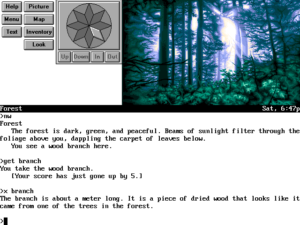

Among the most rewarding hidden gems in Sierra’s voluminous catalog must be the games of the Discovery Series, the company’s brief-lived educational line of the early 1990s. Doubtless because of that dreaded educational label, these games are little-remembered today even by many hardcore Sierra fans, and, unlike most of the better-known Sierra games, have never been reissued in digital-download editions.

In my book, that’s a real shame. For reasons I’ve described at exhaustive length by now in other articles, I’m not a big fan of Sierra’s usual careless approach to adventure-game design, but the games of the Discovery Series stand out for their lack of such staple Sierra traits as dead ends, illogical puzzles, and instant deaths, despite the fact that they were designed and implemented by the very same people who were responsible for the “adult” adventure games. These design teams were, it seems, motivated to show children the mercy they couldn’t be bothered to bestow upon their adult players. While it’s true that even the Discovery games weren’t, as we’ll see, entirely free of regrettable design choices, these forgotten stepchildren ironically hold up far better today than most of their more popular siblings. For that reason, they’re well worth highlighting as part of this ongoing history.

I’ve already written about the Discovery Series’s two Dr. Brain games, creative and often deceptively challenging puzzle collections that can be enjoyed by adults as easily as by children. Today, then, I’d like to complete my coverage. Although some of the other Discovery games were aimed at younger children, and are thus outside the scope of our usual software interests, three others could almost have been sold as regular Sierra adventure games. So, I’ll use this article to look at this trio more closely — the first of which in particular is a true classic, in my opinion the best Sierra adventure of any stripe released during 1992.

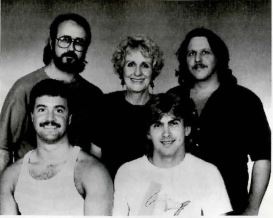

One of the ways in which Sierra stood out in a positive way from their peers was their willingness to employ women in the roles of writer and designer. At a time when almost no one else in the computer-games industry had any women in prominent creative roles, Sierra’s gender balance approached fifty-fifty at times.

Gano Haine, one of these female designers, was also a fine example of what we might call a second-generation adventure designer — someone who had seen the genre evolve from the perspective of a player in the 1980s, and was now ready to make her own mark on it in the 1990s. She took a roundabout route into the industry. A mother and junior-high teacher of fifteen years standing, hers was a prominent voice in the Gamers Forum on CompuServe in the latter 1980s. She wrote extensively there about the good and bad of each game she played. “I don’t think it’s something you do to yourself on purpose,” she said of her adventure-game addiction. “I soon realized that I needed to find a way to make it a profession or I’d starve.” Luckily, Sierra hired her, albeit initially only as an informal consultant. Soon, though, she moved to Oakhurst, California, to become a full-time Sierra game designer. That happened in 1991, just as the Discovery Series was being born.

Everyone among the designers, whether a wizened veteran or a fresh-faced recruit, was given an opportunity to pitch an idea for the new line. The stakes were high because those whose pitches were not accepted would quite probably wind up working in subservient roles on those projects which had been given the green light. Yet Haine was motivated by more than personal ambition when she offered up her idea. One teenage memory that had never left her came to the fore.

I worked a lot in children’s summer camps. There was a beach where we took the children every Wednesday, a beautiful beach, with rocks and glittering sand. I remember once we sat on the rocks and watched a whole school of porpoises jumping in the waves.

Anyway, the next season when we went there, the whole beach was covered with litter. As I walked down to the water with the kids, I looked down, and there was human sewage running across the sand and into the ocean. To see that beautiful place trashed was tremendously painful to me.

Thus was born EcoQuest: an adventure game meant to teach its young players about our precious, fragile natural heritage. After her idea was accepted, Haine was assigned Jane Jensen, a former Hewlett Packard programmer and frustrated novelist who had been hired at almost the same time as her, to work with her as co-designer. This meant that EcoQuest would not only have a female lead designer, but would become the first computer game in history that was the product of an all-female design team.

Thinking, as Sierra always encouraged their designers to do, in terms of an all-new game’s series potential, Haine and Jensen created a young protagonist named Adam. Adam’s father is an ecologist who spends his life traveling the globe dealing with various environment catastrophes, and his lonely son tags along, finding his friends among the animals living in the places they visit.

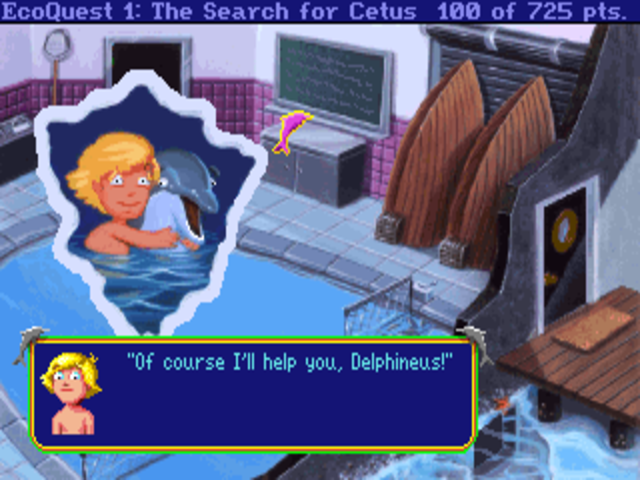

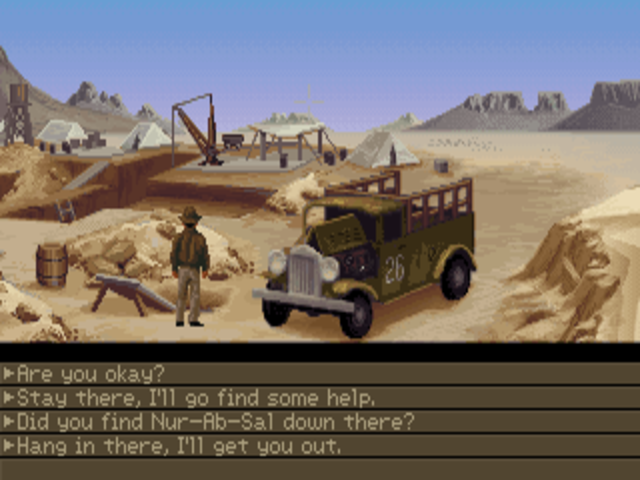

In light of the disturbing memory that had spawned the series, the first game had always been destined to take place in the ocean. Adam gets recruited by one of his anthropomorphic animal friends, a dolphin named Delphineus, to search for Cetus, the great sperm whale whom all of the other undersea creatures look to for guidance, but who’s now gone missing. (One guess which species of bipedal mammal is responsible…) The game was therefore given the subtitle of The Search for Cetus to join the EcoQuest series badge.

Sierra was by no means immune to the allure of the trendy, and certainly there was a whiff of just that to making this game at this time. The first international Earth Day had taken place on April 22, 1990, accompanied by a well-orchestrated media campaign that turned a spotlight — arguably a brighter spotlight than at any earlier moment in history — onto the many environmental catastrophes that were facing our planet even then. This new EcoQuest series was very much of a piece with Earth Day and the many other media initiatives it spawned. Still, the environmental message of EcoQuest isn’t just a gimmick; anthropomorphic sea creatures aside, it’s very much in scientific earnest. Haine and Jensen worked with the Marine Mammal Center of Sausalito, California, to get the science right, and Sierra even agreed to donate a portion of the profits to the same organization.

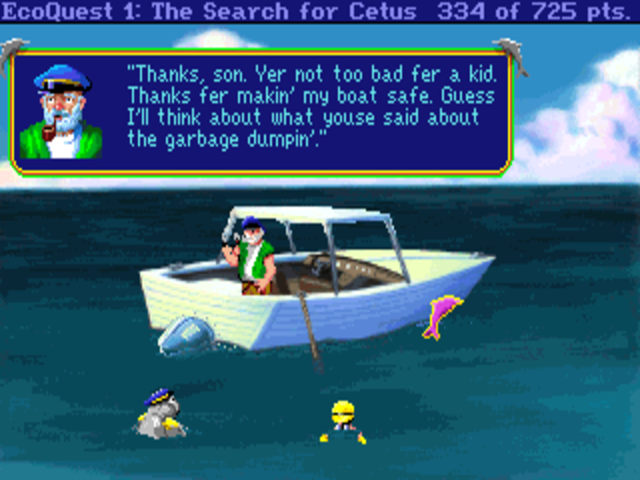

There’s a refreshing sweetness to the game that some might call naivete, an assumption that the most important single factor contributing to the pollution of our oceans is simple ignorance. For example, Adam meets a fishing boat at one point whose propeller lacks a protective cage to prevent it from injuring manatees and other ocean life. He devises a way of making such a cage and explains its importance to the fisherman, who’s horrified to learn the damage his naked propeller had been causing and more than happy to be given this solution. The only glaring exception to the rule of human ignorance rather than malice is the whaling ship that, it turns out, has harpooned poor Cetus.

The message of The Search for Cetus would thus seem to be that, while there are a few bad apples among us, most people want to keep our oceans as pristine as possible and want the enormous variety of species which live in them to be able to survive and thrive. Is this really so very naive? From my experience, at any rate, most people would react just the same as the fisherman in an isolated circumstance like his. It’s the political and financial interests that keep getting in the way, preventing large-scale change by inflaming passions that have little bearing on the practicalities at hand. Said interests are obviously outside the scope of this children’s adventure game, but the same game does serve as a reminder that many things in this world aren’t really so complicated in themselves; they’re complicated only because some among us insist on making them so, often for disingenuous purposes.

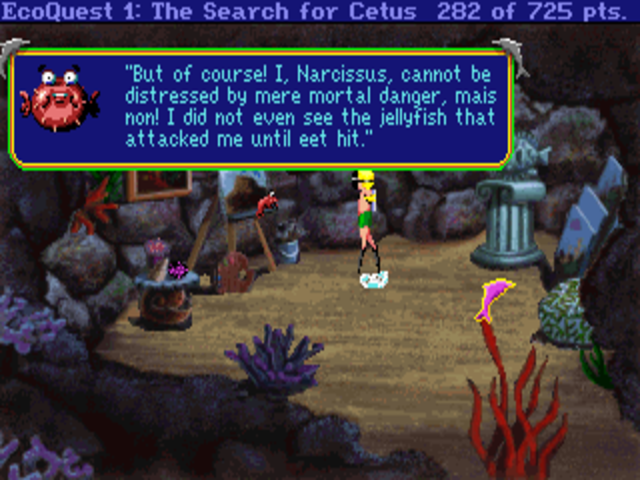

Yet The Search for Cetus is never as preachy as the paragraph I’ve just written. Jane Jensen would later go on to become one of the most famed adventure designers in history through her trilogy of supernatural mysteries starring the reluctant hero Gabriel Knight. The talent for characterization that would make those games so beloved is also present, at least in a nascent form, in The Search for Cetus. From an hysterical hermit crab to a French artiste of a blowfish, the personalities are all a lot of fun. “The characters’ voices and personalities are used to humanize their plight,” said Jensen, “giving a voice to the faceless victims of our carelessness.” Most critically, the characters all feel honestly cute or comic or both; The Search for Cetus never condescends to its audience. This is vitally important to the goal of getting the game’s environmental message across because children can smell adult condescension from a mile away, and it’s guaranteed to make them run screaming.

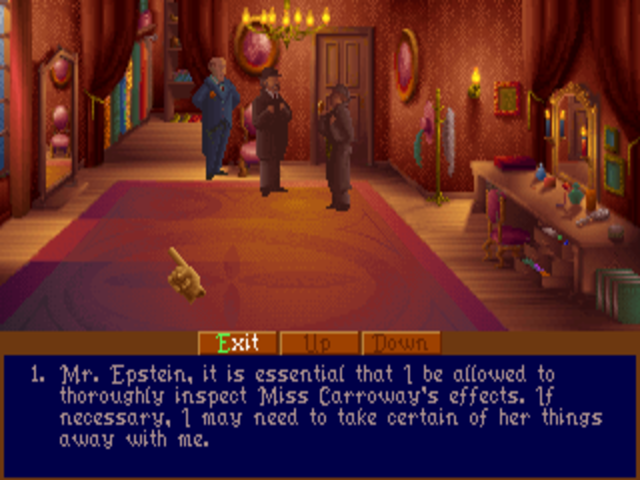

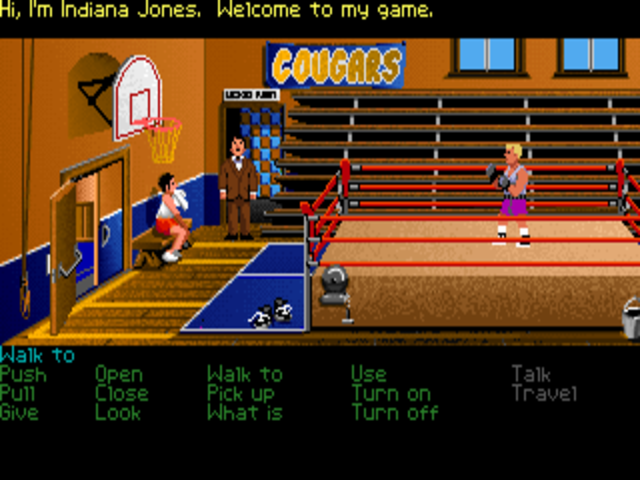

The techniques the game uses to educate in a natural-feeling interactive context are still worthy of study today. For example, a new verb is added to the standard Sierra control panel: “recycle.” This comes to function as a little hidden-object game-within-the-game, as you scan each screen for trash, getting a point for every piece that you recycle. Along the way, you’ll be astonished both by the sheer variety of junk that makes its way into our oceans and the damage it causes: plastic bags suffocate blowfish, organic waste causes algae to grow out of control, plastic six-pack rings entangle swordfish and dolphins, balloons get eaten by turtles, bleach poisons the water, tar and oil kills coral. In the non-linear middle section of the game, you solve a whole series of such problems for the ocean’s inhabitants, learning a great deal about them in the process. You even mark a major chemical spill for cleanup. The game refuses to throw up its hands at the scale of the damage humanity has done; its lesson is that, yes, the damage is immense, but we — and even you, working at the individual level — can do something about it. This may be the most important message of all to take away from The Search for Cetus.

The game isn’t hard by any means, but nor is it trivial. Jane Jensen:

Gano and I are both Sierra players, so when we started to design our first Sierra game, we designed a game that we would want to play. The puzzles in EcoQuest are traditional Sierra adventure-game puzzles, with an ecological and educational slant. You can’t die in the game, but other than that, it’s a real Sierra adventure. Because it is aimed at an older audience, the gameplay isn’t simplified like Mixed-Up Mother Goose or Fairy Tales. The puzzles are challenging, and lots of fun.

Thus the concessions to the children that were expected to become the primary audience take the form not of complete infantilization, but rather a lack of pointless deaths, a lack of unwinnable states, and a number of optional puzzles which score points but aren’t required to finish the game. Many outside Sierra’s rather insular circle of designers, of course, would call all of these things — especially the first two — simply good design, full stop.

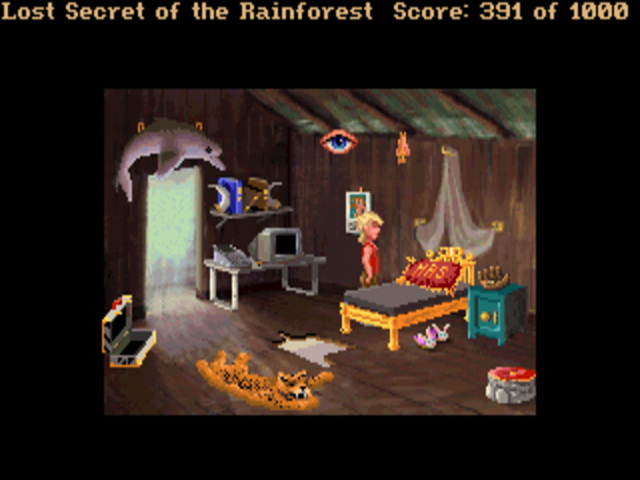

Released in early 1992, The Search for Cetus did well enough that Sierra funded a CD-ROM version with voice acting to supplement the original floppy-based version about a year later. And they funded a further adventure of young Adam as well, which was also released in early 1993. In Lost Secret of the Rainforest, he and his father head for the Amazon, where they confront the bureaucrats, poachers, and clear-cutters that threaten another vital ecosystem’s existence.

With this second game in the series, Sierra clearly opted for not fixing what isn’t broken: all of the educational approaches and program features we remember from the original, from the anthropomorphic animals to the recycling icon, make a return. There’s even a clever new minigame this time around, involving an “ecorder,” a handheld scanner that identifies plants and animals and other things you encounter and provides a bit of information about them. So, in addition to hunting for toxic trash, you’re encouraged to try to find everything in the ecorder’s database as you explore the jungle.

Unfortunately, though, it just doesn’t all come together as well as it did the first time around. Jane Jensen didn’t work on Lost Secret, leaving the entirety of the game in the hands of Gano Haine, who lacked her talent for engaging characters and dialog. She obviously strove mightily, but the results too often come across as labored, unfunny, and/or leaden. (Haine did mention in an interview that, responding to complaints from some quarters that the text in Search for Cetus was too advanced for some children, she made a conscious attempt to simplify the writing in the sequel; this may also have contributed to the effect I’m describing.)

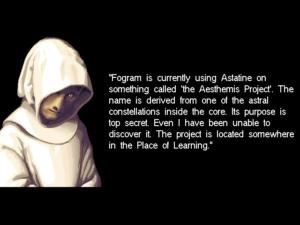

The puzzle design as well is unbalanced, being fairly straightforward until a scene in the middle which seems to have been beamed in from another game entirely. This scene, in which Adam has been captured by a group of poachers and needs to escape, all but requires a walkthrough to complete for players of any age, combining read-the-author’s mind puzzles with the necessity for fiddly, pinpoint-precise clicking and timing. And then, after you clear that hurdle, the game settles back down into the old routine, running on to the end in its old straightforward manner, as if it nothing out of the way had ever happened. It’s deeply strange, and all by itself makes Lost Secret difficult to recommend with anything like the same enthusiasm as its predecessor. It’s not really a bad game on the whole — especially if you go into it forewarned about its one truly bad sequence — but it’s not a great one either.

The poacher named Slaughter has a pink-river dolphin carcass hanging over his door, book stands made from exotic horns, a jaguar-skin rug on his floor, and a footstool made from an elephant’s foot. Laying it on just a bit thick, perhaps?

And on that somewhat disappointing note, the EcoQuest series ended. The science behind the two games still holds up, and the messages they impart about environmental stewardship are more vital than ever. From the modern perspective, the infelicities in the games’ depiction of environmental issues mostly come in their lack of attention to another threat that has become all too clear in the years since they were made: the impact global warming is having on both our oceans and our rain forests. This lack doesn’t, however, invalidate anything that EcoQuest does say about ecological issues. The second game in particular definitely has its flaws, but together the two stand as noble efforts to use the magic of interactivity as a means of engagement with pressing real-world issues — the sort of thing that the games industry, fixated as it always has been on escapist entertainment, hasn’t attempted as much as it perhaps ought to. “Environmental issues are very emotional,” acknowledges Gano Haine, “and you inevitably contact people who have very deep disagreements about those issues.” Yet the EcoQuest series dares to present, in a commonsense but scientifically rigorous way, the impact some of our worst practices are having on our planet, and dares to ask whether we all couldn’t just set politics aside and try to do that little bit more to make the situation better.

In that spirit, I have to note that some of the most inspiring aspects of the EcoQuest story are only tangentially related to the actual games. A proud moment for everyone involved with the series came when Sierra received a letter from a group of kids in faraway Finland, who had played The Search for Cetus and been motivated to organize a cleanup effort at a polluted lake in their neighborhood. Meanwhile the research that went into making the games caused the entire company of Sierra Online to begin taking issues of sustainability more seriously. They started printing everything from game boxes to pay stubs on recycled paper; started reusing their shipping pallets; started using recycled disks; started sorting their trash and sending it to the recycler. They also started investigating the use of water-based instead of chemical-based coatings for their boxes, soybean ink for printing, and fully biodegradable materials for packing. No, they didn’t hesitate to pat themselves on the back for all this in their newsletter (which, for the record, was also printed on recycled paper after EcoQuest) — but, what the hell, they’d earned it.

The words they wrote in their newsletter apply more than ever today: “It’s not always easy, but it’s worth it. Saving the planet isn’t a passing fad. It’s critical, for our own future and for the future of our children.” One can only hope that the games brought some others around to the same point of view — and may even continue to do so today, for those few who discover them moldering away in some archive or other.

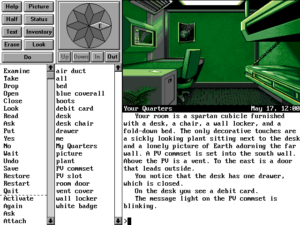

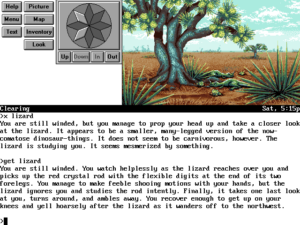

Pepper’s Adventures in Time, the third and final adventure game released as part of the Discovery Series, was a very different proposition from EcoQuest. Its original proposer wasn’t one of Sierra’s regular designers, but rather Bill Davis, the veteran television and film animator who had been brought in at the end of the 1980s to systematize the company’s production processes to suit a new era of greater audiovisual fidelity and exploding budgets. His proposal was for a series called Twisty History, which would teach children about the subject by asking them to protect history as we know it from the depredations wrought by the evil inventor of a time machine. Because Davis wasn’t himself a designer, the first game in the planned series became something of a community effort, a collaboration that included Gano Haine and Jane Jensen as well as Lorelei Shannon and Josh Mandel. (That is, for those tracking gender equality in real time, three female designers and one male.)

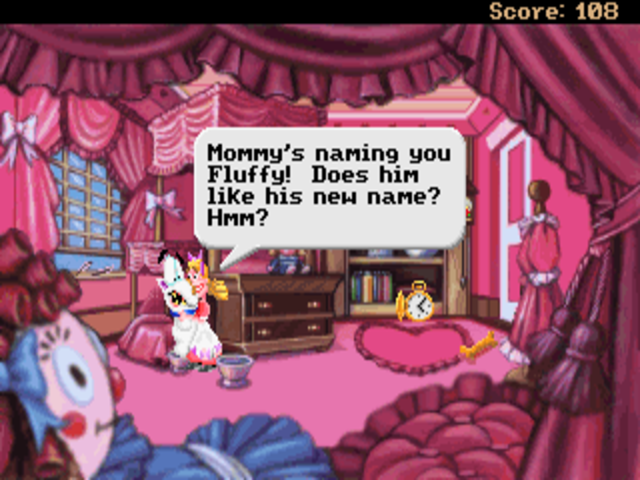

The star of the series, as sketched by Bill Davis and filled in by the design team, is a girl named Pepper Pumpernickel, a spunky little thing who doesn’t take kindly to the opposite sex telling her what she can and can’t do. Her costar is Lockjaw, her pet dog. Davis:

We’d recently lost a dog to leukemia, had gone through an extended period of mourning, and had decided it was time to adopt. So my wife and son headed for our favorite adoption agency, the local animal shelter. They came home with a German shepherd/terrier mix. The terrier turned out to be Staffordshire terrier. For those in the dark, as we were, Staffordshire terrier is synonymous with “pit bull.” Anyway, she turned out to be a lovable little mutt with a bit of an attitude. Thirty pounds of attitude, to be precise. Well, as I was sitting at the drawing board designing characters for Twisty, she shoved her attitude up my behind and into the game proposal.

Lockjaw threatens at times to steal the game from Pepper — as, one senses, he was intended to. The player even gets to control him rather than Pepper from time to time, using his own unique set of doggie verbs, like a nose icon for sniffing, a paw icon for digging, and a mouth icon for eating — or biting. It’s clear that the designers really, really want you to be charmed by their fierce but lovable pooch, but for the most part he is indeed as cute as they want him to be, getting himself and Pepper into all kinds of trouble, only to save the day when the plot calls for it.

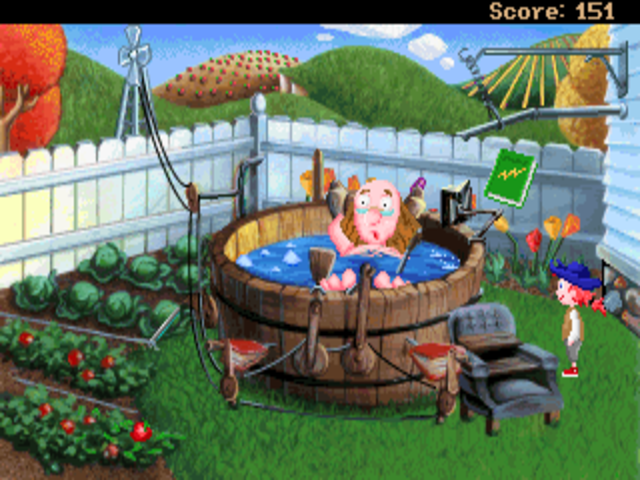

Ben Franklin’s doctrine of sober industriousness has been corrupted into hippie indolence. It’s up to Pepper to right the course of history as we know it.

Otherwise, the theme of this first — and, as it would turn out, only — game in the series is fairly predictable for a work of children’s history written in this one’s time and place. Pepper travels back to “Colonial” times, that semi-mythical pre-Revolutionary War period familiar to every American grade-school student, when Ben Franklin was flying his kite around, Thomas Paine was writing about the rights of the citizen, and the evil British were placing absurd levies on the colonists’ tea supply. (Perish the thought!)

While its cozily traditional depiction of such a well-worn era of history doesn’t feel as urgent or relevant as the environmental issues presented by EcoQuest, the game itself is a lot of fun. The script follows the time-tested cartoon strategy of mixing broad slapstick humor aimed at children with subtler jokes for any adults who might be playing along: referencing Monty Python, poking fun at the tedious professors we’ve all had to endure. Josh Mandel had worked as a standup comedian before coming to Sierra, and his instinct for the punchline combined with Jane Jensen’s talent for memorable characterization can’t help but charm.

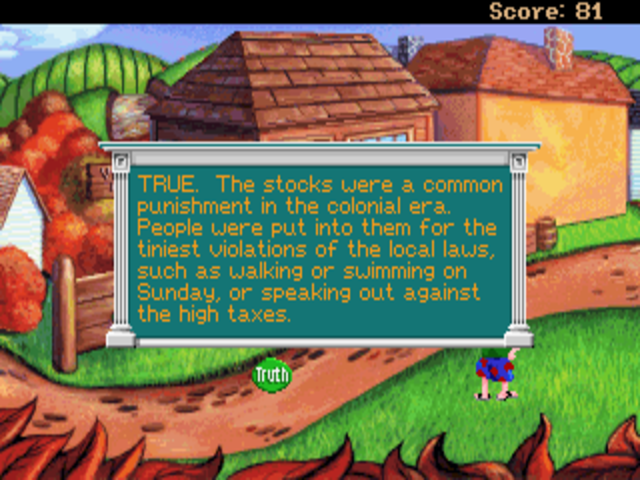

The puzzle design too is pretty solid, with just a couple of places that could have used a bit more guidance for the player and/or a bit more practical thinking-through on the part of the designers. (Someone really should have told the designers that fresh tomatoes and ketchup aren’t remotely the same thing when it comes to making fake blood…) And, once again, the game does a good job of blending the educational elements organically into the whole. This time around, you have a “truth” icon you can use to find out what is cartoon invention and what is historically accurate; the same icon provides more background on the latter. You use what you have (hopefully) learned in this way to try to pass a quiz that’s presented at the end of each chapter, thus turning the study of history into a sort of scavenger hunt that’s more entertaining than one might expect, even for us jaded adults.

What had been planned as the beginning of the Twisty History series was re-badged as the one-off Pepper’s Adventures in Time just before its release in the spring of 1993. This development coincided with the end of the Discovery Series as a whole, only two years after it had begun. Sierra had just acquired a Seattle software house known as Bright Star Technology, who were henceforward to constitute their official educational division. Bright Star appropriated the character of Dr. Brain, but the rest of the budding collection of series and characters that constituted the Discovery lineup were quietly retired, and the designers who had made them returned to games meant strictly to entertain. And so passed into history one of the most refreshing groups of games ever released by Sierra.

(Sources: the book Jane Jensen: Gabriel Knight, Adventure Games, and Hidden Objects by Anastasia Salter; Sierra’s newsletter InterAction of Spring 1992, Fall 1992, Winter 1992, and June 1993; Compute! of January 1993; Questbusters of March 1992; materials in the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play. And my thanks go to Corey Cole, who took the time to answer some questions about this period of Sierra’s history from his perspective as a developer there.

Feel free to download EcoQuest: The Search for Cetus, EcoQuest: Lost Secret of the Rainforest, and Pepper’s Adventures in Time from this site, in a format that will make them as easy as possible to get running using your platform’s version of DOSBox or ScummVM.)