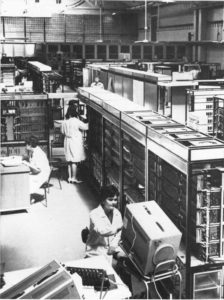

Seen from certain perspectives, Soviet computer hardware as an innovative force of its own peaked as early as 1968, the year the first BESM-6 computer was powered up. The ultimate evolution of the line of machines that had begun with Sergei Lebedev’s original MESM, the BESM-6 was the result of a self-conscious attempt on the part of Lebedev’s team at ITMVT to create a world-class supercomputer. By many measures, they succeeded. Despite still being based on transistors rather than the integrated circuits that were becoming more and more common in the West, the BESM-6’s performance was superior to all but the most powerful of its Western peers. The computers generally acknowledged as the fastest in the world at the time, a line of colossi built by Control Data in the United States, were just a little over twice as fast as the BESM-6, which had nothing whatsoever to fear from the likes of the average IBM mainframe. And in comparison to other Soviet computers, the BESM-6 was truly a monster, ten times as fast as anything the country had managed to produce before. In its way, the BESM-6 was as amazing an achievement on Lebedev’s part as had been the MESM almost two decades earlier. Using all home-grown technology, Lebedev and his people had created a computer almost any Western computer lab would have been proud to install.

At the same time, though, the Soviet computer industry’s greatest achievement to date was, almost paradoxically, symbolic of all its limitations. Sparing no expense nor effort to build the best computer they possibly could, Lebedev’s team had come close to but not exceeded the Western state of the art, which in the meantime continued marching inexorably forward. All the usual inefficiencies of the Soviet economy conspired to prevent the BESM-6 from becoming a true game changer rather than a showpiece. BESM-6s would trickle only slowly out of the factories; only about 350 of them would be built over the course of the next 20 years. They became useful tools for the most well-heeled laboratories and military bases, but there simply weren’t enough of them to implement even a fraction of the cybernetics dream.

A census taken in January of 1970 held that there were just 5500 computers operational in the Soviet Union, as compared with 62,500 in the United States and 24,000 in Western Europe. Even if one granted that the BESM-6 had taken strides toward solving the problem of quality, the problem of quantity had yet to be addressed. Advanced though the BESM-6 was in so many ways, for Soviet computing in general the same old story held sway. A Rand Corporation study from 1970 noted that “the Soviets are known to have designed micro-miniaturized circuits far more advanced than any observed in Soviet computers.” The Soviet theory of computing, in other words, continued to far outstrip the country’s ability to make practical use of it. “In the fundamental design of hardware and software the Russian computer art is as clever as that to be found anywhere in the world,” said an in-depth Scientific American report on the state of Soviet computing from the same year. “It is in the quality of production, not design, that the USSR is lagging.”

One way to build more computers more quickly, the Moscow bureaucrats concluded, was to share the burden among their partners (more accurately known to the rest of the world as their vassal states) in the Warsaw Pact. Several member states — notably East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary — had fairly advanced electronics industries whose capabilities in many areas exceeded that of the Soviets’ own, not least because their geographical locations left them relatively less isolated from the West. At the first conference of the International Center of Scientific and Technical Information in January of 1970, following at least two years of planning and negotiating, the Soviet Union signed an agreement with East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, and Romania to make the first full-fledged third-generation computer — one based on integrated circuits rather than transistors — to come out of Eastern Europe. The idea of dividing the labor of producing the new computer was taken very literally. In a testimony to the “from each according to his means” tenet of communism, Poland would make certain ancillary processors, tape readers, and printers; East Germany would make other peripherals; Hungary would make magnetic memories and some systems software; Czechoslovakia would make many of the integrated circuits; Romania and Bulgaria, the weakest sisters in terms of electronics, would make various mechanical and structural odds and ends; and the Soviet Union would design the machines, make the central processors, and be the final authority on the whole project, which was dubbed “Ryad,” a word meaning “row” or “series.”

The name was no accident. On the contrary, it was key to the nature of the computer — or, rather, computers — the Soviet Union and its partners were now planning to build. With the BESM-6 having demonstrated that purely home-grown technology could get their countries close to the Western state of the art but not beyond it, they would give up on trying to outdo the West. Instead they would take the West’s best, most proven designs and clone them, hoping to take advantage of the eye toward mass production that had been baked into them from the start. If all went well, 35,000 Ryad computers would be operational across the Warsaw Pact by 1980.

In a sense, the West had made it all too easy for them, given Project Ryad all too tempting a target for cloning. In 1964, in one of the most important developments in the history of computers, IBM had introduced a new line of mainframes called the System/360. The effect it had on the mainframe industry of the time was very similar to the one which the IBM PC would have on the young microcomputer industry 17 years later: it brought order and stability to what had been a confusion of incompatible machines. For the first time with the System/360, IBM created not just a single machine or even line of machines but an entire computing ecosystem built around hardware and software compatibility across a wide swathe of models. The effect this had on computing in the West is difficult to overstate. There was, for one thing, soon a large enough installed base of System/360 machines that companies could make a business out of developing software and selling it to others; this marked the start of the software industry as we’ve come to know it today. Indeed, our modern notion of computing platforms really begins with the System/360. Dag Spicer of the Computer History Museum calls it IBM’s Manhattan Project. Even at the time, IBM’s CEO Thomas Watson Jr. called it the most important product in his company’s already storied history, a distinction which is challenged today only by the IBM PC.

The System/360 ironically presaged the IBM PC in another respect: as a modular platform built around well-documented standards, it was practically crying out to be cloned by companies that might have trailed IBM in terms of blue-sky technical innovation, but who were more than capable of copying IBM’s existing technology and selling it at a cheaper price. Companies like Amdahl — probably the nearest equivalent to IBM’s later arch-antagonist Compaq in this case of parallel narratives — lived very well on mainframes compatible with those of IBM, machines which were often almost as good as IBM’s best but were always cheaper. None too pleased about this, IBM responded with various sometimes shady countermeasures which landed them in many years of court cases over alleged antitrust violations. (Yes, the histories of mainframe computing and PC computing really do run on weirdly similar tracks.)

If the System/360 from the standpoint of would-be Western cloners was an unlocked door waiting to be opened, from the standpoint of the Soviet Union, which had no rules for intellectual property whatsoever which applied to the West, the door was already flung wide. Thus, instead of continuing down the difficult road of designing its high-end computers from scratch, the Soviet Union decided to stroll on through.

There’s much that could be said about what this decision symbolized for Soviet computing and, indeed, for Soviet society in general. For all the continuing economic frustrations lurking below the surface of the latest Pravda headlines, Khrushchev’s rule had been the high-water mark of Soviet achievement, when the likes of the Sputnik satellite and Yuri Gagarin’s flight into space had seemed to prove that communism really could go toe-to-toe with capitalism. But the failure to get to the Moon before the United States among other disappointments had taken much of the shine off that happy thought. [1]Some in the Soviet space program actually laid their failure to get to the Moon, perhaps a bit too conveniently, directly at the feet of the computer technology they were provided, noting that the lack of computers on the ground equal to those employed by NASA — which happened to be System/360s — had been a crippling disadvantage. Meanwhile the computers that went into space with the Soviets were bigger, heavier, and less capable than their American counterparts. In the rule of Leonid Brezhnev, which began with Khrushchev’s unceremonious toppling from power in October of 1964, the Soviet Union gradually descended into a lazy decrepitude that gave only the merest lip service to the old spirit of revolutionary communism. Corruption had always been a problem, but now, taking its cue from its new leader, the country became a blatant oligarchy. While Brezhnev and his cronies collected dachas and cars, their countryfolk at times literally starved. Perhaps the greatest indictment of the system Brezhnev perpetuated was the fact that by the 1970s the Soviet Union, in possession of more arable land than any nation on earth and with one of the sparsest populations of any nation in relation to its land mass, somehow still couldn’t feed itself, being forced to import millions upon millions of tons of wheat and other basic foodstuffs every year. Thus Brezhnev found himself in the painful position, all too familiar to totalitarian leaders, of being in some ways dependent on the good graces of the very nations he denigrated.

In the Soviet Union of Leonid Brezhnev, bold ideas like the dream of cybernetic communism fell decidedly out of fashion in favor of nursing along the status quo. Every five years, the Party Congress reauthorized ongoing research into what had become known as the “Statewide Automated Management System for Collection and Processing of Information for the Accounting, Planning, and Management of the National Economy” (whew!), but virtually nothing got done. The bureaucratic infighting that had always negated the perceived advantages of communism — as perceived optimistically by the Soviets, and with great fear by the West — was more pervasive than ever in these late years. “The Ministry of Metallurgy decides what to produce, and the Ministry of Supplies decides how to distribute it. Neither will yield its power to anyone,” said one official. Another official described each of the ministries as being like a separate government unto itself. Thus there might not be enough steel to make the tractors the country’s farmers needed to feed its people one year; the next, the steel might pile up to rust on railway sidings while the erstwhile tractor factories were busy making something else.

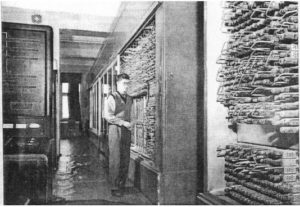

Amidst all the infighting, Project Ryad crept forward, behind schedule but doggedly determined. This new face of computing behind the Iron Curtain made its public bow at last in May of 1973, when six of the seven planned Ryad “Unified System” models were in attendance at the Exposition of Achievements of the National Economy in Moscow. All were largely hardware- and software-compatible with the IBM System/360 line. Even the operating systems that were run on the new machines were lightly modified copies of Western operating systems like IBM’s DOS/360. Project Ryad and its culture of copying would come to dominate Soviet computing during the remainder of the 1970s. A Rand Corporation intelligence report from 1978 noted that “by now almost everything offered by IBM to 360 installations has been acquired” by the Soviet Union.

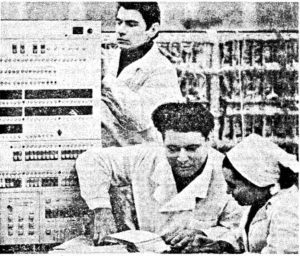

Project Ryad even copied the white lab coats worn by the IBM “priesthood” (and gleefully scorned by the scruffier hackers who worked on the smaller but often more innovative machines produced by companies like DEC).

During the five years after the Ryad machines first appeared, IBM sold about 35,000 System/360 machines, while the Soviet Union and its partners managed to produce about 5000 Ryad machines. Still, compared to what the situation had been before, 5000 reasonably modern machines was real progress, even if the ongoing inefficiencies of the Eastern Bloc economies kept Project Ryad from ever reaching more than a third of its stated yearly production goals. (A telling sign of the ongoing disparities between West and East was the way that all Western estimates of future computer production tended to vastly underestimate the reality that actually arrived, while Eastern estimates did just the opposite.) If it didn’t exactly allow Eastern Europe to make strides toward any bold cybernetic future — on the contrary, the Warsaw Pact economies continued to limp along in as desultory a fashion as ever — Project Ryad did do much to keep its creator nations from sliding still further into economic dysfunction. Unsurprisingly, a Ryad-2 generation of computers was soon in the works, cloning the System/370, IBM’s anointed successor to the System/360 line. Other projects cloned the DEC PDP line of machines, smaller so-called “minicomputers” suitable for more modest — but, at least in the West, often more interesting and creative — tasks than the hulking mainframes of IBM. Soviet watcher Seymour Goodman summed up the current situation in an article for the journal World Politics in 1979:

The USSR has learned that the development of its national computing capabilities on the scale it desires cannot be achieved without a substantial involvement with the rest of the world’s computing community. Its considerable progress over the last decade has been characterized by a massive transfer of foreign computer technology. The Soviet computing industry is now much less isolated than it was during the 1960s, although its interfaces with the outside world are still narrowly defined. It would appear that the Soviets are reasonably content with the present “closer but still at a distance” relationship.

Reasonable contentment with the status quo would continue to be the Kremlin’s modus operandi in computing, as in most other things. The fiery rhetoric of the past had little relevance to the morally and economically bankrupt Soviet state of the 1970s and 1980s.

Even in this gray-toned atmosphere, however, the old Russian intellectual tradition remained. Many of the people designing and programming the nation’s computers barely paid attention to the constant bureaucratic turf wars. They’d never thought that much about philosophical abstractions like cybernetics, which had always been more a brainchild of the central planners and social theorists than the people making the Soviet Union’s extant computer infrastructure, such as it was, work. Like their counterparts in the West, Soviet hackers were more excited by a clever software algorithm or a neat hardware re-purposing than they were by high-flown social theory. Protected by the fact that the state so desperately needed their skills, they felt free at times to display an open contempt for the supposedly inviolate underpinnings of the Soviet Union. Pressed by his university’s dean to devote more time to the ideological studies that were required of every student, one young hacker said bluntly that “in the modern world, with its super-speedy tempo of life, time is too short to study even more necessary things” than Marxism.

Thus in the realm of pure computing theory, where advancement could still be made without the aid of cutting-edge technology, the Soviet Union occasionally made news on the world stage with work evincing all the originality that Project Ryad and its ilk so conspicuously lacked. In October of 1978, a quiet young researcher at the Moscow Computer Center of the Soviet Academy of Sciences named Leonid Genrikhovich Khachiyan submitted a paper to his superiors with the uninspiring — to non-mathematicians, anyway — title of “Polynomial Algorithms in Linear Programming.” Following its publication in the Soviet journal Reports of the Academy of Sciences, the paper spread like wildfire across the international community of mathematics and computer science, even garnering a write-up in the New York Times in November of 1979. (Such reports were always written in a certain tone of near-disbelief, of amazement that real thinking was going on in the Mirror World.) What Khachiyan’s paper actually said was almost impossible to clearly explain to people not steeped in theoretical mathematics, but the New York Times did state that it had the potential to “dramatically ease the solution of problems involving many variables that up to now have required impossibly large numbers of separate computer calculations,” with potential applications in fields as diverse as economic planning and code-breaking. In other words, Khachiyan’s new algorithms, which have indeed stood the test of time in many and diverse fields of practical application, can be seen as a direct response to the very lack of computing power with which Soviet researchers constantly had to contend. Sometimes less really could be more.

As Khachiyan’s discoveries were spreading across the world, the computer industries of the West were moving into their most world-shaking phase yet. A fourth generation of computers, defined by the placing of the “brain” of the machine, or central processing unit, all on a single chip, had arrived. Combined with a similar miniaturization of the other components that went into a computer, this advancement meant that people were able for the first time to buy these so-called “microcomputers” to use in their homes — to write letters, to write programs, to play games. Likewise, businesses could now think about placing a computer on every single desk. Still relatively unremarked by devotees of big-iron institutional computing as the 1970s expired, over the course of the 1980s and beyond the PC revolution would transform the face of business and entertainment, empowering millions of people in ways that had heretofore been unimaginable. How was the Soviet Union to respond to this?

Alexi Alexandrov, the president of the Moscow Academy of Sciences, responded with a rhetorical question: “Have [the Americans] forgotten that problems of no less complexity, such as the creation of the atomic bomb or space-rocket technology… [we] were able to solve ourselves without any help from abroad, and in a short time?” Even leaving aside the fact that the Soviet atomic bomb was itself built largely using stolen Western secrets, such words sounded like they heralded a new emphasis on original computer engineering, a return to the headier days of Khrushchev. In reality, though, the old ways were difficult to shake loose. The first Soviet microprocessor, the KP580BM80A of 1977, had its “inspiration” couched inside its very name: the Intel 8080, which was along with the Motorola 6800 one of the two chips that had launched the PC revolution in the West in 1974.

Yet in the era of the microchip the Soviet Union ran into problems continuing the old practices. While technical schematics for chips much newer and more advanced than the Intel 8080 were soon readily enough available, they were of limited use in Soviet factories, which lacked the equipment to stamp out the ever more miniaturized microchip designs coming out of Western companies like Intel.

One solution might be for the Soviets to hold their noses and outright buy the chip-fabricating equipment they needed from the West. In earlier decades, such deals had hardly been unknown, although they tended to be kept quiet by both parties for reasons of pride (on the Eastern side) and public relations (on the Western side). But, unfortunately for the Soviets, the West had finally woken up to the reality that microelectronics were as critical to a modern war machine as missiles and fighter planes. A popular story that circulated around Western intelligence circles for years involved Viktor Belenko, a Soviet pilot who went rogue, flying his state-of-the-art MiG-25 fighter jet to a Japanese airport and defecting there in 1976. When American engineers examined his MiG-25, they found a plane that was indeed a technological marvel in many respects, able to fly faster and higher than any Western fighter. Yet its electronics used unreliable vacuum tubes rather than transistors, much less integrated circuits — a crippling disadvantage on the field of battle. The contrast with the West, which had left the era of the vacuum tube behind almost two decades ago, was so extreme that there was some discussion of whether Belenko might be a double agent, his whole defection a Soviet plot to convince the West that they were absurdly far behind in terms of electronics technology. Sadly for the Soviets, the vacuum tubes weren’t the result of any elaborate KGB plot, but rather just a backward electronics industry.

In 1979, the Carter Administration began to take a harder line against the Soviet Union, pushing through Congress as part of the Export Administration Act a long list of restrictions on what sorts of even apparently non-military computer technology could legally be sold to the Eastern Bloc. Ronald Reagan then enforced and extended these restrictions upon becoming president in 1981, working with the rest of the West in what was known as the Coordination Committee on Export Controls, or COCOM — a body that included all of the NATO member nations, plus Japan and Australia — to present a unified front. By this point, with the Cold War heading into its last series of dangerous crises thanks to Reagan’s bellicosity and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the United States in particular was developing a real paranoia about the Soviet Union’s long-standing habits of industrial espionage. The paranoia was reflected in CIA director William Casey’s testimony to Congress in 1982:

The KGB has developed a large, independent, specialized organization which does nothing but work on getting access to Western science and technology. They have been recruiting about 100 young scientists and engineers a year for the last 15 years. They roam the world looking for technology to pick up. Back in Moscow, there are 400 to 500 assessing what they might need and where they might get it — doing their targeting and then assessing what they get. It’s a very sophisticated and far-flung organization.

By the mid-1980s, restrictions on Western computer exports to the East were quite draconian, a sometimes bewildering maze of regulations to be navigated: 8-bit microcomputers could be exported but 16-bit microcomputers couldn’t be; a single-user accounting package could be exported but not a multi-user version; a monochrome monitor could be exported but not a color monitor.

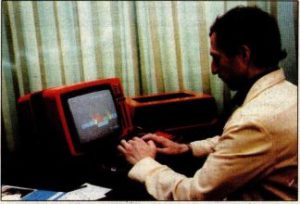

Even as the barriers between East and West were being piled higher than ever, Western fascination with the Mirror World remained stronger than ever. In August of 1983, an American eye surgeon named Leo D. Bores, organizer of the first joint American/Soviet seminar in medicine in Moscow and a computer hobbyist in his spare time, had an opportunity to spend a week with what was billed as the first ever general-purpose Soviet microcomputer. It was called the “Agat” — just a pretty name, being Russian for the mineral agate — and it was largely a copy — in Bores’s words a bad copy — of the Apple II. His report, appearing belatedly in the November 1984 issue of Byte magazine, proved unexpectedly popular among the magazine’s readership.

The Agat was, first of all, much, much bigger and heavier than a real Apple II; Bores generously referred to it as “robust.” It was made in a factory more accustomed to making cars and trucks, and, indeed, it looked much as one might imagine a computer built in an automotive plant would look. The Soviets had provided software for displaying text in Cyrillic, albeit with some amount of flicker, using the Apple II’s bitmap-graphics modes. The keyboard also offered Cyrillic input, thus solving, after a fashion anyway, a big problem in adapting Western technology to Soviet needs. But that was about the extent to which the Agat impressed. “The debounce circuitry [on the keyboard] is shaky,” noted Bores, “and occasionally a stray character shows up, especially during rapid data entry. The elevation of the keyboard base (about 3.5 centimeters) and the slightly steeper-than-normal board angle would cause rapid fatigue as well as wrist pain after prolonged use.” Inside the case was a “nightmarish wiring maze.” Rather than being built into a single motherboard, the computer’s components were all mounted on separate breadboards cobbled together by all that cabling, the way Western engineers worked only in the very early prototyping stage of hardware development. The Soviet clone of the MOS 6502 chip found at the heart of the Agat was as clumsily put together as the rest of the machine, spanning across several breadboards; thus this “first Soviet microcomputer” arguably wasn’t really a microcomputer at all by the strict definition of the term. The kicker was the price: about $17,000. As that price would imply, the Agat wasn’t available to private citizens at all, being reserved for use in universities and other centers of higher learning.

With the Cold War still going strong, Byte‘s largely American readership was all too happy to jeer at this example of Soviet backwardness, which certainly did show a computer industry lagging years behind the West. That said, the situation wasn’t quite as bad as Bores’s experience would imply. It’s very likely that the machine he used was a pre-production model of the Agat, and that many of the problems he encountered were ironed out in the final incarnation.

For all the engineering challenges, the most important factor impeding truly personal computing in the Soviet Union was more ideological than technical. As so many of the visionaries who had built the first PCs in the West had so well recognized, these were tools of personal empowerment, of personal freedom, the most exciting manifestation yet of Norbert Wiener’s original vision of cybernetics as a tool for the betterment of the human individual. For an Eastern Bloc still tossing and turning restlessly under the blanket of collectivism, this was anathema. Poland’s propaganda ministry made it clear that they at least feared the existence of microcomputers far more than they did their absence: “The tendency in the mass-proliferation of computers is creating a variety of ideological endangerments. Some programmers, under the inspiration of Western centers of ideological subversion, are creating programs that help to form anti-communistic political consciousness.” In countries like Poland and the Soviet Union, information freely exchanged could be a more potent weapon than any bomb or gun. For this reason, photocopiers had been guarded with the same care as military hardware for decades, and even owning a typewriter required a special permit in many Warsaw Pact countries. These restrictions had led to the long tradition of underground defiance known euphemistically simply as “samizdat,” or self-publishing: the passing of “subversive” ideas from hand to hand as one-off typewritten or hand-written texts. Imagine what a home computer with a word processor and a printer could mean for samizdat. The government of Romania was so terrified by the potential of the computer for spreading freedom that it banned the very word for a time. Harry R. Meyer, an American Soviet watcher with links to the Russian expatriate community, made these observations as to the source of such terror:

I can imagine very few things more destructive of government control of information flow than having a million stations equivalent to our Commodore 64 randomly distributed to private citizens, with perhaps a thousand in activist hands. Even a lowly Commodore 1541 disk drive can duplicate a 160-kilocharacter disk in four or five minutes. The liberating effect of not having to individually enter every character every time information is to be shared should dramatically increase the flow of information.

Information distributed in our society is mainly on paper rather than magnetic media for reasons of cost-effectiveness: the message gets to more people per dollar. The bottleneck of samizdat is not money, but time. If computers were available at any cost, it would be more effective to invest the hours now being spent in repetitive typing into earning cash to get a computer, no matter how long it took.

If I were circulating information the government didn’t like in the Soviet Bloc, I would have little interest in a modem — too easily monitored. But there is a brisk underground trade in audio cassettes of Western music. Can you imagine the headaches (literal and figurative) for security agents if text files were transported by overwriting binary onto one channel in the middle of a stereo cassette of heavy-metal music? One would hope it would be less risk to carry such a cassette than a disk, let alone a compromising manuscript.

If we accept Meyer’s arguments, there’s an ironic follow-on argument to be made: that, in working so hard to keep the latest versions of these instruments of freedom out of the hands of the Soviet Union and its vassal states, the COCOM was actually hurting rather than helping the cause of freedom. As many a would-be autocrat has learned to his dismay in the years since, it’s all but impossible to control the free flow of information in a society with widespread access to personal-computing technology. The new dream of personal computing, of millions of empowered individuals making things and communicating, stood in marked contrast to the Soviet cyberneticists’ old dream of perfect, orderly, top-down control implemented via big mainframe computers. For the hard-line communists, the dream of personal computing sounded more like a nightmare. The Soviet Union faced a stark dilemma: embrace the onrushing computer age despite the loss of control it must imply, or accept that it must continue to fall further and further behind the West. A totalitarian state like the Soviet Union couldn’t survive alongside the free exchange of ideas, while a modern economy couldn’t survive without the free exchange of ideas.

Thankfully for everyone involved, a man now stepped onto the stage who was willing to confront the seemingly insoluble contradictions of Soviet society. On March 11, 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev was named General Secretary of the Communist Party, the eighth and, as it would transpire, the last leader of the Soviet Union. He almost immediately signaled a new official position toward computing, as he did toward so many other things. In one of his first major policy speeches just weeks after assuming power, Gorbachev announced a plan to put personal computers into every classroom in the Soviet Union.

Unlike the General Secretaries who had come before him, Gorbachev recognized that the problems of rampant corruption and poor economic performance which had dogged the Soviet Union throughout its existence were not obstacles external to the top-down collectivist state envisioned by Vladimir Lenin but its inevitable results. “Glasnost,” the introduction of unprecedented levels of personal freedom, and “Perestroika,” the gradual replacement of the planned economy with a more market-oriented version permitting a degree of private ownership, were his responses. These changes would snowball in a way that no one — certainly not Gorbachev himself — had quite anticipated, leading to the effective dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the end of the Cold War before the 1980s were over. Unnerved by it all though he was, Gorbachev, to his everlasting credit, let it happen, rejecting the calls for a crackdown like those that had ended the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and the Prague Spring of 1968 in such heartbreak and tragedy.

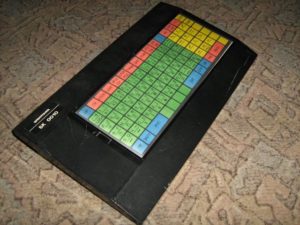

Very early in Gorbachev’s tenure, well before its full import had even started to become clear, it became at least theoretically possible for the first time for individuals in the Soviet Union to buy a private computer of their own for use in the home. Said opportunity came in the form of the Elektronika BK-0010. Costing about one-fifth as much as the Agat, the BK-0010 was a predictably slapdash product in some areas, such as its horrid membrane keyboard. In other ways, though, it impressed far more than anyone had a right to expect. The BK-0010, the very first Soviet microcomputer designed to be a home computer, was a 16-bit machine, placing it in this respect at least ahead of the typical Western Apple II, Commodore 64, or Sinclair Spectrum of the time. The microprocessor inside it was a largely original creation, borrowing the instruction set from the DEC PDP-11 line of minicomputers but borrowing its actual circuitry from no one. The Soviets’ struggles to stamp out the ever denser circuitry of the latest Western CPUs in their obsolete factories was ironically forcing them to be more innovative, to start designing chips of their own which their factories could manage to produce.

Supplies of the BK-0010 were always chronically short and the waiting lists long, but as early as 1985 a few lucky Soviet households could boast real, usable computers. Those who were less lucky might be able to build a bare-bones computer from schematics published in do-it-yourself technology magazines like Tekhnika Molodezhi, the Soviet equivalent to Popular Electronics. Just as had happened in the United States, Britain, and many other Western countries, a vibrant culture of hobbyist computing spread across the Soviet Union and the other Warsaw Pact nations. In time, as the technology advanced in rhythm with Perestroika, these hobbyists would become the founding spirits of a new Soviet computer industry — a capitalist computer industry. “These are people who have felt useless — useless — all their lives!” said American business pundit Esther Dyson after a junket to a changing Eastern Europe. “Do you know what it is like to feel useless all your life? Computers are turning many of these people into entrepreneurs. They are creating the entrepreneurs these countries need.” As one glance at the flourishing underground economy of the Soviet Union of any era had always been enough to prove, Russians had a natural instinct for capitalism. Now, they were getting the chance to exercise it.

In August of 1988, in a surreal sign of these changing times, a delegation including many senior members of the Soviet Academy of Sciences — the most influential theoretical voice in Soviet computing dating back to the early 1950s — arrived in New York City on a mission that would have been unimaginable just a couple of years before. To a packed room of technology journalists — the Mirror World remained as fascinating as ever — they demonstrated a variety of software which they hoped to sell to the West: an equation solver; a database responsive to natural-language input; a project manager; an economic-modelling package. Byte magazine called the presentation “clever, flashy, and unabashedly commercial,” with “lots of colored windows popping up everywhere” and lots of sound effects. The next few years would bring several ventures which served to prove to any doubters from that initial gathering that the Soviets were capable of programming world-class software if given half a chance. In 1991, for instance, Soviet researchers sold a system of handwriting recognition to Apple for use in the pioneering Apple Newton personal digital assistant. Reflecting the odd blend of greed and idealism that marked the era, a Russian programmer wrote to Byte magazine that “I do hope the world software market will be the only battlefield for American and Soviet programmers and that we’ll become friends during this new battle now that we’ve stopped wasting our intellects on the senseless weapons race.”

As it would transpire, though, the greatest Russian weapon in this new era of happy capitalism wasn’t a database, a project manager, or even a handwriting-recognition system. It was instead a game — a piece of software far simpler than any of those aforementioned things but with perhaps more inscrutable genius than all of them put together. Its unlikely story is next.

(Sources: the academic-journal articles “Soviet Computing and Technology Transfer: An Overview” by S.E. Goodman, “InterNyet: Why the Soviet Union Did Not Build a Nationwide Computer Network” by Slava Gerovitch, “The Soviet Bloc’s Unified System of Computers” by N.C. Davis and S.E. Goodman; the January 1970 and May 1972 issues of Rand Corporation’s Soviet Cybernetics Review; The New York Times of August 28 1966, May 7 1973, and November 27 1979; Scientific American of October 1970; Bloomberg Businessweek of November 4 1991; Byte of August 1980, April 1984, November 1984, July 1985, November 1986, February 1987, October 1988, and April 1989; a video recording the Computer History Museum’s commemoration of the IBM System/360 on April 7 2004. Finally, my huge thanks to Peter Sovietov, who grew up in the Soviet Union of the 1980s and the Russia of the 1990s and has been an invaluable help in sharing his memories and his knowledge and saving me from some embarrassing errors.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Some in the Soviet space program actually laid their failure to get to the Moon, perhaps a bit too conveniently, directly at the feet of the computer technology they were provided, noting that the lack of computers on the ground equal to those employed by NASA — which happened to be System/360s — had been a crippling disadvantage. Meanwhile the computers that went into space with the Soviets were bigger, heavier, and less capable than their American counterparts. |

|---|