Given the shadow which the original Master of Orion still casts over the gaming landscape of today, one might be forgiven for assuming, as many younger gamers doubtless do, that it was the very first conquer-the-galaxy grand-strategy game ever made. The reality, however, is quite different. For all that its position of influence is hardly misbegotten for other very good reasons, it was already the heir to a long tradition of such games at the time of its release in 1993. In fact, the tradition dates back to well before computer games as we know them today even existed.

The roots of the strategic space opera can be traced back to the tabletop game known as Diplomacy, designed by Allan B. Calhamer and first published in 1959 by Avalon Hill. Taking place in the years just prior to World War I, it put seven players in the roles of leaders of the various “great powers” of Europe. Although it included a playing board, tokens, and most of the other accoutrements of a typical board game, the real action, at least if you were playing it properly, was entirely social, in the alliances that were forged and broken and the shady deals that were struck. In this respect, it presaged many of the ideas that would later go into Dungeons & Dragons and other role-playing games. It thus represents an instant in gaming history as seminal in its own way as the 1954 publication of Avalon Hill’s Tactics, the canonical first tabletop wargame and the one which touched off the hobby of experiential gaming in general. But just as importantly for our purposes, Diplomacy‘s shifting alliances and the back-stabbings they led to would become an essential part of countless strategic space operas, including Master of Orion 34 years later.

Because getting seven friends together in the same room for the all-day affair that was a complete game of Diplomacy was almost as hard in the 1960s as it is today, inventive gamers developed systems for playing it via post; the first example of this breed would seem to date from 1963. And once players had started modifying the rules of Diplomacy to make it work under this new paradigm, it was a relatively short leap to begin making entirely new play-by-post games with new themes which shared some commonalities of approach with Calhamer’s magnum opus.

Thus in December of 1966, Dan Brannon announced a play-by-post game called Xeno, whose concept sounds very familiar indeed in the broad strokes. Each player started with a cluster of five planets — a tiny toehold in a sprawling, unknown galaxy waiting to be colonized. “The vastness of the playing space, the secrecy of the identity of the other players, the secrecy of the locations of ships and planets, the total lack of information without efforts of investigation, all these factors are meant to create the real problems of a race trying to expand to other planets,” wrote Brannon. Although the new game would be like Diplomacy in that it would presumably still culminate in negotiations, betrayals, and the inevitable final war to determine the ultimate victor, these stages would now be preceded by those of exploration and colonization, until a galaxy that had seemed so unfathomably big at the start proved not to be big enough to accommodate all of its would-be space empires. Certainly all of this too will be familiar to any player of Master of Orion or one of its heirs. Brannon’s game even included a tech tree of sorts, with players able to acquire better engines, weapons, and shields for their ships every eight turns they managed to survive.

In practice, Xeno played out at a pace to which the word “glacial” hardly does justice. The game didn’t really get started until September of 1967, and by a year after that just three turns had been completed. I don’t know whether a single full game of it was ever finished. Nevertheless, it proved hugely influential within the small community of experiential-gaming fanzines and play-by-post enthusiasts. The first similar game, called Galaxy and run by H. David Montgomery, had already appeared before Xeno had processed its third turn.

But the idea was, literally and figuratively speaking, too big for the medium for which it had been devised; it was just too compelling to remain confined to those few stalwart souls with the patience for play-by-post gaming. It soon branched out into two new mediums, each of which offered a more immediate sort of satisfaction.

In 1975, following rejections from Avalon Hill and others, one Howard Thompson formed his own company to publish the face-to-face board game Stellar Conquest, the first strategic space opera to appear in an actual box on store shelves. When Stellar Conquest became a success, it spawned a string of similar board games with titles like Godsfire, Outreach, Second Empire, and Starfall during this, the heyday of experiential gaming on the tabletop. But the big problem with such games was their sheer scope and math-heavy nature, which were enough to test the limits of many a salty old grognard who usually reveled in complexity. They all took at least three or four hours to play in their simplest variants, and a single game of at least one of them — SPI’s Outreach — could absorb weeks of gaming Saturdays. Meanwhile they were all dependent on pages and pages of fiddly manual calculations, in the time before spreadsheet macros or even handheld calculators were commonplace. (One hates to contemplate the plight of the Outreach group who have just spent the last two months resolving who shall become master of the galaxy, only to discover that the victor made a mistake on her production worksheet back on the second turn which invalidated all of the numbers that followed…) These games were, in other words, crying out for computerization.

Luckily, then, that too had already started to happen by the end of the 1970s. One of the reasons that play-by-post games of this type tended to run so sluggishly — beyond, that is, the inherent sluggishness of the medium itself — came down to the same problem as that faced by their tabletop progeny: the burden their size and complexity placed on their administrators. Therefore in 1976, Rick Loomis, the founder of a little company called Flying Buffalo, started running the commercial play-by-post game Starweb on what gaming historian Shannon Appelcline has called “probably the first computer ever purchased exclusively to play games” (or, at least, to administrate them): a $14,000 Raytheon 704 minicomputer. He would continue to run Starweb for more than thirty years — albeit presumably not on the same computer throughout that time.

But the first full-fledged incarnation of the computerized strategic space opera — in the sense of a self-contained game meant to be played locally on a single computer — arrived only in 1983. Called Reach for the Stars, it was the first fruit of what would turn into a long-running and prolific partnership between the Aussies Roger Keating and Ian Trout, who in that rather grandiose fashion that was so typical of grognard culture had named themselves the Strategic Studies Group. Reach for the Stars was based so heavily upon Stellar Conquest that it’s been called an outright unlicensed clone. Nevertheless, it’s a remarkable achievement for the way that it manages to capture that sense of size and scope that is such a huge part of these games’ appeal on 8-bit Apple IIs and Commodore 64s with just 64 K of memory. Although the whole is necessarily rather bare-bones compared to what would come later, the computer players’ artificial intelligence, always a point of pride with Keating and Trout, is surprisingly effective; on the harder difficulty level, the computer can truly give you a run for your money, and seems to do so without relying solely on egregious cheating.

It doesn’t look like much, but the basic hallmarks of the strategic space opera are all there in Reach for the Stars.

Reach for the Stars did very well, prompting updated ports to more powerful machines like the Apple Macintosh and IIGS and the Commodore Amiga as the decade wore on. A modest trickle of other boxed computer games of a similar stripe also appeared, albeit none which did much to comprehensively improve on SSG’s effort: Imperium Galactum, Spaceward Ho!, Armada 2525, Pax Imperia. Meanwhile the commercial online service CompuServe offered up MegaWars III, in which up to 100 players vied for control of the galaxy; it played a bit like one of those years-long play-by-post campaigns of yore compressed into four to six weeks of constant — and expensive, given CompuServe’s hourly dial-up rates — action and intrigue. Even the shareware scene got in on the act, via titles like Anacreon: Reconstruction 4021 and the earliest versions of the cult classic VGA Planets, a game which is still actively maintained and played to this day. And then, finally, along came Master of Orion in 1993 to truly take this style of game to the next level.

Had things gone just a little bit differently, Master of Orion too might have been a shareware release. It was designed in the spare time of Steve Barcia, an electrical engineer living in Austin, Texas, and programmed by Steve himself, his wife Marcia Barcia, and their friend Ken Burd. Steve claims not ever to have played any of the computer games I’ve just mentioned, but, as an avid and longtime tabletop gamer, he was very familiar with Stellar Conquest and a number of its successors. (No surprise there: Howard Thompson and his game were in fact also products of Austin’s vibrant board-gaming scene.)

After working on their computer game, which they called Star Lords, on and off for years, the little band of hobbyist programmers submitted it to MicroProse, whose grand-strategy game of Civilization, a creation of their leading in-house designer Sid Meier, had just taken the world by storm. A MicroProse producer named Jeff Johannigman — himself another member of the Austin gaming fraternity, as it happened, one who had just left Origin Systems in Austin to join MicroProse up in Baltimore — took a shine to the unpolished gem and signed its creators to develop it further. Seeing their hobby about to become a real business, the trio quit their jobs, took the name of SimTex, and leased a cramped office above a gyro joint to finish their game under Johannigman’s remote supervision, with a little additional help from MicroProse’s art department.

A fellow named Alan Emrich was one of most prominent voices in strategy-game criticism at the time; he was the foremost scribe on the subject at Computer Gaming World magazine, the industry’s accepted journal of record, and had just published a book-length strategy guide on Civilization in tandem with Johnny Wilson, the same magazine’s senior editor. Thanks to that project, Emrich was well-connected with MicroProse, and was happy to serve as a sounding board for them. And so, one fateful day very early in 1993, Johannigman asked if he’d like to have a look at a new submission called Star Lords.

As Emrich himself puts it, his initial impressions “were not that great.” He remembers thinking the game looked like “something from the late 1980s” — an eternity in the fast-changing computing scene of the early 1990s. Yet there was just something about it; the more he played, the more he wanted to keep playing. So, he shared Star Lords with his friend Tom Hughes, with whom he’d been playing tabletop and computerized strategy games for twenty years. Hughes had the same experience. Emrich:

After intense, repeated playing of the game, Tom and I were soon making numerous suggestions to [Johannigman], who, in turn, got tired of passing them on to the designer and lead programmer, Steve Barcia. Soon, we were talking to Steve directly. The telephone lines were burning regularly and a lot of ideas went back and forth. All the while, Steve was cooking up a better and better game. It was during this time that the title changed to Master of Orion and the game’s theme and focus crystallized.

I wrote a sneak preview for Computer Gaming World magazine where I indicated that Master of Orion was shaping up to be a good game. It had a lot of promise, but I didn’t think it was up there with Sid Meier’s Civilization, the hobby’s hallmark of strategy gaming at that time. But by the time that story hit the newsstands, I had changed my mind. I found myself still playing the game constantly and was reflecting on that fact when Tom called me. We talked about Master of Orion, of course, and Tom said, “You know, I think this game might become more addicting even than Civilization.” I replied, “You know, I think it already is.”

I was hard on Emrich in earlier articles for his silly assertion that Civilization‘s inclusion of global warming as a threat to progress and women’s suffrage as a Wonder of the World constituted some form of surrender to left-wing political correctness, as I was for his even sillier assertion that the game’s simplistic and highly artificial economic model could somehow be held up as proof for the pseudo-scientific theory of trickle-down economics. Therefore let me be very clear in praising him here: Emrich and Hughes played an absolutely massive role in making Master of Orion one of the greatest strategy games of all time. Their contribution was such that SimTex took the unusual step of adding to the credits listing a “Special Thanks to Alan Emrich and Tom Hughes for their invaluable design critiquing and suggestions.” If anything, that credit would seem to be more ungenerous than the opposite. By all indications, a pair of full-fledged co-designer credits wouldn’t have been out of proportion to the reality of their contribution. The two would go on to write the exhaustive official strategy guide for the game, a tome numbering more than 400 pages. No one could have been more qualified to tackle that project.

As if all that wasn’t enough, Emrich did one more great service for Master of Orion and, one might even say, for gaming in general. In a “revealing sneak preview” of the game, published in the September 1993 issue of Computer Gaming World, he pronounced it to be “rated XXXX.” After the requisite measure of back-patting for such edgy turns of phrase as these, Emrich settled down to explain what he really meant by the label: “XXXX” in this context stood for “EXplore, EXpand, EXploit, and EXterminate.” And thus was a new sub-genre label born. The formulation from the article was quickly shortened to “4X” by enterprising gamers uninterested in making strained allusions to pornographic films. In that form, it would be applied to countless titles going forward, right up to the present day, and retroactively applied to countless titles of the past, including all of the earlier space operas I’ve just described as well as the original Civilization — a game to which the “EXterminate” part of the label fits perhaps less well, but such is life.

Emrich’s article also creates an amusing distinction for the more pedantic ludic taxonomists and linguists among us. Although Master of Orion definitely was not, as we’ve now seen at some length, the first 4X game in the abstract, it was the very first 4X game to be called a 4X game. Maybe this accounts for some of the pride of place it holds in modern gaming culture?

However that may be, though, the lion’s share of the credit for Master of Orion‘s enduring influence must surely be ascribed to what a superb game it is in its own right. If it didn’t invent the 4X space opera, it did in some sense perfect it, at least in its digital form. It doesn’t do anything conceptually new on the face of it — you’re still leading an alien race as it expands through a randomly created galaxy, competing with other races in the fields of economics, technology, diplomacy, and warfare to become the dominant civilization — but it just does it all so well.

A new game of Master of Orion begins with you choosing a galaxy size (from small to huge), a difficulty level (from simple to impossible), and a quantity of opposing aliens to compete against (from one to five). Then you choose which specific race you would like to play; you have ten possibilities in all, drawing from a well-worn book of science-fiction tropes, from angry cats in space to hive-mind-powered insects, from living rocks to pacifistic brainiacs, alongside the inevitable humans. Once you’ve made your choice, you’re cast into the deep end — or rather into deep space — with a single half-developed planet, a colony ship for settling a second planet as soon as you find a likely candidate, two unarmed scout ships for exploring for just such a candidate, and a minimal set of starting technologies.

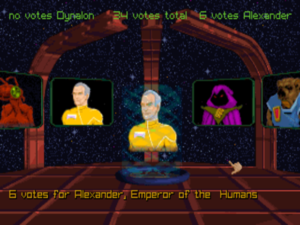

You must parlay these underwhelming tools into galactic domination hundreds of turns later. You can take the last part of the 4X tag literally and win out by utterly exterminating all of your rivals, but a slightly less genocidal approach is a victory in the “Galactic Council” which meets every quarter-century (i.e., every 25 turns). Here everyone can vote on which of the two most currently populous empires’ leaders they prefer to appoint as ruler of the galaxy, with “everyone” in this context including the two leading emperors themselves. Each empire gets a number of votes determined by its population, and the first to collect two-thirds of the total vote wins outright. (Well, almost… it is possible for you to refuse to respect the outcome of a vote that goes against you, but doing so will cause all of your rivals to declare immediate and perpetual war against you, whilst effectively pooling all of their own resources and technology. Good luck with that!)

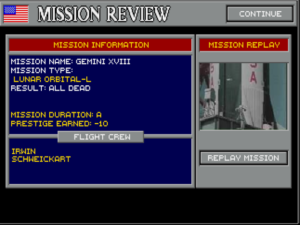

A typical game of Master of Orion plays out over three broad stages. The first stage is the land grab, the wide-open exploration and colonization phase that happens before you meet your rival aliens. Here your challenge is to balance the economic development of your existing planets against your need to settle as many new ones as possible to put yourself in a good position for the mid-game. (When exactly do I stop spending my home planet’s resources on improving its own infrastructure and start using them to build more colony ships?) The mid-game begins when you start to bump into your rivals, and comes to entail much jockeying for influence, as the various races begin to sort themselves into rival factions. (The Alkaris, bird-like creatures, loathe the Mrrshans, the aforementioned race of frenzied pussycats, and their loathing is returned in kind. I don’t have strong feelings about either one — but whose side would it most behoove me to choose from a purely strategic perspective?) The endgame is nigh when there is no more room for anyone to expand, apart from taking planets from a rival by force, and the once-expansive galaxy suddenly seems claustrophobic. It often, although by no means always, is marked by a massive war that finally secures somebody that elusive two-thirds majority in the Galactic Council. (I’m so close now! Do I attack those stubbornly intractable Bulrathi to try to knock down their population and get myself over the two-thirds threshold that way, or do I keep trying to sweet-talk and bribe them into voting for me?) The length and character of all of these stages will of course greatly depend on the initial setup you chose; the first stage might be all but nonexistent in a small galaxy with five rivals, while it will go on for a long, long time indeed in a huge galaxy with just one or two opponents. (The former scenario is, for the record, far more challenging.)

And that’s how it goes, generally speaking. Yet the core genius of Master of Orion actually lies in how resistant it is to generalization. It’s no exaggeration to say that there really is no “typical” game; I’ve enjoyed plenty which played out in nothing like the pattern I’ve just described for you. I’ve played games in which I never fired a single shot in anger, even ones where I’ve never built a single armed ship of war, just as I’ve played others where I was in a constant war for survival from beginning to end. Master of Orion is gaming’s best box of chocolates; you never know what you’re going to get when you jump into a new galaxy. Everything about the design is engineered to keep you from falling back on patterns universally applicable to the “typical” game. It’s this quality, more so than any other, that makes Master of Orion so consistently rewarding. If I was to be stranded on the proverbial desert island, I have a pretty good idea of at least one of the games I’d choose to take with me.

I’ll return momentarily to the question of just how Master of Orion manages to build so much variation into a fairly simple set of core rules. I think it might be instructive to do so, however, in comparison with another game, one I’ve already had occasion to mention several times in this article: Civilization.

As I’m so often at pains to point out, game design is, like any creative pursuit, a form of public dialog. Certainly Civilization itself comes with a long list of antecedents, including most notably Walter Bright’s mainframe game Empire, Dani Bunten Berry’s PC game Seven Cities of Gold, and the Avalon Hill board game with which Civilization shares its name. Likewise, Civilization has its progeny, among them Master of Orion. By no means was it the sole influence on the latter; as we’ve seen, Master of Orion was also greatly influenced by the 4X space-opera tradition in board games, especially during its early phases of development.

Still, the mark of Civilization as well can be seen all over its finished design. (After all, Alan Emrich had just literally written the book on Civilization when he started bombarding Barcia with design suggestions…) For example, Master of Orion, unlike all of its space-opera predecessors, on the computer or otherwise, doesn’t bother at all with multiplayer options, preferring to optimize the single-player experience in their stead. One can’t help but feel that it was Civilization, which was likewise bereft of the multiplayer options that earlier grand-strategy games had always included as a matter of course, that empowered Steve Barcia and company to go this way.

At the same time, though, we cannot say that Jeff Johannigman was being particularly accurate when he took to calling Master of Orion “Civilization in space” for the benefit of journalists. For all that it’s easy enough to understand what made such shorthand so tempting — this new project too was a grand-strategy game played on a huge scale, incorporating technology, economics, diplomacy, and military conflict — it wasn’t ultimately fair to either game. Master of Orion is very much its own thing. Its interface, for example, is completely different. (Ironically, Barcia’s follow-up to Master of Orion, the fantasy 4X Master of Magic, hews much closer to Civilization in that respect.) In Master of Orion, Civilization‘s influence often runs as much in a negative as a positive direction; that is to say, there are places where the later design is lifting ideas from the earlier one, but also taking it upon itself to correct perceived weaknesses in their implementation.

I have to use the qualifier “perceived” there because the two games have such different personalities. Simply put, Civilization prioritizes its fictional context over its actual mechanics, while Master of Orion does just the opposite. Together they illustrate the flexibility of the interactive digital medium, showing how great games can be great in such markedly different ways, even when they’re as closely linked in terms of genre as these two are.

Civilization explicitly bills itself as a grand journey through human history, from the time in our distant past when the first hunter-gatherers settled down in villages to an optimistic near-future in space. The rules underpinning the journey are loose-goosey, full of potential exploits. The most infamous of these is undoubtedly the barbarian-horde strategy, in which you research only a few minimal technologies necessary for war-making and never attempt to evolve your society or participate in any meaningful diplomacy thereafter, but merely flood the world with miserable hardscrabble cities supporting primitive armies, attacking everything that moves until every other civilization is extinct. At the lower and moderate difficulty levels at least, this strategy works every single time, albeit whilst bypassing most of what the game was meant to be about. As put by Ralph Betza, a contributor to an early Civilization strategy guide posted to Usenet: “You can always play Despotic Conquest, regardless of the world you find yourself starting with, and you can always win without using any of the many ways to cheat. When you choose any other strategy, you are deliberately risking a loss in order to make the game more interesting.”

So very much in Civilization is of limited utility at best in purely mechanical terms. Many or most of the much-vaunted Wonders of the World, for example, really aren’t worth the cost you have to pay for them. But that’s okay; you pay for them anyway because you like the idea of having built the Pyramids of Giza or the Globe Theatre or Project Apollo, just as you choose not to go all Genghis Khan on the world because you’d rather build a civilization you can feel proud of. Perhaps the clearest statement of Civilization‘s guiding design philosophy can be found in the manual. It says that, even if you make it all the way to the end of the game only to see one of your rivals achieve the ultimate goal of mounting an expedition to Alpha Centauri before you do, “the successful direction of your civilization through the centuries is an achievement. You have survived countless wars, the pollution of the industrial age, and the risks of nuclear weapons.” Or, as Sid Meier himself puts it, “a game of Civilization is an epic story.”

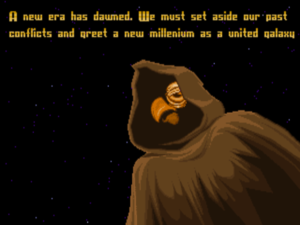

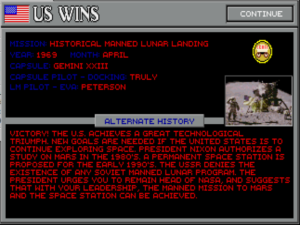

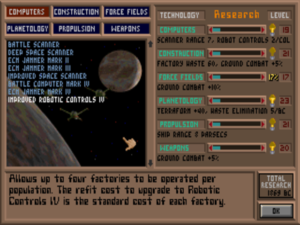

Such sentiments are deeply foreign to Master of Orion; this is a zero-sum game if ever there was one. If you lose the final Galactic Council vote, there’s no attaboy for getting this far, much less any consolation delivered that the galaxy has entered a new era of peaceful cooperation with some other race in the leadership role. Instead the closing cinematic tells you that you’ve left the known galaxy and “set forth to conquer new worlds, vowing to return and claim the renowned title of Master of Orion.” (Better to rule in Hell, right?) There are no Wonders of the World in Master of Orion, and, while there is a tech tree to work through, you won’t find on it any of Civilization‘s more humanistic advances, such as Chivalry or Mysticism, or even Communism or The Corporation. What you get instead are technologies — it’s telling that Master of Orion talks about a “tech tree,” while Civilization prefers the word “advances” — with a direct practical application to settling worlds and making war, divided into the STEM-centric categories of Computers, Construction, Force Fields, Planetology, Propulsion, and Weapons.

So, Civilization is the more idealistic, more educational, perhaps even the nobler of the two games. And yet it often plays a little awkwardly — which awkwardness we forgive because of its aspirational qualities. Master of Orion‘s fictional context is a much thinner veneer to stretch over its mechanics, while words like “idealistic” simply don’t exist in its vocabulary. And yet, being without any high-flown themes to fall back on, it makes sure that its mechanics are absolutely tight. These dichotomies can create a dilemma for a critic like yours truly. If you asked me which game presents a better argument for gaming writ large as a potentially uplifting, ennobling pursuit, I know which of the two I’d have to point to. But then, when I’m just looking for a fun, challenging, intriguing game to play… well, let’s just say that I’ve played a lot more Master of Orion than Civilization over the last quarter-century. Indeed, Master of Orion can easily be read as the work of a designer who looked at Civilization and was unimpressed with its touchy-feely side, then set out to make a game that fixed all the other failings which that side obscured.

By way of a first example, let’s consider the two games’ implementation of an advances chart — or a tech tree, whichever you prefer. Arguably the most transformative single advance in Civilization is Railroads; they let you move your military units between your cities almost instantaneously, which makes attacks much easier and quicker to mount for warlike players and enables the more peaceful types to protect their holdings with a much smaller (and thus less expensive) standing army. The Railroads advance is so pivotal that some players build their entire strategy around acquiring it as soon as possible, by finding it on the advances chart as soon as the game begins in 4000 BC and working their way backward to find the absolute shortest path for reaching it. This is obviously problematic from a storytelling standpoint; it’s not as if the earliest villagers set about learning the craft of Pottery with an eye toward getting their hands on Railroads 6000 years later. More importantly, though, it’s damaging to the longevity of the game itself, in that it means that players can and will always employ that same Railroads strategy just as soon as they figure out what a winner it is. Here we stumble over one of the subtler but nonetheless significant axioms of game design: if you give players a hammer that works on every nail, many or most of them will use it — and only it — over and over again, even if it winds up decreasing their overall enjoyment. It’s for this reason that some players continue to use even the barbarian-horde strategy in Civilization, boring though it is. Or, to take an outside example: how many designers of CRPGs have lovingly crafted dozens of spells with their own unique advantages and disadvantages, only to watch players burn up everything they encounter with a trusty Fireball?

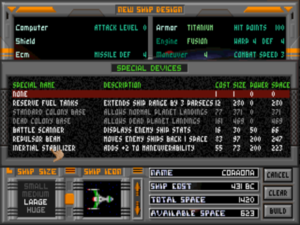

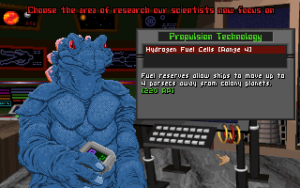

Master of Orion, on the other hand, works hard at every turn to make such one-size-fits-all strategies impossible — and nowhere more so than in its tech tree. When a new game begins, each race is given a randomized selection of technologies that are possible for it to research, constituting only about half of the total number of technologies in the game. Thus, while a technology roughly equivalent to Civilization‘s Railroads does exist in Master of Orion — Star Gates — you don’t know if this or any other technology is actually available to you until you advance far enough up the tree to reach the spot where it ought to be. You can’t base your entire strategy around a predictable technology progression. While you can acquire technologies that didn’t make it into your tree by trading with other empires, bullying them into giving them to you, or attacking their planets and taking them, that’s a much more fraught, uncertain path to go down than doing the research yourself, one that requires a fair amount of seat-of-your-pants strategy in its own right. Any way you slice it, in other words, you have to improvise.

We’ve been lucky here in that Hydrogen Fuel Cells, the first range-extending technology and a fairly cheap one, is available in our tree. If it wasn’t, and if we didn’t have a lot of stars conveniently close by, we’d have to dedicate our entire empire to attaining a more advanced and thus more expensive range-extending technology, lest we be left behind in the initial land grab. But this would of course mean neglecting other aspects of our empire’s development. Trade-offs like this are a constant fact of life in Master of Orion.

This one clever design choice has repercussions for every other aspect of the game. Take, for instance, the endlessly fascinating game-within-a-game of designing your fleet of starships. If the tech tree was static, players would inevitably settle upon a small set of go-to designs that worked for their style of play. As it is, though, every new ship is a fresh balancing act, its equipment calibrated to maximize your side’s technological strengths and mitigate its weaknesses, while also taking into careful account the strengths and weaknesses of the foe you expect to use it against, about which you’ve hopefully been compiling information through your espionage network. Do you build a huge number of tiny, fast, maneuverable fighters, or do you build just a few lumbering galactic dreadnoughts? Or do you build something in between? There are no universally correct answers, just sets of changing circumstances.

Another source of dynamism are the alien races you play and those you play against. The cultures in Civilization have no intrinsic strengths and weaknesses, just sets of leader tendencies when played by the computer; for your part, you’re free to play the Mongols as pacifists, or for that matter the Russians as paragons of liberal democracy and global cooperation. But in Master of Orion, each race’s unique affordances force you to play it differently. Likewise, each opposing race’s affordances in combination with those of your own force you to respond differently to that race when you encounter it, whether on the other side of a diplomats’ table or on a battlefield in space. Further, most races have one technology they’re unusually good at researching and one they’re unusually bad at. Throw in varying degrees of affinity and prejudice toward the other races, and, again, you’ve got an enormous amount of variation which defies cookie-cutter strategizing. (It’s worth noting that there’s a great deal of asymmetry here; Steve Barcia and his helpers didn’t share so many modern designers’ obsession with symmetrical play balance above all else. Some races are clearly more powerful than others: the brainiac Psilons get a huge research bonus, the insectoid Klackons get a huge bonus in worker productivity, and the Humans get huge bonuses in trade and diplomacy. Meanwhile the avian Alkaris, the feline Mrrshan, and the ursine Bulrathis have bonuses which only apply during combat, and can be overcome fairly easily by races with other, more all-encompassing advantages.)

There are yet more touches to bring yet more dynamism. Random events occur from time to time in the galaxy, some of which can change everything at a stroke: a gigantic space amoeba might show up and start eating stars, forcing everyone to forget their petty squabbles for a while and band together against this apocalyptic threat. And then there’s the mysterious star Orion, from which the game takes it name, which houses the wonders of a long-dead alien culture from the mythical past. Taking possession of it might just win the game for you — but first you’ll have to defeat its almost inconceivably powerful Guardian.

One of the perennial problems of 4X games, Civilization among them, is the long anticlimax, which begins at that point when you know you’re going to conquer the world or be the first to blast off for Alpha Centauri, but well before you actually do so. (What Civilization player isn’t familiar with the delights of scouring the map for that one remaining rival city tucked away on some forgotten island in some forgotten corner?) Here too Master of Orion comes with a mitigating idea, in the form of the Galactic Council whose workings I’ve already described. It means that, as soon as you can collect two-thirds of the vote — whether through wily diplomacy or the simpler expedient of conquering until two-thirds of the galaxy’s population is your own — the game ends and you get your victory screen.

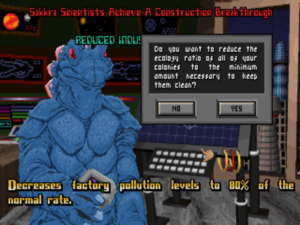

Indeed, one of the overarching design themes of Master of Orion is its determination to minimize the boring stuff. It must be admitted, of course, that boredom is in the eye of the beholder. Non-fans have occasionally dismissed the whole 4X space-opera sub-genre as “Microsoft Excel in space,” and Master of Orion too requires a level of comfort with — or, better yet, a degree of fascination with — numbers and ratios; you’ll spend at least as much time tinkering with your economy as you will engaging in space battles. Yet the game does everything it can to minimize the pain here as well. While hardly a simple game in absolute terms, it is quite a streamlined example of its type; certainly it’s much less fiddly than Civilization. Planet management is abstracted into a set of five sliding ratio bars, allowing you decide what percentage of that planet’s total output should be devoted to building ships, building defensive installations, building industrial infrastructure, cleaning up pollution, and researching new technologies. Unlike in Civilization, there is no list of specialized structures to build one at a time, much less a need to laboriously develop the land square by square with a specialized unit. Some degree of micro-management is always going to be in the nature of this type of game, but managing dozens of planets in Master of Orion is far less painful than managing dozens of cities in Civilization.

The research screen as well operates through sliding ratio bars which let you decide how much effort to devote to each of six categories of technology. In other words, you’re almost always researching multiple advances at once in Master of Orion, whereas in Civilization you only research one at a time. Further, you can never predict for sure when a technology will arrive; while each has a base cost in research points, “paying” it leads only to a slowly increasing randomized chance of acquiring the technology on any given turn. (That’s the meaning of the “17%” next to Force Fields in the screenshot above.) You also receive bonuses for maintaining steady research over a long run of turns, rather than throwing all of your research points into one technology, then into something else, etc. All of this as well serves to make the game more unpredictable and dynamic.

In short, Master of Orion tries really, really hard to work with you rather than against you, and succeeds to such a degree that it can sometimes feel like the game is reading your mind. A reductionist critic of the sort I can be on occasion might say that there are just two types of games: those that actually got played before their release and those that didn’t. With only rare exceptions, this distinction, more so than the intrinsic brilliance of the design team or any other factor, is the best predictor of the quality of the end result. Master of Orion is clearly a game that got played, and played extensively, with all of the feedback thus gathered being incorporated into the final design. The interface is about as perfect as the technical limitations of 1993 allow it to be; nothing you can possibly want to do is more than two clicks away. And the game is replete with subtle little conveniences that you only come to appreciate with time — like, just to take one example, the way it asks if you want to automatically adjust the ecology spending on every one of your planets when you acquire a more efficient environmental-cleanup technology. This lived-in quality can only be acquired the honest, old-fashioned way: by giving your game to actual players and then listening to what they tell you about it, whether the points they bring up are big or small, game-breaking or trivial.

This thoroughgoing commitment to quality is made all the more remarkable by our knowledge of circumstances inside MicroProse while Master of Orion was going through these critical final phases of its development. When the contract to publish the game was signed, MicroProse was in desperate financial straits, having lost bundles on an ill-advised standup-arcade game along with expensive forays into adventure games and CRPGs, genres far from their traditional bread and butter of military simulations and grand-strategy games. Although other projects suffered badly from the chaos, Master of Orion, perhaps because it was a rather low-priority project entrusted largely to an outside team located over a thousand miles away, was given the time and space to become its best self. It was still a work in progress on June 21, 1993, when MicroProse’s mercurial, ofttimes erratic founder and CEO “Wild Bill” Stealey sold the company to Spectrum Holobyte, a publisher with a relatively small portfolio of extant games but a big roll of venture capital behind them.

Master of Orion thus became one of the first releases from the newly conjoined entity on October 1, 1993. Helped along by the evangelism of Alan Emrich and his pals at Computer Gaming World, it did about as well as such a cerebral title, almost completely bereft of audiovisual bells and whistles, could possibly do in the new age of multimedia computing; it became the biggest strategy hit since Civilization, and the biggest 4X space opera to that point, in any medium. Later computerized iterations on the concept, including its own sequels, doubtless sold more copies in absolute numbers, but the original Master of Orion has gone on to become one of the truly seminal titles in gaming history, almost as much so as the original Civilization. It remains the game to which every new 4X space opera — and there have been many of them, far more than have tried to capture the more elusively idealistic appeal of Civilization — must be compared.

Sometimes a status such as that enjoyed by Master of Orion arrives thanks to an historical accident or a mere flashy technical innovation, but that is definitively not the case here. Master of Orion remains as rewarding as ever in all its near-infinite variation. Personally, I like to embrace its dynamic spirit for everything it’s worth by throwing a (virtual) die to set up a new game, letting the Universe decide what size galaxy I play in, how many rivals I play with, and which race I play myself. The end result never fails to be enjoyable, whether it winds up a desperate free-for-all between six alien civilizations compressed into a tiny galaxy with just 24 stars, or a wide-open, stately game of peaceful exploration in a galaxy with over 100 of them. In short, Master of Orion is the most inexhaustible well of entertainment I’ve ever found in the form of a single computer game — a timeless classic that never fails to punish you for playing lazy, but never fails to reward you for playing well. I’ve been pulling it out to try to conquer another random galaxy at least once every year or two for half my life already. I suspect I’ll still be doing so until the day I die.

(Sources: the books Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play by Morgan Ramsay, Designers & Dragons, Volume 1: The 1970s by Shannon Appelcline, and Master of Orion: The Official Strategy Guide by Alan Emrich and Tom E. Hughes, Jr.; Computer Gaming World of December 1983, June/July 1985, October 1991, June 1993, August 1993, September 1993, December 1993, and October 1995; Commodore Disk User of May 1988; Softline of March 1983. Online sources include “Per Aspera Ad Astra” by Jon Peterson from ROMchip, Alan Emrich’s historical notes from the old Master of Orion III site, a Steve Barcia video interview which originally appeared in the CD-ROM magazine Interactive Entertainment., and the Civilization Usenet FAQ, lasted updated by “Dave” in 1994.

Master of Orion I and II are available for purchase together from GOG.com. I highly recommend a tutorial, compiled many years ago by Sirian and now available only via archive.org, as an excellent way for new players to learn the ropes.)