“Mathematics,” wrote the historian of science Carl Benjamin Boyer many years ago, “is as much an aspect of culture as it is a collection of algorithms.” The same might be said about the mathematical algorithms we choose to prioritize — especially in these modern times, when the right set of formulas can be worth many millions of dollars, can be trade secrets as jealously guarded as the recipes for Coca-Cola or McDonald’s Special Sauce.

We can learn much about the tech zeitgeist from those algorithms the conventional wisdom thinks are most valuable. At the very beginning of the 1990s, when “multimedia” was the buzzword of the age and the future of games was believed to lie with “interactive movies” made out of video clips of real actors, the race was on to develop video codecs: libraries of code able to digitize footage from the analog world and compress it to a fraction of its natural size, thereby making it possible to fit a reasonable quantity of it on CDs and hard drives. This was a period when Apple’s QuickTime was regarded as a killer app in itself, when Philips’s ill-fated CD-i console could be delayed for years by the lack of a way to get video to its screen quickly and attractively.

It is a rule in almost all kinds of engineering that, the more specialized a device is, the more efficiently it can perform the tasks that lie within its limited sphere. This rule holds true as much in computing as anywhere else. So, when software proved able to stretch only so far in the face of the limited general-purpose computing power of the day, some started to build their video codecs into specialized hardware add-ons.

Just a few years later, after the zeitgeist in games had shifted, the whole process repeated itself in a different context.

By the middle years of the decade, with the limitations of working with canned video clips becoming all too plain, interactive movies were beginning to look like a severe case of the emperor’s new clothes. The games industry therefore shifted its hopeful gaze to another approach, one that would prove a much more lasting transformation in the way games were made. This 3D Revolution did have one point of similarity with the mooted and then abandoned meeting of Silicon Valley and Hollywood: it too was driven by algorithms, implemented first in software and then in hardware.

It was different, however, in that the entire industry looked to one man to lead it into its algorithmic 3D future. That man’s name was John Carmack.

Whether they happen to be pixel art hand-drawn by human artists or video footage captured by cameras, 2D graphics already exist on disk before they appear on the monitor screen. And therein lies the source of their limitations. Clever programmers can manipulate them to some extent — pixel art generally more so than digitized video — but the possibilities are bounded by the fundamentally static nature of the source material. 3D graphics, however, are literally drawn by the computer. They can go anywhere and do just about anything. For, while 2D graphics are stored as a concrete grid of pixels, 3D graphics are described using only the abstract language of mathematics — a language able to describe not just a scene but an entire world, assuming you have a powerful enough computer running a good enough algorithm.

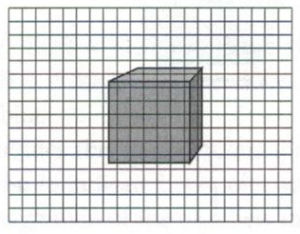

Like so many things that get really complicated really quickly, the basic concepts of 3D graphics are disarmingly simple. The process behind them can be divided into two phases: the modeling phase and the rendering, or rasterization, phase.

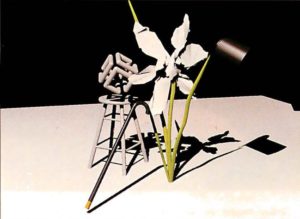

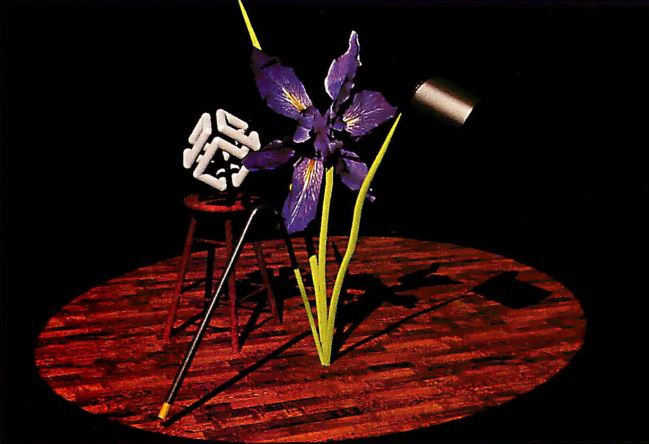

It all begins with simple two-dimensional shapes of the sort we all remember from middle-school geometry, each defined as a collection of points on a plane and straight lines connecting them together. By combining and arranging these two-dimensional shapes, or surfaces, together in three-dimensional space, we can make solids — or, in the language of computerized 3D graphics, objects.

Here we see how 3D objects can be made ever more more complex by building them out of ever more surfaces. The trade-off is that more complex objects require more computing power to render in a timely fashion.

Once we have a collection of objects, we can put them into a world space, wherever we like and at whatever angle of orientation we like. This world space is laid out as a three-dimensional grid, with its point of origin — i.e., the point where X, Y, and Z are all zero — wherever we wish it to be. In addition to our objects, we also place within it a camera — or, if you like, an observer in our world — at whatever position and angle of orientation we wish. At their simplest, 3D graphics require nothing more at the modeling phase.

We sometimes call the second phase the “rasterization” phase in reference to the orderly two-dimensional grid of pixels which make up the image seen on a monitor screen, which in computer-science parlance is known as a raster. The whole point of this rasterization phase, then, is to make our computer’s monitor a window into our imaginary world from the point of view of our imaginary camera. This entails converting said world’s three dimensions back into our two-dimensional raster of pixels, using the rules of perspective that have been understood by human artists since the Renaissance.

We can think of rasterizing as observing a scene through a window screen. Each square in the mesh is one pixel, which can be exactly one color. The whole process of 3D rendering ultimately comes down to figuring out what each of those colors should be.

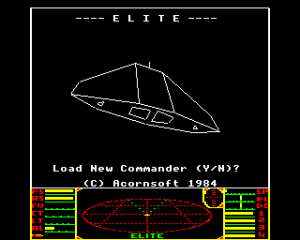

The most basic of all 3D graphics are of the “wire-frame” stripe, which attempt to draw only the lines that form the edges of their surfaces. They were seen fairly frequently on microcomputers as far back as the early 1980s, the most iconic example undoubtedly being the classic 1984 space-trading game Elite.

Even in something as simple as Elite, we can begin to see how 3D graphics blur the lines between a purely presentation-level technology and a full-blown world simulation. When we have one enemy spaceship in our sights in Elite, there might be several others above, behind, or below us, which the 3D engine “knows” about but which we may not. Combined with a physics engine and some player and computer agency in the model world (taking here the form of lasers and thrusters), it provides the raw materials for a game. Small wonder that so many game developers came to see 3D graphics as such a natural fit.

But, for all that those wire frames in Elite might have had their novel charm in their day, programmers realized that the aesthetics of 3D graphics had to get better for them to become a viable proposition over the long haul. This realization touched off an algorithmic arms race that is still ongoing to this day. The obvious first step was to paint in the surfaces of each solid in single blocks of color, as the later versions of Elite that were written for 16-bit rather than 8-bit machines often did. It was an improvement in a way, but it still looked jarringly artificial, even against a spartan star field in outer space.

The next way station on the road to a semi-realistic-looking computer-generated world was light sources of varying strengths, positioned in the world with X, Y, and Z coordinates of their own, casting their illumination and shadows realistically on the objects to be found there.

The final step was to add textures, small pictures that were painted onto surfaces in place of uniform blocks of color; think of the pitted paint job of a tired X-Wing fighter or the camouflage of a Sherman tank. Textures introduced an enormous degree of complication at the rasterization stage; it wasn’t easy for 3D engines to make them look believable from a multitude of different lines of sight. That said, believable lighting was almost as complicated. Textures or lighting, or both, were already the fodder for many an academic thesis before microcomputers even existed.

In the more results-focused milieu of commercial game development, where what was possible was determined largely by which types of microprocessors Intel and Motorola were selling the most of in any given year, programmers were forced to choose between compromised visions of the academic ideal. These broke down into two categories, neatly exemplified by the two most profitable computer games of the 1990s. Those games that followed in one or the other’s footsteps came to be known as the “Myst clones” and the “DOOM clones.” They could hardly have been more dissimilar in personality, yet they were both symbols of a burgeoning 3D revolution.

The Myst clones got their name from a game developed by Cyan Studios and published by Brøderbund in September of 1993, which went on to sell at least 6 million copies as a boxed retail product and quite likely millions more as a pack-in of one description or another. Myst and the many games that copied its approach tended to be, as even their most strident detractors had to admit, rather beautiful to look at. This was because they didn’t attempt to render their 3D imagery in real time; their rendering was instead done beforehand, often on beefy workstation-class machines, then captured as finished rasters of pixels on disk. Given that they worked with graphics that needed to be rendered only once and could be allowed to take hours to do so if necessary, the creators of games like this could pull out all the stops in terms of textures, lighting, and the sheer number and complexity of the 3D solids that made up their worlds.

These games’ disadvantage — a pretty darn massive one in the opinion of many players — was that their scope of interactive potential was as sharply limited in its way as that of all those interactive movies built around canned video clips that the industry was slowly giving up on. They could present their worlds to their players only as a collection of pre-rendered nodes to be jumped between, could do nothing on the fly. These limitations led most of their designers to build their gameplay around set-piece puzzles found in otherwise static, non-interactive environments, which most players soon started to find a bit boring. Although the genre had its contemplative pleasures and its dedicated aficionados who appreciated them, its appeal as anything other than a tech demo — the basis on which the original Myst was primarily sold — turned out to be the very definition of niche, as the publishers of Myst clones belatedly learned to their dismay. The harsh reality became undeniable once Riven, the much-anticipated, sumptuously beautiful sequel to Myst, “only” sold 1.5 million copies when it finally appeared four years after its hallowed predecessor. With the exception only of Titanic: Adventure out of Time, which owed its fluke success to a certain James Cameron movie with which it happened to share a name and a setting, no other game of this style ever cracked half a million in unit sales. The genre has been off the mainstream radar for decades now.

The DOOM clones, on the other hand, have proved a far more enduring fixture of mainstream gaming. They took their name, of course, from the landmark game of first-person carnage which the energetic young men of id Software released just a couple of months after Myst reached store shelves. John Carmack, the mastermind of the DOOM engine, managed to present a dynamic, seamless, apparently 3D world in place of the static nodes of Myst, and managed to do it in real time, even on a fairly plebeian consumer-grade computer. He did so first of all by being a genius programmer, able to squeeze every last drop out of the limited hardware at his disposal. And then, when even that wasn’t enough to get the job done, he threw out feature after feature that the academics whose papers he had pored over insisted was essential for any “real” 3D engine. His motto was, if you can’t get it done honestly, cheat, by hard-coding assumptions about the world into your algorithms and simply not letting the player — or the level designer — violate them. The end result was no Myst-like archetype of beauty in still screenshots. It pasted 2D sprites into its world whenever there wasn’t horsepower enough to do real modeling, had an understanding of light and its properties that is most kindly described as rudimentary, and couldn’t even handle sloping floors or ceilings, or walls that weren’t perfectly vertical. Heck, it didn’t even let you look up or down.

And absolutely none of that mattered. DOOM may have looked a bit crude in freeze-frame, but millions of gamers found it awe-inspiring to behold in motion. Indeed, many of them thought that Carmack’s engine, combined with John Romero and Sandy Petersen’s devious level designs, gave them the most fun they’d ever had sitting behind a computer. This was immersion of a level they’d barely imagined possible, the perfect demonstration of the real potential of 3D graphics — even if it actually was, as John Carmack would be the first to admit, only 2.5D at best. No matter; DOOM felt like real 3D, and that was enough.

A hit game will always attract imitators, and a massive hit will attract legions of them. Accordingly, the market was soon flooded with, if anything, even more DOOM clones than Myst clones, all running in similar 2.5D engines, the product of both intense reverse engineering of DOOM itself and Carmack’s habit of talking freely about how he made the magic happen to pretty much anyone who asked him, no matter how much his colleagues at id begged him not to. “Programming is not a zero-sum game,” he said. “Teaching something to a fellow programmer doesn’t take it away from you. I’m happy to share what I can because I’m in it for the love of programming.” Carmack was elevated to veritable godhood, the prophet on the 3D mountaintop passing down whatever scraps of wisdom he deigned to share with the lesser mortals below.

Seen in retrospect, the DOOM clones are, like the Myst clones, a fairly anonymous lot for the most part, doubling down on transgressive ultra-violence instead of majestic isolation, but equally failing to capture a certain ineffable something that lay beyond the nuts and bolts of their inspiration’s technology. The most important difference between the Myst and DOOM clones came down to the filthy lucre of dollar and unit sales: whereas Myst‘s coattails proved largely illusory, producing few other hits, DOOM‘s were anything but. Most people who had bought Myst, it seemed, were satisfied with that single purchase; people who bought DOOM were left wanting more first-person mayhem, even if it wasn’t quite up to the same standard.

The one DOOM clone that came closest to replacing DOOM itself in the hearts of gamers was known as Duke Nukem 3D. Perhaps that isn’t surprising, given its pedigree: it was a product of 3D Realms, the rebranded incarnation of Scott Miller’s Apogee Software. Whilst trading under the earlier name, Miller had pioneered the episodic shareware model of game distribution, a way of escaping the heavy-handed group-think of the major boxed-game publishers and their tediously high-concept interactive movies in favor of games that were exponentially cheaper to develop, but also rawer, more visceral, more in line with what the teenage and twenty-something males who still constituted the large majority of dedicated gamers were actually jonesing to play. Miller had discovered the young men of id when they were still working for a disk magazine in Shreveport, Louisiana. He had then convinced them to move to his own glossier, better-connected hometown of Dallas, Texas, and distributed their proto-DOOM shooter Wolfenstein 3D to great success. His protégées had elected to strike out on their own when the time came to release DOOM, but it’s fair to say that that game would probably never have come to exist at all if not for their shareware Svengali. And even if it had, it probably wouldn’t have made them so much money; Jay Wilbur, id’s own tireless guerilla marketer, learned most of his tricks from watching Scott Miller.

Still a man with a keen sense of what his customers really wanted, Miller re-branded Apogee as 3D Realms as a way of signifying its continuing relevance amidst the 3D revolution that took the games industry by storm after DOOM. Then he, his junior partner George Broussard, and 3D Realms’s technical mastermind Ken Silverman set about making a DOOM-like engine of their own, known as Build, which they could sell to other developers who wanted to get up and running quickly. And they used the same engine to make a game of their own, which would turn out to be the most memorable of all those built with Build.

Duke Nukem 3D‘s secret weapon was one of the few boxes in the rubric of mainstream gaming success that DOOM had failed to tick off: a memorable character to serve as both star and mascot. First conceived several years earlier for a pair of Apogee 2D platformers, Duke Nukem was Joseph Lieberman’s worst nightmare, an unrepentant gangster with equally insatiable appetites for bombs and boobies, a fellow who “thinks the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms is a convenience store,” as his advertising trumpeted. His latest game combined some of the best, tightest level design yet seen outside of DOOM with a festival of adolescent transgression, from toilet water that served as health potions to strippers who would flash their pixelated breasts at you for the price of a dollar bill. The whole thing was topped off with the truly over-the-top quips of Duke himself: “I’m gonna rip off your head and shit down your neck!”; “Your face? Your ass? What’s the difference?” It was an unbeatable combination, proof positive that Miller’s ability to read his market was undimmed. Released in January of 1996, relatively late in the day for this generation of 3D — or rather 2.5D — technology, Duke Nukem 3D became by some reports the best-selling single computer game of that entire year. It is still remembered with warm nostalgia today by countless middle-aged men who would never want their own children to play a game like this. And so the cycle of life continues…

Duke Nukem 3D was a triumph of design and attitude rather than technology; in keeping with most of the DOOM clones, the Build engine’s technical innovations over its inspiration were fairly modest. John Carmack scoffed that his old friends’ creation looked like it was “held together with bubble gum.”

The game that did push the technology envelope farthest, albeit without quite managing to escape the ghetto of the DOOM clones, was also a sign in another way of how quickly DOOM was changing the industry: rather than stemming from scruffy veterans of the shareware scene like id and 3D Realms, it came from the heart of the industry’s old-money establishment — from no less respectable and well-financed an entity than George Lucas’s very own games studio.

LucasArts’s Dark Forces was a shooter set in the Star Wars universe, which disappointed everyone right out of the gate with the news that it was not going to let you fight with a light saber. The developers had taken a hard look at it, they said, but concluded in the end that it just wasn’t possible to pull off satisfactorily within the hardware specifications they had to meet. This failing was especially ironic in light of the fact that they had chosen to name their new 2.5D engine “Jedi.” But they partially atoned for it by making the Jedi engine capable of hosting unprecedentedly enormous levels — not just horizontally so, but vertically as well. Dark Forces was full of yawning drop-offs and cavernous open spaces, the likes which you never saw in DOOM — or Duke Nukem 3D, for that matter, despite its release date of almost a year after Dark Forces. Even more importantly, Dark Forces felt like Star Wars, right from the moment that John Williams’s stirring theme song played over stage-setting text which scrolled away into the frame rather than across it. Although they weren’t allowed to make any of the movies’ characters their game’s star, LucasArts created a serviceable if slightly generic stand-in named Kyle Katarn, then sent him off on vertigo-inducing chases through huge levels stuffed to the gills with storm troopers in urgent need of remedial gunnery training, just like in the movies. Although Dark Forces toned down the violence that so many other DOOM clones were making such a selling point out of — there was no blood whatsoever on display here, just as there had not been in the movies — it compensated by giving gamers the chance to live out some of their most treasured childhood media memories, at a time when there were no new non-interactive Star Wars experiences to be had.

Unfortunately, LucasArts’s design instincts weren’t quite on a par with their presentation and technology. Dark Forces‘s levels were horribly confusing, providing little guidance about what to do or where to go in spaces whose sheer three-dimensional size and scope made the two-dimensional auto-map all but useless. Almost everyone who goes back to play the game today tends to agree that it just isn’t as much fun as it ought to be. At the time, though, the Star Wars connection and its technical innovations were enough to make Dark Forces a hit almost the equal of DOOM and Duke Nukem 3D. Even John Carmack made a point of praising LucasArts for what they had managed to pull off on hardware not much better than that demanded by DOOM.

Yet everyone seemed to be waiting on Carmack himself, the industry’s anointed Master of 3D Algorithms, to initiate the real technological paradigm shift. It was obvious what that must entail: an actual, totally non-fake rendered-on-the-fly first-person 3D engine, without all of the compromises that had marked DOOM and its imitators. Such engines weren’t entirely unheard of; the Boston studio Looking Glass Technologies had been working with them for five years, employing them in such innovative, immersive games as Ultima Underworld and System Shock. But those games were qualitatively different from DOOM and its clones: slower, more complex, more cerebral. The mainstream wanted a game that played just as quickly and violently and viscerally as DOOM, but that did it in uncompromising real 3D. With computers getting faster every year and with a genius like John Carmack to hand, it ought to be possible.

And so Carmack duly went to work on just such an engine, for a game that was to be called Quake. His ever-excitable level designer John Romero, who had the looks and personality to be the rock star gaming had been craving for years, was all in with bells on. “The next game is going to blow DOOM all to hell,” he told his legions of adoring fans. “DOOM totally sucks in comparison to our next game! Quake is going to be a bigger step over DOOM than DOOM was over Wolf 3D.” Drunk on success and adulation, he said that Quake would be more than just a game: “It will be a movement.” (Whatever that meant!) The drumbeat of excitement building outside of id almost seemed to justify his hyperbole; from all the way across the Atlantic, the British magazine PC Zone declared that the upcoming Quake would be “the most important PC game ever made.” The soundtrack alone was to be a significant milestone in the incorporation of gaming into mainstream pop culture, being the work of Trent Reznor and his enormously popular industrial-rock band Nine Inch Nails. Such a collaboration would have been unthinkable just a few years earlier.

While Romero was enjoying life as gaming’s own preeminent rock star and waiting for Carmack to get far enough along on the Quake engine to give him something to do, Carmack was living like a monk, working from 4 PM to 4 AM every day. In another sign of just how quickly id had moved up in the world, he had found himself an unexpectedly well-credentialed programming partner. Michael Abrash was one of the establishment’s star programmers, who had written a ton of magazine articles and two highly regarded technical tomes on assembly-language and graphics programming and was now a part of Microsoft’s Windows NT team. When Carmack, who had cut his teeth on Abrash’s writings, invited him out of the blue to come to Dallas and do Quake with him, Bill Gates himself tried to dissuade his employee. “You might not like it down there,” he warned. Abrash was, after all, pushing 40, a staid sort with an almost academic demeanor, while id was a nest of hyperactive arrested adolescence on a permanent sugar high. But he went anyway, because he was pretty sure Carmack was a genius, and because Carmack seemed to Abrash a bit lonely, working all night every night with only his computer for company. Abrash thought he saw in Quake a first glimmer of a new form of virtual existence that companies like Meta are still chasing eagerly today: “a pretty complicated, online, networked universe,” all in glorious embodied 3D. “We do Quake, other companies do other games, people start building worlds with our format and engine and tools, and these worlds can be glommed together via doorways from one to another. To me this sounds like a recipe for the first real cyberspace, which I believe will happen the way a real space station or habitat probably would — by accretion.”

He may not have come down if he had known precisely what he was getting into; he would later compare making Quake to “being strapped onto a rocket during takeoff in the middle of a hurricane.” The project proved a tumultuous, exhausting struggle that very nearly broke id as a cohesive company, even as the money from DOOM was continuing to roll in. (id’s annual revenues reached $15.6 million in 1995, a very impressive figure for what was still a relatively tiny company, with a staff numbering only a few dozen.)

Romero envisioned a game that would be as innovative in terms of gameplay as technology, that would be built largely around sword-fighting and other forms of hand-to-hand combat rather than gun play — the same style of combat that LucasArts had decided was too impractical for Dark Forces. Some of his early descriptions make Quake sound more like a full-fledged CRPG in the offing than another straightforward action game. But it just wouldn’t come together, according to some of Romero’s colleagues because he failed to communicate his expectations to them, rather leading them to suspect that even he wasn’t quite sure what he was trying to make.

Carmack finally stepped in and ordered his design team to make Quake essentially a more graphically impressive DOOM. Romero accepted the decision outwardly, but seethed inwardly at this breach of longstanding id etiquette; Carmack had always made the engines, then given Romero free rein to turn them into games. Romero largely checked out, opening a door that ambitious newcomers like American McGee and Tim Willits, who had come up through the thriving DOOM modding community, didn’t hesitate to push through. The offices of id had always been as hyper-competitive as a DOOM deathmatch, but now the atmosphere was becoming a toxic stew of buried resentments.

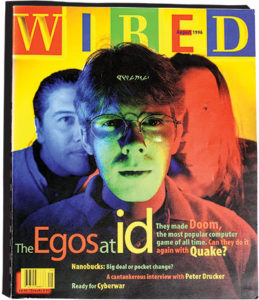

In a misguided attempt to fix the bad vibes, Carmack, whose understanding of human nature was as shallow as his understanding of computer graphics was deep, announced one day that he had ordered a construction crew in to knock down all of the walls, so that everybody could work together from a single “war room.” One for all and all for one, and all that. The offices of the most profitable games studio in the world were transformed into a dystopian setting perfect for a DOOM clone, as described by a wide-eyed reporter from Wired magazine who came for a visit: “a maze of drywall and plastic sheeting, with plaster dust everywhere, loose acoustic tiles, and cables dangling from the ceiling. Almost every item not directly related to the completion of Quake was gone. The only privacy to be found was between the padded earpieces of headphones.”

Wired magazine’s August 1996 cover, showing John Carmack flanked by John Romero and Adrian Carmack, marked the end of an era. By the time it appeared on newsstands, Romero had already been fired.

Needless to say, it didn’t have the effect Carmack had hoped for. In his book-length history of id’s early life and times, journalist David Kushner paints a jittery, unnerving picture of the final months of Quake‘s development: they “became a blur of silent and intense all-nighters, punctuated by the occasional crash of a keyboard against a wall. The construction crew had turned the office into a heap. The guys were taking their frustrations out by hurling computer parts into the drywall like knives.” Michael Abrash is more succinct: “A month before shipping, we were sick to death of working on Quake.” And level designer Sandy Petersen, the old man of the group, who did his best to keep his head down and stay out of the intra-office cold war, is even more so: “[Quake] was not fun to do.”

Quake was finally finished in June of 1996. It would prove a transitional game in more ways than one, caught between where games had recently been and where they were going. Still staying true to that odd spirit of hacker idealism that coexisted with his lust for ever faster Ferraris, Carmack insisted that Quake be made available as shareware, so that people could try it out before plunking down its full price. The game accordingly got a confusing, staggered release, much to the chagrin of its official publisher GT Interactive. To kick things off, the first eight levels went up online. Shortly after, there appeared in stores a $10 CD of the full game that had to be unlocked by paying id an additional $50 in order to play beyond the eighth level. Only after that, in August of 1996, did the game appear in a conventional retail edition.

Predictably enough, it all turned into a bit of a fiasco. Crackers quickly reverse-engineered the algorithms used for generating the unlocking codes, which were markedly less sophisticated than the ones used to generate the 3D graphics on the disc. As a result, hundreds of thousands of people were able to get the entirety of the most hotly anticipated game of the year for $10. Meanwhile even many of those unwilling or unable to crack their shareware copies decided that eight levels was enough for them, especially given that the unregistered version could be used for multiplayer deathmatches. Carmack’s misplaced idealism cost id and GT Interactive millions, poisoning relations between them; the two companies soon parted ways.

So, the era of shareware as an underground pipeline of cutting-edge games came to an end with Quake. From now on, id would concentrate on boxed games selling for full price, as would all of their fellow survivors from that wild and woolly time. Gaming’s underground had become its establishment.

But its distribution model wasn’t the only sense in which Quake was as much a throwback as a step forward. It held fast as well to Carmack’s disinterest in the fictional context of id’s games, as illustrated by his famous claim that the story behind a game was no more important than the story behind a porn movie. It would be blatantly incorrect to claim that the DOOM clones which flooded the market between 1994 and 1996 represented some great exploding of the potential of interactive narrative, but they had begun to show some interest, if not precisely in elaborate set-piece storytelling in the way of adventure games, at least in the appeal of setting and texture. Dark Forces had been a pioneer in this respect, what with its between-levels cut scenes, its relatively fleshed-out main character, and most of all its environments that really did look and feel like the Star Wars films, from their brutalist architecture to John Williams’s unmistakable score. Even Duke Nukem 3D had the character of Duke, plus a distinctively seedy, neon-soaked post-apocalyptic Los Angeles for him to run around in. No one would accuse it of being an overly mature aesthetic vision, but it certainly was a unified one.

Quake, on the other hand, displayed all the signs of its fractious process of creation, of half a dozen wayward designers all pulling in different directions. From a central hub, you took “slipgates” into alternate dimensions that contained a little bit of everything on the designers’ not-overly-discriminating pop-culture radar, from zombie flicks to Dungeons & Dragons, from Jaws to H.P. Lovecraft, from The Terminator to heavy-metal music, and so wound up not making much of a distinct impression at all.

Most creative works are stamped with the mood of the people who created them, no matter how hard the project managers try to separate the art from the artists. With its color palette dominated by shocks of orange and red, DOOM had almost literally burst off the monitor screen with the edgy joie de vivre of a group of young men whom nobody had expected to amount to much of anything, who suddenly found themselves on the verge of remaking the business of games in their own unkempt image. Quake felt tired by contrast. Even its attempts to blow past the barriers of good taste seemed more obligatory than inspired; the Satanic symbolism, elaborate torture devices, severed heads, and other forms of gore were outdone by other games that were already pushing the envelope even further. This game felt almost somber — not an emotion anyone had ever before associated with id. Its levels were slower and emptier than those of DOOM, with a color palette full of mournful browns and other earth tones. Even the much-vaunted soundtrack wound up rather underwhelming. It was bereft of the melodic hooks that had made Nine Inch Nails’s previous output more palatable for radio listeners than that of most other “extreme” bands; it was more an exercise in sound design than music composition. One couldn’t help but suspect that Trent Reznor had held back all of his good material for his band’s next real record.

At its worst, Quake felt like a tech demo waiting for someone to turn it into an actual game, proving that John Carmack needed John Romero as badly as Romero needed him. But that once-fruitful relationship was never to be rehabilitated: Carmack fired Romero within days of finishing Quake. The two would never work together again.

It was truly the end of an era at id. Sandy Petersen was soon let go as well, Michael Abrash went back to the comfortable bosom of Microsoft, and Jay Wilbur quit for the best of all possible reasons: because his son asked him, “How come all the other daddies go to the baseball games and you never do?” All of them left as exhausted as Quake looks and feels.

Of course, there was nary a hint of Quake‘s infelicities to be found in the press coverage that greeted its release. Even more so than most media industries, the games industry has always run on enthusiasm, and it had no desire at this particular juncture to eat its own by pointing out the flaws in the most important PC game ever made. The coverage in the magazines was marked by a cloying fan-boy fawning that was becoming ever more sadly prominent in gamer culture. “We are not even worthy to lick your toenails free of grit and fluffy sock detritus,” PC Zone wrote in a public letter to id. “We genuflect deeply and offer our bare chests for you to stab with a pair of scissors.” (Eww! A sense of proportion is as badly lacking as a sense of self-respect…) Even the usually sober-minded (by gaming-journalism standards) Computer Gaming World got a little bit creepy: “Describing Quake is like talking about sex. It must be experienced to be fully appreciated.”

Still, I would be a poor historian indeed if I called all the hyperbole of 1996 entirely unjustified. The fact is that the passage of time has tended to emphasize Quake‘s weaknesses, which are mostly in the realm of design and aesthetics, whilst obscuring its contemporary strengths, which were in the realm of technology. Although not quite the first game to graft a true 3D engine onto ultra-fast-action gameplay — Interplay’s Descent beat it to the market by more than a year — it certainly did so more flexibly and credibly than anything else to date, even if Carmack still wasn’t above cheating a bit when push came to shove. (By no means is the Quake engine entirely free of tricksy 2D sprites in places where proper 3D models are just too expensive to render.)

Nevertheless, it’s difficult to fully convey today just how revolutionary the granular details of Quake seemed in 1996: the way you could look up and down and all around you with complete freedom; the way its physics engine made guns kick so that you could almost feel it in your mouse hand; the way you could dive into water and experience the visceral sensation of actually swimming; the way the wood paneling of its walls glinted realistically under the overhead lighting. Such things are commonplace today, but Quake paved the way. Most of the complaints I’ve raised about it could be mitigated by the simple expedient of not even bothering with the lackluster single-player campaign, of just playing it with your mates in deathmatch.

But even if you preferred to play alone, Quake was a sign of better things to come. “It goes beyond the game and more into the engine and the possibilities,” says Rob Smith, who watched the Quake mania come and go as the editor of PC Gamer magazine. “Quake presented options to countless designers. The game itself doesn’t make many ‘all-time’ lists, but its impact [was] as a game changer for 3D gaming, [an] engine that allowed other game makers to express themselves.” For with the industry’s Master of 3D Algorithms John Carmack having shown what was possible and talking as freely as ever about how he had achieved it, with Michael Abrash soon to write an entire book about how he and Carmack had made the magic happen, more games of this type, ready and able to harness the technology of true 3D to more exciting designs, couldn’t be far behind. “We’ve pretty much decided that our niche is in first-person futuristic action games,” said John Carmack. “We stumble when we get away from the techno stuff.” The industry was settling into a model that would remain in place for years to come: id would show what was possible with the technology of 3D graphics, then leave it to other developers to bend it in more interesting directions.

Soon enough, then, titles like Jedi Knight and Half-Life would push the genre once known as DOOM clones, now trading under the more sustainable name of the first-person shooter, in more sophisticated directions in terms of storytelling and atmosphere, without losing the essence of what made their progenitors so much fun. They will doubtless feature in future articles.

Next time, however, I want to continue to focus on the technology, as we turn to another way in which Quake was a rough draft for a better gaming future: months after its initial release, it became one of the first games to display the potential of hardware acceleration for 3D graphics, marking the beginning of a whole new segment of the microcomputer industry, one worth many billions of dollars today.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

(Sources: the books Rocket Jump: Quake and the Golden Age of First-Person Shooters by David L. Craddock, The Graphics Programming Black Book by Michael Abrash, Masters of DOOM: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture by David Kushner, Dungeons and Dreamers: The Rise of Computer Game Culture from Geek to Chic by Brad King and John Borland, Principles of Three-Dimensional Computer Animation by Michael O’Rourke, and Computer Graphics from Scratch: A Programmer’s Introduction by Gabriel Gambetta. PC Zone of May 1996; Computer Gaming World of July 1996 and October 1996; Wired of August 1996 and January 2010. Online sources include Michael Abrash’s “Ramblings in Realtime” for Blue’s News.

Quake is available as a digital purchase at GOG.com, as is Star Wars: Dark Forces. Duke Nukem 3D can be found on Steam.)