When Brian Fargo made the bold decision in 1988 to turn his company Interplay into a computer-game publisher as well as developer, he was simply steering onto the course that struck him as most likely to ensure Interplay’s survival. Interplay had created one of the more popular computer games of the 1980s in the form of the 400,000-plus-selling CRPG The Bard’s Tale, yet had remained a tiny company living hand-to-mouth while their publisher Electronic Arts sucked up the lion’s share of the profits. And rankling almost as much as that disparity was the fact that Electronic Arts sucked up the lion’s share of the credit as well; very few gamers even recognized the name of Interplay in 1988. If this was what it was like to be an indentured developer immediately after making the best-selling single CRPG of the 1980s, what would it be like when The Bard’s Tale faded into ancient history? The odds of making it as an independent publisher may not have looked great, but from some angles at least they looked better than Interplay’s prospects if the status quo was allowed to continue.

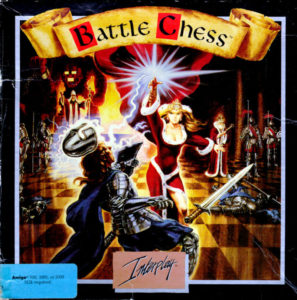

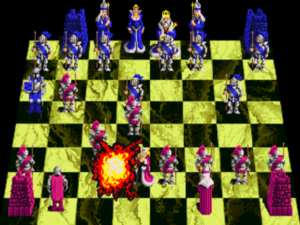

Having taken their leave of Electronic Arts and signed on as an affiliated label with Mediagenic in order to piggyback on the latter’s distribution network, the newly independent Interplay made their public bow by releasing two games simultaneously. One of these was Neuromancer, a formally ambitious, long-in-the-works adaptation of the landmark William Gibson novel. The other was the less formally ambitious Battle Chess, an initially Commodore Amiga-based implementation of chess in which the pieces didn’t just slide into position each time a player made a move but rather walked around the board to do animated battle. Not a patch on hardcore computerized chess games like The Chessmaster 2000 in terms of artificial intelligence — its chess-playing engine actually had its origin in a simple chess implementation released in source-code form by Borland to demonstrate their Turbo Pascal programming language [1]The later Apple II and Commodore 64 ports of the game ironically played a much stronger game of chess despite running on much more limited hardware. For them, Interplay licensed a chess engine from Julio Kaplan, an International Chess Master and former World Junior Chess Champion who had had written the firmware for a number of custom chess-playing computers and served as an all-purpose computer-chess consultant for years. — Battle Chess sold far better than any of them. Owners of Amigas were always eager for opportunities to show off their machines’ spectacular audiovisual capabilities, and Battle Chess delivered on that in spades, becoming one of the Amiga’s iconic games; it even featured prominently in a Computer Chronicles television episode about the Amiga. Today, long after its graphics have lost their power to wow us, it may be a little hard to understand why so many people were so excited about this slow-playing, gussied-up version of chess. Battle Chess, in other words, is unusually of-its-time even by the standards of old computer games. In its time, though, it delivered exactly what Interplay most needed as they stepped out on their own: it joined The Bard’s Tale to become the second major hit of their history, allowing them to firmly establish their footing on this new frontier of software publishing.

The King takes out a Knight in Battle Chess by setting off a bomb. Terrorism being what it is, this would not, needless to say, appear in the game if it was released today.

The remarkable success of Battle Chess notwithstanding, Interplay was hardly ready to abandon CRPGs — not after the huge sales racked up by The Bard’s Tale and the somewhat fewer but still substantial sales enjoyed by The Bard’s Tale II, The Bard’s Tale III, and Wasteland. Unfortunately, leaving Electronic Arts behind had also meant leaving those franchises behind; as was typical of publisher/developer relationships of the time, those trademarks had been registered by Electronic Arts, not Interplay. Faced with this reality, Interplay embarked on the difficult challenge of interesting gamers in an entirely new name on the CRPG front. Which isn’t to say that the new game would have nothing in common with what they’d done before. On the contrary, Interplay’s next CRPG was conceived as a marriage of the fantasy setting of The Bard’s Tale, which remained far more popular with gamers than alternative settings, with the more sophisticated game play of the post-apocalyptic Wasteland, which had dared to go beyond mowing down hordes of monsters as its be-all end-all.

Following a precedent he had established with Wasteland, Fargo hired established veterans of the tabletop-RPG industry to design the new game. But in lieu of Michael Stackpole and Ken St. Andre, this time he went with Steve Peterson and Paul Ryan O’Connor. The former was best known as the designer of 1981’s Champions, one of the first superhero RPGs and by far the most popular prior to TSR entering the fray with the official Marvel Comics license in 1984. The latter was yet another of the old Flying Buffalo crowd who had done so much to create Wasteland; at Flying Buffalo, O’Connor had been best known as the originator of the much-loved and oft-hilarious Grimtooth’s Traps series of supplements. In contrast to Stackpole and St. Andre, the two men didn’t work on Interplay’s latest CRPG simultaneously but rather linearly, with Peterson handing the design off to O’Connor after creating its core mechanics but before fleshing out its plot and setting. Only quite late into O’Connor’s watch did the game, heretofore known only as “Project X,” finally pick up its rather generic-sounding name of Dragon Wars.

At a casual glance, Dragon Wars‘s cheesecake cover art looks like that of any number of CRPGs of its day. But for this game, Brian Fargo went straight to the wellspring of cheesecake fantasy art, commissioning Boris Vallejo himself to paint the cover. The end results set Interplay back $4000. You can judge for yourself whether it was money well-spent.

A list of Interplay’s goals for Dragon Wars reads as follows:

- Deemphasis of “levels” — less of a difference in ability from one level to another.

- Experience for something besides killing.

- No random treasure — limit it such as Wasteland’s.

- Ability to print maps (dump to printer).

- Do something that has an effect — it does not necessarily have to be done to win (howitzer shell in Wasteland that blows up fast-food joint).

- Characters should not begin as incompetents — thieves that disarm traps only 7 percent of the time, etc. Fantasy Hero/GURPS levels of competence at the start are more appropriate (50 percent or better success rate to start with).

- Reduce bewildering array of slightly different spells.

- If character “classes” are to be used, they should all be distinctive and different from each other and useful. None, however, should be absolutely vital.

- Less linear puzzles — there should be a number of quests that can be done at any given time.

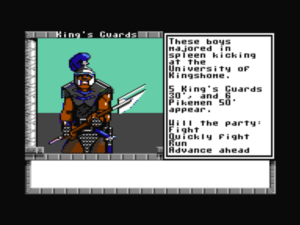

The finished game hews to these goals fairly well, and to fairly impressive effect. The skill-based — as opposed to class-based — character system of Wasteland is retained, and there are multiple approaches available at every turn. Dragon Wars still runs on 8-bit computers like the Apple II and Commodore 64 in addition to more advanced machines, but it’s obvious throughout that Interplay has taken steps to remedy the shortcomings of their previous CRPGs as much as possible within the limitations of 8-bit technology. For instance, there’s an auto-map system included which, limited though it is, shows that they were indeed trying. As with Wasteland, an obvious priority is to bring more of the tabletop experience to the computer. Another priority, though, is new: to throttle back the pace of character development, thus steering around the “Monty Haul” approach so typical of CRPGs. Characters do gain in levels and thus in power in Dragon Wars, but only very slowly, while the game is notably stingy with the gold and magic that fill most CRPGs from wall to wall. Since leveling up and finding neat loot is such a core part of the joy of CRPGs for so many of us, these choices inevitably lead to a game that’s a bit of an acquired taste. That reality, combined with the fact that the game does no hand-holding whatsoever when it comes to building your characters or anything else — it’s so tough to create a viable party of your own out of the bewildering list of possible skills that contemporary reviewers recommended just playing with the included sample party — make it a game best suited for hardened old-school CRPG veterans. That said, it should also be said that many in that select group consider Dragon Wars a classic.

Dragon Wars would mark the end of the line for Interplay games on 8-bit home computers. From now on, MS-DOS and consoles would dominate, with an occasional afterthought of an Amiga version.

The game didn’t do very well at retail, but that situation probably had more to do with external than intrinsic factors. It was introduced as yet another new name into a CRPG market that was drowning in more games than even the most hardcore fan could possibly play. And for all Interplay’s determination to advance the state of the art over The Bard’s Tale games and even Wasteland, Dragon Wars was all too obviously an 8-bit CRPG at a time when the 8-bit market was collapsing.

In the wake of Dragon Wars‘s underwhelming reception, Interplay was forced to accept that the basic technical approach they had used with such success in all three Bard’s Tale games and Wasteland had to give way to something else, just as the 8-bit machines that had brought them this far had to fall by the wayside. Sometimes called The Bard’s Tale IV by fans — it would doubtless have been given that name had Interplay stayed with Electronic Arts — Dragon Wars was indeed the ultimate evolution of what Interplay had begun with the original Bard’s Tale. It was also, however, the end of that particular evolutionary branch of the CRPG.

Luckily, the ever industrious Brian Fargo had something entirely new in the works in the realm of CRPGs. And, as had become par for the course, that something would involve a veteran of the tabletop world.

Paul Jaquays [2]Paul Jaquays now lives as Jennell Jaquays. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. had discovered Dungeons & Dragons in 1975 in his first year of art college and never looked back. After founding The Dungeoneer, one of the young industry’s most popular early fanzines, he kicked around as a free-lance writer, designer, and illustrator, coming to know most of the other tabletop veterans we’ve already met in the context of their work with Interplay. Then he spent the first half of the 1980s working on videogames for Coleco; he was brought on there by none other than Wasteland designer Michael Stackpole. Jaquays, however, remained at Coleco much longer than Stackpole, rising to head their design department. When Coleco gave up on their ColecoVision console and laid off their design staff in 1985, Jaquays went back to freelancing in both tabletop and digital gaming. Thus it came to pass that Brian Fargo signed him up to make Interplay’s next CRPG while Dragon Wars was still in production. The game was to be called Secrets of the Magi. While it was to have run on the 8-bit Commodore 64 among other platforms, it was planned as a fast-paced, real-time affair, in marked contrast to Interplay’s other CRPGs, with free-scrolling movement replacing their grid-based movement, action-oriented combat replacing their turn-based combat. But the combination of the commercial disappointment that had been Dragon Wars and the collapse of the 8-bit market which it signified combined with an entirely new development to change most of those plans. Jaquays was told one day by one of Magi‘s programmers that “we’re not doing this anymore. We’re doing a Lord of the Rings game.”

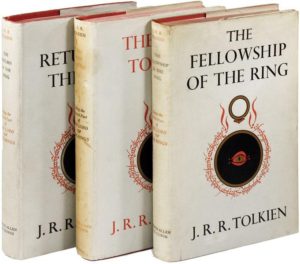

Fargo’s eyes had been opened to the possibilities for literary adaptations by his friendship with Timothy Leary, which had led directly to Interplay’s adaptation of Neuromancer and, more indirectly but more importantly in this context, taught him something about wheeling and dealing with the established powers of Old Media. At the time, the Tolkien estate, the holders of J.R.R. Tolkien’s literary copyrights, were by tacit agreement with Tolkien Enterprises, holders of the film license, the people to talk to if you wanted to create a computer game based on Tolkien. The only publisher that had yet released such a beast was Australia’s Melbourne House, who over the course of the 1980s had published four text adventures and a grand-strategy game set in Middle-earth. But theirs wasn’t an ongoing licensing arrangement; it had been negotiated anew for each successive game. And they hadn’t managed to make a Tolkien game that became a notable critical or commercial success since their very first one, a text-adventure adaptation of The Hobbit from way back in 1982. In light of all this, there seemed ample reason to believe that the Tolkien estate might be amenable to changing horses. So, Brian Fargo called them up and asked if he could make a pitch.

Fargo told me recently that he believes it was his “passion” for the source material that sealed the deal. Fargo:

I had obsessed over the books when I was little, had the calendar and everything. And inside the front cover of The Fellowship of the Ring was a computer program I’d written down by hand when I was in seventh grade. I brought it to them and showed them: “This was my first computer program, written inside the cover of this book.” I don’t know if that’s what got them to agree, but they did. I think they knew they were dealing with people that were passionate about the license.

One has to suspect that Fargo’s honest desire to make a Lord of the Rings game for all the right reasons was indeed the determining factor. Christopher Tolkien, always the prime mover among J.R.R. Tolkien’s heirs, has always approached the question of adaptation with an eye to respecting and preserving the original literary works above all other considerations. And certainly the Tolkien estate must have seen little reason to remain loyal to Melbourne House, whose own adaptations had grown so increasingly lackluster since the glory days of their first Hobbit text adventure.

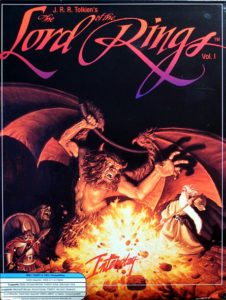

A bemused but more than willing Paul Jacquays thus saw his Secrets of the Magi transformed into a game with the long-winded title — licensing deals produce nothing if not long-winded titles — of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Volume 1. (For some reason known only to the legal staff, the name The Fellowship of the Ring wasn’t used, even though the part of Tolkien’s story covered by the game dovetails almost perfectly with the part covered by that first book in the trilogy.) While some of the ideas that were to have gone into Jaquays’s original plan for Secrets of the Magi were retained, such as the real-time play and free-scrolling movement, the game would now be made for MS-DOS rather than the Commodore 64. Combined with the Tolkien license, which elevated the game at a stroke to the status of the most high-profile ongoing project at Interplay, the switch in platforms led to a dramatic up-scaling in ambition.

Thrilled though everyone had been to acquire the license, making The Lord of the Rings, by far the biggest thing Interplay had ever done in terms of sheer amount of content, turned into a difficult grind that was deeply affected by external events, starting with a certain crisis of identity and ending with a full-blown existential threat.

Like so many American computer-game executives at the time, Brian Fargo found the Nintendo Entertainment System and its tens of millions of active players hard to resist. While one piece of his company was busy making The Lord of the Rings into a game, he therefore set another piece to work churning out Interplay’s first three Nintendo games. Having no deal with the notoriously fickle Nintendo and thus no way to enter their walled garden as a publisher in their own right, Interplay was forced to publish two of these games through Mediagenic’s Activision label, the other through Acclaim Entertainment. Unfortunately, Fargo was also like many other computer-game executives in discovering to his dismay that there was far more artistry to Nintendo hits like Super Mario Bros. than their surface simplicity might imply — and that Nintendo gamers, young though they mostly were, were far from undiscerning. None of Interplay’s Nintendo games did very well at all, which in turn did no favors to Interplay’s bottom line.

Interplay sorely needed another big hit like Battle Chess, but it was proving damnably hard to find. Even the inevitable Battle Chess II: Chinese Chess performed only moderately. The downside of a zeitgeist-in-a-bottle product like Battle Chess was that it came with a built-in sell-by date. There just wasn’t that much to be done to build on the original game’s popularity other than re-skinning it with new graphics, and the brief-lived historical instant when animated chessmen were enough to sell a game was already passing.

Then, in the midst of these other struggles, Interplay was very nearly buried by the collapse of Mediagenic in 1990. I’ve already described the reasons for that collapse and much of the effect it had on Interplay and the rest of the industry in an earlier article, so I won’t retread that ground in detail here. Instead I’ll just reiterate that the effect was devastating for Interplay. With the exception only of the single Nintendo game published through Acclaim and the trickle of royalties still coming in from Electronic Arts for their old titles, Interplay’s entire revenue stream had come through Mediagenic. Now that stream had run dry as the Sahara. In the face of almost no income whatsoever, Brian Fargo struggled to keep Interplay’s doors open, to keep his extant projects on track, and to establish his own distribution channel to replace the one he had been renting from Mediagenic. His company mired in the most serious crisis it had ever faced, Fargo went to his shareholders — Interplay still being privately held, these consisted largely of friends, family, and colleagues — to ask for the money he needed to keep it alive. He managed to raise over $500,000 in short-term notes from them, along with almost $200,000 in bank loans, enough to get Interplay through 1990 and get the Lord of the Rings game finished. The Lord of the Rings game, in other words, had been elevated by the misfortunes of 1990 from an important project to a bet-the-company project. It was to be finished in time for the Christmas of 1990, and if it became a hit then Interplay might just live to make more games. And if not… it didn’t bear thinking about.

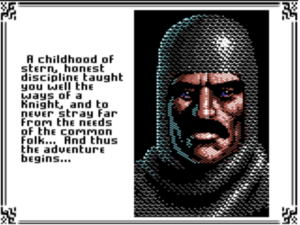

The Lord of the Rings‘s free-scrolling movement and overhead perspective were very different from what had come before, ironically resembling Origin’s Ultima games more than Interplay’s earlier CRPGs. But the decision to have the interface get out of the way when it wasn’t needed, thus giving more space to the world, was very welcome, especially in comparison to the cluttered Ultima VI engine. Interplay’s approach may well have influenced Ultima VII.

If a certain technical approach to the CRPG — a certain look and feel, if you will — can be seen as having been born with the first Bard’s Tale and died after Dragon Wars, a certain philosophical approach can be seen just as validly as having been born with Wasteland and still being alive and well at Interplay at the time of The Lord of the Rings. The design of the latter would once again emphasize character skills rather than character class, and much of the game play would once again revolve around applying your party’s suite of skills to the situations encountered. Wasteland‘s approach to experience and leveling up had been fairly traditional; characters increased in power relatively quickly, especially during the early stages of the game, and could become veritable demigods by the end. Dragon Wars, though, had departed from tradition by slowing this process dramatically, and now The Lord of the Rings would eliminate the concept of character level entirely; skills would still increase with use, but only slowly, and only quietly behind the scenes. These mechanical changes would make the game unlike virtually any CRPG that had come before it, to such an extent that some have argued over whether it quite manages to qualify as a CRPG at all. It radically de-emphasizes the character-building aspect of the genre — you don’t get to make your own characters at all, but start out in the Shire with only Frodo and assemble a party over the course of your travels — and with it the tactical min/maxing that is normally such a big part of old-school CRPGs. As I noted in my previous article, Middle-earth isn’t terribly well-suited to traditional RPG mechanics. The choice Interplay made to focus less on mechanics and more on story and exploration feels like a logical response, an attempt to make a game that does embody Tolkien’s ethos.

In addition to the unique challenges of adapting CRPG mechanics to reflect the spirit of Middle-earth, Interplay’s Lord of the Rings game faced all the more typical challenges of adapting a novel to interactive form. To simply walk the player through the events of the book would be uninteresting and, given the amount of texture and exposition that would be lost in the transition from novel to game, would yield far too short of an experience. Interplay’s solution was to tackle the novel in terms of geography rather than plot. They created seven large maps for you to progress through, covering the stages of Frodo and company’s journey in the novel: the Shire, the Old Forest, Bree, Rivendell, Moria, Lothlórien, and Dol Guldur. (The last reflects the game’s only complete deviation from the novel; for its climax, it replaces the psychological drama of Boromir’s betrayal of the Fellowship with a more ludically conventional climactic assault on the fortress of the Witch-King of Angmar — the Lord of the Nazgûl — who has abducted Frodo.) Paul Jaquays scattered episodes from the novel over the maps in what seemed the most logical places. Then, he went further, adding all sorts of new content.

Interplay understood that reenacting the plot of the novel wasn’t really what players would find most appealing about a CRPG set in Middle-earth. The real appeal was that of simply wandering about in the most beloved landscapes in all of fantasy fiction. For all that the Fellowship was supposed to be on a desperate journey to rid the world of its greatest threat in many generations, with the forces of evil hot on their trail, it wouldn’t do to overemphasize that aspect of the book. Players would want to stop and smell the roses. Jaquays therefore stuffed each of the maps with content, almost all of it optional; there’s very little that you need to do to finish the game. While a player who takes the premise a bit too literally could presumably rush through the maps in a mere handful of hours, the game clearly wants you to linger over its geography, scouring it from end to end to see what you can turn up.

In crafting the maps, and especially in crafting the new content on them, Jaquays was hugely indebted to Iron Crown Enterprises’s Middle-earth Role Playing tabletop RPG and its many source books which filled in the many corners of Middle-earth in even greater detail than Tolkien had managed in his voluminous notes. For legal reasons — Interplay had bought a Fellowship of the Ring novel license, not a Middle-earth Role Playing game license — care had to be taken not to lift anything too blatantly, but anyone familiar with Iron Crown’s game and Interplay’s game can’t help but notice the similarities. The latter’s vision of Middle-earth is almost as indebted to the former as it is to Tolkien himself. One might say that it plays like an interactive version of one of those Iron Crown source books.

Conversation takes the Ultima “guess the keyword” approach. Sigh… at least you can usually identify topics by watching for capitalized words in the text.

Interplay finished development on the game in a mad frenzy, with the company in full crisis mode, trying to get it done in time for the Christmas of 1990. But in the end, they were forced to make the painful decision to miss that deadline, allowing the release date to slip to the beginning of 1991. Then, with it shipping at last, they waited to see whether their bet-the-company game would indeed save their skins. Early results were not encouraging.

Once you got beyond the awful, unwieldy name, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Volume 1 seemingly had everything going for it: a developer with heaps of passion and heaps of experience making CRPGs, a state-of-the-art free-scrolling engine with full-screen graphics, and of course a license for the most universally known and beloved series of books in all of fantasy fiction. It ought to have been a sure thing, a guaranteed hit if ever there was one. All of which makes its reception and subsequent reputation all the more surprising. If it wasn’t quite greeted with a collective shrug, Interplay’s first Tolkien game was treated with far more skepticism than its pedigree might lead one to expect.

Some people were doubtful of the very idea of trying to adapt Tolkien, that most holy name in the field of fantasy, into a game in much the same way that some Christians might be doubtful of making Jesus Christ the star of a game. For those concerned above all else with preserving the integrity of the original novel, Interplay’s approach to the task of adaptation could only be aggravating. Paul Jaquays had many talents, but he wasn’t J.R.R. Tolkien, and the divisions between content drawn from the books and new content were never hard to spot. What right had a bunch of game developers to add on to Middle-earth? It’s a question, of course, with no good answer.

But even those who were more accepting of the idea of The Lord of the Rings in game form found a lot of reasons to complain about this particular implementation of the idea. The most immediately obvious issue was the welter of bugs. Bugs in general were becoming a more and more marked problem in the industry as a whole as developers strained to churn out ever bigger games capable of running on an ever more diverse collection of MS-DOS computing hardware. Still, even in comparison to its peers Interplay’s Lord of the Rings game is an outlier, being riddled with quests that can’t be completed, areas that can’t be accessed, dialog that doesn’t make sense. Its one saving grace is the generosity and flexibility that Jaquays baked into the design, which makes it possible to complete the game even though it can sometimes seem like at least half of it is broken in one way or another. A few more months all too obviously should have been appended to the project, even if it was already well behind schedule. Given the state of the game Interplay released in January of 1991, one shudders to think what they had seriously considered rushing to market during the holiday season.

You’ll spend a lot of time playing matchy-matchy with lists of potentially applicable skills. A mechanic directly imported from tabletop RPGs, it isn’t the best fit for a computer game, for reasons I explicated in my article on Wasteland.

Other issues aren’t quite bugs in the traditional sense, but do nevertheless feel like artifacts of the rushed development cycle. The pop-up interface which overlays the full-screen graphics was innovative in its day, but it’s also far more awkward to use than it needs to be, feeling more than a little unfinished. It’s often too difficult to translate actions into the terms of the interface, a problem that’s also present in Wasteland and Dragon Wars but is even more noticeable here. Good, logical responses to many situations — responses which are actually supported by the game — can fall by the wayside because you fail to translate them correctly into the terms of the tortured interface. Throwing some food to a band of wolves to make them go away rather than attack you early in the game, for instance, requires you divine that you need to “trade” the food to them. Few things are more frustrating than looking up the solution to a problem like this one and learning that you went awry because you “used” food on the wolves instead of “trading” it to them.

But perhaps the most annoying issue is that of simply finding your way around. Each of those seven maps is a big place, and no auto-map facility is provided; Interplay had intended to include such a feature, but dropped it in the name of saving time. The manual does provide a map of the Shire, but after that you’re on your own. With paper-and-pencil mapping made damnably difficult by the free-scrolling movement that it makes it impossible to accurately judge distances, just figuring out where you are, where you’ve been, and where you need to go often turns into the most challenging aspect of the game.

Combat can be kind of excruciating, especially when you’re stuck with nothing but a bunch of hobbits.

It all adds up to something of a noble failure — a game which, despite the best intentions of everyone involved, just isn’t as magical as it ought to have been. The game sold in moderate numbers on the strength of the license, but, its commercial prospects damaged as much by missing the Christmas buying season as by the lukewarm reviews, it never became the major hit Interplay so desperately needed. That disappointment may very well have marked the end of Interplay, if not for a stroke of good fortune from a most unexpected quarter.

Shortly after electing to turn Interplay into an independent publisher, Brian Fargo had begun looking for more games to publish beyond those his small internal team could develop. He’d found some worthwhile titles, albeit titles reflective of the small size and relative lack of clout of his company: a classical chess game designed to appeal to those uninterested in Battle Chess‘s eye-candy approach; a series of typing tutors; a clever word game created by a couple of refugees from the now-defunct Cinemaware; a series of European imports sourced through France’s Delphine Software. None had set the world on fire, but then no one had really expected them to.

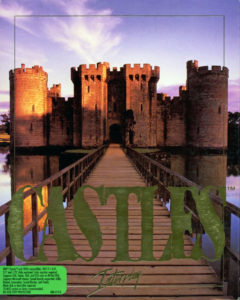

That all changed when Interplay agreed to publish a game called Castles, from a group of outside developers who called themselves Quicksilver Software. Drawing from King Edward I of England’s castle-building campaign in Wales for its historical antecedent, Castles at its core was essentially a Medieval take on SimCity. Onto this template, however, Quicksilver grafted the traditional game elements some had found lacking in Will Wright’s software toy. The player’s castles would be occasionally attacked by enemy armies, forcing her to defend them in simple tactical battles, and she would also have to deal with the oft-conflicting demands of the clergy, the nobility, and the peasantry in embodied exchanges that gave the game a splash of narrative interest. Not a deathless classic by any means, it was a game that just about everyone could while away a few hours with. Castles was able to attract the building crowd who loved SimCity, the grognard crowd who found its historical scenario appealing, the adventure and CRPG crowd who liked the idea of playing the role of a castle’s chief steward, while finishing the mixture off with a salting of educational appeal. With some of the most striking cover art of any game released that year to serve as the finishing touch, its combination of appeals proved surprisingly potent. In fact, no one was more surprised by the game’s success than Interplay, who, upon releasing Castles just weeks after the Lord of the Rings game, found themselves with an unexpected but well-nigh life-saving hit on their hands. Every time you thought you understood gamers, Brian Fargo was continuing to learn, they’d turn around and surprise you.

So, thanks to this most fortuitous of saviors, Interplay got to live on. Almost in spite of himself, Fargo continued to pull a hit out of his sleeve every two or three years, always just when his company most needed one. He’d done it with The Bard’s Tale, he’d done it with Battle Chess, and now he’d done it with Castles.

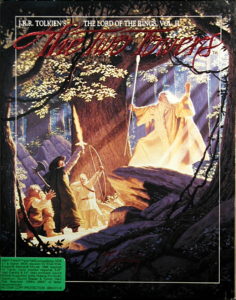

Castles had rather stolen The Lord of the Rings‘s thunder, but Interplay pressed on with the second game in the trilogy, which was allowed the name The Two Towers to match that of its source novel. Released in August of 1992 after many delays, it’s very similar in form and execution to its predecessor — including, alas, lots more bugs — despite the replacement of Paul Jaquays with a team of designers that this time included Ed Greenwood, one of the more prominent creative figures of the post-Gary Gygax era of TSR. Interplay did try to address some of the complaints about the previous game by improving the interface, by making the discrete maps smaller and thus more manageable, and by including the auto-mapping feature that had been planned for but left out of its predecessor. But it still wasn’t enough. Reviewers were even more unkind to the sequel despite Interplay’s efforts, and it sold even worse. By this point, Interplay had scored another big hit with Star Trek: 25th Anniversary, the first officially licensed Star Trek game to be worthy of the name, and had other projects on the horizon that felt far more in keeping with the direction the industry was going than did yet another sprawling Middle-earth CRPG. Brian Fargo’s passion for Tolkien may have been genuine, but at some point in business passion has to give way to financial logic. Interplay’s vision of The Lord of the Rings was thus quietly abandoned at the two-thirds mark.

In a final bid to eke a bit more out of it, Interplay in 1993 repackaged the first Lord of the Rings game for CD-ROM, adding an orchestral soundtrack and interspersing the action, rather jarringly, with clips from Ralph Bakshi’s 1978 animated Lord of the Rings film, which Fargo had also managed to license. But the most welcome improvement came in the form of a slightly more advanced game engine, including an auto-map. Despite the improvements, sales of this version were so poor that Interplay never bothered to give The Two Towers the CD-ROM treatment. A dire port/re-imagining of the first game for the Super Nintendo was the final nail in the coffin, marking the last gasp of Interplay’s take on Tolkien. Just as Bakshi had left his hobbits stranded on the way to Mordor when he failed to secure the financing to make his second Lord of the Rings movie, Interplay left theirs in limbo only a little closer to the Crack of Doom. The irony of this was by no means lost on so dedicated a Tolkien fan as Brian Fargo.

Unlike Dragon Wars, which despite its initial disappointing commercial performance has gone on to attain a cult-classic status among hardcore CRPG fans, the reputations of the two Interplay Lord of the Rings games have never been rehabilitated. Indeed, to a large extent the games have simply been forgotten, bizarre though that situation reads given their lineage in terms of both license and developer. Being neither truly, comprehensively bad games nor truly good ones, they fall into a middle ground of unmemorable mediocrity. In response to their poor reception by a changing marketplace, Interplay would all but abandon CRPGs for the next several years. The company The Bard’s Tale had built could now make a lot more money in other genres. If there’s one thing the brief marriage of Interplay with Tolkien demonstrates, it’s that a sure thing is never a sure thing.

(Sources: This article is largely drawn from the collection of documents that Brian Fargo donated to the Strong Museum of Play. Also, Questbusters of March 1989, December 1989, January 1991, June 1991, April 1992, and August 1992; Antic of July 1985; Commodore Magazine of October 1988; Creative Computing of September 1981; Computer Gaming World of December 1989 and September 1990. Online sources include a Jennell Jaquays Facebook posting and the Polygon article “There and Back Again: A History of The Lord of the Rings in Video Games.” Finally, my huge thanks to Brian Fargo for taking time from his busy schedule to discuss his memories of Interplay’s early days with me.

Neither of the two Interplay Lord of the Rings games have been available for purchase for a long, long time, a situation that is probably down to the fine print of the licensing deal that was made with the Tolkien estate all those years ago. I hesitate to host them here out of fear of angering either of the parties who signed that deal, but they aren’t hard to find elsewhere online with a little artful Googling.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The later Apple II and Commodore 64 ports of the game ironically played a much stronger game of chess despite running on much more limited hardware. For them, Interplay licensed a chess engine from Julio Kaplan, an International Chess Master and former World Junior Chess Champion who had had written the firmware for a number of custom chess-playing computers and served as an all-purpose computer-chess consultant for years. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Paul Jaquays now lives as Jennell Jaquays. As per my usual editorial policy on these matters, I refer to her as “he” and by her original name only to avoid historical anachronisms and to stay true to the context of the times. |