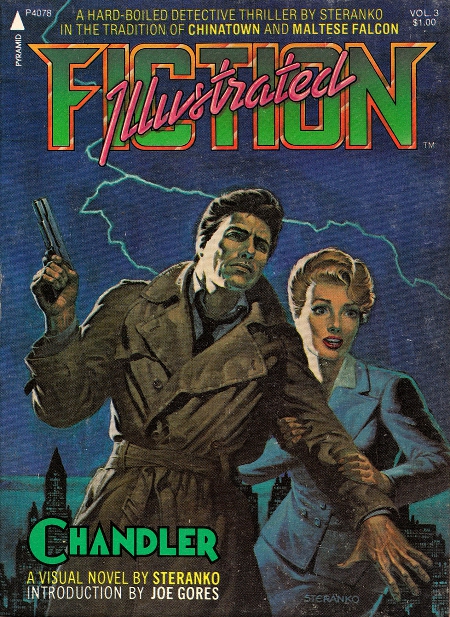

When we started out with Mean Streets, we wanted a vintage, hard-boiled detective from the 1930s and 1940s. You know, the Humphrey Bogart, Raymond Chandler classic character. But since then, we’ve changed our picture of [our detective] Tex [Murphy]. We want to see some human vulnerability. We don’t want the superhero. Too much of the videogame genre is just these invincible characters. They aren’t real; they don’t have texture; they don’t have any kind of fabric to their personality. It’s not very interesting really, dealing strictly with such a one-dimensional character.

For us, the idea was to make this person seem more real. Whether he’s fumbling around or whatever — okay, let’s give him a talent, but let’s put a few defects in his character. He’s still a good guy, but he screws up a lot and says the wrong thing. He’s really from a different time period. We set it in the future because we wanted to give it the gadgets and get it out of today. So we take this man out of time. The general focus of Tex is this: I’m this guy who’s got these problems, who tries to date women but has a hard time with it, and ends up dating the wrong women. If someone good actually likes Tex, well, he figures there must be something wrong with them.

But now, to take Tex down three different paths… this is very interesting.

— Chris Jones in 1995, speaking about plans for The Pandora Directive

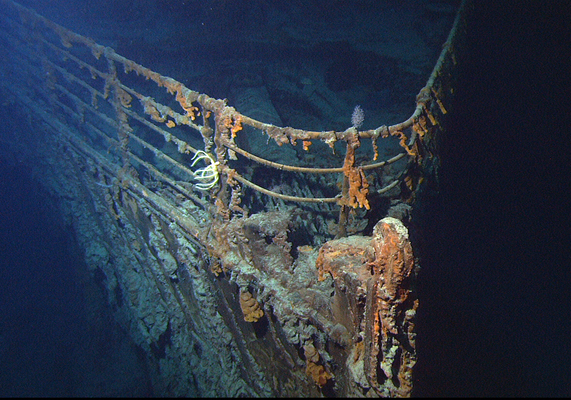

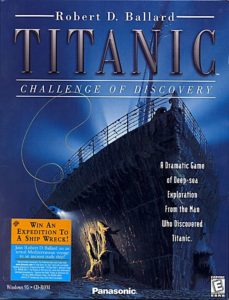

Under a Killing Moon, the first interactive full-motion-video film noir to feature the perpetually down-on-his-luck detective-out-of-time Tex Murphy, didn’t become one of that first tier of mid-1990s adventure games that sold over a million copies, captured mainstream headlines, and fomented widespread belief in a new era of interactive mainstream entertainment. It did become, however, a leading light of the second tier, selling almost half a million copies for its Salt Lake City-based developer and publisher Access Software over the course of the year after its release in late 1994. Such numbers were enough to establish Tex Murphy as something more than just a sideline to Links, Access’s enormously profitable series of golf simulations. Indeed, they made a compelling case for a sequel, especially in light of the fact that the second game ought to cost considerably less to make than the $5 million that had been invested in the first, what with the sequel being able to reuse an impressive game engine whose creation had eaten up a good chunk of that budget. The sequel was officially underway already by the beginning of 1995.

The masterminds of the project were once again Chris Jones and Aaron Conners — the former being the man who had invented the character of Tex Murphy and who still played him onscreen when not moonlighting as Access’s chief financial officer (or vice versa), the latter being the writer who had breathed new life into him for Under a Killing Moon. The sequel was to be an outlier in the novelty-driven world of game development, representing a creative and writerly evolution rather than a technological one. For the fact was that the free-roaming 3D adventuring engine used in Under a Killing Moon was still very nearly unique.

Conners concocted a new script, called The Pandora Directive, that was weightier and just plain bigger than what had come before; it was projected to require about half again as much time to play through. It took place in the same post-apocalyptic future and evinced the same Raymond Chandler-meets-Blade Runner aesthetic, but it also betrayed a marked new source of inspiration: the hit television series The X-Files, whose murky postmodern vision of sinister aliens and labyrinthine government conspiracies was creeping into more and more games during this era. Conners was forthright about its influence in interviews, revealing at the same time something of the endearingly gawky wholesomeness of The Pandora Directive‘s close-knit, largely Mormon developers, which sometimes sat a little awkwardly alongside the subject matter of their games. Watching The X-Files in secret, away from the prying eyes of spouses and children, was about as edgy as this bunch ever got in their personal lives.

Everyone else in the development team is a family man, and X-Files is a little heavy for the kids. So they all ask me to record it. I bring it in and we watch it during lunch. I really like the show. It’s been nice because we watch carefully to see what they do with music and lighting to portray a mood. Their production is closer to what we do than to a cinematic feature — tighter budget, working faster. So we found the show very informative.

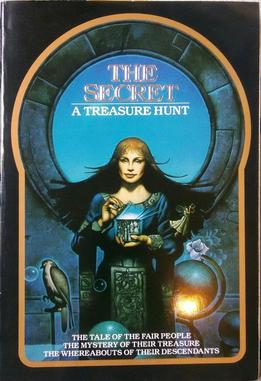

If anything, The X-Files‘s influence on The Pandora Directive‘s plot is a little too on-the-nose. Like its television inspiration, the game revolves around the UFO that allegedly crashed in Roswell, New Mexico, in 1947, the wellspring of a thousand overlapping conspiracy theories in both real life and fiction. If the one in the game is ultimately less intricately confounding than its television counterpart, that is only, one senses, because Conners had less space to develop his mythology. It’s all complete nonsense, of course, but The Pandora Directive is hardly the only game to mine escapist fun from the overwrought fever dreams of the conspiracy theorists.

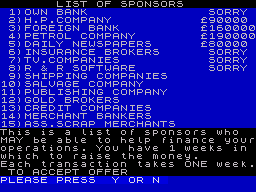

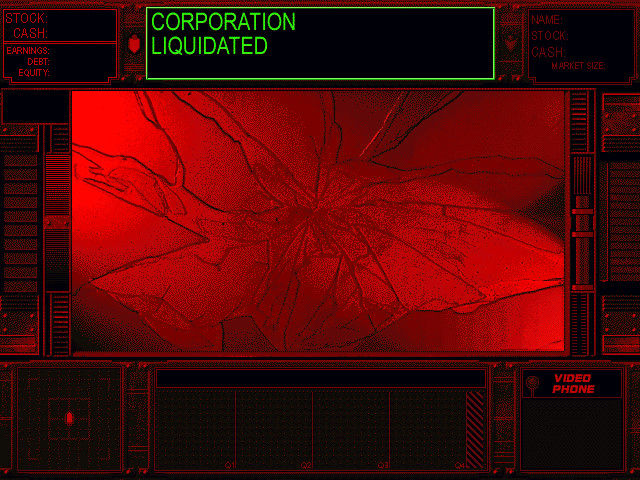

But Jones and Conners were as eager to experiment with the form of their game as its content. Like the vast majority of adventure games, Under a Killing Moon had draped only a thin skein of player agency over a plot whose broad beats were as fixed as those of any traditional novel or film. You could tinker with the logistical details, in other words — maybe do certain things in a different order from some other player — but the overall arc of the story remained fixed. Conners’s script for The Pandora Directive aimed to change that, at least partially. While your path to unraveling the conspiracy would remain mostly set in stone, you would be able to determine Tex’s moral arc, if you will. If you played him as a paragon of virtue, he might just win true love and find himself on the threshold of an altogether better life by the end of the game. Cut just a few ethical corners here and there, and Tex would finish the game more or less where he’d always been, just about managing to keep his head above water and make ends meet, in a financial and ethical sense. But play him as a complete jerk, and he’d wind up dissipated and alone. Chris Jones on the bad path, which was clearly a challenge for this particular group of people to implement:

It’s a gradual fall. Bit by bit. Bad decision here, another there. As Tex sees it and the surroundings begin to change, he realizes that he blew it. His opportunity’s gone; this other girl is dead because of his mistake. And that darkens the character. So if each step gets you just a little darker, then it’s believable. It starts to have a real texture to it. That’s what we’re trying to do. Tex makes choices, tripping down the dark path, and starts to question himself: “Do I want to save myself? Or maybe this is what I want.” And then eventually you’re trapped. And that’s when it gets very interesting. We start to give Tex some options where the player will say, “Whoa! Can I make this choice?” By the end of the game, he turns into a real cynical bastard. If he chooses to stay on the darker side — each choice is just a shade of gray really, but all those shades of gray add up to a pretty dark character by the time you’re done. Just like in life.

I’m a bit uncomfortable about the way the [dark] path turns out. That was never my vision of what Tex could be. On the other hand, we have this medium which allows you to do such a thing. It is our competitive advantage over movies and television to be able to say to our audience, “Sit in this seat, make different decisions, and see how it turns out.” If we can pull it off with our characterizations and acting… well, now, that’s a very powerful medium. And so I feel like we have a responsibility to do that, to provide these kinds of choices. As I said, as an actor, I feel uncomfortable with this portrayal of Tex. But I feel it would shortchange people who buy the game to say, no, this is Tex, do it my way. If you’re kind of leaning down the dark path, take it and see what happens. You become the character. I’m in your hands.

In addition to the artistic impulse behind it, the more broad-brushed interactivity was intended to allay one of the most notable weaknesses of adventure games as a commercial proposition: the fact that they cost as much or more than other types of games to buy, but, unlike them, were generally interesting to play through only once. Jones and Conners hoped that their players would want to experience their game two or three times, in order to explore the possibility space of Tex’s differing moral arcs.

They implemented a user-selectable difficulty level, another rarity in adventure games, for the same reason. The “Entertainment” level gives access to a hint system; the “Game Players” level removes that, whilst also removing some in-game nudges, adding some red herrings to throw you off the scent, making some of the puzzles more complex, and adding time limits here and there. Again, Jones and Conners imagined that many players would want to go through the story once at Entertainment level, then try to beat the game on Game Players.

But the most obvious way that Access raised the bar over Under a Killing Moon was the cast and crew that they hired for the cinematic cut scenes and dialogs that intersperse your first-person explorations as Tex Murphy. While the first games had employed such Hollywood actors as Margot Kidder, Brian Keith, Russell Means, and even the voice of James Earl Jones as its narrator, it had done so only as an afterthought, once Jones and Conners had already built the spine of their game around local Salt Lake City worthies. This time they chose to invest a good part of the money they had saved from their tools budget into not just “real” actors but a real, professional director.

The official resumé which Access’s press releases provided for Adrian Carr, the man chosen for the latter role, was written on a curve typical of interactive movies, treating the five episodes he had directed of the cheesy children’s show Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, his most prominent American credit to date, like others might a prestigious feature film. “He has directed, written, and/or edited work in almost every genre, from features to documentaries, television drama to commercials,” Access wrote breathlessly. All kidding aside, Carr really was an experienced journeyman, who had directed two low-budget features in his native Australia and edited a number of films for Hollywood. He had never seriously played a computer game in his life, but that didn’t strike Jones and Conners as a major problem; they were confident that they had a handle on that side of the house. Carr was brought in not least because professional actors of the sort that he’d seen before on television or movie screens tended to intimidate Chris Jones, who’d directed Under a Killing Moon himself. He “didn’t know how to handle them exactly,” allowed Conners.

Whatever the initial impulse behind it, it proved to be a very smart move. Adrian Carr may not have been the film industry’s ideal of an auteur, but he was more than capable of giving The Pandora Directive a distinctive look that wasn’t just an artifact of the technology behind the production — a look which, once again, stemmed principally from The X-Files, from that television show’s way of portraying its shadowy conspiracies using an equally shadowy visual aesthetic. Carr:

We started lighting darker, and putting in Venetian blinds and shadows and reflections to create texture. And the poor people who render the backgrounds moaned, “But it’s so dark!” And I’d say, “But it’s a movie!”

This has been one of my contributions, I guess. The technicians have been learning about mood. Like when Tex comes home and the room is only lit from outside, or there’s just one lamp on — see, guys, the murkiness is actually good, it creates a certain texture for the mood that we want.

The cast as a whole remained a mixture of amateurs and professionals; those returning characters that had been played by locals in the previous game were still played by them in this one. Among these was Tex Murphy himself, played by Chris Jones, the man whom everyone agreed really was Tex in some existential sense; he probably wasn’t much of an actor in the abstract, probably would have been a disaster in any other role, but he was just perfect for this one. Likewise, Tex’s longtime crush Chelsee Bando and the other misfits that surround his office on Chandler Avenue all came back to make up for in enthusiasm what they lacked in acting-school credentials.

Chelsee Bando (Suzanne Barnes) is literally the girl next door; she runs a newspaper stand just outside of Tex’s office and apartment.

On the other hand, none of the professional actors make a return appearance. (I must admit that I sorely miss the dulcet tones of James Earl Jones.) The cast instead includes Tanya Roberts, who was one of Charlie’s Angels (in the show’s last season only), a Bond girl, and a Playboy centerfold during the earlier, more successful years of her career; here she plays Regan Madsen, the sultry femme fatale who may just be able to make Tex forget his unrequited love for Chelsee. Also present is Kevin McCarthy, who had been a Hollywood perennial with his name in every casting director’s Rolodex for almost half a century by the time this game was made, with his role in the 1956 B-movie classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers standing out as the one real star turn on his voluminous resumé; here he plays Dr. Gordon Fitzpatrick, the former Roswell scientist who draws Tex into the case. And then there’s John Agar, who first captured international headlines back in 1945, when he married the seventeen-year-old former child star Shirley Temple. He never got quite that much attention again, but he did put together another long and fruitful career as a Hollywood supporting player; he appears here as Thomas Malloy, another would-be Roswell whistleblower.

But the Pandora Directive actor that absolutely everyone remembers is Barry Corbin, in the role of Jackson Cross, the government heavy who is prepared to shut down any and all investigations into the goings-on at Roswell by any and all means necessary. Whereas McCarthy and Agar built careers out of being handsome but not overly memorable presences on the screen — a quality which served them well in their multitude of supporting roles, in which they were expected to be competent enough to fulfill their character’s purpose but never so brilliant as to overshadow the real stars — Corbin was and is a character actor of a different, delightfully idiosyncratic type, with a look, voice, and affect so singular that millions of viewers who have never learned his name nevertheless recognize him as soon as he appears on their screen: “Oh, it’s that guy again…” At the time of The Pandora Directive, he was just coming off his most longstanding and, to my mind anyway, defining role: that of the former astronaut Maurice Minnifield, town patriarch of Cicely, Alaska, in the weird and beautiful television show Northern Exposure. In Corbin’s capable hands, Maurice became a living interrogation of red-blooded American manhood of the stoic John Wayne stripe, neglecting neither its nobility nor its toxicity, its comedy nor its pathos.

Although The Pandora Directive didn’t give Corbin an opportunity to embody a character of such well-nigh Shakespearean dimensions, it did give him a chance to have some fun. For unlike Maurice Minnifield, Jackson Cross is exactly what he appears to be on the surface: a villain’s villain of the first order. Corbin delighted in chewing up the scenery and spitting it in the face of the hapless Chris Jones — a.k.a, Tex Murphy. Jones, revealing that he wasn’t completely over his inferiority complex when it came to professional actors even after giving up the director’s job:

It’s already a little intimidating to work with people who are just consummate professionals. Then the first scene we shot together, Tex was supposed to be grilled by Barry’s character, Jackson Cross. I’m sitting in this chair, and he just came up and scared the hell out of me. Really, he looked through me and I just melted. Fortunately, that’s what my character was supposed to do. I truly felt like I was going to die if I didn’t answer him right. It was frightening.

The Pandora Directive was released with high hopes all around on July 31, 1996, about 21 months after Under a Killing Moon. It shipped on no fewer than six CDs, two more than its predecessor, a fairly accurate gauge of its additional scope and playing time.

Alas, its arrival coincided with the year of reckoning for the interactive movie as a viable commercial proposition. Despite the improved production values and the prominent placement of Barry Corbin’s unmistakable mug on the box, The Pandora Directive sold only about a third as many copies as Under a Killing Moon. Instead of pointing the way toward a new generation of interactive mainstream entertainment, it was doomed to go down in media history as an oddball artifact that could only have been created within a tiny window of time in the mid-1990s. Much like Jane Jensen in the case of The Beast Within, Chris Jones and Aaron Conners were afforded exactly one opportunity in their careers to make an interactive movie on such a scale and with such unfettered freedom as this, before the realities of a changing games industry sharply limited their options once again.

Small wonder, then, that both still speak of The Pandora Directive in wistful tones today. Developed in an atmosphere of overweening optimism, it is and will probably always remain The One for them, the game that came closest to realizing their dreams for the medium, having been created at a time when a merger of Silicon Valley and Hollywood still seemed like a real possibility, glittering and beckoning just over the far horizon.

And how well does The Pandora Directive stand up today, divorced from its intended role as a lodestar for this future of media that never came to be? Pretty darn well for such an undeniable period piece, I would say, with only a few reservations. If I could only choose one of them, I think I would be forced to go with Under a Killing Moon over this game, just because The Pandora Directive can occasionally feel a bit smothered under the weight of its makers’ ambitions, at the expense of some of its predecessor’s campy fun. That said, it’s most definitely a close-run thing; this game too has a lot to recommend it.

Certainly there’s more than a whiff of camp about it as well. As the video clip just above amply attests, not even the talented actors in the cast were taking their roles overly seriously. In fact, just like Under a Killing Moon, this game leaves me in a bit of a pickle as a critic. I’ve dinged quite a few other games on this site for “lacking the courage of their convictions,” as I’ve tended to put it, for using comedy as a crutch, a fallback position when they can’t sustain their drama for reasons of acting, writing, or technology — or, most commonly, all three. I can’t in good faith absolve The Pandora Directive of that sin, any more than I can Under a Killing Moon. And yet it doesn’t irritate me here like it usually does. I think this is because there’s such a likeability to these Tex Murphy games. They positively radiate creative joy and generosity; one never doubts for a moment that they were made by nice people. And niceness is, as I’ve also written from time to time on this site, a very undervalued quality, in art as in life. The Tex Murphy games are just good company, the kind you’re happy to invite into your home. Playing them is like watching a piece of community theater put on by your favorite neighbors. You want them to succeed so badly that you end up willing them over the rough patches with the power of your imagination.

The archetypal Access Software story for me involves a Pandora Directive character named Archie Ellis, a hapless young UFO researcher who, in the original draft of the script, stepped where he didn’t belong and got himself killed in grisly fashion by Jackson Cross. Barry Corbin “just dominates that scene,” said Aaron Conners later. “It was like we let this evil essence into the studio.” Everyone was shocked by what had been unleashed: “The mood on the set was just so oppressive.” So, Conner scurried off to doctor the script, to give the player some way to save poor little Archie, feeling as he did that what he had just witnessed was simply too “traumatic” to leave an inevitability. You can call this an abject failure on his part to stick to his dramatic guns, but it’s hard to dislike him or his game for it, any more than you can, say, make yourself dislike Steve Meretzky for bringing the lovable little robot Floyd back to life at the end of Planetfall, thereby undercutting what had been the most compelling demonstration to date of the power of games to move as well as entertain their players.

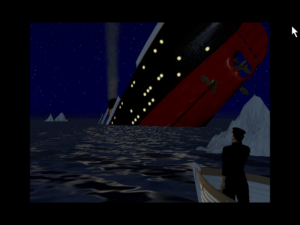

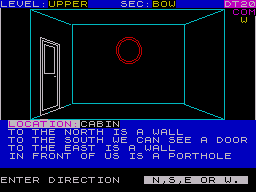

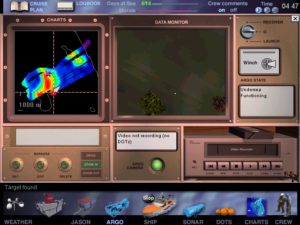

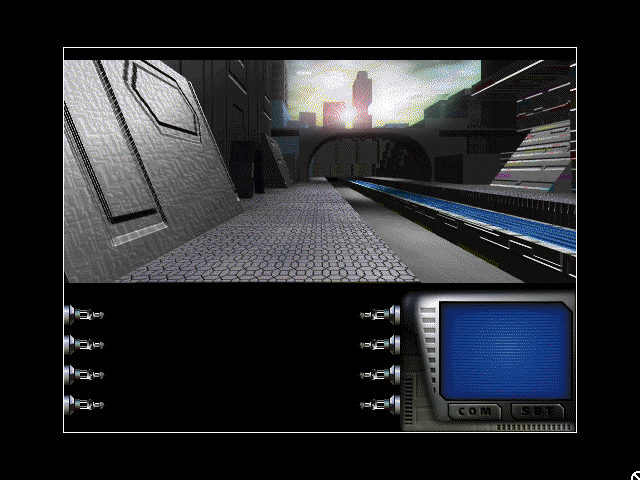

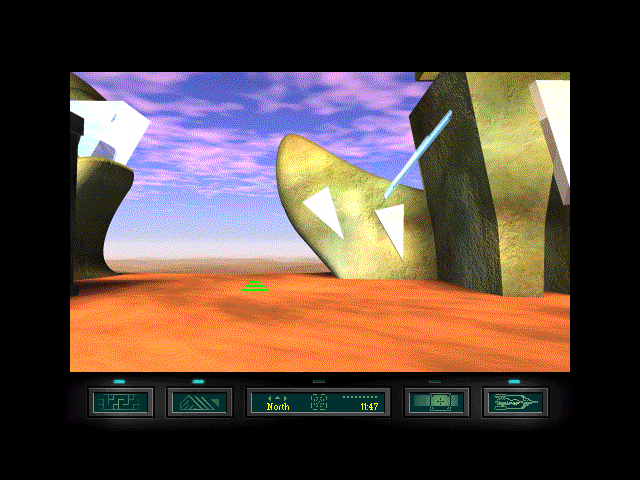

I won’t belabor the finer points of The Pandora Directive‘s gameplay and interface here because they don’t depart at all from Under a Killing Moon. The first-person 3D exploration, which lets you move freely about a space, looking up and down and peering into and over things, remains as welcome as ever; I would love it if more adventure games had been done in this style. And once again there are a bevy of set-piece puzzles to solve, from piecing torn-up notes back together to manipulating alien mechanisms. Nothing ever outstays its welcome. On the contrary, The Pandora Directive does a consistently great job of switching things up: cut scenes yield to explorations, set-piece visual puzzles yield to dialog menus. There are even action elements here, especially if you choose the Game Player mode; your furtive wanderings through the long-abandoned Roswell complex itself, dodging the malevolent alien entity who now lives here, are genuinely frightening. This 3D space and one or two others are far bigger than anything we saw in the last game, just as the puzzle chains have gotten longer and knottier. And yet there’s still nothing unfair in this game, even in Game Player mode; it’s eminently soluble if you pay attention to the details and apply yourself, and contains no hidden dead ends. Say it with me one more time: the folks who made this game were just too nice to mistreat their players in the way of so many other adventure games.

I would like to write a few more words about the game’s one big formal innovation, letting the player determine Tex’s moral arc. Jones and Conners deserve a measure of credit for even attempting such a thing in the face of technological restrictions that militated emphatically against it. Live-action video clips filled a huge amount of space and cost a lot of money to produce, such that to offer a game with branching paths, thus leaving a good chunk of the content on the CDs unseen by many players, must have cut Chris Jones’s accountant’s heart to the quick. Points for effort, then.

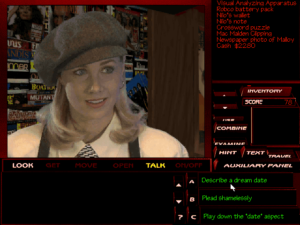

As tends to the be the case with many such experiments, however, I’m not sure how much it truly adds to the player’s final experience. One of the big problems here is the vagueness of the dialog choices you’re given. Rather than showing you exactly what Tex will say, the menus offer options like “insensitive but cheerful” or “pretend nothing’s wrong,” which are open to quite a range of overlapping interpretations. In not making Tex’s next line of dialog explicit, the designers were trying to solve another problem, that of the inherent anticlimax of clicking on a sentence and then listening to Tex dutifully parrot it back. Unfortunately, though, the two solutions conflict with one another. Far too often, you click an option thinking it means one thing, only to realize that Tex has taken it in a completely different way. This doesn’t have to happen very often before the vision of Tex the game is depicting has diverged in a big way from the one you’re trying to inhabit, making the whole exercise rather moot if not actively frustrating.

Aaron Conners himself admitted that “95 percent of the people who play will end up on the B path,” meaning the one where Tex doesn’t prove himself to be a paragon of virtue and thus doesn’t get his lady love Chelsee — not yet, anyway — but doesn’t fall into a complete moral abyss either. And indeed, this was the ending I saw after trying to play as a reasonably standup guy. (For what it’s worth, I didn’t succeed in saving poor Archie either.) Predictably enough, the Internet was filled within days of the game’s release with precise instructions on how to hack your way through the thicket of dialog choices to arrive at the best ending (or the worst one, for that matter). All of which is well and good — fans gotta fan, after all — but is nevertheless the polar opposite of the organic experience that Jones and Conners intended. Why bother adding stuff that only 5 percent of your players will see without reading the necessary choices from a walkthrough? The whole thing strikes me as an example — thankfully, a rare one — of Jones and Conners rather outsmarting themselves, delivering a feature which sounded better in interviews about the amazing potential of interactive movies than it works in practice.

Then again, the caveat and saving grace which ought to be attached to my complaints is that none of it really matters all that much when all is said and done; the B ending that most of us will see is arguably the truest to the spirit of the Tex Murphy character anyway. And today, of course, you can pick and choose in the dialogs in whatever way feels best to you, then go hunt down the alternate endings on YouTube if you like.

It may sound strange to say in relation to a game about sinister government conspiracies, set in a post-apocalyptic dystopia, but playing The Pandora Directive today feels like taking a trip back to a less troubled time. It’s just about the most 1990s thing ever, thanks not only to its passé use of video clips of real actors but to its X-Files-derived visual aesthetic, its subject matter (oh, for a time when the most popular conspiracy theories were harmless fantasies about aliens!), and even the presence of Barry Corbin, featured player in one of the decade’s iconic television programs. So, go play it, I say; go revel in its Mormon niceness. The post-millennial real world, more complicated and vexing than a thousand Roswell conspiracy theories, will still be here waiting for you when you return.

(Sources: the book The Pandora Directive: The Official Strategy Guide by Rick Barba; Electronic Entertainment of July 1995; Computer Gaming World of March 1996 and December 1996; Retro Gamer 160. Online sources include the now-defunct Unofficial Tex Murphy Web Site and a documentary film put out by Chris Jones and Aaron Conners in recent years.

The Pandora Directive is available from GOG.com as a digital purchase.)