William Gibson was born on March 17, 1948, on the coast of South Carolina. An only child, he was just six years old when his father, a middle manager for a construction company, choked on his food and died while away on one of his many business trips. Mother and son moved back to the former’s childhood home, a small town in Virginia.

Life there was trying for the young boy. His mother, whom he describes today as “chronically anxious and depressive,” never quite seemed to get over the death of her husband, and never quite knew how to relate to her son. Gibson grew up “introverted” and “hyper-bookish,” “the original can’t-hit-the-baseball kid,” feeling perpetually isolated from the world around him. He found refuge, like so many similar personalities, in the shinier, simpler worlds of science fiction. He dreamed of growing up to inhabit those worlds full-time by becoming a science-fiction writer in his own right.

At age 15, desperate for a new start, Gibson convinced his mother to ship him off to a private school for boys in Arizona. It was by his account as bizarre a place as any of the environments that would later show up in his fiction.

It was like a dumping ground for chronically damaged adolescent boys. There were just some weird stories there, from all over the country. They ranged from a 17-year-old, I think from Louisiana, who was like a total alcoholic, man, a terminal, end-of-the-stage guy who weighed about 300 pounds and could drink two quarts of vodka straight up and pretend he hadn’t drunk any to this incredibly great-looking, I mean, beautiful kid from San Francisco, who was crazy because from age 10 his parents had sent him to plastic surgeons because they didn’t like the way he looked.

Still, the clean desert air and the forced socialization of life at the school seemed to do him good. He began to come out of his shell. Meanwhile the 1960s were starting to roll, and young William, again like so many of his peers, replaced science fiction with Beatles, Beats, and, most of all, William S. Burroughs, the writer who remains his personal literary hero to this day.

As his senior year at the boys’ school was just beginning, Gibson’s mother died as abruptly as had his father. Left all alone in the world, he went a little crazy. He was implicated in a drug ring at his school — he still insists today that he was innocent — and kicked out just weeks away from graduation. With no one left to go home to, he hit the road like Burroughs and his other Beat heroes, hoping to discover enlightenment through hedonism; when required like all 18-year-olds to register for the draft, he listed as his primary ambition in life the sampling of every drug ever invented. He apparently made a pretty good stab at realizing that ambition, whilst tramping around North America and, a little later, Europe for years on end, working odd jobs in communes and head shops and taking each day as it came. By necessity, he learned the unwritten rules and hierarchies of power that govern life on the street, a hard-won wisdom that would later set him apart as a writer.

In 1972, he wound up married to a girl he’d met on his travels and living in Vancouver, British Columbia, where he still makes his home to this day. As determined as ever to avoid a conventional workaday life, he realized that, thanks to Canada’s generous student-aid program, he could actually earn more money by attending university than he could working some menial job. He therefore enrolled at the University of British Columbia as an English major. Much to his own surprise, the classes he took there and the people he met in them reawakened his childhood love of science fiction and the written word in general, and with them his desire to write. Gibson’s first short story was published in 1977 in a short-lived, obscure little journal occupying some uncertain ground between fanzine and professional magazine; he earned all of $27 from the venture. Juvenilia though it may be, “Fragments of a Hologram Rose,” a moody, plot-less bit of atmospherics about a jilted lover of the near future who relies on virtual-reality “ASP cassettes” to sleep, already bears his unique stylistic stamp. But after writing it he published nothing else for a long while, occupying himself instead with raising his first child and living the life of a househusband while his wife, now a teacher with a Master’s Degree in linguistics, supported the family. It seemed a writer needed to know so much, and he hardly knew where to start learning it all.

It was punk rock and its child post-punk that finally got him going in earnest. Bands like Wire and Joy Division, who proved you didn’t need to know how to play like Emerson, Lake, and Palmer to make daring, inspiring music, convinced him to apply the same lesson to his writing — to just get on with it. When he did, things happened with stunning quickness. His second story, a delightful romp called “The Gernsback Continuum,” was purchased by Terry Carr, a legendary science-fiction editor and taste-maker, for the 1981 edition of his long-running Universe series of paperback short-story anthologies. With that feather in his cap, Gibson began regularly selling stories to Omni, one of the most respected of the contemporary science-fiction magazines. The first story of his that Omni published, “Johnny Mnemonic,” became the manifesto of a whole new science-fiction sub-genre that had Gibson as its leading light. The small network of writers, critics, and fellow travelers sometimes called themselves “The Movement,” sometimes “The Mirrorshades Group.” But in the end, the world would come to know them as the cyberpunks.

If forced to name one thing that made cyberpunk different from what had come before, I wouldn’t point to any of the exotic computer technology or the murky noirish aesthetics. I’d rather point to eight words found in Gibson’s 1982 story “Burning Chrome”: “the street finds its own use for things.” Those words signaled a shift away from past science fiction’s antiseptic idealized futures toward more organic futures extrapolated from the dirty chaos of the contemporary street. William Gibson, a man who out of necessity had learned to read the street, was the ideal writer to become the movement’s standard bearer. While traditional science-fiction writers were interested in technology for its own sake, Gibson was interested in the effect of technology on people and societies.

Cyberpunk, this first science fiction of the street, was responding to a fundamental shift in the focus of technological development in the real world. The cutting-edge technology of previous decades had been deployed as large-scale, outwardly focused projects, often funded with public money: projects like the Hoover Dam, the Manhattan Project, and that ultimate expression of macro-technology the Apollo moon landing. Even our computers were things filling entire floors, to be programmed and maintained by a small army of lab-coated drones. Golden-age science fiction was right on-board with this emphasis on ever greater scope and scale, extrapolating grand voyages to the stars alongside huge infrastructure projects back home.

Not long after macro-technology enjoyed its greatest hurrah in the communal adventure that was Apollo, however, technology began to get personal. In the mid-1970s, the first personal computers began to appear. In 1979, in an event of almost equal significance, Sony introduced the Walkman, a cassette player the size of your hand, the first piece of lifestyle technology that you could carry around with you. The PC and the Walkman begat our iPhones and Fitbits of today. And if we believe what Gibson and the other cyberpunks were already saying in the early 1980s, those gadgets will in turn beget chip implants, nerve splices, body modifications, and artificial organs. The public has become personal; the outward-facing has become inward-facing; the macro spaces have become micro spaces. We now focus on making ever smaller gadgets, even as we’ve turned our attention away from the outer space beyond our planet in favor of drilling down ever further into the infinitesimal inner spaces of genes and cells, into the tiniest particles that form our universe. All of these trends first showed up in science fiction in the form of cyberpunk.

In marked contrast to the boldness of his stories’ content, Gibson was peculiarly cautious, even hesitant, when it came to the process of writing and of making a proper career out of the act. The fact that Neuromancer, Gibson’s seminal first novel, came into being when it did was entirely down to the intervention of Terry Carr, the same man who had kick-started Gibson’s career as a writer of short stories by publishing “The Gernsback Continuum.” When in 1983 he was put in charge of a new “Ace Specials” line of science-fiction paperbacks reserved exclusively for the first novels of up-and-coming writers, Carr immediately thought again of William Gibson. A great believer in Gibson’s talent and potential importance, he cajoled him into taking an advance and agreeing to write a novel; Gibson had considered himself still “four or five years away” from being ready to tackle such a daunting task. “It wasn’t that vast forces were silently urging me to write,” he says. “It’s just that Terry Carr had given me this money and I had to make up some kind of story. I didn’t have a clue, so I said, ‘Well, I’ll plagiarize myself and see what comes of it.'” And indeed, there isn’t that much in 1984’s Neuromancer that would have felt really new to anyone who had read all of the stories Gibson had written in the few years before it. As a distillation of all the ideas with which he’d been experimenting in one 271-page novel, however, it was hard to beat.

The plot is never the most important aspect of a William Gibson novel, and this first one is no exception to that rule. Still, for the record…

Neuromancer takes place at some indeterminate time in the future, in a gritty society where the planet is polluted and capitalism has run amok, but the designer drugs and technological toys are great if you can pay for them. Our hero is Case, a former “console cowboy” who used to make his living inside the virtual reality, or “Matrix,” of a worldwide computer network, battling “ICE” (“Intrusion Countermeasures Electronics”) and pulling off heists for fun and profit. Unfortunately for him, an ex-employer with a grudge has recently fried those pieces of Case’s brain that interface with his console and let him inject himself into “cyberspace.” Left stuck permanently in “meat” space, as the novel opens he’s a borderline suicidal, down-and-out junkie. But soon he’s offered the chance to get his nervous system repaired and get back into the game by a mysterious fellow named Armitage, mastermind of a ragtag gang of outlaws who are investigating mysterious happenings on the Matrix. Eventually they’ll discover a rogue artificial intelligence behind it all — the titular Neuromancer.

Given that plot summary, we can no longer avoid addressing the thing for which William Gibson will always first and foremost be known, whatever his own wishes on the matter: he’s the man who invented the term “cyberspace,” as well as the verb “to surf” it and with them much of the attitudinal vector that accompanied the rise of the World Wide Web in the 1990s. It should be noted that both neologisms actually predate Neuromancer in Gibson’s work, dating back to 1982’s “Burning Chrome.” And it should most definitely be noted that he was hardly the first to stumble upon many of the ideas behind the attitude. We’ve already chronicled some of the developments in the realms of theory and practical experimentation that led to the World Wide Web. And in the realm of fiction, a mathematician and part-time science-fiction writer named Vernor Vinge had published True Names, a novella describing a worldwide networked virtual reality of its own, in 1981; its plot also bears some striking similarities to that of Gibson’s later Neuromancer. But Vinge was (and is) a much more prosaic writer than Gibson, hewing more to science fiction’s sturdy old school of Asimov, Clarke, and Heinlein. He could propose the idea of a worldwide network and then proceed to work it out with much more technical rigorousness than Gibson could ever dream of mustering, but he couldn’t hope to make it anywhere near as sexy.

For many the most inexplicable thing about Gibson’s work is that he should ever have come up with all this cyberspace stuff in the first place. As he took a certain perverse delight in explaining to his wide-eyed early interviewers, in his real-world life Gibson was something of a Luddite even by the standards of the 1980s. He had, for instance, never owned or used a computer at the time he wrote his early stories and Neuromancer; he wrote of his sleek high-tech futures on a clunky mechanical typewriter dating from 1927. (Gibson immortalized it within Neuromancer itself by placing it in disassembled form on the desk of Julius Deane, an underworld kingpin Case visits early in the novel.) And I’ve seen no evidence that Gibson was aware of True Names prior to writing “Burning Chrome” and Neuromancer, much less the body of esoteric and (at the time) obscure academic literature on computer networking and hypertext.

Typically, Gibson first conceived the idea of the Matrix not from reading tech magazines and academic journals, as Vinge did in conceiving his own so-called “Other Plane,” but on the street, while gazing through the window of an arcade. Seeing the rapt stares of the players made him think they believed in “some kind of actual space behind the screen, someplace you can’t see but you know is there.” In Neuromancer, he describes the Matrix as the rush of a drug high, a sensation with which his youthful adventures in the counterculture had doubtless left him intimately familiar.

He closed his eyes.

Found the ridged face of the power stud.

And in the bloodlit dark behind his eyes, silver phosphenes boiling in from the edge of space, hypnagogic images jerking past like film compiled from random frames. Symbols, figures, faces, a blurred, fragmented mandala of visual information.

Please, he prayed, _now –_

A gray disk, the color of Chiba sky.

_Now –_

Disk beginning to rotate, faster, becoming a sphere of paler gray. Expanding —

And flowed, flowered for him, fluid neon origami trick, the unfolding of his distanceless home, his country, transparent 3D chessboard extending to infinity. Inner eye opening to the stepped scarlet pyramid of the Eastern Seaboard Fission Authority burning beyond the green cubes of Mitsubishi Bank of America, and high and very far away he saw the spiral arms of military systems, forever beyond his reach.

And somewhere he was laughing, in a white-painted loft, distant fingers caressing the deck, tears of release streaking his face.

Much of the supposedly “futuristic” slang in Neuromancer is really “dope dealer’s slang” or “biker’s talk” Gibson had picked up on his travels. Aside from the pervasive role played by the street, he has always listed the most direct influences on Neuromancer as the cut-up novels of his literary hero William S. Burroughs, the noirish detective novels of Dashiell Hammett, and the deliciously dystopian nighttime neon metropolis of Ridley Scott’s film Blade Runner, which in its exploration of subjectivity, the nature of identity, and the influence of technology on same hit many of the same notes that became staples of Gibson’s work. That so much of the modern world seems to be shaped in Neuromancer‘s image says much about Gibson’s purely intuitive but nevertheless prescient genius — and also something about the way that science fiction can be not only a predictor but a shaper of the future, an idea I’ll return to shortly.

But before we move on to that subject and others we should take just a moment more to consider how unique Neuromancer, a bestseller that’s a triumph of style as much as anything else, really is in the annals of science fiction. In a genre still not overly known for striking or elegant prose, William Gibson is one of the few writers immediately recognizable after just a paragraph or two. If, on the other hand, you’re looking for air-tight world-building and careful plotting, Gibson is definitely not the place to find it. “You’ll notice in Neuromancer there’s obviously been a war,” he said in an interview, “but I don’t explain what caused it or even who was fighting it. I’ve never had the patience or the desire to work out the details of who’s doing what to whom, or exactly when something is taking place, or what’s become of the United States.”

I remember standing in a record store one day with a friend of mine who was quite a good guitar player when Jimi Hendrix’s famous Woodstock rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” came over the sound system. “All he does is make a bunch of noise to cover it up every time he flubs a note,” said my friend — albeit, as even he had to agree, kind of a dazzling noise. I sometimes think of that conversation when I read Neuromancer and Gibson’s other early works. There’s an ostentatious, look-at-me! quality to his prose, fueled by, as Gibson admitted, his “blind animal panic” at the prospect of “losing the reader’s attention.” Or, as critic Andrew M. Butler puts it more dryly: “This novel demonstrates great linguistic density, Gibson’s style perhaps blinding the reader to any shortcomings of the novel, and at times distancing us from the characters and what Gibson the author may feel about them.” The actual action of the story, meanwhile, Butler sums up not entirely unfairly as, “Case, the hapless protagonist, stumbles between crises, barely knowing what’s going on, at risk from a femme fatale and being made offers he cannot refuse from mysterious Mr. Bigs.” Again, you don’t read William Gibson for the plot.

Which of course only makes Neuromancer‘s warm reception by the normally plot-focused readers of science fiction all the more striking. But make no mistake: it was a massive critical and commercial success, winning the Hugo and Nebula Awards for its year and, as soon as word spread following its very low-key release, selling like crazy. Unanimously recognized as the science-fiction novel of 1984, it was being labeled the novel of the decade well before the 1980s were actually over; it was just that hard to imagine another book coming out that could compete with its influence. Gibson found himself in a situation somewhat akin to that of Douglas Adams during the same period, lauded by the science-fiction community but never quite feeling a part of it. “Everyone’s been so nice,” he said in the first blush of his success, “but I still feel very much out of place in the company of most science-fiction writers. It’s as though I don’t know what to do when I’m around them, so I’m usually very polite and keep my tie on. Science-fiction authors are often strange, ill-socialized people who have good minds but are still kids.” Politeness or no, descriptions like that weren’t likely to win him many new friends among them. And, indeed, there was a considerable backlash against him by more traditionalist writers and readers, couched in much the same rhetoric that had been deployed against science fiction’s New Wave of writers of twenty years before.

But if we wish to find reasons that so much of science-fiction fandom did embrace Neuromancer so enthusiastically, we can certainly find some that were very practical if not self-serving, and that had little to do with the literary stylings of William S. Burroughs or extrapolations on the social import of technological development. Simply put, Neuromancer was cool, and cool was something that many of the kids who read it decidedly lacked in their own lives. It’s no great revelation to say that kids who like science fiction were and are drawn in disproportionate numbers to computers. Prior to Neuromancer, such kids had few media heroes to look up to; computer hackers were almost uniformly depicted as socially inept nerds in Coke-bottle glasses and pocket protectors. But now along came Case, and with him a new model of the hacker as rock star, dazzling with his Mad Skillz on the Matrix by day and getting hot and heavy with his girlfriend Molly Millions, who seemed to have walked into the book out of an MTV music video, by night. For the young pirates and phreakers who made up the Scene, Neuromancer was the feast they’d never realized they were hungry for. Cyberpunk ideas, iconography, and vocabulary were quickly woven into the Scene’s social fabric.

Like much about Neuromancer‘s success, this way of reading it, which reduced it down to a stylish exercise in escapism, bothered Gibson. His book was, he insisted, not about how cool it was to be “hard and glossy” like Case and Molly, but about “what being hard and glossy does to you.” “My publishers keep telling me the adolescent market is where it’s at,” he said, “and that makes me pretty uncomfortable because I remember what my tastes ran to at that age.”

While Gibson may have been uncomfortable with the huge appetite for comic-book-style cyberpunk that followed Neuromancer‘s success, plenty of others weren’t reluctant to forgo any deeper literary aspirations in favor of piling the casual violence and casual sex atop the casual tech. As the violence got ever more extreme and the sex ever more lurid, cyberpunk risked turning into the most insufferable of clichés.

Sensation though cyberpunk was in the rather insular world of written science fiction, William Gibson and the sub-genre he had pioneered filtered only gradually into the world outside of that ghetto. The first cyberpunk character to take to the screen arguably was, in what feels a very appropriate gesture, a character who allegedly lived within a television: Max Headroom, a curious computerized talking head who became an odd sort of cultural icon for a few years there during the mid- to late-1980s. Invented for a 1985 low-budget British television movie called Max Headroom: 20 Minutes into the Future, Max went on to host his own talk show on British television, to become an international spokesman for the ill-fated New Coke, and finally to star in an American dramatic series which managed to air 14 episodes on ABC during 1987 and 1988. While they lacked anything precisely equivalent to the Matrix, the movie and the dramatic series otherwise trafficked in themes, dystopic environments, and gritty technologies of the street not far removed at all from those of Neuromancer. The ambitions of Max’s creators were constantly curtailed by painfully obvious budgetary limitations as well as the pop-cultural baggage carried by the character himself; by the time of the 1987 television series he had become more associated with camp than serious science fiction. Nevertheless, the television series in particular makes for fascinating viewing for any student of cyberpunk history. (The series endeared itself to Commodore Amiga owners in another way: Amigas were used to create many of the visual effects used on the show, although not, as was occasionally reported, to render Max Headroom himself. He was actually played by an actor wearing a prosthetic mask, with various visual and auditory effects added in post-production to create the character’s trademark tics.)

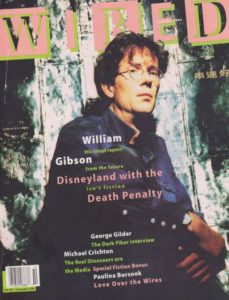

There are other examples of cyberpunk’s slowly growing influence to be found in the film and television of the late 1980s and early 1990s, such as the street-savvy, darkly humorous low-budget action flick Robocop. But William Gibson’s elevation to the status of Prophet of Cyberspace in the eyes of the mainstream really began in earnest with a magazine called Wired, launched in 1993 by an eclectic mix of journalists, entrepreneurs, and academics. Envisioned as a glossy lifestyle magazine for the hip and tech-conscious — the initial pitch labeled it “the Rolling Stone of technology” — Wired‘s aesthetics were to a large degree modeled on William Gibson. When they convinced him to contribute a rare non-fiction article (on Singapore, which he described as “Disneyland with the death penalty”) to the fourth issue, the editors were so excited that they stuck the author rather than the subject of the article on their magazine’s cover.

Well-funded and editorially polished in all the ways that traditional technology journals weren’t, Wired was perfectly situated to become mainstream journalism’s go-to resource for understanding the World Wide Web and the technology bubble expanding around it. It was largely through Wired that “cyberspace” and “surfing” became indelible parts of the vocabulary of the age, even as both neologisms felt a long, long way in spirit from the actual experience of using the World Wide Web in those early days, involving as it did mostly text-only pages delivered to the screen at a glacial pace. No matter. The vocabulary surrounding technology has always tended to be grounded in aspiration rather than reality, and perhaps that’s as it should be. By the latter 1990s, Gibson was being acknowledged by even such dowdy organs as The New York Times as the man who had predicted it all five years before the World Wide Web was so much as a gleam in the eye of Tim Berners-Lee.

To ask whether William Gibson deserves his popular status as a prophet is, I would suggest, a little pointless. Yes, Vernor Vinge may have better claim to the title in the realm of fiction, and certainly people like Vannevar Bush, Douglas Engelbart, Ted Nelson, and even Bill Atkinson of Apple have huge claims on the raw ideas that turned into the World Wide Web. Even within the oeuvre of William Gibson himself, his predictions in other areas of personal technology and society — not least his anticipation of globalization and its discontents — strike me as actually more prescient than his rather vague vision of a global computerized Matrix.

Yet, whether we like it or not, journalism and popular history do tend to condense complexities down to single, easily graspable names, and in this case the beneficiary of that tendency is William Gibson. And it’s not as if he didn’t make a contribution. Whatever the rest did, Gibson was the guy who made the idea of a networked society — almost a networked consciousness — accessible, cool, and fun. In doing so, he turned the old idea of science fiction as prophecy on its head. Those kids who grew up reading Neuromancer became the adults who are building the technology of today. If, with the latest developments in virtual reality, we seem to be inching ever closer to a true worldwide Matrix, we can well ask ourselves who is the influenced and who is the influencer. Certainly Neuromancer‘s effect on our popular culture has been all but incalculable. The Matrix, the fifth highest-grossing film of 1999 and a mind-expanding pop-culture touchstone of its era, borrowed from Gibson to the extent of naming itself after his version of virtual reality. In our own time, it’s hard to imagine current too-cool-for-school television hits like Westworld, Mr. Robot, and Black Mirror existing without the example of Neuromancer (or, at least, without The Matrix and thus by extension Neuromancer). The old stereotype of the closeted computer nerd, if not quite banished to the closet from which it came, does now face strong competition indeed. Cyberpunk has largely faded away as a science-fiction sub-genre or even just a recognized point of view, not because the ideas behind it died but because they’ve become so darn commonplace.

You may have noticed that up to this point I’ve said nothing about the books William Gibson wrote after Neuromancer. That it’s been so easy to avoid doing so says much about his subsequent career, doomed as it is always to be overshadowed by his very first novel. For understandable reasons, the situation hasn’t always sat well with Gibson himself. Already in 1992, he could only wryly reply, “Yeah, and they’ll never let me forget it,” when introduced as the man who invented cyberspace — this well before his mainstream fame as the inventor of the word had really even begun to take off. Writing a first book with the impact of Neuromancer is not an unalloyed blessing.

That said, one must also acknowledge that Gibson didn’t do his later career any favors in getting out from under Neuromancer‘s shadow. Evincing that peculiar professional caution that always sat behind his bold prose, he mined the same territory for years, releasing a series of books whose titles — Count Zero, Mona Lisa Overdrive, Virtual Light — seem as of a piece as their dystopic settings and their vaguely realized plots. It’s not that these books have nothing to say; it’s rather that almost everything they do say is already said by Neuromancer. His one major pre-millennial departure from form, 1990’s The Difference Engine, is an influential exercise in Victorian steampunk, but also a book whose genesis owed much to his good friend and fellow cyberpunk icon Bruce Sterling, with whom he collaborated on it.

Here’s the thing, though: as he wrote all those somewhat interchangeable novels through the late 1980s and 1990s, William Gibson was becoming a better writer. His big breakthrough came with 2003’s Pattern Recognition, in my opinion the best pure novel he’s ever written. Perhaps not coincidentally, Pattern Recognition also marks the moment when Gibson, who had been steadily inching closer to the present ever since Neuromancer, finally decided to set a story in our own contemporary world. His prose is as wonderful as ever, full of sentence after sentence I can only wish I’d come up with, yet now free of the look-at-me! ostentation of his early work. One of the best ways to appreciate how much subtler a writer Gibson has become is to look at his handling of his female characters. Molly Millions from Neuromancer was every teenage boy’s wet dream come to life. Cayce, the protagonist of Pattern Recognition — her name is a sly nod back to Neuromancer‘s Case — is, well, just a person. Her sexuality is part of her identity, but it’s just a part. A strong, capable, intelligent character, she’s not celebrated by the author for any of these qualities. Instead she’s allowed just to be. This strikes me as a wonderful sign of progress — for William Gibson, and perhaps for all of us.

Which isn’t to say that Gibson’s dystopias have turned into utopias. While his actual plots remain as underwhelming as ever, no working writer of today that I’m aware of captures so adroitly the sense of dislocation and isolation that has become such a staple of post-millennial life — paradoxically so in this world that’s more interconnected than ever. If some person from the future or the past asked you how we live now, you could do a lot worse than to simply hand her one of William Gibson’s recent novels.

Whether Gibson is still a science-fiction writer is up for debate and, like so many exercises in labeling, ultimately inconsequential. There remains a coterie of old fans unhappy with the new direction, who complain about every new novel he writes because it isn’t another Neuromancer. By way of compensation, Gibson has come to be widely accepted as a writer of note outside of science-fiction fandom — a writer of note, that is, for something more than being the inventor of cyberspace. That of course doesn’t mean he will ever write another book with the impact of Neuromancer, but Gibson, who never envisioned himself as anything more than a cult writer in the first place, seems to have made his peace at last with the inevitability of the phrases “author of Neuromancer” and “coiner of the term ‘cyberspace'” appearing in the first line of his eventual obituary. Asked in 2007 by The New York Times whether he was “sick of being known as the writer who coined the word ‘cyberspace,'” he said he thought he’d “miss it if it went away.” In the meantime, he has more novels to write. We may not be able to escape our yesterdays, but we always have our today.

(Sources: True Names by Vernor Vinge; Conversations with William Gibson, edited by Patrick A. Smith; Bruce Sterling and William Gibson’s introductions to the William Gibson short-story collection Burning Chrome; Bruce Sterling’s preface to the cyberpunk short-story anthology Mirrorshades; “Science Fiction from 1980 to the Present” by John Clute and “Postmodernism and Science Fiction” by Andrew M. Butler, both found in The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction; Spin of April 1987; Los Angeles Times of September 12 1993; The New York Times of August 19 2007; William Gibson’s autobiography from his website; “William Gibson and the Summer of Love” from the Toronto Dream Project; and of course the short stories and novels of William Gibson.)