I touched on the history of Brian Fargo and his company Interplay some time ago, when I looked at the impact of The Bard’s Tale, their breakout CRPG hit that briefly replaced the Wizardry series as the go-to yin to Ultima‘s yang and in the process transformed Interplay almost overnight from a minor developer to one of the leading lights of the industry. They deserve more than such cursory treatment, however, for The Bard’s Tale would prove to be only the beginning of Interplay’s legacy. Let’s lay the groundwork for that future today by looking at how it all got started.

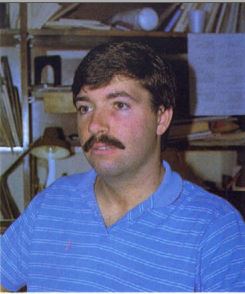

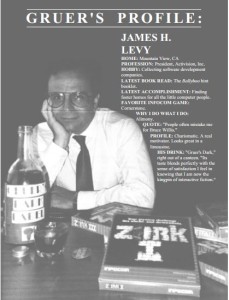

Born into suburban comfort in Orange County, California, in 1962, Brian Fargo manifested from an early age a peculiar genius for crossing boundaries that has served him well throughout his life. In high school he devoured fantasy and science-fiction novels and comics, spent endless hours locked in his room hacking on his Apple II, and played Dungeons and Dragons religiously in cellars and school cafeterias. At the same time, though, he was also a standout athlete at his school, a star of the football team and so good a sprinter that he and his coaches harbored ambitions for a while of making the United States Olympic Team. The Berlin Wall that divides the jocks from the nerds in high school crumbled before Fargo. So it would be throughout his life. In years to come he would be able to spend a day at the office discussing the mechanics of Dungeons and Dragons, then head out for an A-list cocktail party amongst the Hollywood jet set with his good friend Timothy Leary. By the time Interplay peaked in the late 1990s, he would be a noted desirable bachelor amongst the Orange County upper crust (“When he’s not at a terminal he can usually be found rowing, surfing, or fishing”), making the society pages for opening a luxury shoe and accessory boutique, for hosting lavish parties, for planning his wedding at the Ritz-Carlton. All whilst continuing to make and — perhaps more importantly — continuing to openly love nerdy games about killing fantasy monsters. Somehow Brian Fargo made it all look so easy.

But before all that he was just a suburban kid who loved games, whether played on the tabletop, in the arcade, on the Atari VCS, or on his beloved Apple II. Softline magazine, the game-centric spinoff of the voice-of-the-Apple-II-community Softalk, gives us a glimpse of young Fargo the rabid gamer. He’s a regular fixture of the high-score tables the magazine published, excelling at California Pacific’s Apple II knock-off of the arcade game Head-On as well as the swordfighting game Swashbuckler. Already a smooth diplomat, he steps in to soothe a budding controversy when someone claims to have run up a score in Swashbuckler of 1501, a feat that others claim is impossible because the score rolls over to 0 after 255. It seems, Fargo patiently explains, that there are two versions of the game, one of which rolls over and one of which doesn’t, so everyone is right. But the most tangible clue to his future is provided by the question he managed to get published in the January 1982 issue: “How does one get so many pictures onto one disk, such as in The Wizard and the Princess, where On-Line has more than 200 pictures, with a program for the adventure on top of that?” Yes, Brian Fargo the track star had decided to give up his Olympic dream and become a game developer.

By that time Fargo was 19, and a somewhat reluctant student at the University of California, Irvine as well as a repair technician at ComputerLand. No more than an adequate BASIC programmer — he would allow even that ability to atrophy as soon as he could find a way to get someone else to do his coding for him — Fargo knew that he hadn’t a prayer of creating one of the action games that littered Softline‘s high-score rankings, nor anything as complex as Ultima or Wizardry, the two CRPGs currently taking the Apple II world by storm. He did, however, think he might just be up to doing an illustrated adventure game in the style of The Wizard and the Princess. He recruited one Michael Cranford, a Dungeons and Dragons buddy and fellow hacker from high school, to draw the pictures he’d need on paper; he then traced them and colored them on his Apple II. He convinced another friend to write him a few machine-language routines for displaying the graphics. And to make use of it all he wrote a simple BASIC adventure game: you must escape the Demon’s Forge, “an ancient test of wisdom and battle skill.” Desperate for some snazzy cover art, he licensed a cheesecake fantasy print in the style of Boris Vallejo, featuring a shapely woman tied to a pole being menaced by two knights mounted on some sort of flying snakes — this despite a notable lack of snakes (flying or otherwise), scantily-clad females, or for that matter poles in the game proper. (The full Freudian implications of this box art, not to mention the sentence I’ve just written about it, would doubtless take a lifetime of psychotherapy to unravel.)

The Demon’s Forge box art, which won Softline magazine’s sarcastic Relevance in Packaging Award, with Flying-Snakes-and-Ladies-in-Bondage clusters.

Fargo employed a guerrilla-marketing technique that would have made Wild Bill Stealey proud to sell The Demon’s Forge under his new imprint of Saber Software. He took out a single advertisement in Softalk for $2500. Then he started calling stores around the country to ask about his game, claiming to be a potential customer who had seen the advertisement: “A few minutes later my other line would ring and the retailer would place an order.” It didn’t make him big money, but he made a little. Then along came Michael Boone.

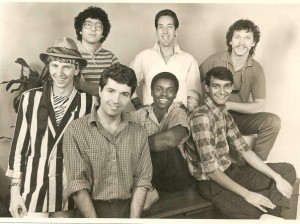

Boone was another old high-school friend, a scion of petroleum wealth who had dutifully gone off to Stanford to study petroleum engineering, only to be distracted by the lure of entrepreneurship. For some time he vacillated between starting a software company and an ice-cream chain, deciding on the former when his family’s connections came through with an injection of venture capital. His long-term plan was to make a golf simulation for the new IBM PC: “IBM seemed like the computer that business people and the affluent were buying. So, I should write a golf game for the IBM computer.” Knowing little about programming and needing some product to get him started, he offered to buy out Fargo’s The Demon’s Forge and his Saber Software for a modest $5000, and have Fargo come work for him. Fargo dropped out of university to do so in late 1982. He assembled a talented little development team consisting of programmers “Burger” Bill Heineman and Troy Worrell along with himself, right there in his and Boone’s hometown of Newport Beach. [1]Bill Heineman now lives as Rebecca Heineman. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times.

Boone Corporation, 1983. Michael Boone is first from left, Bill Heineman second, Troy Worrell fourth, Brian Fargo fifth. They’re toasting with Hires Root Beer. “Hires Root Beer,” “Hi-Res graphics.” Get it?

After porting The Demon’s Forge to the IBM PC, Fargo’s little team occupied themselves writing quick-and-dirty cartridge games like Chuck Norris Superkicks and Robin Hood for the Atari VCS, ColecoVision, and the Commodore VIC-20 and 64. These were published without attribution by Xonox, a spinoff of K-tel Records, one of many dodgy players flooding the market with substandard product during the lead-up to the Great Videogame Crash. Michael Boone agreed to publish under his own imprint a couple of VIC-20 action games — Crater Raider and Cyclon — written by a talented programmer named Alan Pavlish whom Fargo knew well. Meanwhile work proceeded slowly on Boone’s golf simulation for the rich, which was now to be a “tree-for-tree, inch-for-inch recreation of the course at Pebble Beach.” When some Demon’s Forge players called to ask for a hint, Fargo learned that they were part of a company trying to get traction for the Moodies, a bunch of pixieish would-be cartoon characters derivative of the Smurfs; soon they came in to sign a contract for a game to be called Moodies in Iceland.

But then came the Crash. One day shortly thereafter Boone walked into the office and announced that he was taking the company in another direction: to make dry-erase boards instead of computer games. Since Fargo and his team had no particular competency in that field, they were all out of a job. Boone’s new venture would prove to be hugely successful, giving us the whiteboards now ubiquitous to seemingly every office or cubicle in the world and making Boone himself very, very rich. But even had they been able to predict his future that wouldn’t have been much consolation for Fargo and his suddenly forlorn little pair of programmers.

Fargo decided that it really shouldn’t be that hard for him to do what Michael Boone had been doing in addition to managing the development team. In fact, he had already been working on a side venture, a potential $60,000 contract with World Book Encyclopedia to make some rote educational titles of the drill-and-practice stripe. After signing that contract, he founded Interplay Productions to see it through. It wasn’t a glamorous beginning, but it represented programs that could be knocked out quickly to start bringing in money. Heineman and Worrell agreed to stay with Fargo and try to make it work. Fargo added another programmer named Jay Patel to complete this initial incarnation of Interplay. The next six to nine months consisted of Fargo hustling up whatever work he could find, game or non-game, and his team hammering it out: “We did work for the military, stuff for McGraw Hill — we did anything we could do. We didn’t have the luxury of creating our own software. We had to do other people’s work and just kept our ideas in the back of our minds.”

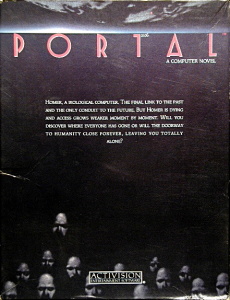

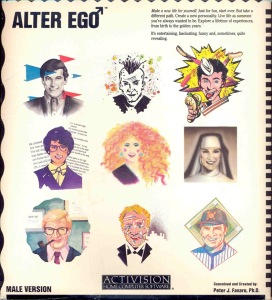

The big break they’d been hoping for came midway through 1984. Interplay “hit Activision’s radar,” and Activision decided to let Fargo and company make some adventure games for them. Activision at the time was reeling from the Great Videogame Crash, which had destroyed their immensely profitable cartridge business almost overnight. CEO Jim Levy had decided that the future of the company, if it was to have one, must lie with software for home computers. With little expertise in this area, he was happy to sign up even an unproven outside developer like the nascent Interplay. Mindshadow and The Tracer Sanction, the first two games Interplay was actually willing to put their name on, were the results.

Fargo’s team had found time to dissect Infocom games and tinker with parsers and adventure-game engines even back during their days as Boone Corporation. Mindshadow and Tracer Sanction were logical extensions of that experimentation and, going back even further, of Fargo’s first game The Demon’s Forge. Fargo found a young artist named Dave Lowery, who would go on to quite an impressive career in film, to draw the pictures for Mindshadow; they came out looking a cut above most of the competition in the crowded field of illustrated adventure games. Mindshadow‘s Bourne Identity-inspired plot has you waking up with amnesia on a deserted island. Once you escape the island, you embark on a globe-trotting quest to recover your memories. There’s an interesting metaphysical angle to a game that’s otherwise fairly typical of its period and genre. As you encounter new people, places, and things that you should know from your earlier life, you can use the verb “remember” to fit them into place and slowly rebuild your shattered identity.

Mindshadow did relatively well for Interplay and Activision, not a blockbuster but a solid seller that seemed to bode well for future collaborations. Less successful both aesthetically and commercially was Tracer Sanction, a science-fiction adventure that isn’t quite sure whether it wants to be serious or humorous and lacks a conceptual hook like Mindshadow‘s “remember” gimmick. But by the time it appeared Fargo had already shifted much of his team’s energy away from adventure games and into the CRPG project that would become The Bard’s Tale.

Fargo and his old high-school buddy Michael Cranford had been dreaming of doing a CRPG since about five minutes after they had first seen Wizardry back in 1981. Cranford had even made a stripped-down CRPG on his own, published on a Commodore 64 cartridge by Human Engineered Software under the title Maze Master in 1983 to paltry sales. Now Fargo convinced him to help his little team at Interplay create a Wizardry killer. It seemed high time for such an undertaking, what with the Wizardry series still using ugly monochrome wire frames to depict its dungeons and monsters and available only on the Apple II, Macintosh, and IBM PC — a list which notably didn’t include the biggest platform in the industry, the Commodore 64. Indeed, CRPGs of any sort were quite thin on the ground for the Commodore 64, decent ones even more so. Fargo:

At the time, the gold standard was Wizardry for that type of game. There was Ultima, but that was a different experience, a top-down view, and not really as party-based. Sir-Tech was kind of saying, “Who needs color? Who needs music? Who needs sound effects?” But my attitude was, “We want to find a way to use all those things. What better than to have a main character who uses music as part of who he is?”

Soon the game was far enough along for Fargo to start shopping it to publishers. His first stop was naturally Activision. One of Jim Levy’s major blind spots, however, was the whole CRPG genre. He simply couldn’t understand the appeal of killing monsters, mapping dungeons, and building characters, reportedly pronouncing Interplay’s project “nicheware for nerds.” And so Fargo ended up across town at Electronic Arts, who, recognizing that Trip Hawkins’s original conception of “simple, hot, and deep” wasn’t quite the be-all end-all in a world where all entertainment software was effectively “nicheware for nerds,” were eager to diversify into more hardcore genres like the CRPG. EA’s marketing director Bing Gordon zeroed in on the appeal of one of Cranford’s relatively few expansions on Wizardry, the character of the bard. He went so far as to change the game’s name from Shadow Snare to The Bard’s Tale to highlight him, creating a lovable rogue to serve as the star of advertisements and box copy who barely exists in the game proper: “When the going gets tough, the bard goes drinking.” Beyond that, promoting The Bard’s Tale was just a matter of trumpeting the game’s audiovisual appeal in contrast to the likes of Wizardry. Released in plenty of time for Christmas 1985, with all of EA’s considerable promotional savvy and financial muscle behind it, The Bard’s Tale shocked even its creators and its publisher by outselling the long-awaited Ultima IV that appeared just a few weeks later. Interplay had come into the big time; Fargo’s days of scrabbling after any work he could find looked to be over for a long, long time to come. In the end, The Bard’s Tale would sell more than 400,000 copies, becoming the best-selling single CRPG of the 1980s.

The inevitable Bard’s Tale sequel was completed and shipped barely a year later. Another solid hit at the time on the strength of its burgeoning franchise’s name, it’s generally less fondly remembered today by fans. It seems that Michael Cranford and Fargo had had a last-minute falling-out over royalties just as the first Bard’s Tale was being completed, which led to Cranford literally holding the final version of the game for ransom until a new agreement was reached. A new deal was brokered in the nick of time, but the relationship between Cranford and Interplay was irretrievably soured. Cranford was allowed to make The Bard’s Tale II: The Destiny Knight, but he did so almost entirely on his own, using much of the tools and code he and Interplay’s core team had developed together for the first game. The lack of oversight and testing led to a game that was insanely punishing even by the standards of the era, one that often felt sadistic just for the sake of it. Afterward Cranford parted company with Interplay forever to study theology and philosophy at university.

Despite having rejected The Bard’s Tale themselves, Activision was less than thrilled with Interplay’s decision to publish the games through EA, especially after they turned into exactly the sorts of raging hits that they desperately needed for themselves. Fargo notes that Activision and EA “just hated each other,” far more so even than was the norm in an increasingly competitive industry. Perhaps they were just too much alike. Jim Levy and Trip Hawkins both liked to think of themselves as hip, with-it guys selling the future of art and entertainment to equally hip, with-it buyers. Both were fond of terms like “software artist,” and both drew much of their marketing and management approaches from the world of rock and roll. Little Interplay had a tough task tiptoeing between these two bellicose elephants. Fargo:

We were maybe the only developer doing work for both companies at the same time, and they just grilled me whenever they had the chance. Whenever there was any kind of leak, they’d say, “Did you say anything?” I was right in the middle there. I always made sure to keep my mouth shut about everything.

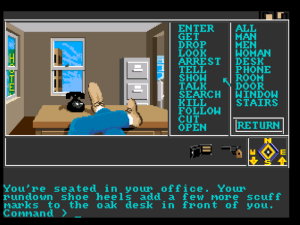

Still, Fargo managed for a while to continue doing adventure games for Activision alongside CRPGs for EA. Interplay’s Activision adventure for 1985, Borrowed Time, might just be their best. It was created at that interesting moment when developers were beginning to realize that traditional parser-based adventure games, even of the illustrated variety, might not cut it commercially much longer, but when they weren’t yet quite sure how to evolve the genre to make it more accessible and not seem like a hopeless anachronism on slick new machines like the Atari ST and Amiga. Borrowed Time is built on the same engine that had already powered Mindshadow and The Tracer Sanction, but it sports an attempt at providing an alternative to the keyboard via a list of verbs and nouns and a clickable graphic inventory. It’s all pretty half-baked, however, in that the list of nouns are suitable to the office where you start the game but bizarrely never change thereafter, while there are no hotspots on the pictures proper. Nor does the verb list contain all the verbs you actually need to finish the game. Thus even the most enthusiastic point-and-clicker can only expect to switch back and forth constantly between mouse or joystick and keyboard, a process that strikes me as much more annoying than just typing everything.

Thankfully, the game has been thought through more than its interface. Realizing that neither he nor anyone else amongst the standard Interplay crew were all that good at writing prose, Fargo contacted Bill Kunkel, otherwise known as “The Game Doctor,” who had made a name for himself as a sort of Hunter S. Thompson of videogame journalism via his column in Electronic Games magazine. Fargo’s pitch was simple: “Okay, you guys have a lot of opinions about games, how would you like to do one?” Kunkel, along with some old friends and colleagues named Arnie Katz and Joyce Worley, decided that they would like that very much, forming a little company called Subway Software to represent their partnership. Subway proceeded to write all of the text and do much of the design for Borrowed Time. Fargo gave them a “Script by” credit for their contributions, the first of many such design credits Subway would receive over the years to come (a list that includes Star Trek: First Contact for Simon & Schuster).

Like Déjà Vu, ICOM Simulations’s breakthrough point-and-click graphic adventure of the same year, Borrowed Time plays in the hard-boiled 1930s milieu of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. The tones and styles of the two games are very similar. Both love to make sardonic fun of the hapless, down-on-his-luck PI who serves as protagonist almost as much as they love to kill him, and both mix opportunities for free exploration with breakneck chases and other linear bits of derring-do in service of some unusually complicated plots. And I like both games on the whole, despite some unforgiving old-school design decisions. While necessarily minimalist given the limitations of Interplay’s engine, the text of Borrowed Time in particular is pretty good at evoking its era and genre inspirations.

Collaborations like the one that led to Borrowed Time highlight one of the most interesting aspects of Fargo’s approach to game development. In progress as well in many other companies by the mid-1980s, it represented a quiet revolution in the way games got made that was changing the industry.

With Interplay, I wanted to take [development] beyond one- or two-man teams. That sounds like an obvious idea now, but to hire an artist to do the art, a musician to do the music, a writer to do the writing, all opposed to just the one-man show doing everything, was novel. Even with Demon’s Forge, I had my buddy Michael do all the art, but I had to trace it all and put it in the computer, and that lost a certain something. And because I didn’t know a musician or a sound guy, it had no music or sound. I did the writing, but I don’t think that’s my strong point. So, really, [Interplay was] set up to say, “Let’s take a team approach and bring in specialists.”

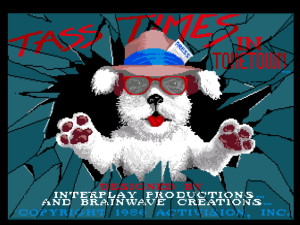

One of the specialists Fargo brought in for Interplay’s fourth and final adventure game for Activision, 1986’s Tass Times in Tonetown, we already know very well.

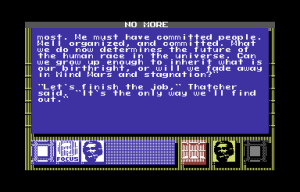

After leaving Infocom in early 1985, just in time to avoid the chaos and pain brought on by Cornerstone’s failure, Mike Berlyn along with his wife Muffy had hung out their shingle as Brainwave Creations. The idea was to work as consultants, doing game design only rather than implementation — yet another sign of the rapidly encroaching era of the specialist. Brainwave entered talks with several companies, including Brøderbund, Origin, and even Infocom. However, with the industry in general and the adventure game in particular in a state of uncertain flux, it wasn’t until Interplay came calling that anything came to fruition. Brian Fargo gave Mike and Muffy carte blanche to do whatever they wanted, as long as it was an adventure game. What they came up with was a bizarre day-glo riff on New Wave music culture, with some of the looks and sensibilities of The Jetsons. The adjective “tass,” the game’s universal designation for anything cool, fun, good, or desirable, hails from the Latin “veritas” — truth. The Berlyns took to pronouncing it as “very tass,” and soon “tass” was born. In the extra-dimensional city of Tonetown guitar picks stand in for money, a talking dog is a star reporter, and a “combination of pig, raccoon, and crocodile” named Franklin Snarl is trying to buy up all of the land, build tract houses, and transform the place into a boring echo of Middle American suburbia. Oh, and he’s also kidnapped your dimension-hopping grandfather. That’s where you come in.

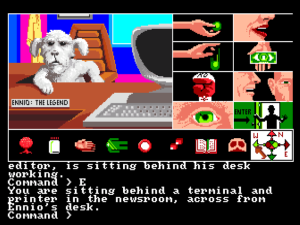

I’ve heard Tass Times in Tonetown described from time to time as a “cult classic,” and who am I to argue? It’s certainly appealing at first blush, when you peruse the charmingly cracked Tonetown Times newspaper included in its package. The newspaper gives ample space to Ennio, the aforementioned dog reporter who owes more than a little something to the similarly anthropomorphic and similarly cute dogs of Berlyn’s last game for Infocom, the computerized board game Fooblitzky. It seems old Ennio — whom Berlyn named after film composer Ennio Morricone of spaghetti western fame — has been investigating the mundane dimension from which you hail under deep cover as your gramps’s dog Spot. Interplay’s adventure engine, while still clearly derivative of the earlier games, has been vastly improved, with icons now taking the place of lists of words and the graphics themselves filled — finally — with clickable hotspots. The bright, cartoon-surrealistic graphics still look great today, particularly in the Amiga version.

Settle in to really, seriously play, though, and problems quickly start to surface. It’s hard to believe that this game was co-authored by someone who had matriculated for almost three years at Infocom because it’s absolutely riddled with exactly the sort of frustrations that Infocom relentlessly purged from their own games. To play Tass Times in Tonetown is to die over and over and over again, usually with no warning. Walk through gramps’s dimensional gate and start to explore — bam, you’re dead because you haven’t outfitted yourself in the proper bizarre Tonetown attire. Ring the bell at an innocent-looking gate — bam, you’re dead because this gate turns out to be the front gate of the villain’s mansion. Descend a well and go west — bam, a monster kills you. Try to explore the swamp outside of town — bam, another monster kills you. The puzzles all require fairly simple actions to solve, but exactly which actions they are can only be divined through trial and error. Coupled with the absurd lethality of the game, that leads to a numbing cycle of saving, trying something, dying, and then repeating again and again until you stumble on the right move. The length of this very short game is also artificially extended via a harsh inventory limit and one or two nasty opportunities to miss your one and only chance to do something vital, which can leave you a dead adventurer walking through most of the game. As is depressingly typical of Mike Berlyn, the writing is clear and grammatically correct but a bit perfunctory, with most of the real wit offloaded to the graphics and the accompanying newspaper. And even the slick interface isn’t quite all that it first seems to be. The “Hit” icon is of absolutely no use anywhere in the game. Even more strange is the “Tell Me About” icon, which is not only useless but not even understood by the parser. Meanwhile other vital verbs still go unrepresented graphically; thus you still don’t totally escape the tyranny of the keyboard. Borrowed Time isn’t as pretty or as strikingly original as Tass Times in Tonetown, and it’s only slightly more shy about killing you, but on the whole it’s a better game, the one that gets my vote for the first one to play for those curious about Interplay’s take on the illustrated text adventure.

Thanks to the magic of pre-release hardware, Interplay got their adventures with shocking speed onto the next generation of home computers represented by the Atari ST, the Amiga, and eventually the Apple IIGS. Well before Tass Times in Tonetown, new versions of Mindshadow and Borrowed Time, updated with new graphics and, in the case of the former, the somewhat ineffectual point-and-click word lists of the latter, became two of the first three games a proud new Amiga owner could actually buy. Similarly, the IIGS version of Tass Times in Tonetown was released on the same day in September of 1986 as the IIGS itself. While the graphics weren’t quite up to the Amiga version’s standard, the game’s musical theme sounded even better played through the IIGS’s magnificent 16-voice Ensoniq synthesizer chip. Equally well-done ports of The Bard’s Tale games to all of these platforms would soon follow, part and parcel of one of Fargo’s core philosophies: “Whenever we do an adaptation of a product to a different machine, we always take full advantage of all of the machine’s new features. There’s nothing worse than looking at graphics that look like [8-bit] Apple graphics on a more sophisticated machine.”

And, lo and behold, Interplay finally finished their IBM PC-based recreation of Pebble Beach in 1986, last legacy of their days as Boone Corporation. It was published by Activision’s Gamestar sports imprint under the ridiculously long-winded title of Championship Golf: The Great Courses of the World — Volume One: Pebble Beach. It was soon ported to the Amiga, but sales in a suddenly very crowded golf-simulation field weren’t enough to justify a Volume Two. Despite their sporty founder, Interplay would leave the sports games to others henceforth. They would also abandon the adventure games that were by now becoming a case of slowly diminishing returns to focus on building on the CRPG credibility they enjoyed in spades thanks to The Bard’s Tale.

Interplay as of 1987. Even then, four years after the company’s founding, all of the employees were still well shy of thirty.

By 1987, then, Brian Fargo had established his company as a proven industry player. Over many years still to come with Fargo at the helm, Interplay would amass a track record of hits and cult touchstones that can be equaled by no more than a handful of others in gaming’s history. They would largely deliver games rooted in the traditional fantasy and science-fiction tropes that gamers can never seem to get enough of, executed using mostly proven, traditional mechanics. But as often as not they then would garnish this comfort food with just enough innovation, just enough creative spice to keep things fresh, to keep them feeling a cut above their peers. The Bard’s Tale would become something of a template: execute the established Wizardry formula very well, add lots of colorful graphics and sound, and innovate modestly, but not enough to threaten delicate sensibilities. Result: blockbuster. The balance between commercial appeal and innovation is a delicate one in any creative field, games perhaps more than most. For many years few were better at walking that tightrope than Interplay, making them a necessary perennial in any history of games as a commercial or an artistic proposition. The fact that this blog strives to be both just means they’re likely to show up all that much more in the years to come.

(Sources: The book Stay Awhile and Listen by David L. Craddock; Commodore Magazine of December 1987; Softline of January 1982, March 1982, May 1982, September 1982, January 1983, September/October 1983, and November/December 1983; Amazing Computing of April 1986; Compute!’s Gazette of September 1983; Microtimes of March 1987; Orange Coast of July 2000, August 2000, September 2000, and May 2001; Questbusters of March 1991. Online sources include: Matt Barton’s interview with Rebecca Heineman, parts 1 and 3; Barton’s interview with Brian Fargo, part 1; Digital Press’s interview with Heineman; Gamestar’s interview with Fargo; interviews with Bill Kunkel at Gamasutra, Good Deal Games, and 8-bit Rocket; “trivia” in the MobyGames page on Tass Times in Tonetown; and a VentureBeat article on Interplay. Also Jason Scott’s interview with Mike Berlyn for Get Lamp that he was kind enough to share with me. And thanks to Alex Smith for sharing the “nicheware for nerds” anecdote about Jim Levy in a comment on this blog. Feel free to download the Amiga versions of Borrowed Time and Tass Times in Tonetown from right here if you like.

I’ve finally rolled out a new minimalist version of this site for phone browsers. If you notice that anything seems to have gone sideways somewhere with it, let me know.

The Digital Antiquarian will be taking a holiday next week. Dorte and I are heading to Rome for a little getaway. But it’ll be back to business the week after, when we’ll cross the pond again at last to look at some developments in Britain and Europe.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Bill Heineman now lives as Rebecca Heineman. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. |

|---|