A major financial panic struck the United States in August of 1857, just as the Niagara was making the first attempt to lay the Atlantic cable. Cyrus Field had to mortgage his existing businesses heavily just to keep them going. But he was buoyed by one thing: as the aftershocks of the panic spread to Europe, packet steamers took to making St. John’s, Newfoundland, their first port of call in the Americas for the express purpose of passing the financial news they carried to the island’s telegraph operators so that it could reach Wall Street as quickly as possible. It had taken the widespread threat of financial ruin, but Frederick Gisborne’s predictions about the usefulness of a Newfoundland telegraph were finally coming true. Now just imagine if the line could be extended all the way across the Atlantic…

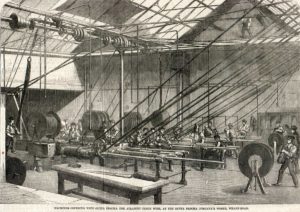

While he waited for the return of good weather to the Atlantic, Field sought remedies for everything that had gone wrong with the first attempt to lay a telegraph cable across an ocean. The Niagara‘s chief engineer, a man named William Everett, had examined Charles Bright’s paying-out mechanism with interest during the last expedition, and come up with a number of suggestions for improving it. Field sought and was granted Everett’s temporary release from the United States Navy, and brought him to London to redesign the machine. The result was actually simpler in most ways, being just one-fourth of the weight and one-third of the size of Bright’s design. But it incorporated a critical new feature: the brake now set and released itself automatically in response to the level of tension on the cable. “It seemed to have the intelligence of a human being, to know when to hold on and when to let go,” writes Henry Field. In reality, it was even better than a human being, in that it never got tired and never let its mind wander; no longer would a moment’s inattention on the part of a fallible human operator be able to wreck the whole project.

Charles Bright accepted the superseding of his original design with good grace; he was an engineer to the core, the new paying-out machine was clearly superior to the old one, and so there wasn’t much to discuss in his view. There was ongoing discord, however, between two more of Cyrus Field’s little band of advisors.

Wildman Whitehouse and William Thomson had been competing for Field’s ear for quite some time now. At first the former had won out, largely because he told Field what he most wished to hear: that a transatlantic telegraph could be made to work with an unusually long but otherwise fairly plebeian cable, using bog-standard sending and receiving mechanisms. But Field was a thoughtful man, and of late he’d begun losing faith in the surgeon and amateur electrical experimenter. He was particularly bothered by Whitehouse’s blasé attitude toward the issue of signal retardation.

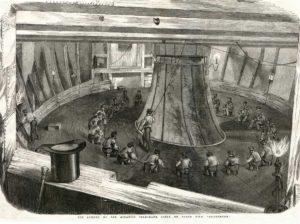

Meanwhile Thomson was continuing to whisper contrary advice in his ear. He said that he still thought it would be best to use a thicker cable like the one he had originally proposed, but, when informed that there just wasn’t money in the budget for such a thing, he said that he thought he could get even Whitehouse’s design to work more efficiently. His scheme exploited the fact that even a heavily retarded signal probably wouldn’t become completely uniform: the current at the far end of the wire would still be full of subtle rises and falls where the formerly discrete dots and dashes of Morse Code had been. Thomson had been working on a new, ultrasensitive galvanometer, which ingeniously employed a lamp, a magnet, and a tiny mirror to detect the slightest variation in current amplitude. Two operators would work together to translate a signal on the receiving end of the cable: one, trained to interpret the telltale patterns of reflected light bobbing up and down in front of him, would translate them into Morse Code and call it out to his partner. Over the strident objections of Whitehouse, Field agreed to install the system, and also agreed to give Thomson access to the enormous spools of existing cable that were now warehoused in Plymouth, England, waiting for the return of spring. Thomson meticulously tested the cable one stretch at a time, and convinced Field to let him cut out those sections where its conductivity was worst.

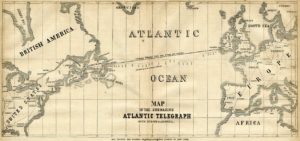

The United States and Royal Navies agreed to lend the Atlantic Telegraph Company the same two vessels as last time for a second attempt at laying the cable. To save time, however, it was decided that the ships would work simultaneously: they would sail to the middle of the Atlantic, splice their cables together there, then each head toward a separate continent. So, in April of 1858, the Niagara and the Agamemnon arrived in Plymouth to begin the six-week process of loading the cable. They sailed together from there on June 10. Samuel Morse elected not to travel with the expedition this time, but Charles Bright, William Thomson, Cyrus Field and his two brothers, and many of the other principals were aboard one or the other ship.

They had been told that “June was the best month for crossing the Atlantic,” as Henry Field writes. They should be “almost sure of fair weather.” On the contrary, on June 13 the little fleet sailed into the teeth of one of the worst Atlantic storms of the nineteenth century. The landlubbers aboard had never imagined that such a natural fury as this could exist. For three days, the ships were lashed relentlessly by the wind and waves. With 1250 tons of cable each on their decks and in their holds, both the Niagara and the Agamemnon rode low in the water and were a handful to steer under the best of circumstances; now they were in acute danger of foundering, capsizing, or simply breaking to pieces under the battering.

The Agamemnon was especially hard-pressed: bracing beams snapped below decks, and the hull sprang leaks in multiple locations. “The ship was almost as wet inside as out,” wrote a horrified Times of London reporter who had joined the expedition. The crew’s greatest fear was that one of the spools of cable in the hold would break loose and punch right through the hull; they fought a never-ending battle to secure the spools against each successive onslaught. While they were thus distracted, the ship’s gigantic coal hampers gave way instead, sending tons of the filthy stuff skittering everywhere, injuring many of the crew. That the Agamemnon survived the storm at all was thanks to masterful seamanship on the part of its captain, who remained awake on the bridge for 72 hours straight, plotting how best to ride out each wave.

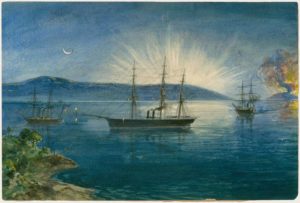

An artist’s rendering of the Agamemnon in the grip of the storm, as published in the Illustrated London News.

Separated from one another by the storm, the two ships met up again on June 25 smack dab in the middle of an Atlantic Ocean that was once again so tranquil as to “seem almost unnatural,” as Henry Field puts it. The men aboard the Niagara were shocked at the state of the Agamemnon; it was so badly battered and so covered in coal dust that it looked more like a garbage scow than a proud Royal Navy ship of the line. But no matter: it was time to begin the task they had come here to carry out.

So, the cables were duly spliced on June 26, and the process of laying them began — with far less ceremony than last time, given that there were no government dignitaries on the scene. The two ships steamed away from one another, the Niagara westward toward Newfoundland, the Agamemnon eastward toward Ireland, with telegraph operators aboard each ship constantly testing the tether that bound them together as they went. They had covered a combined distance of just 40 miles when the line suddenly went dead. Following the agreed-upon protocol in case of such an eventuality, both crews cut their end of the cable, letting it drop uselessly into the ocean, then turned around and steamed back to the rendezvous point; neither crew had any idea what had happened. Still, the break had at least occurred early enough that there ought still to be enough cable remaining to span the Atlantic. There was nothing for it but to splice the cables once more and try again.

This time, the distance between the ships steadily increased without further incident: 100 miles, 200 miles, 300 miles. “Why not lay 2000 [miles]!” thought Henry Field with a shiver of excitement. Then, just after the Agamemnon had made a routine splice from one spool to the next, the cable snapped in the ship’s wake. Later inspection would reveal that that section of it had been damaged in the storm. Nature’s fury had won the day after all. Again following protocol for a break this far into the cable-laying process, the two ships sailed separately back to Britain.

It was a thoroughly dejected group of men who met soon after in the offices of the Atlantic Telegraph Company. Whereas last year’s attempt to lay the cable had given reason for guarded optimism in the eyes of some of them, this latest attempt seemed an unadulterated fiasco. The inexplicable loss of signal the first time this expedition had tried to lay the cable was in its way much more disconcerting than the second, explicable disaster of a physically broken cable, as our steadfast Times of London reporter noted: “It proves that, after all that human skill and science can effect to lay the wire down with safety has been accomplished, there may be some fatal obstacle to success at the bottom of the ocean, which can never be guarded against, for even the nature of the peril must always remain as secret and unknown as the depths in which it is encountered.” The task seemed too audacious, the threats to the enterprise too unfathomable. Henry Field:

The Board was called together. It met in the same room where, six weeks before, it had discussed the prospects of the expedition with full confidence of success. Now it met as a council of war is summoned after a terrible defeat. When the Directors came together, the feeling — to call it by the mildest name — was one of extreme discouragement. They looked blankly in each other’s faces. With some, the feeling was almost one of despair. Sir William Brown of Liverpool, the first Chairman, wrote advising them to sell the cable. Mr. Brooking, the Vice-Chairman, who had given more time than any other Director, sent in his resignation, determined to take no further part in an undertaking which had proved hopeless, and to persist in which seemed mere rashness and folly.

Most of the members of the board assumed they were meeting only to deal with the practical matter of winding up the Atlantic Telegraph Company. But Cyrus Field had other ideas. When everyone was settled, he stood up to deliver the speech of his life. He told the room that he had talked to the United States and Royal Navies, and they had agreed to extend the loan of the Niagara and the Agamemnon for a few more weeks, enough to make one more attempt to lay the cable. And he had talked to his technical advisors as well, and they had agreed that there ought to be just enough cable left to span the Atlantic if everything went off without a hitch. Even if the odds against success were a hundred to one, why not try one more time? Why not go down swinging? After all, the money they stood to recoup by selling a second-hand telegraph cable wasn’t that much compared to what had already been spent.

It is a tribute to his passion and eloquence that his speech persuaded this roomful of very gloomy, very pragmatic businessmen. They voted to authorize one more attempt to create an electric bridge across the Atlantic.

The Niagara and the poor, long-suffering Agamemnon were barely given time to load coal and provisions before they sailed again, on July 17, 1858. This time the weather was propitious: blue skies and gentle breezes the whole way to the starting point. On July 29, after conducting tests to ensure that the entirety of the remaining cable was still in working order, they began the laying of it once more. Plenty of close calls ensued in the days that followed: a passing whale nearly entangled itself in the cable, then a passing merchant ship nearly did the same; more sections of cable turned up with storm-damaged insulation aboard the Agamemnon and had to be cut away, to the point that it was touch and go whether Ireland or the end of the last spool would come first. And yet the telegraph operators aboard each of the ships remained in contact with one another day after day as they crept further and further apart.

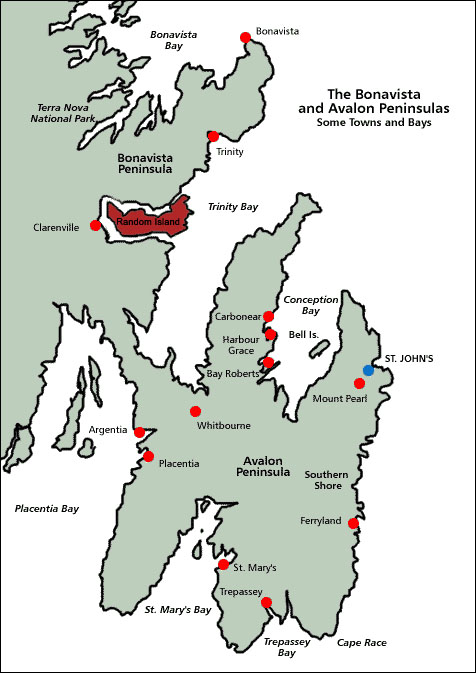

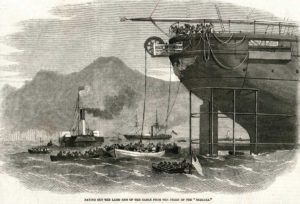

At 1:45 AM on August 6, the Niagara dropped anchor in Newfoundland at a point some distance west of St. John’s, in Trinity Bay, where a telegraph house had already been built to receive the cable. One hour later, the telegraph operator aboard the ship received a message from the Agamemnon that it too had made landfall, in Ireland. Cyrus Field’s one-chance-in-a-hundred gamble had apparently paid off.

Shouting like a lunatic, Field burst upon the crew manning the telegraph house, who had been blissfully asleep in their bunks. At 6:00 AM, the men spliced the cable that had been carried over from the Niagara with the one that went to St. John’s and beyond. Meanwhile, on the other side of the ocean, the crew of the Agamemnon was doing the same with a cable that stretched from the backwoods of southern Ireland to the heart of London. “The communication between the Old and the New World [has] been completed,” wrote the Times of London reporter.

The (apparently) successful laying of the cable in 1858 sparked almost a religious fervor, as shown in this commemorative painting by William Simpson, in which the Niagara is given something very like a halo as it arrives in Trinity Bay.

The news of the completed Atlantic cable was greeted with elation everywhere it traveled. Joseph Henry wrote in a public letter to Cyrus Field that the transatlantic telegraph would “mark an epoch in the advancement of our common humanity.” Scientific American wrote that “our whole country has been electrified by the successful laying of the Atlantic telegraph,” and Harper’s Monthly commissioned a portrait of Field for its cover. Countless cities and towns on both sides of the ocean held impromptu jubilees to celebrate the achievement. Ringing church bells, booming cannon, and 21-gun rifle salutes were the order of the day everywhere. Men who had or claimed to have sailed aboard the Niagara or the Agamemnon sold bits and pieces of leftover cable at exorbitant prices. Queen Victoria knighted the 26-year-old Charles Bright, and said she only wished Cyrus Field was a British citizen so she could do the same for him. On August 16, she sent a telegraph message to the American President James Buchanan and was answered in kind; this herald of a new era of instantaneous international diplomacy brought on yet another burst of public enthusiasm.

Indeed, the prospect of a worldwide telegraph network — for, with the Atlantic bridged, could the Pacific and all of the other oceans be far behind? — struck many idealistic souls as the facilitator of a new era of global understanding, cooperation, and peace. Once we allow for the changes that took place in rhetorical styles over a span of 140 years, we find that the most fulsome predictions of 1858 have much in common with those that would later be made with regard to the Internet and its digital World Wide Web. “The whole earth will be belted with electric current, palpitating with human thoughts and emotions,” read the hastily commissioned pamphlet The Story of the Telegraph.[1]No relation to the much more comprehensive history of the endeavor which Henry Field would later write under the same title. “It is impossible that old prejudices and hostilities should longer exist, while such an instrument has been created for the exchange of thoughts between all the nations of the earth.” Indulging in a bit of peculiarly British wishful thinking, the Times of London decided that “the Atlantic telegraph has half undone the Declaration of 1776, and has gone far to make us once again, in spite of ourselves, one people.” Others found prose woefully inadequate for the occasion, found they could give proper vent to their feelings only in verse.

‘Tis done! The angry sea consents,

The nations stand no more apart,

With clasped hands the continents

Feel throbbings of each other’s heart.Speed, speed the cable; let it run

A loving girdle round the earth,

Till all the nations ‘neath the sun

Shall be as brothers of one hearth;As brothers pledging, hand in hand,

One freedom for the world abroad,

One commerce every land,

One language and one God.

But one fact was getting lost — or rather was being actively concealed — amidst all the hoopla: the Atlantic cable was working after a fashion, but it wasn’t working very well. Even William Thomson’s new galvanometer struggled to make sense of a signal that grew weaker and more diffuse by the day. To compensate, the operators were forced to transmit more and more slowly, until the speed of communication became positively glacial. Queen Victoria’s 99-word message to President Buchanan, for example, took sixteen and a half hours to send — a throughput of all of one word every ten minutes. The entirety of another day’s traffic consisted of:

Repeat please.

Please send slower for the present.

How?

How do you receive?

Send slower.

Please send slower.

How do you receive?

Please say if you can read this.

Can you read this?

Yes.

How are signals?

Do you receive?

Please send something.

Please send Vs and Bs.

How are signals?

Cyrus Field managed to keep these inconvenient facts secret for some time while his associates scrambled fruitlessly for a solution. When Thomson could offer him no miracle cure, he turned back to Wildman Whitehouse. Insisting that there was no problem with his cable design which couldn’t be solved by more power, Whitehouse hooked it up to giant induction coils to try to force the issue. Shortly after he did so, on September 1, the cable failed completely. Thomson and others were certain that Whitehouse had burned right through the cable’s insulation with his high-voltage current, but of course it is impossible to know for sure. Still, that didn’t stop Field from making an irrevocable break with Whitehouse; he summarily fired him from the company. In response, Whitehouse went on a rampage in the British press, denouncing the “frantic fooleries of the Americans in the person of Cyrus W. Field”; he would soon publish a book giving his side of the story, filled with technical conclusions which history has demonstrated to be wrong.

On October 20, with all further recourse exhausted, Field bit the bullet and announced to the world that his magic thread was well, truly, and hopelessly severed. The press at both ends of the cable turned on a dime. The Atlantic Telegraph Company and its principal face were now savaged with the same enthusiasm with which they had so recently been praised. Many suspected loudly that it had all been an elaborate fraud. “How many shares of stock did Mr. Field sell in August?” one newspaper asked. (The answer: exactly one share.) The Atlantic Telegraph Company remained nominally in existence after the fiasco of 1858, but it would make no serious plans to lay another cable for half a decade.

Cyrus Field himself was, depending on whom you asked, either a foolish dreamer or a cynical grifter. His financial situation too was not what it once had been. His paper business had suffered badly in the panic of 1857; then came a devastating warehouse fire in 1860, and he sold it shortly thereafter at a loss. In April of 1861, the American Civil War, the product of decades of slowly building tension between the country’s industrial North and the agrarian, slave-holding South, finally began in earnest. Suddenly the paeans to universal harmony which had marked a few halcyon weeks in August of 1858 seemed laughable, and the moneyed men of Wall Street turned their focus to engines of war instead of peace.

Yet the British government at least was still wondering in its stolid, sluggish way how a project to which it had contributed considerable public resources, which had in fact nearly gotten one of Her Majesty’s foremost ships of the line sunk, had wound up being so useless. The same month that the American Civil War began, it formed a commission of inquiry to examine both this specific failure and the future prospects for undersea telegraphy in general. The commission numbered among its members none other than Charles Wheatstone, along with William Cooke one of the pair of inventors who had set up the first commercial telegraph line in the world. It read its brief very broadly, and ranged far afield to address many issues of importance to a slowly electrifying world. Most notably, it defined the standardized units of electrical measurement that we still use today: the watt, the volt, the ohm, and the ampere.

But much of its time was taken up by a war of words between Wildman Whitehouse and William Thomson, each of whom presented his case at length and in person. While Whitehouse laid the failure of the first transatlantic telegraph at the feet of a wide range of factors that had nothing to do with his cable but much to do with the gross incompetence of the Atlantic Telegraph Company in laying and operating it, Thomson argued that the choice of the wrong type of cable had been the central, precipitating mistake from which all of the other problems had cascaded. In the end, the commission found Thomson’s arguments more convincing; it did seem to it that “the heavier the cable, the greater its durability.” Its final conclusions, delivered in July of 1863, were simultaneously damning toward many of the specific choices of the Atlantic Telegraph Company and optimistic that a transatlantic telegraph should be possible, given much better planning and preparation. The previous failures were, it said, “due to causes which might have been guarded against had adequate preliminary investigation been made.” Nevertheless, “we are convinced that this class of enterprise may prove as successful as it has hitherto been disastrous.”

Meanwhile, even in the midst of the bloodiest conflict in American history, all Cyrus Field seemed to care about was his once and future transatlantic telegraph. Graduating from the status of dreamer or grifter, he now verged on becoming a laughingstock in some quarters. In New York City, for example, “he addressed the Chamber of Commerce, the Board of Brokers, and the Corn Exchange,” writes Henry Field, “and then he went almost literally door to door, calling on merchants and bankers to enlist their aid. Even of those who subscribed, a large part did so more from sympathy and admiration of his indomitable spirit than from confidence in the success of the enterprise.” One of his marks labeled him with grudging admiration “the most obstinately determined man in either hemisphere.” Yet in the course of some five years of such door-knocking, he managed to raise pledges amounting to barely one-third of the purchase price of the first Atlantic cable — never mind the cost of actually laying it. This was unsurprising, in that there lay a huge unanswered question at the heart of any renewal of the enterprise: a cable much thinner than the one which almost everyone except Wildman Whitehouse now agreed was necessary had dangerously overburdened two of the largest ships in the world, very nearly with tragic results for one of them. And yet, in contrast to the 2500 tons of Whitehouse’s cable, Thomson’s latest design was projected to weigh 4000 tons. How on earth was it to be laid?

But Cyrus Field’s years in the wilderness were not to last forever. In January of 1864, in the course of yet another visit to London, he secured a meeting with Thomas Brassey, one of the most famous of the new breed of financiers who were making fortunes from railroads all over the world. Field wrote in a letter immediately after the meeting that “he put me through such a cross-examination as I had never before experienced. I thought I was in the witness box.” (He doesn’t state in his letter whether he noticed the ironic contrast with the way this whole adventure had begun exactly one decade earlier, when it had been Frederick Gisborne who had come with hat in hand to his own stateroom for an equally skeptical cross-examination.)

It seems that Field passed the test. Brassey agreed to put some of his money and, even more importantly, his sterling reputation as one of the world’s foremost men of business behind the project. And just like that, things started to happen again. “The wheels were unloosed,” writes Henry Field, “and the gigantic machinery began to revolve.” The money poured in; the transatlantic telegraph was on again. Cyrus Field placed an order for a thick, well-insulated cable matching Thomson’s specifications. The only problem remaining was the same old one of how to actually get it aboard a ship. But, miraculously, Thomas Brassey believed he had a solution for that problem too.

During the previous decade, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, arguably the greatest steam engineer of the nineteenth century, had designed and overseen the construction of what he intended as his masterpiece: an ocean liner called the Great Eastern, which displaced a staggering 19,000 tons, could carry 4000 passengers, and could sail from Britain to Australia without ever stopping for coal. It was 693 feet long and 120 feet wide, with ten steam engines producing up to 10,000 horsepower and delivering it through both paddle wheels and a screw propeller. And, most relevantly for Brassey and Field, it could carry up to 7000 tons of cargo in its hold.

Alas, its career to date read like a Greek tragedy about the sin of hubris. The Great Eastern almost literally killed its creator; undone by the stresses involved in getting his “Great Babe” built, Brunel died at the age of only 53 shortly after it was completed in 1859. During its sea trials, the ship suffered a boiler explosion that killed five men. And once it entered service, those who had paid to build it discovered that it was just too big: there just wasn’t enough demand to fill its holds and staterooms, even as it cost a fortune to operate. “Her very size was against her,” writes Henry Field, “and while smaller ships, on which she looked down with contempt, were continually flying to and fro across the sea, this leviathan could find nothing worthy of her greatness.” The Great Eastern developed the reputation of an ill-starred, hard-luck ship. Over the course of its career, it was involved in ten separate ship-to-ship collisions. In 1862, it ran aground outside New York Harbor; it was repaired and towed back to open waters only at enormous effort and expense, further burnishing its credentials as an unwieldy white elephant. Eighteen months later, the Great Eastern was retired from service and put up for sale. A financier named Daniel Gooch bought the ship for just £25,000, less than its value as scrap metal. And indeed, scrapping it for profit was quite probably foremost on his mind at the time.

But then Thomas Brassey came calling on his friend, asking what it would cost to acquire the ship for the purpose of laying the transatlantic cable. Gooch agreed to loan the Great Eastern to him in return for £50,000 in Atlantic Telegraph Company stock. And so Cyrus Field’s project acquired the one ship in the world that was actually capable of carrying Thomson’s cable. One James Anderson, a veteran captain with the Cunard Line, was hired to command it.

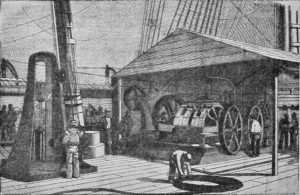

Observing the checkered record of the Atlantic Telegraph Company in laying working telegraph cables to date, Brassey and his fellow investors insisted that the latest attempt be subcontracted out to the recently formed Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company, the entity which also provided the cable itself. During the second half of 1864, the latter company extensively modified the Great Eastern for the task before it. Intended as it was for a life lived underwater, the cable was to be stored aboard the ship immersed in water tanks in order to prevent its vital insulation from drying out and cracking.

Then, from January to July of 1865, the Great Eastern lay at a dock in Sheerness, England, bringing about 20 miles of cable per day onboard. The pendulum had now swung again with the press and public: the gargantuan ship became a place of pilgrimage for journalists, politicians, royalty, titans of industry, and ordinary folks, all come to see the progress of this indelible sign of Progress in the abstract. Cyrus Field was so caught up in the excitement of an eleven-year-old dream on the cusp of fulfillment that he hardly noticed when the final battle of the American Civil War ended with Southern surrender on April 9, 1865, nor the shocking assassination of the victorious President Abraham Lincoln just a few days later.

On July 15, the Great Eastern put to sea at last, laden with the 4000 tons of cable plus hundreds more tons of dead weight in the form of the tanks of water that were used to store it. Also aboard was a crew of 500 men, but only a small contingent of observers from the Atlantic Telegraph Company, among them the Field brothers and William Thomson. Due to its deep draft, the Great Eastern had to be very cautious when sailing near land; witness its 1862 grounding in New York Harbor. Therefore a smaller steamer, the Caroline, was enlisted to bring the cable ashore on the treacherous southern coast of Ireland and to lay the first 23 miles of it from there. On the evening of July 23, the splice was made and the Great Eastern took over responsibility for the rest of the journey.

So, the largest ship in the world made its way westward at an average speed of a little over six knots. Cyrus Field, who was prone to seasickness, noted with relief how different an experience it was to sail on a behemoth like this one even in choppy seas. He and everyone else aboard were filled with optimism, and with good reason on the whole; this was a much better planned, better thought-through expedition than those of the Niagara and the Agamemnon. Each stretch of cable was carefully tested before it fell off the stern of the ship, and a number of stretches were discarded for failing to meet Thomson’s stringent standards. Then, too, William Everett’s paying-out mechanism had been improved such that it could now reel cable back in again if necessary; this did indeed prove to be the case twice, when stretches of cable proved not to be as water-resistant as they ought to have been despite all of Thomson’s efforts.

The days went by, filled with minor snafus to be sure, but nothing that hadn’t been anticipated. The stolid and stable Great Eastern, writes Henry Field, “seemed as if made by Heaven to accomplish this great work of civilization.” And the cable itself continued to work even better than Thomson had said it would; the link with Ireland remained rock-solid, with a throughput to which Whitehouse’s cable could never have aspired.

At noon on August 2, the Great Eastern was well ahead of schedule, already almost two-thirds of the way to Newfoundland, when a fault was detected in the stretch of cable just laid. This was annoying, but nothing more than that; it had, after all, happened twice before and been dealt with by pulling the bad stretch out of the water and discarding it. But in the course of hauling it back in this time, an unfortunate burst of wind and current spelled disaster: the cable was pulled taut by the movement of the ship and snapped.

Captain Anderson had one gambit left — one more testament to the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company’s determination to plan for every eventuality. He ordered the huge grappling hook with which the Great Eastern had been equipped to be deployed over the side. It struck the naïve observers from the Atlantic Telegraph Company as an absurd proposition; the ocean here was two and a half miles deep — so deep that it took the hook two hours just to touch bottom. The ship steamed back and forth across its former course all night long, dragging the hook patiently along the ocean floor. Early in the morning, it caught on something. The crew saw with excitement that, as the grappling machinery pulled the hook gently up, its apparent weight increased. This was consistent with a cable, but not with anything else that anyone could conceive. But in the end, the increasing weight of it proved too much. When the hook was three quarters of a mile above the ocean floor, the rope snapped. Two more attempts with fresh grappling hooks ended the same way, until there wasn’t enough rope left aboard to touch bottom.

It had been a noble attempt, and had come tantalizingly close to succeeding, but there was nothing left to do now but mark the location with a buoy and sail back to Britain. “We thought you went down!” yelled the first journalist to approach the Great Eastern when it reached home. It seemed that, in the wake of the abrupt loss of communication with the ship, a rumor had spread that it had struck an iceberg and sunk.

Although the latest attempt to lay a transatlantic cable had proved another failure, one didn’t anymore have to be a dyed-in-the-wool optimist like Cyrus Field to believe that the prospects for a future success were very, very good. The cable had outperformed expectations by delivering a clear, completely usable signal from first to last. The final sticking point had not even been the cable’s own tensile strength but rather that of the ropes aboard the Great Eastern. Henry Field:

This confidence appeared at the first meeting of directors. The feeling was very different from that after the return of the first expedition of 1858. So animated were they with hope, and so sure of success the next time, that all felt that one cable was not enough, they must have two, and so it was decided to take measures not only to raise the broken end of the cable and to complete it to Newfoundland, but also to construct and lay an entirely new one, so as to have a double line in operation the following summer.

Nothing was to be left to chance next time around. William Thomson worked with the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company to make the next cable even better, incorporating everything that had been learned on the last expedition plus all the latest improvements in materials technology. The result was even more durable, whilst weighing about 10 percent less. The paying-out mechanism was refined further, with special attention paid to the task of pulling the cable in again without breaking it. And the Great Eastern too got a refit that made it even more suited to its new role in life. Its paddle wheels were decoupled from one another so each could be controlled separately; by spinning one forward and one backward, the massive ship could be made to turn in its own length, an improvement in maneuverability which should make grappling for a lost cable much easier. Likewise, twenty miles of much stronger grappling rope was taken onboard. Meanwhile the Atlantic Telegraph Company was reorganized and reincorporated as the appropriately trans-national Anglo-American Telegraph Company, with an initial capitalization of £600,000.

This time the smaller steamer William Corry laid the part of the cable closest to the Irish shore. On Friday, July 13, 1866, the splice was made and the Great Eastern took over. The weather was gray and sullen more often than not over the following days, but nothing seemed able to dampen the spirit of optimism and good cheer aboard; many a terrible joke was made about “shuffling off this mortal coil.” As they sailed along, the crew got a preview of the interconnected world they were so earnestly endeavoring to create: the long tether spooling out behind the ship brought them up-to-the-minute news of the latest stock prices on the London exchange and debates in Parliament, as well as dispatches from the battlefields of the Third Italian War of Independence, all as crystal clear as the weather around them was murky.

The Great Eastern maintained a slightly slower pace this time, averaging about five knots, because some felt that some of the difficulties last time had resulted from rushing things a bit too much. Whether due to the slower speed or all of the other improvements in equipment and procedure, the process did indeed go even more smoothly; the ship never failed to cover at least 100 miles — usually considerably more — every day. The Great Eastern sailed unperturbed beyond the point where it had lost the cable last time. By July 26, after almost a fortnight of steady progress, the excitement had reached a fever pitch, as the seasoned sailors aboard began to sight birds and declared that they could smell the approaching land.

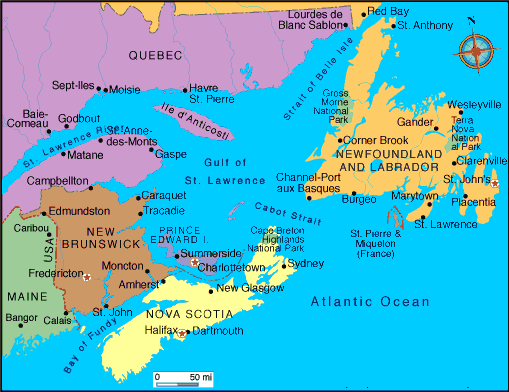

The following evening, they reached their destination. “The Great Eastern,” writes Henry Field, “gliding in as if she had done nothing remarkable, dropped her anchor in front of the telegraph house, having trailed behind her a chain of 2000 miles, to bind the Old World to the New.” A different telegraph house had been built in Trinity Bay to receive this cable, in a tiny fishing village with the delightful name of Heart’s Content. The entire village rowed out to greet the largest ship by almost an order of magnitude ever to enter their bay, all dressed in their Sunday best.

The Great Eastern in Trinity Bay, 1866. This photograph does much to convey the sheer size of the ship. The three vessels lying alongside it are all oceangoing ships in their own right.

But there was one more fly in the ointment. When he came ashore, Cyrus Field learned that the underwater telegraph line he had laid between Newfoundland and Cape Breton ten years before had just given up the ghost. So, there was a little bit more work to be done. He chartered a coastal steamer to take onboard eleven miles of Thomson’s magic cable from the Great Eastern and use it to repair the vital span; such operations in relatively shallow water like this had by now become routine, a far cry from the New York, Newfoundland, and London Telegraph Company’s wild adventure of 1855. While he waited for that job to be completed, Field hired another steamer to bring news of his achievement to the mainland along with a slew of piping-hot headlines from Europe to serve as proof of it. It was less dramatic than an announcement via telegraph, but it would have to do.

Thus word of the completion of the first truly functional transatlantic telegraph cable, an event which took place on July 27, 1866, didn’t reach the United States until July 29. It was the last delay of its kind. Two separate networks had become one, two continents sewn together using an electric thread; the full potential of the telegraph had been fulfilled. The first worldwide web, the direct ancestor and prerequisite of the one we know today, was a reality.

(Sources: the books The Victorian Internet by Tom Standage, Power Struggles: Scientific Authority and the Creation of Practical Electricity Before Edison by Michael B. Schiffer, Lightning Man: The Accursed Life of Samuel F.B. Morse by Kenneth Silverman, A Thread across the Ocean: The Heroic Story of the Transatlantic Telegraph by John Steele Gordon, and The Story of the Atlantic Telegraph by Henry M. Field. Online sources include “Heart’s Content Cable Station” by Jerry Proc, Distant Writing: A History of the Telegraph Companies in Britain between 1838 and 1868 by Steven Roberts, and History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | No relation to the much more comprehensive history of the endeavor which Henry Field would later write under the same title. |

|---|