Rule #1 is “The Player Must have Fun.” It’s trivially easy for a game designer to “defeat” players. We have all the tools and all the power. The trick is to play on the same side as the players, to tell the story together, and to make them the stars.

That rule is probably the biggest differentiator that made our games special. We didn’t strive to make the toughest, hardest-to-solve puzzles. We focused on the characters, the stories, and making the player the star.

— Corey Cole

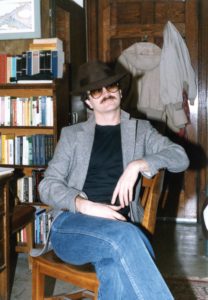

It feels thoroughly appropriate that Corey and Lori Ann Cole first met over a game of Dungeons & Dragons. The meeting in question took place at Westercon — the West Coast Science Fantasy Conference — in San Francisco in the summer of 1979. Corey was the Dungeon Master, leading a group of players through an original scenario of his own devising that he would later succeed in getting published as The Tower of Indomitable Circumstance. But on this occasion he found the pretty young woman who was sitting at his table even more interesting than Dungeons & Dragons. Undaunted by mere geography — Corey was programming computers for a living in Southern California while Lori taught school in Arizona — the two struck up a romantic relationship. Within a few years, they were married, settling eventually in San Jose.

They had much in common. As their mutual presence at a convention like Westercon will attest, both the current and the future Cole were lovers of science-fiction and fantasy literature and its frequent corollary, gaming, from well before their first meeting. Their earliest joint endeavor — besides, that is, the joint endeavor of romance — was The Spellbook, a newsletter for tabletop-RPG aficionados which they edited and self-published.

Corey also nurtured an abiding passion for computers that had long since turned into a career. After first learning to program in Fortran and COBOL while still in high school during the early 1970s, his subsequent experiences had constituted a veritable grand tour of some of the most significant developments of this formative decade of creative computing. He logged onto the ARPANET (predecessor of the modern Internet) from a terminal at his chosen alma mater, the University of California, Santa Barbara; played the original Adventure in the classic way, via a paper teletype machine; played games on the PLATO system, including the legendary proto-CRPGs Oubliette and DND that were hosted there. After graduating, he took a job with his father’s company, a manufacturer of computer terminals, traveling the country writing software for customers’ installations. By 1981, he had moved on to become a specialist in word-processing and typesetting software, all the while hacking code and playing games at home on his home-built CP/M computer and his Commodore PET.

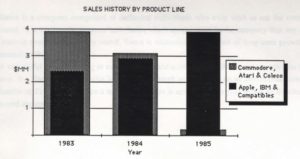

When the Atari ST was introduced in 1985, offering an unprecedented amount of power for the price, Corey saw in it the potential to become the everyday computer of the future. He threw himself into this latest passion with abandon, becoming an active member of the influential Bay Area Atari Users Group, a contributor to the new ST magazine STart, and even the founder of a new company, Visionary Systems; the particular vision in question was that of translating his professional programming experience into desktop-publishing software for the ST.

Interestingly, Corey’s passion for computers and computer games was largely not shared by Lori. Like many dedicated players of tabletop RPGs, she always felt the computerized variety to be lacking in texture, story, and most of all freedom. She could enjoy games like Wizardry in bursts with friends, but ultimately found them far too constraining to sustain her interest. And she felt equally frustrated by the limitations of both the parser-driven text adventures of Infocom and the graphical adventures of Sierra. Her disinterest in the status quo of computer gaming would soon prove an ironic asset, prompting her to push her own and Corey’s games in a different and very worthwhile direction.

By early 1988, it was becoming clear that the Atari ST was doomed to remain a niche platform in North America, and thus that Corey’s plan to get rich selling desktop-publishing software for it wasn’t likely to pan out. Meanwhile his chronic asthma was making it increasingly difficult to live in the crowded urban environs of San Jose. The Coles were at one of life’s proverbial crossroads, unsure what to do next.

Then one day they got a call from Carolly Hauksdottir, an old friend from science-fiction fandom — she wrote and sang filk songs with them — who happened to be working now as an artist for Sierra On-Line down in the rural paradise of Oakhurst, California. It seemed she had just come out of a meeting with Sierra’s management in which Ken Williams had stated emphatically that they needed to get back into the CRPG market. Since their brief association with Richard Garriott, which had led to their releasing Ultima II and re-releasing Ultima I, Sierra’s presence in CRPGs had amounted to a single game called Wrath of Denethenor, a middling effort for the Apple II and Commodore 64 sold to them by an outside developer. As that meager record will attest, Ken had never heretofore made the genre much of a priority. But of late the market for CRPGs showed signs of exploding, as evidenced by the huge success of other publishers’ releases like The Bard’s Tale and Ultima IV. To get themselves a piece of that action, Ken stated in his typical grandiose style that Sierra would need to hire “a published, award-winning, tournament-level Dungeon Master” and set him loose with their latest technology. Corey and Lori quickly reasoned that The Tower of Indomitable Circumstances had been published by the small tabletop publisher Judges Guild, as had their newsletter by themselves; that Corey had once won a tournament at Gen Con as a player; and that together they had once created and run a tournament scenario for a Doctor Who convention. Between the two of them, then, they were indeed “published, award-winning, tournament-level Dungeon Masters.” Right?

Well, perhaps they weren’t quite what Ken had in mind after all. When Corey called to offer their services, at any rate, he sounded decidedly skeptical. He was much more intrigued by another skill Corey mentioned in passing: his talent for programming the Atari ST. Sierra had exactly one programmer who knew anything about the ST, and was under the gun to get their new SCI engine ported over to that platform as quickly as possible. Ken wound up hiring Corey for this task, waving aside the initial reason for Corey’s call with the vague statement that “we’ll talk about game design later.”

What with Corey filling such an urgent need on another front, one can easily imagine Ken’s “later” never arriving at all. Corey, however, never stopped bringing up game design, and with it the talents of his wife that he thought would make her perfect for the role. While he thought that the SCI engine, despite its alleged universal applicability, could never be used to power a convincing hardcore CRPG of the Bard’s Tale/Ultima stripe, he did believe it could serve very well as the base for a hybrid game — part CRPG, part traditional Sierra adventure game. Such a hybrid would suit Lori just fine; her whole interest in the idea of designing computer games was “to bring storytelling and [the] interesting plot lines of books and tabletop role-playing into the hack-and-slash thrill of a computer game.” Given the technological constraints of the time, a hybrid actually seemed a far better vehicle for accomplishing that than a hardcore CRPG.

So, while Corey programmed in Sierra’s offices, Lori sat at home with their young son, sketching out a game. In fact, knowing that Sierra’s entire business model revolved around game series rather than one-offs, she sketched out a plan for four games, each taking place in a different milieu corresponding to one of the four points of the compass, one of the four seasons, and one of the four classical elements of Earth, Fire, Air, and Water. As was typical of CRPGs of this period, the player would be able to transfer the same character, evolving and growing in power all the while, into each successive game in the series.

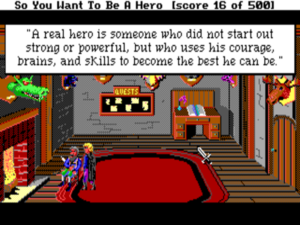

With his established tabletop-RPG designer still not having turned up, Ken finally relented and brought Lori on to make her hybrid game. But the programmer with whom she was initially teamed was very religious, and refused to continue when he learned that the player would have the option of choosing a “thief” class. And so, after finishing up some of his porting projects, Corey joined her on what they were now calling Hero’s Quest I: So You Want to Be a Hero. Painted in the broadest strokes, he became what he describes as the “left brain” to Lori’s “right brain” on the project, focusing on the details of systems and rules while Lori handled the broader aspects of plot and setting. Still, these generalized roles were by no means absolute. It was Corey, for instance, an incorrigible punster — so don’t incorrige him! — who contributed most of the horrid puns that abound throughout the finished game.

Less than hardcore though they envisioned their hybrid to be, Lori and Corey nevertheless wanted to do far more than simply graft a few statistics and a combat engine onto a typical Sierra adventure game. They would offer their player the choice of three classes, each with its own approach to solving problems: through combat and brute force in the case of the fighter, through spells in the case of the magic user, through finesse and trickery in the case of the thief. This meant that the Coles would in effect have to design Hero’s Quest three times, twining together an intricate tapestry of differing solutions to its problems. Considering this reality, one inevitably thinks of what Ron Gilbert said immediately after finishing Maniac Mansion, a game in which the player could select her own team of protagonists but one notably free of the additional complications engendered by Hero’s Quest‘s emergent CRPG mechanics: “I’m never doing that again!” The Coles, however, would not only do it again — in fact, four times more — but they would consistently do it well, succeeding at the tricky task of genre blending where designers as talented as Brian Moriarty had stumbled.

Instead of thinking in terms of “puzzles,” the Coles preferred to think in terms of “problems.” In Hero’s Quest, many of these problems can be treated like a traditional adventure-game puzzle and overcome using your own logic. But it’s often possible to power through the same problem using your character’s skills and abilities. This quality makes it blessedly difficult to get yourself well-and-truly, permanently stuck. Let’s say you need to get a fish from a fisherman in order to get past the bear who’s blocking your passage across a river. You might, in traditional adventure-game style, use another item you found somewhere to repair his leaky boat, thus causing him to give you a fish as a small token of his appreciation. But you might also, if your character’s intelligence score is high enough, be able to convince him to give you a fish through logical persuasion alone. Or you might bypass the whole question of the fish entirely if your character is strong and skilled enough to defeat the bear in combat. Moriarty’s Beyond Zork tries to accomplish a superficially similar blending of the hard-coded adventure game and the emergent CRPG, but does so far less flexibly, dividing its problems rather arbitrarily into those soluble by adventure-game means and those soluble by CRPG means. The result for the player is often confusion, as things that ought to work fail to do so simply because a problem fell into the wrong category. Hero’s Quest was the first to get the blending right.

Based on incremental skill and attribute improvements rather than employing the more monolithic level-based structure of Dungeons & Dragons, the core of the Hero’s Quest game system reached back to a system of tabletop rules the Coles had begun formulating years before setting to work on their first computer game. It has the advantage of offering nearly constant feedback, a nearly constant sense of progress even if you happen to be stuck on one of the more concrete problems in the game. Spend some time bashing monsters, and your character’s “weapons use” score along with his strength and agility will go up; practice throwing daggers on the game’s handy target range, and his “throwing” skill will increase a little with almost every toss. Although you choose a class for your character at the outset, there’s nothing preventing you from building up a magic user who’s also pretty handy with a sword, or a fighter who knows how to throw a spell or two. You’ll just have to sacrifice some points in the beginning to get a start in the non-core discipline, then keep on practicing.

If forced to choose one adjective to describe Hero’s Quest and the series it spawned as a whole, I would have to go with “generous” — not, as the regular readers among you can doubtless attest, an adjective I commonly apply to Sierra games in general. Hero’s Quest‘s generosity extends far beyond its lack of the sudden deaths, incomprehensible puzzles, hidden dead ends, and generalized player abuse that were so typical of Sierra designs. Departing from Sierra’s other series with their King Grahams, Rosellas, Roger Wilcos, and Larry Laffers, the Coles elected not to name or characterize their hero, preferring to let their players imagine and sculpt the character each of them wanted to play. Even within the framework of a given character class, alternate approaches and puzzle — er, problem — solutions abound, while the environment is fleshed-out to a degree unprecedented in a Sierra adventure game. Virtually every reasonable action, not to mention plenty of unreasonable ones, will give some sort of response, some acknowledgement of your cleverness, curiosity, or sense of humor. Almost any way you prefer to approach your role is viable. For instance, while it’s possible to leave behind a trail of monstrous carnage worthy of a Bard’s Tale game, it’s also possible to complete the entire game without taking a single life. The game is so responsive to your will that the few places where it does fall down a bit, such as in not allowing you to choose the sex of your character — resource constraints led the Coles to make the hero male-only — stand out more in contrast to how flexible the rest of this particular game is than they do in contrast to most other games of the period.

Hero’s Quest‘s message of positive empowerment feels particularly bracing in our current age of antiheroes and murky morality.

Indeed, Hero’s Quest is such a design outlier from the other Sierra games of its era that I contacted the Coles with the explicit goal of coming to understand just how it could have come out so differently. Corey took me back all the way to the mid-1970s, to one of his formative experiences as a computer programmer and game designer alike, when he wrote a simple player-versus-computer tic-tac-toe game for a time-shared system to which he had access. “Originally,” he says, “it played perfectly, always winning or drawing, and nobody played it for long. After I introduced random play errors by the computer, so that a lucky player could occasionally win, people got hooked on the game.” From this “ah-ha!” moment and a few others like it was born the Coles’ Rule #1 for game design: “The player must always have fun.” “We try to remember that rule,” says Corey, “every time we create a potentially frustrating puzzle.” The trick, as he describes it, is to make “the puzzles and challenges feel difficult, yet give the player a chance to succeed after reasonable effort.” Which leads us to Rule #2: “The player wants to win.” “We aren’t here to antagonize the players,” he says. “We work with them in a cooperative storytelling effort. If the player fails, everybody loses; we want to see everyone win.”

Although their professional credits in the realm of game design were all but nonexistent at the time they came to Sierra, the Coles were nevertheless used to thinking about games far more deeply than was the norm in Oakhurst. They were, for one thing, dedicated players of games, very much in tune with the experience of being a player, whether sitting behind a table or a computer. Ken Williams, by contrast, had no interest in tabletop games, and had sat down and played for himself exactly one computerized adventure game in his life (that game being, characteristically for Ken, the ribald original Softporn). While Roberta Williams had been inspired to create Mystery House by the original Adventure and some of the early Scott Adams games, her experience as a player never extended much beyond those primitive early text adventures; she was soon telling interviewers that she “didn’t have the time” to actually play games. Most of Sierra’s other design staff came to the role through the back door of being working artists, writers, or programmers, not through the obvious front door of loving games as a pursuit unto themselves. Corey states bluntly that “almost nobody there played [emphasis mine] games.” The isolation from the ordinary player’s experience that led to so many bad designs was actually encouraged by Ken Williams; he suggested that his staffers not look too much at what the competition was doing out of some misguided desire to preserve the “originality” of Sierra’s own games.

But the Coles were a little different than the majority of said staffers. Corey points out that they were both over thirty by the time they started at Sierra. They had, he notes, also “traveled a fair amount,” and “both the real-life experience and extensive tabletop-gaming experience gave [us] a more ‘mature’ attitude toward game development, especially that the designer is a partner to the player, not an antagonist to be overcome.” Given the wealth of experience with games and ideas about how games ought to be that they brought with them to Sierra, the Coles probably benefited as much from the laissez-faire approach to game-making engendered by Ken Williams as some of the other designers perhaps suffered from the same lack of direction. Certainly Ken’s personal guidance was only sporadic, and often inconsistent. Corey:

Once in a while, Ken Williams would wander through the development area — it might happen two or three times in a day, or more likely the visits might be three weeks apart. Everyone learned that it was essential to show Ken some really cool sequence or feature that he hadn’t seen before. You only showed him one such sequence because you needed to reserve two more in case he came back the same day.

Our first (and Sierra’s first) Producer, Guruka Singh Khalsa, taught us the “Ken Williams Rule” based on something Robert Heinlein wrote: “That which he tells you three times is true.” Ken constantly came up with half-baked ideas, some of them amazing, some terrible, and some impractical. If he said something once, you nodded in agreement. Twice, you sat up and listened. Anything he said three times was law and had to be done. While Ken mostly played a management role at Sierra, he also had some great creative ideas that really improved our games. Of course, it takes fifteen seconds to express an idea, and sometimes days or weeks to make it work. That’s why we ignored the half-baked, non-repeated suggestions.

The Coles had no affinity for any of Sierra’s extant games; they considered them “unfair and not much fun.” Yet the process of game development at Sierra was so unstructured that they had little sense of really reacting against them either. As I mentioned earlier, Lori didn’t much care for any of the adventure games she had seen, from any company. She wouldn’t change her position until she played Lucasfilm Games’s The Secret of Monkey Island in 1990. After that experience, she became a great fan of the Lucasfilm adventures, enjoying them far more than the works of her fellow designers at Sierra. For now, though, rather than emulating existing computerized adventure or RPG games, the Coles strove to re-create the experience of sitting at a table with a great storytelling game master at its head.

Looking beyond issues of pure design, another sign of the Coles’ relatively broad experience in life and games can be seen in their choice of settings. Rather than settling for the generic “lazy Medieval” settings so typical of Dungeons & Dragons-derived computer games then and now, they planned their series as a hall of windows into some of the richest myths and legends of our own planet. The first game, which corresponded in Lori’s grand scheme for the series as a whole to the direction North, the season Spring, and the element Earth, is at first glance the most traditional of the series’s settings. This choice was very much a conscious one, planned to help the series attract an initial group of players and get some commercial traction; bullish as he was on series in general, Ken Williams wasn’t particularly noted for his patience with new ones that didn’t start pulling their own weight within a game or two. Look a little closer, though, and even the first game’s lush fantasy landscape, full of creatures that seem to have been lifted straight out of a Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual, stands out as fairly unique. Inspired by an interest in German culture that had its roots in the year Corey had spent as a high-school exchange student in West Berlin back in 1971 and 1972, the Coles made their Medieval setting distinctly Germanic, as is highlighted by the name of the town around which the action centers: Spielburg. (Needless to say, the same name is also an example of the Coles’ love of puns and pop-culture in-joking.) Later games would roam still much further afield from the lazy-Medieval norm. The second, for instance, moves into an Arabian Nights milieu, while still later ones explore the myths and legends of Africa, Eastern Europe, and Greece. The Coles’ determination to inject a little world music into the cultural soundtracks of their mostly young players stands out as downright noble. Their series doubtless prompted more than a few blinkered teenage boys to begin to realize what a big old interesting world there really is out there.

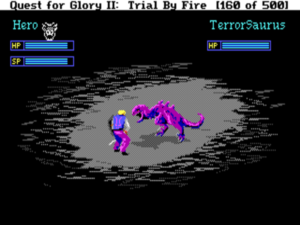

Of course, neither the first Hero’s Quest nor any of the later ones in the series would be entirely faultless. Sierra suffered from the persistent delusion that their SCI engine was a truly universal hammer suitable for every sort of nail, leading them to incorporate action sequences into almost every one of their adventure games. These are almost invariably excruciating, afflicted with slow response times and imprecise, clumsy controls. Hero’s Quest, alas, isn’t an exception from this dubious norm. It has an action-oriented combat engine so unresponsive that no one I’ve ever talked to tries to do anything with it but just pound on the “attack” key until the monster is dead or it’s obviously time to run away. And then there are some move-exactly-right-or-you’re-dead sequences in the end game that are almost as frustrating as some of the ones found in Sierra’s other series. But still, far more important in the end are all the things Hero’s Quest does right, and more often than not in marked contrast to just about every other Sierra game of its era.

Hero’s Quest was slated into Sierra’s release schedule for Christmas 1989, part of a diverse lineup of holiday releases that also included the third Leisure Suit Larry game from the ever-prolific Al Lowe and something called The Colonel’s Bequest, a bit of a departure for Roberta Williams in the form of an Agatha Christie-style cozy murder mystery. With no new King’s Quest game on offer that year, Hero’s Quest, the only fantasy release among Sierra’s 1989 lineup, rather unexpectedly took up much of its slack. As pre-orders piled up to such an extent that Sierra projected needing to press 100,000 copies right off the bat just to meet the holiday demand, Corey struggled desperately with a sequence — the kobold cave, for those of you who have played the game already — that just wouldn’t come together. At last he brokered a deal to withhold only the disk that would contain that sequence from the duplicators. In a single feverish week, he rewrote it from scratch. The withheld disk was then duplicated in time to join the rest, and the game as a whole shipped on schedule, largely if not entirely bug-free. Even more impressively, it was, despite receiving absolutely no outside beta-testing — Sierra still had no way of seriously evaluating ordinary players’ reactions to a game before release — every bit as friendly, flexible, and soluble as the Coles had always envisioned it to be.

The game became the hit its pre-orders had indicated it would, its sales outpacing even the new Leisure Suit Larry and Roberta Williams’s new game by a comfortable margin that holiday season. The reviews were superlative; Questbusters‘s reviewer pronounced it “honestly the most fun I’ve had with any game in years,” and Computer Gaming World made it their “Adventure Game of the Year.” While it would be nice to attribute this success entirely to the public embracing its fine design sensibilities, which they had learned of via all the fine reviews, its sales numbers undoubtedly had much to do with its good fortune in being released during this year without a King’s Quest. Hero’s Quest was for many a harried parent and greedy child alike the closest analogue to Roberta Williams’s blockbuster series among the new releases on store shelves. The game sold over 130,000 copies in its first year on the market, about 200,000 copies in all in its original version, then another 100,000 copies when it was remade in 1992 using Sierra’s latest technology. Such numbers were, if not quite in the same tier as a King’s Quest, certainly nothing to sneeze at. In creative and commercial terms alike, the Coles’ series was off to a fine start.

At the instant of Hero’s Quest‘s release, Sierra was just embarking on a major transition in their approach to game-making. Ken Williams had decided it was time at last to make the huge leap from the EGA graphics standard, which could display just 16 colors onscreen from a palette of 64, to VGA, which could display 256 colors from a palette of 262,144. To help accomplish this transition, he had hired Bill Davis, a seasoned Hollywood animator, in the new role of Sierra’s “Creative Director” in July of 1989. Davis systematized Sierra’s heretofore laissez-faire approach to game development into a rigidly formulated Hollywood-style production pipeline. Under his scheme, the artists would now be isolated from the programmers and designers; inter-team communication would happen only through a bureaucratic paper trail.

The changes inevitably disrupted Sierra’s game-making operation, which of late had been churning out new adventure games at a rate of about half a dozen per year. Many of the company’s resources for 1990 were being poured into King’s Quest V, which was intended, as had been the norm for that series since the beginning, to be the big showpiece game demonstrating all the company’s latest goodies, including not only 256-color VGA graphics but also a new Lucasfilm Games-style point-and-click interface in lieu of the old text parser. King’s Quest V would of course be Sierra’s big title for Christmas. They had only two other adventure games on their schedule for 1990, both begun using the older technology and development methodology well before the end of 1989 and both planned for release in the first half of the new year. One, an Arthurian game by an established writer for television named Christy Marx, was called Conquests of Camelot: The Search for the Grail (thus winning the prize of being the most strained application of Sierra’s cherished “Quest” moniker ever). The other, a foray into Tom Clancy-style techno-thriller territory by Police Quest designer Jim Walls, was called Code-Name: ICEMAN. Though they had every reason to believe that King’s Quest V would become another major hit, Sierra was decidedly uncertain about the prospects of these other two games. They felt they needed at least one more game in an established series if they hoped to maintain the commercial momentum they’d been building up in recent years. Yet it wasn’t clear where that game was to come from; one side effect of the transition to VGA graphics was that art took much longer to create, and games thus took longer to make. Lori and Corey were called into a meeting and given two options. One, which Lori at least remembers management being strongly in favor of, was to make the second game in their series using Sierra’s older EGA- and parser-driven technology, getting it out in time to become King’s Quest V‘s running mate for the Christmas of 1990. The other was to be moved in some capacity to the King’s Quest V project, with the opportunity to return to Hero’s Quest only at some uncertain future date. They chose — or were pushed into — the former.

Despite using the older technology, their second game was, at Davis’s insistence, created using the newer production methodology. This meant among other things that the artists, now isolated from the rest of the developers, had to create the background scenes on paper; their pictures were then scanned in for use in the game. I’d like to reserve the full details of Sierra’s dramatically changed production methodology for another article, where I can give them their proper due. Suffice for today to say that, while necessary in many respects for a VGA game, the new processes struck everyone as a strange way to create a game using the sharply limited EGA color palette. By far the most obvious difference they made was that everything seemed to take much longer. Lori Ann Cole:

We got the worst of both worlds. We got a new [development] system that had never been tried before, and all the bugs that went with that. And we were doing it under the old-school technology where the colors weren’t as good and all that. We were under a new administration with a different way of treating people. We got time clocks; we had to punch in a number to get into the office so that we would work the set number of hours. We had all of a sudden gone from this free-form company to an authoritarian one: “This is the hours you have to work. Programmers will work over here and artists will work over there, and only their bosses can talk to one another; you can’t talk to the artist that’s doing the art.”

Some of the Coles’ frustrations with the new regime came out in the game they were making. Have a close look at the name of Raseir, an oppressed city — sort of an Arabian Nights version of Nineteen Eighty-Four — where the climax of the game occurs.

Scheduled for a late September release, exactly one year after the release of the first Hero’s Quest, the second game shipped two months behind schedule, coming out far too close to Christmas to have a prayer of fully capitalizing on the holiday rush. And then when it did finally ship, it didn’t even ship as Hero’s Quest II.

In 1989, the same year that Sierra had released the first Hero’s Quest, the British division of the multi-national toys and games giant Milton Bradley had released HeroQuest, a sort of board-gameified version of Dungeons & Dragons. They managed to register their trademark on the name for Europe shortly before Sierra registered theirs for Europe and North America. After the board game turned into a big European success, Milton Bradley elected to bring it to North America the following year, whilst also entering into talks with some British developers about turning it into a computer game. Clearly something had to be done about the name conflict, and thanks to their having registered the trademark first Milton Bradley believed they had the upper hand. When the bigger company’s lawyers came calling, Sierra, unwilling to get entangled in an expensive lawsuit they probably couldn’t win anyway, signed a settlement that not only demanded they change the name of their series but also stated that they couldn’t even continue using the old name long enough to properly advertise that “Hero’s Quest has a new name!” Thus when Hero’s Quest and its nearly finished sequel were hastily rechristened Quest for Glory, the event was announced only via a single four-sentence press release.

So, a veritable perfect storm of circumstances had conspired to undermine the commercial prospects of the newly rechristened Quest for Glory II: Trial by Fire. Sierra’s last parser-driven 16-color game, it was going head to head with the technological wonder that was King’s Quest V — another fantasy game to boot. Due to its late release, it lost the chance to pick up even many or most of the scraps King’s Quest V might have left it. And finally, the name change meant that the very idea of a Quest for Glory II struck most Sierra fans as a complete non sequitur; they had no idea what game it was allegedly a sequel to. Under the circumstances, it’s remarkable that Quest for Glory II performed as well as it did. It sold an estimated 110,000 to 120,000 copies — not quite the hit its predecessor had been, but not quite the flop one could so easily imagine the newer game becoming under the circumstances either. Sales were still strong enough that this eminently worthy series was allowed to continue.

As a finished game, Quest for Glory II betrays relatively little sign of its difficult gestation, even if there are perhaps just a few more rough edges in comparison to its predecessor. The most common complaint is that the much more intricate and linear plot this time out can lead to a fair amount of time spent waiting for the next plot event to fire, with few concrete goals to achieve in the meantime. This syndrome can especially afflict those players who’ve elected to transfer in an established character from the first game, and thus have little need for the grinding with which newbies are likely to occupy themselves. At the same time, though, the new emphasis on plot isn’t entirely unwelcome in light of the almost complete lack of same in the first game, while the setting this time out of a desert land drawn from the Arabian Nights is even more interesting than was that of the previous game. The leisurely pace can make Quest for Glory II feel like a sort of vacation simulator, a relaxing computerized holiday spent chatting with the locals, sampling the cuisine, enjoying belly dances and poetry readings, and shopping in the bazaars. (Indeed, your first challenge in the game is one all too familiar to every tourist in a new land: converting the money you brought with you from Spielburg into the local currency.) I’ve actually heard Quest for Glory II described by a fair number of players as their favorite in the entire series. If push comes to shove, I’d probably have to say that I slightly prefer the first game, but I wouldn’t want to be without either of them. Certainly Quest for Glory II is about as fine a swan song for the era of parser-driven Sierra graphical adventures as one could possibly hope for.

The combat system used in the Quest for Glory games would change constantly from game to game. The one found in the second game is a little more responsive and playable than its predecessor.

Had more adventure-game designers at Sierra and elsewhere followed the Coles’ lead, the history of the genre might have been played out quite differently. As it is, though, we’ll have to be content with the games we do have. I’d hugely encourage any of you who haven’t played the Quest for Glory games to give them a shot — preferably in order, transferring the same character from game to game, just as the Coles ideally intended it. Thanks to our friends at GOG.com, they’re available for purchase today in a painless one-click install for modern systems. They remain as funny, likable, and, yes, generous as ever.

We’ll be returning to the Coles in due course to tell the rest of their series’s story. Next time, though, we’ll turn our attention to the Apple Macintosh, a platform we’ve been neglecting a bit of late, to see how it was faring as the 1990s were fast approaching.

(Sources: Questbusters of December 1989; Computer Gaming World of September 1990 and April 1991; Sierra’s newsletters dated Autumn 1989, Spring 1990, Summer 1991, Spring 1992, and Autumn 1992; Antic of August 1986; STart of Summer 1986; Dragon of October 1991; press releases and annual reports found in the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play. Online sources include Matt Chats 173 and 174; Lori Ann Cole’s interview with Adventure Classic Gaming; Lori and Corey’s appearance on the Space Venture podcast; and various entries on the Coles’ own blog. But my biggest resource at all has been the Coles themselves, who took the time to patiently answer my many nit-picky questions at length. Thank you, Corey and Lori! And finally, courtesy of Corey and Lori, a little bonus for the truly dedicated among you who have read this far: some pages from an issue of their newsletter The Spell Book, including Corey’s take on “Fantasy Gaming Via Computer” circa summer 1982.)