For text-adventure fans confronting the emerging reality of a post-Infocom world, AGT was a godsend, allowing amateurs for the first time to create games that at a quick glance might appear to match those of Infocom. Still, AGT was far from the answer to every prayer, for the fact remained that it would have to be a very quick glance indeed. David Malmberg, the developer of AGT, was ingenious and motivated, but he was also a self-taught programmer with little background in the complexities of programming languages and compiler design. He had built AGT by adding to Mark Welch’s profoundly limited GAGS system for creating generic database-driven text adventures a scripting language that ignored pretty much all of the precepts of good language design. What he had ended up with was almost a sort of technological folk art, clever and creative and practical in its way, but rather horrifying to anyone with a deeper grounding in computing theory. The best argument in favor of AGT was that it worked — basically. While the system was undoubtedly more capable than anything that had been available to hobbyists before, it still didn’t take much poking at an AGT game before the rickety edifice’s seams began to show. A number of authors would push the system to unforeseen heights, in the process creating a number of classic games, but it was obvious that AGT could never work quite well enough to create games as polished as those of Infocom. To do that, a language would be needed that was truly designed rather than improvised. Enter Michael J. Roberts with his Text Adventure Development System, or TADS.

Roberts had first started programming on his school’s DEC PDP-11 system in the 1970s at the age of 12, and thereafter had ridden the first wave of the PC revolution. In those early days, text adventures were among the most popular games there were. Like so many of his peers, Roberts studied the BASIC listings published in books and magazines carefully, and soon started trying to write adventures of his own. And like so many of those among his peers who became really serious about the business, he soon realized that each game he wrote was similar enough to each other game that it made little sense to continually reinvent the wheel by writing every one from scratch. Roberts:

It occurred to me that lots of the code could be generalized to any adventure game. So, I tried to write a little library of common functions — the functions operated on a set of data files that specified the vocabulary words, room descriptions, and so on.

This was a nice approach in some ways; the idea was that the game would be described entirely with these data files. The problem that I kept running into was that I’d have to write special-purpose functions for certain rooms, or certain commands — you couldn’t write an entire game with just the data files, because you always had to customize the library functions for each game. What I really wanted was a way to put programming commands into the data files themselves, so I didn’t have to modify the library routines.

Once you start putting procedural code into data files, you essentially have a programming language. At first, I tried to avoid the work of writing a real language interpreter by making the language very limited and easy to parse. That was better than just the data files, but it was tedious to write programs in a limited language. I eventually saw that you really needed a good language that was easy to use to be able to write decent games.

Roberts, in other words, was discovering for himself the limitations and inelegancies that were inherent to a system like AGT — the limitations and inelegancies of grafting a scripting language onto a generic database engine.

But it wasn’t until he went off to the California Institute of Technology that his experiments progressed further. Despite his official status as a physics major, Caltech offered plenty of opportunity for a motivated young hacker like him to immerse himself in the latest thinking about programming languages and compiler design. In the air all around him was computer science’s hot new buzzword of “object-oriented” design. By allowing the programmer to gather together data and the code that manipulates that data into semi-autonomous “objects,” an object-oriented programming language was an ideal fit for the problems of constructing a text adventure. (Indeed, it was such an ideal fit that Infocom had developed a heavily object-oriented language of their own in the form of their in-house adventure-programming language ZIL years before the buzzword came to prominence.) Following yet another trend, Roberts based his new adventure language’s syntax largely on that of C, the language that was quickly becoming the lingua franca of the world of computer programming in general.

On the theory that a worked example is worth a thousand abstractions, and following the precedent I set with my article on AGT, I’d like to show you a little bit of TADS code taken from a real game. You may want to refer back to my AGT article to contemplate the comparisons I’m about to make between the two languages. Taken together, the two articles will hopefully lead to a fuller understanding of just how TADS evolved the text-adventure-programming state of the art over AGT.

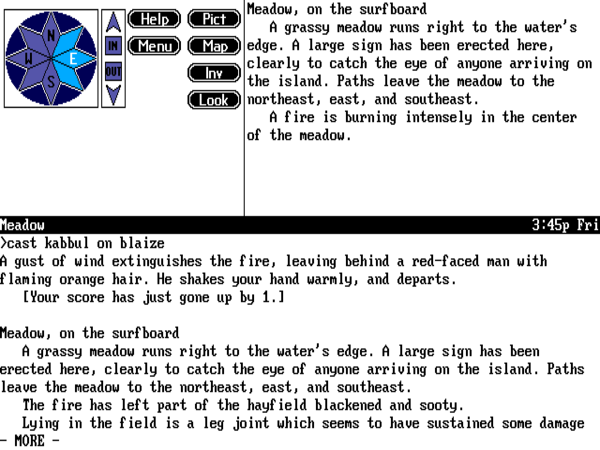

The game we’ll be looking at this time is Ditch Day Drifter, a perfectly playable standalone adventure that was also used by Mike Roberts as his example game for TADS learners. Once again following my AGT precedent, I’ll focus on that most essential piece of equipment for any old-school adventurer: a light source. Here we see Ditch Day Drifter‘s flashlight.

flashlight: container, lightsource

sdesc = "flashlight"

noun = 'flashlight' 'light'

adjective = 'flash'

location = security

ioPutIn( actor, dobj ) =

{

if ( dobj <> battery )

{

"You can't put "; dobj.thedesc; " into the flashlight. ";

}

else pass ioPutIn;

}

Grab( obj ) =

{

/*

* Grab( obj ) is invoked whenever an object 'obj' that was

* previously located within me is removed. If the battery is

* removed, the flashlight turns off.

*/

if ( obj = battery ) self.islit := nil;

}

ldesc =

{

if ( battery.location = self )

{

if ( self.islit )

"The flashlight (which contains a battery) is turned on

and is providing a warm, reassuring beam of light. ";

else

"The flashlight (which contains a battery) is currently off. ";

}

else

{

"The flashlight is off. It seems to be missing a battery. ";

}

}

verDoTurnon( actor ) =

{

if ( self.islit ) "It's already on! ";

}

doTurnon( actor ) =

{

if ( battery.location = self )

{

"The flashlight is now on. ";

self.islit := true;

}

else "The flashlight won't turn on without a battery. ";

}

verDoTurnoff( actor ) =

{

if ( not self.islit ) "It's not on. ";

}

doTurnoff( actor ) =

{

"Okay, the flashlight is now turned off. ";

self.islit := nil;

}

;

Unlike the case of our AGT example, for which we had to pull together several snippets taken from entirely separate files, we have here everything the game needs to know about the flashlight, all in one place thanks to TADS’s object-oriented design. Let’s step through it bit by bit.

The first line tells us that the flashlight is an object which inherits many details from two generic classes of objects included in the standard TADS library: it’s both a container, meaning we can put things in it and remove them, and a light source. The rest of the new object’s definition fleshes out and sometimes overrides the very basic implementations of these two things provided by the TADS library. The few lines after the first will look very familiar to veterans of my AGT article. So, the flashlight has a short description, to be used in inventory listings and so forth, of simply “flashlight.” The parser recognizes it as “flashlight” or “light” or “flash light,” and at the beginning of the game it’s in the room called “security.”

After this point, though, we begin to see the differences between TADS’s object-oriented approach and that of AGT. Remember that adding customized behaviors to AGT’s objects could be accomplished only by checking the player’s typed commands one by one against a long series of conditions. The scripts to do so were entirely divorced from the objects they manipulated, a state of affairs which could only become more and more confusing for the author as a game grew. Like those created using many other self-consciously beginner-friendly programming languages, AGT programs become more and more of a tangle as their authors’ ambitions grow, until one reaches a point where working with the allegedly easy language becomes far more difficult than working with the allegedly difficult one. Contrast this with TADS’s cleaner approach, which, like Infocom’s ZIL, places all the code and data pertaining to the flashlight together in one tidy package.

Continuing to read through the TADS snippet above, we override the generic container’s handling of the player attempting to put something into it, specifying that this particular container can only contain one particular object: the battery. Then we specify that if the player removes the battery from the flashlight when the flashlight is turned on, its status changes to not lit — i.e., it goes out.

Next we have the flashlight’s “long description,” meaning what will happen in response to the player attempting to “examine” it. TADS allows us to insert code here to describe the flashlight differently depending on whether it’s on or off, and, if it’s in the latter state, depending on whether it contains the battery.

Finally, we override the generic light source’s handling of the player turning it on or off, to tie the written description of these actions to the specific case of a flashlight and to reckon with the presence or absence of the battery. Again, note how much cleaner this is than the AGT implementation of the same concepts. In AGT, we were forced to rely on several different versions of the flashlight object, which we swapped in and out of play in response to changes in the conceptual flashlight. In TADS, concept and code can remain one, and the steps necessary to implement even a huge adventure game can continue to be tackled in relative isolation from one another.

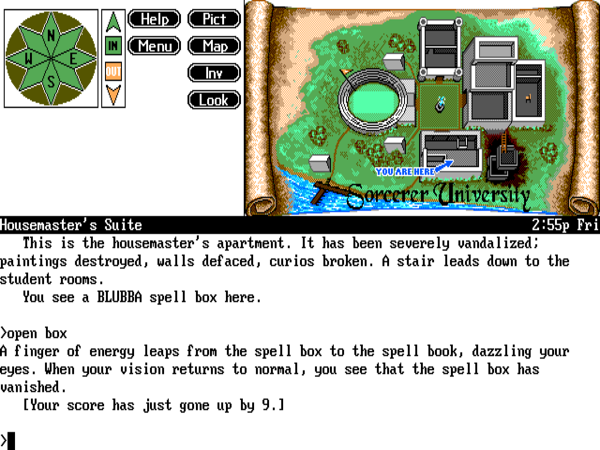

Instructive though it is to compare the divergent approaches of the two systems, it is important to state that TADS wasn’t created in reaction to AGT. Computing communities were much more segregated in those days than they are today, and thus Roberts wasn’t even aware of AGT’s existence when he began developing TADS. Beginning as a language tailored strictly to his own needs as a would-be text-adventure author, it only gradually over the course of the latter 1980s morphed in his mind into something that might be suitable for public consumption. What it morphed into was, nevertheless, something truly remarkable: the first publicly available system that in the hands of a sufficiently motivated author really could create text adventures as sophisticated as those of Infocom. If anything, TADS had the edge on ZIL: its syntax was cleaner, its world model more thorough and consistent, and it ran in a virtual machine of its own that would prove as portable as the Z-Machine but was free of the latter’s brutal size constraints.

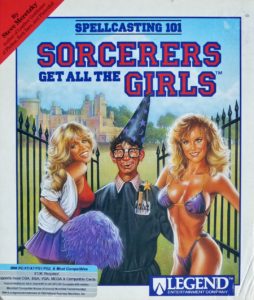

As TADS was rounding into this very impressive state, Roberts set up a company with a friend of his named Steve McAdams. In tribute to Roberts’s degree in physics, they called it High Energy Software, and, following in the footsteps of David Malmberg’s little AGT enterprise, planned to sell TADS as shareware through it. Version 1.0 of TADS was released in September of 1990, alongside two games to show it off. One was the afore-referenced freebie example game Ditch Day Drifter, while the other was Deep Space Drifter, a bigger game released as a shareware product in its own right. Both games tread well-worn pathways in terms of subject matter, the former being yet another “life at my university” scenario, the latter a science-fiction scenario with some of the feel of Infocom’s Starcross. Both games are a little sparse and workmanlike in their writing and construction, and some elements of them, like the 160-room maze in Deep Space Drifter, are hopelessly old school. (It’s not a maze in the conventional drop-and-map sense, and the puzzle behind it is actually very clever, but still… 160 rooms, Mike? Was that really necessary?) On the positive side, however, both games are quite unusual for their era in being scrupulously fair — as long, that is, as you don’t consider the very idea of a huge maze you have to map out for yourself to be a crime against humanity.

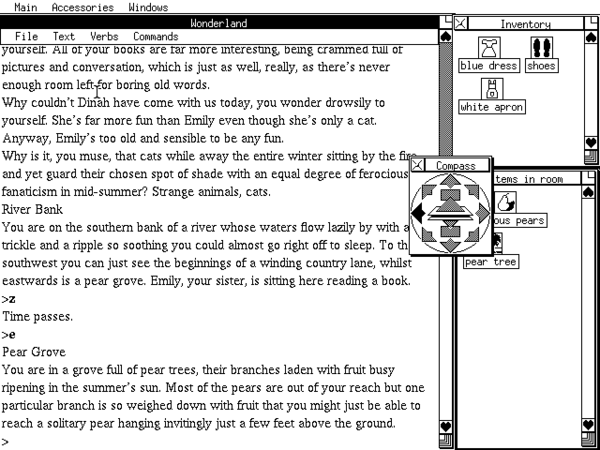

But undoubtedly the most ambitious and, in their way, the most impressive of the early TADS games came not from High Energy Software but rather from a pair of University of Maryland students named David Leary and David Baggett, who started a company they called Adventions to sell TADS text adventures via the shareware model. Of all the folks dabbling in shareware text adventures during the early 1990s, it was Adventions who made the most concerted and sustained effort at building a real business out of it. Their flagship series came to encompass three big unabashed Zork homages — Unnkulian Underworld: The Unknown Unventure, Unnkulian Unventure II: The Secret of Acme, and Unnkulia Zero: The Search for Amanda — alongside Unnkulia One-Half: The Salesman Triumphant, a free snack-sized sampler game.

When the first Unnkulia game was released remarkably quickly on the heels of TADS itself — Mike Roberts can’t recall for sure, but believes Leary and Baggett likely developed it with an early beta copy of the system — it stood as easily the most immediately impressive amateur text adventure ever. The text was polished in a way that few text-adventure developers outside of Infocom, whether amateur or professional, had ever bothered to do, being free of the self-conscious meta-textual asides and atrocious grammar that had always marked the genre. Adventions’s text, by contrast, looked like it had actually been proof-read, and possibly several times at that. Likewise, the game took full advantage of the sophisticated TADS world model to offer puzzles of an intricacy that just wasn’t possible with a tool like AGT. The first Unnkulia game and those which followed were almost in a league of their own for some time in all these respects.

On the other hand, though, the Unnkulia games strike me as curiously unlikable. You can get a good idea of their personality just by looking at their names. If the name Unnkulia — be sure to say it out loud — strikes you as hilarious, congratulations, you may have found your new favorite series. If it instead just strikes you as stupid, as it does me, perhaps not so much. (I admit that my attitude may be affected by having to type the damn thing over and over again; no matter how hard I try, I just can’t seem to remember how to spell it.) Much of the humor inside the games for some reason involves “cheez” — and yes, it’s spelled just like that. The humor has always been, at best, polarizing, and I have no doubt on which side I stand. In addition to just not being all that funny, there’s a certain self-satisfied smugness about the whole enterprise that rubs me the wrong way. At the risk of over-personalizing my reaction to it, I’ll say that it feels like the work of two young men who are nowhere near as witty as they think they are. In short, there’s something about these games that I find insufferable.

In terms of design, the Unnkulia games are an equally odd brew. It’s clear that they’ve been quite rigorously tested — another thing that sets them apart from most text adventures of their era — and they’re free of mazes, guess-the-verb puzzles, and the other most-loathed aspects of their genre. Yet the puzzle design still isn’t all that satisfying. There’s an obsession with hiding objects behind, under, and inside unlikely things — an obsession which is ironically enabled by the TADS world model, which was the first to really allow this sort of thing. Sometimes, including in the very first room of the very first game, you even have to look twice to find everything. Hiding surprises in plain view is okay once or twice, but Baggett and Leary lean on it so hard that it quickly starts to feel lazy. When they do get more ambitious with their puzzles, however, they have a tendency to get too ambitious, losing sight in that peculiar way so many text-adventure authors have of how things actually work in a real physical environment. Let me offer a quick example.

So, let’s set up the situation (spoilers ahoy!). You have a bronze plate, but you need a bronze coin to feed to a vending machine. During your wanderings in search of that among other things, you come upon the room below. (These passages should also convey some more of the, shall we say, unique flavor of the writing and humor.)

Inner Temple of Duhdism

This chamber is the temple of Duhdism, the religion of the ancients. It's rather a letdown, after all Kuulest told you about it. A small altar with a round hole in the center is in the center of the chamber. Carved in stone on the far wall is some writing, the legend of Duhdism. The only exit from this chamber is back to the east. You feel at peace in this room, as if you could sleep here - or maybe you're just kind of bored.

>read writing

"The Legend of Duhdha and the Shot to Heaven:

One fine summer day, Duhdha was loading a catapult with rocks. When his students asked what he was doing, the great Duhdha just smiled and said, "Something real neat." Soon, the catapult was full, and Duhdha pulled the lever as his students looked on. The stones crushed the annoying students, leaving the great man to ponder the nature of mankind. Not only did the rocks eliminate distraction from Duhdha's life, but they fell to the ground in a pattern which has since become a standard opening for the intellectual game of "Went." Since then, the altar at the Temple of Duhdha fires a small stone into the air soon after a worshipper enters, to honor Duhdha - who taught his students not to ask stupid questions and to pretty much just leave him alone."

>x altar

The altar is about two feet by one foot, and about three feet tall. There's a small round hole in the exact center of the top surface. The altar is covered with rock dust. There's nothing else on the Duhdist altar.

>z

Time passes...

A rock shoots into the air from the hole in the altar, shattering on the ceiling and spreading rock dust on the altar. From the outer chamber, you hear the old monk cry "Praise Duhdha!."

We obviously need to do something with this rock-spewing altar, but it’s far from clear what that might be, and fiddling with it in various ways offers no other clues. Putting things on it has no effect on either the thing that’s just been put there or the rocks that keep flying out — except in the case of one thing: the bronze plate we’re carrying around with us.

>put plate on altar

Done.

>z

Time passes...

A rock shoots from the altar at high velocities, puncturing the plate in the center. The rock shatters on the ceiling, spraying rock dust. You hear a tinkling sound as a tiny bronze disc falls on the floor. From the outer chamber, you hear the monk shout "Praise Duhdha!"

*** Your score has just changed. ***

When you reach this solution either by turning to the walkthrough or through sheer dogged persistence — I maintain that no one would ever anticipate this result — you might then begin to wonder what physical laws govern the world of Unnkulia. In the world we live in, there’s no way that the flying rock would punch a perfect hole neatly through the middle of a bronze plate that happened to just be lying on the altar. Without something to hold it in place, the plate would, of course, simply be thrown into the air to come down elsewhere, still intact. The ironic thing is that this puzzle could so easily have been fixed, could have even become a pretty good one, with the addition of a set of grooves or notches of some sort on the altar to hold the plate in place. Somehow this seems emblematic of the Unnkulia series as a whole.

Like everyone else who dreamed of making a living from shareware text adventures, Leary and Baggett found it to be a dispiriting exercise, although one certainly can’t fault them for a lack of persistence. With some bitterness — “It’s disappointing that although there are so many IF enthusiasts out there, so few are willing to pay a fair price for such strong work,” said Baggett — they finally gave up in time to release their final game, 1994’s very interesting The Legend Lives! — more on that in a future article — for free before exiting from the text-adventure scene entirely.

The same dispiriting lack of paying customers largely applied to makers of text-adventure languages as well. Mike Roberts estimates that his rate of TADS registrations peaked “on that same order” as David Malmberg’s pace of 100 AGT registrations per year, or “maybe a little lower. I’d remember if it had been much higher because I’d have been spending all day stuffing envelopes.” Whatever their respective rates of registration, far more AGT than TADS games continued to be released in the early 1990s. While that may have struck some — not least among them Mike Roberts — as disappointing, the reasons behind it aren’t hard to divine. AGT had a head start of several years, it had an annual competition to serve as an incentive for people to finish their games, and, perhaps most of all, it presented a much less daunting prospect for the non-programming beginner. Its kind and gentle manual was superb, and it was possible to get started making simple games using it without doing any programming at all, just by filling in fields representing rooms and objects. TADS, by contrast, offered a manual that was complete but much drier, and was on the whole a much more programmer-oriented experience. The initial learning curve undoubtedly put many people off who, had they persisted, would have found TADS a much better tool for realizing their dreams of adventures in text than AGT.

Some time after the Adventions guys and David Malmberg gave up on their respective shareware products, Roberts and his partner Steve McAdams also decided that they just weren’t making enough money from TADS to bother continuing to sell it. And so they made TADS as well free. And with those decisions, the brief-lived era of shareware interactive fiction passed into history.

But, despite the disappointments, Mike Roberts and TADS weren’t going anywhere. Unlike Leary, Baggett, and Malmberg, he stayed on the scene after giving up on the shareware thing, continuing to support TADS as open-source software. It took its place alongside a newer — and also free — language called Inform as one of the two great technical catalyzers of what some came to call, perhaps a little preciously, the Interactive Fiction Renaissance of the mid- to late-1990s. So, I’ll have much, much more to write about TADS and the games made using it in years to come. One might even say that the system wouldn’t really come into its own as a creative force until Roberts made that important decision to make it free.

Still, the importance of TADS’s arrival in September of 1990 shouldn’t be neglected. Somewhat underutilized though it may initially have been, it nevertheless remained the first development system that was capable of matching Infocom’s best games. If the amateur scene still largely failed to meet that lofty mark, they could no longer blame their technology. On a more personal note, the emergence of Mike Roberts on the scene marks the arrival of the first of the stalwarts who would go on to build the modern interactive-fiction community. We’re still in an era that will strike even most of the most dedicated fans of modern interactive fiction as murky prehistory, but some people and artifacts we recognize are beginning to emerge from the primordial ooze. More than a quarter of a century later, Mike Roberts and TADS are still with us.

(Sources: SynTax issues 17 and 36; SPAG issues 5 and 33; Mike Roberts’s interview for Jason Scott’s Get Lamp documentary, which Jason was kind of enough to share with me in its entirety. And my thanks to Mike Roberts himself, who answered many questions personally via email.

Ditch Day Drifter and Deep Space Drifter are available on the IF Archive for play via a TADS interpreter. The Adventions games are available there as well.)