Licensed games are often dismissed as supremely cynical cash grabs. And for the most part, this judgment is correct: the majority of them are indeed dispiriting affairs.

Licensed games are often dismissed as supremely cynical cash grabs. And for the most part, this judgment is correct: the majority of them are indeed dispiriting affairs.

But no thing in life is all one thing. Take, for instance, the story of Legend Entertainment, which upends all of our prejudices about the licensing racket. Rather than being some evil marketing genius’s idea for maximizing revenue, Legend’s reputation as a peddler primarily of licensed product arose all but accidentally, and at least in the beginning involved very little cynicism at all. It all stems from 1991, when Legend co-founder Mike Verdu decided that he’d really, really like to write a game set in the universe of Gateway, a series of science-fiction novels by Frederick Pohl which he happened to love for reasons pure as the driven snow. When that game was well-received, Legend designer Michael Lindner piped up to say that he would like to make an adaptation of his favorite fantasy series, the Xanth novels of Piers Anthony. And when that too went well, Glen Dahlgren asked for a license to adapt Death Gate, another series of fantasy novels, these ones by Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman. It was all quite shockingly organic — just like one of the press releases put out by one of the other makers of licensed games, the kind that claim that they were actually passionate about Brand X since long before they were given a chance to make a game out of it. In this case, though, it’s the truth.

Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman were among a new group of authors who began reaching bookstores shelves in the 1980s with novels that had begun as games; thus there was a certain poetic symmetry in Legend eventually completing the circle. Indeed, Weis and Hickman had at least as much impact on gaming writ large over the course of their careers as they did on the state of the art of the fantasy novel.

It all began for Tracy Hickman, as it did for so many others, with tabletop Dungeons & Dragons. He was introduced to the game by his fiancée Laura Curtis in the late 1970s, when the two were starving university students in their home town of Salt Lake City, Utah. After getting married and starting a family, the couple looked for a way to justify their hobby when they couldn’t even afford “church shoes” for their two young children. (Like a surprising number of significant figures in gaming history, they were and remain devout Mormons.) So, they founded DayStar West Media to publish two pre-written Dungeons & Dragons “adventure modules.” These sold in fairly minuscule numbers, but provided an entrée to TSR, the maker of the game. In 1982, TSR offered Tracy Hickman a job as an in-house designer. And so the couple piled their children and all the luggage that would fit into the back of their battered old Volkswagen Rabbit and set off for Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, the tabletop RPG scene’s Mecca.

Tracy has since said many times that the idea for Dragonlance, the Hickmans’ master stroke in the fields of both games and books, was born on that long drive. They’d been sent a copy of a marketing study TSR had commissioned, which said that, as Tracy remembers: “1) Dungeons & Dragons is your core product. 2) You have lots of dungeons. 3) You need more dragons.” Ergo, Dragonlance would be a series of adventure modules, each revolving around a different type of dragon.

But its short-term goal of injecting more dragons into the mix has little to do with Dragonlance‘s ultimate importance. The Hickmans conceived it as a series of adventures which would be, as tabletop-gaming historian Shannon Applecline puts it, “plot-oriented” rather than “location-based.” Instead of engaging in the mere tactical challenge of clearing a dungeon of monsters and traps and looting its contents, players would get to live out a complicated epic story worthy of Tolkien himself, set in a brand new, richly detailed fantasy world.

Dragonlance evolved into one of the most ambitious projects TSR ever undertook, one that remains to this day an enduring icon of its hobby. A groundbreaking trans-media experience at a time when such things were much rarer than they’ve become today, its story filled twelve adventure modules, supported by numerous source books — and, most importantly for our purposes, by a trilogy of thick novels which walked its readers through the modules. TSR’s management was first inclined to hire a “real” author to write them, but when the initial pool of applicants proved underwhelming they agreed to let Tracy Hickman and another staffer named Margaret Weis have the assignment. (The important contributions of Laura Hickman — née Laura Curtis — not only in the beginning stages of the project but throughout its duration, went sadly uncredited.)

Dragons of Autumn Twilight, the first volume of the Dragonlance Chronicles, appeared in late 1984. It wasn’t quite at the level of Tolkien; you could almost hear the dice rolling behind the scenes during its lovingly detailed round-by-round descriptions of Dungeons & Dragons combat. Still, it offered up a fast-paced story with appealing characters, and for many or most of its readers the Dungeons & Dragons-ness of the whole affair was actually a feature rather than a bug. It launched TSR into a whole new field of publishing, one that would eventually become more profitable than the games which continued to inform the novels so intimately.

Weis and Hickman, meanwhile, saw their names suddenly at the top of genre-fiction bestseller lists. Almost overnight, the two heretofore obscure game designers became household names among fans of fantasy fiction, bankable enough to be sought after by the old guard of American publishing. They stuck with TSR long enough to write a second, standalone trilogy of Dragonlance novels, but then departed the games industry entirely for more lucrative climes, leaving others there — perhaps most notably the company White Wolf, with their World of Darkness series of Gothic-horror RPGs — to build upon the storytelling revolution they had fostered.

After signing with the Random House imprint of Bantam Books, Weis and Hickman churned out the paperbacks at the steady pace of a novel every six to nine months: first came a Darksword trilogy, then a Rose of the Prophet trilogy. And then, beginning in 1990, came the seven-book Death Gate Cycle.

Like so many fantasy novels, the Death Gate books are most of all an exercise in world-building, and so your level of enjoyment of them must ultimately be determined by your level of interest in their elaborate castles in the air. As my regular readers know all too well by now, I haven’t been part of that target market for a long time. Nevertheless, here’s the capsule version:

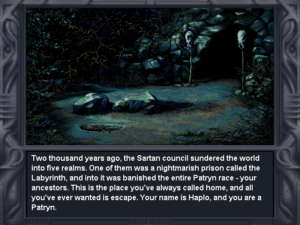

The books involve two races of ultra-advanced beings, known as the Patryns and Sartans, who inhabit the far future of what would appear to be our own planet Earth. Long before the main story of the novels begins, these two races went to war with one another. The Sartans won the war, whereupon they placed the remaining Patryns in an inter-dimensional prison known as the Labyrinth. For rather convoluted reasons, they then sundered the Earth into four separate worlds, each based upon one of the Aristotelian elements — air, water, earth, and fire — and each inhabited mostly by less godly races, whom the Patryns and Sartans traditionally call the Mensch. So much for the backstory. The books proper describe how the Patryns and Sartans finally reconcile and heal their shattered realm. Weis and Hickman were just publishing the fifth of the seven books when Glen Dahlgren over at Legend decided that he’d like to make a game out of them.

Dahlgren had originally been hired to work at Legend as an assistant programmer. But, as was typical of most employees of the tiny company, his responsibilities bloomed in all sorts of unexpected directions after he arrived there. A talent for music led him to become Legend’s in-house sound man, responsible for soundtracks and sound effects alike. A talent for organization led him to become Legend’s quality-control man, overseeing a far-flung network of outside testers. And then he was selected to become one of the three men who put together Gateway, a project consciously engineered by Bob Bates, who had co-founded Legend alongside Mike Verdu, as a boot camp for training up new designers. After that, Dahlgren did half of the design work on Gateway 2, before being given permission to make his own game from start to finish; that game became Death Gate. Bates and Verdu put an enormous amount of faith in him — the sort of faith which one usually only sees manifested at small, young companies like this one, where bureaucracy is minimal and second-guessing rare. Whether or not Dalhgren realized it at the time, his bosses gave him a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Of course, Legend had to secure the license before anything else could happen. Fortunately for everyone, this proved not to be terribly difficult. The negotiations were aided by the fact that Weis and Hickman remained enthusiastic gamers themselves; they made sure that their agent and publisher got the deal done with very little hassle, and even agreed to provide an original novella to include in the box. Like Bates and Verdu, they were almost bizarrely trusting of Dahlgren. They didn’t even blink when he proposed packing the entire story arc of the Death Gate series — some 3000 pages in text form — into a single game. Although only five of the planned seven novels had yet appeared when the project began, Weis and Hickman freely shared their plans for the remainder of the series — most importantly, for the big finale where the worlds would be unified once again.

In what he called his “high concept” proposal for the game, Dahlgren laid out the plot in the broadest possible strokes:

This game is about a warrior whose race was imprisoned thousands of years ago in a place called the Labyrinth. His people were defeated by another race who broke up the world into four realms connected only by the Death Gate. In the game, the hero seeks to re-form the world by finding and assembling the scattered pieces of the World Seal.

None of it should work; it should feel like the Cliff’s Notes abridgement of the novels that it is. And yet Dalhgren made it work against all odds, largely by emphasizing the worlds of the books over the details of their plots. His most dazzling stroke was the insertion of the aforementioned World Seal as his McGuffin — one piece of it on each of the four worlds, in classic adventure-game fashion. With this scavenger hunt to serve as a straightforward motivation, you can get a taste of each world and interact with some of its characters without getting too bogged down in the more elaborate plot machinations of the books. Then fast-forward to the reunification, and you’re done.

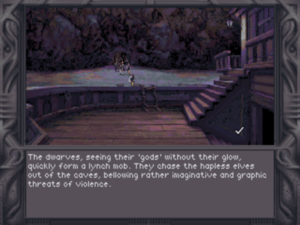

This isn’t to say that well-nigh encyclopedic amounts of material from the books aren’t missing from the game. These leavings encompass not just countless details of the environments and cultures that Weis and Hickman created, but also nuances of theme and character. The central protagonist of both the novels and the game is a Patryn named Haplo, but he cuts a very different figure in the two mediums. In the books, he’s a morally ambiguous character at best, a cold fish full of prejudice and at times outright malevolence; in the game, he’s a naïve innocent whose mistakes all arise from the deceptions perpetrated upon him by his master Xar, a fellow the player can see is up to no good about five minutes after meeting him for the first time. It’s telling that Dahlgren refers to Haplo as his game’s “hero” in the extract above; few readers of the books would choose that word. To wit: in the first of the novels, Haplo deliberately engineers a war on the world known as Arianus; in the game, he prevents one instead with a dose of good old-fashioned peace, love, and understanding. Johnny L. Wilson, the editor-in-chief of Computer Gaming World magazine as well as precisely the fan of the books that I am not, wrote in his otherwise positive preview of the game that “I just wish Haplo had a little more anger in him.”

Sometimes Death Gate can feel a bit like a vintage Star Trek episode, with Haplo in Captain Kirk’s role of the man who swoops in to solve centuries of conflict between two commercial breaks.

Nevertheless, even Wilson admitted that Death Gate passed the acid test of any adaptation: if you didn’t know that the game was based on a series of books before playing it, you wouldn’t feel like you were missing anything. It truly works as a self-contained experience, while still capturing the feel of its source material. It manages to present the complex cosmology of the novels in an intuitive, natural way, without ever burying you under info-dumps.

Death Gate has much else going for it as well. By the time of its release in late 1994, Legend had quietly turned into the most consistent adventure studio in the industry, with a design aesthetic defined by an absolute commitment to fairness which even LucasArts couldn’t match. If at times this commitment could lead Legend to play it a bit too safe — Legend’s puzzles seldom evince the inspired lunacy of LucasArts at their best — it’s vastly preferable to the other extreme, as exemplified by the sloppy designs of Sierra, their other major competitor. Glen Dahlgren recently wrote on the subject, using terms that seem suspiciously similar to the design philosophy which Bob Bates has repeatedly explicated in his own writings and lectures:

Every puzzle should provide an “Aha!” moment, where either you feel smart for having figured it out, or you discover the answer elsewhere and smack your head for NOT figuring it out. If you don’t have enough information in the game to figure out the solution logically, you never get that moment. In an adventure game, that moment is the fun!

The design isn’t intended to torment you or to “beat” you (the designer isn’t even there to enjoy besting the player, so it isn’t a satisfying goal to begin with). My philosophy has always been that a player puts his trust in the designer to take care of him. Once the player has lost that trust, he’ll give up.

So, while there are no puzzles in Death Gate that you’ll remember for years — or even days — afterward, there are likewise none that unduly block your progress through the story. Thanks to its conversations that can go on for minutes at a time, it plays almost as much like an interactive storybook as a puzzle-solving adventure game.

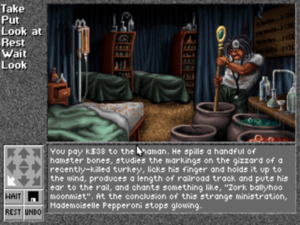

Which isn’t to say that it doesn’t have its share of more conventionally gamey pleasures as well. A highlight is its rune-based magic system, which smacks of the classic CRPGs Dungeon Master and Ultima Underworld more than that of any other adventure game with which I’m familiar. Combining the runes into magical recipes, then trying said recipes out on anything and everything, is a consistent source of fun. A surprising number of the silly things you can try are implemented, usually to very amusing effect. You can’t lock yourself out of victory without knowing it when doing stuff like this, and, while you can die, resurrection is always just a click of the “undo” button away. Thus you can experiment to your heart’s content.

The interface is the one which Legend introduced in Companions of Xanth: fully point and click now rather than parser-based, but still retaining a pronounced literary feel that betrays Bates and Verdu’s original conception of Legend as the heirs to Infocom’s legacy. Although the characters you meet are voice-acted, descriptions and narrations are still presented only in text.

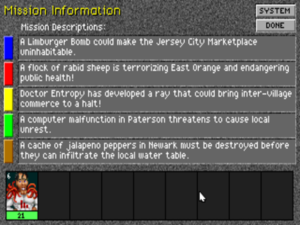

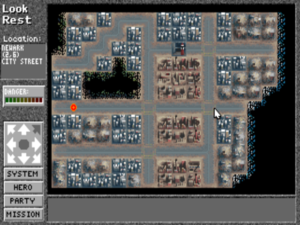

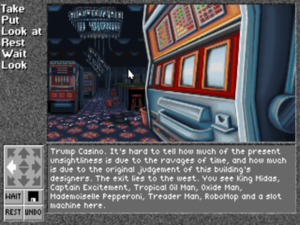

It’s easy to see which screens (like this one) are rendered in SVGA and which screens (like the previous one) are not.

Death Gate was, however, the first Legend game to make partial use of SVGA graphics, at a resolution of 640 X 480 rather than the 320 X 200 of VGA. The difference is marked. In fact, I’d go so far as to call the transition to SVGA the most significant transformation in computer-game audiovisuals since the Commodore Amiga appeared on the scene in 1985. SVGA games of the 1990s — the non-3D ones, at least — no longer have to be graded on a curve when it comes to their visual aesthetics. Much of the art in Death Gate would fit perfectly well into the latest indie sensation on Steam.

In another first for Legend, the opening movie and some of the later cut scenes are pre-rendered 3D, built using 3D Studio, a tool which was making a steady march across the games industry at the time.

All of these good qualities serve to make the rather negative review of Death Gate which Computer Gaming World published after Johnny Wilson’s positive preview seem all the more jarring. Peter Olafson dinged the game for its supposed inconsistencies of tone, for thoughtlessly mixing the serious with the comedic. This really is a problem with many adventure games then and now, which tend to collapse into comedy as a crutch for their ridiculously convoluted puzzles. And yet I don’t see Death Gate as one of those games at all. On the contrary: it strikes me as doing an admirable job of sticking to its guns and avoiding this tendency. The humor here is actually of a piece with the humor of the source material, as even Olafson admits in a tossed-off sentence that desperately needs further elaboration: “Even though this comic relief is present in the books, it seemed distracting and inappropriate in the game.” (Why exactly is that, Mr. Olafson?) Whether or not one finds the befuddled old wizard Zifnab, who wandered into the Death Gate universe from a dimensional warp in the Dragonlance world of Krynn, as hilarious as he’s obviously meant to be, his portrayal in the game isn’t notably different from his portrayal in the novels.

But another of Olafson’s criticisms is more telling, so much so that I’d like to quote it in full here:

I occasionally was haunted by a feeling that Death Gate’s technology has outstripped its genre. All the amenities lavished on the game — the enormous reservoir of digitized speech, the SVGA graphics, the animated cut scenes — build expectations for a game mechanism to complement them. And as agreeable as the engine may be, the game proper is essentially the same old object-oriented adventuring: take everything that’s not nailed down and use it in a conspiracy to take everything that is. There is something inherently trivial about inhabiting a lavish world and being stranded simply by want of a certain item. [It] is rather like having an orchestra play “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.”

If there is an overarching criticism to be raised against Death Gate, it’s this lack of will to innovate beyond the traditional confines of its genre. Indeed, the same criticism can be leveled against Legend’s catalog as a whole. While their adventures were the most consistently fair and literate in the industry during the 1990s, they were far from groundbreaking in formal terms. But then again, this eschewing of dizzying leaps in favor of keeping their feet planted firmly on solid ground does much to explain just why their games remain so playable to this day. In an industry that often fetishizes vision at the expense of craft, Legend’s games show how satisfying the tried and true can be when executed with thoroughgoing care.

Death Gate is a typical Legend game in another respect: it sold in reasonable but not overwhelming numbers; its sales figures remained in the five digits rather than the six or even seven to which the flashiest releases could aspire by 1994. Despite that, it wound up playing a role in Legend’s long-term evolution which was belied by its middling commercial performance.

Like many other small publishers, Legend found themselves increasingly threatened by the winds of change which blew through their industry as the 1990s wore on. The arrival of CD-ROM increased budgets enormously, thanks to the voice acting and richer and more elaborate graphic presentations that became not just possible but expected in this new era of 650 MB of storage. Meanwhile there arose a CD-ROM-fueled bubble in the marketplace, an ironic parallel to the bookware flash in the pan of exactly a decade earlier: titans of old media, from Disney to Random House, once again turned their attention to computer games as the potential Next Big Thing in publishing. How could little Legend hope to compete with the likes of them?

Well, as a wise person once said, if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em. By this point, Legend had established a solid relationship with Random House, first through their adaptations of Frederick Pohl’s Gateway novels and now with their work on Death Gate. With Random House eager to jump into computer games in a more concerted way, it made sense to both parties to cement the relationship — to, as they put it in their corporate-speak press release, “intensify the synergy established between them.” Mike Verdu spoke to me about it recently using more recognizably human language:

What drew Random House’s attention was the identity we had developed as a company that could take literary licenses and create properties out of them with the respect their authors thought they deserved. We had credibility as people who could take other authors’ worlds and build essentially new fictions in them, and take care of them and be a trusted partner in doing that. That had become sort of our trademark. As Random House was surveying what was then called “the new-media landscape,” they saw this as a very natural extension of their strength; it seemed like a very happy partnership.

Random House injected $2.5 million into Legend in the summer of 1994, a few months before Death Gate hit store shelves. The first fruits of the investment would appear the next year, when Legend released a three-CD full-motion-video extravaganza starring Michael Dorn, the actor best known as Worf from Star Trek: The Next Generation. That game cost far more to make than the ones Legend had been making before it, but its budget didn’t stem from arrogance or decadence. Legend was just trying to survive. And, accordingly to the conventional wisdom anyway, this was the only way to do it in the midst of the CD-ROM bubble.

In the end, the Random House deal would prove a mixed blessing at best. It gave the larger company a great deal of control over the smaller one — more control in reality than the latter had realized it would. It was structured to indemnify Random House against loss, such that Legend was on the hook to pay much of the investment back if they didn’t meet certain financial targets. For this reason not least, Random House would play an outsize role in the future in deciding which games Legend got to make. Not coincidentally, licensed games would come to dominate Legend’s output more than ever. In fact, during the entirety of their existence after the Random House deal Legend would release just one more game that wasn’t based on someone else’s preexisting intellectual property.

It was good, then, that they had a special talent for building upon the creativity of others. For they’d be doing a lot more of that sort of thing, sometimes for reasons that perhaps weren’t quite as pure as the honest love for the books in question that had spawned Gateway, Companions of Xanth, and Death Gate. Such was life if you wanted to run with the big boys.

(Sources: the book Designers and Dragons, ’70 to ’79 by Shannon Appelcline; Computer Gaming World of June 1993, November 1994, and February 1995; Questbusters 115; Retro Gamer 180. Online sources include Glen Dahlgren’s memoir of the making of Death Gate and Tracy Hickman’s interview at Mormon Artist. And my huge thanks to Bob Bates and Mike Verdu for their insights about Death Gate and all other things Legend during personal interviews.

Death Gate was briefly available for digital purchase at GOG.com, but has since disappeared again, presumably due to the difficulties associated with clearing the rights for licensed titles. It’s too large for me to host here even if I wasn’t nervous about the legal implications of doing so, but I have prepared a stub of the game that’s ready to go if you just add to the appropriate version of DOSBox for your platform of choice and an ISO image of the CD-ROM. A final hint: as of this writing, you can find the latter on archive.org if you look hard enough.)