Voyager tends to be overlooked in almost every survey because we didn’t really fit into anybody’s category. Librarians didn’t really pay much attention. The computer world never cared. Hollywood never really cared. We touched all these industries, but because we weren’t central to any of them and didn’t really ally with any of them in particular, we were in fact always an outlier.

— Bob Stein

In 1945, Vannevar Bush, an advisor to the American government on the subjects of engineering and technology, published his landmark essay “As We May Think,” which proposed using a hypothetical machine called the memex for navigating through an information space using trails of association. In the decades that followed, visionaries like Ted Nelson adapted Bush’s analog memex to digital computers, and researchers at Xerox PARC developed point-and-click interfaces that were ideal for the things that were by now being called “hypertexts.” Finally, in 1990, Tim Berners-Lee, a British computer scientist working at the European Organization for Nuclear Research in Geneva, created the World Wide Web, which moved hypertext onto the globe-spanning computer network known as the Internet. By the mid-1990s, a revolution in the way that all of us access and understand information was underway.

So runs a condensed history of the most life-changing invention in the realm of information transmission and retrieval since Gutenberg’s printing press. But, like any broad overview, it leaves out the many nooks and crannies where some of the interesting stories and artifacts can be found.

Tim Berners-Lee himself has told how the creation of the World Wide Web was more of a process of assembly than invention from whole cloth: “Most of the technologies involved in the Web had been designed already. I just had to put them together.” To wit: a very workable implementation of hypertext, eminently usable by everyday people, debuted on the Apple Macintosh in 1987, two and a half years before the first website went live. Over the course of that period of time, Apple’s HyperCard was used weekly by millions of people. When combined with the first CD-ROM drives, it gave those lucky people their first heady taste of what computing’s future was to hold for everyone. Even long after the Web had started to hum in earnest, locally hosted experiences, created in HyperCard and similar middleware environments like The Director, were able to combine hypertext with the sort of rich multimedia content that wouldn’t be practical over an Internet connection until after the millennium. This was the brief heyday of the CD as a publishing medium in its own right, a potential rival to the venerable paper-based book.

These CD-based hypertexts were different from the Web in some other, more fundamental or even philosophical ways than that of mere audiovisual fidelity. The Web was and is a hyper-social environment, where everyone links to everyone else — where, indeed, links and clicks are the very currency of the realm. This makes it an exciting, dynamic place to explore, but it also has its drawbacks, as our current struggles with online information bubbles and conscious disinformation campaigns illustrate all too well. Hypertextual, multimedia CD-ROMs, on the other hand, could offer closed but curated experiences, where a single strong authorial voice could be preserved. They were perhaps as close as we’ve ever come to non-fiction electronic books: not paper books which have simply been copied onto an electronic device, like ebooks on the Amazon Kindle and its ilk, but books which could not possibly exist on paper — books which supplement their text whenever necessary with sound and video, books consciously designed to be navigated by association. How strange and sad it is to think that they only existed during a relatively brief interstitial period in the history of information technology, when computers could already deliver hypertext and rich multimedia content but before the World Wide Web was widely enough available and fast enough to do everything we might ask of it.

The gold standard for electronic books on CD-ROM were the ones published by the Voyager Company. These productions ooze personality and quality, boasting innovative presentations and a touching faith in the intelligence of their readers. I would go so far as to say that there’s been no other collection of works quite like them in the entire history of electronic media. They stand out for me as some of my most exciting discoveries in all the years I’ve been writing these chronicles of our recent digital past for you. I’m delighted to bring you their story today.

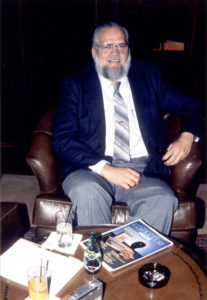

The founder and head of Voyager was one Bob Stein. He was surely one of the most unlikely chief executives in the annals of American business, a man immortalized by Wired magazine as both “the most far-out publishing visionary in the new world” and “the least effective businessman alive.”

Stein was born in New York City in 1946, the son of a wealthy jewelry importer. His upbringing was, as he described it to me, “extremely privileged,” with all the best schools and opportunities that his parents’ money could buy. In high school, he imagined becoming an accountant or a lawyer. But he wound up going to Columbia University as a psychology undergraduate instead, and there he was swept up in the radical politics of the hippie generation. He found a home in the Revolutionary Communist Party, a group which hewed to the China of Chairman Mao in the internecine split that marked the international communist movement. Stein:

I was a revolutionary. I am not a revolutionary anymore, but, although my ideology has shifted, it hasn’t changed. I think we’re still many, many years away from making a judgment about the [Chinese] Cultural Revolution. Anything that is that broad, that encompasses a billion people over a ten-year period, is going to have so many facets to it. I will go to my grave saying that, from one perspective, the Cultural Revolution was the high point of humanity at the point when it happened. We’d never seen a society that was so good for so many of its people. That doesn’t mean it was good for everybody; intellectuals in particular suffered if they were not onboard with what was happening. And intellectuals are the ones who tell the story. So, a lot of the stories are told by intellectuals who didn’t do well during the Cultural Revolution. It was a hard time in China for a lot of people — but I don’t fault the Chinese for trying. Whether they failed is not as interesting to me as whether they tried.

Stein spent the late 1960s and most of the 1970s as a committed communist revolutionary, even as he was also earning a graduate degree in education from Harvard and working as a teacher and grass-roots community activist. Over the years, however, he grew more and more frustrated as the worldwide communist revolution he had been promised failed to materialize.

By the time I was in my early thirties, it became clear that revolution was much, much further away than I had thought when I signed up, as it were. So I made the extremely selfish decision to go do something else with my life. I did that because I could. With degrees from Columbia and Harvard, the world was my oyster. If a white guy like me wanted to come in from the cold, nobody looked askance. I remember walking down the street in New York with my daughter just after I left the Party, heading to some meeting I had set up with the president of CBS, whom I didn’t know, but I knew how to write a letter. She turned to me and said, “You know, you couldn’t be doing this transition if you didn’t have the background you have.” And that was right. It wasn’t that I had any illusion that I was suddenly doing from the inside what I couldn’t do from the outside, it was that I was going to do something interesting and of value to humanity. I wasn’t making revolution anymore, but I would do things that had social value.

The question, of course, was just what those things should be. To the extent that he was aware of it at all, Stein had been unimpressed by the technological utopianism of organizations like Silicon Valley’s People’s Computer Company and Homebrew Computer Club. As a thoroughgoing Maoist, he had believed that society needed to be remade from top to bottom, and found such thinking as theirs naïve: “I didn’t think you could liberate humanity by doing cool shit on computers.”

Stein’s eureka moment came in the bathroom of the Revolutionary Communist Party’s Propaganda Headquarters in Chicago. (Yes, a place by that name really existed.) Someone had left a copy of BusinessWeek there, presumably to help the party faithful keep tabs on the enemy. In it was an article about MCA’s work on what would become known as the laser disc, the first form of optical media to hit the consumer market; each of the record-album-sized discs was capable of storing up to one hour of video and its accompanying audio on each of its sides. Unlike the later audio-only compact disc, the laser disc was an analog rather than digital storage medium, meaning it couldn’t practically be used to store forms of data other than still and moving images and audio. Nevertheless, it could be controlled by an attached computer and made to play back arbitrary snippets of same. “It just seemed cool to me,” says Stein.

Shortly afterward, he and his wife Aleen Stein left the Party and moved to Los Angeles, where he spent his afternoons in the library, trying to make a plan for his future, and his nights working as a waiter. The potential of random-access optical media continued to intrigue him, leading him in the end into a project for Encyclopedia Britannica.

I failed Physics for Poets; I’ve never been technically oriented. I read an article where the chief scientist for Encyclopedia Britannica talked about putting the entire encyclopedia on a disc. I didn’t realize he meant that you could just do a digital dump; I thought he meant you could put it on there in a way that was interesting. So I wrote a letter to Random House asking if I could buy the rights to the Random House encyclopedia, which I quite liked; it was much less stodgy than the Encyclopedia Britannica.

A friend of mine asked me what I was into these days, and I sent her a copy of the letter, forgetting that her father was on the board of Encyclopedia Britannica. A few weeks later, I got a call from Chuck Swanson, the president of Encyclopedia Britannica. “If you know so much,” he said, “why don’t you come and talk to us?” I didn’t know anything!

I found this guy at the University of Nebraska who had made a bunch of videodiscs for the CIA, and I convinced him to come with me to Chicago to provide the gravitas for the meeting. We did a demo for Chuck Swanson and Charlie Van Doren, who was the head of editorial; he was like a kid in a candy store, he fell in love with this shit. They hired me to go away for a year and write a paper.

Stein was fortunate in having made his pitch at just the right time. Traditional print publishers like Encyclopedia Britannica were just beginning to reckon with the impact that the nascent personal-computer revolution was likely to have on their businesses; at almost the same instant that Stein was having his meeting, no less staid a publishing entity than the Reader’s Digest Corporation was investing $3 million in The Source, one of the first nationwide telecommunications services for everyday computer users. In time, when such things proved to catch on slower than their most wide-eyed boosters had predicted, print publishing’s ardor for electronic media would cool again, or be channeled into such other outlets as the equally short-lived bookware boom in computer games.

Stein’s final paper, which he sent to Encyclopedia Britannica in November of 1981, bore the dizzyingly idealistic title of “Encyclopedia Britannica and the Intellectual Tools of the Future.” He still considers it the blueprint of everything he would do in later years. Indeed, the products which he imagined Encyclopedia Britannica publishing would have fit in very well with the later Voyager CD-ROM catalog: Great Moments in History: A Motion Picture Archive; Please Explain with Isaac Asimov; Space Exploration: Past, Present, and Future; Invention and Discovery: The History of Technology; Everyday Life in the American Past; Origins: Milestones in Archaeological Discovery; Computers: The Mystery Unraveled; A Cultural History of the United States; Britannica Goes to London; The Grand Canyon: A Work in Progress. He pleaded with the company to think in the long term. From the report:

The existing [laser-disc] market is so small that immediate returns can only be minimal. To put this another way, if only the next couple of years are considered, more money can be made by investing in bonds than in videodiscs. On the other hand, the application of a carefully designed program now can minimize risks and put Encyclopedia Britannica in a position to realize impressive profits in a few years when the market matures. Three years from now, when other publishers are scrambling to develop video programs, Encyclopedia Britannica will already have a reputation for excellence and enjoy wide sales as a result. Furthermore, the individual programs we have described are designed to be classics that would be sold for many years.

As we’ll see, this ethic of getting in on the ground floor right now, even though profits might be nonexistent for the nonce, would also become a core part of Voyager’s corporate DNA; it would be a company perpetually waiting for a fondly predicted future when the financial floodgates would open. Encyclopedia Britannica, however, wasn’t interested in chasing unicorns at this time. Stein was paid for his efforts and his report was filed away in a drawer somewhere, never to be heard of again.

But Stein himself no longer had any doubts about what sorts of socially valuable things he wanted to work on. His journey next took him to, of all places, the videogame giant Atari.

At the time, the first wave of videogame mania was in full swing in the United States, with Atari at its epicenter, thanks to their Atari VCS home console and their many hit standup-arcade games. They quite literally had more money than they knew what to do with, and were splashing it around in some surprising ways. One of these was the formation of a blue-sky research group that ranged well beyond games to concern itself with the future of computing and information technology in the abstract. Its star — in fact, the man with the title of Atari’s “Chief Scientist” — was Alan Kay, a famous name already among digital futurists: while at Xerox PARC during the previous decade, he had developed Smalltalk, an object- and network-oriented programming language whose syntax was simple enough for children to use, and had envisioned something he called the Dynabook, a handheld computing device that today smacks distinctly of the Apple iPad. Reading about the Dynabook in particular, Stein decided that Alan Kay was just the person he needed to talk to. Stein:

I screwed up my courage one day and contacted him, and he invited me to come meet him. Alan read the [Encyclopedia Britannica] paper — all 120 pages of it — while we were sitting together. He said, “This is great. This is just what I want to do. Come work with me.”

Stein was joining a rarefied collection of thinkers. About half of Kay’s group consisted of refugees from Xerox PARC, while the other half was drawn from the brightest lights at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Architecture Machine Group, another hotbed of practical and theoretical innovation in computing.

Atari’s corporate offices were located in Silicon Valley, while both Stein and Kay lived in Los Angeles. In a telling testimony to the sheer amount of money at Atari’s disposal, they allowed the two to commute to work every day by airplane. Kay would sit next to Stein on the plane and “talk at me about two things I didn’t really know much about: music and computers. But I knew how to nod, so he thought I was understanding, and kept talking.”

Amidst this new breed of revolutionary dreamers, Stein found himself embracing the unwonted role of the practical man; he realized that he wanted to launch actual products rather than being content to lay the groundwork for the products of others, as most of his colleagues were. He took to flying regularly to New York, where he attempted to interest the executives at Warner Communications, Atari’s parent company, in the ideas being batted around on the other coast. But, while he secured many meetings, nothing tangible came out of them. After some eighteen months, he made the hard decision to move on. Once again, his timing was perfect: he left Atari just as the Great Videogame Crash was about to wreck their business. Less than a year later, Warner would sell the remnants of the company off in two chunks for pennies on the dollar, and Alan Kay’s research group would be no more.

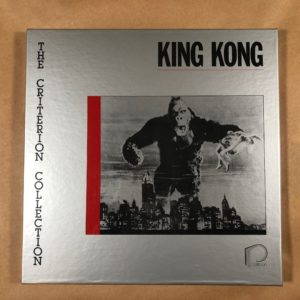

Working independently now, Stein continued to try to interest someone — anyone — in pursuing the directions he had roughed out in his paper for Encyclopedia Britannica and refined at Atari. He got nowhere — until a spontaneous outburst set him on a new course: “At a boring meeting with RKO Home Video, I said off the top of my head, ‘How about selling me a very narrow right to Citizen Kane and King Kong? They said, ‘Sure.'” For the princely sum of $10,000, Stein walked away with the laser-disc rights to those two classic films.

Now all those hours spent hobnobbing with Warner executives paid off. Being idea-rich but cash-poor, Stein convinced a former Warner senior vice president named Roger Smith, who had been laid off in the wake of the Atari implosion, to put up his severance package as the capital for the venture. Thus was formed the Criterion Collection as a partnership between Bob and Aleen Stein and Roger Smith. The name is far better known today than that of Voyager — for, unlike Voyager, Criterion is still going as strong as ever.

The Criterion Citizen Kane and King Kong hit the market in November of 1984, causing quite the stir. For all that our main interest in this article is the later CD-ROMs of Voyager, it’s impossible to deny that, of all the projects Stein has been involved with, these early Criterion releases had the most direct and undeniable influence on the future of media consumption. Among many other innovations, Criterion took advantage of a heretofore little-remarked feature of the laser disc, the ability to give the viewer a choice of audio tracks to go with the video; this let them deploy the first-ever commentary track on the King Kong release, courtesy of film historian and preservationist Ron Haver. Stein describes how it came about:

At that time, and I don’t think it’s all that different today, transferring an old film to video meant sitting in a dark room (which cost hundreds of dollars per hour) making decisions about the correct color values for each individual shot. That was Ron’s job, and somewhat coincidentally, King Kong was his favorite film, and he kept us entertained by telling countless stories about the history of the film’s production. Someone said, “Hey, we’ve got extra sound tracks… why don’t we have Ron tell these stories while the film is playing?” Ron’s immediate reaction was “Are you kidding, NO WAY!” The idea seemed too perfect to pass up, though, so I asked Ron if being stoned might help. He thought for a moment and said, “Hmmm! That might work.” And so the next day we recorded Ron telling stories while the film played.

Criterion also included deleted scenes, making-of documentaries, and other materials in addition to the commentary. In doing so, they laid out what would become standard operating procedure for everyone selling movies for the home once the DVD era arrived twelve years later.

Still, Stein himself believes that the real bedrock of Criterion’s reputation was the quality of the video transfer itself. The Criterion name became a byword for quality, the brand of choice for serious aficionados of film — a status it would never relinquish amidst all the changes in media-consumption habits during the ensuing decades.

So, when Bob Stein dies, his obituary is almost certain to describe him first and foremost as a co-founder of the Criterion Collection, the propagator of a modest revolution in the way we all view, study, and interact with film. Yet Criterion was never the entirety of what Stein dreamed of doing, nor perhaps quite what he might have wished his principal legacy to be. Although he had an appreciation for film, he didn’t burn for it with the same passion evinced by Criterion’s most loyal customers. That description better fit his wife Aleen, who would come to do most of the practical, everyday work of managing Criterion. “I’m a book guy,” he says. “I love books.” The Criterion Collection made quality products of which he was justifiably proud, but it would also become a means to another end, the funding engine that let him pursue his elusive dream of true electronic books.

The company known as Voyager was formed already in 1985, the result of a series of negotiations, transactions, and fallings-out which followed the release of the first two Criterion laser discs. The shakeup began when Roger Smith left the venture, having found its free-wheeling hippie culture not to his taste, and announced his determination to take the Criterion name with him. This prompted the Steins to seek out a new partner in Janus Films, a hallowed name among cineastes, a decades-old art-film distributor responsible for importing countless international classics to American shores. Together they formed the Voyager Company — named after the pair of space probes — to continue what Criterion had begun. Soon, however, it emerged that Smith was willing to sell them back the Criterion name for a not-unreasonable price. So, the logic of branding dictated that the already established Criterion Collection continue as an imprint of the larger Voyager Company.

Stein’s dreams for electronic books remained on hold for a couple of years, while the Criterion Collection continued to build a fine reputation for itself. Then, in August of 1987, Apple premiered a new piece of software called HyperCard, a multimedia hypertext authoring tool that was to be given away free with every new Macintosh computer. Within weeks of HyperCard’s release, enterprising programmers had developed ways of using it to control an attached laser-disc player. This was the moment, says Stein, that truly changed everything.

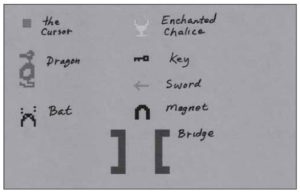

I should note at this juncture that the idea of doing neat things with an ordinary personal computer and an attached laser-disc player was not really a new one in the broad strokes. As far back as 1980, the American Heart Association deployed a CPR-training course built around an Apple II and a laser-disc player. Other such setups were used for pilot training, for early-childhood education, and for high-school economics courses. In January of 1982, Creative Computing magazine published a type-in listing for what was billed as the world’s first laser-disc game, which required a degree of hardware-hacking aptitude and a copy of the laser-disc release of the 1977 movie Rollercoaster to get working. Eighteen months later, laser-disc technology reached arcades in the form of Dragon’s Lair, which was built around 22 minutes of original cartoon footage from the former Disney animator Don Bluth. When the Commodore Amiga personal computer shipped in 1985, it included the ability to overlay its graphics onto other video sources, a feature originally designed with interactive laser-disc applications in mind.

Nevertheless, the addition of HyperCard to the equation did make a major difference for people like Bob Stein. On the one hand, it made controlling the laser-disc player easier than ever before — easy enough even for an avowed non-programmer like him. And on the other hand, hypertexts rather than conventional computer programs were exactly what he had been wanting to create all these years.

Voyager’s first ever product for computers began with an extant laser disc published by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., which included still images of the entirety of the museum’s collection along with scattered video snippets. From this raw material, Stein and two colleagues created the National Gallery of Art Laserguide, a tool for navigating and exploring the collection in a multitude of ways. It caused a big stir at the Macworld Expo in January of 1988: “We became stars! It was fucking magic!” Shortly thereafter, Stein demonstrated it on the television show The Computer Chronicles.

Exciting as experiments like this one were, they couldn’t overcome the inherent drawbacks of the laser disc. As I noted earlier, it was an analog medium, capable of storing only still or moving images and audio. And, as can be seen in the segment above, using it in tandem with a computer meant dealing with two screens — one connected to the computer, the other to the laser-disc player itself. The obvious alternative was the compact disc, a format which, although originally developed for music, was digital rather than analog, and thus could be adapted to store any kind of data and to display it right on a computer’s monitor.

After a tortuously protracted evolution, CD-ROM was slowly sputtering to life as at least a potential proposition for the commercial marketplace. Microsoft was a big booster, having sponsored a CD-ROM conference every year since 1985. The first CD-based software products could already be purchased, although they were mostly uninspiring data dumps targeted at big business and academia rather than the polished, consumer-oriented works Stein aspired to make.

Moving from laser discs to CDs was not an unmitigated positive. The video that an attached laser-disc player could unspool so effortlessly had to be encoded digitally in order to go onto a CD, then decoded and pushed to a monitor in real time by the computer attached to the CD-ROM drive. It was important to keep the file size down; the 650 MB that could be packed onto a CD sounded impressive enough, but weren’t really that much at all when one started using them for raw video. At the same time, the compression techniques that one could practically employ were sharply limited by the computing horsepower available to decompress the video on the fly. The only way to wriggle between this rock and a hard place was to compromise — to compromise dramatically — on the fidelity of the video itself. Grainy, sometimes jerky video, often displayed in a window little larger than a postage stamp, would be the norm with CD-ROM for some time to come. This was more than a little ironic in the context of Voyager, a company whose other arm was so famed for the quality of its movie transfers to laser disc. Suffice to say that no Voyager CD-ROM would ever look quite as good as that National Gallery of Art Laserguide, much less the Criterion King Kong.

Still, it was clear that the necessary future of Voyager were CDs rather than laser discs. Looking for a proof of concept for an electronic book, Stein started to imagine a CD-ROM that would examine a piece of music in detail. He chose that theme, he likes to say only half jokingly, so that he could finally figure out what it was Alan Kay had been going on about in the seat next to his during all those airplane rides of theirs. But there was also another, more practical consideration: it was possible to create what was known as a “mixed mode” CDs, in which music and sound were stored in standard audio-CD format alongside other forms of data. These music tracks could be played back at full home-stereo fidelity by the CD-ROM drive itself, with minimal intervention from the attached computer. This usage scenario was, in other words, analogous to that of controlling an attached laser disc, albeit in this case it was only sound that could be played back so effortlessly at such glorious fidelity.

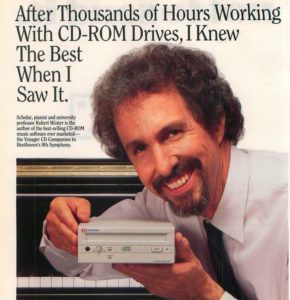

Thus it came to pass that on January 1, 1989, one Robert Winter, a 42-year-old music professor at UCLA, received a visitor at his Santa Monica bungalow: it was Bob Stein, toting an Apple CD-ROM drive at his side. “I thought it was the strangest-looking thing,” Winter says. He had known Stein for some seven years, ever since the latter had sat in on one of his classes, and had often complained to him about the difficulty of writing about music using only printed words on the page; it was akin to “dancing about architecture,” as a famous bit of folk wisdom put it. These complaints had caused Stein to tag him as “a multimedia kind of guy”; “I had no idea what he meant,” admits Winter. But now, Stein showed Winter how an Apple Macintosh equipped with HyperCard and a CD-ROM drive could provide a new, vastly better way of writing about music — by adding to the text the music itself for the reader to listen along with, plus graphics wherever they seemed necessary, with the whole topped off by that special sauce of hypertextual, associative interactivity. The professor took the bait: “I knew then and there that this was my medium.”

Robert Winter became such a star that he was hired by a company called Chinon to pitch their CD-ROM drives.

The two agreed to create a meticulous deconstruction of a towering masterpiece of classical music, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Winter:

I simply asked myself, “What is it I would like to know?” It occurred to me that I would like to know what is happening as the piece is playing. I start [my users] at the bubble-bath level, then the score, then the commentary, and a more detailed commentary.

The heart of the program was the “Close Reading,” where one could read a description of each passage, then listen to it from the same screen — or flip to the score to see what it looked like in musical notation, or flip to a more detailed, technical explanation, always with the chance to listen just a button-click away. Lest the whole experience become too dry, Winter sprinkled it with the wit that had made him a favorite lecturer at his university and a frequent guest commentator on National Public Radio. He equated stability in music with “an apartment you can make the rent on”; conflict in music was “sparring with a boss who doesn’t know how to give strokes.” When it came time for that section of the symphony, the one which absolutely everyone can hum — i..e, the famous “Ode to Joy” — “We’ve arrived!” flashed in big letters on the screen. The text of the poem by Friedrich Schiller which Beethoven set to music for the choir to sing was naturally also included, in the original German and in an English translation. Winter even added a trivia game; answer a question correctly, and Beethoven would wink at you and say, “Sehr gut!” aloud.

“I don’t think anything is any good if it doesn’t have a point of view,” said Bob Stein on one occasion. In being so richly imbued with its maker Robert Winter’s personality and point of view, the CD Companion to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was a model for all of the Voyager CDs to come. “You don’t set his CD-ROMs aside when you’ve exhausted the gimmicks,” wrote Wired magazine of Winter’s interactive works years later. “You keep coming back to them. There always seems to be more intellectual matter – more substance – to uncover.” This too would be the case for Voyager’s CDs in general. They would really, earnestly engage with their subject matter, rather than being content to coast on the novelty of their medium like most of their peers. “It is one of the few producers to offer actual ideas on CD-ROM,” wrote Wired of Voyager itself.

Stein and Winter brought their finished product to the Macworld Expo of August of 1989, where it caused just as much of a sensation as had the National Gallery of Art laser disc nineteen months before. “People stood there for thirty minutes as if they were deer in front of headlights,” says Winter. He claims that many at the show bought CD-ROM drives just in order to run the CD Companion to Beethoven. If it was not quite the first consumer-oriented CD-ROM, it was among the most prominent during the format’s infancy. “We’ve finally seen what CD-ROM was made for!” said Bill Gates upon his first viewing of the program. Like all of its ilk, its initial sales were limited by the expensive hardware needed to run it, but it was written about again and again as an aspirational sign of the times that were soon to arrive. “It takes us up to Beethoven’s worktable and lays bare the whole creative process,” enthused the Los Angeles Herald. Voyager was off and running at last as a maker of electronic books.

Their products would never entirely escape from the aspirational ghetto for a variety of reasons, beginning with their esoteric, unabashedly intellectual subject matter, continuing with the availability of most of them only on the Macintosh (a computer with less than 10 percent of the overall market share), and concluding with the World Wide Web waiting there in the wings with a whole different interpretation of hypertext’s affordances. The CD Companion to Beethoven, which eventually sold 130,000 copies on the back of all the hype and a version for Microsoft Windows,[1]This version bore the title of Multimedia Beethoven. would remain the company’s most successful single product ever; the majority of the Voyager CD-ROMs would never break five digits, much less six, in total unit sales. Yet Stein would manage to keep the operation going for seven years by hook or by crook: by “reinvesting” the money turned over by the Criterion Collection, by securing grants and loans from the Markle Foundation and Apple, and by employing idealistic young people who were willing to work cheap; “If you’re over 30 at Voyager,” said one employee, “you feel like a camp counselor.” Thanks not least to this last factor, the average budget for a Voyager CD-ROM was only about $150,000.

During the first couple of years, Robert Winter’s CD-ROMs remained the bedrock of Voyager; in time, he created explorations of Dvorak, Mozart, Schubert, Richard Strauss, and Stravinsky in addition to Beethoven. By 1991, however, Voyager was entering its mature phase, pushing in several different directions. By 1994, it was publishing more than one new CD per month, on a bewildering variety of subjects.

In the next article, then, we’ll begin to look at this rather extraordinary catalog in closer detail. If any catalog of creative software is worth rediscovering, it’s this one.

(Sources: the book The DVD and the Study of Film: The Attainable Text by Mark Parker and Deborah Parker; Wired of December 1994 and July 1996; CD-ROM Today of June/July 1994; Macworld of November 1988; New York Times of November 8 1992; the 1988 episode of the Computer Chronicles television show entitled “HyperCard”; Phil Salvador’s online interview with Bob Stein. The majority of this article is drawn from a lengthy personal interview with Bob Stein and from his extensive online archives. Thank you for both, Bob!)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | This version bore the title of Multimedia Beethoven. |

|---|