken Disciple (1998) is a 132,000-word last testament to his suffering and his joy, to his faith and his doubt. Like the books of the Bibilical prophets on which it’s modeled, it’s raw, knotty, esoteric, and often infuriatingly elliptical. It is, in other words, a classic Bill Williams creation. This isn’t the happy-clappy religion of the evangelical megachurches any more than it is the ritualized formalism of Catholicism. It’s Christ as his own disciples may have known him, dirty and scared and broken, struggling with doubt and with the immense burden laid upon him — yet finally choosing love over hate, good over evil all the same. Writing the book, Bill said, was like undergoing “a theological meltdown.” “It was a near thing,” he wrote at the end, “but I’m still a Christian.” Whatever our personal takes on matters spiritual, we have to respect his lived faith, formed in the crucible of a short lifetime filled with far more than its fair share of pain.

Since he had been a child, Bill had persevered through all the travails of his disease largely for others: first for his parents, who might not be able to bear losing yet another child; later for Martha as well. “My love,” he said, “is the tether that keeps this balloon tied to earth, even when I’d rather just float away.” As he thought about leaving his wife now, the concerns that popped into his head might have sounded banal, but were no less full of love for that. How would she work the computer without him? Would she be able to do their… woops, her taxes?

This final period of his life was, like that of any terminally ill person, a slow negotiation with death on the part of not just the patient but also those who loved him. As Bill watched Martha, he could see the dawning acceptance of his death in her, as gratifying as it was heartbreaking. One day after another of his increasingly frequent seizures, she quietly said the words that every dying person needs, perhaps above all others, to hear. She told him that he was free to slip the tether next time, if he was ready. She would be okay.

Bill Williams died on May 28, 1998, one day shy of his 38th birthday. “I was pretty privileged,” he said of his life at the last. “I really lucked out.”

(This article is drawn from a retrospective of Bill Williams’s career published in the February 1998 and March 1998 issues of Amazing Computing, and most of all from his own last testament Naked Before God. Sinbad and the Throne of the Falcon is available as part of a Cinemaware anthology on Steam.)