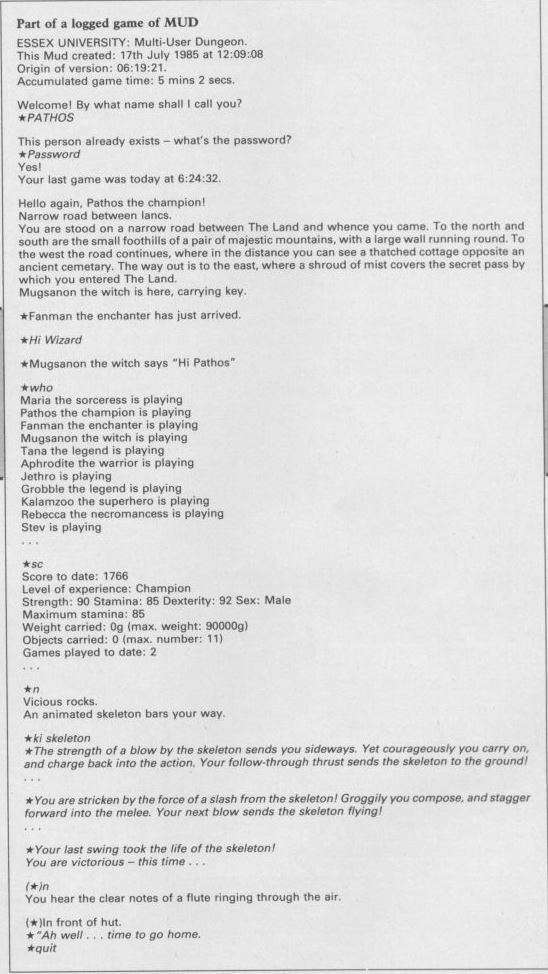

You are stood on a narrow road between The Land and whence you came. To the north and south are the small foothills of a pair of majestic mountains, with a large wall running round. To the west the road continues, where in the distance you can see a thatched cottage opposite an ancient cemetery. The way out is to the east, where a shroud of mist covers the secret path by which you entered The Land.

— the first text players saw upon entering the University of Essex MUD

During the time when the original PDP-10 Zork was the hottest game in institutional computing, a fair number of overseas visitors managed to access the machine that ran it at MIT’s Dynamic Modeling Group. One day in 1980, one such visitor, from the University of Essex in Britain, left a strange message on the Zork mailing list: “You haven’t lived ’til you’ve died in MUD.”

When the folks inside MIT investigated, they learned that the spirit of hacker oneupsmanship which had caused them to beget Zork as a response to Crowther and Woods’s Adventure had finally come back around to bite them. Zork had perfected the Adventure formula at the same time that it exploded it, applying a much more advanced parser and a much more detailed and coherent world model to a game that was several times as big. Now, MUD — the Multi-User Dungeon — was taking the next step, applying the innovations of its predecessors to the world’s first shared persistent virtual world. The creators of MUD had first encountered Zork in the form of an unauthorized port which bore the name of Dungeon; thus the name of Multi-User Dungeon made the challenge to the existing state of the art in text adventures all too plain.

Later in 1980, Dave Lebling of the Dynamic Modeling Group penned an article for Byte magazine about Zork which, not coincidentally, included this musing about possible future directions:

Another area where experimentation is going on is that of multiplayer CFS [computerized fantasy simulation] games. Each player (possibly not even aware how many others are playing) would see only his own view of the territory. He would be notified when other players enter or leave the room, and could talk to them.

This would not, however, be the road which Lebling and his colleagues would ultimately choose to go down. Instead they would focus their energies on crafting the most polished, compelling single-player text adventures they possibly could, forming the company known as Infocom to publish them on the microcomputers of the time — a story regular readers of this blog already know well.

And yet the idea of the multi-player text adventure — and with it the idea of a text adventure that was a persistent world to be visited again and again rather than a single game to be solved and set aside — wasn’t going to go away either. On the contrary: a direct line can be traced from Adventure and Zork through MUD and its many antecedents, and on to the functioning virtual societies, with populations in some cases bigger than many small countries here on our real planet, that are the persistent online worlds of today.

As has been the case for more seminal developments in computing history than some might like to admit, MUD was spawned less by a grand theoretical vision than a technical quirk in the computer which ran it. In fact, it was the very same quirk as that which would lead Sandy Trevor over at CompuServe in the United States to create the equally seminal CB Simulator, the world’s first real-time chat program.

The big DEC PDP-10 computer, a staple of institutional computing and with it of hacker culture during the 1970s, might host dozens of simultaneous users, many of whom might be running the same program. It would be absurdly wasteful of precious memory to copy this program’s code over and over into each individual user’s private memory space. Therefore each user was given access to two pools of memory. One, used for program code, was shared among all users on the system — so that if, say, many of them were running the same text editor then the code for that text editor would have to exist in the computer’s memory in only one place. The other area was reserved for the unique data — in this example, the actual file being edited — that each user was working with; this private space could only be accessed by her. In itself, none of this constituted a quirk; it was just good system design, and as such is still used by most computers today.

But something that was a little quirky about the PDP-10 was noticed by a University of Essex student named Roy Trubshaw in 1977: the fact that nothing absolutely demanded that only static program code, as opposed to dynamic data of other sorts, reside in the shared memory space. With a bit of trickery, the PDP-10 could be convinced to use the shared space to facilitate real-time communications between users who would otherwise be isolated inside their own bubbles. Trubshaw’s first experiments along these lines were as basic as could be: he wrote a couple of programs to cause one user’s terminal to echo text being typed into another’s. “It might seem odd to someone who wasn’t there,” he remembers, “but the feeling of achievement when the line of text on one teletype appeared as typed on the second teletype was just awesome.” From such experiments would eventually spring MUD — for, Trubshaw would realize, there was nothing preventing the shared memory space from containing an entire virtual world rather than just lines of typed text.

The road from typed text to virtual world would, like so much else in gaming history, pass through Adventure. The year of 1977 was also the year of Will Crowther and Don Woods’s pioneering creation, which fascinated Trubshaw as much as it did all of the other hackers who encountered it. The source code to Adventure fortuitously popped up on the University of Essex’s PDP-10 the following year, while Trubshaw was still tinkering with his shared-memory experiments. Taking inspiration from Crowther and Woods’s code — but not too much; he considered the game’s implementation “by and large a giant kludge” — Trubshaw developed a markup language for describing a shared world, to be brought to life by an interpreter program. He named his new language MUDDL, for Multi-User Dungeon Development Language. (MUDDL was an amusing if coincidental echo of MDL — pronounced “muddle” — the language the Dynamic Modeling Group at MIT had used to implement Zork. Ditto Infocom’s later MDL-based in-house language, ZIL: the Zork Implementation Language.) The first MUDDL-built shared world to go online modeled, in the grand tradition of countless other first text-adventure creations, the house where Trubshaw had grown up and where his parents still lived. While it’s difficult to anchor these developments precisely in time, the project may have reached this point as early as late 1978, and certainly by 1979.

Trubshaw’s most enthusiastic fan and assistant was an undergraduate named Richard Bartle with a taste for Tolkien, Dungeons & Dragons, and the single-player text adventures, like Adventure and Zork, which echoed them. With that perfect resume to hand, Bartle began to function as the world designer for the nascent MUD. In the spring of 1980, shortly after Trubshaw and Bartle together had posted that cryptic message to the Zork mailing list, Trubshaw graduated from university — he blamed the time spent working on MUD for having finished with a second rather than a first — and moved to Belgium, bequeathing all of his old code unto Bartle. Trubshaw wouldn’t do any more serious work on MUD for the next several years, and would only very rarely visit it as a player. From this point on, it would be Richard Bartle’s baby. (There is an interesting parallel here with the original Adventure, which was started by Will Crowther largely as a coding experiment, only to be abandoned by him and developed into a full-fledged game later by Don Woods. The notable difference is that Trubshaw and Bartle, unlike Crowther and Woods, did know one another, and actually worked together on the project for a while.)

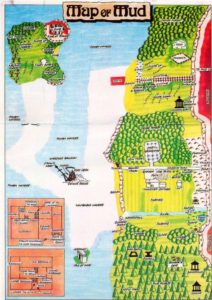

Bartle was now working earnestly on making the world of MUD, which he called simply The Land, into a place worth visiting. From its modest beginnings as a facsimile of Trubshaw’s parents’ house it would grow over the course of years to become an immense place, with some 600 rooms, encompassing everything from the expected Tolkienesque fantasy to an area based — without authorization, of course — on Jim Henson’s Fraggle Rock television program.

At first, The Land was inhabited only by a select group of University of Essex students who could locally access the PDP-10 on which it ran. The same PDP-10 was, however, also accessible by a privileged few outside the university who had managed to finagle, by means legal or extra-legal, access to the early Internet. One of the first such outsiders to drop by was a precocious 17-year-old named Jeremy San who spent his days prowling the Internet, looking for interesting things. MUD, he knew immediately, was very interesting indeed. He became its greatest propagandist among the tiny British modem fraternity of the time; a huge percentage of the people who wound up playing MUD did so thanks to his encouragement. (Jeremy San took the handle of “Jez” on MUD, a nickname which leaked out of its virtual context to become his professional name. As Jez San, he would go on to become a major figure in British game development, responsible for Starglider among other hits.)

Enough outsiders like San were soon playing MUD to prompt the division of players into “internals,” meaning people playing from within the university itself, and “externals,” meaning people logging on from outside its hallowed halls. The university’s administrators proved rather astonishingly generous with their computing resources, allowing players from all over the country and, eventually, all over the world to log on and play during evenings and weekends. But make no mistake: doing so was a tall order in the Britain of the early 1980s, where electronic communications in general were still in a far more primitive state than the United States of the period, where even simple local phone calls were still charged by the minute and modems were rarer than hen’s teeth among home-computer owners. To add to the logistical difficulties, MUD didn’t even become available on the university’s PDP-10 until 1:00 AM, after everyone else had presumably finished doing their real work on the machine. Nevertheless, enough people combined the requisite privilege, cleverness, and dedication that the software’s limitation of no more than 36 simultaneous players quickly began to frustrate.

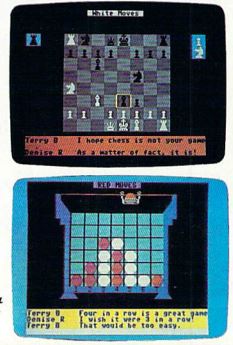

For all that even MUD‘s very name implied it to be nothing more than a multiplayer version of Zork/Dungeon, the move from a single-player game to be solved and set aside to a persistent world to be inhabited by the same players for months or years changed everything. The design questions which confronted Bartle were completely different from those being debated contemporaneously inside the early Infocom. In fact, they had far more in common with those still being debated by the makers of the massively-multiplayer games of today than they did with those surrounding the single-player games of their own time. In a single-player game, the player is the star of the show; the (virtual) world revolves around her. Not so inside The Land. Most traditional text-adventure puzzles made no sense at all there. The first person to come along and solve a puzzle might have fun with it, but after that the shared world meant that what was solved for one was solved for all: the door remained unlocked, the drawbridge remained lowered, etc. This was not, needless to say, a good use of a designer’s energy. MUD did include some set-piece puzzles which could be solved by simply typing an answer, without affecting the environment — riddles, number sequences, etc. — but even these became mere pointless annoyances to a player after she had solved them once, and tended to be so widely spoiled by the first player to solve them that they too hardly seemed a good use of a designer’s time.

The most innovative puzzles in The Land were those which took advantage of this being a multiplayer text adventure to demand cooperation; think of a heavy portcullis which can only be lifted by several players straining together. Perhaps the cleverest example of this species of puzzle was The Swamp, a huge maze with an immensely valuable crown hidden at its center. Because it was a swamp, the tried-and-true drop-and-plot technique for solving mazes was a nonstarter; items dropped would just disappear below the surface. The only way to defeat the maze was rather with a team of a dozen or more players, leaving one player behind in each room to mark its identity.

Yet puzzles — even brilliant puzzles like this one — were never really the heart of MUD‘s appeal; even the Swamp maze became a fairly rote exercise as soon as the first group figured out how to approach it. Although it presented itself in the guise of a text adventure, MUD often played more like a CRPG. Replacing the deterministic behavior of Adventure and Zork was a focus on emergent behavior. Each player had scores for strength, stamina, and dexterity, which determined the outcome of many actions, including combat with the many creatures which dotted the landscape. These attributes increased as one’s in-game accomplishments grew.

Like most traditional text adventures, MUD had a system of points for measuring the player’s achievements. Less typically, but very much in keeping with the CRPG side of the game’s personality, this score translated into levels, which among other things allowed players to attach honorifics (“Hero,” etc.) to their names. Points became a sort of currency within The Land; it was possible to transfer some of your points to another player by “hugging” or “kissing” her, and this was often done in exchange for goods and services.

The most straightforward way of scoring points, however, was at first glance lifted straight from Adventure and Zork: treasures were scattered about The Land, which players could retrieve and drop into a designated location. But this scheme alone was obviously unsuitable to a multiplayer context, at least if Bartle didn’t want to spend all his time hiding new treasures for players to discover. Instead he came up with a scheme, always more tolerated than liked by even the most dedicated players, by which The Land was periodically “reset,” with all treasures moved back to their original starting locations. Such resets, besides being something of a blight on MUD‘s very identity as an allegedly persistent online world, were an imperfect solution in that the more experienced players were the ones who knew where the treasures lay after a reset; they thus could rush over to claim them before the newbies had a chance. It would often take the veterans no more than five minutes to scarf up all the treasures during a “reset rush hour,” an exercise as unchallenging for them as it was baffling for the newbies.

But then, the same newbies who were left nonplussed by the reset rush hour soon found much worse to complain about. Not only did MUD feature permadeath, but it allowed its experienced players to kill the new ones. Indeed, it even encouraged such behavior by rewarding the griefers with one-twenty-fourth of the points their victims had accumulated over the course of their careers. Combined with the cliquey nature of MUD‘s culture, it could make The Land a hugely off-putting place to visit for the first time.

Tormenting the newbies was a favorite pastime among the regulars. Richard Bartle tells the sad story of one of MUD‘s first two externals, who managed to connect from all the way over in the United States in 1980 and got nothing but grief for his trouble:

Also in the game was Niatram, one of the system operators (who can’t spell his name backwards). He decided to loom up on this [newbie] character, follow him around a bit, then kill him. This he repeated several times, gaining plenty of points in the process. Finally, the newcomer was at his wits’ end.

“Who’s this Niatram character?” he asked. “He keeps following me around and killing me!” “Yes, he’s done that to me before,” came the reply. “I think he may be dungeon-generated!” At this point Niatram appeared, and out of despair his victim quit, rather than be killed yet again by this “artificial person.”

Today’s virtual worlds are generally wise enough to prevent this sort of thing by one means or another.

Player agency was another area where MUD was dramatically different from the massively-multiplayer games of today, but in this case the difference was, at least from some points of view, a more positive one. Once ordinary players, or “mortals” in MUD speak, reached a certain level, they became “wizards” and “witches” — known by the unisex term of “wizzes” — who were perhaps better described as gods, given that they were granted a stunning degree of control over The Land. “Wiz mode” was originally simply the debug mode used by Trubshaw and Bartle themselves, but it wound up becoming a key part of the game, Bartle’s answer to the expert player’s question of “Well, what now?”

Becoming a wiz required one to amass 76,800 points without getting killed, no mean feat in the cheerfully genocidal realm of The Land. The powers wiz mode conveyed extended to the point of being able to crash the game at will. Tired of watching wizzes invent ways to do so to prove their cleverness, Bartle actually added the verb “crash” to the wizzes’ vocabulary in order to convey the message that, yes, you have the power to do this; you therefore don’t have to bother inventing more convoluted methods for doing so, like, say, plucking the rain from the sky of two separate rooms and mashing the lot together. Safe in the knowledge that they could crash the game at will, effortlessly, most wizzes did indeed see no reason to bother actually doing so. Which didn’t, of course, prevent all the accidental crashes: it was always a sure sign that someone new had attained wiz status and was experimenting with her powers when the game just kept going down over and over.

Once mastered, though, the wizzes’ powers truly were extraordinary. They could snoop on mortals, watching the commands they typed and what appeared on their screens in response; could move objects from any room to any other room without touching them; could move themselves or other players from any room to any other room; could use a “finger of death” spell to instantly kill any mortal, permanently; could grant instant wiz status to any non-wiz they chose.

It seemingly defies all logic — defies everything we know about human nature — that a game willing to grant some of its players such powers could have sustained itself for a week, much less the years during which MUD ran at the University of Essex. It was all indicative of what a different sort of game MUD really was. Running on a university’s computer, free to access by anyone with the wherewithal to make a connection, MUD was a very different proposition from a commercial game, more a joint creative experiment than a product. Bartle:

MUD is an evolving game, and so indeed it should be. It has been incremented gradually, with new ideas put in to be instantly tested by a horde of willing wizzes, or mortals if it was something that they could use (the various “injury” spells — BLIND, DEAFEN, CRIPPLE, DUMB, and CURE — for example). This is one of the great strengths of doing MUD at a university; it’s all research. If a commercial company were to put up a game riddled with bugs, the players would be justifiably upset when it crashed on them. Here, though, it’s free for them to play and they actually like finding mistakes, because it gets them one over on me (and occasionally gets them some points for their honesty!). And it’s also good because we don’t have to pay people to play-test, either — plenty will do it willingly in their spare time for free!

So there will always be a place for MUDs at universities, simply so that research into them can proceed. Universities can have “programs,” whereas commercial companies must have “products.” Products don’t crash (well, not often!) and they are nice and stable. Programs crash like nobody’s business and you never know from one day to the next whether some terrible new command has been added which you don’t know about, but which someone who does is about to use on you. Products are fun, but they don’t change until everything has been thoroughly tested; programs are exciting in their volatility.

Perhaps there is a place for the “not fully tested” system. Even if I as a player did have to put up with a crash every 20 minutes (MUD needs to be reset once a night on average), I think that experiencing the excitement of seeing things evolving and of being among the first to use the novel commands would make me happy to play the program, not the product. Fortunately, enough people think the same way to make debugging that much easier, and to encourage new additions to make the game even more fun for generations of adventurers to come.

Every rule in the game existed, it seemed, to be exploited; mechanically, the place was a leaky sieve that poor Richard Bartle was constantly rushing around to patch. MUD‘s players were endlessly creative when it came to finding exploits. One of Bartle’s favorite anecdotes involves two players who were each about halfway to wiz status. Deciding they’d had enough incrementalism, they hatched a plan to put themselves over the top. First, one of the players kissed the other some 1400 times in succession to transfer all of his points to her, giving her enough to make wiz. Then the newly minted wiz used her special powers to grant instant wiz status to her helper. In response to that, Bartle had to add a rule that players could only use hugs and kisses to transfer points to those with a smaller point total than their own. Just another day at the office…

For all that exploits were a way of life among The Land’s denizens, the absolute power granted to the wizzes proved not to corrupt absolutely. In fact, just the opposite. For all that there was a definite hierarchy in place among the inhabitants of The Land, for all that tormenting the newbies was regarded as such good sport by virtually everyone, a certain attenuated but real code of fair play which Bartle himself did nothing to institute took hold within MUD. And it was the wizzes, the players with the ability to wreck The Land almost beyond redemption if they chose to do so, who came to regard the code as most sacred. Bartle:

The wizzes were once mortals themselves. Wizzes know all too well what it’s like to be summoned to a cold, dark room and left alone with the word “hehehe” ringing in your ears. They know the disappointment in forging through the swamp for half an hour only to find that someone has swapped the incredibly valuable crown in the centre for a fake one. They’ve felt the pangs of outrage when you’ve been attacked by a souped-up bunny rabbit which took you 15 minutes to kill. In short, they know when to stop.

Wizzes make the game. They rule it, they stamp their personalities on it, and they give mortals something to aim for, a goal, a purpose, something which explains why they’re in there hacking and slaying. If MUD does nothing else for multi-user adventure games, for evolving the concept of a wiz it should always be remembered.

By 1984, 53 players had made wiz status: 40 from England, 5 from Scotland, 4 from Wales, 1 from Ireland, 1 from the United States, 1 from Czechoslovakia(!), 1 from Malaysia(!!). The creative powers granted to them made MUD a self-sustaining community. After Bartle built The Land and made it available, he needed do no more. The place was perfectly capable of evolving without him.

“The people,” Bartle noted, “are the game” of MUD. The sense of shared ownership could make The Land a downright cozy place when the inhabitants took a break from killing one another. There was a bizarre craze for Trivial Pursuit for a while, with wizzes shouting out questions which mortals could answer for in-game rewards. And there was at least one MUD wedding, between Frobozz the Wizard and Kate the Enchantress, with the happy couple taking up honeymoon residence in the coveted “Wizard’s Chamber.” (“What interaction occurred thereafter is unknown,” wrote the journalist covering the story.)

Christmas was always a special time of the year, when the wizzes would institute a strictly enforced ban on player-versus-player combat, scatter the landscape with holly, snowmen, wreaths, and plum puddings, and plant Christmas trees in the forests, where one was now apt to encounter a wandering Santa Claus with his reindeer in lieu of the usual monsters. The wizzes desisted from sporting with the newbies to vicariously enjoy their surprise and delight when they logged on to find The Land transformed into a winter wonderland, complete with snow. (“What’s all this snow?” “I don’t know. I just saw Father Christmas go by, and someone has given me this cracker…”) Players would band together to sing Christmas carols, swigging all the while from a shared bottle of rum and diligently role-playing their resulting intoxication.

But who, you might wonder, were all these people who flocked to The Land every night? Like the CB Simulator fraternity on CompuServe, it was a diverse demographic who enjoyed this glimpse of an online future, ranging from teenage hacker whiz kids like Jeremy San to academics in their forties. Perhaps the most dedicated player of all was Sue, the first woman to make wiz, who slept for just three hours or so each night before MUD went online, then played for the full six hours it was available every morning before heading off to her ordinary office job.

Just as on CB Simulator, some of the other people on MUD who claimed to be women weren’t really women at all. Among this group was one Felicity, who was eventually found to be the avatar of a dude named Mark. (Felicity had the reputation, for what it’s worth, of being the “kindest, most responsible wiz of all time.”) Once Felicity/Mark’s deception was uncovered, players claiming to be women were routinely greeted with suspicion. A favorite tactic was to enlist bona-fide females like Sue to engage the latest suspect into a discussion of, say, dress sizes. Thereby were the imposters generally discovered quite quickly.

A wiz called simply Evil gained the reputation of being the most eccentric of all time — quite an achievement with this group. Bartle:

If you wanted to get to any room from any other, no matter how far away, he could give you the shortest route instantly. This was despite the fact that he laboured under a tremendous disability: east-west dyslexia.

It is for this that Evil is best known. His entire in-the-head map of MUD, and all those he wrote down on paper, were flipped east for west. His misapprehension extended to commands, so if he wanted to go west from the start, which is to the left, he’d think it was to the right, and that the command for going to the right was west. So he’d get it correct, but in the wrong way! So absolutely everything was inverted, in a kind of “Evil through the looking glass”. Indeed, when I finally found out about his error I put a looking glass in MUD to celebrate!

He didn’t realise his mistake for years after he’d made it to wiz, and if people used left/right descriptions instead of west/east, he just thought they were barmy. Only when I drew a map of MUD on a blackboard did he finally discover his gaffe, and to this day he thinks a subtle change in the physics of the universe caused everyone in the world to swap east for west in their heads except for him, who remained unaffected due to his enormous and obvious intelligence…

While MUD‘s personality as a game may have been molded more by the cast of eccentrics who inhabited The Land than by Richard Bartle himself, the latter would always remain by far the most important person associated with the game. MUD was, after all, his baby at the end of the day. Even after finishing his degree, he remained at the University of Essex as an artificial-intelligence researcher, with the ulterior motive of continuing to further the cause of MUD. And indeed, from the standpoint of publicity as from so many others, he continued to prove himself to be its greatest asset. As charming and articulate in person as he was an easy and prolific writer, Bartle was able to attract far more press attention for his odd experiment running in the middle of the night on an academic computer than one might expect. He became a fixture in the British computing press of the 1980s, penning long articles about life in The Land for magazines like Practical Computing and Micro Adventurer. His efforts in this regard have proved a goldmine to modern historians, who have come to recognize in the way that his contemporary peers couldn’t possibly be expected to what a landmark creation this first persistent multi-player virtual world really was. It’s largely Bartle’s old articles that form the basis of this new article of mine. With so much in online-gaming history already lost to the ephemerality of the digital medium, we can be thankful that Bartle was as prolific as he was.

Still, preserving MUD culture for posterity wasn’t Richard Bartle’s main motivation for writing these articles. This academic researcher didn’t want MUD to remain a tiny research project at a second-tier university forever; he had a keen interest in moving it beyond the confines of the University of Essex. Early on he gave copies of the software to universities in Portugal, Sweden, Norway, and Scotland, sparking the transformation of the name MUD from a designation for a specific virtual world to a generic tag applied to all parser-driven textual virtual worlds. Despite the identical mechanics, the people who played each incarnation of the software which Bartle shared so freely gave each version of The Land a distinctive character. The MUDs in Scotland and Norway, for instance, were much more easygoing than the one at the University of Essex; delegations from the former expressed horror at the sheer amount of killing that went on in the latter when they came for a visit.

Bartle had no doubt that MUDs represented a better model for adventure gaming, the direction the entire genre by all rights ought to be going:

Like it or not, in the next few years multiplayer games like MUD are going to become the dominating factor in adventure games. The reason for this is quite simple — MUDS are absolutely fantastic to play! The fact that it’s You against Them, rather than You against It, adds an extra electricity you just can’t experience in a single-player game. If you like adventure games already, MUD will absolutely slay you (often literally!).

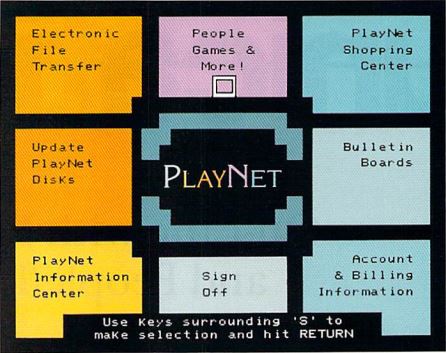

This quote dates from 1984. As it would imply, Bartle by that year had decided the time was right to start commercializing his research experiment. He made a deal to bring MUD to Compunet, a pioneering online service for British owners of Commodore computers, initially funded largely by Commodore’s own innovative United Kingdom branch. The first service of its kind in Britain, Compunet would muddle along for years without ever achieving the same success as QuantumLink, its nearest equivalent in the United States. The tiny staff’s efforts were constantly undone by the sheer expense of telecommunications in Britain, along with a perpetual lack of funding to set up a proper infrastructure for their service; Compunet had, for instance, only a single access number for the entire country, meaning that the vast majority of potential customers had to pay long-distance surcharges just to access it. Although it was available on Compunet for several years, MUD too just never managed to make much of an impression there.

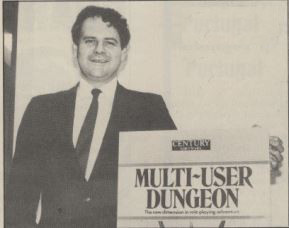

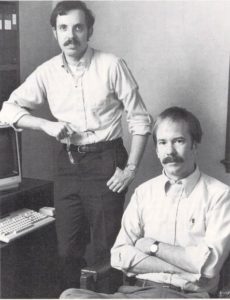

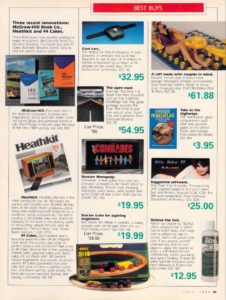

MUSE hosted a gathering of wizzes from the University of Essex MUD to mark the launch of BT MUD. Richard Bartle is the mustachioed fellow standing near the center of the group.

But even as the Compunet MUD was failing to set the world on fire, the game had attracted an important patron. Simon Dally was a longtime gamer, first of tabletop and later of computer games, who had done very well for himself in the book-publishing trade. When he stumbled across MUD for the first time, it was love at first sight. Dally was certain that MUD could change the world, and that it could make him and its creators very rich in the process. He, Bartle, and Roy Trubshaw — the last had recently returned to England from Belgium — formed Multi-User Entertainments, or MUSE (not to be confused with the American software publisher of the same name), to exploit what Dally, even more so than the always-enthusiastic Bartle, believed to be the game’s immense commercial potential. (Trubshaw was more skeptical, and seemed to have agreed to work on MUD once again more for the programming challenge than for its supposed potential to make him rich or to change the world.)

The first project MUSE undertook was to completely rewrite MUD, with Trubshaw once again doing the low-level architecture and Bartle building a world upon these technical underpinnings. Whereas the old MUD had been inextricably tied to the rapidly aging DEC PDP-10, what became known as MUD2 was designed to “run on just about any minicomputer or mainframe in the world” with a minimum of porting; its first incarnation ran on a DEC VAX, a much newer and more powerful piece of kit than the PDP-10. Among many other improvements came the inevitable increases in scale: the old limit of 36 active players on the original MUD became 100 on MUD2, and The Land itself could now be twice as large. As befitted his day job as an artificial-intelligence researcher, Bartle was particularly proud of his new non-player creatures — known as “mobiles” in MUD speak — which were able to talk and trade with human players whilst pursuing goals of their own.

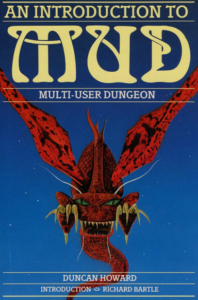

Dally took the new-and-improved MUD to British Telecom and convinced them to make it available as a standalone dial-up service. Playing MUD in its latest commercial incarnation wouldn’t be cheap: it cost £20 to buy the starter pack, plus £2 per hour to play, all on top of the cost of the phone call needed to dial in. With prices like these, the new MUD endeavored to shed its scruffy hacker origins and project an upscale image, beginning with a gala launch at The London Dungeon. Dally used his connections to get a glossy book published: An Introduction to MUD, penned by one Duncan Howard. “I know the BT venture is just the start of something truly enormous,” Dally said. “Our MUD development language — MUDDL — will allow anyone to come to us with an idea for an interactive type of game, and allow us to implement it quickly and cheaply. We are certainly ahead of the States, where MegaWars III, a rather limited interactive game, is going down well, and we have high hopes of selling MUD to the Americans.” Those hopes would come to fruition in remarkably short order.

But in neither country would the game achieve the “truly enormous” status Dally had so confidently predicted. The BT venture proved particularly disappointing. One step Bartle took which may not have been terribly wise was to convince much of the Essex MUD old guard to migrate over to the new game, pulling strings to get them online at reduced or free rates. Thus he imported the old game’s murderous culture and set up an upper class and a lower class of players at a stroke. A writer for Acorn User magazine who surveyed the newbies found that they “don’t much like MUD. They can’t find any treasure, don’t know what to do, and spend their time waiting for the next reset or chatting to each other in the bar. Typical answers to my inquiries included phrases like ‘bored’ or ‘where’s all the T?'”

In addition to the culture clashes, the BT MUD was also a victim, like the Compunet MUD before it, of all the difficulties inherent in telecommunicating in Britain at the time. MUSE could measure their falling status within British Telecom by the people they were assigned as account managers. “It was a gradual decline,” remembers Bartle, “from speaking to board-level directors to being signed off by a youth-opportunities employee.” The next wave of adventure games in Britain the BT MUD most definitely didn’t become. It continued to run for years, but, after the initial publicity blitz puttered out, it existed as little more than another hangout for the same old small in-group it had attracted at the University of Essex. The BT MUD was finally closed down in early 1991, when British Telecom decided they’d had enough of an exercise that had long since become pointless from their perspective.

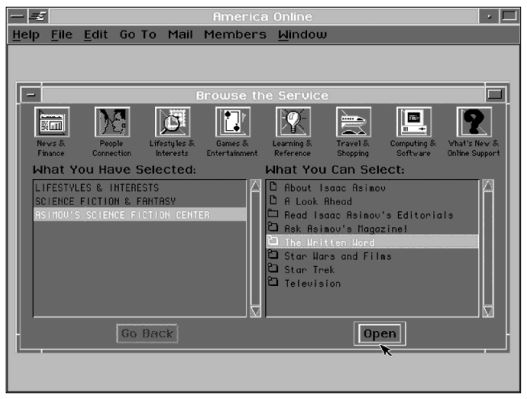

MUSE’s efforts did fare significantly better in the United States. Dally convinced no less of an online player than CompuServe to take the game as an offering on their service. It went up there in the spring of 1986 under the name of British Legends. Perhaps assuming that what had worked for Lord British of Ultima fame could work equally well for them, CompuServe’s marketers emphasized the Anglo connection at every opportunity. They declared over-optimistically that “in England, the game is a sensation,” with “thousands of players.” A couple of years after British Legends made its debut, CompuServe began offering their service in Britain as well as the United States, facilitating the first meetings between large numbers of British and American players in the very same MUD. “I’ve learned more about the United Kingdom from the British players than I learned in all my college courses,” enthused one American player.

Mechanically, British Legends remained unchanged from its other incarnations, including the wizzes running roughshod over the place. Still, it tended to be a less cutthroat world than had the Essex MUD, with more time given over to socializing and cooperating and less to fighting. And of course it was blessed with an initial group of players who were all starting alike from scratch, and thus largely avoided the class conflicts which plagued the BT MUD. It would remain available on CompuServe for more than thirteen years, becoming by far the most long-lived of all the MUD incarnations licensed by MUSE. It was successful enough that virtually all of CompuServe’s competitors either made their own licensing deals with MUSE or came up with an alternative MUD of their own — or, in some cases, did both. Some of the latter were very innovative in their own right. GEnie’s Imagine Nation, for example, strained to be a kinder, gentler sort of MUD, eschewing combat and even goals entirely in favor of providing an environment for its denizens just to hang out and socialize, or to invent their own games in the form of scavenger hunts and trivia contests. In later years MUDs in general would increasingly go in this direction. (See, for instance, the modern interactive-fiction community’s longstanding, beloved IF MUD, where people congregate to play text adventures together, to discuss game design, and just to chitchat rather than to chase one another around with virtual swords.)

Yet the relative commercial success MUDs enjoyed in the United States shouldn’t be overstated. Even British Legends, probably the most popular single MUD incarnation ever, was always a niche product even within that small niche of the public with the money and the interest to access a service like CompuServe in the first place. The online services made MUDs available because they could do so fairly cheaply, and because, once they were up, they tended to produce a self-sustaining community of hardcore players which required virtually no nurturing — that is to say, they required virtually no further financial investment whatsoever, thanks to the self-sustaining genius of wiz mode.

But in the big picture, Richard Bartle and Simon Dally’s mutual passion was destined to be far more influential than it would be profitable. The death of the dream of MUDs as the dominant adventure-game form of the future came in a tragically literal fashion in 1989, when Dally killed himself. It’s impossible to say to what extent his suicide was prompted by his disappointment at the failure of MUD to achieve the world domination he had predicted and to what extent it was a product of the other mental-health issues from which he had apparently been suffering, as manifested in behavior his friends and colleagues later described as “erratic.” There can be no doubt, however, that his death marked the definitive end of the MUD’s flirtation with mainstream prominence.

Any attempt to explain why MUDs remained a niche interest must begin with their textual nature. MUSE had been formed just after the text adventure had reached its commercial peak and was about to enter its long decline, over the course of which it would gradually be replaced on store shelves by the graphic adventure. A game that consisted of nothing but text was doomed to become a harder and harder sell after 1985. But MUDs had their problems even in comparison to single-player text adventures — problems which Richard Bartle was always a bit too eager to overlook. Many players of adventure games loved puzzles, but, as we’ve seen, puzzles didn’t really work all that well in MUDs. Many craved the experience of seeing a story through from beginning to end, knowing all the while that they were the most important character in that story; MUDs couldn’t provide this either. Ask many who had tried to like MUDs, and they’d tell you that they were just too capricious, too unstructured, too difficult to get into, even before you started wrestling with a parser that sometimes seemed willfully determined not to understand you. MUDs had invented the idea of the persistent online virtual world, but the millions and millions of players who would later come to live a good chunk of their lives in such places would have a very different technological window onto them.

The way forward, in commercial terms at least, would be through more structured designs attached to cleaner interfaces, eventually using graphics instead of text wherever possible. While the hardcore who loved MUDs for the very things the casual dabblers hated about them complained — and by no means entirely without justification — that something precious was being lost, game developers would increasingly push in this more accessible direction. Instead of making multi-player text adventures with CRPG elements, they would build their persistent worlds on the framework of the traditional CRPG — full stop.

(Sources: the books MMOs from the Inside Out by Richard Bartle and Grand Thieves and Tomb Raiders: How British Videogames Conquered the World by Magnus Anderson and Rebecca Levene; Byte of December 1980; Micro Adventurer of September 1984, October 1984, November 1984, December 1984, January 1985, February 1985, and March 1985; Practical Computing of June 1982 and December 1983; Popular Computing Weekly of December 20 1984, February 28 1985, and May 23 1985; Commodore Disk User of November 1987; Your Computer of September 1985; Sinclair User of November 1985; Computer and Video Games of November 1985; Commodore User of February 1986; Acorn User of July 1985, October 1985, April 1987, and June 1987; New Computer Express of March 9 1991; Online Today of February 1986, January 1988, and March 1988; The Gamer’s Connection of September/October 1988; Questbusters of October 1989. Online sources include the article “CNET — Moving with the Times” from Commodore Apocalypse and Gamespy’s history of MUDs.

You can still play MUD1 today by telnetting to british-legends.com, port 27750. You can play MUD2 by telnetting to mud2.com, port 27723.)