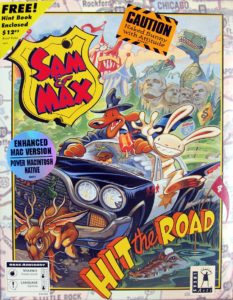

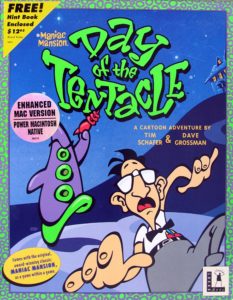

Day of the Tentacle wasn’t the only splendid adventure game which LucasArts released in 1993. Some five months after that classic, just in time for Christmas, they unveiled Sam & Max Hit the Road.

At first glance, the two games may seem disarmingly, even dismayingly similar; Sam and Max is yet another cartoon comedy in an oeuvre fairly bursting with the things. Look a little harder, though, and some pronounced differences in the two games’ personalities quickly start to emerge. Day of the Tentacle is clever and funny in a mildly subversive but family-friendly way, very much of a piece with the old Warner Bros. cartoons its aesthetic presentation so consciously emulates. Sam & Max, however, is something else entirely, more in tune with an early 1990s wave of boundary-pushing prime-time cartoons for an older audience — think The Simpsons and Beavis & Butt-Head — than the Saturday morning reels of yore. Certainly there are no life lessons to be derived herein; steeped in postmodern cynicism, this game has a moral foundation that is, as its principal creator once put, “built on quicksand.” Yet it has a saving grace: it’s really, really funny. If anything, it’s even funnier than Day of the Tentacle, which is quite a high bar to clear. This is a game with some real bite to it — and I’m not just talking about the prominent incisors on Max, the violently unhinged rabbit who so often steals the show.

Max’s partner Sam is a modestly more stable Irish wolfhound in a rumpled three-piece suit who walks and talks like a cross between Joe Friday and Maxwell Smart. Together, the two of them solve crimes in the tradition of hard-bitten detectives like Sam Spade. Or, as Sam the dog prefers to put it, they’re “freelance police,” working “to protect the rights of all those whose rights seem to require protecting at whatever particular time seems appropriate or convenient to all involved parties.” As for Max, he just likes to beat, blow, shoot, and generally eff stuff up.

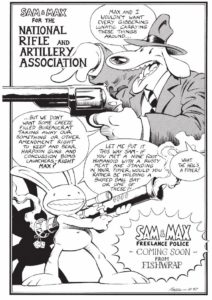

Sam and Max first made their names as the stars of an indie comic book, and carried a certain indie sensibility with them when they strolled onto our monitor screens. The safe suburban world of gaming had never seen anything quite like this duo — boldly but also smartly written, aggressively confrontational, and absolutely hilarious as they wandered a landscape built out of junk media and decrepit Americana.

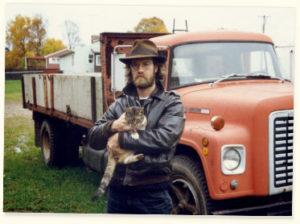

This not-so-cuddly duo of anthropomorphized animals was the brainchild of one Steve Purcell, a San Francisco artist who invented them with a little help from his brother while both were still children. When he enrolled at the California College of Arts and Crafts circa 1980, he started drawing them for the student newspaper there. They fell by the wayside, however, when Purcell graduated and started taking work as an independent illustrator wherever he could find it, drawing everything from computer-game boxes to Marvel comics.

While Purcell was making ends meet thusly, a friend of his named Steve Moncuse was enjoying considerable buzz within the San Francisco hipster scene for his self-published series of Fish Police comics, which bore some obvious conceptual similarities to Sam and Max. Eager to add some mammals to his stable of marine investigators, Moncuse convinced Purcell to make a full-fledged Sam & Max comic book for his own Fishwrap Productions. “I had never written, penciled, and inked my own comic book before that,” remembers Purcell — but he was up for the challenge. In 1987, the first issue of Sam & Max: Freelance Police was published, containing two stories in its 32 pages. Over the next six years or so, more showcases for the animal detectives appeared intermittently under a variety of formats and imprints, whenever Purcell could spare enough time from his paying gigs — there was very little money at all in independent comics — to draw them. By 1993, their scattered canon was enough to fill perhaps half a dozen traditional comic books.

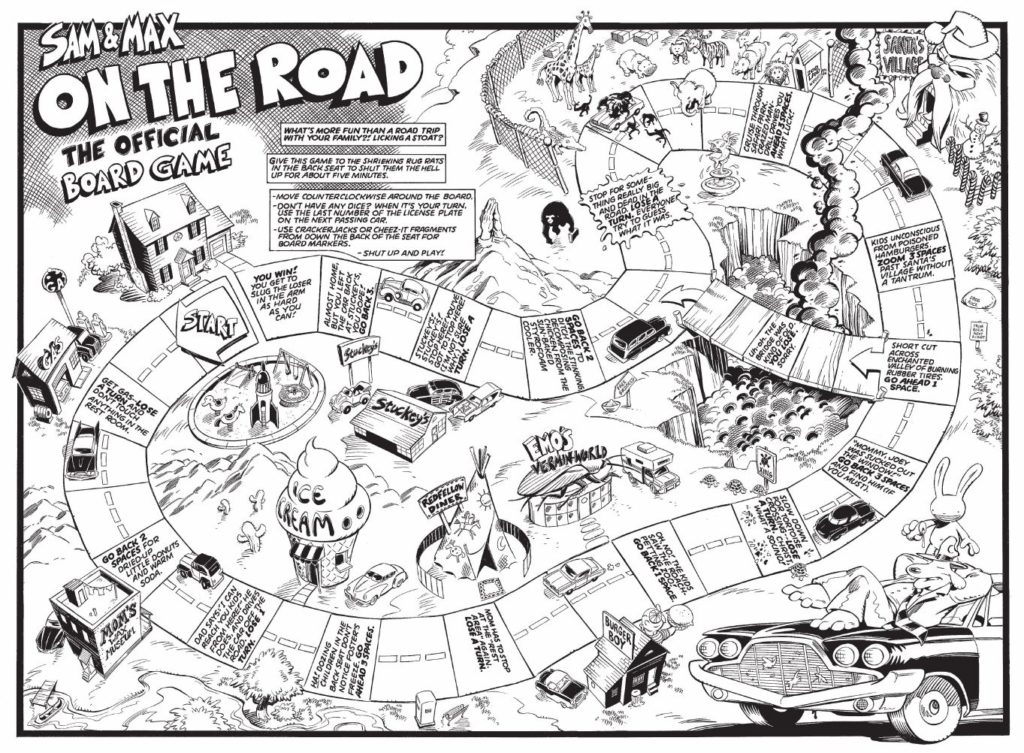

Said canon was marked not only by conventional comics storytelling — if anything involving the pair could ever be described as conventional — but also by a number of more interactive “activities” for the reader: Sam and Max paper dolls, puppets, etc., all sketchily described and sketchily implemented in cheap black-and-white newsprint. (The sketchiness of it all was, of course, part of the joke.) There was even a Sam & Max On the Road Official Board Game, a roll-and-move exercise in random happenstance: “Go back 2 spaces for dried-up donuts and soda”; “Kids unconscious from poisoned hamburgers. Zoom 3 spaces past Santa’s village without a tantrum”; “Get gas — lose a turn and don’t touch anything in the rest room.”

In the meanwhile, Steve Purcell the respectable above-ground commercial artist found himself working for none other than LucasArts. Shortly after the publication of the first Sam & Max comic, he was hired by them to illustrate what he intriguingly describes as “a role-playing game with cat-head babes.” When that project rather unsurprisingly got cancelled, he was laid off, but was soon brought back on again to draw the box art for the second SCUMM adventure game, Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders. That work won him a full-time job, upon which there followed much more in-game and box art for more adventures: Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Loom, the first two Monkey Island games.

Purcell didn’t come to LucasArts alone: a certain dog and rabbit accompanied him to his new job. The place was filled with bright young men, with young men’s taste for humor that might not always pass muster with the censors in the executive suites. (For proof, one need only look to the acronyms associated with key components of the SCUMM engine, which were tortured into conformance with various forms of bodily fluid: SPIT, FLEM, BYLE, MMUCUS.) Sam and Max fit right into this milieu. Indeed, the pair began to infiltrate LucasArts’s computers almost immediately, as, bowing to his colleagues’ demands, Purcell conjured up some graphics of them for everyone to play around with. Already by the time a couple of new hires named Dave Grossman and Tim Schafer were enrolled in the so-called “SCUMM University” in late 1989, Purcell’s creations had become fixtures of office life. Schafer:

Every afternoon Ron [Gilbert] would come up and tell us how to do one thing, like, “Here’s how you add a room to the game” or “Here’s how you add a character.” We had this Sam & Max art that Steve Purcell had made just for SCUMM U, which was Sam and Max’s office, which I don’t think ever saw the light of day. It had a few animation states — a staticy television set, rabbit ears made out of a coat hanger that could be in two different positions, and we’d go, “I’m gonna make the static on the TV animate,” and then we’d spend all day doing that, and by the end of it we were pooling in art assets from Indiana Jones, and all the Scummlets started making their own crazy, weird, improvisational SCUMM games set partially in the Sam & Max universe. I had a remote-control car in mine that would drive through a mouse hole in their office and then would come out of a filing cabinet in Nazi Germany…

Except for Nazi Germany, most of these things — including the office, the television with a coat-hanger antenna, and even the mouse hole — would later appear in the official Sam & Max game, albeit with dramatically upgraded graphics.

But even well before that came to be, Sam and Max were already getting a form of official recognition from LucasArts, one that the people in the executive suites probably weren’t really aware of. The first two Monkey Island games, the first two Indiana Jones games, and Day of the Tentacle all found somewhere to shoehorn in a mention of the LucasArts staff’s favorite comics characters. When in 1990 LucasArts instituted a newsletter for their fans in the tradition of Infocom’s old New Zork Times, they asked Purcell to provide a Sam & Max comic strip for each issue.

Still, there’s a considerable distance between such sly insertions as these and a full-fledged Sam & Max computer game. The latter may well owe its existence to expediency as much as anything else. In 1992, LucasArts’s management wanted a second adventure to join Day of the Tentacle on their release docket for 1993, but had yet to approve a project plan for same. As time ran short, Sam and Max had virtually the entire creative staff pulling for them, along with a wealth of rough art and design ideas that had been kicked around through the likes of SCUMM University for years by that point. So, Sam and Max got to make an unlikely transition from indie comics characters to the stars of a very mainstream, very mass-market computer game from The House That Star Wars Built.

Ironically, the Sam & Max game got the green light just as Purcell himself was pulling back a bit from LucasArts. After some three years of full-time employment there, he’d just elected to return to freelancing, sometimes for LucasArts but sometimes for others. Thus the official designers for the game became a heretofore unheralded pair named Sean Clark and Mike Stemmle, who had worked as programmers on earlier SCUMM games. One can all too easily imagine such an arrangement going horribly wrong, missing the unique tone of the comics entirely. But thankfully, Clark and Stemmle proved to have a gift of their own for that trademark Sam & Max form of comedic mayhem, while Purcell himself and his soon-to-be wife Collette Michaud — another LucasArts artist, whom he had met on the job — made time to write or at least to edit most of the dialog.

Another obvious risk to the project was that of bowdlerization by nervous managers and marketers. Here again, though, it got lucky. Purcell:

I think the game is really close to the spirit of the comics. There’s violence, mild cursing, and a commendable lack of respect for authority, not to mention circus freaks and yetis. There’s less gunplay in the game simply because a gun is a terrible object to give someone to use in an adventure game unless you carefully guide the player to use it in a more interesting way. I don’t remember anything getting cut by management. Much to their credit, I think they trusted our judgment.

The theme of the game whose full title became Sam & Max Hit the Road was drawn from that old joke of a board game, as well as from kitschy roadside America more generally. By 1993, the cozy tradition of the cross-country family road trip — Route 66 and all that jazz — was starting to feel a little shabby in a post-oil embargo, post-interstate highway, postmodern America. Sam & Max steers into that shabbiness with a gonzo sensibility that’s more Hunter S. Thompson than Jack Kerouac; none of that romance-of-the-open-road nonsense for this duo! Instead they take us to pathetic would-be tourist traps like “The World’s Largest Ball of Twine!”, “Gator Golf,” “The Mystery Vortex,” “The Celebrity Vegetable Museum,” and “Frog Rock” (which doesn’t look much like a frog at all). The game tempers any sepia-toned nostalgia it might be tempted to evoke with an awareness that, really, all of this stuff was pretty tacky and stupid even in its heyday. And I haven’t even mentioned the spot-on parody of Graceland — presented here as Bumpusville, home of Conroy Bumpus, singer of the country classic “Let’s Get Drunk and Shoot Things.”

Snuckey’s convenience store, a monument to a homogeneous junk-food culture that stretches from sea to shining sea; there are several Snuckey’s in the game, and they all look exactly the same. “Max, crack open the Tang and those little cereal boxes with the perforated backs. I love that crap!”

And the reason for all this cross-country travel? Well, Sam and Max themselves never seem all that interested in the central mystery of the game, so why should we be? For the record, though, it’s something about a Sasquatch or yeti or something who’s escaped — or been kidnapped — from a carnival show. Jump through enough hoops and you’ll be rewarded with a bizarre denouement involving, as Sam puts it, “the wholesale destruction of the modern symbols of civilization in the western United States. You bet we’re proud!”

Suffice to say that you don’t play this game for the plot; you play it for the humor. A quarter century on from its creation, the latter has lost none of its sharpness. Sam & Max Hits the Road remains a veritable master class in comedy writing, with a sense of effortlessness about it that many another adventure game, huffing and puffing all too visibly in its own desperate efforts to be funny, could stand to learn from. Writing this game wasn’t truly effortless, of course, but rather involved countless hours of careful honing; as any of the great comedians working in any medium will tell you, being funny is first and foremost hard work. Yet the end result ought to feel spontaneous and easy, as it does here. The verbal jokes and visual gags are never belabored, never beat into the ground. On the contrary: they come so thick and fast that they can sometimes be a bit difficult to catch and appreciate. This is one of the few games I can think of that benefit from replaying just in order to savor all of the layers of its writing and presentation.

A Brief, Unsatisfying Interview with Sam and Max

Could you introduce yourselves?

Sam: I’m Sam. He’s Max. He’s a bunny. I’m a dog. We’re dangerous, but we work cheap.

How did you two form the Freelance Police?

Max: It was easy once we filed the monolithic heap o’ documents with the local government. They didn’t even notice that in the paperwork I claimed to be a nine-foot hamster and referred to myself as The Scatman.

Sam: Did you know that anybody can walk into a store and buy a real police badge? It really comes in handy when you want to enter the homes of people you don’t know.

What’s the toughest case you’ve ever cracked?

Sam: I guess the toughest case we cracked was when I lost the car keys and went as far as to have Max’s stomach pumped before I realized they fell down behind the radiator.

What special skills do each of you bring to the job?

Sam: Well, I have the ability to drive a car, enjoy a home-cooked meal, and get lost in a good book simultaneously.

Max: I can open a can of tuna fish with my own face.

In the best spirit of postmodern comedy, Sam and Max unleash a constant stream of blatant or subtle meta-textual commentary. When other games try to do this sort of thing, they tend to overplay their hand, with the result coming off as nervous tics on the part of creators who lack confidence in the integrity of their own fictions. Sam & Max Hit the Road, however, knows its fiction has no integrity, and revels in it. Likewise, it knows that we know how the highly artificial guide rails of genre-based storytelling run, and acknowledges that shared understanding. The selection of media tropes the game riffs off of is deep and broad, placing high and low culture on an equal footing, as any good postmodernist should. (“Every time I catch enough fish to fill a net, the helicopter swoops down and carries the fish to the Ball of Twine diner,” says one poor Sisyphus of a fisherman. “It’s like being stuck in a Norman Mailer novel.”)

But the greatest comedy goldmine here is always Max, who’s fun to watch even when he’s not really doing anything. He prowls restlessly about every area you visit, a perpetual live wire who looks likely to do something highly inappropriate and profoundly dangerous at every moment. LucasArts took an interesting approach to controlling the two protagonists. Rather than being able to switch direct control between Sam and Max, as in their previous multi-protagonist games Maniac Mansion and Day of the Tentacle, you ostensibly control Sam alone, but can “use” Max upon things in the world like you might an inventory object. It’s a brilliant choice. Max’s greatest comedic virtue is his sheer unpredictability, and this approach preserves that; even when you’re consciously “using” Max on something, you never know quite what he’s going to do.

Dialog works the same way; instead of presenting you with a cut-and-dried menu of questions or statements to make in conversations, the game lets you choose between the abstract options of a question, an exclamation, or the always worthwhile choice of the complete non sequitur. For “nothing would kill a joke worse than reading it before you hear it,” as Steve Purcell puts it.

In other ways as well, Sam and Max became a field for considerable experimentation with what had been the standard LucasArts adventure interface ever since Maniac Mansion: an interactive picture of your surroundings filling the top three-quarters or so of the screen, a menu of verbs filling the bottom of the screen. Sam and Max‘s design team eliminated the latter entirely for the first time since Loom; instead of clicking a verb on a menu here, you right-click to cycle the mouse cursor through them. Although welcome in the sense that it gave LucasArts’s talented artists more room to paint their scenes, the new approach can be just a little awkward to work with, requiring an awful lot of repetitive clicking even once you’ve managed to cement in your mind what each of the cursor icons actually means.

One can make vaguely similar complaints about other aspects of Sam & Max. Certainly in comparison to Day of the Tentacle, a game which LucasArts polished to a well-nigh unprecedented sheen, Sam & Max can come across as ever so slightly ramshackle. Its scenes are often designed to scroll as the protagonists move across them. This is fair enough in itself, but it’s sometimes difficult to identify what is and isn’t a hard edge, especially in certain scenes where you must click in just the right vertical spot on one edge or the other to progress further to the left or right. This was such a problem for me when I played the game recently that I wound up consulting a walkthrough on a few occasions when I thought I was completely stumped, only to find that I simply hadn’t fully explored a location due to this interface confusion. These sorts of issues — sometimes referred to as “fake difficulty” in that they’re fundamentally external to the world being explored — were admittedly par for the course in the games from LucasArts’s contemporaries. But LucasArts themselves had made their name by rising above them to a perhaps greater extent than they manage here.

A particularly hard-nosed critic might also find reason to complain about some of the individual puzzles. Although the game does stay scrupulously true to the letter of the LucasArts design philosophy of no deaths and no dead ends, quite a few of the puzzles here are so warped that they can really only be solved via the tried-and-true “use everything on everything else” approach. While this feels thoroughly true to the anarchic spirit of the game’s source material, it’s much more debatable in the context of good adventure design in the abstract.

But then again, the whole game is so lively, and so full of funny responses and hilarious Easter eggs, that it’s usually more entertaining than tedious to lawn-mower through its scenes in this way. And there is a smattering of really good set-piece puzzles to enjoy as well. The “Gator Golf” scene, in which Sam gets to play golf on an alligator-infested swamp of a course, is an example of a puzzle that’s both intellectually stimulating and absolutely hilarious, the sort of thing that could only have appeared in Sam & Max Hit the Road. To alleviate the tension when you aren’t sure how to proceed, there’s also a few superfluous action games, like the rather grisly take on Battleship that’s known here as Car Bomb and a concoction known as Highway Surfin’ which combines a speeding automobile, Max on the roof of said automobile, and a bunch of low-hanging road signs. If not exactly good in the way we conventionally define such things, the mini-games are, like just about everything else about Sam & Max Hit the Road, really, really funny.

But the game’s rougher edges perhaps aren’t all down to the gleefully low-rent nature of its source material. Once again, a comparison with Sam & Max‘s immediate predecessor on the LucasArts release docket can be instructive in this context. Superlative though Day of the Tentacle‘s execution was, that game was also at the end of the day a thoroughly safe choice for LucasArts — the sequel to a beloved game, built around a style of cartoon humor with which Middle America was long-acquainted. Sam & Max, on the other hand, was a more dangerous proposition in more than one sense of the word. Even as we laud LucasArts’s management for the real bravery it took to let their creative staff make and release it at all, we can also see signs that they weren’t willing to pour quite the same amount of time and money into such a relatively risky concept. Tellingly, they didn’t pull out all the stops to release a CD-ROM-based “talkie” version of Sam & Max at the same time as the floppy-disk-based version, as they had for Day of the Tentacle. Instead they decided to wait a bit, to make sure there was in fact a market out there worthy of the additional investment.

Some of the first reviews would actually seem to confirm any suspicions LucasArts’s management might have had that Sam & Max could be more of a niche taste than a crowd pleaser. Charles Ardai, writing for Computer Gaming World, found all of the “self-referential jokes, sneering remarks, deadpan derision, sarcasm, and ridicule” — even the “unnerving” jazz-influenced soundtrack — to be decidedly off-putting. “Sarcastic New York intellectuals like [some of] my friends will find its tone wholly agreeable,” he concluded, “but whether it plays in Peoria remains to be seen” — thereby echoing a question that was doubtless much on the mind of some at LucasArts.

But, happily for everyone concerned, Sam & Max didn’t prove the commercial disaster which some of the Nervous Nellies at LucasArts might have feared. Right from the beginning, significant numbers of gamers responded strongly to the same edgy humor that seemed to leave some reviewers a little nonplussed. And, make no mistake, some reviewers loved it as well. Certainly Rick Barba, writing for Electronic Entertainment, loved it unreservedly: “It’s hip, funny, adult, and well-written. It’s what literate adventure gamers have been craving for years.” Interestingly, the early British reviews were much more uniformly positive than the American ones, perhaps reflecting the longstanding British taste for a drier, less literal stripe of humor — or perhaps just reflecting the longstanding British fascination with the weirder aspects of Americana.

With the game’s sales and very positive reception in at least some quarters having sufficiently allayed any doubts at LucasArts, the CD-ROM version appeared about six months after the floppy-based version. It was well worth the wait. The same production team that had made Day of the Tentacle such a lesson to the rest of the industry in how to do a talkie right took charge of Sam & Max as well, with similarly stellar results. Sam and Max themselves were voiced by a pair of cartoon veterans named Bill Farmer and Nick Jameson respectively, both of whom were perfect for their roles. After hearing its stars for the first time, it becomes almost impossible to imagine playing Sam & Max without their voices. And this, of course, is just the reaction a talkie ought to provoke.

Since Sam & Max Hit the Road, the titular pair have continued their exploits in the pages of more comic books, in a brief-lived and sadly bowdlerized television series, and eventually in a string of episodic adventure games from Telltale Games, who positioned themselves as the post-millennial heirs apparent to the LucasArts adventure tradition. Yet I’m not sure whether they’ve ever again been quite as sharp and funny as they were here, in their very first computer game. I can certainly write that, despite the competition from all of these other iterations of what’s developed into a minor media franchise in its own right, the stature of the original Sam & Max computer game has only grown over the years. Today it continues to stand out from the field of its contemporaries as a harbinger of a gaming future that would admit more diverse voices to the dialog, drawing from a more sophisticated palette of non-ludic cultural influences. Most of all, however, it remains what it has always been: one of the funniest games ever made. What better reason could you need to play it?

(Sources: the omnibus comic Sam & Max Surfin’ the Highway by Steve Purcell; Computer Gaming World of April 1991, January 1992, August 1993, and February 1994; Retro Gamer 22, 28, 70, 110, and 116; CD-ROM Today of August/September 1994; Edge of February 1994; Electronic Entertainment of March 1994; Game Developer of March 2006; LucasArts’s newsletter The Adventurer of Fall 1990, Spring 1991, Fall 1991, Spring 1992, Fall 1992, Spring 1993, and Winter 1994. Also “The History of Sam & Max,” as presented on the old Telltale Games home page.

Sam & Max Hit the Road is available for purchase from GOG.com and other digital storefronts.)